In general, the weapons used by the airborne divisions were the same as those in other US Army divisions, though a few weapons were developed specifically for the airborne. The standard M1 .30-cal. carbine was modified with a folding stock for airborne use to make it more compact. This became the standard sidearm in the airborne divisions, though it was unpopular in combat units due to its reliance on .30-cal. pistol ammunition, which was deemed to have insufficient range and stopping power. The other infantry weapons used by the airborne were the same as those issued to other infantry units though, as mentioned below, the tables of equipment differed. The paratroops did have some accessories for their small arms used when parachuting. The Griswold bag was designed to carry an M1 .30-cal. rifle disassembled into two parts during the jump, but some paratroopers preferred to jump with the rifle assembled and ready for use in spite of the potential landing hazard. A number of other weapons bags were developed for the jump, some of which were attached by a cord and lowered prior to landing to reduce the probability of injury. The one weapon found more commonly in paratrooper units than in other infantry formations was some form of knife, typically an M3 fighting knife or M2 switchblade. This was necessary to cut parachute lines in the event that the paratrooper landed in a tree, but paratroopers were also trained to use the knife as a weapon, especially for silent night attacks.

There was a significant concern about the threat posed by armored vehicles to the lightly armed airborne formations. Aside from the bazooka, a number of other weapons were issued to airborne troops to deal with this threat. The British No. 82 Gammon grenade was a small cloth bag filled with a 1kg charge of plastic explosive with an attached safeing and arming device. It was designed to be thrown against enemy armored vehicles, with the charge causing spall on the inside face of the Panzer’s armor plate to injure the crew. It was difficult and dangerous to use effectively, but there are recorded cases of paratroopers knocking out German armored vehicles with them. Another last-ditch anti-tank weapon was the British Hawkins ATK 75 Mk. III anti-tank mine, which was a small rectangular mine powerful enough to blow off a tank track.

Besides the individual weapons, paratroopers had several specialized items of battledress and personal equipment. The paratrooper’s M2 helmet was essentially similar to the standard infantry M1 helmet but, instead of the usual helmet strap, it had a more elaborate inverse A strap culminating in a leather chin strap. An improved paratrooper helmet, the M1C, entered development in October 1943 with a modified chin-strap suspension, but didn’t become available until after the Normandy drops. Glider infantry wore the standard infantry helmet. Paratroopers were also issued brown-leather high-lace “jump” boots instead of the standard infantry boots; glider infantry received standard infantry boots. The paratroopers’ M1942 battledress was distinct from that of the regular infantry due to a larger number of pockets, resulting in their legendary nickname “the devils in the baggy pants.” When the new green M1943 battledress was issued after Normandy, there was no distinct paratrooper version though some units did modify their clothing with additional pockets.

The standard parachute used in 1944 was the T-5, which consisted of a main pack worn on the back with an associated harness. They were delivered either with a camouflaged or white canopy. Although there were efforts made to use only the camouflaged canopy during the Normandy night drop, in fact white canopies were also used. Unlike German and British paratroopers, US paratroopers also were issued an associated reserve AN 6513-1A chest pack, though it was of dubious utility in view of the low altitude at which most combat jumps were conducted. The T-5’s most serious shortcoming was the lack of a quick-release on the harness, which was very dangerous if the paratrooper had the misfortune of landing in water as it was difficult and time-consuming to escape the harness. Due to the number of paratroopers drowned after landing in flooded areas in Normandy, divisional riggers modified the T-5’s harnesses to incorporate a quick-release mechanism derived from the British design. The improved T-7 parachute with a quick-release mechanism was introduced before the end of the war. Besides the individual parachutes, heavier equipment was air dropped using the A-5 parapack container. This was a padded canvas bag with a parachute attached at one end. The parachute was color coded depending on the contents: blue for food rations, green for fuel, red or yellow for ammunition and explosives, and white for medical or signals equipment. For night drops, a small battery-powered lamp was attached which was color coded by attaching clear plastic covers over the bulbs on either end. The parapack was delivered either by pushing it out of the door of the transport aircraft, or suspended under the belly of the C-47 using a “para-rack,” which shielded the container from the airstream and contained the necessary release clips.

