EVERYTHING WAS READY for the 6:30 A.M. departure. The Los Angeles Times had been suspended. The dog was in a kennel. The school, the after-school, the teams, the dance class, the band, the car pool, had all been notified of upcoming absences. Near the front door lay Richard Dyer’s family in luggage form. But Richard himself, sleepless for most of the night, found his early-morning thoughts riffling through what he had packed, like a surgeon suddenly unsure of basic anatomy. Did he own a proper pair of New York shoes anymore? Were Brooks Brothers tassel loafers still the brand of choice? Maybe he should go shopping after they landed, since all his decent clothes were stylish in that questionable California style of casual meets designer meets high school visions of dressing up. Under normal circumstances Richard did not care about such things (he famously wore only one necktie during his Exeter days, a solid brown affair that everyone dubbed the Skidmark. After more than twenty years of living in L.A. he still considered himself a visitor to this world; whatever customs or fashions these natives followed, well, he would participate for the sake of camouflage. So bring on the V-necks, the too-tight T-shirts, the designer jeans, the absurd sunglasses. It was almost fun. Nobody in these climes knew his New York self. Here he was free. Despite this liberation, Richard quietly bore his pedigree like a trench coat in case of rain, his shoulders hunched, ready for an unexpected Northeast chill. This inner Dyerness gave him comfort despite his willful renunciation of the past. Oh, the contradictory nature of self. But soon no more of this secret identity. He was returning to the home planet, with a wife and two kids in tow who were thoroughly Angeleno and potentially mortifying. “Dad, these are my children.” Maybe he should take them shopping as well. Richard tried to picture Emmett and Chloe in the clothes of his youth, Emmett who never met a button he liked, Chloe who insisted on wearing every color of the rainbow, claiming this as her “signature look.” Then there was his wife, Candy, the former meth head who now worked the front desk at a veterinarian’s office, lover of tight pants and turquoise jewelry, whose parents christened her Candy never thinking Candice was within reach, softly snoring by his side, naked and warm and fragrant, her arms and shoulders covered in a tattoo of meandering vines (while Richard had a hand grenade on his chest with the pin pulled). “Dad, this is, this is Candy.” Richard hated his own knee-jerk snobbery. Defend her. “And I love her more than anything!” “And I don’t care what you think!!” “I’m nothing like you!!!” That old familiar feeling took up construction in his stomach, and he thought, I am so fucking doomed.

Jamie Dyer lugged his backpack up three flights of crummy Cobble Hill stairs, the weight more abstract than concrete. He dug out his key. He hated keys. He hated having his own apartment, back in New York no less. It seemed like a defeat. After all the years of traveling, far removed from the mainstream of his roots, filming almost everything the human condition had to offer, Jamie the adventurer, Jamie the fearless documentarian, Jamie the envy of friends who remained stuck in cities and suburbs and careers and families, after all these years, here he was, slouching back to gentrified Brooklyn, like he was fresh from college. His apartment was a mess. He was seven weeks into an I’m-not-cleaning-a-fucking-thing binge and almost expected a homeless man to have been spawned. Welcome home, asshole. Jamie unzipped his backpack, retrieved the HDCAM SR tape with the solemnity of a stolen artifact. He placed it on the table. She was once so beautiful, he thought. Time stood still in her shadow. Jamie, exhausted, stripped down and headed toward bed. Back then sex had been unspeakably fun, the vigorous sweat, the silly sounds, the straight-up thrill of it. Her pussy—Jamie wondered if this was being disrespectful to the dead or if the dead begged for these memories—but her pussy was perfect, with its mitten of dark blond, its interior the impossible smooth of a conch—this was disrespectful, Jamie decided, picturing her spread on his bed instead of the books and magazines and random scraps of paper that surrounded him like a cat lady’s cats. This was no way to live as an adult, but he was five days from reaching terminal disgust. Back to Sylvia. Sexy Sylph. Her breasts conveyed the incredible physics of being both heavy and light, the nipples small and specific, as if added later by a famed enamelist in France. Stop, Jamie thought. But memory pressed on. Her face, her lips, her tongue licking the tip of his cock, her hair swaying against rare, sun-deprived skin. All of this happened almost thirty years ago yet the sensation curled through him, and as Jamie worked the static darkness, he sensed something else on the other side, something else microscopic yet in this grubby atmosphere a thousand times its normal size, scrabbling along the walls and the floor, carrying its weight on eight bent legs, pointy and black, like nibs leaving behind terrible hieroglyphics. Scratch-scratch-scratch.

