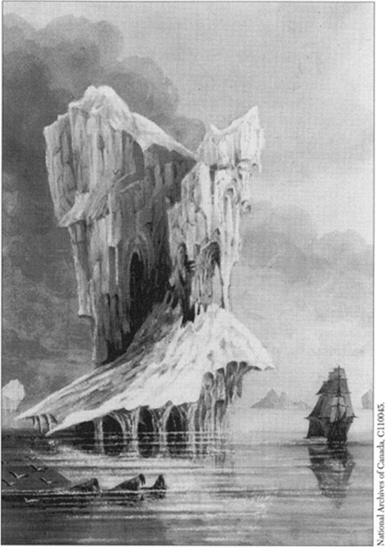

“The piece that had been disengaged at first wholly disappeared under water, and nothing was seen but a violent boiling of the sea and a shooting-up of clouds of spray.… After a short time, it raised its head full a hundred feet above the surface, with water pouring down from all parts of it, and then…after rocking about some minutes, it at length became settled.”

Lieutenant Beechey

describing an iceberg calving.

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was left with a surplus of ships and crews. Sailors were laid off, officers sent home on half pay, and ships decommissioned. It was a waste of years of training, but there was one area where this surplus could be usefully employed – exploration.

Two of the northern dangers Franklin encountered in 1818. An iceberg and some walrus in Hudson Strait.

In 1817, a well-respected whaling master, William Scoresby, returned from Baffin Bay to announce that the summer had been one of the most ice-free on record and that large areas of the Greenland coast, which were normally icebound all year, were open. The timing was perfect. Why not send idle ships and crews to discover something of this poorly understood corner of the globe?

The High Arctic was barely imaginable to the people of Franklin’s time. It was their equivalent of the moon – incredibly remote and inhospitable – and the explorers who went there were the Apollo astronauts of their day. It took determination and the latest technology to get explorers into the Arctic and keep them alive. To go there was to live life on the edge – and a narrow, slippery edge it was.

There were two incentives to send expeditions to the far North. The first was the lure of the fabled Northwest Passage, the shortcut to the riches of the Orient. Drake, Frobisher, Hudson, and Cook had all searched for it and failed. By the early nineteenth century, enough stories had been told about the North to make most merchants realize that there was no commercial route through the ice, but the magic of the myth still pulled people on.

The second incentive was scientific research: natural history in general, but, more specifically, magnetism. Terrestrial magnetism was poorly understood, yet it was essential to navigation between the territories of Britain’s far-flung and growing empire. The navy needed to know about it. They also needed to know about the aurora borealis, which was thought to be electrical in nature and related to magnetism. A raging debate was underway in scientific circles on the nature of natural electricity and magnetism. Exploration close to the magnetic pole, where the aurora was strong, held out the promise of answering some very basic questions.

Even in the popular imagination, electricity and magnetism loomed large. They were considered fundamental forces with a limitless potential and imbued with almost supernatural powers. After all, hadn’t it been these very forces which had animated the monster’s dead tissue in Mary Shelley’s immensely popular story, Frankenstein?

In 1818, Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, and John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, succeeded in persuading the government to mount two Arctic expeditions. The ambitious nature of both merely indicated how little people at that time knew about conditions in the Arctic.

One expedition was charged with sailing through the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. The fact that some of the greatest explorers in history had failed abysmally to do this over the previous three hundred years did not discourage anyone. The second expedition was even more ambitious and unrealistic. It called for a ship to sail straight north, discover the North Pole, continue on through the Bering Strait, and eventually reach the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii).

The Northwest Passage venture was led by John Ross and had Edward Parry as second-in-command. They mapped the west coast of Greenland and the east coast of Arctic Canada. Unfortunately, the expedition is mainly remembered for discovering a range of nonexistent mountains which Ross believed blocked Lancaster Sound. In reality, Lancaster Sound is the entrance to the Northwest Passage, a fact that Parry suspected despite his commander’s opinions.

The Polar expedition was commanded by David Buchan, who had been the first European to make contact with the First Nations of Newfoundland. Second-in-command was Lieutenant John Franklin. Buchan commanded the whaler Dorothea with twelve officers and forty-three crew. Franklin’s first command was the Trent, a smaller whaler with ten officers and twenty-eight crew.