At the time of the D-Day landings, the AAF element of the airborne force was IX Troop Carrier Command, part of the Ninth Air Force, under the command of Brig. Gen. Paul Williams. This command consisted of three troop carrier wings with 14 troop carrier groups, and five groups per wing; the 50th TCW, which was the last to arrive, only had four groups. In addition, there was the Provisional Pathfinder Group, directly under IX TCC headquarters, which would be responsible for delivering the airborne pathfinder teams in advance of the main airdrop. Each group typically was allotted four squadrons with a nominal strength of 64 operational aircraft and 16 in reserve. Each squadron had a nominal strength of 12 aircraft plus one as an attrition spare. In total, IX TCC deployed 56 squadrons of C-47 and C-53 transport aircraft totaling some 1,022 aircraft and crew in June 1944. To foster better joint training, the troop carrier groups were paired with the divisions they would be lifting. So the 52nd Wing was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division and the 53rd to the 101st Airborne.

The workhorse of the troop carrier units was the Douglas C-47 Skytrain. The antenna below the cockpit window is for the Rebecca homing system used for navigation to the drop zone. “Empress Mary Ellen” served with the 304th Troop Carrier Squadron, 442nd TCG, 50th TCW, and is seen here at Vertus, France, on February 26, 1945, with an ample array of paratroop, glider and supply missions marked on the side of the fuselage. (MHI)

There were continual debates between the First Allied Airborne Army and ground commanders like Bradley over the diversion of troop carrier units to supply missions. Flown by the 439th Troop Carrier Group on February 13–14, Operation Red Ball was an unusual fuel-supply mission in that the supplies were landed from the air near Bleialf on the Belgian–German border to support the river-crossing operations along the Saeur River. (MHI)

The principal transport aircraft of the troop carrier squadrons was the Douglas C-47 Skytrain, a military derivative of the famous DC-3 airliner. The C-47 differed from its civilian counterpart in numerous details, but most noticeably in the spartan interior configuration and the provision of a large access door on the left rear fuselage, which could be employed for cargo handling as well as paratroop jumps. A portion of the force was equipped with the C-53, which was another militarized version of the DC-3 but without the enlarged cargo door. The other major cargo aircraft of the period, the C-46 Commando, was larger and faster than the C-47 but did not enter production in substantial numbers until 1943. It was not favored for the airborne delivery role due to its performance problems at the slow airdrop speeds. As a result, the C-47 was the principal airlift aircraft for US airborne operations in World War II. In 1945, the attitude towards the C-46 shifted due to the desire to be able to drop paratroopers more quickly than was possible from the C-47. The C-46 carried more paratroopers than the C-47 and had doors on either side for faster exit. As a result, a small number of C-46s were used on the final airborne mission of the war in the ETO, Operation Varsity in March 1945. However, they were found to be more vulnerable to ground fire than the C-47, a flaw attributed to a hydraulic system that tended to leak inflammable fluid.

The C-47 could be adapted to deliver para-packs using a special belly-mounted frame with fairings to protect the packs during flight. These troop carrier crews are seen installing this system on a C-47 at the airbase in Orléans, France, in March 1945 in preparation for Operation Varsity. (NARA)

More than 160 CG-4A assault gliders of the 434th Troop Carrier Group cover the field at Aldermaston on September 18, 1944, prior to the second day’s glider missions to Landing Zone W in the Netherlands. (MHI)

