Anyone able to explain why E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial became the highest-grossing domestic release, then an unprecedented video success, selling 13 million worldwide, would probably stay mum and join Spielberg in millionairehood. (Anon. 1982; 1988a; 1988b)

Like Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which prevented Columbia’s liquidation, E.T. was an industry watershed, helping reverse a quarter-century decline in attendances.

The director himself was reportedly surprised. He supposedly regarded E.T. as a personal project (a luxury permitted by unusual creative freedom resulting from his commercial power, underlined by percentage shares accruing from his Raiders of the Lost Ark contract). E.T. was comparatively low-budget – modest effects, no major stars – clearly a factor in the astounding profitability that had Spielberg personally earning a cool million daily during 1982–83, from his ten per cent contract, and provided his 1988 Christmas bonus of $40 million (Adair 1982/83: 63; Sanello 1996: 110). This does not, though, account for the scale of the box office.

Promotion and publicity

Emulating the Jaws campaign, but with rights licensed for a fee rather than given away, E.T. was extensively promoted with tie-in merchandising, which alone grossed $1 billion, nearly half as much again as the film. However, while plastic figures in the breakfast bowl undoubtedly raised potential awareness, marketing cannot guarantee attendances. Indeed P&A budgets substantially exceeding a film’s production cost are hardly uncommon. Sometimes they pay off: The Full Monty (1997) grossed over $200 million after Fox spent ten times above its $3.5 million production budget on marketing; meanwhile Titanic (1997) earned the first billion-dollar gross after the same company’s spend on P&A almost equalled the record $200 million production cost (Glaister 1998). Nevertheless four flops counter each success, and failed campaigns are soon forgotten outside of the industry.

An attractive explanation is that E.T. was perceived as a children’s film (they were the merchandising market) – a family event, timed for the holidays (Independence Day in the US, Christmas in Britain). Matters are, though, less simple. Children’s tickets are cheaper so, in terms of raw numbers, less lucrative than adult admissions. Disney realised this years ago (leaving aside huge income from franchised products the films themselves advertise). Disney withdraws films within weeks of release. The video retail period is similarly limited. Thereafter, an aura of unavailability permits instant ‘classic’ status on later re-release, at which point serious profits kick in for relatively minimal additional cost.

Distributors working with Amblin, Spielberg’s production company founded in 1981, emulated Disney’s long-term strategy: E.T., out of circulation after a year, had a successful cinematic re-release prior to the video launch in 1988. But this is quite separate from its initial theatrical rentals. Furthermore, indications are that children were not the primary makers of E.T.’s success. The New York Times on 30 December 1982 reported a ‘significant increase’ in over-25s attending movies. The headline was unequivocal: ‘Adults Lured Back to Films by E.T.’

Effective promotion generates sufficient interest that a film becomes newsworthy in itself, attracting publicity independent of paid-for advertising. E.T. fuelled extensive speculation about the meaning of its success (it took $300 million in six months), which not only aroused curiosity among American adults but also filtered abroad before overseas releases. Distributors UIP calculated that over $30 million worth of free coverage was obtained for $6 million spent (Harwood 1995: 150).

Occasionally a movie engages fortuitously with existing cultural discourses. E.T.’s New York audiences queuing around the block comprised not families on weekend outings but heterosexual childless couples in their late 20s and 30s. Many belonged to the emergent Yuppie class, wealthy manifestations of enterprise culture, identified by power dressing, expensive eating tastes and designer accessories. Why were such people, who had apparently lost or never acquired the moviegoing habit, attending this film in droves?

Much was made of E.T. being a regressive fantasy. ‘We were crying for our lost selves,’ claimed novelist Martin Amis (in Baxter 1996: 245). Yuppies were supposedly escaping from stress into childlike spontaneity and freedom, a soft-centred alternative to the aggressive goal-orientation of their work and competitive leisure. More intriguing were suggestions that couples were deferring child rearing to advance their careers: the film’s emotionality gratified repressed parental instincts. A rumour alleged that Spielberg and Carlo Rambaldi, designer of the extra-terrestrial, visited maternity wards to take facial measurements from infants that nurses considered especially cute, and analysed data to produce the ultimate vulnerable baby. Whether or not this was true, E.T.’s cries at the start – which encourages empathy with the visitor through optical point-of-view shots and by portraying humans as shadowy, alien and frightening – resemble a newborn child’s. The wrinkled pinkish-grey creature, wired to monitors as he lies dying alongside Elliott (Henry Thomas) in what resembles an incubator, tended by masked medics, recalls a premature baby in intensive care. (The film elsewhere engages pre-conscious instincts. In the forest, for example, a fierce animal roar accompanies the irruption of scientists’ off-road vehicles.)

