Following critical and box office disappointment that soon caused A.I. to ‘fade into obscurity’ (Gomery 2003: 79), damage limitation appears to have extended to playing down Spielberg’s involvement in Minority Report. Marketability depended on promoting Tom Cruise in an action thriller, rather than Spielberg directing science fiction, despite his long-standing association with the genre and the two movies’ similar setting and visual style. Indeed Spielberg’s name was absent from billboard advertisements. Yet Minority Report embodies and extends the director’s most interesting and typical concerns.

Seeking clarity

The ostensible narrative begins with a rapid montage portraying a murder. Bleachedout hazy shapes rack focus: a couple making love; scissors; a man climbing stairs, optically distorted to suggest mental derangement but incidentally emphasising the film plane; discontinuous dialogue. Tantalising glimpses of lust, violence and melodramatic emotion, accompanied by disturbingly percussive, echoing sound, recall a movie trailer. Close-ups on eyes – The murderer’s? The victim’s? An onlooker’s? – culminating in an extreme close-up on an iris, underline the enigma. Similarity to key shots in

Psycho and

2001 evokes both Hitchcock’s thrillers and Kubrick’s science fiction. Pointed scissors penetrating an eye in a cardboard cut-out – patently a reference to

Un Chien Andalou (1929) and, especially pertinently, Dali’s dream sequence for Hitchcock’s

Spellbound (1945) – allude to visceral and psychological horror, specifically associated with the vulnerability of eyes and the guilt of voyeurism.

Minority Report consciously aligns with modernism and the art-house tradition.

In a sense this sequence is a trailer. Establishing the tone, generic expectations and enigmas according to which the film, which elaborates the same narrative, is understood (a science fiction mystery thriller concerned with the theme of vision and containing some Bergmanesque mise-en-scène and metaphysical explorations) it also briefly previews, like a trailer, a forthcoming event. That this foreshadows a definite narrative occurrence, were the warning not heeded, parallels in mise-en-abyme the function of the movie itself and its defining genre in predicting a preventable future. Like any trailer it also stimulates desire by presenting a trace of a film not yet seen, redoubling the notion of present absence, an Imaginary signifier.

Agatha’s (Samantha Morton) large eyes and shaven head, together with her blank white background, locate the Pre-Cog, whose vision this is, in a line of mystical Others in Spielberg’s science fiction. She is, furthermore, another personification of cinema. Not only a star within the diegesis, attracting tons of fan mail, she also receives visions and projects them onto a screen in the so-called Temple she and her two fellows inhabit. Its dark, quilted walls and geometrically interspersed spotlights would pass for a movie theatre. The rectangular window looked through by Anderton (Tom Cruise), the active surrogate directed according to her visions, flanked by speakers amplifying his voice, in this analogy inscribes a screen. So, reciprocally, does the surface of the ‘photon milk’ suspending her (light as nurture!), which she breaches whenever engaged in the action, sinking back when less involved in her unfolding dreams. Amniotic associations compound the analogy with cinema as maternal Imaginary.

The opening prophecy, interspersed with, on first viewing, incongruous violent splashes, instating an image system of water, retrospectively positions the spectator with Agatha. The peritext of the Twentieth Century-Fox and DreamWorks logos and the titles confirm this apparent identification: all, oddly for a colour movie, are monochrome and ruffled by surface ripples that link directly to emergence of the seeming epitext of the ‘trailer’. The water contains the diegesis (Minority Report’s dystopia) and non-diegetic paratexts (inscription of institutions behind its funding, production and distribution), rather like the dissolve from the Paramount logo that opens Raiders of the Lost Ark. So too do product placements that, paradoxically, substantiate the nightmarish foretelling. Penetration along the z-axis of the water/screen surface by Agatha as spectator (reverse of Jurassic Park’s velociraptor threat) is, spatially, a similar liminal crossing.

The far-reaching implication: all of Minority Report is Agatha’s (or our) dream. Cold, blue colour links most of its narrative to Agatha’s initial vision, not unlike the green tinting of The Matrix, implying that it too unfolds in an alternate reality projected from the mind of the participant-spectator/protagonist, immobilised yet incorporated in the action. (For confirmation, compare Ghost in the Shell (1995), a Japanese anime that clearly influenced mise-en-scène and thematic concerns in The Matrix, A.I. and Minority Report. DreamWorks distributes its sequel.)