LAX appeared in the distance, and Richard was relieved. The traffic had been light and they were early, as predicted by Emmett, who had begged for another hour of sleep. “Great, two hours of lurking in the airport,” he muttered from the backseat, his thumbs working a text. God knows what he was typing: my dad sux. Richard periodically checked on him in the rearview mirror, just to confirm he was still there. It was almost disconcerting how handsome and physically mature the boy had become. It seemed in violation of time. Six foot one and in need of a shave. Broad-shouldered with a narrow waist. A natural swimmer. And smart too, gifted in math and science. But whenever Emmett acted his age, which was often, Richard forgot that he came to this obnoxiousness naturally and wasn’t impersonating a pain-in-the-ass kid. The car approached the Delta terminal. Chloe dug into her handbag and asked if she needed her passport. Passports were the new craze at school, all the seventh-grade girls carrying them as if prepared for a sudden whisking to St. Moritz. Chloe had begged and begged for one even though they had never cleared North America, but over Christmas they relented and she spent an entire morning styling herself for her big photo shoot. You would have thought she was a citizen of Fauve. Already the magic of girlhood was being mediated through the complications of becoming a woman, a far less knowable state for Richard. In the car Emmett fake-laughed and poor Chloe bit down on the hook and asked, “What’s so funny?” Emmett wiped his nose along the inner handkerchief of his wrist (the boy generated copious amounts of snot, which always made Richard worry about his possible blast count). “I can’t wait until you’re like nineteen,” he said, “and you’re like traveling to Estonia and some border guard checks your passport. You’ll be so embarrassed your face will crawl under the nearest rock.” Chloe gave a whiny rebuttal and Richard warned Emmett but Emmett was unapologetic. “I’m not allowed to get a small tattoo of a Chinese character representing strength and courage because I’m still too young, and hey, no big deal, I get that, I can wait until I’m eighteen, but Chloe here can dress up like a drag queen named Skittles for her passport photo?” Richard warned Emmett again as he searched for a place on the curb, but Emmett pressed further. “And I’m just saying that when she’s older she’s going to feel really really stupid.” Richard had to double park. “What’s that line from Ampersand, Dad?”—Richard hated the way Emmett said Dad nowadays—“Give it time and shame eventually clambers back as pride. So maybe when Chloe’s thirty she’ll laugh but—” Richard spun around and punched the back of his seat. “Shut the fuck up, please!” he nearly screamed. It was one of his zero-to-ninety outbursts. Instantly Chloe began to cry and Emmett sniffed as if ripping up a disputed contract, after which he opened the door and started unloading the bags with helpful spite. Candy smiled at Richard. “A good start to the trip,” she said. But she knew his battles, knew how fraught both sides of fatherhood could be, and for the most part her sympathy outweighed any frustration. “Take your time with the car,” she told him, squeezing his knee. Richard circled back toward long-term parking. As he drove he imagined heads exploding, which for some reason relaxed him while also confirming his general fuckedupness. The car went into the lot. Before leaving he gave the inside a quick look-over: there on the backseat near the crap-collecting seam was Emmett’s cellphone. The kid must be freaking, probably too prideful to say a word. Maybe its recovery would spur amends. Hey man, you missing this? Oh, and I’m sorry. I’m kind of, well, anxious about going back to New York. Then, amid this fantasy, Richard thought, When had Emmett read Ampersand?

Jamie went up to the fifth floor of the Brill Building, to the offices of RazorRam and his old pal Ram Barrett. Ram had been a star at the Yale School of Drama, a promising actor and director and halfway-decent playwright, but somewhere in his jobless twenties he drifted into editing, specifically reality TV editing, and while he rode that boom into a very nice living, the career had taken its toll. Ram greeted Jamie awkwardly, as if five minutes earlier he had kissed Jamie’s girlfriend or had changed alliances. “What brings you here, not that I don’t love seeing you, I do, of course, I’m just, I thought you were eating peyote in Afghanistan, not to say you’re not doing important work, unlike me, God knows, but I have a family, and bills, and do they even have peyote in Afghanistan?” Ram seemed to plead for a cutaway from his face. “I need a favor,” Jamie said. He stacked the original mini-HD tape and the HDCAM SR tape on Ram’s desk. “I need you to cut these two together. This the beginning, this the end. Clean up the transitions however you think best, do whatever you think best, and then burn me a master. It’s maybe ten, twelve minutes of footage, all pretty self-evident, I think. I’d do the job myself but I’m too close to the subject matter. I need an objective eye, that Ram Barrett touch. And this tape here.” Jamie picked up the HDCAM SR tape. “I have no idea how it looks. The quality might be crap. It also might be, I don’t know, it might be kind of disturbing.” Ram perked up. “Coming from you that means something,” he said. “Do we have a title?” Jamie told him 12:01 P.M. and Ram wrote it down on a Post-it which he headstoned to one of the tapes. “I’ll get to it when I can,” Ram said. “I mean sooner than that, not like I’m some big shot or anything, but I am busy, yeah, with the latest episode of Wall Street/Main Street, but hey, busy is busy. I’ll try to take a look this afternoon.” Jamie said thanks. Back in the elevator he checked his watch and though it was only mid-morning he wondered if he’d ever have a decent answer to that question.

