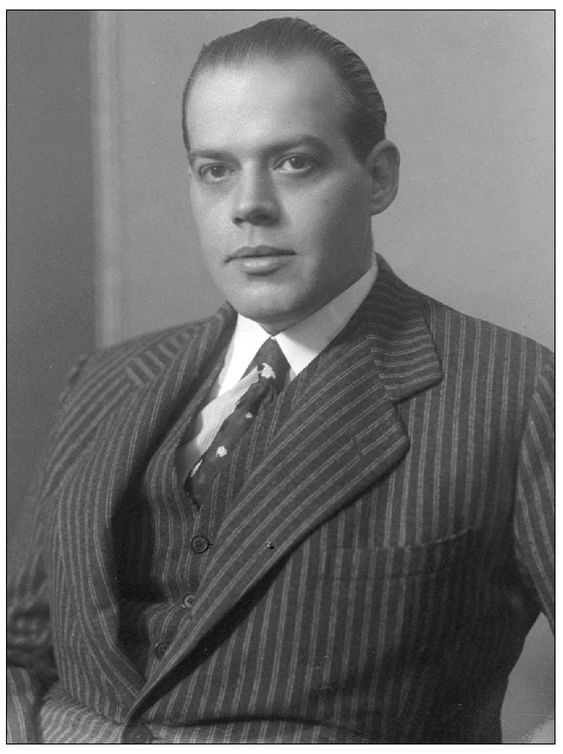

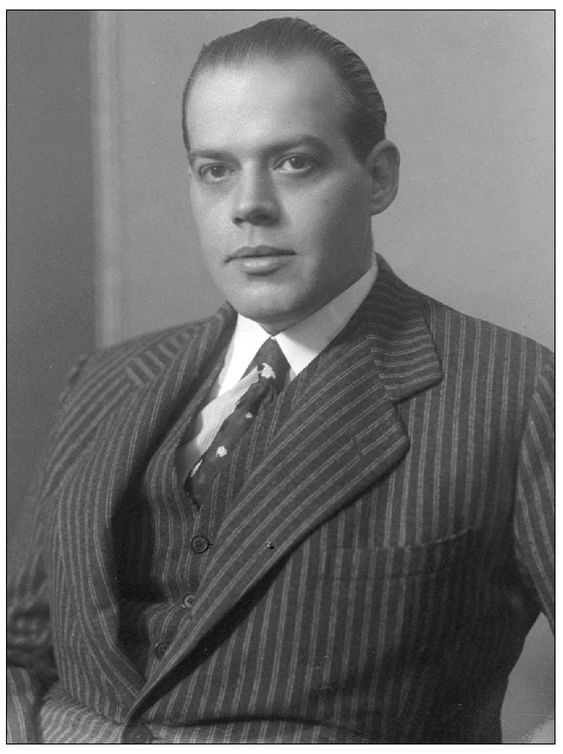

FC Barcelona President: Josep Sunyol

CHAPTER 11

Gathering Storms

When in the early 1920’s the dust had temporarily settled on the cataclysms of war, revolution, hyper-inflation and austerity, there was in all these societies a profound need and desire for hedonism and escape, for pleasure and for play, from the fabulously rich to the appalling poor. Soccer was one of these pleasures.

—DAVID GOLDBLATT, The Ball Is Round

Spain was not immune to the transformation of the political and social landscape that impacted most of Europe as a result of the First World War. If the development of its soccer still lagged behind that of several other countries on both sides of the Atlantic, it was because its development as a country too seemed out of step, out on a limb, and seemingly permanently in crisis.

Between 1921 and 1922, the emerging giants of Spanish club soccer, FC Barcelona and Real Madrid, each inaugurated a new stadium. Of the two, FC Barcelona’s Les Corts, built a few blocks away from Barca’s current stadium, the Camp Nou, had the biggest capacity, with seating for twenty thousand and a covered stand for a further fifteen hundred. Real Madrid’s Chamartín stadium, constructed on the very site where the Santiago Bernabéu stadium stands today, had a capacity of only fifteen thousand.

