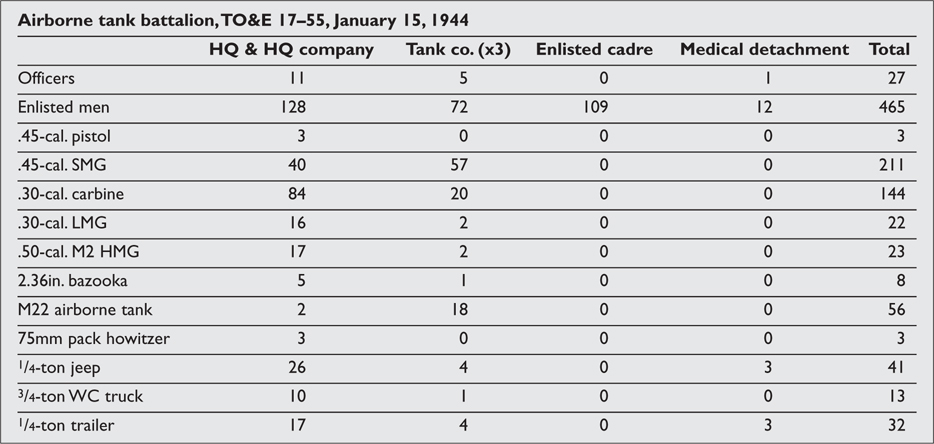

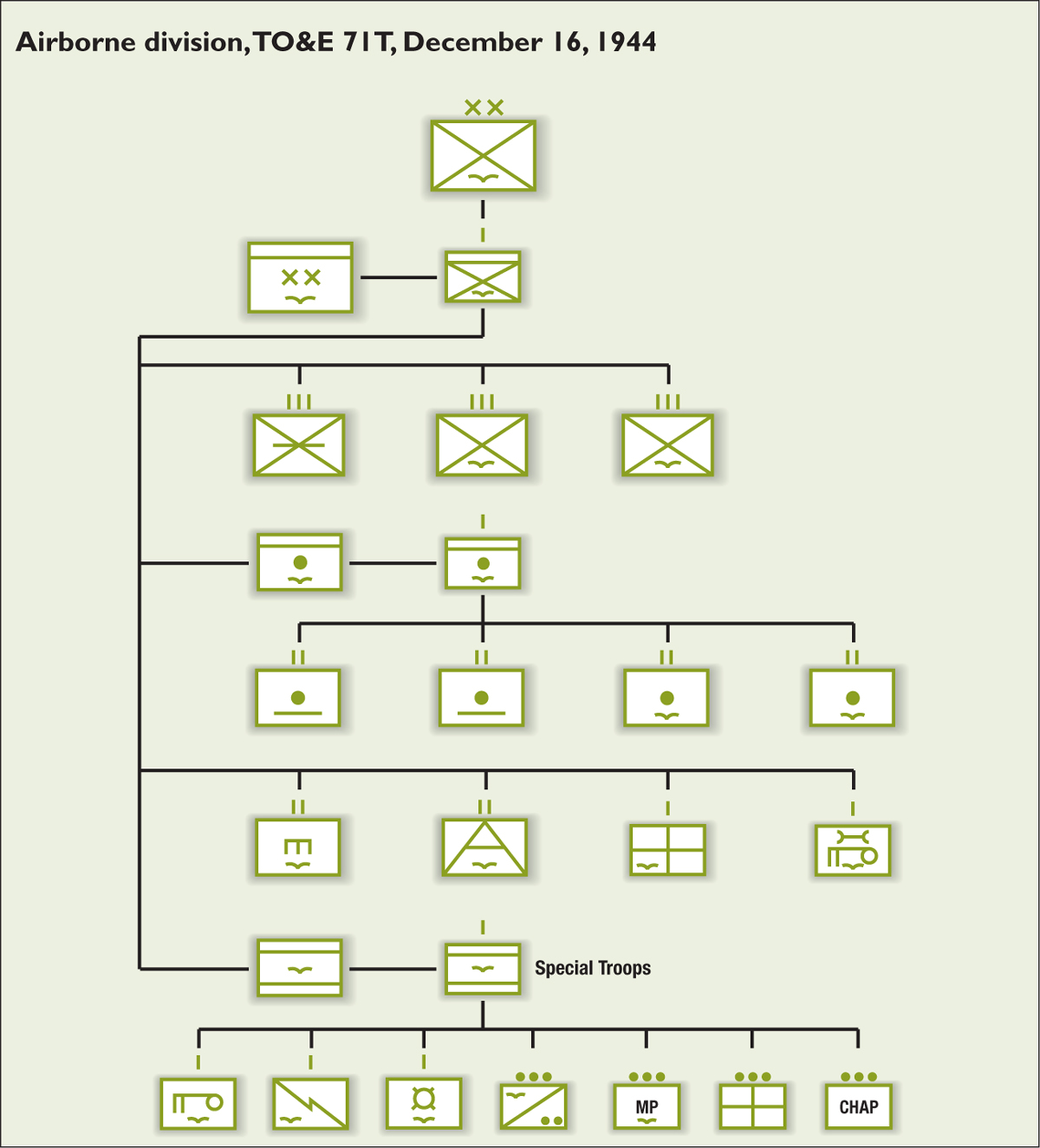

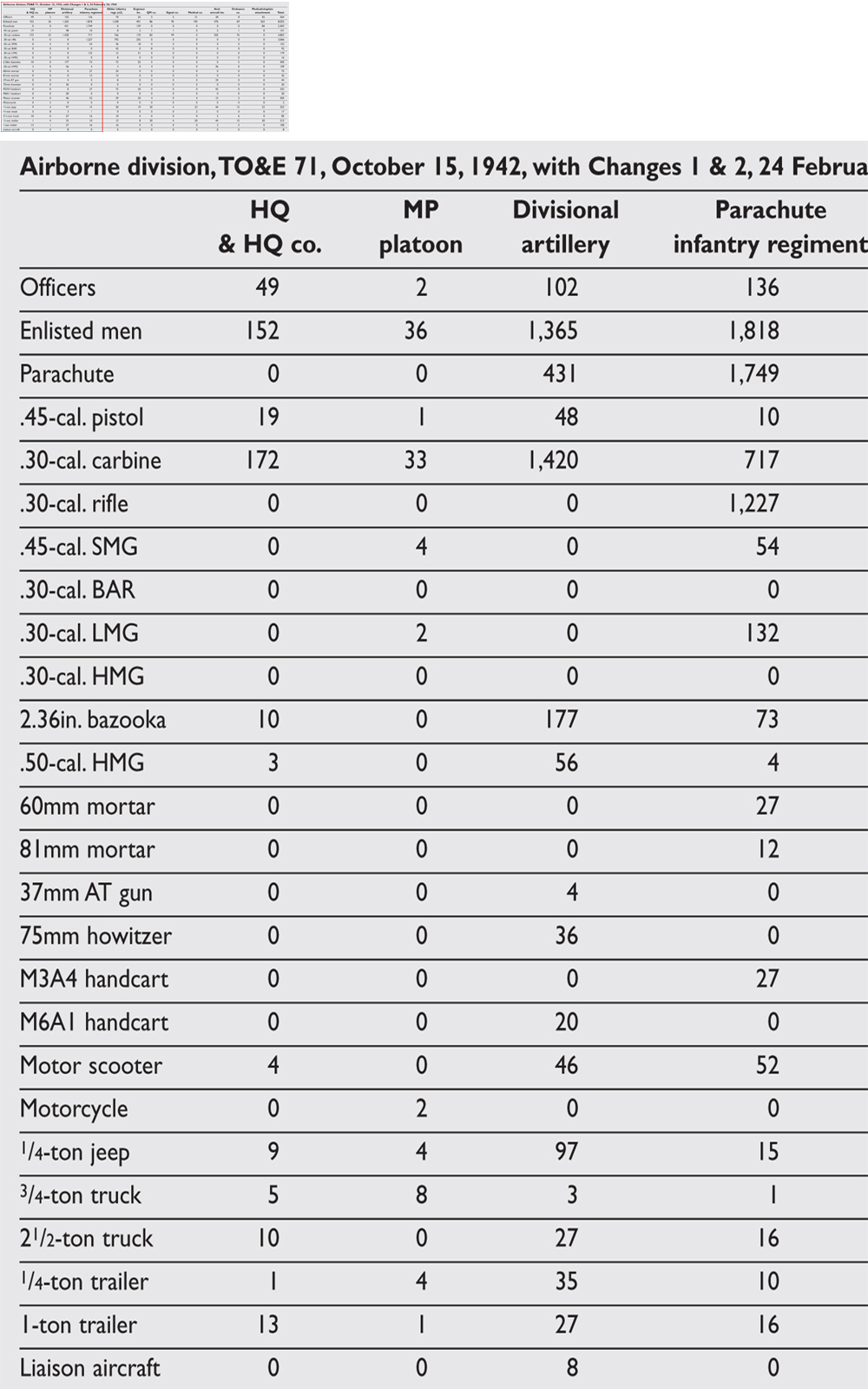

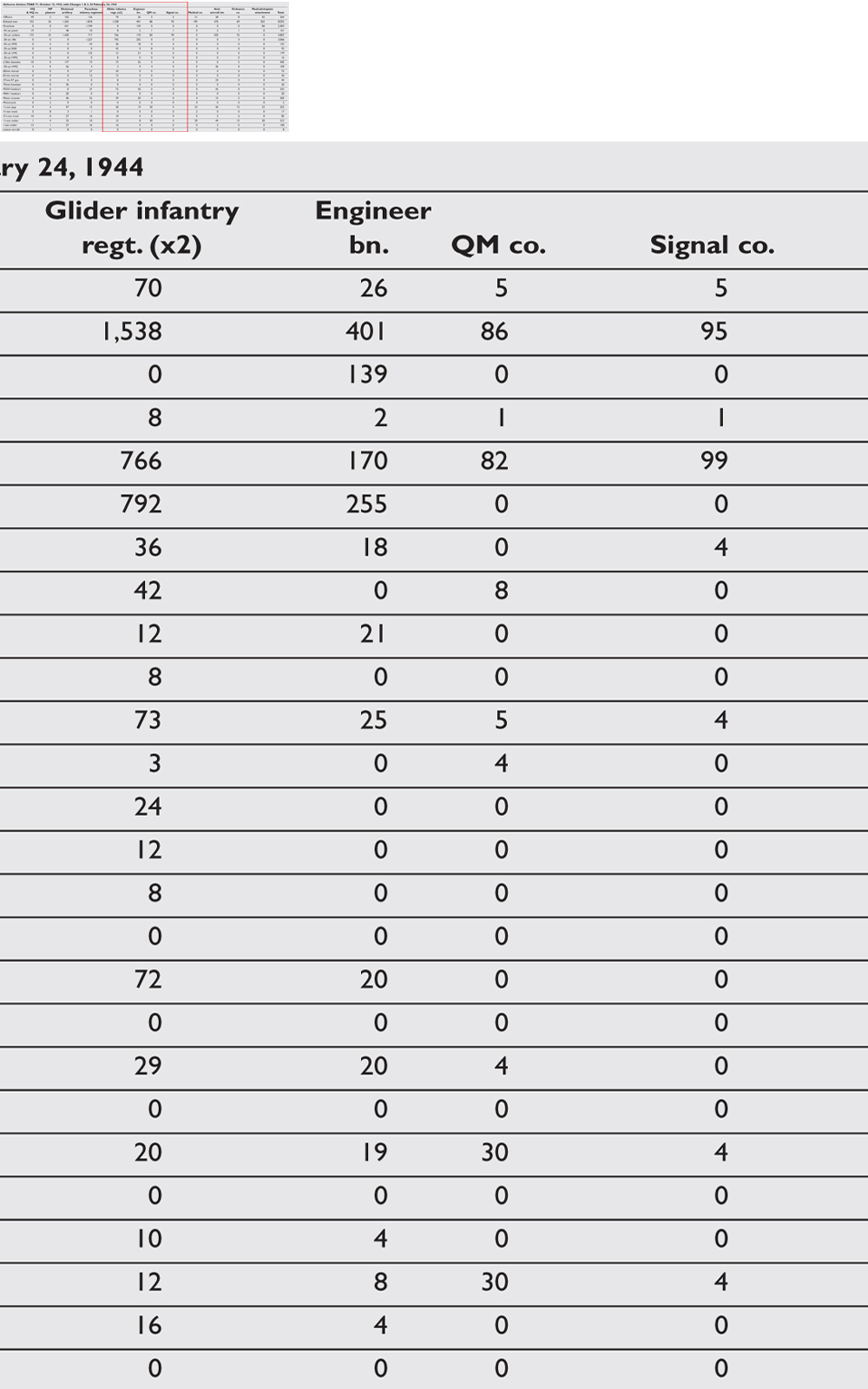

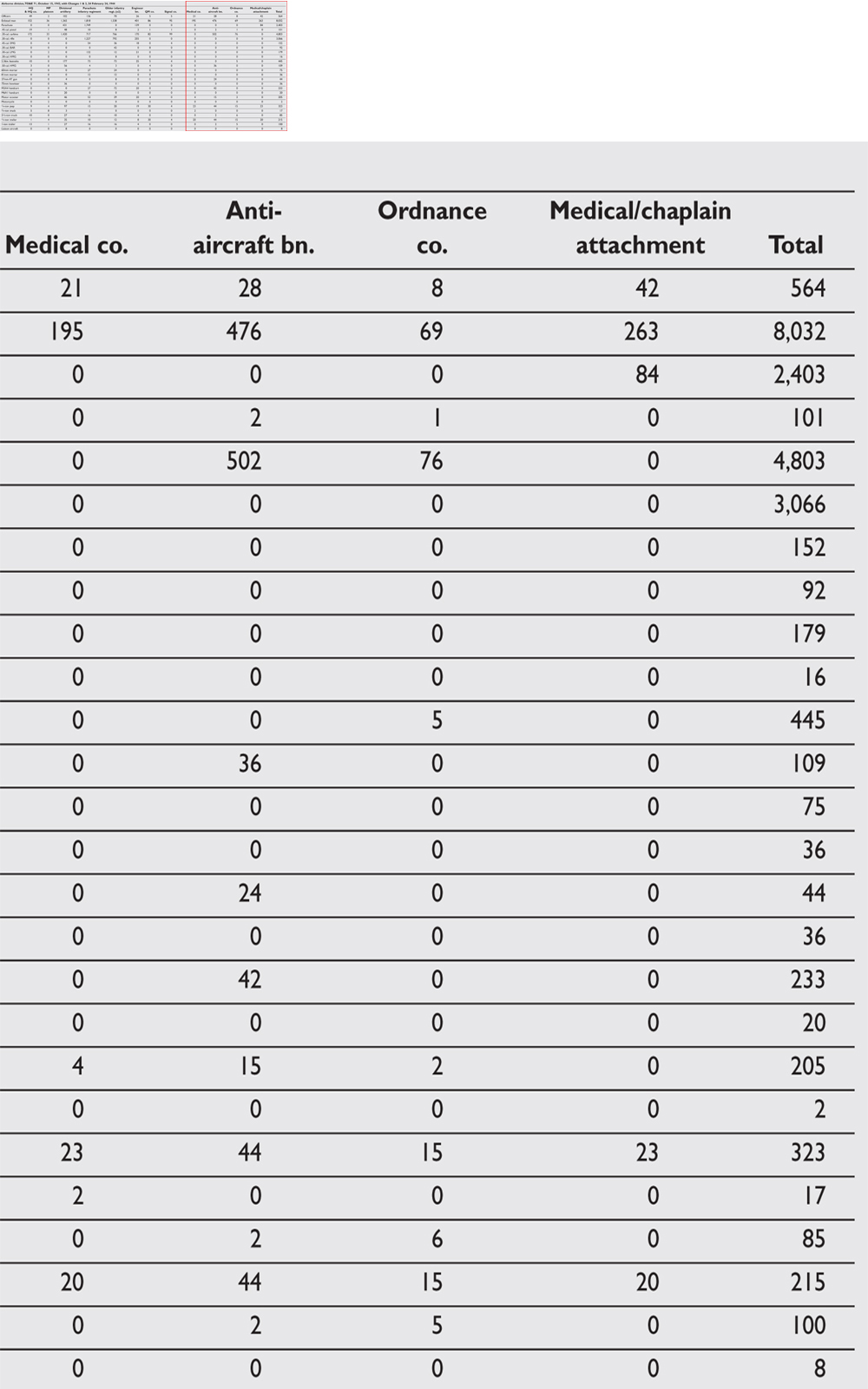

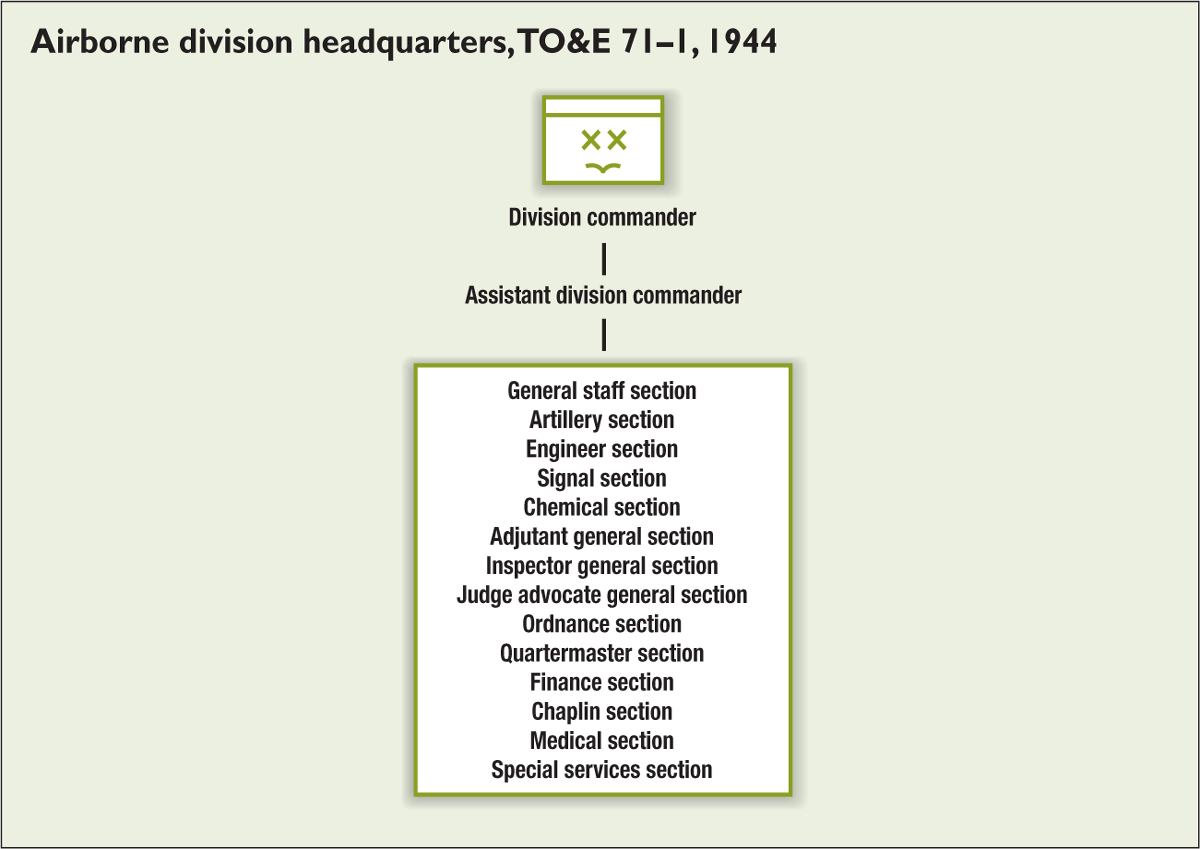

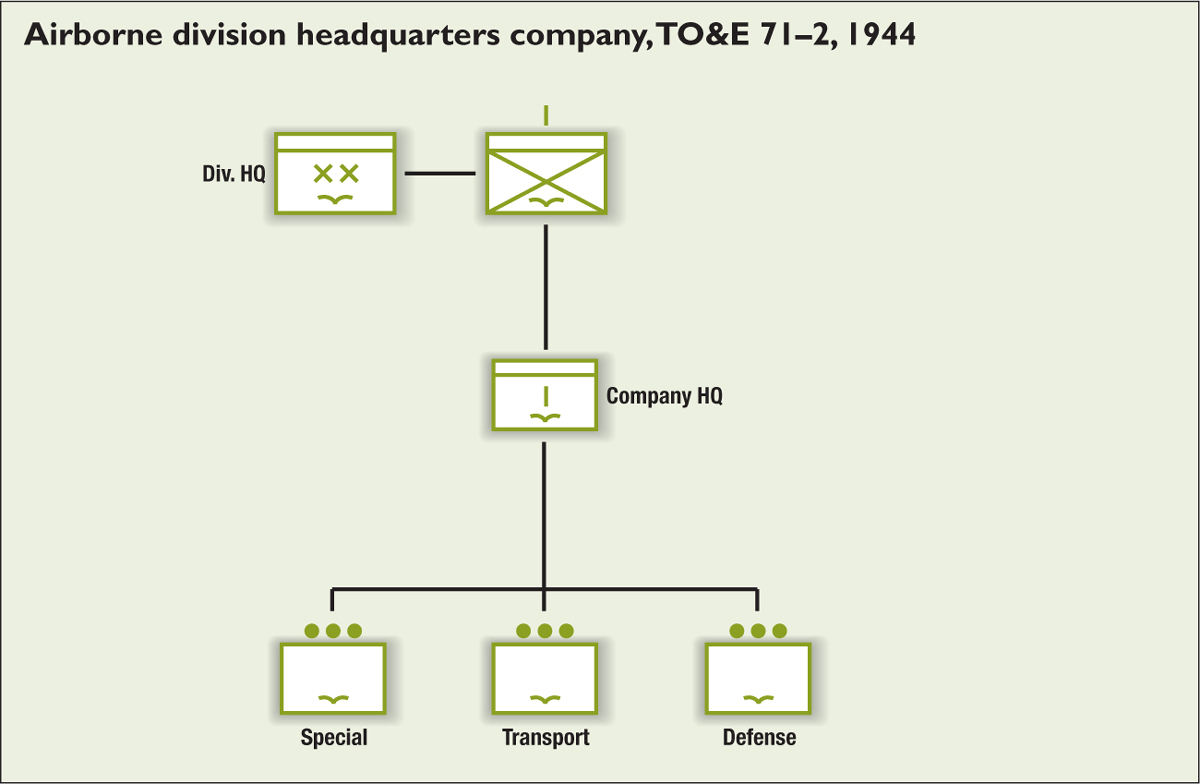

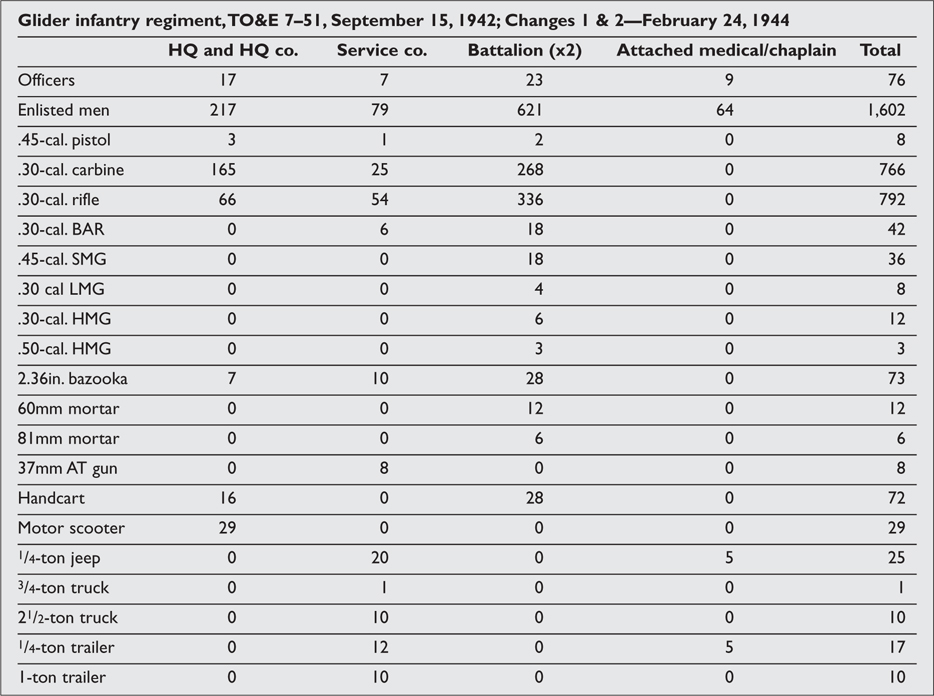

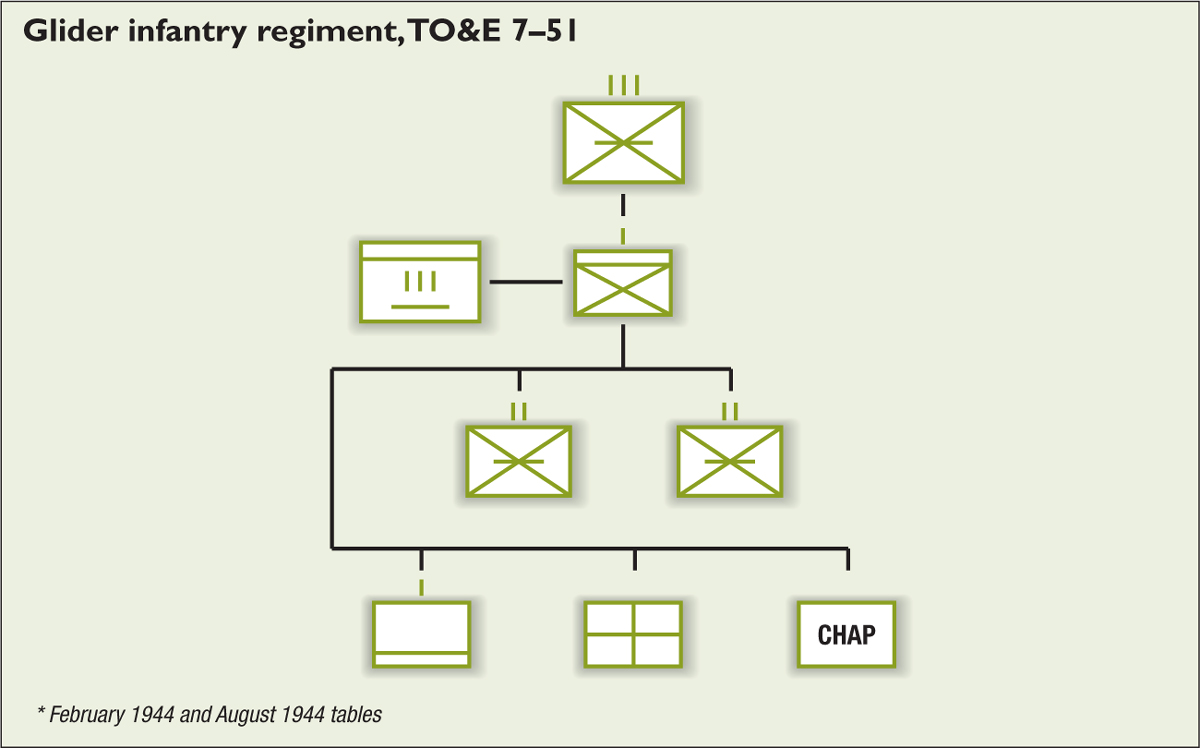

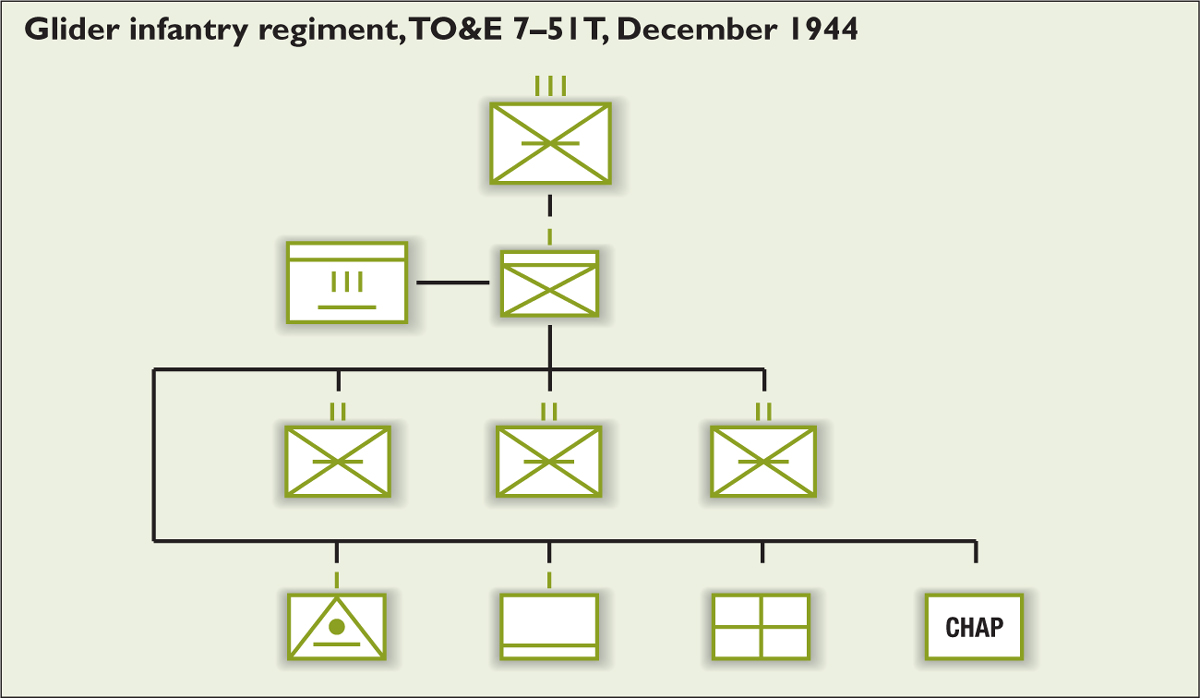

The US Army airborne divisions were originally organized under the October 1942 table of organization (TO&E) around two glider infantry regiments and one parachute infantry regiment. Two changes were instituted to this table in October 1943 and February 1944, and the table shown on page 18 is based on the February 24, 1944, version that was in effect at the time of D-Day. The divisional organization was heavily influenced by the preferences of the chief of the AGF, Gen. Lesley McNair, who favored the smallest organization possible to make it easier to ship the units overseas. McNair preferred to add capabilities to an austere divisional structure by overseas attachments rather than incorporate them as organic elements of the divisional tables. However, this tendency often got carried away. So for example, the glider infantry regiment had only two battalions, instead of the triangular organization elsewhere in the infantry, causing tactical problems. The skimpy organization also was based on the false presumption that War Department doctrine would be followed and that airborne divisions would be relieved a few days after landing. In practice, it was difficult to extract a high-value combat formation from the midst of battle across crowded lines of communication, and the airborne divisions invariably fought for weeks rather than days before relief. This skeletal structure proved so troublesome under actual combat conditions that there were continual efforts to circumvent the tables of organization and add assets.

The rifleman’s standard weapon in the airborne was the same as in the regular infantry, the M1 Garand rifle. This is Lt. Kelso Horne, leader of the 1st Platoon, Co. I, 508th PIR of the 82nd Airborne Division near St. Saveur-le-Vicomte in mid-June after the Normandy landings. (NARA)

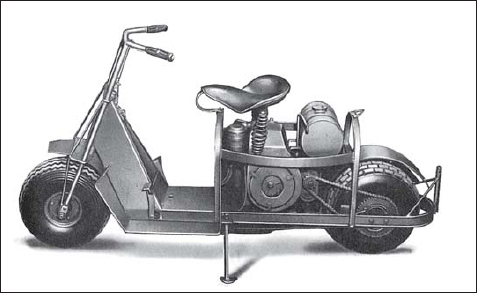

In comparison to regular infantry regiments, the airborne regiments in June 1944 had fewer troops and weapons, and were roughly half the size. Due to the limitations of air delivery, the divisional structure was considerably more austere than a comparable infantry division, with significantly less artillery firepower and a much more skeletal logistical infrastructure. The infantry division had three 105mm howitzer battalions for direct support and one 155mm howitzer battalion for general support while the airborne division had three 75mm pack howitzer battalions, one delivered by parachute and two by glider. Although the airborne division was authorized a modest number of trucks for supply, these could not be delivered by air and so were only available at base, or during prolonged ground operations. The only vehicle other than motor scooters that could be air delivered was the ¼-ton truck (jeep), which was the mainstay of the airborne division for tactical requirements. In place of trucks, the units were issued with handcarts to assist in moving ammunition and supplies. Some tactical units were omitted and the division lacked a reconnaissance element and a military police formation, which forced the diversion of airborne infantry to take on these functions in the combat zone.

