Grace Cathedral

When I was five years old, I told my parents, “I'm going to be married in that church.” I was pointing to Grace Cathedral, a neoclassical Episcopalian monolith that sits on top of Nob Hill along with the Pacific Union Club (rich guys only) and the Fairmont Hotel. At five years of age, of course, I didn't know what denomination it was, who went there, or anything else about it, but it was big and beautiful, and it had my name.

In 1961, it seemed fitting that Grace Cathedral would be my matrimonial church of choice. My decision to marry was not sudden. Rather, it was a natural progression of events, seemingly the right thing to do at the time. But nothing predictable had real longevity during that turbulent era. My generation, educated by the best public school systems before or since, was busy gathering the ingredients for a cultural stew that would feed reactionary efforts right up through the millennium. So when you consider the diverse mass of information we were receiving during the time period between 1959 and 1962, and the evolutionary shifts that were occurring, it was probably inevitable that my first marriage would be temporary.

My parents, as yet unobstructed by their hedonistic daughter, had moved to a stately, fake Tudor structure covered with ivy and surrounded by ivy-covered neighborhood homes. My mother was doing volunteer work at Stanford Children's Hospital, playing bridge with the ladies, and taking care of my brother, who was a quiet but naturally busy nine-year-old boy. My father was chairman of the board at Weeden and Company, living a polite, unassuming existence. Jerry Slick's parents had become good friends with my parents, and the two families were in the habit of enjoying weekends together at the Slicks' beach house in Santa Cruz. My future husband, Jerry, had two brothers, Darby (author of the song “Somebody to Love”) and Danny (who avoided rock-and-roll silliness altogether). The rest of the Slick family comprised Jerry's mother, Betty, a housewife who drank her way through the family gatherings, Jerry's lawyer father, Bob, and a basset hound.

Our decision to marry was inevitable. Neat and tidy? Not yet aware of what “complete personal freedom” meant, I was evaluating the long-run specifies. Jerry was bright and, like me, twenty years old. We had the same friends, our parents already knew and liked each other, we'd gone to the same schools, had come from the same social strata, had the same ethics and family background, and lived in the same small town. Does that sound like the ingredients for the perfect tight-ass, fifties, arranged marriage? I bought it and so did Jerry.

Was there passion? Nope. Just cultural imposition.

“Will you marry me?” Nobody ever said that lovely, naive line. We just moved into the married state as if it was expected and irrevocable.

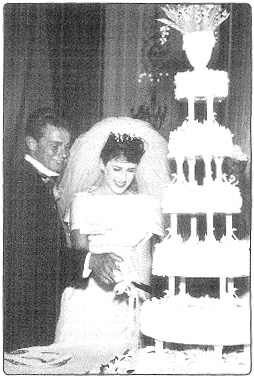

Jerry Slick and I slice through six tiers of tradition on our wedding day. (Ivan Wing)

Even though Cece and Jill St. John didn't know Jerry, my getting married was a good enough reason to get together and knock back a few cocktails. The night before the wedding, the three of us had a low-key, three-woman bachelorette party in one of the bars at the Fairmont. No drunken debauchery, just a mild high to fuel the girl talk. The next day, I had the kind of wedding that women love and men hate—big, dressy, and full of relatives and friends acting out lots of rituals. The reception was held in the Gold Room at the Fairmont Hotel with cake and champagne, and, to me, it all felt natural, no second thoughts, no regrets. Just another workout on the treadmill of tradition coming to a satisfying end at sunset.

Throw the bouquet and say “Good night, Gracie.”

After the standard honeymoon in Hawaii, we went back to the Bay Area. Then, at some point, Jerry decided, for reasons I can't remember, to go to San Diego State University. A beautiful area, San Diego was nevertheless populated by large groups of military-minded right-wing organizations. Jerry studied while I worked at a department store running a comptometer, a monstrous machine that calculates billing statements. For relaxation (?) we visited Jerry's cousin and her husband who weren't much older than we but were members of the John Birch Society. They were so right-wing, they made Charlton Heston look like a draft dodger. Although I wasn't particularly political at the time, it was hard to keep from laughing or just nodding off when they started with the here's-how-the-country-should-defend-itself harangue.

Our stay in San Diego was brief, thank God, because Jerry switched to San Francisco State at the end of the first semester. But I was still faced with a need to make money, and had no well-defined skills. The last stupid job I tried before my twenty-five-year rock-and-roll stretch, was modeling for the I. Magnin couturier department. Living with Jerry in a ninety-dollar-a-month shit-hole apartment in San Francisco with rats in the basement and unpredictable plumbing, I was expected to show up at the store each morning, change into a different four-thousand-dollar outfit every ten minutes, and float around, showing rich old women the latest in overpriced European designer wear. If they liked something I was wearing, the head of the department, Madam Moon, a bullet-faced frog with pretensions of social superiority, would measure their lumpy old bodies. Then, magically, with the help of her overworked seamstresses, she'd crank out a perfect copy of the original, transforming the outfit from a size six to a size sixteen. Mirrors don't lie, but denial systems rule—the old broads thought they looked fabulous and the I. Magnin coffers filled up.

One afternoon, an old dowager, cocooned in fur and rattling diamonds, came waddling over to me with her best four-martini tack and said, “My dear, you really do need to cream your elbows.” What the fuck was she talking about? How dare she discuss dry skin? Her entire body had freeze-dried so long ago, the addition of moisture would have been a life-saving event. And she thought I needed a lube job? I was twenty-two years old. The only time a twenty-two-year-old is going to look too crispy is if she's been in a four-alarm fire. I'm now fifty-eight and still refuse to put cream on my elbows. Stubborn perversity.

Ironically, while I was busy looking for a “real” job, I wrote my first song, without a clue that it was a precursor to my future. Jerry and I both got involved in a project with a mutual friend, Bill Piersol, an aspiring writer who'd written an interesting script treatment for an amateur sixteen-millimeter movie he named Everybody Hits Their Brother Once. A satirical comment on violence, Jerry filmed it while he was studying cinematography at San Francisco State, and it subsequently won first prize at the Ann Arbor film festival. I wrote a song for part of the succession of skits that made up that forty-five-minute reel, which was my initial experience at recording my own music—two layers of Spanish-style guitar picking that almost sounded like a cut from a professional soundtrack.

One of the best parts of returning to San Francisco was getting back in circulation with our original group of friends—with a few new additions. Darlene Ermacoff had married a man named Ira Lee, who was literally possessed by a monster IQ. A handsome and eccentric part-time model/full-time student, he'd been a Quiz Kid, a contestant on the forties radio show of the same name. It was Ira who once told me (accurately) that I was an empty-headed WASP, and he proceeded to suggest reading material that might remedy the problem. I learned a great deal from him, not so much because of my thirst for knowledge, but because I was absolutely fascinated by his wild-eyed delivery of arcane details on every subject imaginable. His outbursts of enthusiasm became one-man performances lasting well into the night, and although Darlene was used to them and went to bed more often than not, I needed a tutor and he needed an audience.

Darlene and Ira and Jerry and I used to take road trips to Mexico in an old station wagon, visiting the pristine beaches of Baja and, like all budding hippies, purchasing drugs. In those days, “south of the border” wasn't just a folksy phrase, it was the access route to a state of mind.