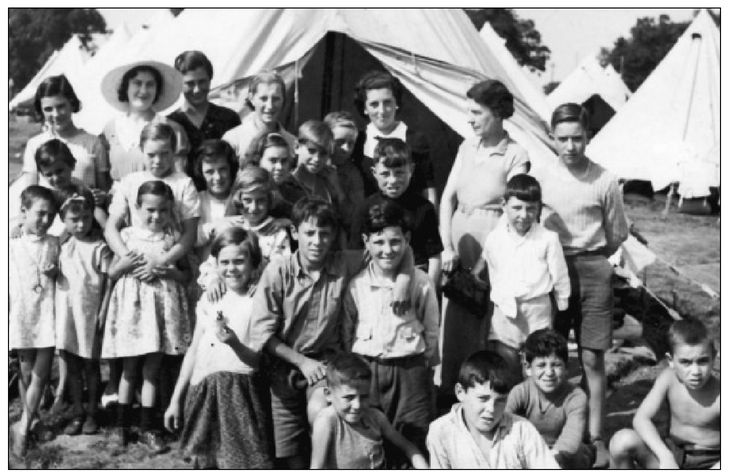

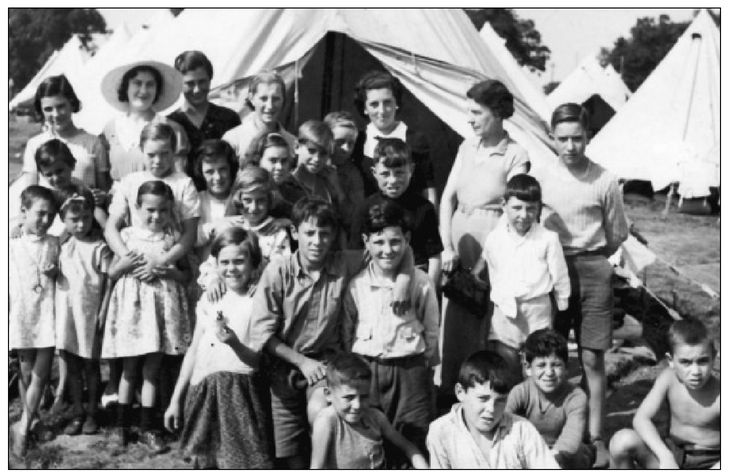

Basque refugee children, Southampton, England, 1937

CHAPTER 13

Soccer Against the Enemy: Part 2

On May 22, 1937, the Spanish Civil War had nearly another two years to run when nearly four thousand refugee children accompanied by teachers and priests arrived in the port of Southampton on board the SS Habana after crossing the Bay of Biscay from northern Spain. The ship had left a day earlier with its human cargo—the biggest single influx ever of child refugees into Britain—from Bilbao, as the Basque port faced conquest and occupation by the besieging forces loyal to General Francisco Franco. The children had been evacuated to escape the horrors of the conflict. Amid much political controversy back at home, Britain had waived its policy of nonintervention and agreed to escort Basque refugee ships to safe haven.

Conditions aboard the SS Habana were cramped and depressing, exacerbating the children’s feelings of distress from being separated from their families and sent off to a foreign land and an uncertain future. As the ship tossed and turned in the rough seas, children cried in the night, calling out for their mothers and fathers. Among them were fourteen-year-old Raimundo Lezama and his brother Luis from Bilbao’s industrial suburb of Barakaldo, the sons of a ship worker who had been detained in the Republican-held port of Sagunto and would spend much of the Civil War in prison.

While Mrs. Lezama was left caring for her only remaining child, a young baby girl, the two boys were thrown into an extraordinary new environment on arrival on English soil. Waiting for them were hundreds of volunteers and government officials with a relief operation that in its generosity exemplified the deep popular emotions stirred in Britain by the Spanish Civil War. Tumultuous scenes greeted the Habana as it berthed in the Southampton dock. The next day, the local newspaper the Echo headlined with the words “Basque Children Cheerfully Taking to Camp Life” and commented on “the excitement of feeding the multitude” in the temporary relief camps set up nearby. Hundreds of sympathizers converged on the town from around the UK, bearing gifts and food. A Salvation Army band played and a BBC crew filmed, all amid bunting left over from the coronation of King George VI that had taken place less than a fortnight before and had been deliberately left hanging to give the occasion a festive air. Later one of the children would recall, “When we entered the bay of Southampton, we thought we had entered a wonderland. Every little house lining the bay had its own pretty garden, well-tended, and all decorated to celebrate the coronation. Everything was bunting, flags, music playing, and people waving their handkerchiefs at us.”