The standard sidearm in the airborne was a folding-stock version of the M1A1 .30-cal. carbine. (MHI)

Airborne troops carried as much ammunition and supplies as was practical as seen here with a paratrooper armed with an M1A1 Thompson .45-cal. sub-machine gun with numerous extra magazines after a practice jump in France in February 1945. (MHI)

The divisional organization was especially bare in regards to administrative and support personnel. It lacked an organic parachute maintenance capability, which became more noticeable once deployed overseas than when the divisions were stationed in the US. Its small allotment of tactical vehicles adversely affected training and administration of the division when not in combat. To make up for these shortfalls, airborne divisions tended to have an abnormally large number of attachments when the division was involved in prolonged ground combat. These are detailed below in the “Unit status” section where the key attachments in several of the major operations are listed. However, corps commanders during the war were not happy with this arrangement as it drained the corps of combat battalions and support units needed for corps operations. In addition, corps commanders frequently complained that the airborne divisions did not make best use of attached combat units such as tank battalions as they had generally not trained with such units and were unfamiliar with their tactical employment. They were also critical of the airborne divisions’ lack of skill in using attached quartermaster truck units, once again due to their unfamiliarity with standard infantry practices. The use of attachments rather than organic components proved to be a poor concept and was abandoned after the war. The changes in the divisional tables through 1944 tried to add a minimum number of formations to clear up the worst of the problems.

Besides the jeep, the only other motor vehicle delivered during airdrops in any number was the airborne motor scooter. This example is the standard Cushman Model 53, weighing 260lb with a 5hp engine. The US Army acquired a total of 4,734 in 1944–45 primarily for airborne use. (MHI)

Troops of the 101st Airborne Division move down a road in Normandy following the airdrops. The small number of tactical vehicles in the division obliged airborne units to employ handcarts to move supplies and ammunition as seen here. (NARA)

The actual airborne divisional structure was much less rigid than the regular infantry divisions due to the novelty of the doctrine and its basic immaturity. Improvements were continually taking place, many of them outside the table of organization. Prior to Operation Husky on Sicily, the 82nd Airborne Division had adopted a mix of two parachute and one glider infantry regiments due to shortages of gliders. This mix remained the preferred divisional configuration in spite of the tables of organization. Prior to the Normandy landings, the 82nd Airborne Division’s 504th PIR was committed to the Anzio operation in Italy and was unable to rejoin the division in time for Normandy. In January, the division was allotted the 507th and 508th PIR, which were added to the veteran 505th PIR and the 325th GIR, giving the division a four-regiment structure with a preponderance of parachute regiments instead of the intended glider-heavy configuration. As a result, the 82nd Airborne Division also had four