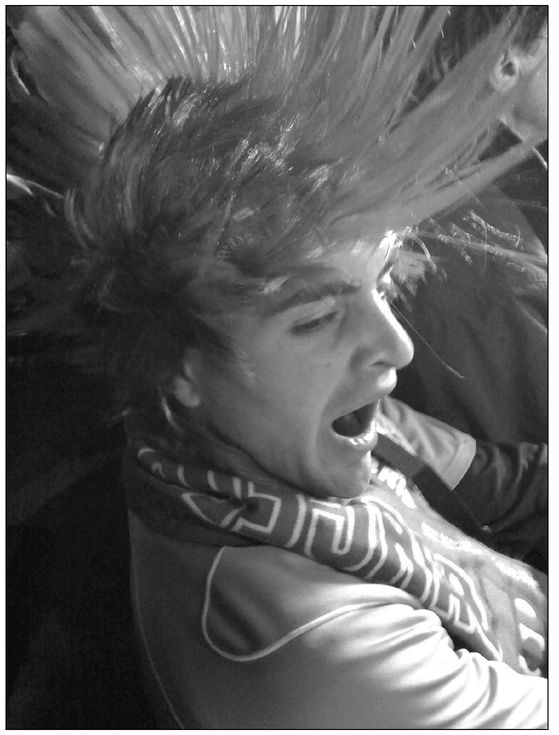

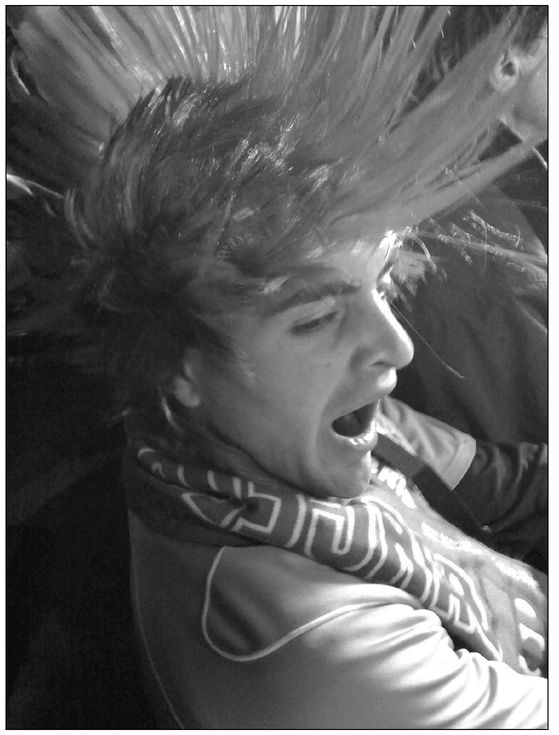

A Barca fan: “More than a club”

CHAPTER 21

Rivals

It is perhaps as good a point as any in the ongoing narrative to examine more closely the rivalry between the two giants FC Barcelona and Real Madrid and the one key phenomenon that has straddled much of the history of Spanish soccer and been fundamental to both its evolution and its popularity. The infamous game between the two clubs in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War in Real Madrid’s stadium in Chamartín during which an atmosphere of visceral hatred led to the visitors being thrashed 11–1 was the first of a series of postwar controversial encounters that would develop as part of world soccer’s most intense and enduring club rivalries. It was a rivalry that, while having its roots in politics and culture, became driven by a momentum of mutual creation. It fed on itself, reflecting the growing popularity of soccer as a sport, while manifesting itself most violently at times of maximum political anxiety.

The bad blood that ran through every encounter remained a constant for more than a half century. There was rarely an encounter when both sides could claim a level playing field. It did not matter whether the game was played in Madrid or Barcelona; each match was intensely partisan. The occasion when fans set aside tribal loyalties and applauded a player because of how well he played, not because of the shirt he wore, was rare. I have witnessed this only twice—when FC Barcelona’s Ronaldinho and later Messi received a standing ovation from the home fans at the Bernabéu in recognition of their outstanding play. By contrast, one of the most abusive incidents I can recall witnessing in any gran clasico was when Figo returned to the Camp Nou for the first time since November 2002 when he changed his club colors. While at FC Barcelona, Figo had made 172 appearances for the Catalans and won the league twice. But he had committed the ultimate sin of transferring from FC Barcelona to Real Madrid, setting a new record transfer fee of £37 million. The cacophony of jeers and expletives, together with the cans, lighters, and other loose missiles that accompanied the Portuguese international’s every move, climaxed with a severed suckling pig’s whole head being thrown at him by local fans as he prepared to take a corner kick.