The principal assault glider in the troop carrier squadrons was the CG-4A, designed by Waco in 1942 to carry 15 fully armed infantrymen. Although the AAF also procured the smaller eight-to-nine seat CG-3A assault glider, it was later deemed too small for combat operations. Production of the CG-4A was authorized in August 1942 before development was complete due to the urgency of the requirement. However, the program was beset by production problems as the AAF limited the production contracts to companies not already heavily involved in aircraft production to avoid distracting the major aircraft manufacturers. As a result, production was scattered between 16 firms, mainly small aircraft firms, which had a great deal of trouble manufacturing these large gliders on schedule. Although intended as an inexpensive aircraft, the inexperience of many of the small firms led to serious cost escalation and the program was plagued as well by manufacturing problems leading to a string of accidents during flights in 1943. Although developed by Waco, the Ford Motor Company was the largest single CG-4A manufacturer and completed 2,418 of the 10,574 built through October 1944. Training flights with the CG-4A revealed that the nose section was very prone to damage. A number of solutions were proposed, and prior to Normandy, 288 CG-4A gliders were modified by installing Griswold reinforcements on the nose, which were a type of spider-shaped reinforcement designed to protect the crew during a hard landing. Other solutions to the problem included installing plywood reinforcing skids under the nose such as the single Parker skid or the triple Corey skid. Some gliders were also fitted with a rear-mounted drogue parachute deployed on landing to slow the glider and reduce the landing distance.

| US troop transport and combat glider production in 1941–45 | ||||||

| 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | Total | |

| C-46 | 1 | 46 | 353 | 1,321 | 1,459 | 3,180 |

| C-47 | 165 | 1,057 | 2,595 | 4,900 | 1,536 | 10,253 |

| CG-4A | 0 | 804 | 5,833 | 4,280 | 2,988 | 13,905 |

| Other gliders | 0 | 3 | 105 | 130 | 440 | 678 |

The CG-4A assault glider was constructed of tubular steel frames with a canvas covering as is evident from this interior view of the cockpit area of one of the few surviving examples, preserved at the airborne museum at Ft. Benning, Georgia. (Author’s collection)

The delays in the manufacture of the CG-4A was one of the reasons that the US airborne divisions had a mix of two parachute and one glider regiments in 1943–44 in spite of the intended mix of two glider and one parachute regiments. Due to the production difficulties with the CG-4A in early 1943, the AAF approached Britain to see if there was any excess capacity in the manufacture of the larger Horsa assault glider. The Horsa was significantly larger than the CG-4A with seating for 28, but tests in 1943 concluded that it could be towed by the C-47. Prior to D-Day, IX TCC had received 360 Horsa gliders of which 301 were still operational. US acquisition of the Horsa was curtailed after the Normandy landing, as the air force complained that it demanded far too much maintenance compared to the CG-4A. The Horsa glider was thoroughly disliked by American glider pilots who felt that its plywood construction made it far more brittle than the CG-4A during landing, causing more wrecks and injuries. Although IX Troop Carrier Group still had 104 Horsa on hand in September 1944 at the time of Operation Market, the strong dislike of this type led to it being sidelined in favor of the exclusive use of the CG-4A.

A larger 30-seat glider, the CG-13A, was also developed of which 81 were shipped to the ETO by the end of the war. However, none were used during Operation Varsity due to the added complexity its introduction would have entailed. An improved 15-seat glider was also developed to replace the CG-4A, and 87 CG-15A were shipped to the ETO, but too late to see use.

Although the Army Air Force had planned to recover and re-use gliders after operations, in the event this proved to be wishful thinking. A majority of the force was invariably damaged beyond repair after smashing into trees, walls and other obstructions, and even those landing in flat fields frequently suffered extensive damage. None of the 222 Horsa gliders used on D-Day were recovered, and only 15 of the 295 CG-4A gliders, a paltry 5 percent. After Operation Market, only 281 gliders were recovered of the 1,409 employed (14 percent) and the results were only slightly better after Operation Varsity with 148 of 908 CG-4A gliders recovered (16 percent). Furthermore, pilots were distrustful of the safety of these battered gliders and in reality none were ever re-used in combat.

The troop carrier groups had a nominal table of 104 glider pilots and prior to D-Day, IX Troop Carrier Command had 1,352 glider pilots and 445 glider co-pilots. After receiving some reinforcements, there were enough glider crews for 951 gliders on the eve of D-Day. A total of 2,100 CG-4A gliders were shipped to Britain by the time of D-Day. There had been some significant attrition due to training, mainly involving landing damage rather than total write-offs, so at the end of May 1944, there were 1,118 CG-4A gliders available.