artillery battalions instead of the usual three. Furthermore, the glider infantry regiment was reinforced with another battalion to conform to the US Army’s doctrinal preference for a triangular regiment instead of the two-battalion organization called for under the existing table. Likewise, the 101st Airborne shifted to a mix favoring parachute regiments, adding the 506th PIR and attaching the 501st PIR in addition to its 502nd PIR and 327th GIR, and also receiving a third battalion for its glider infantry regiment. There were also numerous changes from the table of equipment. For example, the February 1944 table authorized the use of the obsolete 37mm anti-tank gun as the division’s only anti-tank artillery since the standard infantry division weapon, the 57mm gun, was too heavy. However, prior to D-Day, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were both able to obtain the lighter British airborne 6-pdr, which was substituted for the 37mm gun in Normandy. The divisions also attempted to improve their artillery firepower by substituting the M3 105mm howitzer for the 75mm pack howitzer in one field artillery battalion, which took place prior to the Normandy landings even though not officially authorized.

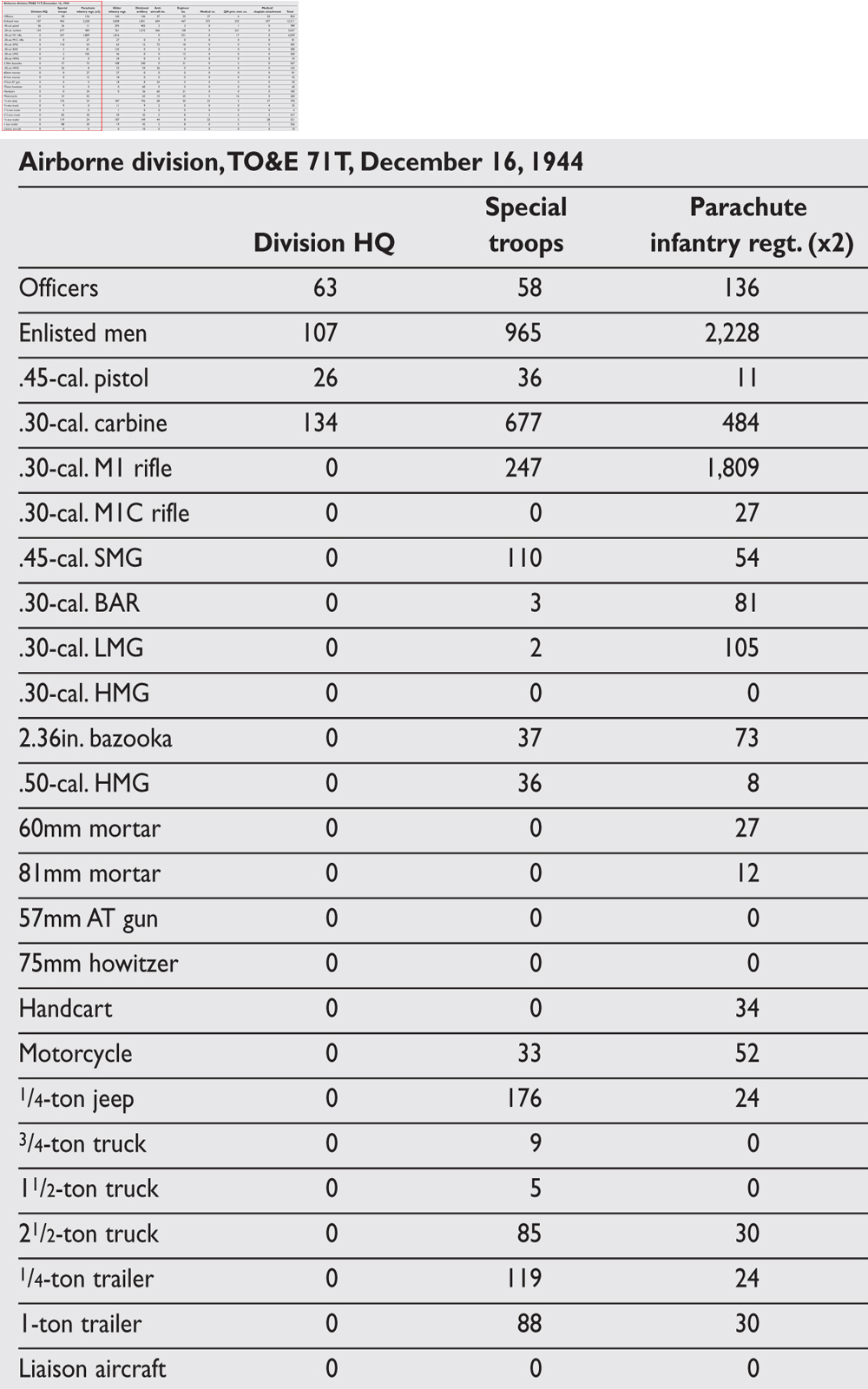

The August 1944 TO&E made very modest changes to the division, for example adding a parachute maintenance company. The first major reorganization occurred under the December 1944 table, in large measure due to the Army chief-of-staff Gen. George C. Marshall insisting that the airborne division commanders’ views be taken into account. Gen. Maxwell Taylor of the 101st Airborne Division was flown to Washington specifically for this purpose, the reason he was not in command of the division when it was abruptly trucked to Bastogne on December 19, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge. The December 1944 reorganization finally institutionalized the shift to two parachute infantry regiments and one glider infantry regiment, and a significant increase in equipment and personnel. It also codified practices that had already taken place, such as the addition of a third battalion to the glider infantry regiment. The division’s various support elements were consolidated under divisional special troops, which included a military police platoon, recon platoon, ordnance company, quartermaster company and signal company. The early tables had been much too austere in providing rear area administrative units, and the December 1944 tables attempted to rectify this situation by strengthening the support elements as well as the combat elements. The divisions in the ETO reorganized under this table in February–March 1945.

Even after the December 1944 additions, the airborne division still had problems. A postwar study of divisional organization by the General Board concluded:

The airborne division has worked under several handicaps which limited the missions to which it could be assigned with expectation of complete success. It has very little transportation and is in effect a foot division once on the ground. Its artillery is light and engineer construction equipment is practically nil. Higher headquarters have always had to attach many extra units to the airborne division in order that it might keep up with the others … The results obtained by attaching extra troops to an airborne division were not as good as they would have been had these troops been organically part of the division.