Once the plot mechanism comes into play, literally realised in the ‘lottery ball’ contraption the Pre-Cogs trigger, self-reflexivity imbues the action. Its pervasiveness and centrality advance this aspect of Spielberg’s practice beyond anything since

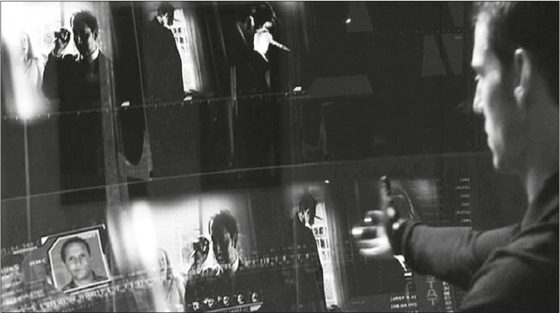

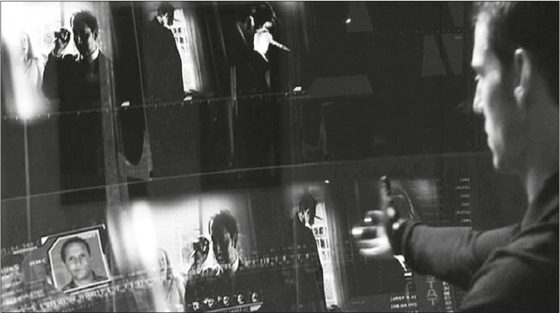

Close Encounters. Anderton, ahead of the camera, enters through a sliding glass door. Lettering on the door moves laterally off-screen like a caption, succeeded by extradiegetic captions that anchor setting and period: the Department of Pre-Crime, layer upon layer of transparent screens, between which suspended walkways echo the chute for the wooden balls. The Pre-Cogs’ circular bath, viewed overhead, is both a movie reel and a lens. Video screen witnesses to Anderton’s investigations and fellow officers, to whom the film cuts at crucial moments, are inscribed spectators: ‘Oh, I love this part’, says Anderton’s sidekick, like a voluble moviegoer, as one investigation starts. Classical music provides intra-diegetic accompaniment and the lights dim as for a movie; we look back through a screen of moving images while Anderton voyeuristically spectates, seeking mastery over the fragments, and indeed edits before our eyes the clips we are about to see from shots already seen. Numbers at the edges of Anderton’s screen suggest the writing on filmstrips and the time code burned into footage for editing. Virtual knobs he turns to freeze, advance and reverse frames are futuristic shuttle controls.

Whether the coherent suburban images relate Anderton’s subjective perception of the precognition, or constitute narrative crosscutting within the present tense, remains unclear. Either way, his seeking clues in the mediation, which when the image fills our screen is crammed with disorientingly rich mise-en-scène, not yet dissected according to continuity principles, recalls other self-reflexive movies such as Blow-Up (1966) and The Conversation (1974) while enacting the spectator’s unfolding comprehension. This positions viewers externally: as spectators – our view presumably matches the witnesses’– yet also projectively involved in the crime fighter’s work. He, in further twists, shortly fulfils the impossible desire of spectatorship by intervening in the narrative his comprehension constructs.

Minority Report – conducting an investigation in the editing suite

Inchoate fragments from the Pre-Cogs coalesce into the same form and diegesis as the framing movie, as Anderton seemingly imposes conventional editing. ‘Howard Marks, where are you?’ he asks, followed by a cut to a woman’s voice, ‘Howard’, as a man leaves a house, this name having initially appeared in close-up on the wooden ball: the Hollywood rule of three. A lawn sprinkler emits a projector sound (there is no music in the remediated diegesis): one of many circular motions that gradually cede to what appears to be linear narrative. Repeated close-ups on scissors, the predicted murder weapon, metonymically inscribe Anderton’s cutting-room activity, while the eye penetration, repeated, cements the relationship between this and the previous vision. Here the face is recognisably Abraham Lincoln and the child with scissors recites from the Gettysburg address: a first hint about Constitutional repercussions of the Pre-Crime programme we immediately hear about as Federal Agent Witwer’s (Colin Farrell) arrival motivates overt narration. Spielberg’s characteristic backlighting, realistically justified by a large, white conservatory, presents Marks’s fragile family ideals as a dazzling projection from which, in a Bergman-like composition, the darker adjoining kitchen separates him. The vision foregrounds the husband’s voyeurism as his wife’s lover enters the house, the sprinkler sound again resembling a projector while also rhythmically heightening tension.

Anderton verbalises minute observations for forensic purposes but also, as discours in effect, inviting equally close spectatorial scrutiny. Multiple frames slide across Anderton’s screen, stroboscopically shifting as on a Zoetrope. The merry-go-round that explains the puzzle of a small boy oscillating between frames, with Anderton’s image superimposed, reinforces this metonym visually.

Mirrors and edgy, hand-held camerawork intensify the action, further underlining reflexive structures. The lovers are doubled. Howard, intensely backlit, raises the scissors. A mirrored door closes, bringing him, in darkness, into the same diegetic space as the brightly-lit adulterers, like a continuity cut. Flash pans inscribe in point-of-view shots Anderton’s actively searching gaze, duplicating the spectator’s, more explicitly than would glance/object editing. ‘The cinema depends on a series of mirror-effects organised in a chain,’ argues Metz (1975: 53); here rendered apparent. ‘Which house?’ Anderton asks, articulating the hermeneutic. The merry-go-round strobes his image, enhancing scopic stimulation in a manner similar to Spielberg’s solar wind, disclosing and threatening to remove the ego-ideal: an intensified fort-da game that transforms banal narcissistic identification into something closer to jouissance.