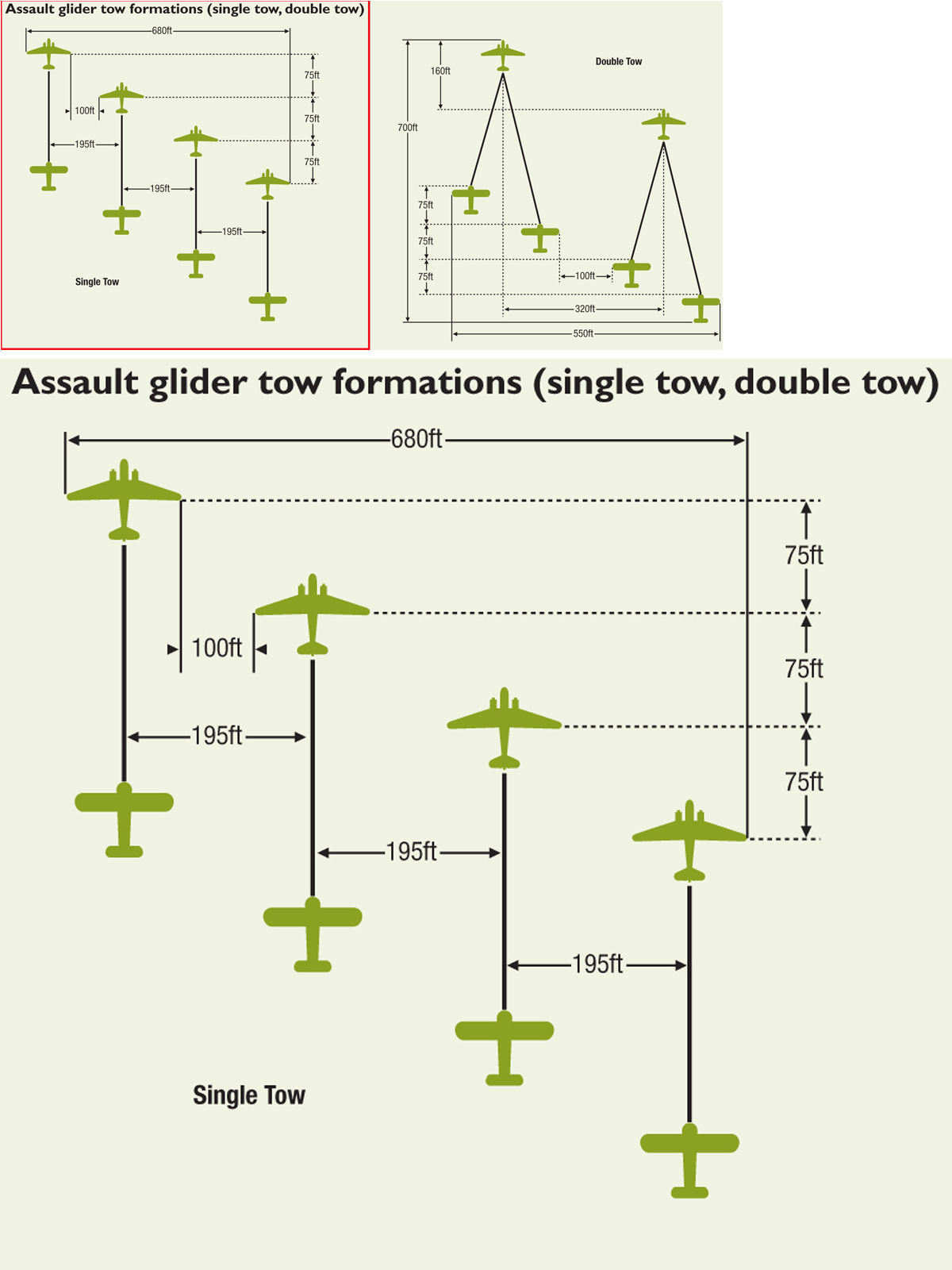

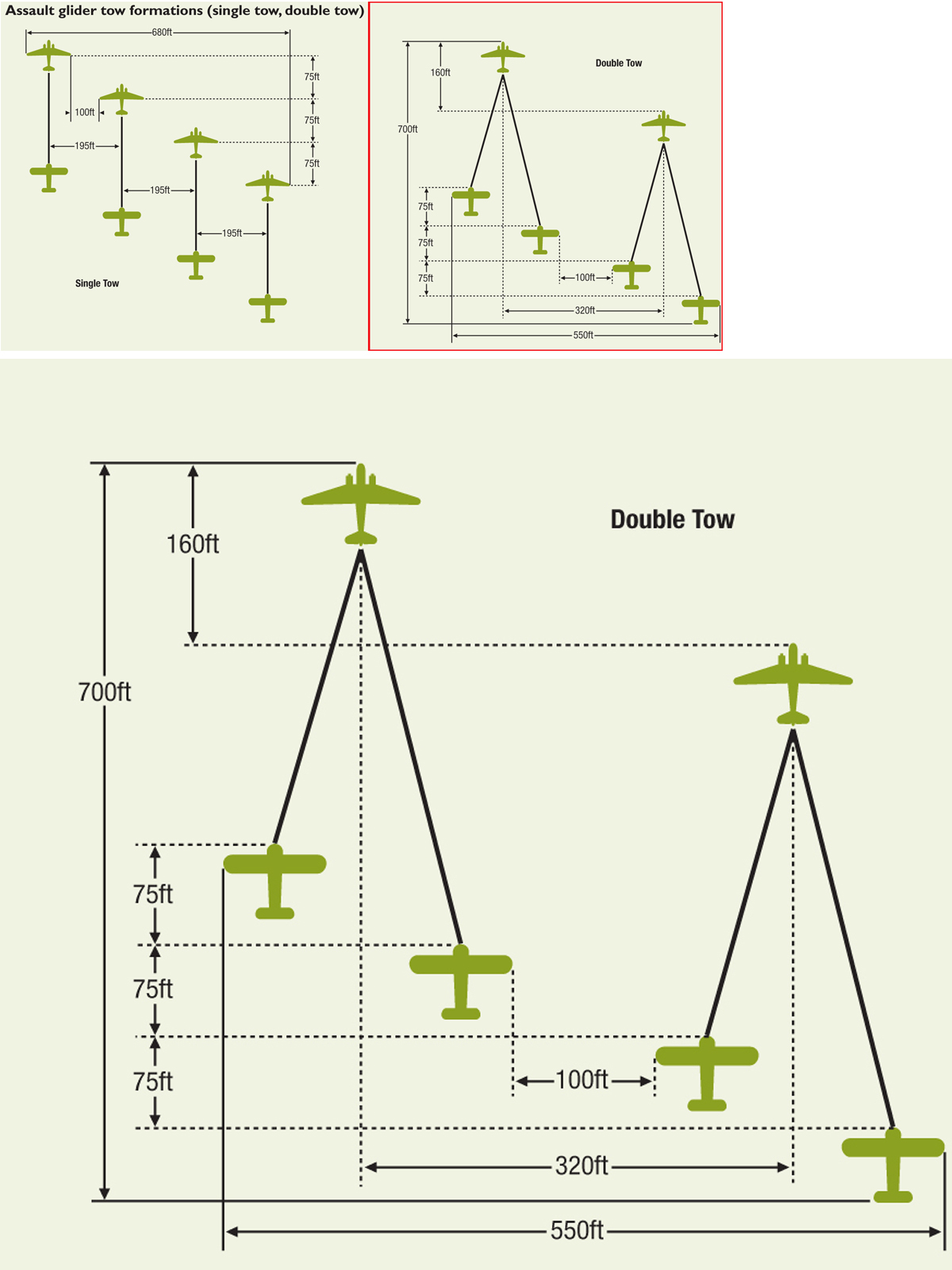

During airdrop missions, the standard aircraft tactical formation was called a “serial,” which was a formation of aircraft assigned to a specific drop zone (DZ) for paratroops or a landing zone (LZ) for gliders. Serials varied in number of aircraft; pathfinder serials were quite small, usually only three aircraft. The standard paratrooper serials were larger, typically 36–50 aircraft, or about four to six squadrons.