Through much of the history of this rivalry the referee stood accused of being a fellow conspirator rather than an arbitrator, hated by one side as much as he was loved by the other. As a general rule the loser would always feel cheated, while FC Barcelona has tended to show itself as less magnanimous in victory and a worse loser. In the past this might reflect a certain inferiority complex FC Barcelona developed during Real Madrid’s golden years of the 1950s, when its rival laid justifiable claim to playing the best club soccer in the world. In more recent times, roles were reversed when José Mourinho characterized his early days as manager of Real Madrid by blaming the supremacy of FC Barcelona on too much diving by the Catalans and too many unjustified decisions against the players in white.

Battle lines were first drawn in the Spanish capital in 1912, when twelve minutes from the end of one of their first competitive games against Real Madrid the whole FC Barcelona team abandoned the game, claiming that the referee was against them. During the 1960s, Real Madrid adopted a particular dislike for British referees, holding one of them in particular responsible for disallowing goals by Di Stéfano and Gento and giving FC Barcelona a disputed penalty. On June 6, 1970, a young, inexperienced referee from San Sebastián, Emilio Guruceta, was in the eye of the storm when he gave a controversial penalty to Real Madrid during a second-leg quarterfinal tie in the Spanish Cup. The penalty was awarded after Real Madrid’s Manolo Velázquez seemed to have been brought down well outside the box. The stadium erupted in protest. There was an unprecedented field invasion and running battles with riot police.

Although Franco would live and rule for another five years, this was a defining moment in Spanish soccer. The Guruceta case, named after the referee who made the wrong call in Real Madrid’s favor, was the first time that Spanish soccer had gotten out of the dictator’s control. Until that moment, by allowing FC Barcelona to function, he had divided and ruled, exploiting the political confusion of the Catalans, many of whom had fought for him in the Civil War. His intention was never to prevent Barca from winning titles, but to see Spanish soccer become an ever more popular sport thanks to the rivalries of its two great clubs.

It is a conflict that I have followed closely as long as I have been a soccer fan. It is a subject that has taken up much of my childhood, youth, and professional life, and my experience of it has been from the perspective of both camps, having been born and brought up in Madrid, while spending family vacation time in Catalonia and sharing much of my working life in Spain between Barcelona and the Spanish capital.

It was such a background that no doubt led me to cross paths with the Irish actor Ardal O’Hanlon in 2006, among the countless memorable encounters I have had along my journey into Spanish soccer. I had never met Ardal when I received a phone call from him out of the blue early that year. The comedy series Father Ted in which O’Hanlon plays a goofy young Irish priest called Father Doogall had long been a favorite of mine, so I felt honored, if surprised, to hear from him. It turned out Ardal was doing another television series—this time with a slightly more serious bent, on great soccer rivalries, and wanted me to help him out in Spain. It was an offer I didn’t even consider refusing, and within hours I was sharing some tapas and vinos with Ardal and his production team in Barcelona’s Old Quarter, near the cathedral.