Witwer, designated official ‘observer’, superimposed over the Pre-Cogs or looking through a widescreen window at the departing officers, watches the watchers. He embodies an enclosing discourse, a further relay of the look that permits troubling conscious awareness in the shifting focalisation. In short, without causing alienation these structures refuse comfortable identification with the protagonist one might expect in a mainstream movie. Witwer appears to enable a metanarrative against which to gauge the present-tense green, grainy diegetic ‘reality’ and the Pre-Cogs’ enclosed blue, grainy vision, while the murder plays out, backlit, against a huge and highly improbable rectangular window, an inscribed wide screen.

Knowledge and vision thus initially equate, and an ocular leitmotif advances as when Marks, ready to kill his wife and her lover, repeats a conversation heard in the kitchen: ‘I came for my glasses. You know how blind I am without my glasses.’ The spectacle appears literally through one of the spectacles. Rapid montage ensues, in which Marks holds his glasses and the scissors in the same hand, emblematic of

Psycho’s equation of vision with aggression. Anderton rushes upstairs, occluded by banister rails that impose a stroboscopic effect. Officers abseil through a ‘widescreen’ skylight, penetrating the apparent projection surface, and Marks’s hand holding the scissors smashes through a window. ‘Look at me’, Anderton orders Marks, projecting a beam into his eye for optic identification: harnessing his vision and interpellating him firmly into the Symbolic as he arrests him, then immobilises him, for a potential crime. Meanwhile the Pre-Cogs, observed by Witwer, are increasingly agitated, intensely engaged spectators of the scene they themselves project while mouthing the dialogue. Wally (Daniel London), their carer, ordered to ‘erase the incoming’, in effect switches them off as they settle into peace and their screen fades. They are, literally and metaphorically, human projectors.

A Government commercial extols Pre-Crime; a retrospective explanation, like Jurassic Park’s Visitor Centre presentation. A cut then dissimulates this as not discours addressed to the spectator, but rather a projection onto walls in the squalid inner city where Anderton is jogging, an indication of audiovisual advertising and propaganda’s extensive reach. The commercial introduces the programme’s head, Lamar Burgess (Max von Sydow). His name (apart from partially coinciding with Ingmar Bergman, for whom the actor playing him starred many times) alludes to the author of A Clockwork Orange, a novel concerned with free will and ethical limits of crime prevention (Vest 2002: 108). The tribute is later emphasised by eyelid clamps that incapacitate Anderton during surgery (performed by a character played by another of Bergman’s company), similar to those in Kubrick’s adaptation that force Alex to watch violent footage. The commercial includes the phrase ‘and the pursuit of Happiness’: an inalienable Right, along with Life and Liberty, from the Declaration of Independence, compromised by Pre-Crime.

A blind drug dealer recognises Anderton before the latter, seeking to buy ‘clarity’, sees him. Visual evidence – the premise on which both detective movies and Pre-Crime operate – is thus questioned. In a Grand Guignol moment that exploits voyeuristic fascination and its disturbing consequences, the dealer removes his shades to reveal sockets, proclaiming, ‘In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.’ Only an eyeless individual, operating outside the political economy regulated by optic surveillance, enjoys freedom in the Land of the Free.

Clippings by Anderton’s bedside of reports of returned missing children register deep personal trauma, affirmed by his apartment’s untidiness, ‘neuroin’ inhalers scattered everywhere. Together with an excess of family portraits, they signal Spielberg’s recurring theme of parent/child separation. This obsession, related to psychoanalytic ramifications of narrative cinema as quest for lost object, thus affirms ‘the film’s ongoing subthemes – addiction, grief and addiction to grief … with addiction to images as the primary metaphor’ (James 2002: 13). Although first we view Anderton through a screen as he eats from a cereal packet decorated with noisy animated cartoons, the camera arcs through the 180-degree line and aligns with him as spectator as the whole wall becomes a movie screen. Bulbs flicker in close-up, evoking archaic cinema technology despite the futuristic setting. Anderton’s distant reflection with a beam overhead explicitly likens his home, as much as his workplace, to a movie theatre as the camera pulls back to reveal him in the foreground with another beam apparently projecting from his eye. His son Sean’s hologram steps out of the scene along the light beam – literally, leaving a shadow hole in the background, like Peter Pan, another boy never to grow up. Absence becomes present for Anderton, who actively projects himself into his projected memory, speaking in unison with his recorded voice, identifying totally with his scopic Other. Like the Pre-Cogs he is a participant spectator, except he views the past, they the future: a parallel emphasised when screen reflections of water shimmer over his face. Streaks flowing out behind Sean’s image along Anderton’s eye-line afford the most explicit confirmation yet of Spielberg’s equation of his solar wind with projective vision. ‘A sort of stream called the look … has to be pumped into the world’, in Metz’s analogy, ‘so that objects can come back up this stream … arriving at last at our perception’ (1975: 53).

