The Army Air Arm developed its first crude electric heated flight suit in 1918. Some further development work was conducted in the 1920s, but no serious attention was given the subject until 1940, though the unsatisfactory C-1 electric heated flying suit was standardised in 1938. The increased pace of long-range, high-altitude bomber development was responsible for the renewed interest. The programme faced a number of difficulties including inadequate materials, particularly wiring; unreliable temperature controls; and insufficient aircraft power output. Another problem was that damaged wires had caused injuries to the wearer in earlier suits. Opponents argued that in the event of a suit malfunction, aircraft electrical failure, or bailout, the airman would lack sufficient protection from the cold—a justifiable concern. Within some units in 1943, up to 75% of the frostbite cases were caused by electric garments failures.

Regardless of these concerns, the General Electric Co. developed suits for service testing in mid-1940. These were standardised on 4 April 1941 as the E-1 and F-1 electric heated flying suits. It was not until June, however, that modification orders were issued to install power outlets in bombers, both operational and in production. These were one-piece coverall-type garments worn under standard two-piece winter flying suits to protect aviators from the extreme cold at high altitudes. Electric heated gloves and shoes (described below) were components of these suits. Both suits were identical except for two aspects, the E-1 was used in aircraft with a 12-volt battery system (B-24, B-25, B-26) and was light grey (‘Bunny Rabbit’ suit). The F-1 was used with the B-17’s 24-volt system and was light blue (‘Blue Bunny’). The front was closed by a neck-to-crotch zipper and crotch-to-ankle zippers on both legs. A small zippered opening was located to the right of the crotch for natural relief; former airmen have stated that this was simply accomplished without opening the zipper due to the extreme cold—and no, there was no danger of electrocution! Electrical heating wires were sewn into the suit’s wool fabric, basically the same as a commercial electric blanket. The electrical cord junction box, fitted with an ambient control switch, was on the right waist with a 2 ft. power cord (later suits had this same cord); all suit types were also supplied with a 6 ft. extension cord. Electrical connectors for the heated gloves and shoes were fitted above the wrists and ankles. Black knitted wool wristlets and anklets were fitted, as well as a similar collar. The wiring used could not withstand repeated flexings, and considerable trouble with breakages was experienced. They were wired in series, and a single break would cause the entire suit, gloves, and shoes to cease functioning.

An unrestricted view of the winter AN-J-4 jacket and AN-T-35 trousers with an A-11 intermediate helmet, A-8 goggles, A-10R oxygen mask, A-11 winter gloves, and A-6 winter shoes.

The number of suits that a given aircraft’s power system could support dictated how many the crew could use. In B-17s the priority went to tail and ball turret gunners due to their static, cramped duties; if the aircraft’s generators could produce ample power, the waist gunners would also wear the suits. In B-24s they were worn by the waist and tail gunners. Some airmen wore the electric suit over several sets of long underwear, or a wool uniform and underwear rather than the prescribed single set of long underwear. This much extra clothing served in practice to insulate the wearer from the suit’s heat resulting in cold injuries. The need to wear the suit over only underwear caused another problem, however: if an airman was downed over enemy territory, he did not have suitable clothing for evasion, or more realistically, in which to spend the duration in a Stalag Luft. There were also sizing problems with the E-1 and F-1 suits, and this, coupled with the bulky shearling suits, made movement even more awkward.

Development of improved suits continued into 1943. Suitable wire, able to withstand better than 250,000 flexings, was not developed until May 1943. The new suit was designed in conjunction with the alpaca B-10/A-9 suit, which could be worn over the electric suit as could shearling suits; or it could be worn under light flying suits. The 24 volt F-2 electric heated flying suit was standardised on 13 August 1943. It was a four-piece ensemble comprising electric heated jacket and trousers inserts and unheated outer jacket and trousers. The inserts were made of light OD wool blanket material incorporating more flexible wiring and wired in parallel, eliminating the failure problem with breakages. Electrical controls and fittings were similarly placed as on the E-1 and F-1 suits. Without current the suit was comfortable down to 32°F, and with current, down to –30°F. It was better fitting and allowed greater freedom of movement than earlier suits. The wool-lined dark OD gabardine outer jacket and trousers, with suspenders, were of a simple design with a zippered front and flapped chest pockets; there were no leg pockets or leg seam zippers. An electric connection was fitted in the right chest pocket to plug in a B-8 goggle or oxygen mask heater. Some had a shearling-lined collar. It was designed to be worn over long underwear, wool service shirt and trousers. For additional protection, a light flying suit could be worn over the outer suit. It was made substitute standard on 19 February 1944 when the F-2A electric heated flying suit was standardised with thermostats to control the heat.

