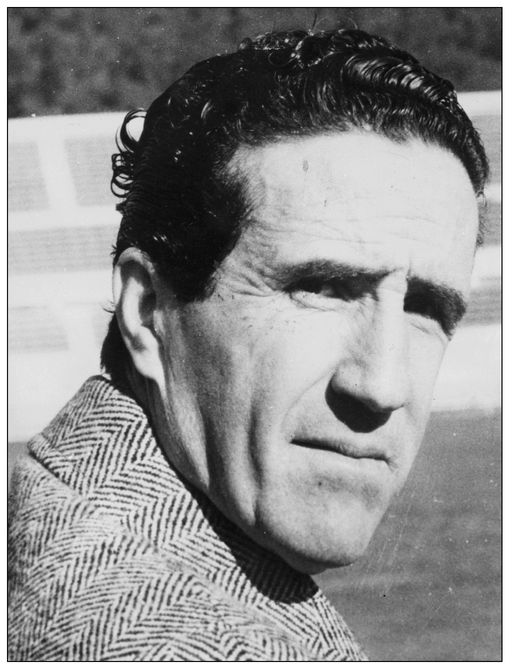

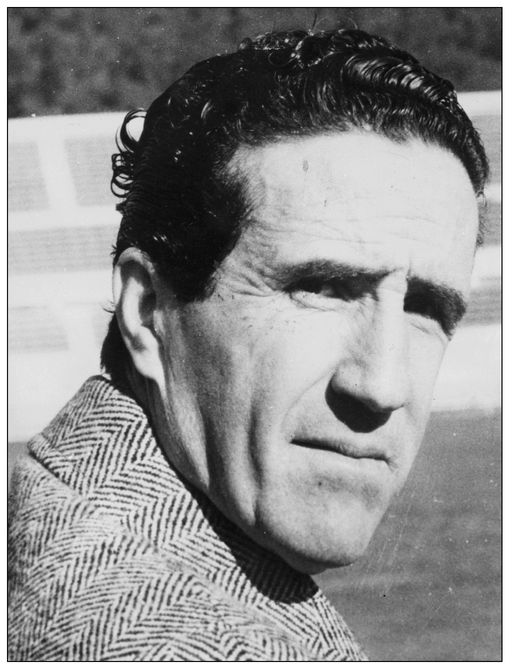

Helenio Herrera: “We are going to win”

CHAPTER 19

Herrera, the Magician

In a period of twelve years, between the World Cup of 1950 and the World Cup of 1962, Spain’s national squad appointed sixteen coach-managers, none of whom had the talent, organization, or vision to draw on the best from club soccer and transform it into a competitive squad capable of winning titles. Perhaps the one who did, Helenio Herrera, who served as Spain’s national coach between 1959 and 1962, proved too arrogant a personality and too divisive in his tactics to ensure a truly national enterprise. While individual clubs enriched the game they played with foreign imports and the lessons they learned from a variety of talented coaches, Spain as a soccer nation would grasp only belatedly the foreign tricks and spells with which it had been briefly dazzled during the tour of San Lorenzo de Almagro. Of Herrera’s many claims to fame, few can be as negative as the fact that he alienated both Alfredo Di Stéfano and Ladislau Kubala, two of the greatest figures in the history of Spanish soccer.

Herrera was a nomad who, at his best, brought a magician’s touch along with a strong personality to the profession of soccer manager-coach. He was born in Argentina to Spanish immigrants—his father was an exiled anarchist. When he was four he immigrated with his parents to Casablanca, where he adopted French citizenship. Herrera would later claim that he learnt what he needed to know about soccer—his school of life, as he called it—as a boy growing up in North Africa, mixing and playing with Arabs, Jews, French, and Spaniards.

During his two-year stint at FC Barcelona (1958–1960), he used his powers of psychology to motivate a team that all too often seemed overladen with its own self-conscious sense of history and an underlying inferiority complex with respect to its rival Real Madrid. The way Barca emerged from its periodic doldrums and flourished under Herrera was so quick that it fueled conspiracy theories in Madrid of trickery, secret rituals, even illicit drugs, although much of the negative media coverage was fueled by the coach’s unashamed mercantilism. Nonetheless, he won the respect of his players, with the exception of the aging Kubala, whom he judged surplus to requirements.

As one of the younger Barca players and a future Spanish international at the time, Fusté recalled, “Herrera was soccer’s psychologist. . . . [H]e was very good at motivating his players. . . . [H]e would convince them they were better than the opponent. . . . He got me into play when I was seventeen. . . . I looked up to much older players like Kubala and Evaristo and Ramallets as if they were gods. Herrera knew how to make the best use of the resources at his command.”

Herrera brought Spanish and Italian club soccer into the modern era of coaches stamping this style and worldview on their players and in the process becoming the first manager to collect credit for a team’s performance. Up to that time managers were more marginal, with the exception perhaps of prewar examples of eccentric Englishmen such as Athletic’s Mr. Pentland or fearless Irishmen such as FC Barcelona’s Patrick O’Connell. During the 1950s teams were better known for their players, such as Di Stéfano’s Real Madrid, than their managers. Yet Catalans remember the Herrera era, while Inter FC during the 1960s is still referred to as Herrera’s Inter.

He came to be popularly known as “the Magician” on account of his innovative psychological motivating skills, which some of today’s most successful coaches like Pep Guardiola and José Mourinho were destined to emulate. His pep talks would be punctuated with phrases like “He who doesn’t give it all doesn’t give anything.” Herrera was disdainful of other managers in Spain for their failure to engage with players and to bring about a real change in their attitude. His prematch warm-ups, like his training sessions, were intense affairs, and his press conferences usually controversial, as were his prematch preparations. After providing his players with a cup of tea made up of spices and herbs only he knew the true identity of, Herrera would gather his players around him in a circle. Then, throwing the ball at each in turn, he would scream a question, looking each player directly in the eyes. “What do you think of the match? How are we going to play? Why are we going to win?” he would ask. The questions gathered in speed and intensity as he went around the circle. Then as a collective frenzy appeared to reach its climax, the circle would split and the players sprint before returning to the fold, at which point the team would shout, “We are going to win!”

Herrera encouraged superstition, which he believed complemented the traditional Virgin cults to which most Spanish clubs were linked because of the Catholicism of a majority of players and fans. He found a susceptible target of his own tricks in the case of the Galician-born Luis Suárez, the attacking midfielder nicknamed El Arquitecto (The Architect) for his visionary passing and explosive goal-scoring ability. Galicia has never boasted as many soccer stars as other major regions of Spain. After Suárez, only Real Madrid’s Amancio would lay claim to enduring fame, and they both chose at an early stage in their careers to emigrate to bigger non-Galician clubs. Other Spaniards say that the Gallegos lack the strength of Basques, the imagination of Catalans, the courage of Castilians, and the mischievous artfulness of Andalusians. So the popular soccer joke goes: “An Andalusian kicks the ball out of play and smiles. The Gallego takes twenty minutes to recover it.”

But Suárez was different. He was not only a fine and creative inside-forward, the first Spanish-born player to be voted European Soccer Player of the Year in 1960, but he was also deeply superstitious. Thus, while looking on Suárez as Di Stéfano’s “legitimate heir,” Herrera played on his star player’s belief that a glass of wine, accidentally spilled during a prematch meal, augured well for his goal-scoring chances. When Suárez wasn’t looking, Herrera would give his wine glass a good tap and exclaim in a loud voice, “What a pity we’ve ruined the tablecloth!” Suárez would then immediately run up, dip his finger in the spilled wine, and then touch first his forehead and then the tip of his shoe.

Despite his tricks, Herrera had a genuine knowledge of the game and how it could be played best to entertain and secure victory. Herrera experimented with some innovative attacking soccer, using fullbacks as wingbacks defensively supported by the libero, or center-half stopper, to launch faster counterattacks and turn some of the easier games into goal sprees. But he also knew how to close down opponents by having the sweeper stay behind the defense, with the rest of the team marking man-to-man and counterattacking on the break. Herrera claimed that his tactics were slightly different from the catenaccio , or cult of defense, that came to be identified with Italian teams with a reputation for negative play. He himself liked to use, among his options, a system whereby the center backs in front of the sweeper were markers, while the fullbacks had to be able to run with the ball and attack.

Herrera was full of praise for two foreign signings by Barca, the Hungarian Kocsis—the “Golden Head” who also had a sure touch and strength of foot, and Czibor, fast on and off the ball and similarly skilled in goal scoring. While Czibor liked to describe himself as the “engineer among the workers,” Herrera insisted on a collective team effort. A competitive spirit, strength and speed, and technique were what constituted a winning formula. In an era of foreign imports, arguably Herrera’s greatest contribution to the health of the Spanish league was in following the example of Athletic Bilbao and encouraging Barca’s youth system—players like Olivella, Gensana, Gracia, Verges, and Tejada. “We owe them many of our victories; they played not just with class but with an absolute dedication to the club colours.”

When some three years before he died in 1997 Herrera was visited at his Venice palazzo by author Simon Kuper and was asked to talk about his time in Spain, Herrera explained that he played his “tricky foreigners in attack”—Kocsis, Villaverde, Czibor, and so on—while basing his defense on homegrown talent, whom he referred to as “my big Catalans”: Ramallets, Olivella, Rodro, Gracia, Segarra, Gensana. “To the Catalans, I talked ‘Colours of Catalonia play for your nation,’ and to the foreigners I talked ‘money.’”

Herrera moved from FC Barcelona to Milan’s Internazionale in 1960 where he continued to also coach the Spanish squad. As things turned out, it was Galician-born Luis Suárez, neither a Catalan nor a foreigner, who ended up following in Herrera’s footsteps in the same year for 250 million Italian lire in the world’s most expensive transfer deal.

Herrera’s soccer career involved him in coaching six Spanish clubs, including Barca, and his spell as a coach of Spain that was to last from 1959 to 1962. He was in this post when in May 1960 Franco’s personal intervention forced Spain’s withdrawal from its quarterfinal matches against the Soviet Union in the first-ever European Nations Cup. The ties had been preceded by growing optimism in the Spanish camp after convincing victories in earlier qualifying matches against Poland and Yugoslavia and similar impressive victories in two friendlies, 3–1 against Italy at the Camp Nou and 3–0 against England at the Bernabéu, all under the management of Herrera. He had taken charge of the Spanish squad in 1959 and from the outset counted on such talent as Real Madrid stars Di Stéfano, Gento, Del Sol, Barca’s Luis Suárez, Ramallets, and Segarra as well as Joaquin Peiro and “Txus” Pereda, the attacking midfielders then playing for Atletico de Madrid and Sevilla, respectively.

Herrera convinced his men they would beat the Russians and go and secure the title. Yet Franco quashed whatever dreams this fusion of the best of Spanish club soccer may have had of European soccer glory by not allowing the squad to play on Soviet territory and insisting that both legs be played on neutral territory—a request that Moscow declined. Franco was partly influenced by consideration for Spanish veterans of the World War II Blue Division who had fought and suffered with the Germans on the eastern front and some of whom were reportedly still detained in Soviet concentration camps. But he later claimed that what ultimately led to his decision were the detailed police reports he received warning that the Soviet media were predicting huge support not just in Moscow but also at the Bernabéu for the Russian team. Franco smelled a communist conspiracy: a Soviet-led propaganda exercise aimed at exposing the Spanish regime’s unpopularity among exiles from the Civil War and surviving supporters of the Republic. This combined with a Russian request that the Soviet anthem be played and the Soviet flag be flown in the Real Madrid stadium proved altogether too much for Franco, and his appointees in the Spanish Soccer Federation—all Civil War comrades—did as they were ordered and withdrew the Spanish team from the competition.

The background to the controversy was never reported in Spain’s highly censored media at the time other than to belatedly try to shift the blame to the Soviet Union for insisting on playing on neutral ground. The row was taken very badly by some of the players, who privately resented such a blatant intrusion of politics into their sporting activities. As the Spanish international Txus Pereda told me in an interview conducted in 2010 (he was to die of cancer a year later):

We all returned home with a huge sense of sadness. I and the others had never been to Russia. We were genuinely interested in visiting a country that was a mystery to us and most Spaniards who had not gone into exile in the Civil War or fought there in World War II. It was also a great opportunity to play in a major competition final. I remember we are all gathered in the Spanish Federation offices in Madrid when they suddenly told us the match was off and we could all go home. It was all because of [political] pressure. Some ministers said yes, others said no, but it was Franco who was the boss, and he said no.

Herrera expressed his disappointment publicly on behalf of the team—without directly raising the issue of politics, still less blaming Franco. The official rumor mill suggested that this had little to do with any sense of patriotic opportunity or love of soccer but rather the loss of the financial bonuses Herrera had been promised by the Spanish Federation as an incentive to beat the Russians. Abroad it did little to improve Franco’s image among his critics. The London Times condemned what it described as Franco’s arbitrary and blatantly political coercive act that had violated the founding principles of the International Olympic Committee and FIFA. The newspaper suggested, not inaccurately, that Franco was making a point about Spain’s credentials as an anticommunist Cold War warrior as a way of impressing his military and commercial ally, the United States. It certainly had very little to do with soccer.

Herrera survived for another two years as manager of the Spanish squad, but he made as many enemies as friends, and the former eventually caught up with him. The Argentine initially courted criticism for dropping Kubala from Barca first and then from the national squad, justifying the move on loss of form and lack of discipline linked to the Hungarian’s heavy drinking.

Herrera forced out not only Kubala, but also another legend of Spanish soccer—Pepe Samitier, the former star player–turned–technical director of FC Barcelona. After a row with Herrera, Samitier moved to Real Madrid, where he had as many friends as in the Catalan capital, not least Franco himself, and where he harbored an enduring grudge against the Argentine. By the time Spain qualified for the World Cup in Chile in 1962, Herrera had become, as Alfredo Relaño puts it, the “baddy of the film . . . for many an innovator, for others a real antiChrist of soccer.”

On paper the Spanish squad that qualified for the World Cup in Chile in 1962, with Herrera as coach, could only impress, such was the talent and experience displayed. It included four nationalized foreigners—Di Stéfano, the Uruguayan-born Real Madrid central defender José Santamaría, Puskás, and Barca’s Paraguayan-born striker Eulogio Martínez—together with a coterie of homegrown stardom that included Gento, Collar, Peiro, Garay, Adelardo, and Del Sol. Yet Spain did not get past the first round where it was grouped together with Mexico and the two eventual finalist runners-up Czechoslovakia and Brazil, which won the championship.

As Brian Glanville has written, the component pieces of the Brazil team had “sprung apart, then strangely and steadily come together again.” During the four years since they had last won the World Cup, two key Brazilian players had played at the club level in the Spanish Liga with contrasting fortunes. Vava, who scored twice in the 1958 final, went on to have two successful seasons with Atletico de Madrid. The other was Didi, one of the few foreign stars brought in by Bernabéu who did not prove a success at Real Madrid, partly because he never seemed to be quite up to the energy and speed of his teammates and partly because of personal problems involving his wife. She was a journalist who claimed that Di Stéfano was jealous of her husband and mistreated him. Di Stéfano blamed Didi for not fighting enough for the ball and losing it too easily. “The Bernabéu stadium likes quality, but it also values effort, work, commitment—it wants a battle. It’s a public that is used to winning and to win you have to fight,” Di Stéfano once said. In other words, Didi was a lesser being.

Arguably, bad luck rather than bad soccer conspired against Helenio Herrera’s Spanish squad. It got off to a faltering start, losing 0–1 against the Czechs, their early pressure blocked by a solid defense, their flow of play increasingly interrupted by brutal tackles that crippled Herrera’s stars and led one of them, Martínez, out of pure frustration, to lash out with a kick to an opponent’s stomach. In the next game, against Mexico, the Spaniards rediscovered their rhythm. Again a strong defense resisted the Spanish pressure, but this time the gods were smiling, and Peiro scored the winner in the final minute.

In their final game in the group, Spain faced Brazil. The Spaniards needed a draw, if not a win, to qualify. It was a game in which Didi had planned to take his revenge on Di Stéfano, but Di Stéfano was left out of the Spanish team after pulling a muscle. Before the tournament got under way, Di Stéfano’s father turned up with a “magic” liniment, but to no avail. A conflict of egos had led to an enduring rift between Di Stéfano and Herrera. As the then young Spanish international Fusté later recalled, “Di Stéfano was a guy who liked to lead, to be the boss, and he wanted to go on being the boss. The problem was that Herrera wanted to be boss as well, and there wasn’t room for both of them.”

For the game against Brazil, Herrera took a major gamble, which was also a questionable statement of self-belief, by making no fewer than nine changes from his original eleven. He dropped two star forwards, Del Sol and Suárez, his goalkeeper Carmelo, and his center-half Santamaría. Instead, he drew up a traditional attacking five with Puskás and Gento alongside three Atletico de Madrid players led by Peiro. In what some commentators regarded as one of the best games of the competition, Spain played with commitment and flair. Those watching the game included the seasoned English journalist Brian Glanville, who noted that for the first hour of the game, Spain played a defensive game that had Brazil at full stretch, before a swift counterattack led by the nationalized Puskás helped create the first Spanish goal. Spain kept its composure and their lead for another thirty-eight minutes, at which point Brazil equalized. Then with four minutes of normal time left, Brazil scored the winner. As Glanville himself concluded, it was a very near thing and arguably a “manifest injustice to Spain,” which he judged the best-organized and most motivated team on the day. Nevertheless, Spain’s resulting elimination from the 1962 World Cup reignited a national debate about the future of Spanish soccer, which brought with it some nasty prejudices from Spain’s darker past.

Nationalist attacks focused on the foreign influence that had formed part of the Spanish expedition. The state-controlled Spanish sports daily Marca led the charge, claiming that Spain had underperformed as a result of not being sufficiently Spanish in selection and spirit. While conceding that nationalized foreign players like Di Stéfano, Puskás, and Kubala and managers like Daucik (Kubala’s Hungarian father-in-law), the Paraguayan Manuel Fleitas, and Herrera himself had added “color and excitement” while also helping clubs like FC Barcelona, Real Madrid, and Atletico de Madrid win domestic and European competitions, the newspaper argued that the same foreigners were blocking the development of homegrown talent. “Even worse, the national team is now so full of foreigners and so conditioned by foreign tactics that it no longer plays like a team of real Spaniards, with passion, with aggression, with courage, with virility, and above all with fury,” said Marca.

Not even Spain’s star international Luis Suárez, a Spaniard born and bred, escaped criticism, the fact that he had chosen to leave his country to play in a foreign club held against him as antipatriotic—or so it seemed to his detractors. As for Herrera, he made so many enemies along the way during his time in Spain that he, above all others, became the target of unbridled criticism painting him as a mercenary with no loyalty but to himself.