A.I. Artificial Intelligence was keenly anticipated, partly because of mysterious Internet marketing (Vulliamy 2001: 20; see www.cloudmakers.org), and partly curiosity. Would it be ‘the ultimate meeting of two of cinema’s most inventive minds’ or – Spielberg’s image obtruding again – ‘sentimental travesty of Kubrick’s intentions’ (Gumbel 2001: 11)? Although Kubrick, having co-written a ninety-page treatment, asked Spielberg to direct in 1994, Spielberg penned his own screenplay from Kubrick’s notes and drawings after Kubrick died – his first since Poltergeist, and the first of his own he had directed since Close Encounters.

Accordingly, authorship dominated debate. A.I. polarised but fascinated critics. Its title inevitably provoked variants on Roger Ebert’s observation that A.I.’s ‘facile and sentimental’ conclusion ‘mastered the artificial but not the intelligence’ (2001: 6). Implicitly the former was Spielberg’s, Kubrick’s the latter. Kubrick directed surgically indifferent meditations on passivity before powerful, often humanly created, forces; Spielberg ‘benevolent science fiction as seen through the sensibilities of a child’ (Lyman 2001: 5). In fact only two Spielberg films fitted that description, which ignores misanthropic early work. A.I. continues the darker, more adult tendencies of his 1990s ‘history’ films. Unclear initially, moreover, was that in this ‘unlikely collision of Kubrick’s hardcore dystopianism and Spielberg’s gushing emotional overload’ (Roux 2001: 4), this ‘heartfelt mishmash of Pinocchio and Oedipus’ (Hoberman 2001: 16), the Pinocchio elements came not from Close Encounters’ director but Kubrick.

Adjectives like ‘frustrating’ repeatedly conveyed inconsistencies and contradictions (Brodesser 2001: 41). Pundits declared A.I. unmarketable. Spielberg, characteristically, had withheld key images and plot points, but the resultant enigma was whether it resembled E.T. or Saving Private Ryan. Some thought the movie should have been more family-friendly to attract a broader audience than its American PG-13 rating allowed. Others felt promotion over-emphasised its child star, misleading cinemagoers to expect something more comforting. Executives, including several among DreamWorks’ competitors, praised the campaign’s tenor as corresponding to the movie’s adult themes and perceived subtleties and complexities. This view corroborated a late switch to a 25-and-over arthouse-oriented market (DiOrio 2001: 9).

The hype vaguely predicted ‘Titanic-like figures’ for A.I., which Spielberg finished early, saving a third of the $120 million budget (Wolf 2001: 19). It grossed $29.4 million during its opening weekend, accumulating $42.7 million over the first six days, including Independence Day. While impressive, given the niche audience, this was less than Saving Private Ryan earned in a comparable period three years previously (DiOrio 2001), and unremarkable against the $75.1 million Pearl Harbor (2001), A.I.’s critically derided competitor, garnered during a four-day opening. This was hardly disastrous: studios banked on theatrical revenue supplying 23 per cent of domestic income (Branston 2000: 57). Nevertheless, A.I.’s relative failure compounded trade press reports of ‘violent antipathy’ from audiences, which dropped 50 per cent then 63 per cent in the second and third weeks – making it, J. Hoberman avers, not Spielberg’s first perceived dud but the first to fare better critically than commercially (2001: 16).

In fact, Farah Mendlesohn states, the profits of Star Wars, Close Encounters, E.T. and The Matrix are aberrant for science fiction – explicable, she claims, by their fairy tale qualities – whereas much good science fiction flops (2001 initially, for example): typically concerned with thought rather than action, it ‘doesn’t play well on the screen’ (2001: 20). Spielberg, conversely, centres ‘human identity … in emotional receptivity’ (Arthur 2001: 25): E.T. ‘feels’ Elliott’s feelings. Tim Kreider (2002) believes this explains division over A.I. – variously the year’s best film, or plain ludicrous. As a child protagonist’s wish-fulfilment fantasy, it is embarrassingly mawkish. As simultaneous commentary on the hollowness of such comforts, foregrounded by having a robot, built to replicate human attachments, pursue them beyond any life-span, it is darkly cerebral. Anthony Quinn, in educing, according to preconceptions, that ‘Spielberg seems to believe he’s offering something profound and uplifting’, not ‘bleak and hopeless’ (2001: 10), like many ascribes this schism to misguided direction rather than a (conscious or otherwise) structuring opposition.

Authorship

‘An Amblin/Stanley Kubrick Production’: A.I. credits itself, albeit posthumously, as collaborative. Spielberg spoke animatedly of a fax line linking the directors’ homes. The movie specifically alludes to both filmmakers’ output, considered later, and evinces thematic and stylistic continuities. A machine espousing emotions while humans behave impersonally, as if programmed, is characteristically Kubrick’s idea. A lost child is typical Spielberg. Yet qualities Paul Arthur identifies with Spielberg appear equally in 2001: ‘the mystic light show as harbinger of the Beyond (Raiders of the Lost Ark, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Always), the magical resurrection or second coming that smacks of New Testament theology (start with Jaws …)’ (2001: 25). Moreover Schindler’s List’s industrial genocide was inexorable as any of Kubrick’s machine-like institutions or conditioned characters, while Saving Private Ryan’s beach landing shows infantrymen obeying automatic instincts (one retrieves his own severed arm).

Kubrick spent 17 years on A.I. with five writers, inarguably making Brian Aldiss’s story, ‘Supertoys Last All Summer Long’, his own, having incorporated Pinocchio against Aldiss’s judgement (Argent 2001: 53). Kubrick had apparently started A.I. inspired by E.T.’s success (Hoberman 2001: 17). Jurassic Park convinced Kubrick of Spielberg’s technical ability to bring to the screen something previously unrealisable, and more quickly than he could. Having rejected building an automaton for the lead role, Kubrick acknowledged that his painstaking methods meant a boy actor would age during production. Spielberg, recognised for directing children, and a long-standing admirer and friend, was an obvious choice: especially as, unlike ‘Supertoys’, Kubrick envisaged Pinocchio – as writer Sara Maitland insists he called the project – as ‘sentimental, dreamlike’ (Argent 2001: 51).