This B-17 bombardier wears the down-filled winter B-9 jacket and A-8 trousers. This light OD suit’s hood is trimmed with brown mouton. He also wears A-12 arctic gloves and A-6A winter shoes. He carries a light OD duck E-1 bombardier’s information file containing computers, watches, bombing tables, plotting devices, penlight, pencils, etc. Similar brown leather satchels were also used for mission orders, maps, weather data, and signal instructions.

In the winter of 1942/43 there was a shortage of electric suits in England. An investigation showed that large numbers of E-1 and F-1 suits had been purchased, but most were still stored in stateside depots; issue was pushed and procurement of the F-2 rushed. To make up shortages, British electric gloves and boots were modified to allow their use in US aircraft1. Though an improvement, the F-2 suit was far from ideal, still not providing the needed freedom of movement.

Development of the F-3 electric heated flying suit began in late 1943 and was standardised on 19 February 1944. This well-designed suit was a two-piece style consisting of a dark OD cotton and rayon twill jacket and bib type trousers. It was designed specifically to be worn over long underwear, wool service shirt and trousers, and under the A-15/B-11 suit. As such, the ensemble provided complete comfort at –60°F, though even a light flying suit could be worn over it in ‘milder’ climates. In the event of suit or power failure or bail-out, the combination provided sufficient protection for a considerable time, and also allowed for suitable clothing for ground wear. The waist-length jacket was a collarless design with elastic cuffs and closed by a zipper. An auxiliary power connector was fitted on the left chest for connecting heated goggles, and a ‘pigtail’ connected the jacket and trousers circuits. The trousers had a high bib front, covering the chest, and fabric suspenders. Double-acting, full-length zippers were fitted to the outer seams. Electrical controls and fittings were greatly improved, as was the parallel wiring system, which permitted half the heat to still be supplied if one of the two circuits failed. Snap fasteners connected the gloves and boots to the power circuit. The outfit was better fitting and accommodated more individual size variations by mixing the two pieces. The F-3 was made limited standard on 21 October 1944 when replaced by the F-3A electric heated flying suit. It featured even more improved electrical controls, fittings, and wiring.

Serious research in countering the effects of centrifugal force during high-speed, violent manoeuvres by fighters began in 1942. High G-forces (2–3 Gs were common) during inside loops or pulling out of a dive forces blood toward the lower part of the body; this leaves the brain without sufficient oxygen, resulting in, first grey-out dimmed vision, followed by black-out and unconsciousness. During outside loops or termination of a dive, the opposite occurs and blood rushes to the head resulting in red-out—red vision, eye pain, and a throbbing head. Pilots learned to level off gradually from dives and climbs and would tense their muscles and yell in an attempt to counter the adverse effects, but this had only marginal counter-effects. G-forces also increase fatigue.

Early attempts to develop an anti-G suit were ineffective. Finally, at the end of 1943, a development called the gradient pressure suit (GPS) looked promising. Encased in the suit was a series of interconnected rubber bladders positioned over critical portions of the legs and abdomen; the bladders were automatically inflated when a vacuum instrument pump, integral to the fighter’s air pressure system, sensed 1.5 Gs. An air hose emerged from the suits’ left side to connect with the metering valve to the left of the pilot’s seat.

The GPS type G-1 fighter pilot’s pneumatic suit, developed by the US Navy, was procured in very small numbers. It was a bulky set of two-layered, chest-high overalls made of light OD, inelastic, lieno-weave cloth. It had four bladders over each thigh and calf plus one over the abdomen, this latter held in a separate corset-like belt reinforced with seven steel stays. The 17 bladders were inflated with a complex triple pressure system. The suit’s excessive 10 lb. weight was supported by suspenders. There were zippers on the sides of the abdominal belt and two more running the suit’s length. Adjustments (the suit had to be snug fitting) were accomplished by laces on the legs, thighs, and flanks plus internal leg adjustment straps. The suit was heavy, difficult to don and remove, restrictive, uncomfortable, hot, and complex; it was seen that a change was necessary.

The G-1 was quickly followed by the G-2 fighter pilot’s pneumatic suit using a much simplified single pressure system. It was similar in outward appearance to the G-1, but had long rectangular bladders, one over each calf and thigh, plus the abdominal bladder—a total of only five. The new design also eliminated much of the G-1’s rubber tubing and reduced its weight to 4½ lbs. Standardised on 19 June 1944, they were issued to Eighth and Ninth Air Force fighter units in Europe. However, a still further simplified, cooler, and lighter suit was desired.