Minority Report joins numerous recent art movies that, Emma Wilson shows, self-reflexively interrogate cinema, often incorporating ‘home movie’ footage, as commemoration of and response to loss, particularly of children (2003: 13).

Inhaling ‘clarity’ before viewing his wife’s spectral image, Anderton relives her urging him to ‘put the camera down’. This completes inscription of the cinematic apparatus (‘I am the camera, pointed yet recording’, says Metz (1975: 53)). Resemblance to a scenario in Peeping Tom (already referenced in the name Marks, shared by the earlier self-reflexive film’s screenwriter and protagonist, and later when officers pursue Anderton to Powell Street) potentially communicates a psychopathological aspect to Anderton’s cinephilia. A side view renders the hologram flat and insubstantial (as if on a screen) despite its presence for him. As the camera crosses behind it, it regains pseudo-perspective, maintaining real-life proportions for him just as a movie spectator, sliding into the Imaginary, disavows the projection’s unnatural size and two-dimensionality. Traversing the plane, we voyeuristically observe the couple’s intimacy yet are addressed directly (to camera) as what would normally be part of a shot/reverse-shot is superimposed to place Anderton and Lara’s (Kathryn Morris) image into a two-shot. Like him, we become simultaneously involved and detached – invited to identify, yet distanced by formalism – poised, or alternating, between Imaginary and Symbolic. Pathetic fallacy – rain-streaked windows – brings the scene to a conventionally sentimental close, yet Anderton’s narcotic dependence and disturbed personality reinforce the complex effects of multiple focalisation, discouraging easy identification. He apparently has ambiguous depths like a Hitchcock protagonist and, while focalisation often aligns us with his experience, is no simple hero. When, later, the Pre-Cogs identify him as a killer, we are no more confident than he, who believes in Pre-Crime, of his innocence.

‘Can – you – see …?’

Minority Report seemingly unfolds from subjectively inflected claustrophobic drama to exploit spectacular science fiction and action-adventure effects. Anderton speeds along elevated freeways in a

Metropolis (1927) cityscape. Lens flare, artificially contrived, as this is clearly a computer-generated shot, enhances realism, facilitating Imaginary involvement. It also flaunts textuality by potentially drawing attention to the (nonexistent!) camera, craft technique and Spielberg’s typical inscription of projections. These, together with allusion to generic precursors, encourage Symbolic awareness. That the ribbons of roadway resemble loops of film hardly seems fanciful in this context. They evoke the television system in

Things to Come (1936) that consists of transparent strips suspended between buildings, on which frame grabs flow like the clear sheets on which images in

Minority Report are stored and viewed.

Walkways in the Pre-Crime headquarters, divided like film strips into frames, infinitely multiplied in surrounding glass surfaces, confirm this similarity. To enter is to become entangled in cinematic imagery. Entry requires furthermore an optic scan from a device that resembles an eyeball, figuring reciprocity of vision on which social surveillance, like the ideological apparatus of cinema, depends – after all, the personalised commercials Anderton encounters on the street are literal interpellations. Viewing Burgess and Anderton behind layered screens and railings is voyeuristically intriguing and places them, indeed imprisons them, within a textually inscribed cinematic diegesis. When Anderton, silhouetted, looks up admiringly to Burgess as a superior figure as if on a screen, or when, later, at Burgess’s house, blinding shafts backlight him from Anderton’s perspective, the Oedipal implication, as with Jim’s view of Basie or Upham’s of Miller, compounds metaphors of psychic and cinematic projection.

When Witwer states Pre-Crime’s ‘fundamental paradox’ – ‘It’s not the future if you stop it’ – his words equally apply to dystopian satires and, more intriguingly, to what I shall eventually argue is the movie’s outcome. Anderton’s response, after rolling a ball that Witwer catches – ‘The fact that you prevented it from happening doesn’t change the fact that it was going to happen’ – echoes a movie plot’s inevitability, predetermined by scripting and filming, always already finished except for the spectator, endlessly repeating like a Zoetrope, yet seeming from within the experience to unfold linearly:

a little rolled up perforated strip which ‘contains’ vast landscapes, fixed battles, the melting of the ice on the River Neva, and whole life-times, and yet can be enclosed in the familiar round metal tin, of modest dimensions, clear proof that it does not ‘really’ contain all that. (Metz 1975: 47)

And yet, the film hints by using Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony in the ‘editing’ scenes, completion and closure are not always achieved.