Richard headed toward their meeting spot, one of those awful airport restaurants that reeked of disinfectant, as if Mr. Clean were decomposing in the corner. He passed people milling about the shops and food courts, a parallel world of in-betweenness that was both drab and exotic, the word terminal suggesting possible engine failure, of these people being the last people you would ever see. But Richard was mostly thrilled by the moving sidewalks. It was like the future promised in his youth. A brief vibration grabbed his thigh. Emmett’s phone had a text—

—from someone named T-Bone. Richard tried to decipher the acronym but had no clue except that ;^@ seemed up to no good, and then Carson buzzed in—

—and before Richard could digest its algebra, Kelly checked in—

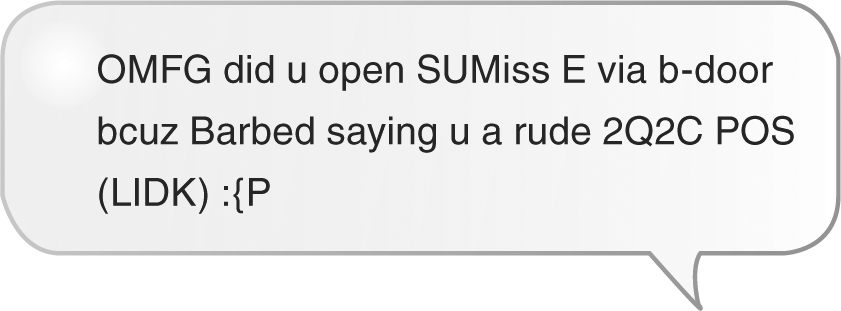

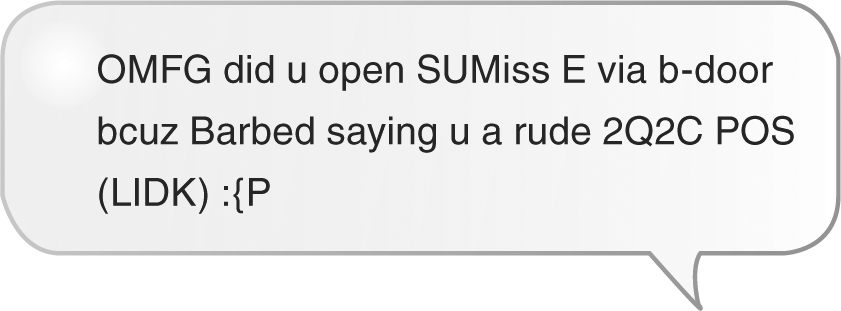

—but what the hell was b-door and 2Q2C and just when Richard was ready to stop a random teenager and ask his advice, Penny cleared things up—

—kind of. Richard read the text twice. Was this Emma, sweet Emma from school, with the brown eyes and the long brown hair? Richard was just wrapping his head around this information when he arrived at the restaurant. He slipped the phone back into his pocket and found his family sitting in a booth, minus Emmett, who was hanging by the gate. Richard went to find him so he could get rid of this damn phone now vibrating nonstop as more and more of Emmett’s friends were waking up and exercising their thumbs. Zzzzzz. Zzzzzz. Zzzzzz. God knows the messages now. What had Emmett done to Emma exactly, cute Emma with all her shades of brown, a friend of Emmett’s since forever. Zzzzzz. Zzzzzz. Richard was ready to hand over the phone without ceremony or teasing, without any paternal condescension whatsoever (every Zzzzzz was like a poke at Emma), but then he spotted Emmett sprawled across two chairs reading Ampersand, no doubt in anticipation of meeting the author. And that was fine. That made sense. Of course he’d be curious. There was no need for permission to be granted. But Richard stopped short, and Emmett looked up and seemed to measure the distance between them as if space and time were defined exclusively by confrontation. Or was Richard putting across this view, remembering his own teenage years? Regardless, a father’s memory is longer. A few feet is merely a continuation of all those previous steps from infancy to—Richard’s pocket gave another nudge. Just give him the fucking phone, he thought, and walk away. He must be missing it. “What?” Emmett finally said full of accusation, and Richard answered with “Nothing,” thrusting his hands into his pockets and turning back toward the restaurant.