Ardal has the disconcerting personality of all good comedians—an intensely private person offstage, both thoughtful and intelligent and far from brash or outspoken. While refusing to be tagged as political, both his father and his grandfather were deeply involved in the politics of the Irish state, which gave him a special insight into the divided politics of Spain and its soccer. Ardal was also a keen observer of the ordinary daily grind of life—as well as its peaks and troughs. His instinctive irreverence was underpinned by intelligence, laughter mixed in with occasional dark moods. Of his talents not just as a television actor but as one of Ireland’s (and the UK’s) most gifted stand-up comedians, I was aware. More of a discovery was his passion for Spanish soccer, and one club in particular. “I’ve been infatuated with soccer since the age of four,” Ardal admitted. It dated his infatuation to 1969. “First it was Leeds, then in 1974 it was the Dutch, and then when Cruyff went to Barcelona it was Leeds, Holland, and Barca!” He went on: “The infatuation grew and then fell off for a while—when I discovered girls and ‘other things’—but the dream of visiting the Camp Nou never quite disappeared. The first time I came here was about ten years ago on my honeymoon. It was my wife’s first-ever soccer match, and she loved it.”

He reminded me that my own infatuation with the stadium had begun when on a first visit as a young television researcher in 1976 I had watched Cruyff lead his team out to play in a game against Athletic Bilbao and the stadium filled with Catalan and Basque flags. It was the first time that such a blatant display of non-Spanish nationalist loyalties had happened in a soccer stadium since the Spanish Civil War. Franco had banned both flags throughout his dictatorship. Years later I ended up taking one of my daughters to the Camp Nou for the first time, and she loved it. It proved a happier experience than for her younger sister, who on another occasion had to put up with the racist abuse from Chelsea hooligans at Stamford Bridge because she supported Barca in a Champions League match.

But back to Ardal. I was struck by Ardal’s familiarity with relevant Spanish history—or at least its mythification—which he commented on with his comedian’s eye for the telling anecdote and knack for synthesis. “That’s Columbus’s statue over there,” he observed while walking down by the harbor, “but you won’t find him pointing toward the Americas—this being Barcelona, he is pointing toward the Mediterranean. The Catalans claim Columbus as one of their own, which is a bit of a surprise considering it was largely his fault that Catalonia went into a very long and steep decline. Columbus opened up the new trade routes to the West, but the king and queen of Spain forbade the Catalans from using them. Thus Barcelona was thwarted, nor for the last time, by the dastardly Spaniards. But they refuse to lie down.”

Over the next days of filming we were both on a mutual learning curve and forged a strong friendship around soccer that belied our age difference—I was twelve years older than he was. Between us I think we tried to illuminate some truths as well as dispel some myths. The fact that neither of us had parents who were particular soccer fans and thus without a tribal loyalty helped us approach a divisive subject through a more or less objective lens.

So we began to share some unquestionable truths. Of all the regions that constituted Spain, it was the Catalans that historically had been the most forceful in asserting their identity. No matter that their version of history from medieval times onward exaggerates the extent to which Catalonia was once a nation as opposed to a region. History is perhaps nowhere more argued over and with such passion than in Catalonia, where it is a political weapon in the battle for identities. Two centuries ago the English chronicler of Spain Richard Ford commented, with some foresight : “No province of the unamalgamated bundle which forms the conventional monarchy of Spain hangs more loosely to the crown than Catalonia, this classical country of revolt, which is ever ready to fly off.” The Catalans certainly had a legitimate grievance based on the belief that their history differed from that of the myth of a united nation-state ruled from Madrid, and this had fueled one of their enduring passions.

One cannot begin to understand Spanish soccer’s greatest club rivalry outside the context of Catalonia’s relationship with the rest of Spain. Or to put it another way, one cannot begin to understand FC Barcelona’s perception of Real Madrid as the main enemy without taking in Catalan politics, culture, and history and the interrelationship of all three with soccer. Much of the history of Catalonia, as viewed by a majority of FC Barcelona fans, is a story of humiliation and frustration, the aspirations of this region curbed and stomped on by the centralizing tendencies of Madrid, the potential of Barcelona as one of the great capitals of the Mediterranean never fully realized, and the perceived close links between Real Madrid and the center of power in the Spanish capital.

Some of the facts of Catalan history are fairly straightforward even if seen through the mind of a comedian like Ardal O’Hanlon and hard to take too seriously. “You can feel the spirit of Wilfred the Hairy here,” proclaimed Ardal later one afternoon in the Camp Nou as local fans began to converge for the latest Barca–Real Madrid encounter, with their Catalan and Barca flags and shouting in one uninterrupted cry “Visca Barca Visca Catalunya” (Catalan for Up with Catalonia, Up with Barca.). Somewhere in the stadium someone had lifted a large poster with the manifesto CATALONIA IS NOT SPAIN.

