STRIDE 1

Stagnancy & Paralysis

The feeling: “I feel trapped. I feel stuck. I don’t want to stay here, but I don’t know how to make things better. I don’t even know if it’s possible.”

I was thirty-three years old at the time. There I was, a Recon Marine, the best of the freaking best, the toughest of the tough, trained to survive the most death-defying missions, trained to trained to survive the most death-defying missions, trained to gather intelligence against all odds, trained to be a professional killer, and I felt like a scared, traumatized little boy. I wanted to hide under a table. I wanted to hide from the icy despair in my stomach. I was frozen with the feeling that the whole universe was pressing in on me, crushing me with shame and fear. I felt totally powerless. Was it the sniper missions? The close air support missions? The insurgents in Fallujah? The bloody fights for my life? No. It was my marriage. It was falling apart.

I had survived the arduous training grounds of reconnaissance indoctrination—a training regime so elite and intense eighty percent don’t make it. I mastered every skill for amphibious raids, underwater demolition and infiltration, weaponry, surveillance, intelligence, scuba, paratrooping, hostage survival, and escape. I survived one tour in Afghanistan and two tours in Iraq. But I did not have the preparation or the experience to survive a divorce.

I can remember being underwater in Combatant Diver School where I held my breath for three minutes while a team of Recon Instructor Sharks simulated a violent attack.That I understood.That I could survive. But on the day I realized my marriage was ending, I was gasping for air. Completely ambushed.Totally destroyed.

In hindsight I can see how my marriage was unraveling long before the divorce. I had entered Recon training at twenty-six, already married. For the next seven years our relationship consisted of a few days or months together. Then I would be gone for long periods of time in training missions and ultimately in combat. During my first deployment to Afghanistan I couldn’t get my wife out of my head. I missed her. I hurt to be with her. I was walking around like a zombie. My team leader, a rangy, tough mountain man from North Carolina, saw me writing a letter to her. “Get your head out of your hole,” he warned. “I didn’t invest all this time in you to have you end up a turd. Put that crap down. It will be waiting for you when you get back. Right now we got business to handle.” I don’t fault him for that. He was right. If you’re not focused, you die. So I poured my energy, my devotion, everything I had into my recon platoon and our missions. I was fighting the hardest fights of my life. I fought for my team. Some of them died for me.You can’t put a language to the bonds you forge when you’re responsible for people’s lives.

Duty is a slippery thing. It can save lives but it can also kill a marriage. Everything I was going through in my job I was going through for both of us. But she needed more. I needed more. We needed our connection. It’s sad to me that neither of us knew how to really talk and support each other. It was tragic to me the day I had a chance to phone her from the field to only have bombs suddenly coming in from the enemy with loud explosions blasting in the background of the call. She could hear the sounds of war over the line and started distressing, “Baby, what is that? Are you okay? What’s going on?” I could hear the worry in her voice and it troubled me to hear her upset, so right then and there I decided to not call her anymore. I told her I had to go, there was business to handle. I hung up the phone and let go of our connection.

And so I did my duty. I worked hard and sent home a paycheck. Every time I came home on leave, there was more and more distance. And so I’d return to combat, do my duty, and keep sending paychecks. Seven years later, by the end of my final tour, I was empty—emotionally, mentally, sexually, and spiritually. I had nothing to give her. And she had nothing to give back. I had grown to hate the cage that had become my marriage and I blamed myself for its failure.The battles on the field were now being mirrored by the battles in myself. I was unhappy, depressed, and in shock. I kept thinking, “It’s my fault, I don’t deserve anything better.”

All the traumas and betrayals of my youth were exponentially magnified by the trauma of losing my marriage and the traumas I experienced in battle. I was already fractured on the inside. I had worked hard in my career to make something of myself.To glue the pieces back together. But those fractured pieces turned to powder when my marriage dissolved.