Pre-Crime officials and Pre-Cogs keep ‘strict separation’, like the voyeur and the object of desire, a point underlined when Wally insists, ‘I can’t touch you!’ after the dividing screen is ordered open. Like stars – whose glamour occupies a different order of existence from ordinary moviegoers, and who provide space within narratives for fantasy precisely because their

being rather than

performing feels as if it is caught unawares, offering voyeuristic satisfaction (Ellis 1992: 99) – ‘It’s better if you don’t think of [Pre-Cogs] as human.’ ‘No, they’re much more than that’, muses Witwer as the camera tilts to display the glittering firmament inside the Temple: ‘Science has stolen most of our miracles. In a way they give us hope – hope of the existence of the Divine.’ Yet their serotonin is monitored so they neither sleep too deeply nor are too awake. (‘It is easier to fall asleep in a film than is often admitted’, Ellis insists (1992: 40).). Participants in Metz’s ‘cinematic fiction as a semi-oneiric instance [and] mirror identification’ (1975: 18), they reciprocally register the returning current. Between Witwer breaching ‘the segregation of spaces that characterises a cinema performance’ (Metz 1975: 64) and the ensuing disastrous events there is implicit correlation if not direct causality. If Anderton did not find himself inside the Temple, Agatha could not communicate directly her minority report, he would not commence his independent investigation, and Burgess would not require his removal.

Whatever the narrative motivation, the movie continues as a heady cornucopia of quotation and allusion, to specific movies and cinema generally, too rich to detail – with, I argue later, anything but frivolous implications. Although it might seem irrelevant to liken Agatha’s unexpected warning to Anderton to the protagonist’s gaining of burdensome responsibility in The Man Who Knew too Much (1934/1956), or the way she slips back underwater staring at her hand to the 2001 Starchild, the next scene should dispel any doubt: the Department of Containment. In this vast, literal panopticon, immobilised convicts’ thoughts play before their eyes on imprisoning glass cylinders, which project beams above them reminiscent of the Twentieth-Century Fox logo at the start. Gideon, their jailer, plays an organ to ‘relax’ them. Underlining his Bible Belt religiosity, this equally – shifting from extra-diegetic to diegetic status, again blurring screen boundaries – evokes a cinema Wurlitzer, its organ pipes replaced by stacked tubes rising impressively from the bottomless pit, and is perhaps also an auto-citation (Close Encounters). While narrative focuses on significant action unfolding on a high-tech screen centred in the composition, a child’s revolving lampshade from the 1950s occupies a third of the frame in the foreground. Cowboys and Indians chase endlessly around an illuminated parchment contrasting in colour with everything else. This proto-cinematic novelty peripherally acknowledges generic origins of the chase movie Minority Report becomes, while the shot overall – the screen in front, light projected over Anderton’s shoulder, the organ in the background – concurrently inscribes cinematic history and spatial arrangement.

Extraordinary technique fetishises cinematic practice for its own sake. In one 13-second shot the red ball spirals in oscillating close-up down its transparent tube; focus racks onto Anderton’s assistant in the background, then shifts again as he advances before a hand in big close-up grasps the ball; a tilt up pulls focus on the assistant’s face and the camera pans right to the ball in Anderton’s hand; focus adjusts once more so his name on it becomes legible. Such painstakingly brilliant yet easily readable filmmaking is at once invisible narration and bravura display, eliciting a response from form as much as content, unsettling spectatorial positioning at whatever level of consciousness it is registered.

On my first viewing it was not until, in a subsequent escape, Anderton kicked out the window of a car travelling vertically several hundred metres up the side of a building and started jumping between vehicles – a futuristic variant on silent-movie chases along railroad cars – that incredulity intruded. I had accepted every preposterous premise. At this point, when Anderton breaks through the screen to face the world alone, like Jim in

Empire of the Sun, ‘reality’ most resembles a Hollywood adventure.

Anderton’s existence is movie-saturated, mediated. Commercials, not merely glanced at or ignored, constitute a virtual environment. Anderton’s picture emerging on constantly updated

USA Today covers as he sits nervously trapped on a train ratchets up a suspense device from

The 39 Steps. Fight sequences when he escapes arrest – first in The Sprawl, utilising rocket backpacks and flaming explosions as well as ‘sick sticks’ that elicit a haptic, visceral audience response; later in the novel setting of the automated car factory – mount a serious challenge to Bond films. Windows and floors are repeatedly penetrated, while a father sits passively watching television amid Spielberg’s most extravagantly spectacular action; fantasy and mundane reality meet, light-heartedly and amusingly, as jetpack exhausts ignite hamburgers broiling on a stove. In the assembly plant, dazzling lights into camera underline this set piece as

cinematic. Nevertheless

Saving Private Ryan’s fast shutter-speed recurs, stroboscopically inscribing artificiality yet evoking the cold clarity of immediacy and presence. This hyperrealist device renders spectatorship both involved and detached.