Although there can be little doubt that attendance records generally for Spanish soccer matches had been increasing up to and during the First World War, the growth was still of a lower order of magnitude to, say, that of England during the early twentieth century or during this time of the emerging nation-states in central Europe. For example, in 1922 the crowds of that year for the most popular game—that between Austria and Hungary—had swollen in just four years from fifteen thousand to sixty-five thousand.

The following year the young Spanish prince Don Gonzalo marked the inauguration of Real Madrid’s stadium by kicking the ball of honor and in a boyish voice crying out, “Hala, Madrid” (Let’s go, Madrid). The phrase would be adopted as the club’s official rallying cry and echoed by generations of fans to this day. Just four months later, on September 13, 1923, Captain-General Miguel Primo de Rivera staged a bloodless military coup and shut down parliament, claiming that party politics had become corrupt and the monarchy ineffectual while making a token gesture to the aristocracy by leaving Alfonso XIII as a symbolic king without power.

Prompted into action in part by the politicians’ mishandling of a protracted Spanish colonial war in Morocco, Primo de Rivera was an emotional Spanish patriot of the old school, believing that Spaniards should be Catholic and united. He considered atheism, including all its manifestations such as Marxism, to be a mark of the devil. His greatest enemies were Spaniards who called themselves anything but Spaniards and toyed with the idea of becoming more separate from Madrid, by pursuing their own devolved government and speaking their own language.

Among Spain’s most powerful regions, it was Catalonia that posed the greatest threat in the eyes of the dictator, with its nationalist movement becoming increasing radicalized and lurching to the left. A clash between the new military government and Catalonia’s potent sporting symbol, FC Barcelona, seemed inevitable, and so it proved.

June 14, 1925, came to be a date remembered in the collective memory of Catalan nationalism and many Barca fans as a day of infamy. The occasion was a fund-raising game FC Barcelona had organized for the Orfeo Catala, a choral society set up to carry on the work of the father figure of Catalan music, Josep Anselm Clavé. At halftime the crowd whistled as a band of English marines from a visiting Royal Navy vessel played the first notes of the Spanish national anthem. When the marines abruptly stopped and then struck up again, playing the English national anthem, the crowd broke into spontaneous applause. The demonstration had been fueled by Primo de Rivera days earlier banning the public use of the Catalan language and closing down local government offices. Now the Madrid government moved in with a vengeance, with Barcelona’s newly appointed civil governor, Joaquín Milans del Bosch, fining the Barca directors and imposing a six-month ban on Barcelona’s activities as a club and as a team.

A majority of Spaniards were immensely relieved when the increasingly ineffectual Primo de Rivera resigned and left Spain in January 1930. But the dictatorship had also alienated popular support for a king who had passively acquiesced in the authoritarian regime. King Alfonso XIII was forced to abdicate and go into exile when Spain’s new Republican government was proclaimed by a group of liberal intellectuals.

Newsreel film of those heady days shows thousands of Spaniards taking to the streets of Madrid and Barcelona following the proclamation on April 14, 1931. Suddenly, after centuries of political instability fueled by dynastic struggles and military interventions, there seemed to be the possibility of a truly democratic Spain. It proved a pipe dream, as a succession of increasingly radicalized, short-lived left-wing and right-wing elected civilian governments struggled with the reality of Spain’s continuing economic and political underdevelopment: vast disparities between rich and poor, particularly in the countryside; unresolved tensions between centralists and the regions, as Catalan and the Basque nationalists pressed for increasing autonomy from Madrid; bitter quarrels among groups of democrats about how far left, anticlerical, and decentralized the new Republic should be; and all against the enduring presence of two traditionally powerful institutions—the military and the Catholic Church—that saw its privileges under threat.