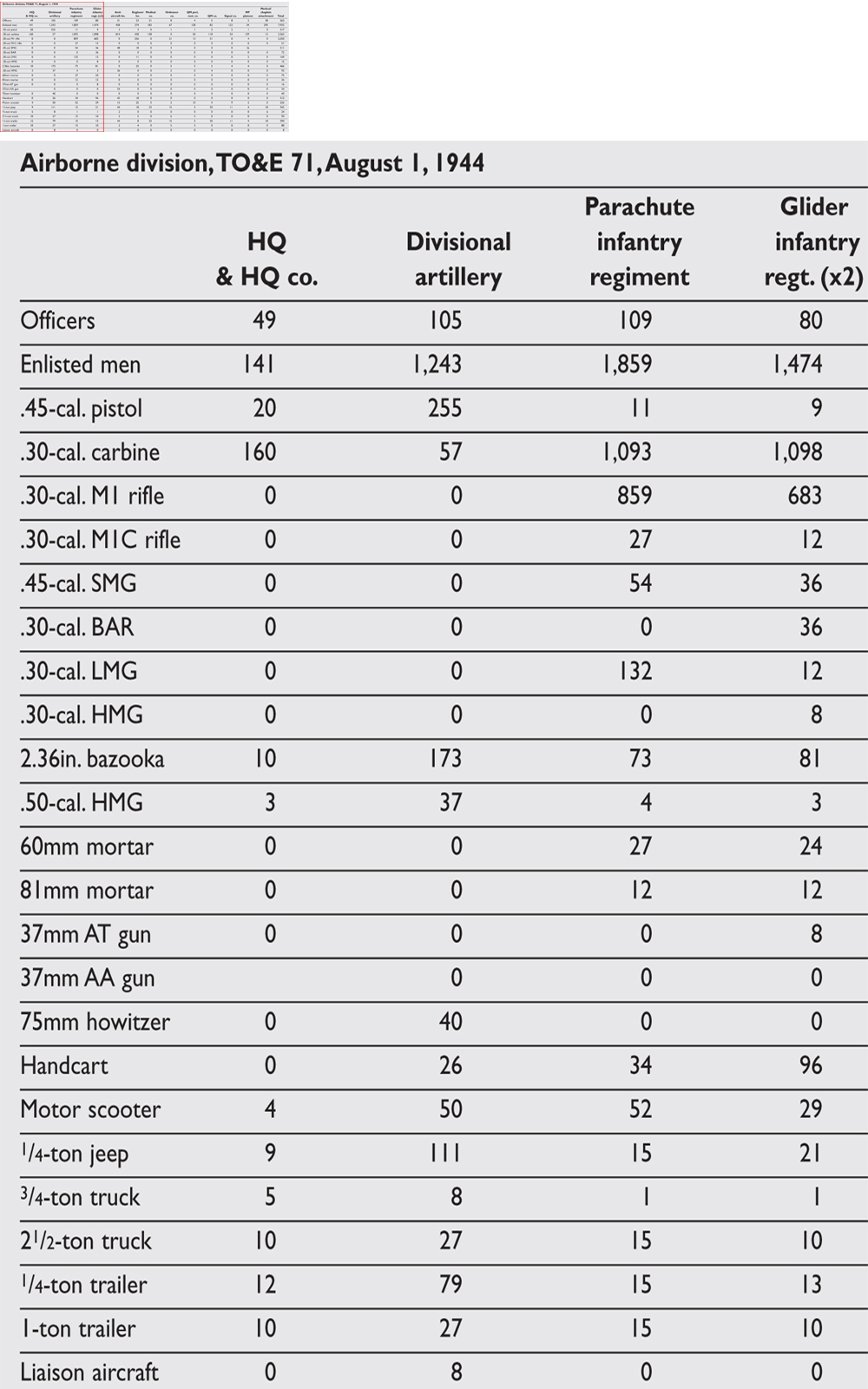

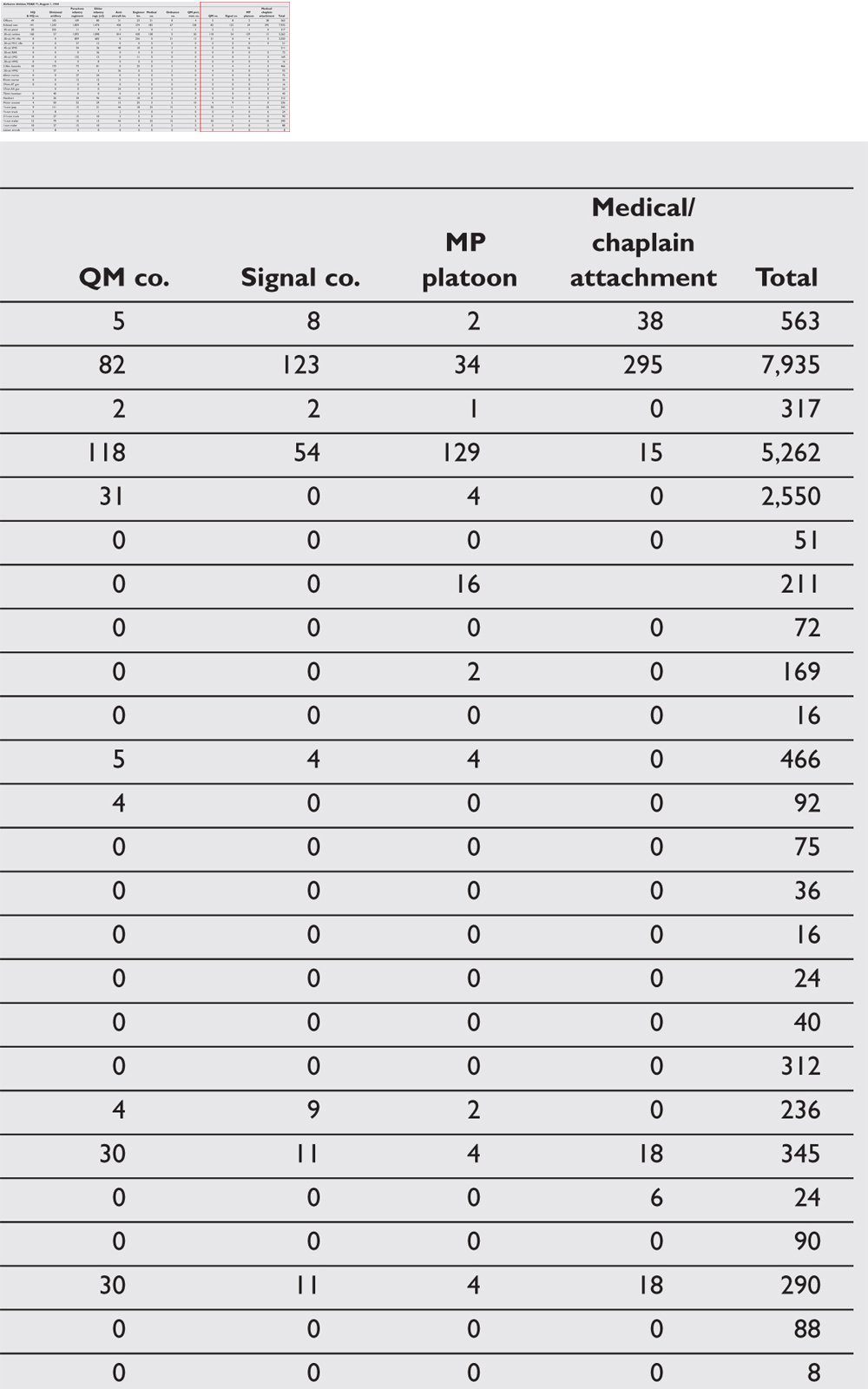

| Comparison of airborne division tables 1944 | |||

| Feb 24, 44 | Aug 1, 44 | Dec 16, 44 | |

| Officers | 564 | 563 | 824 |

| Enlisted men | 8,032 | 7,935 | 12,211 |

| .45-cal. pistol | 101 | 317 | 789 |

| .30-cal. carbine | 4,803 | 5,262 | 5,037 |

| .30-cal. M1 rifle | 3,066 | 2,550 | 6,049 |

| .30-cal. M1C rifle | 0 | 51 | 81 |

| .45-cal. SMG | 152 | 211 | 383 |

| .30-cal. BAR | 92 | 72 | 300 |

| .30-cal. LMG | 179 | 169 | 260 |

| .30-cal. HMG | 16 | 16 | 24 |

| 2.36in. bazooka | 445 | 466 | 567 |

| .50-cal. HMG | 109 | 92 | 165 |

| 60mm mortar | 75 | 75 | 81 |

| 81mm mortar | 36 | 36 | 42 |

| AT gun | 44 | 16 | 50 |

| 75mm howitzer | 36 | 40 | 60 |

| Handcart | 253 | 312 | 185 |

| Motorcycle | 207 | 236 | 260 |

| 1/4-ton jeep | 323 | 345 | 750 |

| 3/4-ton truck | 17 | 24 | 35 |

| 11/2-ton truck | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 21/2-ton truck | 85 | 90 | 237 |

| 1/4-ton trailer | 215 | 290 | 531 |

| 1-ton trailer | 100 | 88 | 226 |

| Liaison aircraft | 8 | 8 | 10 |

As Gen. Maxwell Taylor pointed out after the war, of the 192 days spent in combat by the 101st Airborne Division, only four days were spent as an isolated airborne formation while the remaining 188 days of combat were spent as a conventional ground division as part of a larger Allied formation.