‘KEEP OUT – NO TRESPASSING’ signs, as at the start of Citizen Kane, guard Iris Hineman’s (Lois Smith) lush, overgrown garden. Anderton scales walls topped – significantly, as will become apparent – with broken glass to enter this flawed Eden, with its Medusa-like genetically-modified phallic creepers: a shattered Imaginary (Hineman jokingly describes herself as ‘the Mother of Pre-Crime’), a lesser Jurassic Park, where he seeks answers. Hineman potters in a huge greenhouse, the safe place of light and life hitherto encountered in E.T., Empire of the Sun and Amistad (her manner and vocal delivery recall Quincy Adams). Yet she is a darkly ambiguous nurturing mother, embodying what Barbara Creed (1989) calls ‘the Monstrous Feminine’ – a well-intentioned scientist whose experiments to treat children of neuroin addicts created Pre-Cogs as a side-effect, many of whom died in the refinement of the programme she accepts is imperfect. She lovingly tends her plants and brews herbal tea to cure Anderton’s poisoned wounds, yet is coldly detached concerning Pre-Cognition. She evidences unsettling sado-masochism when demonstrating a point by almost crushing the life out of a seemingly sentient plant but not flinching at the vicious cut it inflicts. She wears a dark, halo-like brim as Anderton asks, disbelievingly, ‘Are you saying I’ve haloed innocent people?’ and she kisses him, sexually, on the lips after imparting the desired information about minority reports. Her characterisation is not entirely misogynistic, despite her point about females being always the most gifted, as the decadence of Burgess, her former associate, hinted at in the profusion of flowers bedecking his home, counterbalances it. Nevertheless it makes clear there is, for Anderton, no going back, no return to comforting Imaginary innocence.

In this lapsed utopia science produces dangerous addictive drugs and excuses for imprisoning the innocent, sacrifices children for progress, but has not cured the common cold. Anderton sniffs, Witwer coughs, and Burgess drinks herbal tea and honey. The gross-out eye transplant that grants Anderton anonymity, but also conveys the idea of new vision, starts with the back street surgeon dragging a string of mucus from his nose. The grotesque body, emphasised in the hideously made-up nurse and the dismemberment intimated in excavated eyeballs, combines with inversion of authority and sanitary procedures, together with abandonment of decorum, in the context of a festival of film allusions. Carnivalesque undermines monological realism, twisting generic expectations to encourage playful and flexible responses. From Spielberg’s point-of-view, perhaps, the colourised versions of old movies playing unregarded, audiovisual wallpaper interspersed with commercials, summarise this culture’s obscenity. That Anderton once had the surgeon convicted for sadistic procedures he filmed as ‘performance pieces,’ as the dialogue recounts against the video-projected background of brutal killings, problematises our pleasure: we don’t

have to watch. Simultaneously it inscribes a history of crime movies and romantic heroism (

The Mark of Zorro (1940)) that then raises the likelihood of spotting allusions to

Blade Runner (1982) (a plastic bag containing eyes) and

Farewell My Lovely (1944) (the detective vulnerable with eyes bandaged).

Blinded, Anderton relives his separation from Sean. The swimming pool recalls the Pre-Cog tank, and crucially, establishes Anderton’s capacity for immersion. A richer, although still artificial, colour spectrum makes this the film’s most vivid scene. Rapidly panning point-of-view shots as Anderton panics, looking for his lost child in an indifferent holiday crowd, clearly cite Jaws.

The business with the rancid milk and sandwiches exemplifies spectatorial duality. It facilitates focalisation through Anderton on a visceral level, necessary in that visual identification with blindness is difficult to achieve if, as here, the audience needs to see more than the character (his face appears twice on television as a wanted man), rendering our relationship with him explicitly voyeuristic. It also confirms that voyeurism is sadistic (Metz 1975: 63).

Voyeurism and detachment from Anderton continue as former colleagues send ‘spyders’ into the apartment block where he hides, and overhead camera movements track their progress, from a dominant position of surveillance as if through the ceilings, while private activities – lovemaking, a domestic quarrel, defecation – cease momentarily for the State to check citizens’ identities. The camera then descends through a roof fan, replicating a celebrated effect from Citizen Kane, to realign with Anderton and show how his new eyes fool the authorities’ system.

Having changed his ‘look’ in another sense with a facial deformer provided by the surgeon – a trace, presumably, of a sub-plot excised in the final cut – Anderton liberates Agatha from Pre-Crime and, in a further imbrication of self-reflexivity, takes her to a virtual reality palace where punters pay to have fantasies simulated. As the proprietor, awed by Agatha, attempts to download her minority report, Anderton asks, ‘Are you recording this?’ and he is not – a studio floor error, plausibly, with which Spielberg is familiar. She projects instead Ann Lively’s murder, shown on our screen as well as intra-diegetically, in reverse, once again accentuating textuality. Following this, she protects Anderton from Pre-Crime pursuers by anticipating every action. This confirms her powers as genuine, suggesting Anderton will murder; yet her intervention causes events, paradoxically creating destiny according to the predictions – self-fulfilling prophesy, as his previous agenda traps him.