The development of the G-2’s replacement began in January 1944. Two types were developed in parallel, using a much simplified bladder system comprising five air cells positioned in the same manner as the G-2’s. The G-3 fighter pilot’s pneumatic suit was actually a skeletonised set of high-waisted ‘trousers’ made of two layers of dark OD nylon; its crotch, hip, and knee areas were cut away. Fitting was accomplished by adjusting a lacing system; once fitted, it was removed and donned using leg-length zippers. Pockets were fitted to both shins. It could be worn under a flying suit and over underwear or over a uniform and under the flying suit; the lacing would have to be readjusted if clothing worn under the suit was changed, due to the need for a very snug fit. There were two variants of the G-3. The 2¼ lb. David Clark Co. G-3 had a single-piece gum rubber bladder system with a rubber tube crossing the small of the back extending 2 ft. from the suit’s side. The 2¾ lb. Berger Brothers Co. G-3 used a vinylite-coated nylon cloth bladder system and had its air tube running across the abdomen. The tube was encased in a nylon sleeve and extended one foot. These early suits were issued as requested by the theatres of operation air forces. The Clark G-3 was standardised on 10 March 1945.

The G-3’s final production version was the G-3A fighter pilot’s pneumatic suit based on the Clark G-3 suit with an improved neoprene bladder system and other minor refinements, though it weighed 3¼ lb. The G-3A was issued to all fighter pilots without special requests being required as with the G-3. It was standardised on 10 March 1945.

This C-54 navigator wears the alpaca-lined intermediate A-15 jacket and B-11 trousers, AN-H-15 summer helmet, A-14 oxygen mask fastened to an H-2 bail-out bottle, A-11 winter gloves, A-6A winter shoes, and AN6512-1 (late B-7) back parachute. He is consulting an E-6A aerial dead reckoning computer.

Another view of the intermediate A-15 jacket and B-11 trousers with A-11 intermediate helmet, A-14 oxygen mask fastened to an H-2 bail-out bottle (its green cable-release is visible), A-11 winter gloves, A-6 winter shoes, and B-4 life vest.

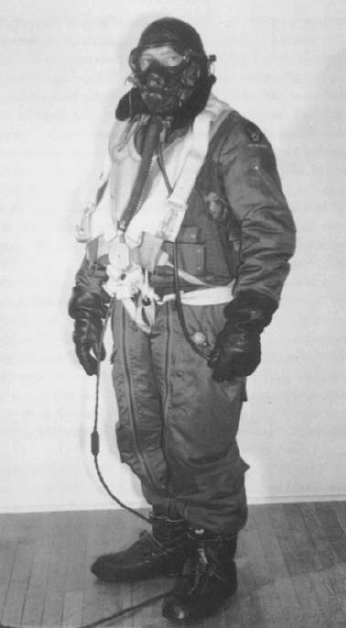

A bomber crewman demonstrates the burden of full equipment: intermediate A-15 jacket and B-11 trousers, A-11 intermediate helmet, A-14 oxygen mask attached to an H-2 bail-out bottle, B-8 goggles, A-11 winter gloves, A-6A winter shoes, C-1 emergency vest (M1911A1 pistol under left arm), B-4 life vest, and A-4 QAC parachute harness (chest pack is detached).

After all the effort to perfect the anti-G suit, they were little use in practice. By the time they were issued in large numbers, their requirement had evaporated as there were virtually no enemy fighters left in the sky, so that there was little need for high G-force generating violent manoeuvres.

Several types of flotation and exposure suits were developed prior to the war; all lacked sufficient protection and were too heavy and bulky. The need for adequate exposure suits was greatly emphasised by the increased flying over the North Atlantic and Aleutian Island areas early in the war. A requirement existed for an exposure suit capable of sustaining life in water temperature of 65° to 35°F.

One of the earlier suits still in use at the outbreak of war was the C-2 flotation suit. It was a one-piece OD coverall with foam flotation pads in the chest and collar. While providing flotation, its use of standard flying helmets, gloves, and shoes did not adequately protect the wearer from cold water. It was standardised on 23 October 1928 and used until declared obsolete on 13 March 1944.

On 29 January 1945 the completely sealed, buoyant R-1 quick-donning anti-exposure flying suit was standardised. This was a one-piece coverall made of orange-yellow two-layer neoprene-coated nylon with integral hood and boots. F-1 exposure gloves were contained in the large, snap-closed, flapped, bellows leg pockets (see Gloves section). The suit was issued in a pull-tab opened, 6×12×12 in. container made of the same material as the suit. One was provided to each crewman/passenger in all bombers and transports flying overwater routes. It was also part of some life-rafts’ component equipment. The suit was large enough to fit all individuals and intended to be donned over standard flying clothes and helmets, necessary for sufficient insulation. It offered protection down to 28 degrees F. Its fullness also provided flotation although it was recommended that the life vest be worn over it.

1 For additional information on RAF flying clothes, see MAA 225, The Royal Air Force 1939–45.