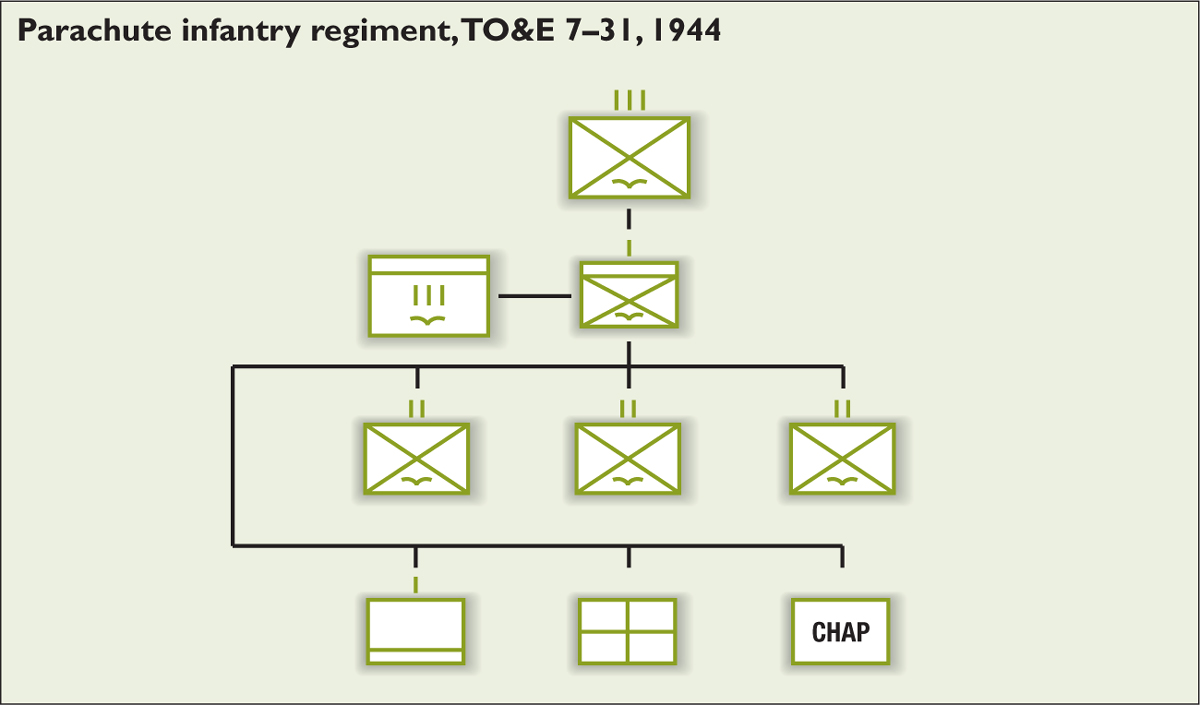

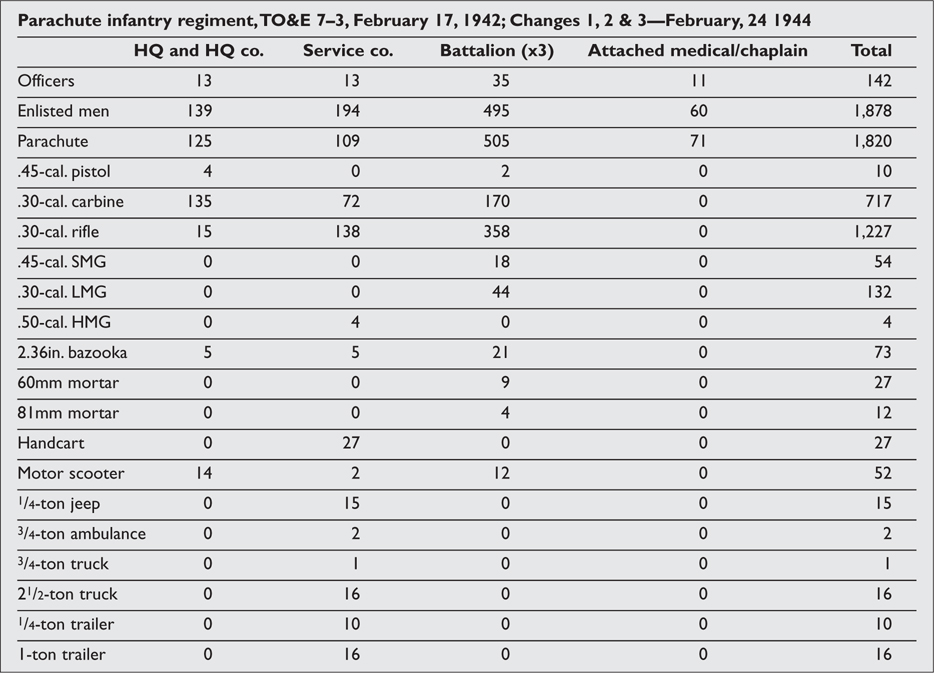

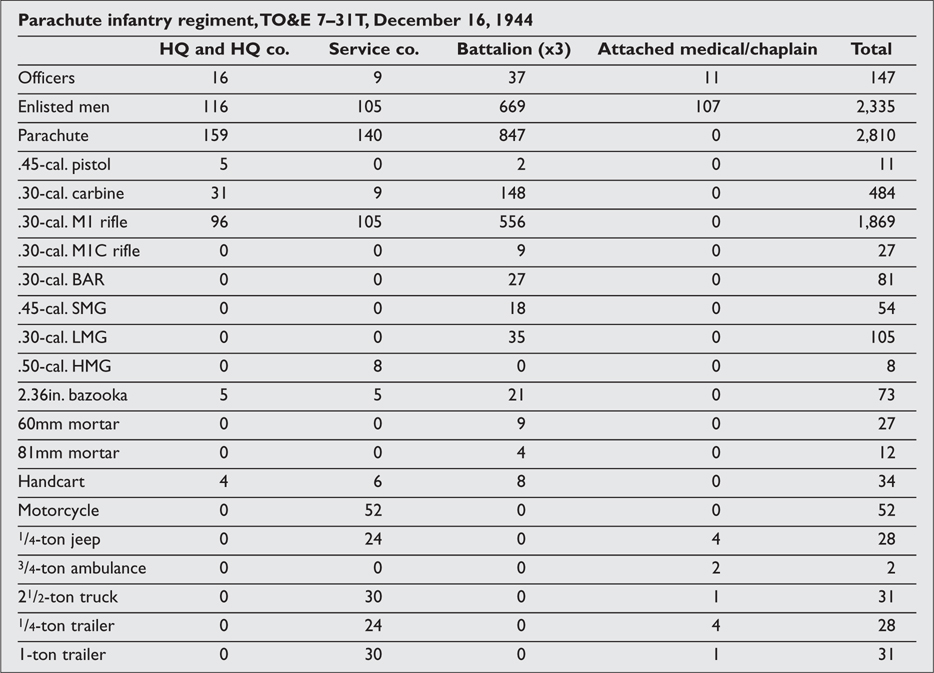

The parachute infantry regiment (PIR) was the oldest of the airborne formations, pre-dating the airborne division. The first table of organization was authorized on February 17, 1942, and underwent three changes prior to D-Day: in July 1942, October 1943 and February 1944. Most of these were fairly modest, for example deleting the M1903 Springfield .30-cal. sniper rifle, and adding the 2.36in. bazooka anti-tank rocket launcher. The first large changes occurred under the December 1944 TO&E, with the PIR receiving additional troops and equipment. The most noticeable change was the increase in strength in the parachute infantry battalions due to the addition of a third rifle squad in each rifle platoon; previously there had only been two. Even after the expansion, this formation was only about two-thirds the size of a conventional infantry regiment. This was in part due to an absence of some of the supporting arms, for example the lack of the cannon company and anti-tank company found in a conventional infantry regiment. In addition, the organizational structure and logistical support was far more austere: 16 versus 34 2½-ton trucks; one versus four 1¾- and 1½-ton trucks; 15 versus 149 jeeps. Furthermore, the discrepancy was even greater when comparing the number of vehicles actually deployed in combat, since, in the case of the parachute regiment, only a portion of the jeeps were delivered if there was enough space in the gliders and no heavier trucks were airlifted.

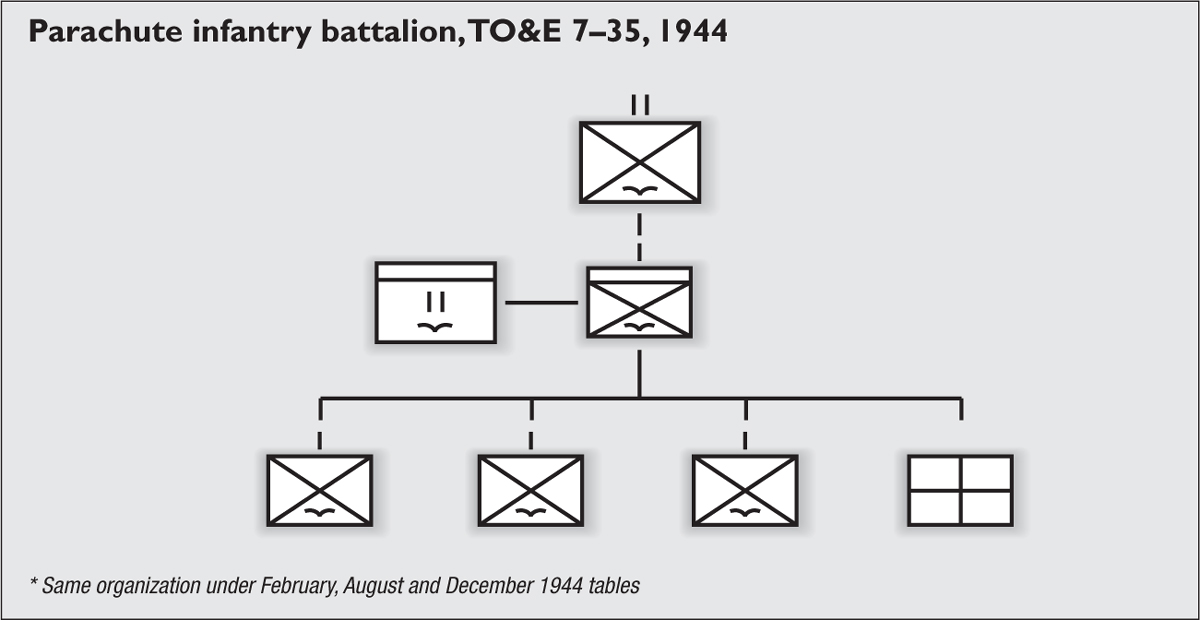

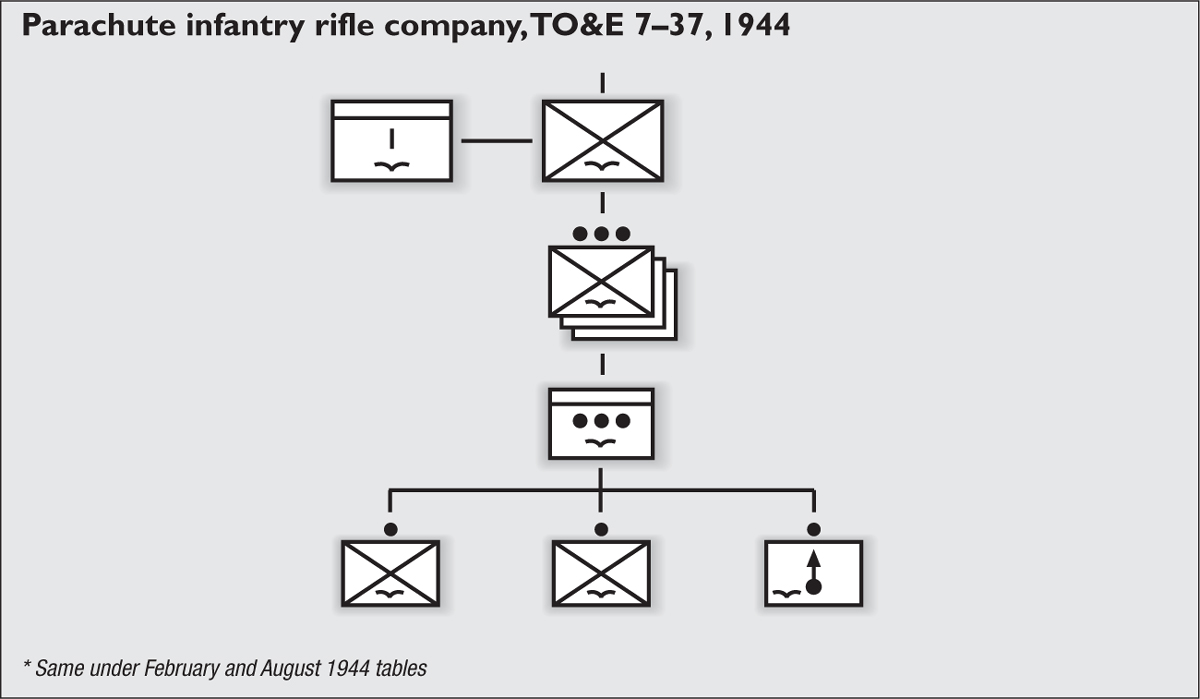

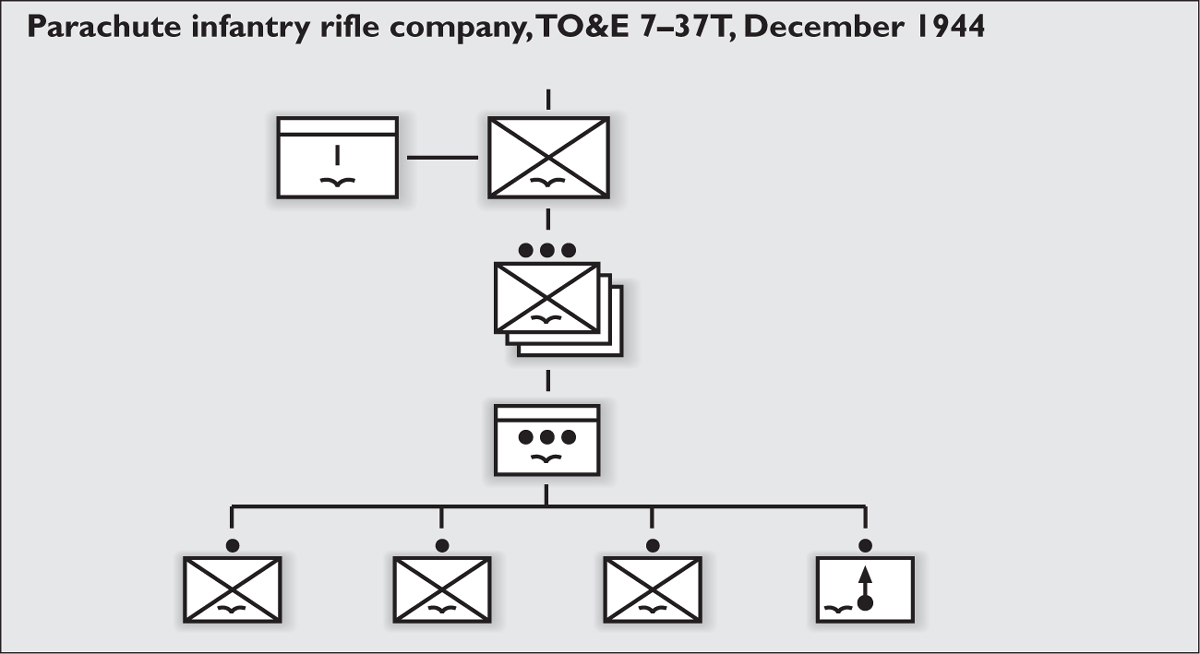

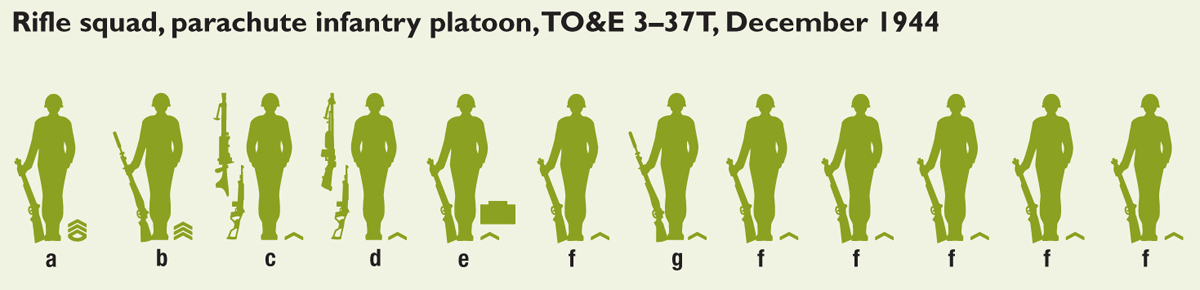

The parachute infantry regiment’s basic tactical unit was the parachute infantry battalion. The structure of the battalion changed little until the December 1944 tentative table, which added an additional rifle squad to each rifle platoon, thereby considerably increasing the overall strength of the battalion. The battalion’s basic tactical unit was the rifle company, which consisted of a company headquarters and three rifle platoons. The rifle platoon organization under the February 1944 table was a platoon HQ, two rifle squads, and a 60mm mortar squad; the December 1944 table added a third rifle squad increasing the platoon strength from 36 to 49. The platoon headquarters was led by a 1st lieutenant, with an assistant 2nd lieutenant added under the December 1944 table. The HQ also included five enlisted men, consisting of the platoon sergeant, a platoon guide sergeant, two messengers and a radioman equipped with an SCR-536 handy-talkie; support weapons included a bazooka and a sniper rifle. The rifle squads consisted of 12 enlisted men led by two sergeants: a squad leader and an assistant squad leader/demolitions specialist. The squad had seven riflemen plus a three-man machine-gun team armed with the .30-cal. Browning light machine gun consisting of a gunner, assistant gunner and ammo bearer with up to two light machine guns. All members of the rifle squad were armed with .30-cal. M1 Garand rifles except for the machine-gun team, who were armed with .30-cal. carbines. The December 1944 table substituted a .30-cal. BAR (Browning automatic rifle) for one of the .30-cal. light machine guns. Although the same size as a regular infantry company’s rifle squad, the parachute rifle squad had more firepower with two .30-cal. machine guns/BARs versus one BAR in the regular squad. The mortar squad included six enlisted men led by a squad sergeant, a mortar gunner, an assistant gunner and three ammo bearers. The mortar squad’s primary weapon was a 60mm M2 mortar and all squad members were armed with a .30-cal. carbine. It should be noted that paratrooper armament was heavier than the tables suggest. Although the tables did not authorize paratroopers to carry additional weapons such as a pistol, in practice many paratroopers obtained pistols almost as a matter of routine. Indeed, the postwar General Board study recommended that a secondary pistol armament become a standard equipment authorization based on the wartime experience.