In Barcelona politics and soccer turned into an increasingly volatile mix. In 1928, as the Primo de Rivera regime was entering its death throes, a young radical lawyer named Josep Sunyol became a member of FC Barcelona’s governing board and president of the Federation of Associated Catalan Football Clubs.

Sunyol used his newspaper, La Rambla—which split its coverage between sport and nonsport items—to appeal to a new social order where soccer and politics formed an essential part of a new democratic society. While the perspective of soccer through the prism of a reformist political agenda seemed to mirror the enlightened ideals of the early founders of Real Madrid, Sunyol’s politics was firmly rooted in Catalonia, with FC Barcelona as a role model. In an early manifesto, Sunyol explained what he meant by his slogan, “Sport and Citizenship.” He wrote, “To speak of sport is to speak of race, enthusiasm, and the optimistic struggle of youth. To speak of citizenship is to speak of the Catalan civilization, liberalism, democracy, and spiritual Endeavour.”

As a lawyer and a journalist, Sunyol tried to present himself as, first and foremost, a Catalan patriot rather than a party dogmatist and a true soccer fan. In July 1935 he was elected FC Barcelona’s president. In his acceptance speech he declared that he would endeavor not to let politics get in the way of his work for the club. But for all his love of sport, Sunyol was primarily a politician and regarded the soccer of FC Barcelona as a means to an end rather than an end in itself. Three years earlier, in the summer of 1931 after the proclamation of the Second Republic, he had been elected as a deputy to the new parliament in Madrid as a representative of Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, a new pro-independence party.

In October 1933, in reaction to the emergence of a conservative government in Madrid, Sunyol’s party was among those who backed the unilateral proclamation of a Catalan government—a “Catalan state within the federal republic of Spain.” The initiative was blocked by Madrid, only to be revived and enacted after a Popular Front coalition of socialists and communists was swept to power in February 1936 when Sunyol and other Catalan radical nationalists once again took center stage.

For all the political effervescence, this was not a period of sporting success for FC Barcelona, under Sunyol’s presidency, and the club failed to win either the new league championship or the Spanish Cup in the 1930s. By contrast, Real Madrid on May 6, 1934, ended a seventeen-year drought in the Spanish Cup championship, beating Valencia 2–1 in the final and ending Athletic Bilbao’s run of uninterrupted success in the tournament. The final against Valencia was played in Barcelona. When the Madrid team arrived back at the Spanish capital’s Atocha station, they were greeted with a rendering of the “Himno de Riego,” the new national anthem of the Republican government after the demise of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship and the abdication and exile of King Alfonso XIII. The club had dropped Royal from its title in deference to the political situation.

Two seasons later, on June 22, 1936, Madrid played FC Barcelona in their first-ever Spanish Cup final clash. The game was played in Valencia’s Mestalla stadium. Madrid was leading 2–1 when Zamora threw himself full-stretch toward the left-hand goalpost and blocked a last-ditch attempt at an equalizer by the Catalan striker Escola. Within minutes the game was over, and Zamora, El Divino, was raised on the shoulders of his joyous fans. The team received an even more ecstatic welcome when they returned by train to the Spanish capital, as Madrid fans once again converged on the Atocha station.

By then, however, no amount of celebration could hide the fact that Spain was on the verge of disintegration, the incompatible politics of the Left and Right lurching out of control toward civil war in a context of increasing violence. A day after the Madrid-Barcelona match, General Francisco Franco, then the captain-general of the Canary Islands, wrote to the Spanish prime minister, Casares Quiroga, warning of growing military unrest. Franco had yet fully to throw his hat into the ring with the plotters of military officers and right-wing civilians, but it was just a matter of time before he did. The conspirators, concerned about the violent anticlericalism and the growing militancy of industrial and agricultural workers, and what they saw as the breakdown of order, were plotting a coup to stop the country from lurching further toward socialism. On July 18 the military uprising began, and the country’s history of failure, division, and frustration gave birth to its ultimate despair, the Spanish Civil War.