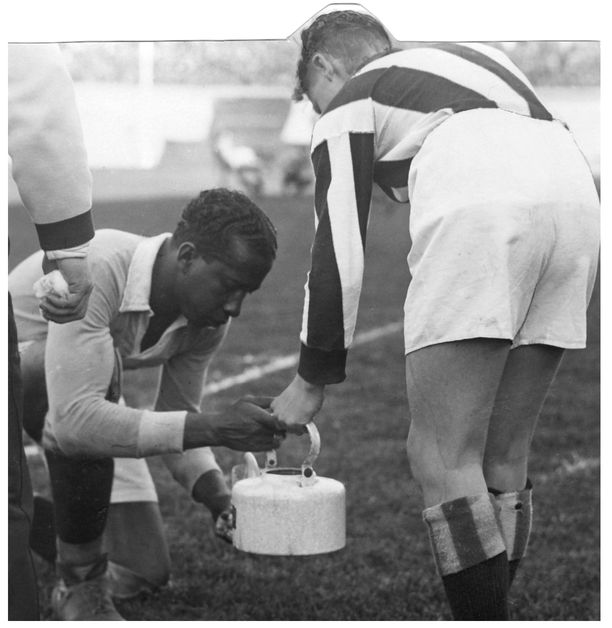

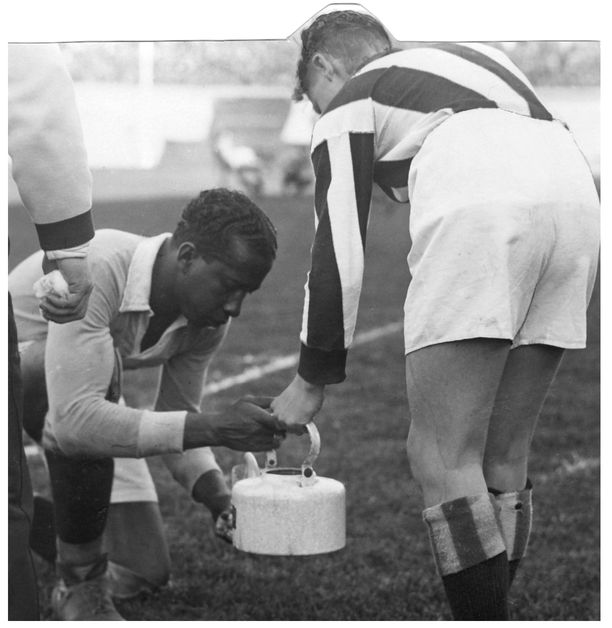

Uruguayan captain José Leandro Andrade

CHAPTER 10

The South American Connection

Both the shortcomings of Athletic, one of Spain’s most successful soccer clubs, when faced with foreign competition in the first decades of the twentieth century and the emergence, by contrast, of a new soccer power outside Spain were only too evident during a South American tour by a group of Basque players in the summer of 1921. The players, many of them Spanish internationals, including Belauste, the Olympic goal scorer who had become a national legend, set off by ship from Lisbon on June 27. The team arrived just over two weeks later and were received like heroes by a large and enthusiastic Spanish (mainly Basque) immigrant community in the port of Buenos Aires.

Their first match was against a selection of players from the Argentine capital. Most came from the working-class neighborhood of Barracas, where Alfredo Di Stéfano was born five years later. The visitors were overwhelmed by the superior style and skill of their hosts. The Argentines put on an extraordinary display of tiqui-taca soccer: control, possession, and quick, short movements of the ball.

In Argentina soccer had escaped from the manicured fields of the rich and discovered new roots in the slums, on barren earth and against makeshift walls. It delivered a new language that connected the local underclass with the poor immigrants who arrived from southern Europe, northern Spain, Italy, and the Middle East. As South American novelist Eduardo Galeano has written, “A homegrown way of playing soccer, like the homegrown way of dancing, came to be born. Dancers drew filigrees on a single floor tile, and soccer players created their own language in that tiny space where they chose to retain and possess the ball rather than kick it, as if their feet were hands braiding the leather. . . . On the feet of the first Creole virtuosos el toque, the touch, was born: the ball was strummed as if it were a guitar, a source of music.”

The Basque team lost 0–4. They recovered some of their honor in the following games played in the cities of Rosario in Argentina, Montevideo in Uruguay, and São Paolo in Brazil, but this did not turn into the triumphant tour that they had expected. The final tally was two victories, one draw, and five defeats.

Whereas Spanish club soccer had mixed fortunes when it faced the emerging power of South America, Spain’s national squad simply found itself humiliated. The squad returned from the 1924 Olympics, effectively a world championship, empty-handed, with Uruguay taking the gold. It was Uruguay that was set to place South America firmly on the map of world soccer when its team swept down on the Paris Olympics and crushed all opponents.