Catalonia was recovered from the Moorish occupation in the early eighth century, long before much of the rest of Spain, and had its various fiefdoms united under an inspired count called Wilfred the Hairy (he was indeed called that because he was a heavily bearded man, as he is remembered to this day in statue form and the history books of Catalan schoolkids). While considered by some the founder of Catalonia, this medieval warrior was still a vassal to Charles the Bald (who indeed lost his hair in early adulthood for reasons unknown). It was another Catalan warrior count, Borell the Second, who finally broke his vassalage from the intruding French king, Hugh Capet, in what Catalan nationalism would later claim was the birth of political Catalonia in 988. For then on the counts of Barcelona became, through a marriage in 1137, the kings of Aragon, who would later go on a conquering spree that extended south as far as Alicante and east to the Balearics and beyond to Sardinia, Sicily, Corsica, and southern Italy—Catalonia’s very own days of imperial glory.

Fast-forward to the end of the Spanish Civil War: thousands of Catalans imprisoned or executed or forced into exile by Franco. At this point you may well ask what all this history has to do with the militancy that drives soccer’s greatest rivalry. Rest assured that Barca fans take their history very seriously, however mythological. During the late 1990s I toured Spain in a bus filled with one of FC Barcelona’s most radical group of fans. They called themselves the Almogavers. Their T-shirts and banners depicted medieval knights in full armor. So what was all this about, I asked Marc, the young secretary of the fan club. “The Almogavers were Catalan soldiers of the thirteenth century [actually they were mercenaries for the king of Greece] who conquered the Mediterranean. They’d go into battle on foot, holding their swords, and fight off whole armies on horseback.”

Then Marc, together with some his mates, broke into the Barca anthem, “Tot el camp es un clam, som la gente blaugrana” (The whole stadium is a rallying cry, we are the people of red and blue)—the Barca colors, blue and red, the colors every club fanatic will insist are the colors of freedom. “We want Barca to conquer Europe just like the Almogavers,” Marc will go on to tell me. He is holding a small banner bearing the words Barca i Catalunya sempre al nostre cor (Barca and Catalonia always in our hearts). “It’s one and the same thing. That’s what drives me. I’ve done so much for Barca, missed my exams, missed a whole year at college. You might say I’m fanatical. I like to consider myself someone who loves Barca with all my heart. If that’s fanaticism, then I’m a fanatic.”

That such loyalty is often mixed up with a visceral dislike of Real Madrid has to do with the fact that long after Wilfred the Hairy and Columbus had been buried, things got far worse for Catalonia before they got better, first with the united Kingdoms of Aragon and Castile moving the balance of political and economic power toward the center and then in 1714 the Bourbon regime of King Philip V depriving the Catalans of their local parliament and other rights, such as the power to raise their own taxes. Yet Catalonia was to prosper economically over the next two centuries, exporting wool and paper and embracing the Industrial Revolution before most of the rest of Spain, providing jobs for thousands of migrants from other regions and in effect subsidizing the more backward areas of Spain. Catalonia came to look at the rest of Spain, and Madrid in particular, not only as arrogant, and intolerant, but also ungrateful.

FC Barcelona drew its strength from troubled times, giving the region as a whole a necessary feeling of collective self-confidence. The collapse of the Spanish empire with the loss of Cuba in 1898 fueled Catalan nationalism. The birth of FC Barcelona at the start of the twentieth century made it early on a central focus of Catalan nationalism along with the reemergence of a Catalan nationalist party, parliament, and newspapers. “Barcelona became one of the most vibrant and wealthiest cities in Europe, home to the artists Gaudi, Picasso, Miró, and Dalí. Dalí entered a competition sponsored by FC Barcelona; Miró painted a poster for the club. FC Barcelona was a crucial part of Catalonia’s newfound optimism and prosperity,” enthused Ardal O’Hanlon.

It was all to change, though, after the Spanish Civil War. In 1942, for all this show of public self-confidence, Spain was a country politically divided within itself. Catalonia was once again denied its local parliament, Castilian was once again imposed as an official language, and the Catalan flag was banned. And although the management of FC Barcelona was handpicked by the regime, soccer provided an escape valve for suppressed emotions.

While a majority of Spanish soccer clubs were purged after the Spanish Civil War of political dissidents, and found themselves with little option but to recruit new members supportive of the new regime, FC Barcelona still managed to preserve an identity as a Catalan institution. The official postwar newsreels show the club’s stadium, Les Corts, as a crowded theater of orderly entertainment, with no antiregime flags or slogans or chants. But beneath the apparent conformity, a sense of resentment, revenge, and resistance persisted.

In 1947 Gregorio López Raimundo, the head of the Catalan Community Party, returned secretly from exile in France with a false passport and started going to Les Corts, both as a fan and as a political militant. He not only enjoyed the soccer, but also felt more protected from persecution in the stadium than he did on any street corner in Barcelona. As he told me many years later when I interviewed him about his years in clandestinity: “Out in the city, fascism was very visible—the names of the streets, the Falangist crests, the portraits of Franco, the flags. But in the stadium you were among the masses, and I felt—maybe I was imagining it, but I felt it all the same—that everyone around me was really antifascist deep down, at least in the stands. Maybe things were a little different where people were sitting; the club management was proregime, handpicked no doubt during the early Franco years but not the fans—they identified themselves with a democratic Catalonia.”

It was not until 1968, a year marking revolution in large swaths of the world, that FC Barcelona’s new president, Narcis de Carreras took it upon himself to give the club marketing department a dream motto: “Barca es mes que un club” (Barca is more than just a club). In other words, it could not be compared to any other soccer club, let alone Real Madrid, because it represented so much more in political, cultural, and social terms. Catalans might have been divided over exactly what Catalonia meant—was it a region or a nation—but from now on there could be no doubt about Barca. As Bobby Robson, one of its managers, would later tell me: “Barcelona is a nation without a state, and Barca is its army.”

The politics of Real Madrid do not lend themselves so easily to mottoes or manifestos. One of Spanish soccer’s most literate commentators, the Argentine-born former Real Madrid player and manager Jorge Valdano—no old Francoist he—once tried to explain this to me: “Real Madrid is a team that only thinks in soccer terms, not political or nationalistic ones. . . . I think that is a huge advantage it has over FC Barcelona, which thinks too much in political terms. The worst thing you can do to a soccer player is to give an excuse to justify his frustration.”

Undoubtedly, the 1950s were Real Madrid’s golden years, when everyone seemed happy, at least in the club. Barca fans console themselves to this day by claiming that one of the major stars, Alfredo Di Stéfano, was “robbed” by the rival in a questionable transfer deal that had a helping hand from the Spanish state. But the legend rests with Real Madrid as the first Spanish club not only to become champions of Europe but also to subsequently hang on to the titles over several seasons. To Real Madrid fans, old and young, it was Di Stéfano who gave them a sense of identity during a period of history when Spain remained relatively isolated in the world. He came to personify success on a global scale, something that during the 1950s could not be said of any Spanish company, let alone Franco. Di Stéfano, long retired, was asked once by Inocencio Arias, a former Real Madrid director and personal friend, what he thought defined the Real Madrid fan: “It wants the team to fight . . . it wants it to win . . . but it wants it to win first and then to play.”

During our stay in Barcelona, Ardal and I were not short of Catalans prepared to simply dismiss Real Madrid as Franco’s team. But Real Madrid fans who belonged to the first generation to be born after the Spanish Civil War and who did not share their parents’ pro-Franco inclinations feel insulted by this, even more so now that Spain has been a democracy for a while.

In a short memoir published in the Spanish newspaper El Pais in 1994, novelist Javier Marias recalls becoming a Real Madrid fan, in 1957, at age six, despite belonging to a group of friends many of whose fathers, like his own, were all anti-Franco. “The enthusiasm I felt for Real Madrid was mainly provoked by one man and he was called Di Stéfano—no doubt. But there was something else—Madrid was a club that neither cheated nor had fear and was blessed with drama. These may seem trivial matters, but in the city of my childhood everything else seemed to lack any worth and only designed to make you fear and everything was sordid rather than dramatic. Real Madrid was like an oasis, like the cinema on Saturday.”

But if Real Madrid provided a kind of sanctuary to those who did not consider themselves part of the Franco regime, it has tolerated long after Franco’s demise among its supporters those of a more politically extreme bent. I remember arriving at Munich Airport some years back with a group of Real Madrid fans and seeing a section of them arrested by the police under German’s anti-Nazi laws. On another occasion I decided to join a small group of Barca fans at the Bernabéu. As we arrived at the Real Madrid stadium, our small group of Barca fans had to run the gauntlet. The Utra Surs were waiting with their usual vocabulary of racist abuse against FC Barcelona black players and against Catalonia generally.

Nonetheless, it’s no use pointing, as Marias and others do, to the fact that prior to Di Stéfano, Franco ruled the country and Real Madrid never won a domestic championship, let alone an international one, as evidence that this was not the regime’s team—that there was no political fix.

The case for the prosecution against soccer “collaborators” even of Marias’s “liberal” ilk collected enough evidence to confirm generations of Barca fans in their prejudice. Real Madrid’s “black book,” or its history, according to its Catalan nationalist detractors, notes just how trusted Real Madrid was as an ally by the Franco regime when it played in Venezuela representing Spain in an international club tournament in 1952. “The behaviour of Real Madrid from directors through to players has been irreproachable in all aspects and they have left us with an unsurpassable impression of impeccable sporting good manners and patriotism,” commented the official state bulletin at the end of the tournament. No such assurance could be given to FC Barcelona, a club whose loyalty to the regime could never be taken for granted as long as there was a simmering undercurrent of Catalan nationalism that fed on feelings of injustice, resentment, and envy.

During the 1950s, years during which the Spanish national squad continued to underachieve and Spain remained relatively isolated internationally, Real Madrid, much to the chagrin of Barca supporters, helped promote an image of Spanish success overseas. Santiago Bernabéu’s club in effect converted itself, together with emigration and oranges, into Franco’s most important export. And because this was a period that saw the expansion of televised soccer across borders, it put Real Madrid firmly on the map as the representative of Spanish soccer at its best, with its mixture of foreign stars and homegrown talent playing creative, offensive soccer in a way no other club in the world could match.

The reputation that Real Madrid built up beyond Spain’s borders was already apparent in the 1955–1956 season, which marked the inaugural of a European Cup tournament that would prove its potential not only to get around the diplomatic barriers of the Cold War but also to raise the international profile of major clubs and their revenue-raising capacity. On the eve of the tournament’s first final in Paris, the Spanish embassy in the French capital hosted a reception that attracted an impressive guest list from the French sporting world as well as senior representatives from international bodies like FIFA and the International Olympic Committee. It was the best-attended reception the Francoist embassy had had since the days of the Spanish Republican government prior to the Spanish Civil War.

In the season before, FC Barcelona, with Kubala as its star, came to Paris and against Nice won the Copa Latina. But this tournament was restricted to southern Europe’s clubs and lacked a pedigree in the wider soccer establishment. It was the European Cup, the dream child of Gabriel Hunot, a former French international and the editor of the widely respected sports daily L’Equipe that established itself as the most prized trophy in world club soccer, setting a marker for a new age in which soccer became a matter of celebrity as much as success. The legend of Real Madrid as the most successful sporting institution in the world is bound up with it because no other institution can claim to have won it so many times—six successive championship victories between 1954 and 1960.

Such a record has been absorbed by Barca fans over the years, nurturing their loyalty rather than diminishing it, and ensuring that the rivalry between FC Barcelona and Real Madrid becomes more intense as each new encounter approaches. In 2006, four days before el gran clasico, Ardal O’Hanlon signed up as a member of the Barca soccer club. He called it the proudest day of his life, as good, probably better, than the day he got his first Irish passport.