Franklin’s motives in becoming an explorer were not entirely a pursuit of adventure. One way for a half-pay officer to advance his career in the inactive years after 1815 was through exploration. When Franklin applied for the job of Buchan’s second-in-command, he expressed concern that he might return with his health shattered after an expedition of perhaps five or six years. Patrons and friends with influence might have moved or died and all this would hurt his chances of promotion. Therefore he asked, “I should hope, were an offer ever made to me, it would be accompanied by a promotion.”

An offer was made – without any guarantee of promotion. Despite that, Franklin jumped at the chance. The appeal of escaping the boredom of inactivity was too great.

The expeditions aroused considerable interest, and the number of visitors to the ships was so high that it hampered preparations. Many of the visitors were men of science, eager to discuss their pet theories of the unknown North with the ship’s officers. Franklin was not much help. He thought it ridiculous that he had to talk to these experts considering “how little I know of the matters which usually form the subject of their conversations.”

However, one visitor caught Franklins attention. Eleanor Ann Porden was only nineteen, yet already she was quite outspoken for a young lady of that time. She had a keen interest in science, which explains her visit, and she had some pretensions to being a poet. Despite having little in common, the pair impressed each other.

Franklin’s first venture into the Arctic began on April 25, 1818. Oddly, exactly thirty years later, this date would be significant to the survivors of Franklin’s last visit to the North. Almost as soon as they set sail, the crews discovered that the quality of ships given to exploring parties had not improved since Flinders’ voyage. The Trent had several leaks. The crew patched some of these at the Orkney Islands, but the worst one eluded detection, and so the pumps had to be manned every watch.

At Spitzbergen, north of Norway, the expedition found its way blocked by heavy ice. There they met some Russian hunters who were collecting walrus skins and tusks. The walrus were so numerous and so aggressive that they attacked and almost destroyed one of the Trent’s longboats during a hunting expedition. The large beasts rushed the boat in a mass, hitting it with their tusks or butting it with their heads. Harpoons and axes merely slid off the animals’ thick hides. It could have been a disaster, but one man managed to load his musket in the wildly swaying boat and fire it at the largest walrus, which appeared to be leading the attack. Immediately, the others stopped the assault and swam off, dragging the body of their leader with them.

As the expedition waited for the ice to break up, Franklin kept busy mapping and exploring the area. Numerous glaciers calved into Magdalena Bay where the ships were anchored. No one was really familiar with this phenomenon and they examined it closely. Unfortunately, they were also not familiar with the consequences of calving.

With Franklin in command, a group of men set out in a launch to examine the end of the bay. All at once, the men heard a report as loud as a cannon from above their heads. Looking up, Franklin watched in horror as a huge piece of ice, sixty-one metres above them, broke away from the face of the glacier and plunged down. The men frantically rowed to keep the boat pointed towards the immense wave they knew was coming, and watched as the iceberg crashed into the sea with a noise clearly heard on the Dorothea, six kilometres away.

As their small boat was thrown around like a cork by the wave, Franklin knew they would be lucky to survive. When things calmed down, they approached the iceberg and measured it: it was eighteen metres high, 400 metres around, and about 426,720 tonnes in weight.

Buchan attempted several times to lead his expedition north, but they were met each time by a vast impenetrable wall of ice. On one occasion, they were trapped for two weeks, on another, three weeks. While they were forced to remain idle, the crew of the Trent did manage to discover the leak that had so bothered them on the voyage north – it had been caused by a bolt which a shipyard worker had forgotten to install.

When open water appeared and leads seemed to offer a way through the ice, the two small vessels sailed in. Invariably, the leads closed and the ships became beset. Then the crews had to take to the ice, laboriously cut holes ahead of the ships, and physically pull them forward. It was gruelling work, and often the small distance they managed to drag the ships was cancelled out by the drift of the ice in the opposite direction when they were held fast.

On one occasion, the pressure of the ice was so great that it lifted the ships up and twisted the hulls. Men watched helplessly as doors flew open and the timbers cracked deafeningly around them. Another time, they were caught in a gale close to the coast of Spitzbergen. The wind was driving them onto the rocky coast and certain destruction. Buchan decided that their only hope lay in sailing directly into the loose pack ice, where huge blocks of ice were being thrown around by the wind and waves. It was terrifying, for these loose blocks of ice could easily stave in the sides of the ships. Franklin took what precautions he could. He ordered the men to hang cables and iron plates over the sides to protect the hull. He had everything movable tied down and the masts strengthened.