A paratrooper of the 101st Airborne Division prepares his gear at an airfield in England on the night of June 5, prior to the Operation Neptune jump in Normandy. (NARA)

A stick of paratroopers of the 1/501st PIR wait for the green light inside a C-47 over the Netherlands during Operation Market in September 1944. (NARA)

| Parachute infantry battalion, TO&E 7–35, 1944, February 17, 1942, Changes 1 & 2—February 24, 1944 | ||||

| HQ & HQ co. | Rifle company (x3) | Attached medical | Total | |

| Officers | 11 | 8 | 2 | 37 |

| Enlisted men | 138 | 119 | 17 | 512 |

| Parachute | 124 | 127 | 19 | 524 |

| .45-cal. pistol | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| .30-cal. carbine | 107 | 21 | 0 | 170 |

| .30-cal. rifle | 40 | 106 | 0 | 358 |

| .45-cal. SMG | 0 | 6 | 0 | 18 |

| .30-cal. LMG | 8 | 12 | 0 | 44 |

| 2.36in. bazooka | 9 | 4 | 0 | 21 |

| 60mm mortar | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| 81mm mortar | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Motor scooter | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Parachute infantry battalion, TO&E 7–35T, December 16. 1944 | ||||

| HQ & HQ co. | Rifle company (x3) | Attached medical | Total | |

| Officers | 13 | 8 | 2 | 38 |

| Enlisted men | 165 | 168 | 28 | 697 |

| T-5 parachute | 214 | 211 | 0 | 847 |

| .45-cal. pistol | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| .30-cal. carbine | 52 | 32 | 0 | 148 |

| .30-cal. M1 rifle | 124 | 144 | 0 | 556 |

| .30-cal. M1C rifle | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| .30-cal. BAR | 0 | 9 | 0 | 27 |

| .45-cal. SMG | 0 | 6 | 0 | 18 |

| .30-cal. LMG | 8 | 9 | 0 | 35 |

| 2.36in. bazooka | 9 | 4 | 0 | 21 |

| 60mm mortar | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| 81mm mortar | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Handcart | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

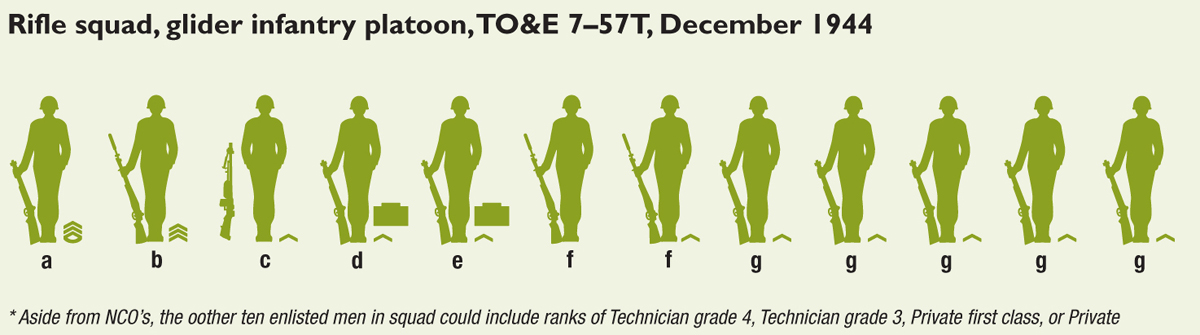

Legend

a Squad Leader

b Assistant Squad Leader (demolitions)

c MG Gunner

d Assistant MG Gunner

e Ammo Bearer

f Rifleman

g Rifleman (grenadier)

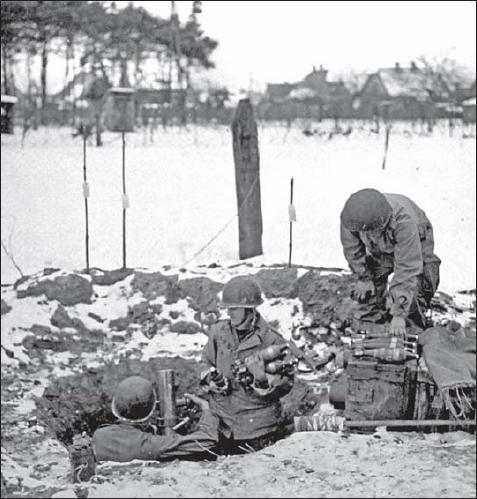

Artillery support in the airborne regiments was weak, so the four 81mm mortars found in each battalion’s headquarters company were especially vital for fire support. This 81mm mortar from the 101st Airborne Division is seen in action on January 31, 1945, towards the end of the Ardennes campaign. (NARA)

Legend

a Squad Leader

b Assistant Squad Leader

c Auto Rifleman

d Assistant Auto Rifleman

e Ammo Bearer

f Rifleman (grenadier)