The distance between the tug and the glider complicated glider missions. Although the C-47 was capable of a double tug of two CG-4A gliders, this was hazardous at night and was not used until Operation Varsity in 1945. Some serials on D-Day were mixed paratrooper/glider missions; for example, when delivering paratrooper units with heavy equipment such as artillery and jeeps.

Doctrine called for glider pilots to be evacuated as soon as possible after the airborne landings as they were not regularly trained for ground combat. These glider pilots have been collected aboard an LCVP for transfer back to airbases in Britain following the D-Day landings in Normandy. (NARA)

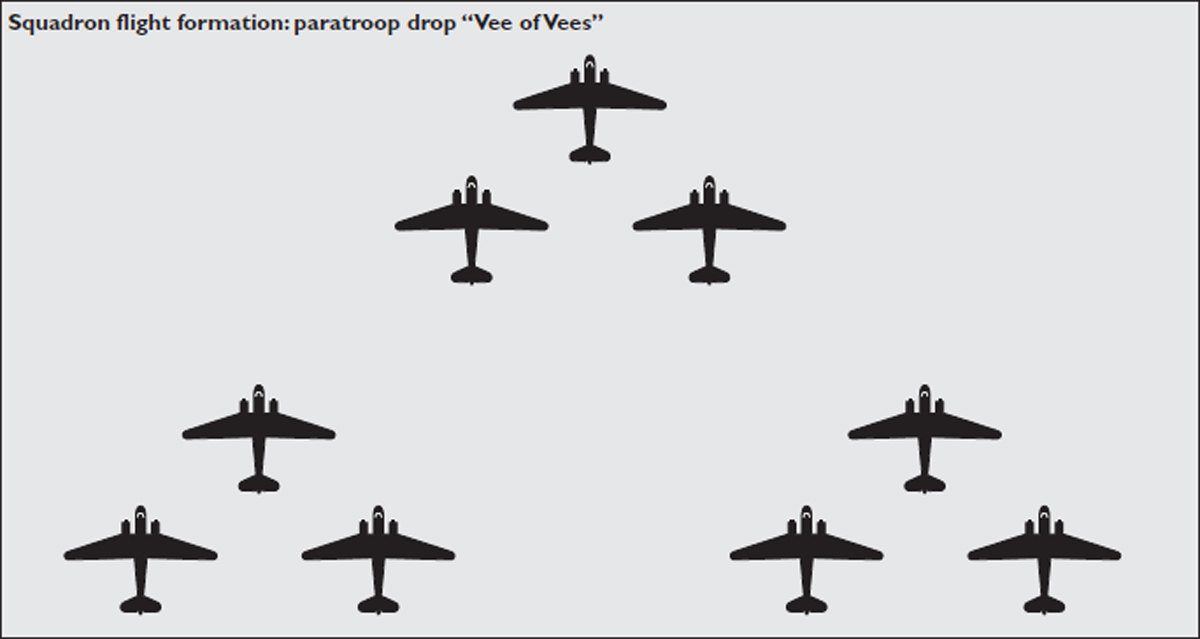

Although each troop carrier squadron had 12 operational aircraft, the general practice was to employ nine per mission. This was linked to the standard formation of a “vee-of-vees” with each flight of three aircraft in a “V” formation and each of the three flights in turn forming a larger “V.” The “vees” were staggered slightly upward behind the lead aircraft and the trailing “vees” upward of the lead “vees” to prevent paratroopers from hitting following aircraft when they jumped.