Reports of such an unlikely audience contributed to the narrative image – in which I am including expectations not consciously intended by publicists. Speculation reinforced word-of-mouth and reviewers’ recommendations about the alien’s uncanny credibility. (Four hundred and fifty preview screenings in the US confirm, nevertheless, that word-of-mouth was deliberately promoted.) Marketers ensured no clips showed E.T. in motion (Burgess 1983). Even the poster designers had not seen the film (Baxter 1996: 243). While dolls, puzzle books, candy wrappers and countless other epitexts, many unauthorised, made E.T.’s appearance familiar, trailers showed only his hand moving a branch (an optical point-of-view that inscribes his presence while keeping him off-screen) and his silhouette against the spaceship’s illuminated portal. Audiences had to pay to discover if the puppetry was really convincing. Meanwhile, fantasy filled the gap between desire and fulfilment. E.T. answered to spectators’ personal meanings even before they confronted him.

Other discourses sustained publicity, strengthening E.T.’s status as cultural event. The UK release coincided with telecommunications privatisation. To raise awareness of British Telecom’s shares flotation, billboards, similar in size and shape to cinema screens, displayed a starry sky and the slogan, ‘Give us time, E.T., give us time,’ a reference to the creature’s determination to ‘phone home’. Universal sued for copyright, generating millions of pounds’ worth of free publicity for both campaigns. (Sonia Burgess remarks that customers and potential shareholders were interpellated in the guise of E.T., suggesting an assumed identification (1983: 50).)

The 1980s saw domestic video become widely available, prompting predictable moral panic about imputed effects of any new medium. Debates concerning regulation spawned the phrase ‘pirate videos’ – a receptacle for lurid fantasies combining technological fears and images of vicious cut-throats (with xenophobic connotations of the South China Seas: for which read Asia, where the equipment originated). The paranoia, overlooking that most ‘pirates’ would be consumers copying illegally, was especially suggestive before anyone had seen one of these abominations. One of the first widely pirated products was E.T.

Poor copies, recorded from amateur equipment in a movie theatre, circulated widely in Britain. Students of mine remembered large gatherings in front rooms (videocassette recorders were expensive, so few households owned one) and recalled the mystique of ghostly monochrome images – the American NTSC coding being incompatible with Europe’s PAL. Apart from further publicity as a news item, this presumably contributed to cinema attendances as frustrated video watchers turned to the intended medium to complete the narrative image with colour, spectacle and high fidelity sound.

Reaganite entertainment? (reprise)

Reagan’s administration and Margaret Thatcher’s government in Britain were right-wing forces elected on a promised return to tradition. Reagan reasserted military confidence by invading Grenada, while Thatcher reversed opinion poll ratings from least to most popular prime minister by defeating Argentina in the Falklands. Given Cold War anxieties exacerbated by Soviet instability and Reagan’s ‘Star Wars’ Initiative, there may be justification for arguing that E.T.’s message of love and acceptance of difference fulfilled a compensatory function. This would be the reverse of 1950s science fiction, often now interpreted as projecting repressed fears of Communism and/or the Bomb. Such compensation – although it counters the sanctioning of foreign policy alleged against Raiders of the Lost Ark – confounds criticism that considers Hollywood fantasy automatically complicit with oppressive discourses.

Hysteria surrounding video regulation partly meshed with a perceived crisis in family values that Reagan and Thatcher exploited. Psychoanalysis suggests E.T.. might have formed part of, and benefited from this. Typically of mainstream narratives, it reenacts an Oedipal scenario for the spectator regressed through the Mirror Phase by the cinematic apparatus. Portraying children’s rebellion, from their perspective, against adult authority, E.T. ends with painless re-integration into the Symbolic Order.