It was not quite so idyllic as it appeared, however. Fearful that the children might be bearers of typhoid or some other potentially deadly infectious disease from the war zone, the Home Office insisted that each child be meticulously examined by health officers and disinfected in public baths. The camp where the children were initially taken and housed in tents soon turned into a muddy quagmire after two violent thunderstorms. Inexperienced volunteer aid workers struggled to communicate with children who spoke only Spanish and in some cases Basque. Yet the adults tried to keep the young amused with excursions, film shows, and a representation of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. But Southampton’s North Stoneham facility was only ever envisaged as a transit camp, and by September 1937, the Lezama brothers along with the other children had been dispersed to private homes and government-run residences.

Raimundo Lezama, separated from his brother, stayed in Southampton. He was given shelter, food, and rudimentary English lessons in a hostel run by nuns called Nazareth House, about a half mile away from the Dell, the stadium of Southampton FC. Raimundo was fed well by the nuns and subjected to a relatively benign regime that included music and outdoor activities, mainly soccer. While still a teenager he was scouted by Southampton FC, progressing from the schoolboy to the club’s “B” team and making his first-team debut as a goalkeeper on June 1, 1940, ten months after the outbreak of World War II. A few months later, and after a brief period working as a driver for the Royal Air Force, Raimundo was reunited with his brother, and both returned to Spain, where Franco had emerged victorious in the Civil War a year earlier.

In March 1937, about the time the Lezama brothers boarded the Habana , local politicians redefined Athletic Bilbao as the matrix of a national team representing the Basque Country called El Euskadi. The cause of the new national team had as one of its most fervent supporters and organizers José Antonio Aguirre, the first lehendakari, or president, of Euskadi (the Basque lands of Spain not including Navarre) during the Spanish Civil War. Aguirre in his youth had himself played for Athletic. Although he never made his mark as a player, Aguirre had developed a politician’s instinct. He had a keen sense of the club’s popular cultural roots and of the growing propaganda value of soccer as it developed into an international mass sport.

Aguirre’s Basque government was formed at a time when most of the region it claimed to represent was already occupied by the military rebel troops, except for the region of Vizcaya with Bilbao at its heart. After setting about creating a Basque army to fight for the Republic’s survival, Aguirre hit on the idea of having a soccer squad from the region go on a foreign tour to raise funds and international support for his cause. At the end of March 1937, with the Civil War reaching new levels of brutality on both sides, and at a time when the national soccer league was no longer functioning, a group of players responded to Aguirre’s call to arms by presenting themselves for training and selection at Bilbao’s San Mames stadium. There were some key reinforcements. Among them two Basque-born leading Spanish internationals, the brothers Luis and Pedro Regueiro, who had spent the years leading up to the Spanish Civil War playing for FC Madrid, and Isidro Langara from Real Oviedo in Asturias. While playing at the Asturian club, Langara became a three-time winner of the Pichichi trophy, awarded to the top scorer in the Spanish league. The striker became the figurehead of the celebrated delanteros electricos (electrical forwards) whose youthful talent and speed with the ball steamrolled opponents.

Among the other Basque players who traveled from other regions of Spain for the historic gathering in San Mames were Enrique Larrinaga from Racing Santander and two of the best Spanish defenders of the 1930s. One was Pedro Areso, an FC Barcelona player formerly of Betis whose ability to disrupt even the best-laid attack from the opposing side earned him the nickname El Stop. The other was Serafin Aedo, who played alongside Areso at Betis during the 1934–1935 season when the Sevillian team won the Spanish Liga for the first and only time in its history. Aedo was hoping to follow his friend Areso and pursue his professional career at FC Barcelona when the outbreak of the Civil War frustrated his plans after playing only one friendly with the Catalan club.