Even so, the shock of sailing into the ice almost broke the Trent’s masts. Ice floes twice the size of the ship ground against her hull with a rending noise. All around the tiny vessels, the ice and waves rose and fell in a terrifying scene. Through the overwhelming noise the crew could hear the continuous mournful tolling of the ship’s bell.

After hours of this punishment, the gale abated and the expedition escaped to open water to assess the damage. Ice had so broken in the side of the Dorothea that her crew wondered how she had survived. Obviously she could not continue exploring. Franklin wanted to continue with the Trent, but the Dorothea was so badly damaged that it was doubtful she could even make it back to England, and so the Trent was forced to accompany her to render assistance if needed. Apparently, the open ice conditions that Scoresby had reported in 1817 had simply been a temporary condition. A very similar, variable weather pattern thirty years in the future would lure an overconfident Franklin and his ships to their doom.

The ships’ carpenters did their best to repair the Dorothea and the Trent in preparation for the voyage home. The officers took magnetic observations and carefully surveyed the coast. On August 30, the expedition set sail and on October 22, 1818, arrived back in London.

Geographically, Buchan’s Polar expedition achieved little; certainly it came nowhere close to the optimistic expectations. However, it gave Franklin his first taste of the Arctic and a glimpse of the violence and dangers of ice and climate in the northern lands.The expedition also marked the opening of the golden age of British Arctic exploration. Over the next forty-one years, dozens of explorers would outline the map of the Canadian Arctic, unravel the mystery of the Northwest Passage, and dispel many of the myths of the North. In a sense, Franklin’s journey bracketed this period. He was on the first Arctic foray, and the golden age ended when Francis Leopold McClintock returned to Britain in 1859 with conclusive news of the ultimate fate of John Franklin’s last expedition.

After Buchan and Ross returned, the navy moved rapidly to build on what meagre results the two expeditions had brought back. Attention moved away from the Pole – there was obviously no way through there – and settled firmly on the Northwest Passage. Here the British could fill in a huge blank area on the map, describe countless new species of animals and plants, and measure the mysterious magnetic phenomena.

The navy planned another dual attack. One route was obvious. Parry had come back expressing doubts about his commander’s conclusion that Lancaster Sound was a dead end. That needed to be checked out, and Parry was given command this time. But what of the other expedition, now that the Pole had proved unattainable? What about an overland assault through the Canadian wilderness to the Arctic coast? That appeared to offer promise, and Samuel Hearne and Alexander Mackenzie had proved it was possible. For some unrecorded reason, the navy overlooked Buchan as leader, and offered command of the overland expedition to John Franklin.

The year 1818 marked the end of Franklin’s apprenticeship. He was thirty-two years old, and he had a wealth of experience in both exploration and battle. He had proved himself calm in a crisis, and he was a popular leader. He had developed some strong navigational skills, he was a thorough observer with an interest in scientific inquiry, and he stood out from the horde of unemployed naval officers around him. He had challenged the Arctic and it was calling him back. John Franklin was ready to lead an expedition into unknown territory. He was about to begin the fabled quest for the Northwest Passage with which his name would be associated forever.

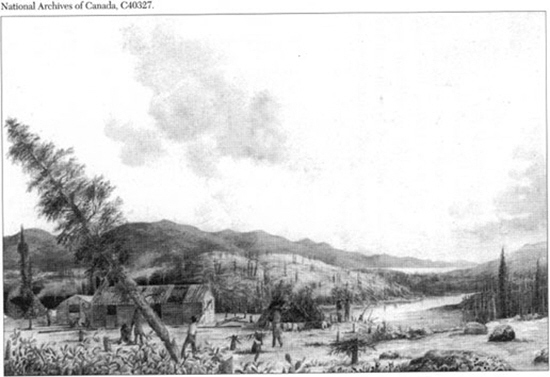

The Place Where Franklin’s journey almost ended. Fort Enterprise under construction, 1820.