| IX Troop Carrier Command Brig. Gen. Paul Williams | |

| 1st Pathfinder Group (Prov) | 1st PFS; 2nd PFS; 3rd PFS; 4th PFS |

| 50th Troop Carrier Wing Brig. Gen. Julian Chappell | |

| 439th Troop Carrier Group | 91st TCS (L4)*; 92nd TCS (J8); 93rd TCS (3B); 94th TCS (D8) |

| 440th Troop Carrier Group | 95th TCS (9X); 96th TCS (6Z); 97th TCS (W6); 98th TCS (8Y) |

| 441st Troop Carrier Group | 99th TCS (3J); 100th TCS (8C); 301st TCS (Z4); 302nd TCS (2L) |

| 442nd Troop Carrier Group | 303rd TCS (J7); 304th TCS (V4); 305th TCS (4J); 306th TCS (7H) |

| 52nd Troop Carrier Wing Brig. Gen. Harold Clark | |

| 61st Troop Carrier Group | 14th TCS (3I); 15th TCS (Y9); 53rd TCS (3A); 59th TCS (X5) |

| 313th Troop Carrier Group | 29th TCS (5X); 47th TCS (N3); 48th TCS (Z7); 49th TCS (H2) |

| 314th Troop Carrier Group | 32nd TCS (S2); 50th TCS (2R); 61st TCS (Q9); 62nd TCS (E5) |

| 315th Troop Carrier Group | 34th TCS (NM); 43rd TCS (UA); 309th TCS (M6); 310th TCS (4A) |

| 316th Troop Carrier Group | 36th TCS (6E); 36th TCS (W7); 44th TCS (4C); 45th TCS (T3) |

| 53rd Troop Carrier Wing Brig. Gen. Maurice Beach | |

| 434th Troop Carrier Group | 71st TCS (CJ); 72nd TCS (CU); 73rd TCS (CN); 74th TCS (ID) |

| 435th Troop Carrier Group | 75th TCS (SH); 76th TCS (CW); 77th TCS (IB); 78th TCS (CM) |

| 436th Troop Carrier Group | 79th TCS (S6); 80th TCS (7D); 81st TCS (U5); 82nd TCS (3D) |

| 437th Troop Carrier Group | 83rd TCS (T2); 84th TCS (Z8); 85th TCS (9O); 86th TCS (5K) |

| 438th Troop Carrier Group | 87th TCS (3X); 88th TCS (M2); 89th TCS (4U); 90th TCS (Q7) |

| * Alpha-numeric code after each squadron is the squadron code painted on the nose of the aircraft. | |

Within each serial, the paratroopers within each aircraft were called a “stick.” The size of the sticks varied, usually 18–20 paratroopers per aircraft in most C-47 transports, but only nine to ten in parachute artillery units due to the amount of other equipment carried in the para-packs that were dropped with the stick. Likewise, the number of troops per glider varied depending on the combat load. The CG-4A glider had typical loads of two crew plus 13 glider infantry; or a jeep and four troops; or a 75mm howitzer, three troops and 18 rounds of ammunition. The Horsa glider had a standard load of two crewmen plus 28 glider infantry; or two jeeps and crew; or one 75mm pack howitzer plus jeep and crew.

A critical technical and tactical problem faced in the early airborne operations was the difficulty of navigating transport aircraft at night to provide precision airborne delivery of the paratroopers and gliders. This was due to the relative immaturity of night navigation technology. The RAF had pioneered night navigation both for night bombing missions and the air delivery of supplies to resistance groups in France. The preferred British approach was to use Gee, a radio navigation system deployed in 1943 to assist RAF night bombing. Three British radio stations emitted a coded radio pulse that was monitored by the navigators on the transport aircraft who then used triangulation to determine their position on a map. The system was optimistically rated to have a margin of error of 1,200ft, though some experts believed it was closer to 2,000ft in range and 1,500ft in deflection. The system was vulnerable to German electronics jamming that could blind it for up to 15 miles from the jamming station. The first Gee set was mounted on a USAAF C-47 in January 1944 and, prior to D-Day, there were plans to fit 108 aircraft with the full set and 44 others with a partial set. The problem with adopting Gee was two fold: on the one hand there were not enough sets to go around; and, on the other hand, IX Troop Carrier Command was desperately short of navigators, with only about one for every three aircraft. In contrast, the smaller British transport force had a trained navigator for each aircraft.