g Rifleman

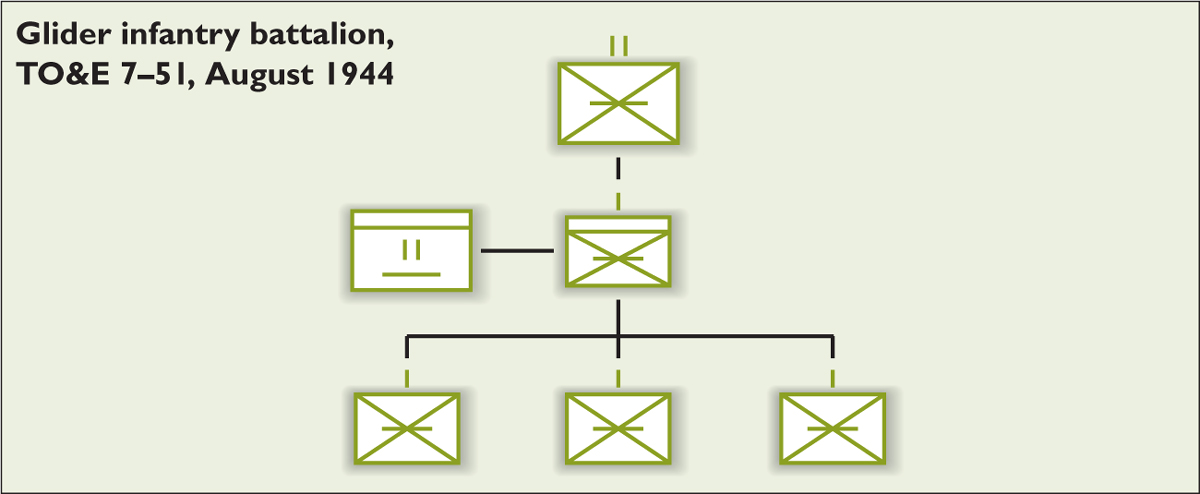

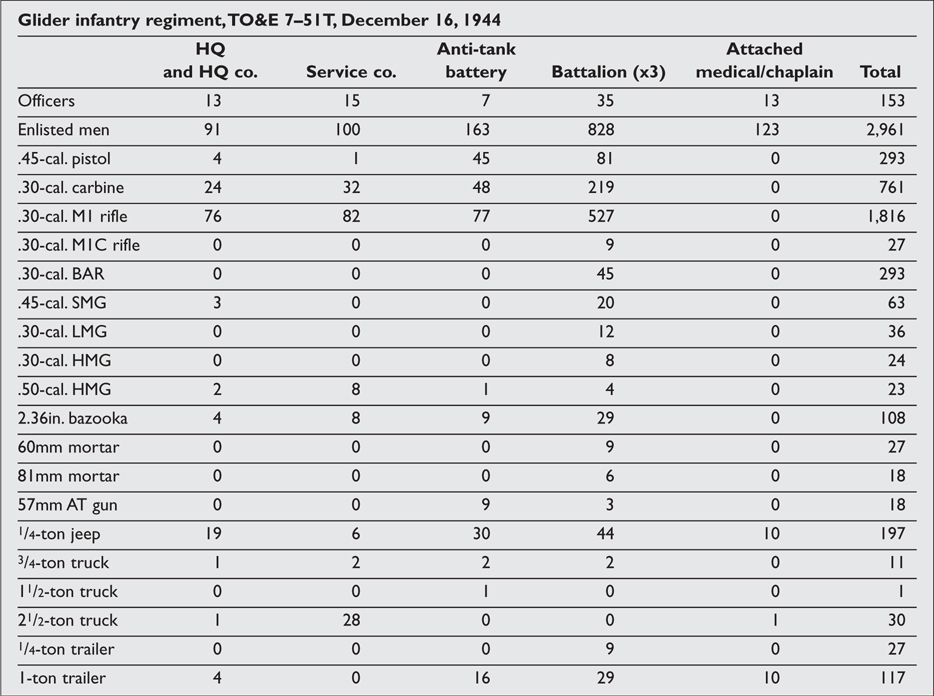

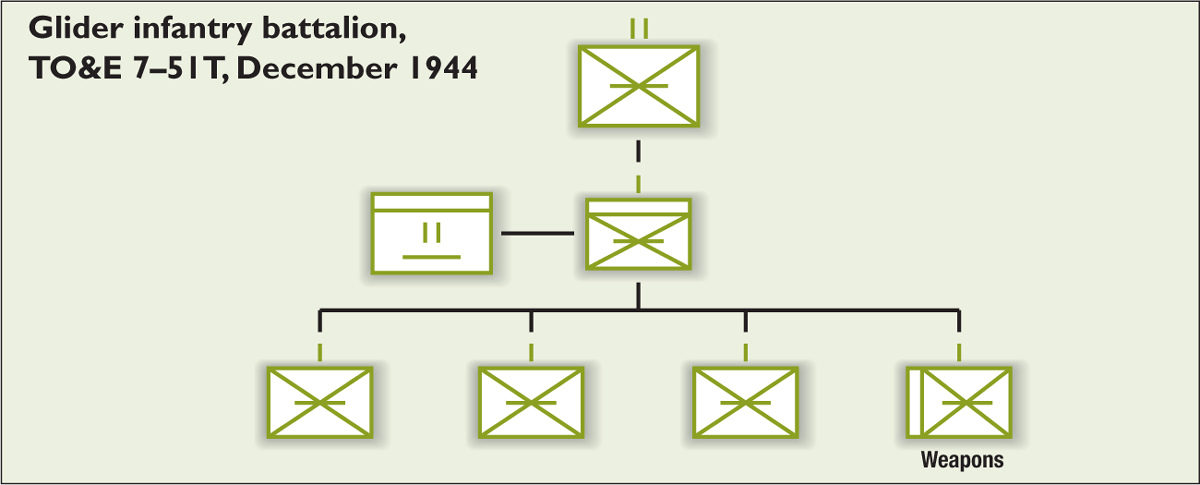

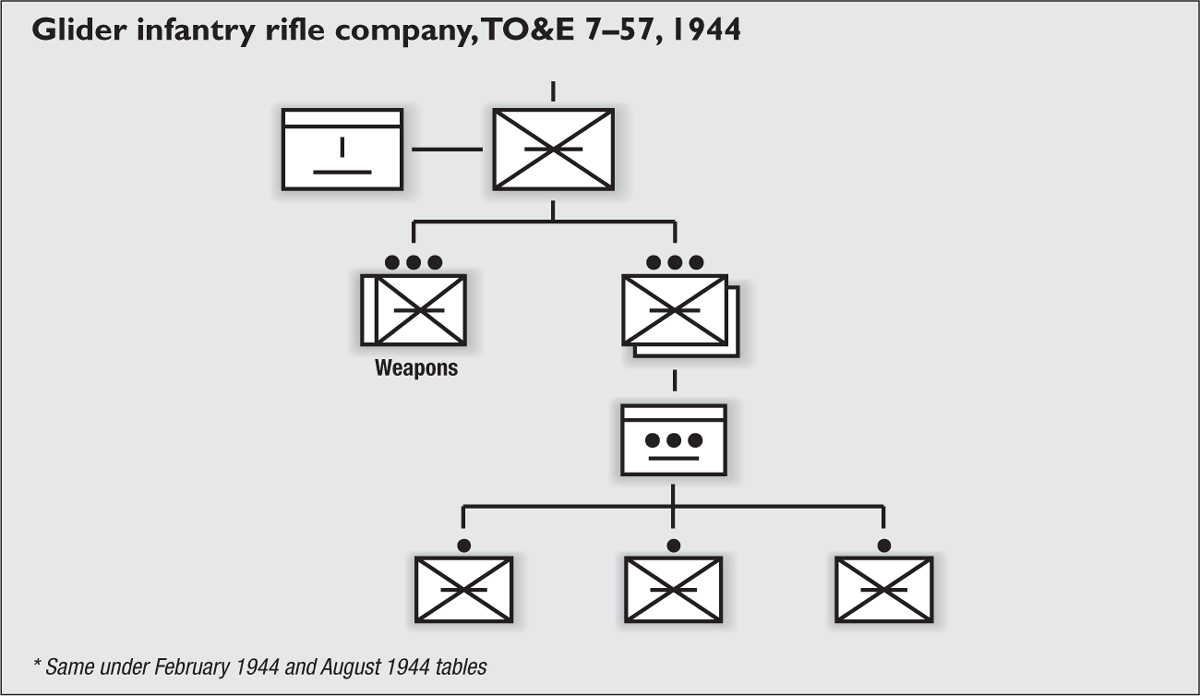

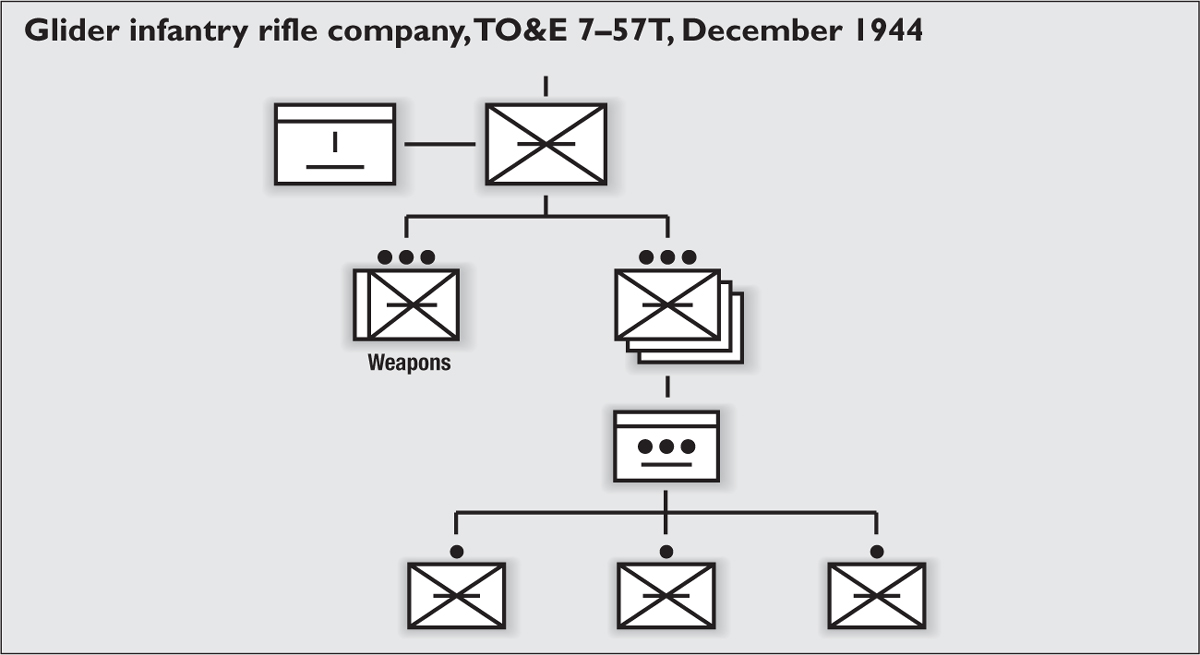

The glider infantry regiment’s basic tactical unit was the glider infantry battalion. As in the case of other airborne units, the regiment expanded under the December 1944 TO&E, primarily due to the addition of a third glider infantry battalion and the addition of a third rifle platoon in each company, bringing it more in line with parachute infantry and conventional infantry organization. The glider infantry battalion was organized somewhat differently from the parachute infantry battalion since the added airlift capability permitted the unit to bring in heavier weapons than was the case with the parachute battalion. So besides the three rifle companies, each battalion also deployed a jeep-borne heavy weapons company, which included eight .30-cal heavy machine guns and six 81mm mortars; the HQ company had an anti-tank platoon with three towed 57mm anti-tank guns. The use of gliders also permitted the battalion to bring in more vehicles, totaling 44 jeeps.

Anti-tank weapons were limited in the airborne division and the 2.36in. bazooka was the backbone of anti-tank defense. This team from the 325th GIR, 82nd Airborne Division, is seen covering a road in Belgium on December 20, 1944, during the division’s efforts to halt the advance of the 1st SS-Panzer Division. (NARA)

The glider infantry company also had a different organization from its parachute counterpart, having a weapons platoon and two rifle platoons versus three parachute rifle platoons under the February 1944 tables. The weapons platoon had two .30-cal. heavy machine guns and two 60mm mortars. The glider company increased under the December 1944 tables when a third rifle platoon was added, making them larger than the parachute infantry companies. This organizational difference also affected the glider platoons and squads since the heavy weapons were concentrated in the glider company’s weapons platoons instead of being spread out as in the parachute platoons. So the glider platoons initially consisted of three rifle squads, with 12 riflemen per squad all equipped with .30-cal. rifles. The December 1944 reorganization changed this, adding a BAR to the rifle squads and thereby bringing them closer to regular infantry squad organization.

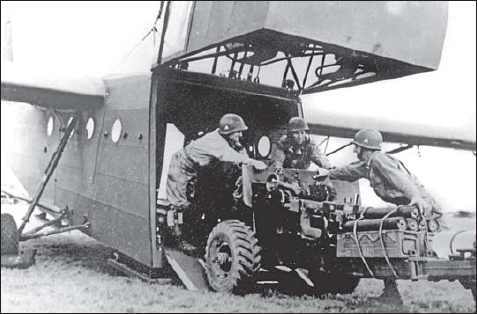

Gliders were the only method of delivering heavier equipment such as jeeps. This is a medical jeep of the 327th GIR being loaded aboard of CG-4A of the 434th Troop Carrier Group on September 17, 1944, part of the two glider serials conducted on the first day of Operation Market from Aldermaston. The prong fitted on the glider nose is a Griswold reinforcement added to the nose of CG-4A gliders to give the crew added protection. (NARA)

The water-cooled M1917A1 .30-cal. heavy machine gun was not commonly found in the airborne division, but was used by the machine-gun platoon of the headquarters company in each glider infantry battalion. This example is in use by a team from the 82nd Airborne Division in Normandy after D-Day. (MHI)

This CG-4A from Serial A-47 of the 434th Troop Carrier Group has lost much of the fabric from its nose after having landed at Landing Zone W during Operation Market.The CG-4A had a special mechanism for quickly opening the nose to disembark its jeep cargo. (NARA)

The Horsa glider was not as popular in US glider units as the smaller CG-4A due to its higher maintenance demands and the vulnerability of its plywood construction to break-up on landing. Here, some glider infantry of the 82nd Airborne Division look over a Horsa that landed on D-Day. (NARA)

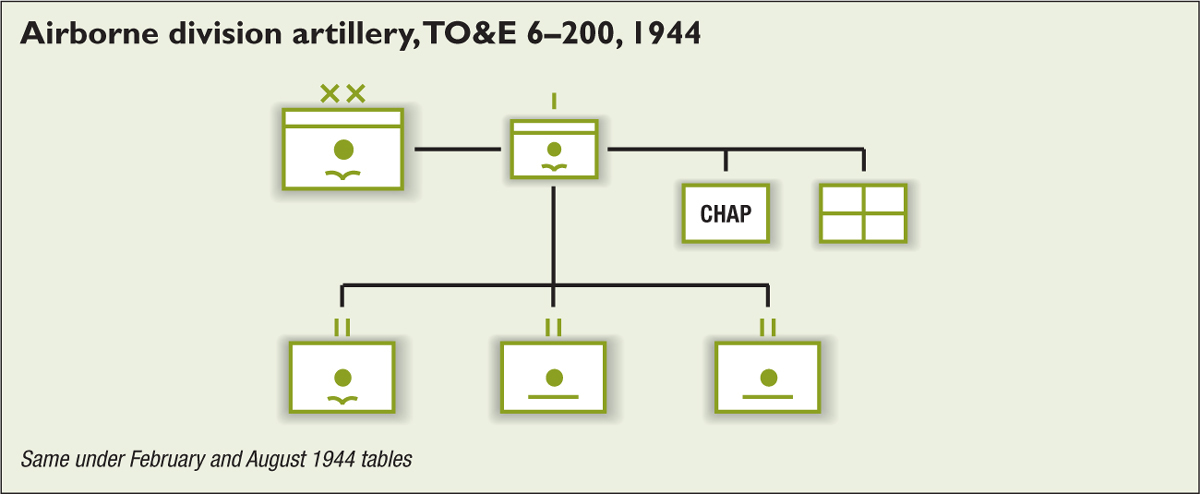

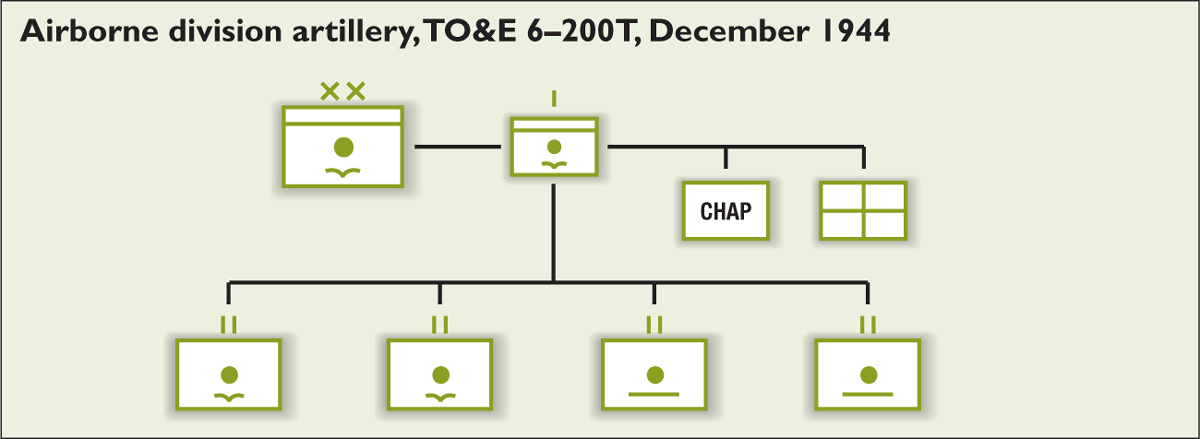

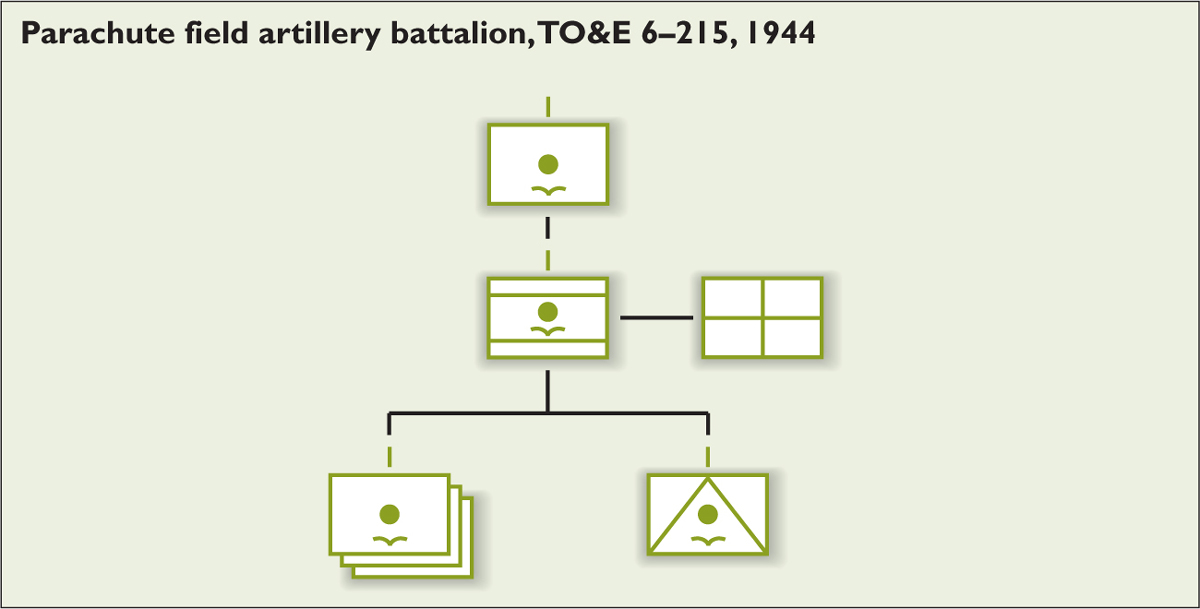

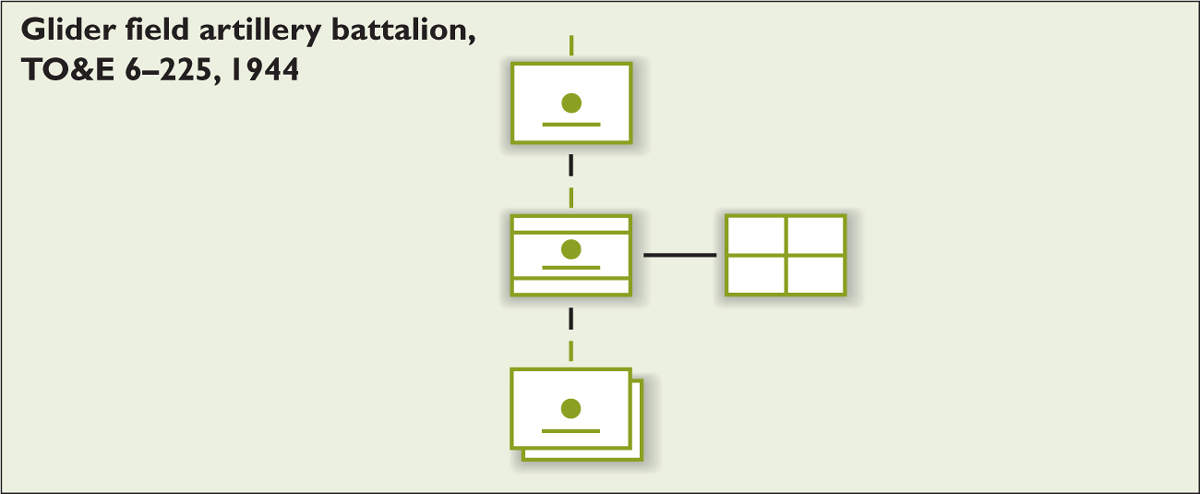

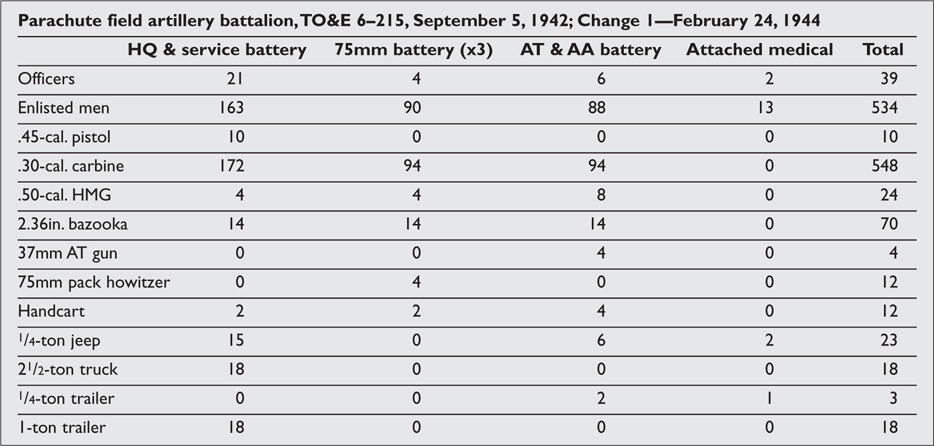

Divisional artillery in an airborne division was significantly lighter than in infantry divisions due to the limitations of airlift. The February 1944 tables allotted three 75mm pack howitzer battalions, one parachute and two glider, compared to four battalions in an infantry division, three 105mm and one 155mm howitzer. The standard weapon in the airborne divisions was the 75mm pack howitzer, which was broken down into several loads for parachute delivery or which could be carried inside the CG-4A glider. It took nine paracrate loads to deliver a single pack howitzer by parachute: 1) rear trails; 2) rear trails; 3) gun sleigh; 4) gun cradle; 5) gun tube; 6) gun breech; 7) wheels; 8) ten rounds of ammunition; 9) para-caisson and six rounds of ammo. The parachute-dropped pack howitzer proved to be a liability in combat as, if there was any dispersion during the drop, the missing parts prevented the weapon from being assembled. The British attempted to circumvent this problem by developing a parachute pallet large enough for the pack howitzer to be dropped from a heavy bomber and these were used on D-Day in Normandy. However, the bomb bays on US bombers were not as well suited to this configuration as those on the British bombers, so US divisions in World War II did not use this method of delivery.