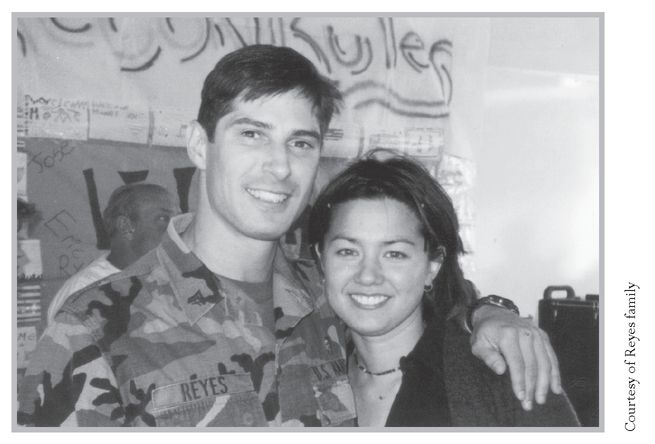

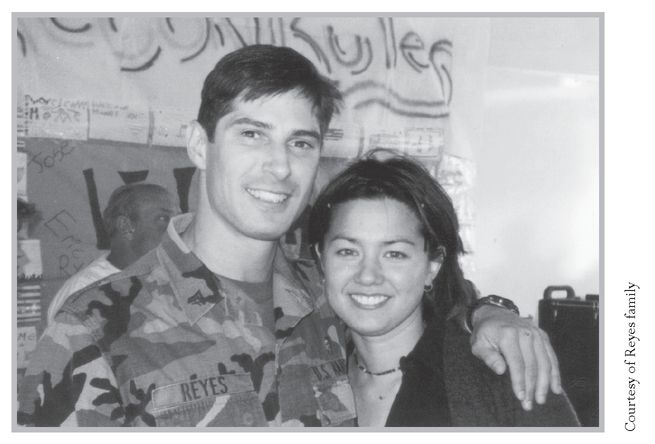

With my wife while in the U.S. Marine Corps.

Even though I was thirty-three years old, a grown man and an elite warrior, I felt eleven again. I felt like the little boy who was molested twenty-two years earlier by a family friend—the little boy who was being used and disposed of; whose very essence was being assaulted; who felt blown into a million worthless pieces; who paced the cage of his life in shame and fear; and who wondered: Is it too late for me? AmIalost cause?

Honestly, I felt I wanted to die. I felt doomed to a futile existence. Trapped in stagnancy and paralysis.

If there’s any sentiment that sums up stagnancy and paralysis, I think it’s simply this: “I don’t know who I am, I don’t know what I want, and I don’t know where I’m going.” That’s how I felt.

Your Story is My Story

It doesn’t matter whether the facts of our stories are similar or different, everyone can relate to the crushing demands of family, duty, career, relationship, money, and surviving day-to-day. Many of us can relate to the terror of childhood neglect and abuse. And most of us can relate to periods when we’ve felt lost, afraid, alone, and worthless. Wherever you’re at in life today, if you feel any amount of stagnancy and paralysis, I hope you can feel me when I say, “I’m with you.” I know it’s big. I’ve been in the same muck and mire. I know it feels insurmountable. But believe me, it’s not. If my story is your story you can move. If stagnancy and paralysis is integral to the hero’s journey you can rattle the cage.You can take a tiny step, utter a new word. If I can do it, you can do it too. I’m not talking about coping. Coping is acceptance of the cage. It may keep your heart beating and your lungs breathing, but it’s not life. It’s resignation. It’s not Hero Living. No, I’m talking about dismantling the cage bar by bar. I’m talking about tuning into your feelings. I’m talking about telling yourself the truth. I’m talking about coming to know who you are, what you want, and where you are going.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the Russian author, philosopher, and forerunner of existentialism, said,“Taking a new step, uttering a new word is what people fear the most.”When we feel trapped, caged, imprisoned, stuck, or mired in quicksand, we’re in fight or flight. Sometimes the fear manifests as a steady anxiety, a continual insecurity we can’t seem to shake. But sometimes the fear is so primal and raw that movement of any kind feels life threatening. Either way, we desperately want out of our situation, but it can feel unachievable, even death defying, to consider anything but the bars to our cage. To use an old idiom, it really is a living hell.

Some of us resign ourselves to this hell.We can’t see a way out no matter how hard we try. Some of us think we deserve it, as if we have to pay some kind of penance. And some of us get so used to the cage we don’t even know we’re in it.