As part of the Basque Diaspora, the bulk of the volunteers were Athletic players who had played on the Spanish national squad during the Republic: Gorostiza, Blasco, Iraragorri, Cilaurren, Muguerza, Echevarria, Zubieta, Aguirrezabala. The players had also been involved in the trophy hunting of one of the strongest and most successful clubs in prewar Spanish soccer. This was the Athletic team that between 1930 and 1935 racked up the extraordinary record of two Pichichis (twice won by Gorostiza), a Zamora Prize for the best goalie (Blasco), the biggest thrashing in the history of the Spanish league (12–1 victory over FC Barcelona in 1931), two Copas del Rey, and four league championships. The squad was coached over a period of nearly a month at San Mames—and prior to the start of the extended siege of Bilbao—by a veteran Athletic center-forward of the early 1920s, Manuel Lopez Llamosos, nicknamed Travieso (Artful Dodger) for his mischievous wit, cunning, and restless unpredictability. Travieso took good care of the players, including supervising the tailoring of the team colors. However, for reasons that remain a mystery, he decided not to join them the day they set off on their foreign tour with a squad of eighteen.

His place as coach was taken by Pedro Vallana, a former Spanish international who had played for the Arenas Club de Guencho before becoming a referee. He was accompanied by Athletic’s massage therapist, Periko Birichinaga; a sympathetic local journalist, Melchor Alegria; and two officials, Ricardo Irazabal, vice president of the Spanish Soccer Federation under the Republic, and former Athletic president Manuel de la Sota, a member of one of Bilbao’s richest industrial family dynasties.

The squad was captained by Luis Regueiro. Such was the propaganda value of the former (Real) Madrid player and Spanish international that pro-Franco military rebels spun a story that he had disappeared after being executed by forces loyal to the Republican government. Regueiro’s sympathies were clearly with the Basque cause. He recalled many years later, “With Franco’s revolt under way it was no longer possible to play soccer [in Spain]. There was however a huge need to bring home to the rest of the world that we Basques were different to what some wanted to make us out to be. It was this idea that inspired us both in and outside the stadiums we played in abroad, winning games on the pitches, and generating sympathy and friends beyond them.”

Not every player was equally enthusiastic about the tour. Some hoped that, like the Civil War, it would prove short-lived. Both turned out to be protracted, fueling divisions that were exacerbated as the Spanish Civil War turned in Franco’s favor. One of the players, Zubieta, recalled years later: “We became nomads with our soccer as our only arm. . . . We had embarked on a new life, without knowing where we were heading, and I think that when we crossed the frontier into France, our hope was that we would return soon.”

The squad arrived in Paris in the spring and, after being greeted by local representatives of the Basque government, laid a wreath wrapped in the Basque national colors at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. In their first game, against the French Racing Club, on April 24, 1937, in the Parc des Princes stadium they won 3–0, with Langara scoring a hat trick. Celebrations over the victory proved short-lived, however, as news came in over French radio of the bombing by the pro-Franco Luftwaffe of the Basque town Guernica. While the bombing and the ensuing mass fatalities among the civilian population became an important propaganda tool for the Republican government, it raised concerns among the players for the safety of the families they had left behind, while also making them think more deeply about where their true political loyalties lay, as Franco moved to extend his control across the Basque Country.

From Paris the tour continued through Czechoslovakia and Poland before reaching Russia, where the squad stayed for two and a half months. Authorized accounts of the tour were written later by individual players, most of which were published during the censorship of the Franco years, when the cause of Basque nationalism became mythified by exiles. They focus on the soccer success of El Euskadi, with a majority of games won against national as well as local club teams and the occasional defeats blamed on a lack of that “fair play” that the Basques had learned from the English. Thus, of the 4–2 defeat against a Czech team in Prague, Langara recalled, “It was an outright robbery. They beat us on penalties. The referee, who seemed to be nervous because of an accident he had suffered just before the game, whistled penalties against us to calm his nerves. And whenever our goalkeeper Blasco blocked the ball, he insisted that the penalty had to be taken again, claiming unjustly that Blasco had moved.”

In Moscow the squad was not short of photo opportunities. They were filmed visiting a school and residence where Basque children who had been evacuated were being cared for. But the propaganda seemed to serve Stalin’s Russia rather than the cause of the Basque Country. Another player, Zubieta, recalled: “Playing soccer, drinking vodka, and staying in the hotel was how we spent our time in that far away and strange land and we had no contact with anything other than the world of sport.” The games played in Moscow drew large crowds of loyal Communist Party officials and members in a display of international solidarity as news reached the squad that the city of Bilbao had fallen to Franco’s troops. In Moscow the Basque soccer team’s local minders appear to have ensured that the visitors be screened from local political realities, not least the terrible political repression that was then reaching a particularly brutal point in Stalin’s Russia. The year 1937 may still be remembered by Basque nationalists as the year of the heroic expedition abroad of El Euskadi—a noble high point in the history of Spanish soccer—but this was also the most tragic and fateful year in the history of the Soviet Union. It was also the year when Stalin extended his “terror,” with the aim of physically annihilating the substantial socialist opposition to his bureaucratic and repressive rule.