The reception desk in the hotel, where Agatha predicted Crow’s (Mike Binder) murder, looks like a cinema box office. In a shot modelled from

Persona, as Anderton and Agatha form a Janus-faced image, suggestive of merging of identity or personalities, she reminds him he is free to depart. Yet desire for knowledge drives him to determine, in the room with a wall-mounted widescreen flat television and ‘widescreen’ windows, that his previously unknown intended victim murdered Sean. He decides he is not being set up, as this is the one discovery he believes could drive him to kill. Furiously he smashes Crow against the mirror. Agatha, screaming in empathy as an inscribed spectator, reminds him again, desperately, about free choice. Unlike every haloed suspect he, uniquely, aware of the minority report, possesses an alternative. There is no telling his response as zero approaches. The composition of him holding the gun is the obverse of its prediction; we looked through the screen then, or perhaps the scenario, or our relation to it, has subtly changed. He does not shoot. As the alarm sounds and the deadline passes, he arrests Crow and reads him his rights. A light behind Agatha creates the impression she is projecting the conversation as Crow reveals Anderton was indeed being manipulated towards killing him, before he grabs the gun and pulls the trigger, the shot propelling him through the plate glass window.

Light beams link the screen to Burgess’s face as he watches the television report of this apparent homicide. Shortly after, he kills Witwer, who has used projections to show discrepancies between Agatha’s and the other Pre-Cogs’ visions of Lively’s murder. Somewhat inconsistently, Agatha, taking refuge with Anderton and Lara at the latter’s house, projects verbally the future Sean would have had, in a scene imbued with ‘God Light’, even though she seemed unaware of Burgess killing Witwer. Again she demonstrates pre-cognition, sensing Pre-Crime too late, as they apprehend and halo Anderton.

The big sleep

The final twenty minutes ostensibly vindicate Spielberg’s sternest critics. Minority Report’s dystopian themes, retro-noir style and frustrated Oedipal challenge point to it being a downbeat adult movie in which the flawed hero becomes the fall guy – standard fare from The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946/1981) to The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) – yet Spielberg cannot let matters rest. Refusing this satisfactory, if dark, closure, he cranks the plot for another turn, as in A.I., resulting in a lengthy movie in which the final act gratuitously reverses all that precedes.

After Anderton’s incarceration, his estranged wife, transformed by Agatha’s projection of family contentment, visits Burgess. The old man’s dual nature, hitherto concealed, becomes apparent as we see him alongside his reflection. Nervousness reveals itself when he pricks his finger at Lara’s inquiry about Lively’s murder, and carelessly discloses knowledge of the method, arousing Lara’s suspicions.

Lara frees Anderton, using his eyeballs to gain entry and threatening Gideon with her husband’s gun. Incongruously perfunctory after all the previous complexities, this is also logically inconsistent. If Agatha is back in the Temple – reconfirmed when she later predicts Anderton’s murder – she would anticipate Gideon’s death, were Lara seriously prepared to use the gun. Without this warning, Gideon would know he was safe and would not cooperate. This is explicitly demonstrated, earlier, when Witwer deals calmly with a threat from Anderton – ‘Put the gun down, John; I don’t hear a red ball’ – becoming anxious only after the klaxon sounds.

There is a smack of adolescent self-righteousness in Burgess’s hubris being punished for betraying Anderton’s and the public’s trust and killing Agatha’s mother and Witwer. Changing from benign patriarch to obscene father – von Sydow’s performance recalls John Huston’s monstrous villain in

Chinatown (1974), and the actor had formerly starred as a kindly grandfather exposed as a former SS perpetrator of genocide in

Father (1990) – Burgess suffers humiliation and disgrace at a reception to celebrate his career. He is last to see Anderton’s screening of the murder. He shoots himself using the ornamented weapon presented at his retirement, an official recognition of his phallic potency – acknowledging his error and seeking Anderton’s forgiveness.

The screened murder evidences the deceit which predicated and now discredits Pre-Crime. Witwer’s paradox works through before the Jefferson Memorial, restoring American Justice. Witwer, who personified a younger Oedipal threat to Anderton’s authority, yet as agent of a more powerful department embodied the castrating power of the Father, is avenged, retrospectively, as a filial equal. Psychoanalytic convolutions – Witwer’s ambition derived from his policeman father’s murder when he was fifteen, while Anderton torments himself for having failed as a father, having lost his son – achieve instant resolution. ‘You see the dilemma?’ Anderton asks Burgess, while Agatha vicariously lives through the drama. ‘If you don’t kill me the Pre-Cogs were wrong and Pre-Crime is over. If you do kill me you go away. But it proves your system works. The Pre-Cogs were right.’

Burgess’s suicide exercises the free will his Clockwork Orange-like programme has denied others, and everything comes right in the kind of sickly sentimental Hollywood ending Spielberg’s detractors consider his stock in trade (Wilson 2003: 4; Felperin 2002; McDonald 2003). Anderton’s voice narrates Pre-Crime’s closure. He and Lara, pregnant, appear together, intimating the all-American family reconstituted, lit with rain shadows from the window to recall Anderton’s home-movie viewing and illustrate how wishes expressed then now become fulfilled. The Pre-Cogs, long-haired Romantics in hand-knitted sweaters and a golden glow, pass their days devouring books before an open fire. The camera cranes back to show them enclosed in a pastoral idyll in a quaint cottage on an otherwise deserted island, bathed in a beautiful sunset. Released during the aftermath of 9/11, when officials urged Americans to anticipate and prevent terrorist crime (James 2002: 15; Vest 2002: 108), the movie played its ideological role in asserting faith in the humane values of ordinary folks and distrusting shadowy state organisations, even while suspects were held in contravention of US civil law and international human rights agreements at Guantánamo Bay.