Stagnancy and paralysis can be disorienting because of its ability to sneak up and ambush us. Before we know it we can’t remember the dreams we used to dream; we can’t put a finger on why we’re so angry; we can’t make sense of our unhappiness when we have so much; we can’t let go of past traumas and regrets; and we can’t figure out why life keeps dealing us blow after unfair blow.

Some philosophers call this an existential crisis—the point at which our life feels lost; our obstacles feel insurmountable; our day-to-day responsibilities feel pointless; and the meaning of our life feels purposeless.You may not relate to all of this, but if your lungs are breathing, your heart is beating, and your neurons are firing, you can relate to some of it.You are a human.You are a hero. And we heroes know a little something about hell.

Think about Sisyphus. Poor Sisyphus. What a life. The gods in this iconic Greek myth really did a number on him. They weren’t particularly charmed by his overweening pride and cockiness, so they cursed him. He now spends eternity pushing a massive boulder to the peak of a steep hill, only to have it mash over his toes and roll down to the bottom. He dutifully descends, bloodied and bruised, to start the uphill battle all over again, day after week after year after eon.Talk about stagnancy and paralysis.Talk about a loop of suffering. Talk about hell.

Whether Sisyphus deserves this punishment or not is a whole other book that has nothing to do with Hero Living. In Hero Living there is always the possibility for freedom. Always the loud quiet call to move into the next stride. But Sisyphus doesn’t know this. He doesn’t know he has made a silent agreement with his circumstances, a dead-end pact with his suffering. So he fixates on his obstacle; he obsesses over the damage it has done to his life; he wallows in the pain of his broken back and broken spirit; he replays the innumerable times the boulder has hurt him; he regrets every uphill attempt and sees only the downhill failures; he resigns himself to the boulder and, in the process, forgets what he loves and dreams. He forgets who he really is and squelches the loud quiet call within.

Albert Einstein is credited for saying, “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again but expecting different results.”

Who hasn’t experienced this insanity at some point in their life? More accurately, who doesn’t make and unmake their own Sisyphean agreements day in and day out? I certainly do and, my guess is, you do too.

The Sisyphean Agreement as It Applies to Real Life

Life can throw us some serious blows.The traumas we survive, the hardships we’re in the middle of right now this very moment, wow—the stuff we endure. At least my man Sisyphus knows exactly what he’s dealing with. He doesn’t get ambushed day in and day out with a new set of problems. No bills to pay. No career to create. He’s not raising kids or trying to make a relationship work. There’s no cultural system telling him what to believe. He’s not jockeying for a position in the world. He doesn’t have body issues. He wasn’t neglected or abused as a child. Comparatively speaking, when you think about it, a boulder ain’t so bad. At least it’s just one problem to worry about instead of a stormy confluence of many. It’s this superhuman juggling of life that makes me proud of the heroes I get to meet and work with every day.

One of the great opportunities of my life is training fellow heroes just like yourself in my fitness program. They may see themselves as average people, but I see them as courageous standup warriors who have heard the loud quiet call inside and show up for an hour to push beyond their stagnancy and paralysis.You can bet we whoop it on. It’s a total mind, body, and spirit overhaul. At the end we’re so transported by the journey, so drenched in sweat, it’s like a baptism into new possibilities. Imagine that experience three times a week—three baptisms into new possibilities.

One of my fellow heroes in fitness is Kim, a soulful forty-year-old woman who has been haunted by low self-esteem her entire life. Kim told me, “I’m not really sure why this has been such an issue for me. I grew up with a lot of friends, I excelled in school, and I had a family that supported me. But I always compared myself to others. I weighed more than my friends. I stressed about being successful in my job. And I was afraid of not being accepted. I just never felt good enough for anyone. And I kept asking myself a question I could never answer, ‘Good enough for whom?’ ”

Another friend, Lee, a successful advertising executive, told me about his particular brand of stagnancy and paralysis. “For years I split myself into different roles—husband, father, executive, son, and churchgoer. I was parsing out my life force like currency and so I really wasn’t able to show up one hundred percent in anything I did. No wonder I felt zapped all the time. No wonder I didn’t take the opportunity to play, to have fun, to do the things I really love to do. It’s a new idea to show up authentically as myself in everything I do.”

My hero sister Madeline felt trapped in her marriage. The pain caused by an unfaithful husband drove her into despair, which resulted in gaining a lot of weight. “My weight protected me so I couldn’t be hurt anymore. For a while I thought if I got fit, it would be a sign I was moving on. It would be my way of forgiving him. But moving on wasn’t ultimately about losing the weight. It was about me wanting more for myself. Until I got that, I was stuck.”

My man Geoff, a consultant and fellow warrior in Hero Living, spent years on a roller-coaster ride with money. His mother was single when he was born, raising three kids on just $200 a month. When his mother married a multimillionaire, Geoff’s identity shifted from a poor kid to a rich kid. Then in his mid twenties his stepfather lost it all, including Geoff’s inheritance. Geoff describes his relationship with money as a turbulent one. “Money took on a kind of abusive energy metaphorically. Sometimes it was good to me, sometimes it wasn’t. I thought it had an agenda for me and so I distrusted it. I unconsciously looped in that space for fifteen years. Money would show up and then disappear, show up and disappear. Talk about a cage.”

We all have a story. In fact, most of us have several stories going simultaneously, each one a seemingly immovable bar in our cage. The problem with our stories is they’re not very supportive of what we really want. They keep us afraid, disoriented, and feeling alone. Sometimes they can even play mind tricks on us. Take the mom who works so hard to be the most amazing mother ever.Who loves and supports her kids in every way but somewhere along the line loses her sense of self. Or the son or daughter who, regardless of how hard they try, always feel like a disappointment to their parents. Or the mother or father who goes off to work to support their family but is disheartened because they feel so disconnected from the people they love the most. Duty without passion, responsibility without getting your needs met, soon turns into resentment and guilt—a big cage for many of us.

Growing up, I read and reread all the books in the Frank Herbert classic science fiction saga Dune. In the first book he set down the Litany Against Fear. I love the word “litany.” It is by definition a prayer—a recurring invocation for courage and purpose. How beautiful it is to have a prayer that invokes possibility for more life. If you know the book, you know the character Paul Atreides intones the litany when the Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam challenges him to a test. This test employs severe physical pain in order to prove Paul’s humanity. What’s interesting is that Atreides’ petition isn’t one against pain, even though he knows that intense pain is part of the approaching ordeal, instead his supplication is to turn his attention to an even greater threat. Fear.

As a basic survival mechanism, the emotional response of fear can serve to keep a person safe from immediate danger. But fear can have a way of taking hold, of tacking on past the point of needed protection and billow into nervous panic or paranoia, or it can seep in with a numbing power to slow the pace or stop a person dead in their tracks, to mesmerize and overwhelm. It is in such moments that fear crosses over from a helpful guardian into an enemy and destroyer of the mind and dreams. In voicing the Litany Against Fear the petitioner opens to possibility with the words:

“I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path.”

Inferred in this prayerful prose is that our cage can be opened and we can be set free, and in seeing the wake of fear’s path, we find ourself revealed. It could be said our stagnancy and paralysis work the same way.The truths that are hidden in our pain are, in fact, the keys to our freedom. In other words, if Herbert is right, if facing my fears, if permitting them to pass over me and through me, is the key to freedom, then the possibility of opening the cage door is available every moment. Now. And now. And now . . .

How exactly? The key to the cage door is right in front of me, right inside me, and it’s described in those transformative words, “the inner eye.”

The French archaeologist and historian Paul Veyne said, “When one does not see what one does not see, one does not even see that one is blind.” What power this statement has.When I fully grasp the truth that everything I need is inside me, my inner eye instinctively begins to look. And search. And seek possibilities. New questions then invite me into new ways of seeing. And I consider: What feelings have I refused to acknowledge? Why do I allow myself to be treated poorly? What do I get out of staying attached to the past? Why am I so afraid to make a change? What would a better life feel like? Why do I agree to situations that aren’t good for me?

Go looking for your truths, my brother and sister. Use your inner eye to seek, to find, to excavate, and to reveal.Your inner eye is your hero’s eye. It will never lie. It will never betray. It will always lead you stride by stride through the hero’s journey. Use your inner eye to go looking for your truths and then name them. Identify them. See them for what they are. What you’ll find is that, in time, the frozen lock to your cage loosens.The truths you identify become your keys to newfound freedom. And the cage itself dismantles and dissolves. As Herbert says in the Litany Against Fear, “Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.”

THE HERO’S WHETSTONE: TUNING IN

As I mentioned in the introduction, throughout this book I will be providing contemplative prompts for you to take stock in your life; to tune in to your mind, body, and emotions; and to give full attention to your hero within. As a reminder, remember to start with yourself just as you are, right now, this moment. No judgments. No apologies. The value of these prompts is the powerful information you will get about yourself. Whoever said, “Ignorance is bliss,” I guarantee you they were not in bliss. They were in stagnancy and paralysis. Lack of knowledge about your self is the cage. Information about your self is the key.

Why do I call these contemplative prompts whetstones? I began my studies in Shaolin kung fu when I was eighteen. As you can imagine, the warrior philosophy of the Oriental martial arts corroborated everything I had learned from my comic books heroes and from my hero of heroes, Bruce Lee.The whetstone I reference is what the twelfth-century samurai used to sharpen their sword. As taught in the Bushido, the samurai’s code of conduct, the sword represents the soul—the authenticity, strength, and power of the soul. So the whetstone is the means by which the samurai sharpens his or her soul so they can cut to the truth. Use the Hero’s Whetstone throughout this book and the truths of your life, your power, your authenticity, your dream, and your destiny will begin to reveal themselves. They just will.

As we move through each whetstone, you may find it helpful to keep paper and pen at hand. It’s not necessary, and it’s up to you, but you may find power in seeing words on paper versus just in your head, something that could make a difference to your journey. If this resonates with you, take a moment to gather your writing tools.

Now, before we begin with the first Hero’s Whetstone, take some deep breaths. Before you read on, take a few moments to give your full attention to your breathing. Take three deep inhales through your nose and three full exhales through your mouth. Go ahead. Breathe life in and out for three moments.

As you sit in the breath of life, think of a friend. Think of how you sometimes see them struggle or stumble along life’s path.When they do, see how you support them. With a listening ear, kind advice, compassion and understanding, sympathy, a hug, or perhaps even telling them like it is when needed. Now consider whether you give yourself as much compassion, understanding, sympathy, and empathy when you see yourself struggle and fall. Generally, I believe it’s most common that people are more generous and kind with others than they are with themselves.

So this is an important aspect to consider in moving through each Hero’s Whetstone prompt. As you contemplate each one, I want you to do so while seeing yourself not as you, but as a good friend. To the extent that you can, detach and see yourself from a friendly, compassionate, forgiving, empathetic, kind, and wise, outside perspective. Even if you must pretend like a child would, be an unbiased third-party observer to your self. And one that loves you.

So now with your friendly self and perspective intact, let’s begin. This first Hero’s Whetstone starts with a question: As you scan the list below, what feelings do you resonate with most? What feelings best describe what you’re going through right now? Don’t overthink it. Just note what feelings you identify with. Be careful not to judge or justify, to excuse or deride. Just tune in to your feelings.That’s all you have to do.The samurai’s whetstone is never abrasive. It doesn’t have an agenda for the sword. It works with the sword just as it is. It’s the same with the Hero’sWhetstone. It works with your soul just as it is. So be honest but be gentle as you scan the list below.

Right now I feel . . .

Disappointed in my life

Angry all the time

Caged by my responsibilities

I’m never enough, no matter how hard I try

Ashamed of my body

Neglected by my partner

Generally okay, but I want more

Afraid people will see how vulnerable I am

Everything is my fault

Controlled by my addiction

Physically exhausted and emotionally spent

Trapped in a passionless relationship

Guilty about things I’ve done in the past

Sexually undesirable

Stuck in a dead-end job

On top of the world

As if something important is missing, but I don’t know what

Unresolved about my past

Like I’m coasting along in a rut

Betrayed by those I love

Worried and stressed all the time

Fully satisfied

Embarrassed for being unhappy, given everything I have

Like my childhood was taken from me

Powerless to make a change

Totally alone

Like I can’t be myself and be loved

That I never have enough money

That I don’t deserve success

The constant pressure to be superhuman at everything I do

Trapped by the traditions of family and/or religion

As you scan this list, be sure to note any additional feelings that come up. As you identify the feelings you resonate with, whether on the list or not, the first thing to remind yourself is that you are a human. The second is that you are a hero. All feelings, whatever they are, can be integral to the hero’s journey if you will work with them. They can be clues to the bars of one’s cage. How intensely you feel is an indicator of how stagnant and paralyzed you are. I want to be clear this is not bad news about your self.This is, in fact, brilliant transformative news. Because in identifying your feelings, in using your truth-saying whetstone to give voice and attention to what is trapping you, you begin to rattle the cage. And the hero within begins to wake up.

The Silent Agreement

When you think about it, an agreement is basically a pattern. For example, if we make an agreement at work, we agree to a certain pattern of thought and behavior. When we partner with someone, we agree to a specific pattern in our relationship. It might be healthy or it might be dysfunctional, but we agree nonetheless. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be there. The same applies to any of the agreements we make day in and day out, whether it’s with our emotions, our bodies, and our spirituality, or whether it’s with family, friends, career, religion, or culture.We agree to certain patterns of thought and behavior every moment of every day. The question is, using your inner eye, “Are you conscious or unconscious of the agreements you are making?”

Consider the fairy tale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” written by the Danish poet Hans Christian Andersen. Talk about a silent Sisyphean agreement made first with himself as emperor and then with his dutiful kingdom. Remember the unspoken agreement they all have? Clothes matter most. So when two swindlers promise the emperor the finest suit made of invisible cloth, he pretends that he can see the suit. As do his ministers. As do his people. Everyone agrees to this pattern of thought and behavior as he marches in a procession amongst his throng of adoring people. Except for one child. It’s the child, the pure, guileless truth-saying symbol for the inner eye, who simply declares, “He has nothing on.”

Silent agreements are the bars to our cage.They are set patterns of thought and behavior we have agreed to, sometimes consciously but oft times unconsciously. The boxing trainer and commentator Teddy Atlas actually coined the expression, “Silent Agreement.” He used it to describe the moment when two boxers hold on to each other and silently agree not to fight. For fear of being knocked out, for fear of fatigue, for fear of the unknown, both agree to trap themselves and each other. Or, to phrase it in terms of Hero Living, they both agree not to move. They are stagnant and paralyzed in a set pattern of thought and behavior. Nothing is possible until one of them breaks the silent agreement and frees not only himself, but the other. Now, anything is possible. Regardless of who wins, both are winners because both are free to move.

In Dune: House Atreides, by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Ander son, we are reminded, “The worst sort of alliances are those which weaken us.Worse still is when an Emperor fails to recognize such an alliance for what it is.”

You are emperor, warrior, hero, and sage of your journey.Your inner eye is your truth sayer. And Hero Living is your compass, your mirror, and your lantern. If you are willing, now’s the time to look honestly at your silent agreements; to recognize your alliances for what they are; and to see what your cage is made of bar by hidden bar. Of course, you will want to hang on to the agreements that support and inspire you. It’s the agreements that weaken and entrap you that I’m interested in.

THE HERO’S WHETSTONE: USING YOUR INNER EYE

I love the fact that it’s a child that frees an entire kingdom in “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Some may choose to ignore the truth and continue their silent agreement. But those who listen and consider will be forever changed. Your inner eye is akin to the way a child tells the truth. A child isn’t judgmental, coercive, or ashamed. A child just tells it like it is—as information, as fact. The biologist T. H. Huxley describes it this way: “Sit down before fact like a little child, and be prepared to give up every preconceived notion.” That’s it. That’s all you have to do. Just go looking for your truths. Get them out on the table. Name them. Identify them. Own them. Scream them if you have to. But whatever you do, don’t resist them. See them for what they really are. Simply information you can use to pick the lock of your cage, to set yourself free, and to create something different. The truths of your suffering cannot survive the light of your awareness—the brilliant, transformative, childlike gaze of your inner eye.

If this truth saying process sounds magical, it’s because it is. There will be plenty of things for you to do later on in your hero’s journey. But for now, in this stride of stagnancy and paralysis, all you have to do is engage your inner eye and tell yourself the truth with childlike candor.That’s it.That is enough because you are enough.

So are you ready for your next Hero’s Whetstone? I’m here with you, by your side.You can do this. Let’s sharpen your soul—your authenticity, strength, and power. Start with your breath. I will be asking this of you often. Breath is life. Breath is movement. Breath relaxes and grounds. So tune in and take three deep inhales and then three full exhales.

Now, I’m going to invite you to engage your inner eye. This is the hero’s most powerful tool for exposing the silent, Sisyphean agreements you have made with your suffering.Without judgment, let’s go looking for your truths. You can answer the following prompts in whatever way you want. The important thing is that you take the time to really consider and that you allow any and all information to reveal itself.

1. Given the list of feelings you considered earlier in the chapter, which ones did you resonate with most? Which ones did your body and emotions have the strongest response to?

2. Which of these feelings have become the hidden bars to your cage? As you contemplate this, are there any new feelings that come up? Are there any new bars your inner eye is seeing for the very first time?

3. Now turn your inner eye to each bar of your cage.What is your silent agreement with each bar?What is your pattern of thought and behavior associated with each bar? What do you get from the agreement? How do you benefit from keeping a silent agreement with each bar?

4. Now that you see your cage bar by bar, agreement by agreement, what does your cage look like? What form does it take? Get a vivid image in your mind’s eye.What material is the cage made of? How many bars are there? Is there a lock or a combination? What are you doing in relation to the cage? Are you curled up in the corner? Pacing? Shaking the bars? Climbing? How long has the cage been with you? When did the cage get built? Who built it? Let your imagination go and create a vivid image of the cage and your relationship to it.

5. Now that you have tuned in to your feelings, identified the bars of your cage, exposed your silent agreements, and have a vivid image of your relationship to the cage, consider this: What’s the one thing you could do right now that would make the biggest difference in your life?

Seeing the Cage for What It Is . . . Is An Act of Freedom After the third day of no sleep and over a hundred pounds on my back on the last few days of grueling patrol week in the Amphibious Reconnaissance School at A.P. Hill, Virginia, I was faltering. I felt a horrifying desire to give up. I boosted my courage by volunteering for a mission in an icy river but I failed that assignment, and upon failing I was sent into the mental numbness of severe hypothermia and spiraled into sluggishness and the black-hearted terror of being found out as a quitter.

Inside, I knew I had quit a lot of times as a boy. Not long after my grandmother had passed away, my gifted and talented fourth-grade teacher and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. Gordon, started reaching out and took me under their wing. I didn’t know it at the time, but I imagine she could see that my home life was falling apart and for whatever reason they were compelled to extend their loving help. I used to spend a day on the weekend with them listening to music and going to the museum and building model rockets.

Then at some point I found out the news that Mom was planning to move my brothers and me to my uncle’s home in Dallas. Mom felt Grandma had quit on her by dying, and now Mom was quitting on herself and on my brothers and me, and sending us away. I felt punched in the gut with the wind despondently knocked out of me as uncared for and unwanted. The thought of being sent away, leaving my home, of leaving my school and others I loved just crushed me. I thought of the Gordons and really wished they could have been my parents in those moments, but I felt they didn’t deserve to have a child so unwanted as me. I figured I should just quit.

And so on the inside, I did. I didn’t even say good-bye.

I stopped going to the Gordons, and about a week before the road trip to Texas I stopped going to school. I just stayed in my room during the day while my little brothers were at school and Mom was downstairs watching her TV programs checked out in the haze of marijuana and the grief of the loss of her parents. I sat in my room and silently cried. I didn’t even hang out with my best friend Sean Blakemore anymore. I just quit.

So that same kind of quit was creeping and bubbling up from me as my proud body was being destroyed by Amphibious Reconnaissance School. On the fifth day of constant operations I started to hallucinate images in my heart not in my head. I felt as though I was being lost in a wave of Marines a thousand strong and I was completely insignificant. I felt unimportant and not needed. I was certain the stink and rancor of quit was all over me and that my teammates could smell it. The weight of my ruck felt like a thousand pounds, but the weight of my heart and its regret seemed a million tons. The ruck straps cut into my clavicles and trapezius like razor wire, but it was nothing compared to the naked shame I felt.

There at the root of my drive and success was the black kernel of fear and shame, the agreement that I was a coward and weakling for what I had done in the past. As a mechanism for coping, duty and its bedfellows of discipline and power had helped me overcome the darkness of my most broken and vulnerable child self, but the drawback was that if I was not fighting forward or accomplishing missions, my confidence waned. My center of strength and light faltered.

My duty as a warrior and protector gave me that continuous impetus to accomplish and quest. So I built my body and the strength of its muscle as part and parcel of this duty. To make myself attractive to not be thrown away. To make myself strong to repel the enemies’ assault. To be exceptional to mask my shame of cowardice. I felt my savior would be my accomplishments and accolades, but underneath the armor and weapons I felt myself a coward and a weakling. And for some reason I could not understand that it’s completely normal to be hurt and angry and feel paralyzed with fear as a seven-year-old boy being tossed as litter to the wind. In my heart I didn’t understand it wasn’t my fault that my mom had quit. Somehow I missed that her sending me away and not wanting me was actually on her and her inability to care for me. Although rational to the mind, my heart instead held onto my agreement to seeing myself as unwanted, undeserving, and a quitter.

When my marriage fell apart at thirty-three, I was overwhelmed by worthlessness and guilt, emotions that were magnified by fears and shame of being unwanted and a quitter, amplified by the cold-blooded rage of the eleven-year-old inside who had been molested. I had never felt so imprisoned. My cage was small and cramped, like a kennel. It had so many bars it was pitch dark. It was subzero cold, turning my veins into ice. And it pressed in on me like a vise cranking tighter and tighter as I sunk into deeper and deeper despair. It was crushing my life force, emotionally, spiritually, mentally, and physically. Until I gave voice to my feelings; until I engaged my inner eye; until I saw the cage for what it really was: Rich infor mation about the life I wanted and the freedom that was available.

When you turn your inner eye to what you feel, to what you’ve silently agreed to, and to what traps you, you see the transformative truth that animates Hero Living: I am not my cage and I am not my suffering. I want you to really take this in, really internalize it: I am not my cage and I am not my suffering.You are more than your suffering simply because you want more.You are hardwired with the freedom to choose your perception, to choose your own way.You have your feelings to guide you and your inner eye to tell you essential truths.You can unmake the silent agreements that imprison you and make new conscious agreements that liberate you.You can throw the lock and open your life.You are not your cage.You are not your suffering.You are a hero.

For me, this has always been my way out of stagnancy and paralysis. When I find myself trapped in a cage of fear and pain, when I find myself looping with negative thought and cruel self observations, when I retreat from the world and isolate behind the bars of my silent agreements, I engage my inner eye and return to the prompts above. Then I am able to see the cage for what really it is: Information. The cage is rich, insightful information about what I don’t want and thus, rich, insightful information about what I do want. The cage is the loud quiet call to more of myself, to more life. The cage is no cage at all. Can you feel that?

I mentioned the phrase “existential crisis” earlier in this chapter. It describes those moments when our life feels lost; our obstacles feel insurmountable; our day-to-day responsibilities feel pointless; and the meaning of our life feels purposeless. By definition, the word “existential” refers to one’s experience. The word “crisis” comes from the root that means to “sift out.” So an existential crisis is, in fact, an opportunity to sift out that which no longer serves your experience, your life, and your dreams. It dismantles and dissolves your cage and, in the process, frees you up to receive the support you need. It hurts like hell, that’s for sure. But it’s worth it. Trust me, hero, it’s worth it. If you doubt, note your doubt and keep breathing. Just stay with me. If I can do this, so can you.

Ultimately, wherever you’re at in this stride that I call stagnancy and paralysis, whether you’re living with a steady anxiety and fear, or whether you’re threatened and caged from all sides, I end this chapter with its thesis: Breathe and go looking for your truths, hero. Do only this and you have already taken a huge courageous leap into your moment of movement.You have already become the change you wish to be.