Other South American countries, Germany, and the United Kingdom were absent from the Olympics, yet soccer confirmed itself as one of the world’s most popular sports, with thousands of spectators watching twenty-five matches over a two-week period. Uruguay beat Switzerland 3–0 after demolishing Yugoslavia, the United States, France, and Holland. French writer Gabriel Hanot reported on the arrival of an exciting new soccer-playing nation: “The principal quality of the victors was a marvelous virtuosity in receiving the ball, controlling it and using it. They have such a complete technique that they also have the necessary leisure to note the position of partners and team mates. They do not stand still waiting for a pass. They are on the move, away from markers, to make it easy for team mates.” Hanot went on to compare the Uruguayans with the early English pioneers who had such an early influence on Spanish soccer: “The English are excellent at geometry and remarkable surveyors. . . . They play a tight game with vigor and some inflexibility.” By contrast, the Uruguayans “are supple disciples of the spirit of fitness rather than geometry. They have pushed towards perfection the art of the feint and swerve and the dodge, but they know also how to play directly and quickly. They are not all ball jugglers. . . . They create a beautiful soccer, elegant but at the same time varied, rapid, powerful and effective.” Hanot’s conclusion left little room to doubt that a revolution on no small a scale was sweeping through international soccer. “These fine athletes are to the English professionals like Arab thoroughbreds next to farm horses.”

In a press conference attended mainly by French journalists, the Uruguayan captain José Leandro Andrade, said that his players had trained by chasing chickens on the ground. The early influence of Latin Americans on Spanish soccer had a magical quality to it, verging on the fantastical. The skills involved were real enough, however, and foreshadowed some of the great figures of Spanish club soccer, from Di Stéfano to Maradona and Ronaldo and later Lionel Messi.

Andrade himself was an emblematic figure with the La Celeste Olimpica, as the Uruguayan team came to be known. He was also the first black player to earn respect at the international level, despite his off-field extravagances. When the Paris tournament was over Andrade stayed on for a while in the French capital, enjoying a bohemian lifestyle and becoming a popular figure of the nightlife cabaret scene—dressed in a top hat, striped jacket, silk scarf, and bright-yellow gloves and carrying a cane with a silver handle.

Four years later he won his second Olympic gold medal, when Uruguay faced a strong challenge from Argentina in the final, and in 1930 again he was instrumental in the Uruguayan team’s success, this time conquering the first-ever World Cup to be organized by FIFA. Thirteen countries took part in the tournament hosted by the two-time Olympic champions, only four of them from Europe—Belgium, Romania, Yugoslavia, and France. In common with other countries that absented themselves, Spain argued that taking its team across the Atlantic in the midst of a growing recession was something the country could not afford, a poor excuse given that Uruguay agreed to cover all the costs, including travel.

In reality Spain was struggling to come to terms with the humiliating fact that its former Latin American colonies were producing as good if not better soccer—the old colonial master was in danger of reverting to pupil status. The Black Marvel, Andrade, was not the only player to dazzle fans with his exquisite plays. Another of the cast of South American legends was Ramón Unzaga, the inventor of the bicycle kick, or chilena, in tribute to his nationality, which was first used on Spanish soil by a fellow national, David Arellano, during a tour of the country by his team, the Chilean team Colo-Colo, in 1927.

By then the growing superiority of Latin American players showed in their ability to bring down to earth some of the great myths of Spanish club and international soccer history. For example, in a home game played between Uruguay’s Peñarol and Español of Barcelona, the thirty-six-year-old veteran Uruguayan striker José Piendibene managed to completely outfox the great goalkeeper Zamora with a typical display of masterful ball control. Galeano takes us through the moves:

The play came from behind. Anselmo slipped around two adversaries, sent the ball across to Suffiati and then took off expecting a pass back. But Piendibene asked for it. He caught the pass, eluded Urquizu and closed in on the goal. Zamora saw that Piendibene was shooting for the right corner and he leapt to block it. The ball hadn’t moved. She was asleep on his foot: Piendibene tossed her softly to the left side of the empty net. Zamora managed to jump back, a cat’s leap, and grazed the ball with his fingertips when it was already too late.

People still talk about that goal in Uruguay, although the suggestion that Piendibene was given a new house as a prize for beating the greatest soccer player in the world proved false. He was given a gold medal instead. After the Basque squad and Español, other teams like Barca and Real Madrid toured the Southern Cone. The experience for a while raised the standard of play in the nascent Spanish league, formed in 1926. However, the promise of Spanish soccer as epitomized by Spain’s victory over England three years later foundered amid the growing political instability in the run-up to the country’s civil war.