The film begins with E.T. toddling childlike between trees, their size emphasised by music connoting religious awe. This idyllic scene (rabbits gambol unconcerned as aliens tenderly gather botanical specimens) represents unity, as the landing party’s hearts glow in mutual empathy, underscored by literal harmony, wine glasses reverberating to represent their warnings to each other. This is the lost Imaginary: the alien ‘family’ remain secure while close to what critics significantly call ‘the mothership’ (never so-named in the film).

Enter human scientists who wreck this paradise, led by a mysterious figure with keys jangling from his belt. They stand for all adults who, until E.T.’s apparent death, when the medics remove their masks and contamination suits, are presented similarly (apart from Elliott’s mother (Dee Wallace)): faceless, un-individuated, mostly male authority figures, shown in silhouette, from behind, or from shoulders to knees, from a child’s level. The keys’ association with phallic authority is unmistakable: repeated close-ups of them swinging at crotch level are the nearest a kid’s film could approach to representing male genitalia. The credits explicitly call the man Keys (played by Peter Coyote) (the name of Walter Neff’s older nemesis in that overtly Oedipal classic, Double Indemnity (1944)).

Elliott defiantly upsets his mother by referring to his father in Mexico with a girlfriend, prompting his brother Michael (Robert Macnaughton) to ask when Elliott will ‘think about how other people feel for a change’. The mother’s difficulty disciplining her children is linked to the father’s absence, suggesting mild family dysfunction. Nostalgia replaces Elliott’s aggression when aftershave on ‘Dad’s shirt’ evokes happy memories. As made clear when a scientist asks, ‘Elliott thinks its thoughts?’ and Michael replies, ‘No, Elliott feels his feelings’ – both terms echoing Michael’s earlier rebuke – the alien becomes Elliott’s surrogate father, socialising him by teaching consideration and setting responsibilities. Sarah Harwood describes E.T. as a parodic father who ‘uses the house for entertainment and servicing’, gets drunk, throws beer cans at the television, wears Elliott’s father’s clothes, and employs his tools (1995: 159; see also Heung 1983).

When E.T. goes ‘home’, however, another father intervenes. As E.T. lies dying, Keys taps Elliott’s oxygen tent to attract his attention, a close-up emphasising a two-fingered gesture already associated with E.T. looking through the branches. (Michael, who has repeatedly claimed the paternal role, as in the comment quoted, echoes this gesture when he awakens just before E.T.’s death.) Keys, now revealed as humane (the first close-up, minutes earlier, lit his face ominously from below), confides he once resembled Elliott and has dreamed of extra-terrestrials since childhood. Keys’ visor reflects Elliott, merging them in one image, counterpart to E.T.’s earlier mirroring of Elliott’s movements. Thus cyclical continuity overlays identity between Elliott and the creature, suggesting Keys can inherit E.T.’s role, freeing the latter to return to his ‘family’. Keys accompanies Elliott’s mother in the finale, completing the circle of children and pet dog. Meanwhile, the alien has escaped without serious conflict – agents pull guns (digitally transformed into radios in the 2002 re-release) but no violence occurs – and Elliott, having acquired a super-ego (‘I’ll be right here,’ insists E.T., pointing at Elliott’s forehead) is assimilated into the reconstituted Symbolic. The earlier scenes’ castrating father is a kindly patriarch.

Reagan’s construction of the family, American as Mom and apple pie, was mythic. (Attempts to recuperate Yuppies – another manifestation of Reaganism yet almost, by definition, opposed to the family – by reference to ‘natural’ parenting impulses towards E.T., emphasises the myth’s flexibility and pervasiveness.) By the 1980s, a child living with both biological parents in their first marriage was exceptional. Narrative, however, generally seeks to restore the world to how a culture would like it to be rather than how it necessarily is. To blame the fantasy, typically unconscious, for complicity with party politics is misplaced, however. Concern should focus on grown-up leaders peddling fantasies as policy.

Self-reflexivity versus identification

At least the cinematic fantasy respects its recipients sufficiently not to expect them to take it seriously. From the opening – featuring a Wizard of Oz talking tree among the collected specimens – to the final shot of E.T. silhouetted within a closing circular portal like an iris shot ending a cartoon, accompanied by projector-like whirring, the film foregrounds fictionality. This facilitates the Imaginary/Symbolic alternation which informs the pleasure in Spielberg films. For the fantasy to satisfy requires belief that cycling children can fly across the moon. Yet nobody is ‘taken in’ (Metz 1975: 70), not even children. Here I disagree with Kolker who insists that Spielberg’s ‘self-conscious gestures’ are ‘never distancing’ (1988: 272). Using the term ‘manipulative’ and its synonyms with obsessive frequency, Kolker presents a passive subject position(ing) – unshared, significantly, by him – as the only one available, which audiences have no choice in occupying.

E.T. as fantasy is emphasised by mother reading Peter Pan to Gertie (Drew Barrymore); we hear that Tinker Bell ‘would get well again if children believed in fairies’ – redundant, unmotivated, but also virtually unnoticeable detail if the film really demanded unconditional subjection. Likewise, E.T.’s resurrection, though logically occasioned by the spaceship’s return, appears contingent upon Elliott’s and our belief. Yet eventually the part of the psyche engaged in the Imaginary is conflicted, between desire for E.T. to remain and for his reunion with his ‘family’. This contradiction, together with simultaneous belief and disbelief, helps elicit the oft-cited emotional responses to the film; irresolvable oppositions provoke laughter or tears, sometimes difficult to distinguish.

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial – ‘That’s All, Folks!’: the closing iris shot

The spacecraft’s climactic reappearance, emanating light shafts and a ‘solar wind’ that ruffles hair and clothing of characters looking up, awe-struck and expectant – stand-ins for absent spectators, elsewhere, in movie theatres – symbolises the cinematic apparatus. As spectacle it engages the scopic drive, and as narrative function promises imminent closure. But other satisfactions require detachment. A serrated grill causes the spaceship to resemble the shark from Jaws – a self-referential indulgence that flatters Spielberg fans who notice it, and rewards close, active reading. Spherical, lit through portals that form a face, the spaceship is also a jack-o’-lantern, in accordance with the Halloween setting. (In Close Encounters Jillian describes mistaken helicopter lights in a similarly staged spectacle as ‘Halloween for grown ups’.) This in turn constitutes a further allusion, to the Peanuts newspaper strip which, like E.T., represents children’s experience, with adults relegated to speech bubbles originating out of frame: specifically, every Halloween one character awaits ‘The Great Pumpkin in the Sky’.

Central to E.T.’s popularity is not merely openness to multiple readings – true of any text – but differential audience address: to adults and children, cineastes and casual moviegoers. Narrative and spectacle provide armatures for various experiences exceeding any individual’s interpretive competence. Consequently, as Umberto Eco (1987) points out, any but the most naïve response is a cult reading. The film addresses me and others ‘in the know’, as I recognise Fantasia when the scientists chase through the woods with flashlights, or as I revel in E.T.’s misrecognition of a trick-or-treat costume representing Yoda, a fellow Rambaldi creation, from The Empire Strikes Back (1980). Yet this awareness implies discourses I may be overlooking, threatening my mastery, and so encouraging further attention which, in turn, intensifies potential Imaginary identification and recognition of signs as Symbolic.

Constant repositioning occurs against the security of conventional narrative – an important difference between Spielberg’s and less mainstream texts that, similarly disrupting spectatorship, are lauded as progressive (Stam 1985). Repositioning occurs also within the narrative. The E(lliot)T identity, whereby one becomes drunk as the other drinks, or acts out fantasies the other observes on television, figures the spectator’s Imaginary relationship to the Other on-screen. Spectators are encouraged to identify with Elliott in his telempathic identification with E.T., partly because the viewpoint offered parallels E.T.’s as much as because E.T. is experienced through Elliott’s focalisation. Optical point-of-view shots align with E.T. even before Elliott encounters him. We share E.T.’s vision as he leaves the house under a sheet. Elliott’s descriptions of Earth (‘This is a peanut: we put money in it’) amuse precisely because we view our culture as an alien might. In a self-conscious ‘mis-en-abime [sic] structure – while the mother reads the “clap your hands if you believe” passage to her daughter, the son and E.T. sit transfixed in the dark, listening unobserved in the closet just as the theatre full of parents and children listen unobserved in the dark’ (Collins 1993: 260).