Self-reflexivity

The dissolve from the initial contextualising shot of high waves to the silhouetted Cybertronics Corp. statue outside a rain-streaked window immediately inscribes a screen, separating the spectator from an enigmatic figure that later becomes David’s (Haley Joel Osment) object of desire. The metaphor consolidates as the camera pulls back to frame Professor Hobby (William Hurt) in close-up, against darkness; it redoubles as a track along the back of a lecture theatre follows him, inscribed spectators silhouetted in the foreground. Pillars and railings constitute internal frames. A beam reflected behind Hobby shines directly into camera as intra- and extra-diegetic audiences concentrate on his vision.

Dichotomised realism (‘authenticity’) and illusion – that polarisation between Spielberg’s critics, traceable to the Lumières and Méliès – returns in the guise of artificial intelligence versus humanity. When Hobby stabs the hand of a robot, played – like the equally fictitious human characters – by a human performer, she screams as if real, but when he asks what he did to her feelings she insists he hurt her hand. As in film acting, the manifestation is superficial, emotion inferred. With light projecting from behind her head in Spielberg’s signature image of desire, she defines love as replicable ‘sensuality simulations’. Hobby directs her, ordering her to undress, then stopping her – here exploiting spectatorial voyeurism and pruriently testing suspension of disbelief (surely a human body will emerge from this shapely figure?). Fetishisation of the female and of CGI effects that foreground cinematic artifice coincide as he pauses to expose the inner workings of her head. She sheds a tear, implying conscious humiliation behind her programmed complicity; equally – a fundamental ambiguity – that such symptoms are merely physiological. A.I. concludes after an analogous, book-ending shot of David crying over his resurrected surrogate mother (Koresky 2003); at that point in a Spielberg movie when the scene apparently solicits empathy (for many it failed), whether David’s emotion is authentic is crucial. Responses depend on how convincingly the text portrays feelings viewers can share. ‘The mecha quest for an impossible authenticity [that] becomes the movie’s driving mechanism’ (Hoberman 2001: 17) culminates in David achieving ‘idealised emotional harmony we humans unconsciously crave but can never fully realise in our adult lives’ (Arthur 2001: 22). This is the Imaginary, narrative’s ‘lost’ object, substituted also in primary identification with a film.

Hobby’s project for ‘a perfect child caught in a freeze-frame’ renders cinematic parallels explicit. David, facsimile of a real deceased boy, eventually lives on, fixed, unchanging, constituting documentary evidence for future ‘super-mechas’. Recall the Lumières’ review that predicted cinematography would summon deceased loved ones, or debates around Schindler’s List as ‘witnessing’. David’s survival into an ice age literalises ‘freeze-frame’, trapping him, latent, static, as if sealed in a can awaiting projection. The toppled Ferris wheel enclosing his suspended quest aptly visualises ‘the final reel’.

Sheila, Hobby’s demonstration robot, applies make-up literally to repair her face before a fade to black. After a caption, ‘20 MONTHS LATER’, Monica (Frances O’Connor) and Henry (Sam Robards), the couple who adopt David, are driving to the facility where their incurably ill son is frozen. Correspondence between Martin’s (Jake Thomas) suspended animation and David’s future parallels humans with robots – ‘orgas’ with ‘mechas’, as characters term themselves – implying both are human variants. So does the first shot of Monica, also applying cosmetics using a compact mirror. Self-presentation and appearance anticipate the common human need for recognition underlying David’s obsession with reciprocity of his filial love.

Implied narcissism raises awkward issues in relation to Hobby replicating his dead son and Monica adopting, then abandoning, David. Do children exist, like servile robots, merely to satisfy parents (Hoberman 2001)? The mirrors furthermore inaugurate an image system of reflections, central to David’s determination to escape Symbolic positioning as a mecha and merge into Imaginary unity with Monica. This involves cinematic metaphors as light flashes down on the car, reflections in its glass inscribing a screen between us and the occupants. In the clinic shafts illuminate their object of desire, the pod containing Martin.

On David’s arrival home, the door opens on the overexposed exterior as on to a blank screen from which he enters, elongated by an unfocused lens. Like the Close Encounters aliens, he appears – as a film character is – born of light. The image recalls that David is Spielberg’s progeny and recollects his diegetic ‘father’ as it resembles the Cybertronics statue. It also anticipates the super-mechas, evolved avatars of his artificial human intelligence. Henry has orchestrated the moment to normalise domesticity in the absence of ‘digested’ grief, as a doctor says, because Martin is not dead but ‘pending’. Henry thereby reclaims paternity. His possible selfishness, or at least renewed identity, figures in his reflection in an illuminated-surround mirror, watching the scene.

Monica initially rejects David, partly for being too real. His reflections appear in family photos and finally on Martin’s portrait. Focalisation through Monica and Henry, staring from behind a doorjamb, suggests unease about replacing their son, rather than that these signify David’s Mirror Phase; he remains an expressionless puppet until activated to love. Fractured reflections in multiple mirrors express parental uncertainties as Henry explains the irrevocable imprinting procedure. A tinkling chrome mobile reflects David; it portrays two children and a mother with a space where her heart should be. At bedtime David follows Monica towards a ribbed glass door – through it his image splits, as if on a screen that reveals, yet imposes a barrier to, her potential object of desire. Distressed, she looks from the shadows, curious, as Henry dresses David, whose image partially resolves as he advances, meets her gaze, and smiles.

Cut to the following morning: Monica is reflected in a shiny lid, one of many circles framing her and later David with her. As David, a curious toddler with a ten-year-old’s body and vocabulary, intently watches her pour coffee, the top of his face comically reflects in the table surface, rendering him for the spectator as a four-eyed alien, underlining radical otherness. Birdsong and piano melodies, resolving from discordant music-box tinkles, increasingly suggest calm and normality – despite Monica’s awkwardness, the clinical décor, the predominantly cold, blue hues, David’s unsettling tendency to materialise unexpectedly, and his unblinking stare. (As in Empire of the Sun, the piano repeatedly signifies maternal bliss.) Monica, making the bed, lifts a sheet; David is there when it falls, as if projected on the blank plane. Monica’s overalls resemble the utilitarian suit David arrived in, implying affinity, a Mirror Phase in which proto-mother and -son are yet to recognise mutual definition. When, rattled by his presence, she puts him in a glass-door cupboard, the light dims as he freezes, as though projection stops.