The M3 105mm howitzer had been designed specifically for airborne use but it was not authorized under the wartime tables until December 1944 and even then as an option. However, in practice the divisions began receiving an additional battalion equipped with this weapon in time for D-Day and, by 1945, the weapon was in service in all the airborne divisions in the ETO, using glider delivery.

There was some hope that the new recoilless rifles being developed in 1944 could solve the problems of airborne artillery. Fifty M18 57mm recoilless rifles were shipped to the ETO in March 1945 and could be air dropped using the M10 paracrate, which included the weapon and 14 rounds of ammunition. Some of these were delivered to the 17th Airborne Division and used in Operation Varsity. The 57mm recoilless rifle was not powerful enough to substitute for the 75mm pack howitzer, and instead was used as an infantry heavy weapon for direct support, bridging the gap between the 2.36in. bazooka and the pack howitzer. A more effective artillery weapon was the M20 75mm recoilless rifle, which was also shipped to the ETO in small numbers shortly before Operation Varsity. This was a crew-served weapon mounted on a tripod. The 75mm recoilless rifle proved well suited as dual-role weapon suitable for either anti-tank or direct-fire missions. During the Operation Varsity air-landings, 75mm recoilless rifles with the 507th PIR accounted for at least three German armored vehicles. Larger recoilless rifles were also under development but were not fielded prior to the end of the war.

A major problem facing the parachute field artillery was the need to break the 75mm M1A1 pack howitzer into several loads for parachute delivery. This created the risk that key elements would be lost during the airdrop. Here, gunners from the 101st Airborne Division re-assemble a 75mm pack howitzer following a practice jump near Newbury in England on November 23, 1943. (MHI)

There was some hope that innovations in artillery could help improve the airborne division’s firepower. Recoilless rifles entered production too late to have a major effect, but a modest number of 57mm recoilless rifles were deployed with the 17th Airborne Division for Operation Varsity in March 1945 as seen here. (NARA)

| Glider field artillery battalion, TO&E 6–225, September 5, 1942; Change 1—February 24, 1944 | ||||

| HQ & service battery | 75mm battery (x2) | Attached medical | Total | |

| Officers | 15 | 4 | 2 | 25 |

| Enlisted men | 94 | 133 | 11 | 371 |

| .45-cal. pistol | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| .30-cal. carbine | 97 | 137 | 0 | 371 |

| .50-cal. HMG | 3 | 6 | 0 | 15 |

| 2.36in. bazooka | 14 | 18 | 0 | 50 |

| 37mm AT gun | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75mm pack howitzer | 0 | 6 | 0 | 12 |

| Handcart | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Motor scooter | 9 | 4 | 0 | 17 |

| 1/4-ton jeep | 5 | 16 | 2 | 39 |

| 3/4-ton truck | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 21/2-ton truck | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 1/4-ton trailer | 5 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| 1-ton trailer | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Liaison aircraft | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

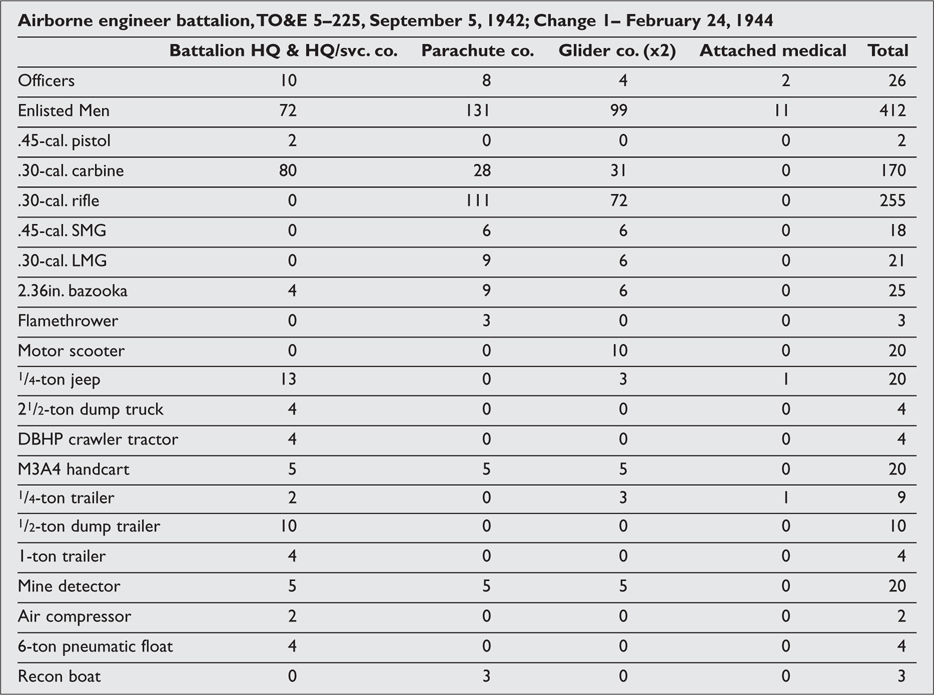

The airborne engineer battalion was unusual in that it was a mixed parachute/glider formation with two of its companies configured for glider delivery and one for parachute delivery, reflecting its usual deployment on the basis of one company per parachute/glider infantry regiment. The battalion was the usual “jack-of-all-trades,” typical of engineer formations, but with a stronger emphasis on demolition work due to the nature of airborne missions. The engineer battalion was also responsible for some limited construction tasks, and was authorized a special lightweight dozer and grader that could be delivered by glider. There had been some consideration to developing a divisional capability for creating improvised runway improvement/construction to assist in follow-on air-landing missions, but this mission was usually pushed off on the AAF engineers who already specialized in these tasks.

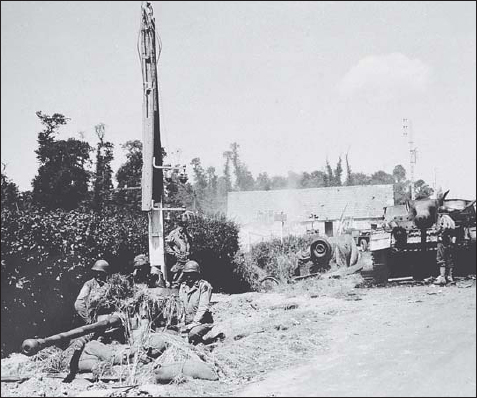

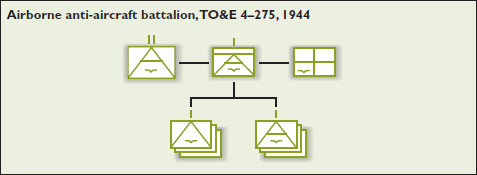

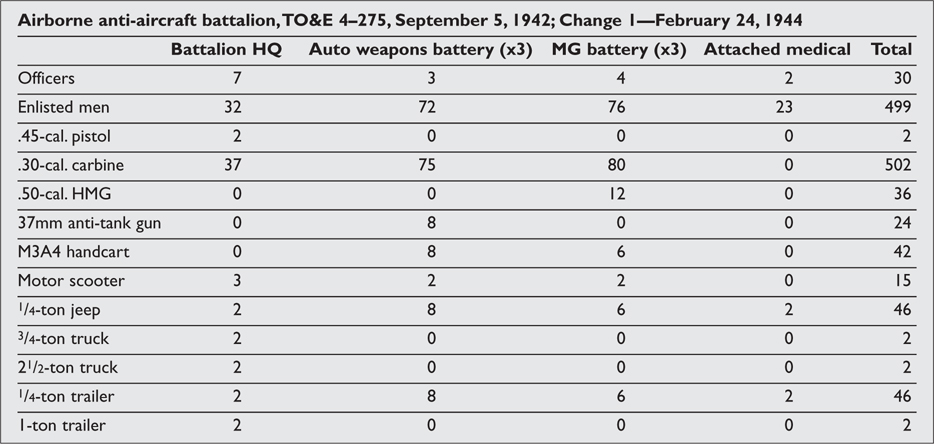

Although called an anti-aircraft battalion, this unit was in fact a heavy weapons unit with three batteries of air-defense machine guns and three batteries of anti-tank guns. The air defense capability was generally not a high priority due to Allied air superiority, though the .50-cal. heavy machine guns could be used for general support. In the event of limitations on airlift, preference went to the battalion’s anti-tank weapons and these battalions were seldom deployed in full strength. The battalion’s anti-aircraft weapons were primarily the .50-cal. heavy machine gun, though under the August 1944 table the battalion was allotted the larger 37mm automatic cannon. However, this was removed under the final December 1944 table as the weapon was heavy, difficult to deliver and largely unnecessary. As mentioned earlier, the 1944 tables authorized the 37mm anti-tank gun, but the British 6-pdr was substituted in the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions prior to the Normandy landings. These weapons proved very useful in stemming several German armored attacks in Normandy so, by the time of the December 1944 tables, the 57mm gun had become officially accepted in spite of the need for glider delivery. The postwar General Board study concluded that this unit was unnecessary and its tasks better handled by artillery units since the new recoilless rifles were suitable for the anti-tank role.

The standard anti-aircraft weapon in the airborne divisions was the pedestal-mounted .50-cal. heavy machine gun, and an example is seen here near Wesel in March 1945 being used for perimeter security due to the lack of a significant air threat. (MHI)

The airborne division had relatively weak anti-tank capabilities, relying on bazookas and small numbers of 6-pdr (57mm) anti-tank guns. Nevertheless, these proved adequate to beat off an armored attack by the 17th SS-Panzergrenadier Division near Carentan as seen here with a knocked-out StuG IV assault gun behind a 6-pdr of the 82nd Airborne Division on June 13, 1944. (NARA)

Although the British experimented with parachute dropping the airborne 6-pdr from bombers, the US relied solely on gliders for delivery. This 6-pdr (57mm) anti-tank gun is being loaded along with its ammunition by the 81st Airborne Anti-aircraft Battalion, 101st Airborne Division, prior to Operation Market in September 1944. (MHI)

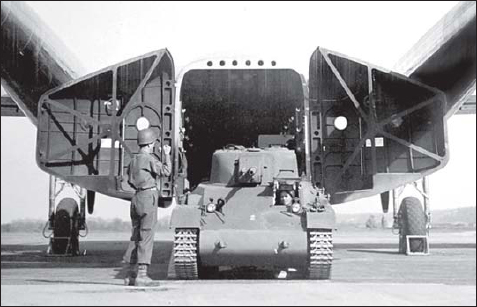

The US Army considered forming special airborne tank units after the successful use of German paratroops at Eben Emael in 1940 and Crete in 1941, but lacked a suitable ultra-light tank. With the decision to proceed with the T9 airborne tank, in February 1943 the AGF ordered the Armored Force to organize an airborne tank battalion and develop suitable training and doctrine in cooperation with the Airborne Command. However, the Airborne Command was skeptical about the need for a battalion-sized formation due to the airlift problem, so the first unit was trimmed down to a company. The plan was to carry the tank under a C-54 transport, which would require air-landing since no large glider was available. The 151st Airborne Tank Company was activated at Ft. Knox on August 15, 1943, followed by the 28th Airborne Tank Battalion on December 6, 1943.

In spite of considerable enthusiasm within the army for the airborne tank concept, the Marmon Herrington T9E1 airborne tank proved to be so disappointing from a technical standpoint that enthusiasm soon waned. The 151st Airborne Tank Company was not available in time for deployment with airborne units on D-Day, and in July 1944 was transferred from Ft. Knox to Camp Mackall, North Carolina, where it was quickly forgotten. The 28th Airborne Tank Battalion was reorganized as a conventional tank battalion in October 1944. The T9E1 airborne tank was finally accepted for service as the M22 airborne tank, and apparently a small number were sent to the 6th Army Group in 1944 in Alsace for potential use by the 1st Airborne Task Force. However, no airborne tank unit was deployed into combat during the war, in part due to a lack of a means to deliver them.

Although some 830 M22 light airborne tanks were manufactured and airborne tank units formed, the lack of suitable airlift prevented their use by the US airborne divisions in World War II. The Fairchild C-82 Packet transport was under development when the war in Europe ended, and here one is seen loading an M22 light airborne tank. (NARA)

The lack of an airborne tank battalion led the 82nd Airborne Division to develop their own lightly armored version of the jeep for conducting reconnaissance and this patrol is seen in the Ardennes in December 1944. (NARA)

The British used airborne tanks on D-Day and again during Operation Varsity in 1945, delivering them with the enormous Hamilcar glider. However, the US Airborne Command never saw enough need for light tanks, so no Hamilcar gliders were requested from Britain. Curiously enough, the 17th Airborne Division did receive some support from M22 airborne tanks during Operation Varsity, but in British service with the 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment.