The most obvious difference between airborne units and conventional infantry was the use of air transport to deliver the units into combat. This had important implications in their combat mission. In order to be air transportable, airborne infantry were invariably lighter armed than comparable infantry units and had much more limited logistical support. Since the airborne units would be landed at some depth behind enemy lines and fight in isolation for some time, these factors strongly shaped the missions assigned to airborne divisions. The role of these formations was envisioned as complete commitment by air, seizure of essential but limited objectives and quick relief by juncture with the associated main ground effort.

As a result of these factors, several missions were seen as particularly suitable for airborne operations, with two being the primary missions. The first mission was to seize, hold or otherwise exploit important tactical locations in conjunction with, or pending the arrival of, other forces. This was the primary mission executed by airborne divisions on D-Day in Normandy, Operation Dragoon in southern France in August 1944 and Operation Market in the Netherlands in September 1944. The second major mission envisioned for the airborne divisions was to attack the enemy rear and assist a breakthrough or landing by the main force. This mission was part of the assignment of the US airborne divisions on D-Day, but better describes the main mission of Operation Varsity in March 1945. There were several other missions envisioned for airborne divisions, some of which were subsidiary objectives for the operations conducted in 1944–45. At least four were outlined in various field manuals: to block or delay enemy reserves by capturing and holding key terrain features; to capture or destroy vital enemy installations thereby disrupting his system of command, communications and supply; to capture enemy airfields; and to delay a retreating enemy force.

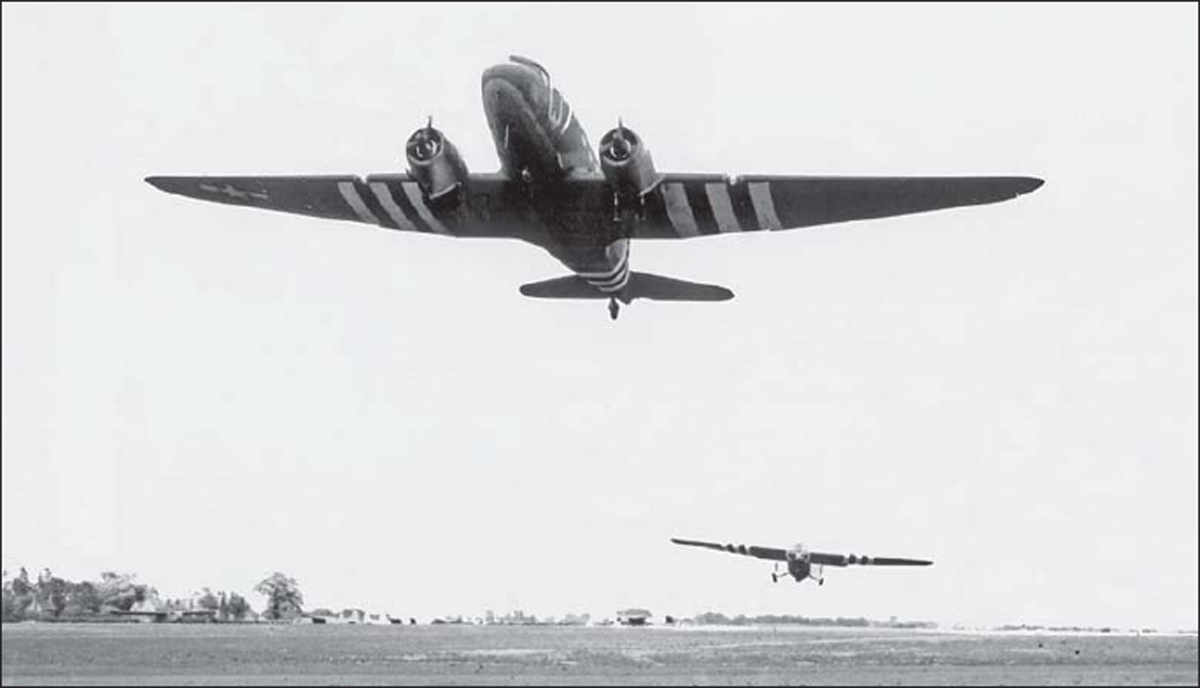

The German use of gliders at Eben Emael and Crete encouraged US development of this capability. This is a C-47 of the 90th TCS, 438th Troop Carrier Group, towing aloft a Horsa glider from Greenham Common on D-Day, June 6, 1944. (NARA)

Due to their dependence on air transport, air-landing tactics were unique to airborne infantry doctrine. One of the major issues in planning airborne missions was the matter of nighttime versus daytime drops. The US Army initially favored nighttime missions since it was presumed that the cover of darkness would shield the airborne landing at its most vulnerable moment. However, in practice, the difficulty of landing an airborne force with any precision led to a shift in policy after Normandy that restricted airborne operations to daylight missions to prevent the excessive dispersion of forces. Weather posed a similar dilemma to airborne forces. Due to the inadequacy of radio-electronic navigation aids in 1944–45, some degree of visual navigation was essential for both the troop transport pilots and the glider pilots. As a result, airborne missions were invariably limited by the weather to relatively clear days, or days where the cloud cover was high enough to permit the air trains to fly under it.

In spite of these distinct limitations, airborne missions possessed some significant advantages. Their most important asset was surprise. An airborne drop could take place anywhere, at any time, forcing the Germans to divert forces to defend against the vertical threat. For example, the threat of airborne attack forced the Germans to fortify the landward sides of key ports along the English Channel for fear they could be rapidly seized by a surprise airborne assault. Airborne missions could use the leverage provided by air delivery to avoid the strongest enemy defenses and attack the enemy where weakest, greatly amplifying the combat power of these otherwise lightly armed units.

On the other hand, airborne divisions had distinct limitations compared to conventional infantry divisions. Their infantry regiments were generally smaller, especially in regards to supporting weapons. Since their artillery had to be delivered by air, it was invariably less powerful—the 75mm pack howitzer versus the 105mm howitzer in the conventional divisions. Logistical support was minimal so the division could only fight for a few days before needing substantial reinforcement.

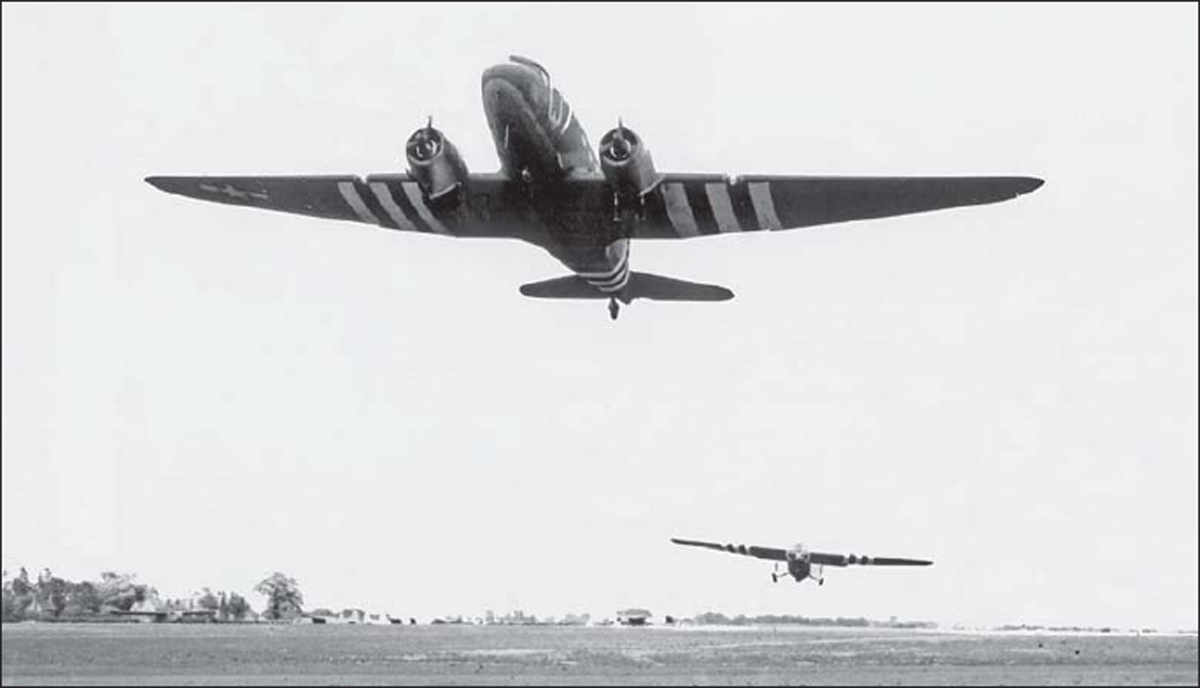

Since airborne divisions would often fight behind enemy lines, the capability to re-supply from the air was essential. This is a re-supply mission flown to the 101st Airborne Division in Bastogne by the 73rd Troop Carrier Squadron, 434th TCG, in December 1944. (NARA)