Psychoanalysis appears perversely redundant in a movie in which the boy opens the toilet door on Monica as she sits, underwear around her ankles, reading Freud on Women. Nevertheless, overlaying David’s knowingly Oedipal narrative is less emphatic re-inscription of spectator/text relations as understood in Lacanian terms. In this scene, for example, as David stares at Monica, the camera frames her in the doorway, subjected to our gaze also. At dinner, David, aspiring to his programmed familial role but unable as a mecha to eat, imitates the adults, using empty utensils. He thus sees them as mirroring his incipient identity but seeks also to join them, to occupy the space suggested by the empty chair in the foreground.

Reciprocally, when David laughs at spaghetti hanging from Monica’s lip, his manic outburst startles both parents, and viewers; relieved, they (and we) relax and share his mirth – empathy with a mechanical projection, substitute for a real human relationship (in effect ourselves taking the unused seat) – until awkwardness encroaches as David laughs too long, then halts abruptly. Far from unalloyed manipulation constantly charged against Spielberg, this supremely self-reflexive moment, Kreider observes, demonstrates, ‘with a directorial flourish, how easily our emotions are coached’, leaving us ‘just imitating the expressions in front of us, laughing and crying at nothing, going through the motions’ (2003: 33). Following its chilling account of ‘sensuality simulations’, the movie is as aware of, and interested in, the artificiality of its intelligence and emotions as the most disapproving Frankfurt theorist. From Hobby’s seeming cruelty to the Holocaust imagery of dumped mecha parts, from Joe’s chivalry towards an abused woman to Martin’s mobility by means of techno-trousers, repeatedly it juxtaposes, and blurs boundaries between, humans and automata, within a reflexively cinematic metadiscourse. David’s artificial imprinting and subsequent rejection motivate him with the unattainable desire for a lost object that impels the movie’s audience into the cinema. As Kreider notes,

Every character in the film seems as pre-programmed as David, obsessed with the image of a lost loved one, and tries to replace that person with a technological simulacrum. Dr Hobby designed David as an exact duplicate of his own dead child …; Monica used him as a substitute for her comatose son; and, completing the sad cycle two thousand years later, David comforts himself with a cloned copy of Monica. (2003: 34)

The oval canopy of Martin’s bed in which David simulates sleep, shot from end on, resembles a self-enclosed orb containing David and Monica, visually correlating to his Imaginary. Its blue illumination institutes David’s obsession with the Blue Fairy, his quest object. Cutaways to Martin, similarly bathed in cold light and haloed in his cryogenic capsule, are Monica’s subjective visions before she decides to imprint David with undying love. Taking the code from a warm red folder, she reaches out to hold him and speak the requisite words as both appear in a two-shot against radiating intense white light. This moment, in which David’s relaxation seemingly transforms him into a human and is marked by transition from calling her ‘Monica’ to ‘Mummy’, explicitly equates cinematic projection with the Imaginary.

After a fade to black, David’s point-of-view shot resembles a TV commercial as Henry and Monica in evening dress prepare for an outing. It frames Monica doubly within the mise-en scène; receding doorways reinforce its voyeuristic nature, emphasising David’s desire as the parents argue good-naturedly over whether he is a child or toy. After she implicitly forgives him for wasting rare perfume, David, with light behind him as if projecting his concerns, asks fearfully when she will die. While a mirror shows her reactions – she is learning identification with her new role, but the circular frame also relates it to David’s Imaginary – the camera cranes to look down her cleavage, as if acknowledging sexual undercurrents Martin’s imminent recovery will activate.

The rape of the lock

David’s perfection highlights Martin’s flawed humanity. He refuses to break toys, despite Martin’s urging, and helps mummy in the kitchen to prepare Martin’s medication. Warm colours now suffuse the household, the characters and décor carefully coordinated. Martin chooses Pinocchio for Monica to read them, maliciously proclaiming ‘David is going to love it’ – the story of a puppet that yearns to become real. David listens enraptured in the corner at bedtime, silhouetted like a film spectator against a rosy glow, craning forward while Monica and Martin occupy the blue oval enclosure. The Blue Fairy (described in the book as ‘my kind mother’ (Collodi 1988: 140)) appears in Pinocchio’s dream, kissing him after he undertakes chores on her behalf. As David stares, in calm, unspoken longing, an aquarium behind him foreshadows his fate, just as concentric shapes enclosing the bed pre-echo the whale’s belly in the Pinocchio fairground ride.

Sibling rivalry climaxes when David, emulating Martin, clogs his circuits with spinach. Martin glowers at Monica, reflected, holding David’s hand during the remedial operation. A sound bridge links this to Martin setting a ‘special mission’ he claims will make mummy love David. A ‘projection beam’ behind Martin unbalances a symmetrical two-shot in which the boys mirror each other in front of a mother-and-child picture: each envies the other’s ego-ideal status. Castration symbolism permeates Martin’s plan for David to ‘sneak into mummy’s bedroom’ and shear a lock of hair, as well as Oedipal challenge to Henry – as the father later confirms, responding to Monica’s reasoned reaction by calling David’s scissors ‘a knife’. On Martin’s birthday, although David brings a present and Martin even defends him against bigger boys, phallic rivalry precipitates the crisis prompting David’s banishment. Unable to discern difference between David and themselves, the boys ask whether he can pee. This ‘lack’ – robots do not pee – marks the difference between orga and mecha and their unequal treatment in the Symbolic order: exactly analogous to the Real of sexual difference.

When Martin’s friend stabs David to test him – echoing Hobby’s treatment of Sheila – David panics and clings to his orga brother, accidentally dragging him into the pool. After David’s density sinks them, he remains, limbs outstretched in an empty embrace following Martin’s rescue. This prefiguring of his future includes an optical point-of-view of mother, family, humanity: distanced, unreachable, beyond the meniscus before an overhead shot retreats to frame him in a blue, screen-shaped rectangle.