So far as spectators accept proffered identification, they suffer three abandonments (Harwood 1995: 153): when E.T. separates from Elliott (who falls asleep) in the forest, when he parts from Elliott by dying, and when he leaves at the end. Counterpointing each loss, necessary for Elliott’s resignation to, and acceptance into, the Symbolic, is spectatorial awareness of transtextuality or obvious artifice such as the final rainbow in the sky (a ‘boundary ritual’, marking transition between states (Fiske & Hartley 1978: 166–9)). Unlike Neary, absorbed into his (cinematic) Imaginary, Elliott remains, alone in the shot, tears running down his cheeks like many in the audience, looking up at something which, declaring itself as Symbolic, is unreal, unattainable, exactly while the spectator too breaks from primary identification with the film. The adults’ unmasking minutes earlier recalls masquerades that in many cultures ritualise passage from childhood into Symbolic knowledge (Metz 1975: 71) – fear of the mask resides in belief in its magic, which turns out to conceal benignly-presented patriarchy.

Harwood parallels the withholding of shots of E.T. (in the narrative image and early in the film) with the concealment of the nature of adult men, which results in both becoming objects of spectatorial desire (1995: 157–8). This reinforces patriarchy further to the film’s marginalisation of female characters. Elliott’s mother’s authority, the Imaginary that must be outgrown, is repeatedly undermined. Gertie – who teaches E.T. to speak, suggests ‘he’ might be female, and repeatedly sees the truth of situations that her brothers deny – is equally ‘ignored or derided’ (1995: 156).

The narrative of E.T.

Intriguing connections therefore exist between E.T.’s representation of adults, guising practised at Halloween, and so-called ‘primitive’ belief systems. Examining E.T. in relation to some models of narrative, all of which involve negotiation of loss, offers further clues to its popularity.

Halloween relates to narrative’s origins and function. A pagan ritual appropriated by Christianity, it was when evil had free reign. That this preceded All Saint’s Day (All Hallows), one of the holiest in the Church calendar, was uncoincidental. The juxtaposition represented good triumphing over evil, light over dark: a basic narrative. Although literal belief in spirits declined, their symbolisation by disguises continues playfully. Nor is the season arbitrary. Winter’s onset, heightening risks of starvation, cold, disease or attack, provoked fear and uncertainty. Halloween, then, gives vent to anxieties on a bigger scale: victorious light promises renewal next spring, sustaining hope, just as the fort-da game in Freud’s account empowered the child to master separation.

Narratives function analogously, confronting substitutes for individual and communal anxieties and desires. ‘Nowhere is nor has been a people without narrative … Narrative is international, transhistorical, transcultural: it is simply there, like life itself’ (Barthes 1975a: 79). This universality leads anthropologists as well as literary theorists to explore its function and workings. A recurrent finding is that narratives, despite surface differences, share similar structures. Linguistics shows how potentially infinite verbal utterances follow regular patterns internalised unknowingly; similarly, narratives follow underlying rules.

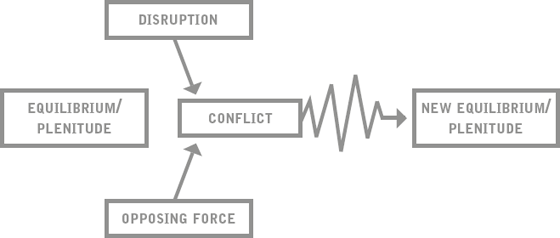

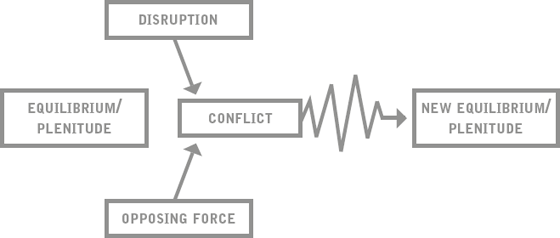

Tzvetan Todorov (1977) proposes a simple model. Narratives begin with equilibrium or plenitude. This is disrupted. An opposing force emerges to counter the disruption. Resultant conflict, precondition for any drama, is followed by triumph of either the disruptive or the opposing force, inaugurating new equilibrium or plenitude. The end differs from the start – the process is linear, not circular – but pleasure depends on closure to restore the fictional world to acceptable normality. Episodes in which first one then the other force dominates typically extend conflict, increasing involvement by means of suspense and exploring themes or testing character. The model is representable diagrammatically:

E.T.’s equilibrium (fig. 1) is the forest harmony; disruption the scientists’ arrival, forcing the spaceship’s departure, leaving E.T. stranded. Lack replaces plenitude – E.T. loses the support and security of companionship and has no means of contacting his fellow voyagers. (All conventional narratives are driven by lack, often symbolised as a lost object: the Princess in fairy tales, self-confidence in deodorant commercials, Guy’s lighter in Strangers on a Train (1951), the Lost Ark, Private Ryan, the Lost Boys in Hook, John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), The Lost World: Jurassic Park.) E.T., aided by Elliott and friends, is the opposing force working for self-preservation and to restore communication. These needs create conflict with adults, represented by the scientists, committed to capturing and, Elliott believes, destroying the alien. Eventually, new equilibrium and plenitude occur as E.T. returns home. Simultaneously, Elliott’s narrative has been disrupted by his father’s departure – representing an untrustworthy adult world – so that E.T., fulfilling that role, becomes the opposing force that keeps Elliott in conflict with patriarchy until reconciliation with Keys compensates for the lack.

Fig. 1: Todorov’s narrative model

As that second application of the model indicates, story does not necessarily coincide with plot, the story’s presentation in a text: Elliott’s father leaves before the film begins. Story is the chronological, cause-and-effect order of events, whereas plot often respects neither causality nor chronology and omits events for dramatic purposes, such as enigma and suspense. Plot (syuzhet) can therefore be conceptualised as the textual ordering of events, the narrative signifier, while story (fabula) is a mental construct, the signified. Models of narrative structure apply most readily to story.

Mythology

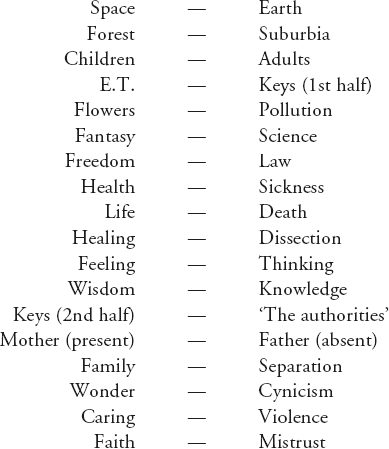

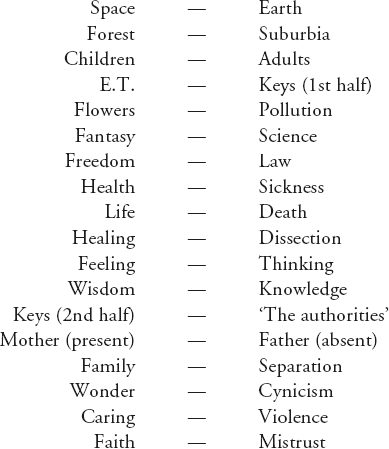

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1955; 1966) examines ancient and contemporary myths and legends from cultures worldwide to investigate how narratives mediate reality. He concludes that narratives structure meaning as the human mind does: in binary oppositions. These are an immensely powerful system of describing and defining experience in relation to the user. That any disturbance to the system is either an abomination or fantastic illustrates their importance in maintaining mastery. Consider horror films: Frankenstein’s monster is alive yet made from corpses, sensitive yet brutally strong, human yet a technological product; Dracula is neither alive nor dead, both human and animal. Horror is associated with the full moon, a phenomenon that elides polarities between day and night, light and dark, by transposing expected qualities. More controversially, women in films who challenge the binary structure man-senior-active-sexual versus woman-younger-passive-virginal, such as Alex in Fatal Attraction (1987), the femme fatale in film noir, or Thelma and Louise, are aberrations the narrative must destroy. Narrative is conservative.

Lévi-Strauss concludes that the overarching opposition is nature versus culture. In the above chart, qualities on the left are broadly aligned with nature, those on the right with culture. Furthermore, in this text nature is positive and culture negative, although this is not always so.

Binary oppositions split the world. Narrative, seeking Imaginary unity, heals the rift that remains open in actual experience. Horror and science fiction, conversely, often reassert distinctions that have blurred: vampires and zombies require expulsion from the realm of the living; Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs monstrously combine nature and technology, an affront resolved when nature evolves to re-establish conflict between those principles. Heroes, who often straddle nature and culture, accordingly eliminate or restore oppositions. Indiana Jones uses academic learning combined with survival instincts: intellect alongside physicality. Oskar Schindler recognises common humanity (nature) to overcome his alliance to Nazism (depraved culture) and exploits familiarity with the world of debased appetites (nature) to assert more civilised values of responsibility (culture) towards ‘his’ Jews. Both Keys, in switching sides, and E.T., who uses technology to build his transmitter, cross the divide – as does Elliott, in psychoanalytic terms moving from the Imaginary (nature) to the Symbolic (culture).

Fig. 2: Binary oppositions in E.T.

Conclusion

E.T. conforms to these and other narratological models, including Edward Branigan’s (1992) and that proposed by Vladimir Propp’s (1975) morphology of Russian folk tales (1975). That may help explain its ability to evoke widespread pleasure. Such a claim is not, however, an instance of the derogatory dismissal of Hollywood entertainment as ‘formulaic’, which implies prescribed schemes narratives conform to at the expense of integrity. E.T.’s typicality is not apparent during normal viewing, yet it links the film to unconscious processes. This alone cannot account for commercial success – after all, it stresses what E.T. shares with other narratives, rather than uniqueness (indeed narrative models ignore the specificity of how the story is told) – but in combination with factors discussed earlier it is highly significant. There is no escaping that such models presuppose a single meaning, a narrative inherent within the text, irrespective of readings constructed by spectators. Even so, recognition that verbal language is systematic and rule-governed does not preclude acceptance that it is ambiguous and polysemic; there appears no reason why analysis of audiovisual texts should not proceed under similar assumptions.

Finally, as critics immediately realised, E.T. contains striking parallels with the Gospel, observable in both mise-en-scène and narrative. Elliott (whose mother is called Mary) first encounters E.T. in a radiant outhouse which he approaches, carrying a tray like a Magus bearing a gift, by following lights ahead of him in the frame (Spielberg’s characteristic signifier of desire); these include a crescent moon that hangs overhead, recalling the Bethlehem star, as Elliott kneels before the shed. Later, representatives of the persecuting authorities wear helmets like those of Roman centurions’. E.T. arrives from the sky, suffers little children to come unto him, and performs miracles: levitation, healing, reviving dead flowers. He dies and undergoes resurrection before returning to the heavens with the reverberating message, ‘Be Good,’ having reunited the spectator’s textual surrogate with a father. He escapes from a sealed ‘tomb’ – an episode replete with rebirth symbols, such as the oval window on the storage vessel, the umbilicus to the van that breaks from the placenta-like bubble around the house, and the medical imagery mentioned earlier – then, shrouded in a white cloak, his heart glowing red, he extends two fingers in benediction. As paternal figure himself, as infant requiring nurturing and protection, and as inspirer of positive telempathic feelings that negate individual difference, he is at once Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

What to make of this is unclear. Spielberg, at that time a lapsed Jew, has never discussed in interviews whether these parallels were conscious. I do not claim that cinema fulfils functions hitherto attributed to religion – although its ritual aspects, the temple-like architecture of picture palaces, the overwhelming nature of the spectacle, stardom (whereby posters adorn walls which once might have displayed religious icons), its reinforcement of ideologies and its association with holidays present a powerful case. Nor am I reductively asserting that religion is merely another form of narrative. Nevertheless, one of the Western world’s most profitable entertainments, and the most successful religion instituted there, display remarkable similarities.

I reject the Messianic readings many ideological critics make of Spielberg’s films. Fantasies purportedly offering facile solutions are as likely to heighten dissatisfaction as to lull the masses to passive compliance with their own subjection. This is not to deny, though, that popular movies appeal to widespread psychological needs that express themselves recurrently as archetypes. Narrative models discussed above, as well as psychoanalysis, in their own terms presuppose this. Without succumbing to obfuscating mysticism, it seems reasonable to agree with Peter M. Lowentrout that E.T.’s is ‘the mythically necessary death of the too pure and incorruptible in a corrupt world’ (1988: 350). E.T.’s telempathic relationship with fellow aliens, with Elliott and with nature, and ability to perform miracles, posit a community amongst all things that radically contradicts individualism. Rather than complicity with essentialist conceptions of ‘natural’ order and identity, E.T. manifests a carnivalesque attitude with emphasis on Elliott and E.T.’s drunkenness, mistrust of authority, loss of selfhood through telepathy and disguises, E.T.’s grotesque body and his ambiguity in terms of age and gender. Carnivalesque is especially pronounced in the extended reissue, which presents Halloween trick-or-treating in disturbing imagery reminiscent of an urban riot.