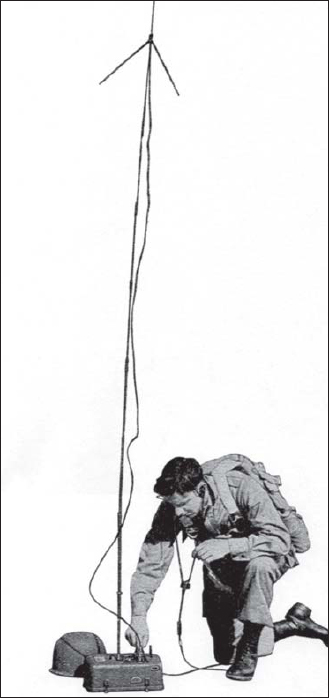

The key task of the pathfinders was the delivery of the Eureka beacon to the drop zone to serve as a navigation aid to the main airborne landings. This is the standard AN/PPS-2 version of the Eureka in the deployed configuration. (MHI)

As a result, IX Troop Carrier Command favored the Rebecca-Eureka system that had been used with some success in the Mediterranean. This system had originally been developed in Britain to assist in delivering supplies to the French resistance. The Rebecca was an airborne radio transponder that worked in conjunction with a ground-based Eureka radio beacon. The Rebecca activated the Eureka by coded radio pulses, and the Eureka beacon responded with the signals being acquired by Rebecca antennas on either side of the forward fuselage of the C-47. The signals helped the crew determine whether the drop zone was to the right or left. The US began manufacturing the Eureka Mk. IIIC in 1943 as the AN/PPN-2 beacon transmitter-receiver. The Eureka-Rebecca system was not particularly reliable at close range due to potential interference from the multiple beacons, so it had to be supplemented by some other device to inform the transport crew when they were over the drop zone. The method for night drops was the use of special holophane Aldis lights set up in a T pattern 30 yards long and 20 yards wide with the Eureka positioned 25 yards beyond the head of the T. To distinguish different drop zones, different colored lights were used.

The performance of the Eureka-Rebecca system depended on planting the Eureka and the associated lights accurately within the intended drop zone. This was the task of the pathfinders, an elite team in each airborne division delivered to the drop zone by special pathfinder squadrons from IX Troop Carrier Command.

Prior to the D-Day landings, a variety of improved navigational aids were being deployed. The new SCR-717 was an early form of ground-scanning radar and could help the navigator identify when the aircraft had passed over the coast due to the different radar reflectivity of water and ground; however, it was fairly useless over ground for navigation purposes due to backscatter. Shortly before D-Day, the BUPS responder beacon was developed which worked somewhat like Rebecca-Eureka in providing a blip on the radarscope when interrogated by the SCR-717 radar. Only about 50 SCR-717 radar sets were available at the time of the Normandy landings and flight leaders primarily used them, with the BUPS being planted along with Eureka.

These tactics for night drops had some serious weaknesses. The pathfinders could not be dropped too soon or their discovery would alert the Germans to an airborne attack; if dropped too late they would not have time to establish their beacons. As would become apparent during the D-Day missions, the pathfinders had considerable difficulty positioning their equipment in time. The accuracy of the drops was further undermined by the reliance on serial formation tactics due to the shortage of navigators. If the serial was disrupted by clouds or flak, the individual aircraft faced considerable difficulty in accurately locating the drop zone when lacking a navigator with the Gee navigation aid. The British approach was to use looser formations since all transport aircraft had a navigator and the Gee equipment, and so could navigate independently in the event they were scattered by weather or flak.

The navigation problems and resultant dispersion of the paratroopers during the D-Day drops severely compromised the ability of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to carry out their missions. The technical shortcomings of the existing navigation technology convinced the First Allied Airborne Army to drop the idea of massed night drops. All major airborne drops after Operation Neptune were conducted in daylight. The presumption was that German flak positions could be suppressed by Allied airpower and that losses and disruption caused by flak would be less serious than problems induced by nighttime navigation issues.