The next scene rhymes by presenting Monica, against a blue background, overlaid by reflections in a glass screen: separated from the son she chose to love when she returned to hold his hand after initial revulsion at his artificiality. A blue, circular window frames her, but excludes David; when it frames him, she remains outside it. David’s crayoned letters to her express contrary feelings; his controlled demeanour belies desperation to define their relationship in words pleasing to her. His multi-coloured, if mechanical, writing is a visual residue of their short relationship; everything again now appears cold and superficial. One letter parallels orga binary logic in fantasising a Symbolic order whereby Mummy, Martin and David are real, but Teddy – Martin’s mecha toy, given to David before Martin’s remission – is not. Tearful and conflicted, repeatedly looking back at Henry but avoiding eye contact with David, Monica betrays him by lying: ‘Tomorrow’s gonna be just for us.’ Continuing from David in the pool, this scene further shifts focalisation towards David as Monica now behaves artificially.

As in the previous drive in the country, the car’s bubble is a reflexive screen, repeatedly whiting out as David seeks reconciliation with Monica, whose tears confirm discomfort about editing him from her movie. Robotic in determination, Monica nevertheless bypasses the Cybertronics plant where she is supposedly taking David for destruction. Instead she drives into a dazzling light shaft, a projector beam for David’s Imaginary and her fantasy of giving him a chance. Abandoning him in the woods, she last sees him diminishing in a wing mirror, another oval framing, as he cries after her, centred in a cone of flickering beams.

That’s entertainment

Similar imagery links this scene of childhood innocence to the following urban scenario. Although Monica’s last words are, ‘I’m sorry I didn’t tell you about the world’, ensuing conflicts differ only in degree, not nature or motivation, from David’s domestic experiences. During the transitional fade to black, a voice articulates what David is feeling: ‘I’m afraid.’ It is a woman’s, whose bruises indicate an abusive orga partner; she is seeking solace from lover mecha Gigolo Joe (Jude Law), much as David briefly satisfied Monica’s maternal needs. A surrogate for real, but flawed, human relationships, Joe personifies the diversionary aspects of popular entertainment. He embodies cinematic history, melting hearts with songs from 1930s musicals and dancing in puddles (specifically a reference to Singin’ in the Rain, but also Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), which, we shall see, informs many of A.I.’s deepest concerns). His first song, ‘I Only Have Eyes For You’, immediately alludes to scopic desire and power at the heart of A.I. Moreover, he incarnates the cinematic apparatus. Changing appearance to suit his next client’s fantasy, like a film star, he checks himself – both projecting and assuming his introjected role – in a mirror (metaphorical screen), built into his hand which doubles simultaneously as a lamp. Later, to tempt teenage boys to drive him and David to Rouge City, he projects a hologram.

An orga frames Joe for murder. David also is scapegoated for orga dissatisfaction and jealousies. While Joe seeks to escape the Symbolic by excising his operating licence, his identity, a sound bridge to David in the woods, telling Teddy, ‘If I am a real boy I can go back and she’ll love me’, highlights the parallel. Self-reflexivity again underlines vision as David experiences unforeseen dangers. A refuse truck arrives, preceded by spotlight beams. One shot isolates David’s eyes behind dumped objects in close-up before damaged redundant mechas emerge from the dazzling background to pick over body parts like a cannibal zombie horror movie. Yet they demonstrate – unlike humans – unqualified mutual cooperation in repairing themselves. One replaces an eyeball. This powerfully draws attention to his look, as indirect narration relays the spectator’s scopic drive through further characters’ reactions to an unseen stimulus. Another stares off-screen, upwards towards illumination, hollering, ‘Moon on the rise!’ as the camera tracks in on his face. Then David looks over his shoulder, before a cut to an impossibly enormous full moon. A further shot of a welder raising his mask further emphasises the spectacle (against realist logic: robot welders hardly need eye protection), then a female mecha looking up: no fewer than six inscribed looks, as Joe, on the margin of the scene, observes the brightening sky.

The moon, however, is a gigantic balloon that compounds nature and technology, beauty and danger, spectacle and observer. From the basket, sprouting cameras, movie spotlights project beams that return the characters’ and the spectator’s searching gaze. As Christian Metz puts it, ‘the spectator is the searchlight … duplicating the projector, which itself duplicates the camera, and he [sic] is also the sensitive surface duplicating the screen, which itself duplicates the film strip’ (1975: 53). The basket seats an inscribed director, surrounded by screens, using a megaphone to control capturing of replicated human forms for entertainment. The Flesh Fair he supplies parodies Hollywood, not least DreamWorks’ recent success, Gladiator (2000). It is crowd-pleasing, American (US flags abound), spectacular. Rock ’n’ roll, circus, mechanical destruction, violence, big screens and light shafts exploit and express social fears – here, of artificiality, as he invites people, ‘Expel your mechas,’ while the compère asserts, ‘We are alive and this is a celebration of life.’

Motorcyclists pursue the mechas, effectively capturing them in their headlights. Foreground objects in parallel tracking shots impose a flickering reminiscent of silent film chases, the original action movies. A mecha, who in darkness looks normal, but has no head behind her face – two-dimensional, like a projection – stands before shafts of light reciprocal to David’s searching gaze as she offers to nanny him. Light plays over David as if from a screen as he asks whether she knows the Blue Fairy. Before she can answer, the entire opposite wall collapses, leaving a bright rectangle penetrated by ferocious-looking pursuers: the recurrent Spielberg nightmare of the screen, plane of the Symbolic, as permeable barrier against the horror of the Real, counterpart to the fantasy of the screen as access to a desired Imaginary.

Another metaphorical screen incarcerates the Flesh Fair mechas, providing protection as well as vision. Orgas discharge a mecha from a cannon. His flaming, severed head, still animated, flies towards the mechas (and us) before jamming between, and sliding down, cage bars. The huge propeller through which he is fired imposes a projector sound, and blasts the unwilling captive audience with a solar wind. The control room, full of screens, where the showman’s daughter takes Teddy after he claims David is human, resembles an editing suite. David, frightened and confused, as a child watching A.I. at this point might be, clasps Joe’s hand. (Importantly, the images are less horrific for adults because the mechas destroyed are evidently machines.) The cage, dividing mechas from orgas, inscribes a metaphorical surface between David and his desire to join the humans; the parallel with spectatorial identification compounds when the girl, looking at David, recognises humanity in his eyes. David’s escape from the arena with Joe traverses a rectangle of white light.