Nevertheless, such awkward coincidences were ignored when memoirs of the tour were published after Franco’s death. Thus, the journalist who accompanied the players, Melchor Alegria, recalled in 1987, “Moscow was a huge success. All the games were played in a magnificent atmosphere, which was also very moving as it showed the understanding that the Russian people had for the suffering of the Basque nation. What proved particularly gratifying was when we were in Leningrad and were asked to stay in Russia at the request of the trade unions and other organizations.”

Such a rose-tinted view of the tour was not shared by everyone in the soccer community. The growing influence within soccer’s nascent international body, FIFA, of officials sympathetic to the Franco cause meant that some national soccer federations like Argentina’s tried to make life complicated for the Basque squad, canceling some planned games. When El Euskadi eventually returned to Paris, some of the players were secretly contacted by Francoist emissaries who told them that they were embarked on a lost cause and urged them to defect.

Only a very small minority of the squad broke ranks, but they were of sufficient standing to prove helpful propaganda tools for Franco during the final two years of the Civil War. The first to quit and sign up to the Franco cause was Athletic’s legendary Gorostiza, whose lightning speed as a left-wing forward earned him the nickname Bala Roja, or Red Bullet. He was followed by another Athletic star player and international, the midfielder Echevarria, and by the massage therapist, Birichinaga. Days later, on a windy autumnal day in October 1937, what remained of the squad boarded a transatlantic French liner, Ile de France, in Le Havre and sailed via Cuba to Mexico, where during the 1938–1939 season El Euskadi was allowed to compete in the local national competition, ending as runners up in the league table.

Soon afterward, when the Civil War ended in Spain with Franco’s victory, El Euskadi was disbanded, with each player receiving a payment of ten thousand pesetas. A year earlier their coach, Vallana, had left the tour in controversial circumstances. Before departing, he secretly negotiated a payoff equivalent to a two-month salary when his players had not yet been paid a cent. The incident did nothing to enhance a reputation damaged years earlier when in the 1924 Paris Olympics Vallana scored a disastrous own goal in a game against Italy that ended with Spain’s early exit from the competition. Rather than return to Franco’s Spain, Vallana chose to live in exile in Uruguay, where he worked as a sports journalist after retiring from soccer.

The majority of the team chose to spend the rest of their playing years in other countries in Latin America, thus contributing unwittingly to the soccer cross-fertilization between Spain and its former colonies that continues to this day. In Argentina, Zubieta, Langara, Iraragorri, and Emilin signed with San Lorenzo de Almagro, while Blasco, Cilaurrane, Areso, and Aedo joined River Plate. Others were signed up by the Mexican clubs Asturias and—ironies of ironies—España. Luis Regueiro and Aguirrezabala retired but settled, respectively, in Mexico and Buenos Aires. Although some of these players, such as Iraragorri, returned quietly to Spain after the Franco regime had long been established, the myth of the defiant squad with a strong sense of its separate cultural and political identity endured. As Manuel de la Sota, one of the financial backers of El Euskadi wrote in a prologue to a book on the team published after Franco died: “Bad luck had united us, but that luck turned out to be one of the most fortunate in my life. For thanks to it I came to know examples of our race who as well as being artists of a sport which they taught foreigners to play, were also standard bearers of the dignity of a small people whose name was Euzkadi.”

Months before Luis Regueiro played his first games abroad with the Basque national team, another former (Real) FC Madrid player, Santiago Bernabéu, whose name would in time grace one of the great stadia of world soccer, had enlisted in the Franco forces. Whereas Regueiro’s Republican sympathies had left him unharmed after the initial military uprising was frustrated in the Spanish capital, Bernabéu’s right-wing leanings had put him immediately at risk. Bernabéu was saved from a Republican firing squad thanks to the intercession on his behalf of another Madrid FC supporter and friend, the socialist Spanish ambassador in Paris, Álvaro de Albornoz. Thanks to the diplomat, Bernabéu was granted asylum by the French embassy in Madrid before being smuggled across the Pyrenees. He returned a few months later, in 1937, crossing into Spain from France at Irún and enlisting right away with the Franco forces that had taken the Basque town.