Yet all is not so simple. Following the clues that the ‘6’ outside where Anderton was supposed to murder Crow turned out to be a ‘9’ and the third man was an external billboard image, there is an alternative ending, a minority report so to speak, as befits a film that renders appearances deceptive, encourages close scrutiny and questions visual evidence. Just as

Jurassic Park ends with pterodactyl-like pelicans approaching the mainland, intimating the story’s continuance and making room for a sequel, as the sun hits the lens and Spielberg’s credit appears, so

Minority Report ends with a long – tenaciously long – shot of the tranquil scene, also a final inscription of the cinematic apparatus as the credits, starting with Spielberg’s, roll. This movie, comprising allusions to other movies, ends self-reflexively. As Jason Vest intriguingly suggests, the mise-en-scène of the last shot of the Pre-Cogs, ‘sitting in a loose circle … surrounded by water … reminds the thoughtful viewer of the circular water tank’ they inhabited (2002: 109). Vest’s point is that their difference leaves them detached from society. But a starker possibility remains: the tank is where they stay, while we see a fanciful sublimation of their true state. This is consistent with Vest’s conjecture that the last part of the film occurs within Anderton’s haloed head. Following Anderton’s wrongful arrest for murdering Crow and Witwer, necessary for Burgess’s cover-up, we see Agatha returned to the Temple; Gideon tells Anderton’s comatose figure: ‘It’s actually a kind of rush. They say you have visions. That your life flashes before your eyes. That all your dreams come true.’ The remainder of the film plays on Anderton’s mindscreen as he descends into darkness with a projector light above his head. The halo glows as a cut introduces Burgess declaring to Lara, ‘It’s all my fault!’

This movie that coalesced out of a shimmering primal scene finishes with Anderton, another Spielberg solipsist, positioned like Metz’s spectator in profound solitude (1975: 64). In relation to the spectator’s ego, Metz observes:

the question arises precisely of where it is during the projection of the film (the true primary identification, that of the mirror, forms the ego, but all other identifications presuppose, on the contrary, that it has been formed and can be ‘exchanged’ for the object or the fellow subject). Thus when I ‘recognise’ my like on the screen, and even more when I do not recognise it, where am I? Where is that someone who is capable of self-recognition when need be? (1975: 50)

Anderton in suspended animation, submitted to the Name of the Father, is Metz’s spectator: regressed prior to knowledge of loss, immersed and immobilised, subjected to reflections of his hopes and fears, desires and fantasies, reduced to illusory allseeingness and mastery that substitute for the emptiness of the position hollowed out for the self. Such fantasies can seem enormously realistic; witness the fine detail of an aircraft light sliding across the sky, maintaining continuity between shots, during the showdown between the symbolic Father and Son. Repeated penetrations of windows figure in a movie in which ‘reality’ is mediated on glass screens. Anderton, stacked in a jar, kicks the glass canopy out of a car he imagines himself trapped in and later outruns the Law in another that is entertainingly, if improbably, constructed around him, fully enclosing him. Underwater fantasies swirl around his unlikely evacuation of the Pre-Cog tank with Agatha. Images of blindness and eyelessness, one involving surgical apparatus that clamps the head like a Pre-Crime halo, return obsessively. But slips and logical inconsistencies, give the game away. Anderton’s capacity to remain immersed, associated with the moment of family destruction, is never utilised narratively in that when he hides from the ‘spyders’ in bath water he does reveal himself by exhaling. He is not blinded, as we are led to fear, when they shine beams in his eye. Sean’s tricycle, shiny-new, remains casually overturned in Lara’s yard – six years after his disappearance. Similarities between both Crow’s and Burgess’s killings, both, remarkably, suicides – although Anderton seemingly holds the gun both times – evince compulsive repetition, while another coincidence is the identical numbers on Crow’s hotel room and Anderton’s incarceration flask. Anderton’s apparent reunion with Lara could be memory rather than a jump forward in a film that repeatedly undercuts its own veracity.

In the final shot, the sun moves ninety degrees. As CGI begins with coordinates, the light source being fundamental, this appears unlikely to be technical error. Because the shot starts and ends, however, with the sun shining into camera – Spielberg’s equation of light with projective desire – and the movie questions and undermines subject positions, this is equally explicable as flawed, inconsistent, decentred narration, such as a dream. The imaginary lost object motivating Anderton’s narrative is no less than his life, a closed loop like a drawing of a clown somersaulting in a Zoetrope: following

A.I., a second feel-good ending that crumbles under scrutiny.