Rouge City too is a commercial fantasy, resembling cinema. David and Joe ascend an escalator, as in a multiplex, before passing through a whiteout to emerge among holograms and projection beams. The neon church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Heart, contrasting with the mobile that signifies Monica’s heartlessness, explicitly equates the Blue Fairy to the Virgin, appropriately for this boy of no woman born. Such idealisation of motherhood resonates with the lost Imaginary and desire for identification exploited by cinematic suture, both paralleled by David’s quest. The ‘Dr Know’ attraction, a kind of super search-engine, furthermore elevates cinema’s claims to truth as it comprises a mini projection theatre in which curtains open upon a screen; its entrance is a dark blue passage with illuminated sprocket holes or screens, typical multiplex décor. Cinema once more is apotheosised, as David, in another Persona re-run, tries to grasp a Blue Fairy hologram and, failing, attempts to enter the screen. Finally, though, as David asserts his conviction that fairy tales are real – a self-reflexive statement permitting speculation on A.I.’s own pretension to serious art – the answer to his enquiry, about how the Blue Fairy could make a robot real, scrolls up the screen. (Based on Yeats’s poem, ‘The Stolen Child’, it confirms the movie’s high-cultural aspirations.) This projection – drawn lines radiate from the text – points David to ‘where dreams are born’. Although, diegetically, the conundrum refers to Manhattan, such a description applies equally to Hollywood. By a tenuous metonymic chain, the Coney Island funfair where David finds the Blue Fairy reflects the one at Santa Monica (Hollywood’s nearest resort, where the Ferris wheel rolls into the sea in 1941), a name neatly compounding ‘Our Lady’ and David’s ‘mummy’.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence – the inscribed apparatus: David’s endless quest for the lost mother

On the windscreen of the amphibicopter in which David, Joe and Teddy depart, a computer graphic of Manhattan, visible both inside and out, projects their desire until the real thing coincides exactly. Droplets on the screen and dazzling white cascades create a spectacular light show, superimposed over their enthralled expressions, as they near their destination, a skyscraper entered through a whited-out rectangular aperture. Light shafts lure them through semi-translucent doors. Nursery chimes play and light radiates from behind David as he penetrates the Imaginary of his lost origins, the primal scene of Professor Hobby’s office. The ensuing Mirror Phase, however, instead of regressing him to merge with his like, confronts him with the horror of the Real. ‘Is this the place they make you real?’ he asks, enchanted. A chair revolves, in a shot modelled on Mother’s revelation as mummy in Psycho, only this time it is another self he meets, this robot who thinks he is unique. ‘This is the place they make you read’, his Other responds, shattering David’s identity with a minuscule arbitrary difference in the Symbolic register. After innocently enquiring, ‘Are you me?’ David reacts, in this over-exposed theatre of light, by insisting, ‘She’s mine! And I’m the only one!’ and smashes and decapitates his counterpart with a lamp, proclaiming uniqueness at the moment he demonstrates humanity’s tragic failing. The scene shocks in direct ratio to the extent one accepts him and his emotions as real.

After Hobby intervenes, appropriating for himself the Blue Fairy role, and David repudiates him, David becomes Hobby’s object of desire: lost surrogate for his deceased son. Bright lights in the dark background link Hobby’s projective gaze to David across the frame. Hobby departs to summon his team, the camera positioned behind doors that slide open to convert yet another vertical plane into an aperture. David sits gazing into it like a spectator. Inquisitive, he follows lights, like Elliott encountering E.T., into the space, indeed, of his conception: past a flat monitor displaying the Cybertronics logo – mise-en-abyme of the movie’s second shot – and photographs of the original David. He encounters multiple copies of himself, like sequential images on film, awaiting animation; a trope literalised when one of the packaged goods, apparently backlit in their boxes, moves. His moment of clarity juxtaposes an optician’s chart and instruments before the window and statue. The camera tracks towards a seated figure facing the metaphorical screen showing the symbol of David’s true origins. Horror figures again, the shot repeating Psycho’s revelation that mother is ‘not quite herself’. Instead of personality and affirmation, it presents inanimate matter in the guise of life, radically undermining identity. David looks through the eye sockets of his own death mask. Hobby, cloning mechas to deny his son’s death, equates to Norman stuffing birds and keeping Mother’s preserved corpse alive in fantasy. The tears at the start and end of A.I. recall the single tear shed in Psycho, when Marion is bereft of identity by another’s projective vision.

David’s red collar and his flesh tones now provide the only warmth among dull greys in a supposedly human environment. Wind currents but no accompanying light (Spielberg’s metaphor for hope or desire) buffet David, perched alongside the statue, a Phoenix-like vision when he drew it for Martin, now a vainglorious shell. His last word, ‘Mummy’, is a lament rather than an appeal. With no reason to live (created solely to love), he throws himself into the sea, his plummet, reflected in the amphibicopter windscreen, superimposed over Joe’s face. Here one of the movie’s few moments of compassion reveals itself in a robot, just as mechas provided comfort and deactivated each others’ pain receptors at the Flesh Fair. Immersed now in intense blue – metonym for motherhood – a dazzling beam appears behind David, projecting onto something off-screen, towards which, reanimated, he stretches: a recurrence of Persona’s keynote image. The moment he reaches to embrace the chimera, subsequently revealed as a fairground effigy, of the Blue Fairy, a real – yet appropriately artificial and mechanical – embrace clasps him: a grappling device operated by Joe, who rescues him.

Hyper-excited, like Jim seeing the American fighter at the structurally parallel point in Empire of the Sun, David completes his quest alone following Joe’s arrest. Beams from the amphibicopter penetrate the depths, inscribing his gaze. As he approaches Gepetto’s workshop, through a rectangular gateway, a reverse-shot from behind the scene of Pinocchio’s manufacture presents illusory animation in the moving light. Similarly, seaweed waving in the current appears to animate the Blue Fairy’s hair, her idealisation emphasised by consequent resemblance to Botticelli’s Venus. (Longstanding associations link motherhood with the sea – both, analogously, sources of life; compare such disparate texts that combine childhood wonder and horror as Kingsley’s The Water-Babies and Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) (Morris 1990).) Overlapping edits slow and intensify David’s fetishised vision, which appears superimposed, reflected in the amphibicopter’s bubble. The static image fixes eternally in his gaze. Yet, enclosed in the framework of a bower, it evokes also the archetypal spider woman, the femme fatale, projection of male anxieties, reciprocally trapping him. Illuminated panels behind his head echo the headlamps, suggesting a projection room. The projector, Metz writes, is ‘an apparatus the spectator has behind him [sic], at the back of his head, that is, precisely where fantasy locates the “focus” of all vision’ (1975: 52; a footnote translates ‘derrière la tête’ as ‘at the back of one’s mind’ as well as ‘behind one’s head’). Her reflection merges with David, the long-awaited regression to the Mirror Phase, to effect Imaginary reunion.

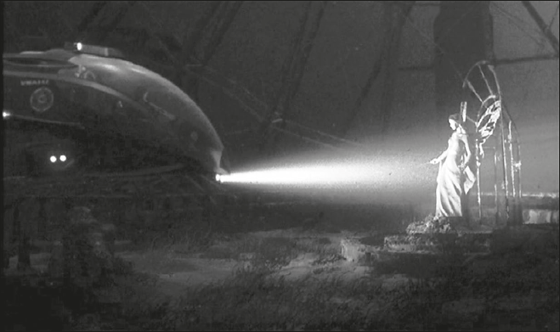

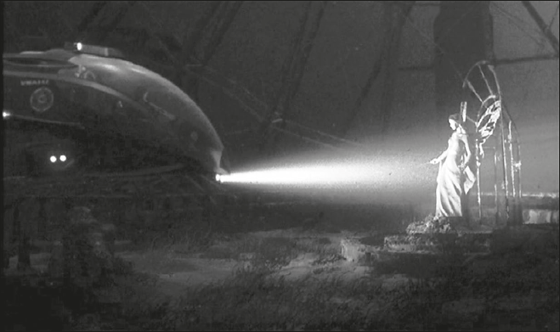

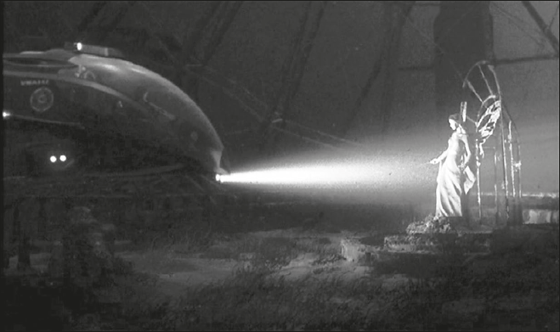

Anything but triumphant cinematic vision, however, this moment, towards which Spielberg’s entire career converges, poignantly underlines that the Imaginary is, by definition, unattainable. What could have been an intellectually satisfying, if downbeat, ending leaves David in an almost diagrammatic image of spectatorship, seated in darkness, gazing along a cone of light in primary identification with an unreachable illuminated figure, behind a screen that is both access and barrier. ‘Sunk in the electrical narcotics of the cinemas’, like popular audiences, according to Dziga Vertov (1926: 23), sustained by a false vision that distracts from effectual activity, David is fated to futile repetition – ‘Blue Fairy, please, please, please make me into a real live boy’ – until his batteries expire and the oceans freeze.

Two millennia later, a hand wipes a blank surface, brushing away frost to reveal David beyond. Shadows play over his face as though from a movie screen, before a benediction gesture – cinema as religion – reanimates him with a light burst. Entering now the diegesis of his vision as was never possible in Persona, David finally touches the Blue Fairy only to see her shatter and collapse. However, the super-mechas who restart David’s freeze-frame within the inscribed reel personify cinema, as did Joe, and reassert Spielberg’s faith by realising David’s Imaginary. They read his discursive formation, expressed as images on their faces which become screens, while David’s eyes close at last, his search over. His blue eyes reopen in close-up on a white screen, an amalgam of cinema’s fundamental elements: he is back at Monica’s, announcing, ‘We’re home!’ the piano again playing. The exterior is blue, however, not green, as he runs through the house with abandon, like Jim in Empire of the Sun, calling ‘Where are you?’ and oversaturated colours and grainy stock emphasise this reconstruction’s cinematic artificiality. A female voice allures him: the Blue Fairy, not Monica – a metonymic consolation for the lost object. ‘You’ve been searching for me, haven’t you?’ she asks. He replies, ‘For my whole life.’ This scenario then recedes, as an externalised camera position confirms it to be a movie watched by super-mecha spectators. Their circular screen exactly matches an earlier shot, seconds before news of Martin’s recovery excludes David, of Monica reflected in a shiny glass hob, cooking. Light shines behind David’s head now as the super-mechas communicate via the Blue Fairy, confirming how important to them his ‘uniqueness’ is, which he always craved.

Assuring David, ‘Your wish is my command’, the Blue Fairy, after David has wept that Monica cannot return, restores her for one day from the lock of hair kept by Teddy. The chrome mobile reappears. David, playing with a toy amphibicopter, remembers Joe: rather than regression to an earlier state, this is imaginary projection, anticipation grounded in current knowledge and desire. A knock at the door heralds not Mummy, but a super-mecha, in a recurrent Spielberg identification device that deceives or surprises the spectator and protagonist together. Clunking expository dialogue finally leads to the exterior becoming natural and David walking through blinding light and a ribbed glass screen to where Monica is awakening alone in the marital bed. The screen whites out to that imageless purity, purgation of the Symbolic, which Neary enters in Close Encounters, as David strokes her hair: a healing repetition of the traumatic instant of castration when Henry leapt out of bed, removed the scissors, and afterwards engineered David’s banishment.

David fulfils his desire to please, making Monica coffee in the dazzlingly backlit kitchen. Having once promised him ‘tomorrow’, she is unaware what day it is; ‘Today’, David tells her, film always unreeling in a perpetual present. Multiple mirrors now redouble rather than fracture the image as Monica dries and combs David’s hair, a further white-out accompanying the voice-over narration that ‘there was no Henry … no Martin … no grief’ – that is, no patriarchy to constrain the utterly artificial ‘TV-commercial-like perfection’ (Robnik 2002: 7). A light shaft flares as Monica declares her love and David sheds a further tear as she returns to bed. Eventually he closes his eyes voluntarily for the first time – a real boy, he believes – and the camera tracks discreetly back, leaving him sleeping with Mummy where, the voice-over explains, ‘dreams are born’. This emollient phrase, however, disguises the origins of both nocturnal and silver screen dreams in unresolved tensions and traumas. Kreider recalls that the happy incidents in David’s day with Monica, causally connected, each rewrite a disaster (2002: 38): the hide-and-seek game compensates for her incarcerating and abandoning him, the haircut for his chopping off her lock, and the birthday party for the afternoon he almost drowned Martin.

Realism and fantasy

Realism is an issue both in A.I. and its reception. Hoberman ridicules the ‘hilarious morass of Ed Wood gibberish’ (2001: 17); Mendlesohn criticises the ‘scientific gobbledygook’ the movie resorts to in explaining its premises because it is unsure of its audience, as well as implausibilities such as David having an oesophagus, the unlikelihood of a psychologist recommending a robot ‘replacement’ to bereaved parents, and ignorance of the destruction ice wreaks on trapped structures (2001: 20). For Hoberman, however, ‘The movie’s appeal is not to reason. Its psychological terrain is far closer to the magical realms of Hans Christian Andersen or E.T.A. Hoffman than to sci-fi as we know it’ (2001: 17). Certainly this ‘bastard son of Sigmund Freud and Walt Disney’ (Charity 2001: 85), as well as Kubrick and Spielberg, is easily reducible to formulaic structures: David as ego, Martin the id, and Teddy the super-ego.

A.I. declares itself not merely a film but a DreamWorks product, apparently acknowledging Freudian implications of the company’s brand name. A plaque featuring the studio’s crescent moon logo identifies the Cryogenics ward where Martin slumbers amid fairy tale murals. The figure recurs: in a rug and a light that haloes David in the nursery with its clouds wallpaper that also recalls the logo; in a light behind David during the first dinner scene; as well as in the perspective framing of a round window before which Monica rejects David and, ultimately, a super-mecha animates his dream. The clouds reappear in a shadowy, Hitchcockian vein, as headlight patterns on the wall when David cuts Monica’s hair. Furthermore the roar of giant waves, signifying global warming, accompanies the opening logo instead of the familiar, reassuring guitar and orchestra. The director with the clout to authorise this change asserts a bleak realism, reinforced in the understated white-on-black credits.

David’s ‘monomaniacal obsession that renders him oblivious to the ugly realities around him’ (Kreider 2003: 36) parallels what commonsense accounts of entertainment call escapism. Orgas attend flesh fairs or sleep with robots while the ice caps melt. David’s final happiness ignores human extinction, no less, just as some critics argue Schindler’s List provides an upbeat substitute for confronting the Holocaust. Conversely, Drehli Robnik (2002) argues, David’s memory keeps the human race from oblivion. Preserved and narrated by a super-mecha voiced by Ben Kingsley – whose Schindler’s List character was witness and enabler – it reasserts Spielberg’s faith in popular cinema as cultural memory: ‘Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.’ Equally, in seeking to recreate human ‘spirit’ in further striving for the Imaginary, the super-mechas are absolutely misguided. ‘Surely human beings must be the key to understanding the meaning of existence’, states the narrator, citing art, poetry and mathematics. However, Kreider sardonically observes, all ‘human beings do in this film is fuck and destroy robots, and each other’ (2002: 38).

Yet the Flesh Fair, whose audience is exhorted ‘purge yourself of artificiality’, as well as an ironically self-reflexive view of Spielberg’s cinema – he, ‘no less than these rabid rednecks’, Hoberman implies, loves his special effects – ‘might equally represent Spielberg’s view of his critics. (Rather than the fantasy of Schindler’s List, these antimechas are demanding the documentary Shoah.)’ (2001: 18) Then again, A.I. anticipates and articulates such objections. David, proposing he could emulate Pinocchio, insists, as Monica abandons him in a fairy tale forest, ‘Stories are what happens’; she, heartbroken and unable to destroy what she knows is a simulacrum, responds, ‘Stories are not real.’ A.I., exceeding monological discourses that divide critics, stages ambiguities and contradictions, and embraces heteroglossia. David’s unprecedented realism, after all, offends Lord Johnson-Johnson, who, with his religious rhetoric, echoes the effects lobby, while precisely the same quality moves the crowd to David’s defence.

Intertextuality

Metatextuality again transcends postmodern pastiche by alluding to other pertinent themes and contexts. In a film explicitly concerned with story-telling, illusions, psychological needs and their relation to the Real, it furthermore, arguably, increases audience self-awareness, potentially encouraging reflection on textual strategies and associated pleasures and frustrations. The thunder rumbling outside Hobby’s lecture theatre, which resembles a Victorian anatomy room with its slab-like tables, is a horror cliché signifying ‘mad scientist’, especially with the ominous high-pitched synthesised score as he removes Sheila’s processor. Yet the Frankenstein connotations – Hobby likens himself to God creating Adam – exceed generic convention. Just as Mary Shelley’s novel voiced anxieties around scientific progress and social change, Spielberg’s choice of a black woman to raise the ‘conundrum’ of mechas programmed to love – ‘Can you get a human to love them back?’ – places this evolution in a procession, including abolitionism and feminism, of comparable moral problems for patriarchal hegemony. A white, middle-aged, entrepreneurial, male technocrat’s single-mindedness in his multinational corporate headquarters bodes ill against the backdrop of global warming.

References across periods and genres invoke cinema as a reservoir of the unconscious, rendering the fantasy dreamlike yet already known: alternately strange, half-recognised and welcomely familiar. Without curbing his usual broad intertextuality, including numerous auto-citations, Spielberg emphatically emulates the look of a Kubrick movie, as epitextual cues invite audiences to note. Framing David through a doughnut-shaped ceiling light at dinner both haloes him, emphasising his narrative status as Chosen One, and ominously recalls Dr Strangelove’s War Room as domesticity becomes a battleground for technologically unleashed forces confronting humanity with its self-destructive imperfections. Brittle cutlery sounds recall typically awkward mealtimes in Kubrick. Martin’s cryogenic pod evokes Disney’s The Sleeping Beauty (1959), but also hibernation capsules in 2001. When Martin asks if David does ‘power stuff like walk on the ceiling or walls, or anti-gravity stuff’, perceptive viewers might recall Fred Astaire – Joe’s precursor – performing such stunts in Royal Wedding (1951), replicated for artificial gravity effects in 2001. As Kreider states, the scene with Sheila recalls ‘the grotesque piece of theatre in A Clockwork Orange in which prison officers and politicians applaud as Alex is debased and bullied … It is the audience, not the subject, whose emotional responses are tested’ (2002: 34) – and one might conclude both films’ audiences are meant to find the diegetic audiences’ lacking. Hobby’s office, outside which the amphibicopter docks in a bay modelled from 2001, recalls how in that film an ape evolves paradoxically into a weapon yielder: like HAL, the artificial intelligence that marks the peak of further evolution in 2001, David is a killer. The smashed mecha and subsequently discovered copies, confirming both are mass-produced commodities, further the paradox: David, who previously refused to break toys, is only a murderer if he and it are human. David’s creepy qualities – his unsettling stare, the closed loop of his programmed obsession – retain a non-human quality that prevents him from becoming entirely sympathetic and are at the heart of the film’s ambivalent reception. Otherness prevails even when an unequivocally sentimental film would have portrayed him as closer to a ‘real boy.’. At the end of his ‘only child’ sojourn with Monica, David eerily relays a telephone message in the caller’s voice. This recalls not only Spielberg’s recurrent theme of translation linking protagonists at the interface between levels of diegesis, but also, ominously, the boy’s apparent possession in The Shining – referenced already in the shot following the Swinton’s three-wheeled car that recalls his tricycle. The ‘murder’ scene echoes a ‘massacre’ of fashion mannequins in Killer’s Kiss (1955), while revealing, as in a Kubrick narrative, David’s destiny to be contained within a bigger, unexpected plan.

Tonal discords accompany David’s confrontation with himself, similarly to Bowman observing his older self in 2001. David, though, neither ages nor grows. As he floats, immersed in light, after attempting suicide, resemblance to Kubrick’s starchild is ironically, chillingly hollow. Obsessive solipsism, a humanly implanted replication of human selfishness, rather than a cosmic breakthrough, predicates David’s survival. While the rapid flight over ice fields recalls Bowman’s stargate journey and the camera passes through a future craft composed of 2001-style monoliths, the sequence in the reconstituted house where David, like Bowman, finds himself at a dining table, is an end in itself, not a way station. Finally David, although believing as some audience members may (especially those who find the movie saccharine) that he is closing his eyes to drift away into maternal bliss, forgets he is a defunct machine trapped in a frozen waste. Worse, the super-mechas, by downloading his synthetic desire in order to reconnect themselves to the humans who spawned them yet departed, retain enough flawed humanity themselves to enter the futile loop by vicariously participating and pursuing their own Imaginary. They join David – whom Kreider likens to Jack in The Shining, trapped in a photograph, ‘happy and fulfilled, finally home, frozen forever in Hell’ (2002: 39).

Subject positioning

A.I. progresses schematically, richly allusively, conscious intertextuality challenging monological readings. Intriguingly cerebral, it fails as mainstream entertainment. It undermines its apparent premises and ironises the pleasures, whether associated with realism or fantasy, ordinarily contracted with blockbuster audiences. At no point does this movie (which with typical Kubrick mischief names the psychiatrist who catalyses the entire plot ‘Dr Frasier’ after an inept sitcom character) approach the authenticity or sustained Imaginary involvement it appears knowingly to reflect upon as part of David’s yearning. Its contradictions self-cancel. David, unlike Collodi’s original, does not develop in his quest. The tragedy, a word applicable here only as a conventional term, is that his emotion, while real – he is programmed, like a human, to feel it – means nothing. Consequently, neither does the emotion the movie ostensibly appears to strain after.

Initial focalisation with Monica stresses David’s otherness. A shift occurs, with awareness of David’s jealousy upon Martin’s entrance. Neither overtly expressed nor performed, however, this is spectatorial projection. Facilitated by Martin’s initial half-machine appearance, such empathy is the nub of the film. Roger Ebert argues that David ‘only seems to love. We are expert at projecting human emotions into non-human subjects, from animals to clouds to computer games, but the emotions reside only in our minds’ (2001: 6), a view that chimes with Anne Friedberg’s theorised account of identification with non-human characters (1990). From this, Ebert concludes the answer to the Cybertronics seminar question – ‘What responsibility does a human have to a robot that genuinely loves?’ – is ‘none’ (2001:6). However this is less simple. If pre-programming means David’s capacity to love is not real, where does that leave human parental or filial love, evolutionarily and psychosexually programmed? Henry’s logic, meanwhile, is flawed, machine-like and incompassionate as that of any HAL, his Oedipal rationalisation predicated on a non sequitur: ‘If [David] was created to love it’s reasonable to assume he knows how to hate.’ Monica realises again David is a machine when, during his operation, he assures her, ‘It’s OK, Mummy, it doesn’t hurt.’ The film fails whenever the audience forgets he is a mecha, as the synthetic emotion appears sentimental and false as human drama, whereas this is precisely the point the movie addresses through focalisation via David – a robot programmed, remember, to feel as a ten-year-old. His reaching for Joe’s hand at the Flesh Fair is the key moment of human sympathy that links with E.T., Always, Schindler’s List and Amistad and divides those films’ critics; it occurs as the diegetic audience, who think they are celebrating authenticity by disposing of artifice, confront mortality by watching its symbolic enactment, rendered painless, by technological substitutes.

It is a short step to the mecha conversation at the Flesh Fair about how ‘history repeats itself’ as orgas strive to ‘maintain numerical superiority’ by apparently perpetrating atrocities to reassert difference. Yet when the Flesh Fair proprietor calls, ‘You! Boy!’ it is doubtful many spectators question David’s acceptance of the interpellation. Focalisation aligns us with David and against – as at the start of E.T. – our fellow orgas. Difference, then, on which the narrative is predicated, is severely problematised, leaving in place more questions than are answered.