Bernabéu’s arrival in Irún, in the midst of the Civil War, was like a chronicle foretold, for it was here during the early 1920s when while playing as a young Madrid player that Bernabéu had famously suggested to his teammates in a game against Real Club Unión de Irún that they should celebrate each goal they scored with the cry “Viva España,” a phrase that the Franco forces later adopted as one of their rallying cries. With the passage of time it was reinvented as a popular chant by Real Madrid fans and came to have wider use whenever the Spanish national team played.

There is an old photograph of a still relatively young if already somewhat corpulent Bernabéu, as a corporal in the Franco army, dressed in military cloak and fatigues and smoking a pipe. He is strolling along the streets of the Basque seaside resort of San Sebastián, looking somewhat content with life. And he was. The original photograph was taken after Bernabéu had earned his first military medal for contributing to the rout of the pro-Republican units in the Pyrenean town of Bielsa on June 6, 1938. A few months later, just before Christmas, the first “national” sports newspaper to be published under Franco’s rule hit the streets of San Sebastián and other towns “liberated” by the military rebels. It was called Marca (brand or mark) in deference to the neo-fascist worship of totemic symbols. The tabloid newspaper, published initially as a weekly and later as a daily, served two interrelated purposes: to act as the official organ of the Franco authorities on sports matters and to turn the mass following of soccer that had been developing since the 1920s from the Left to the Right of the political spectrum. While adopting from the outset a clearly identifiable propagandist tone, it came to mirror the profound changes in the organization and politics of Spanish soccer that deepened as the Civil War reached its end and paved the way for a dictatorship.

Marca’s first front page appeared heavily influenced by the racist obsessions of Nazi Germany, which from the outset of the Civil War had helped arm the military insurgents and provided further military assistance. It had a photograph of a blonde girl making the fascist salute in tribute to “all the Spanish sportsmen and women.” In fact, the Civil War had meant that individual soccer players were no longer respected by either side for their skills, but supported or condemned depending on what side of the political divide they were perceived to be on. This would do long-term damage to the evolution of Spanish soccer, although Bernabéu himself would reap a good harvest from Franco’s victory because of his enduring loyalty to the Generalissimo. During his billeting in San Sebastián, Bernabéu was profiled in Marca as an iconic figure. The article paid homage to him as a man who in the 1920s had given Real Madrid some “great days of glory” as a player before serving as a director and then resigning in order to devote himself to “The (anticommunist) Cause.” Marca dramatized Bernabéu’s departure from Madrid, describing his “escape from the ferocious persecution of the red hordes” and noting that while he had sought asylum “in an embassy” (no mention of the French or the Spanish socialist ambassador who had saved his neck), his deliverance into safe hands came only after a series of further dramatic twists in the story of his heroic bid for freedom. The alleged dramas included taking cover as a patient in a general hospital and hiding in a chicken run before escaping through a trapdoor.

The newspaper profile included some memorable quotes from Bernabéu. In one he defined what he saw as the essence of sport in the New Spain that would emerge with Franco victorious: “The spectacle of a few sweaty youths must disappear and give way to a youth that is healthy in body and spirit under the direction of specialist trainers.” The article concluded with a final fawning tribute to its subject, noting that it was not just the character of players that was destined to change in the New Spain, but also the fans of Real Madrid, many of whom had supported the Republican government. “If we can count among them [the fans] people like our interviewee, the club’s resurgence will be rapid,” the article’s author stated.

The writer was none other than El Divino himself, Ricardo Zamora, the onetime goalkeeper of FC Barcelona who had transferred to Real Madrid before making one of the most spectacular saves in the history of Spanish soccer. The fate of clubs, players, and fans was sealed as much by where organizations or individuals happened to be as by an ideological preference, with conflicting loyalties resolved by death or the threat of it. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Zamora was confronted by an anarchist militiaman, brandishing a knife and condemning him as a right-wing extremist for contributing occasionally to the conservative Catholic newspaper Ya. Zamora, so he related later, had little doubt that his assailant was bent on killing him. But to his surprise the militiaman suddenly dropped the knife and embraced him after identifying himself as a Madrid FC fan. During the ensuing dialogue over the relative merits of Spanish clubs and their star players, the militiaman praised Zamora for all the great saves he had made and for helping his club become champions.

The two men parted company, now the best of friends. Zamora remained suspected by others of being pro-Franco. He was arrested days later and imprisoned without trial in Madrid’s Modelo jail. While he was there, a military broadcast from the Andalusian capital of Seville, which had been occupied within hours by forces loyal to Franco, reported that the “nation’s goalkeeper” was among dozens of well-known personalities who had been executed by the “reds.” The rumor was initially taken seriously enough for masses to be organized in Zamora’s memory in towns that had fallen to the Catholic rebels. But it was pure invention, part of the propaganda war.

In the Modelo prison Zamora was periodically paraded by his captors in front of visiting officials as if he were a prize possession. To be called out from your cell in those days was to confront the real prospect that you were on your way to a firing squad. Zamora later recalled that his legs would physically tremble every time he was summoned. However, he was able to survive mentally and physically thanks to the occasional soccer games that jailers and their prisoners played with each other in the Modelo’s main yard. Zamora was eventually released after an international campaign was mounted on his behalf in France, and he took refuge in the Argentine embassy in Madrid, where arrangements were made to transport him, his wife, and young son out of Spain. By then Zamora had decided that his best interests lay in remaining unrecognized by the public, at least until he was safely across the Pyrenees. So one day, once his escape plan had been formed, he emerged from the embassy wearing dark glasses and having grown a beard. The disguise did not fool the militiaman who was on sentry duty. “Hey Zamora, hombre, what you doing with the beard?” The interrogator turned out to be another FC Madrid fan, so safe passage was ensured.

Zamora made his way to temporary exile via the ports of Valencia and Marseille to Paris. While in the French capital, Zamora gave an interview to the newspaper Paris Soir in which he described himself as a “one hundred per cent Spaniard.” While carefully avoiding expressing on what side his patriotic sympathies lay, Zamora said he believed he deserved to be better treated by some of his compatriots than to be made to fear for his life. He then journeyed to Nice, where he played for a time with his old friend Pepe Samitier, El Sami, the other star soccer player who had transferred from FC Barcelona to FC Madrid before the Civil War. El Sami’s escape from the “reds” also entered the mythology of the conflict, thanks to the newly created sports paper Marca. It gave full coverage to Samitier’s narrow escape from arrest, his days in hiding, and his eventual arrival in French territory “with two suits, a lot of hunger, and exhausted.”

There were other stories of escape and survival. For example, Spain’s star international soccer player Jacinto Quincoces served in the pro-Francoist Navarra Brigades and returned to his old club, Real Madrid, after the Civil War. Paulino Alcantara, the FC Barcelona star of the 1920s who retired from soccer to become a doctor, was on a death list for his alleged right-wing sympathies but managed to escape Republican-held Catalonia, the day after the military uprising, and made it across to France, before eventually returning to a life of retirement under Franco’s rule following a brief and uneventful spell as coach of Spain’s national team in 1951.

Not everyone, by any means, had such luck. Nearly 1 million Spaniards died in the Civil War. They included soccer officials and players who were executed or shot in battle, mostly not because they had worn the colors of any particular club but because they were associated with the enemy side. The victims came from clubs across the divided landscape. They included Gonzalo Aguirre and Valero Rivera, former vice president and treasurer, respectively, of Real Madrid; Damien Cabellas, secretary of Espanyol; Angel Arocha, the Spanish international and FC Barcelona player; and Ramon “Mochin” Triana y del Arroyo, who played for Atletico and Real Madrid. Other “disappeared” players included Oviedo’s Gonzalo Diaz Cale and Deportivo La Coruna’s Barreras and Hercules FC’s Manuel Suárez de Begoña, a former player and coach. In addition, at least four club locations suffered major damage: Real Madrid’s Chamartín stadium, Betis’s Heliopolis stadium and administrative offices, Oviedo’s stadium, and FC Barcelona’s social club and archive.

Few personal stories in the history of Spanish soccer sum up the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War as that of Josep Sunyol, elected member of the Catalan parliament and president of FC Barcelona. His last act as club president was on July 30, 1936, a few days after the outbreak of the Civil War, when he presided over an emergency meeting of FC Barcelona’s management board. He then drove south to Madrid and up into the nearby Guadarrama hills. He was visiting some Catalan militias who were defending the Spanish capital from the military insurgents when he lost his way and drove into hostile territory. Sunyol was detained and shot on August 6, and his body was thrown into an unmarked grave.

Although his body was never found, Sunyol was posthumously prosecuted for “political crimes” on September 28, 1939, by the Francoist state that had emerged victorious from the Civil War. Two months later an official report condemned Sunyol the politician and president of FC Barcelona for being anti-Spanish.