After the Brill Building, Jamie called Alice because Alice lived nearby, in Hell’s Kitchen, or what was once Hell’s Kitchen, and Alice was his girlfriend, or almost girlfriend, a girl he saw on occasion, an actress you might recognize from a Xerox commercial (“So real it’s almost … real?”) and a short-lived Apple iMac campaign (she played Eve) but mostly you would know her if you ate at Orso on West 46th Street since Alice had been on the waitstaff there for eighteen years and was well known to its regulars, her presence representing a sort of Kuleshov effect, whether a barometer of consistency in New York—Alice at Orso—or an uncomfortable reminder of dreams gone stagnant—Alice at Orso—or the flat progress of other people’s timelines—Alice at Orso—or the disappearance of once-lovely youth—Alice at Orso—and if you mention Alice at Orso to certain people, first they smile—she’s the best—then they grin—she’s been there forever—then they just grow quiet. We all know Alice. It was early afternoon when Jamie stopped by for a cup of Sanka. This was their code for sex. Sometimes it was Folger’s, sometimes it was Maxwell House. Once he made her laugh by asking if she cared for a Brim job, her laugh sustaining him for the rest of the day. He was saving Chock full o’Nuts for a special occasion. Alice wanted more than just casual coffee—Jamie knew that—but Alice had forgotten how to ask for more and nowadays just took what she could get without much complaint. She was a forty-three-year-old waitress/actress who tried her best. As they drank their coffee, across town Ram Barrett grew more curious about what his old friend had brought him, so he put aside his work and watched this pretty woman answer “How are you?” over and over as if Ram had asked the question, which seemed almost cruel when gauged against her obvious decline, and Ram’s stomach, or not quite his stomach but the area within his belly where that weepy boy took cover, tightened as the question gave its final answer with a funeral and a husband and daughters and a coffin going into the ground, the time code confirming the silence of 12:01 P.M. Then Ram put in the other tape. It took a moment to understand what he was seeing in that tidal light, the stillness of the face and its terrible but affecting reality, as the darkness rose and fell like waves and this woman was made of sand. Jesus. It was hard to watch. But it also inspired Ram, like he was in college again, and he went about assembling the footage long into the evening, tweaking the visuals to enhance the oblique liquid movement, putting in a haunting temporary score (My Neighborhood by Goldmund) and trying to give every cut and transition a particular tone. No doubt about it, the man had talent. As he worked he thought about his younger sister, who had died ten years ago, and when he was finished he emailed the short video to his older sister—Just wanted you to see this—who after crying for an hour forwarded it to her best friend—Warning, the ending is rough but ain’t that the truth.

Richard and family were thirty thousand feet in the air, three hours into a five-hour flight. Candy and Chloe were watching a romantic comedy about time travel, one of those eve-of-marriage plots where the bridegroom-to-be gets confronted by his older divorced self. They were enjoying the movie, the two of them laughing—too loudly, thought Richard, who was busy pushing aside notions of impending death, convinced the plane was going down—now—now—now—and wondering if he had the wherewithal to say the things he should say, like “I love you” to his family, rather than scream or shit his pants or reach over and give Candy’s boobs a quick squeeze. That was still his go-to impulse when presented with the concept of disaster: find nearest girl, squeeze boob. When do those stupid urges go away? Adolescence seems to open a small hole in which the rest of our lives drain. Emmett was sitting in the seat in front of him, and occasionally Richard pretended to search through his carry-on so he could peek through the gap at his 2Q2C POS son. He was a third of the way through Ampersand, roughly the section where Stimpson, Harfield, Matthews, and Rogin begin to plot their senior prank. Should they steal the license plates from the faculty cars, dress the statue of John James Shearing in a nurse’s uniform, remove the clapper from the church bell, all pranks committed by previous classes? Then Edgar Mead, lowly but accepted junior, gives them an idea:

“I told them they should kidnap the headmaster’s son.” Of course it was a joke, one of those things you say thinking you’ve said nothing at all, but when a silence follows you realize, good or bad, you’ve said something. In my defense I was still recovering from my spring vacation with the Vecks, still roiled that my own family had neither the money nor the will to bring me back to San Francisco, still offended that some kids hit the slopes in Vermont and some kids hit the beaches in Florida and all I hit were the books with Mr. Veck, who tutored me so I might limp through junior year without flunking. “The man is doing you a tremendous favor,” my father said via letter. All these favors and opportunities from the Vecks, the stories from Mr. about how my father had saved his life in the war, the half-mast glances from Mrs. like she wished a white cross stood instead of this windbag here. You would have thought the Battle of the Bulge was last week. And then there was Jr. Two weeks of a muddy New England March with Timothy Veck. Who was the one doing the favors? Give me Bastogne any day. So I said it again, seconding that silence. “Absolutely kidnap Veck. I bet he would even enjoy it.”

Richard thought about reaching through the seats and tapping Emmett and saying, “Pretty good, huh?” But esteem for his father seemed a zero-sum game. Rather, he leaned back and rehearsed the next twenty-four hours in his head. “Dad, I need Ampersand.” Nobody knew about the quid pro quo proposal from Rainer Krebs and Eric Harke. “You owe me this.” They were simply going to New York so Emmett and Chloe could meet their grandfather. “It could be a real opportunity for me.” Candy could meet her father-in-law. “I’ll make it a good movie, I swear, and we can write it together, if you want.” They could all meet Andy and get to know him, just like his father wanted. “It’s a win-win.” And maybe Richard and his father would reconcile and shake hands and who knows, maybe even hug. “I’m glad I came.” The plane’s engines—was that sound normal? And the flight attendants—did they look nervous? “Give me Ampersand or I swear I’ll fucking kill you.”

So much happens to us without our knowing. People might talk about us, whisper and judge, and those whispers and judgments are forever in our company, a groundless shadow. Let me defend myself, we might plead, if we were aware of the charges, but they only smile at us and we smile right back. Who knows what about whom? And then there’s the undeniable role of coincidence, the thousand chances in a day. Good fortune. Bad fortune. How many times have we almost died without our realizing it? Life, I’m convinced, is filled with far more near misses than we dare to imagine. Late in waking up, missing a train, not answering a phone, going down 79th Street instead of 80th Street—how many of those moments have spared our life? Until, of course, the blade drops, reverse engineered, it can seem. Like that morning when a bus driver in Queens—let’s call him Stan, Stan Mocker—was tiptoeing to the bathroom so as not to wake his wife, which Stan had done numerous times without incident, but today his right foot slammed into the bureau and he viciously stubbed (in hindsight broke) his toe, and because of that and a few other choice bits of happenstance, at 9:12 A.M. on a Friday near the end of March he would be a few seconds slow in noticing the distracted person stepping from the curb and—boom! The sound would travel with terrible speed. All hearts within hearing would hold a beat, all lungs would gasp, as the world briefly constricted around a newborn center, as if a noise could describe the radius of a soul. Then the sirens would come. All because of a toe. There might be no gods but we are still their playthings. So while Jamie was having his kaffeeklatsch in Alice’s apartment, he had no idea that 12:01 P.M. was being uploaded, forwarded, linked, liked, and shared a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand times, until it quickly became one of the top-rated and most-viewed videos on YouTube with user comments like This is devastating and What an amazing woman and @#$% nasty and I’ve never seen anything like this, thank you, thank you, thank you. It crossed generational lines since it combined the sentimental with the macabre, wrapped up in mothers and wives and tied together with cancer and that greatest of universalities, decay. By the time Jamie mustered the strength to return to RazorRam to pick up the edited version, two days and almost two hundred thousand views had passed. Jamie’s brother was arriving later that afternoon, and that, plus the situation with his father and his uncertainty over the video’s extreme postscript, gave Jamie a distracted air, which Ram Barrett read as soon-to-be-unleashed fury. Ram was ready with an explanation and an apology—“I swear I never thought it would go viral”—though mostly he appreciated the exquisite reality of the situation. When Jamie finally broke the silence and said, “I’m not going to watch the thing so just tell me the truth,” Ram searched for the proper angle. “The truth?” “Yeah,” Jamie said. “Like is it a total disaster?” Ram considered this for a moment. “No,” he said, “it’s pretty great.” The things we don’t know until it’s too late.

Coming into LaGuardia, Richard was on the wrong side of the approach. The other windows gathered up the skyline view with its rows of razor-sharp buildings, like a shark bursting through water. Candy strained for a peek, as did Chloe, while Emmett remained stubbornly uninterested. He was nearing the final chapters of Ampersand, his attention periodically flipping to the back of the book and the photo of his grandfather. There was a definite resemblance, Richard thought, returning his seatback to the upright position, a resemblance in those eyes, like odds were being calculated, emotions dictated by a set of knowable rules. The boy was probably destined for a full ride at Stanford or Caltech, robotics one of his interests. The landing gear went down, its thump introducing the possibility of catastrophic failure, but Richard had moved into the acceptance phase of the flight, as if there were a special providence in the fall of a Boeing 737–800, and he almost dared a fireball. The last time he was in New York it was a mecca for a person in his line of abuse. He could give the family a tour of his humble chemical beginnings, sit them in a double-decker bus and start with the Red Dragon on 73rd and Third and the bartender who never carded and knew Richard as Jack-and-Coke, and after that head into Central Park, where pot and speed had their early reign, the dealers singing sense-sense-sensimilla and ice-ice as if a musical number were about to commence, and while in the Upper East Side be sure to peek into the parentless apartments where Whip-its and poppers were the party favors of choice, and definitely go west and pass the natural history museum and mention how a tab of acid could put flesh back onto bone. Funny, he could think back on those days and blush at their innocence. The plane took its final turn, banking over the gray lake of a cemetery. “That’s a lot of dead people,” Candy said, and she gave Richard her hand. She hated the landing part. But Richard’s gloom was lifting, even if he was wary of what hid under the sheet, something he discussed in his last meeting—that excited feeling of return. His chemical tour would continue down in SoHo, where eighteen-year-old Richard discovered his true passion, cocaine in all its forms (imagine Lou Reed covering Lou Rawls’s “You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine”), like in that loft on Wooster where he dabbled with free-base (viva la liberación) and that other loft on Wooster where he pondered speedballs (picture a ménage à trois with Rogers and Astaire) and from there get your camera ready for the ex–ink factory on Grand where he met his number-one-true-love (do you take this rock to be your lawfully wedded wife) and after that stumble into Alphabet City (the ABCs of being fucked) into one of those near-abandoned tenements near Tompkins (no plumbing, no electricity) lit by the flicker of butane (oh, the multilevel thrill) revealing all you can imagine (a full-blown crackhead) and all you can never understand (this is the person I deserve to be). The plane touched down. Candy clapped. Richard always hated the people who clapped.

They sat around a table, ten of them, nineteen, twenty years old, six males, four females, none of them as attractive, as outright irresistible, as the nineteen- and twenty-year-olds of the imagination. Then again, this was the New School. These kids were the hand-me-downs from NYU, their sleeves longer than their reach. They stared at Jamie and propably wondered Who the hell is this guy and what gives him the right to teach our class? I mean, NYU has Errol Morris. And Columbia has Miloš Forman. Jamie Dyer? Ooh, a film course with the Jamie Dyer. Jamie drummed a fuck-you-too rhythm on his chest, a nervous yet enjoyable tic, and in terms of beat and tempo, one in which he excelled. He grinned at the class. Thirty thousand dollars a year for this chest-drumming maestro? Serves them right. They were foolish enough to sign up for something called Dramamentary: A Search for the Real in the Hyperreal. They had lost all credibility at the door. Jamie considered putting in 12:01 P.M. and maybe getting their opinion (he was still unaware of its growing viral status, though his class was aware, was in fact buzzing about its strange effect and were curious who had made the uncredited thing and if it was even genuine), but Jamie wasn’t yet ready to suffer through that memory. Since Sylvia was on his mind, he started to tell them about that time in college (and there was a point, he swore) when he went to Vermont for a ski trip: “I was driving with my high school girlfriend, like my first love, my first everything, and we were at that off-and-on-again stage, both of us at different colleges, but we were going on this ski trip together and I was really excited, not sure how she felt, but I was really excited, and we were driving on one of those almost too-perfect Vermont country roads, near Middlebury—she went to Middlebury College—and there wasn’t a lot of traffic on this road, it was empty, and I remember seeing this dog up ahead, a brown Lab, he was sort of jogging along the side of the road, and I remember thinking, Watch out for that dog, you know, in case it makes a sudden turn, and my girlfriend, she wasn’t really my girlfriend then, we had basically broken up because of the distance thing, anyway, she pointed at the dog because she was probably thinking the same thing, when from the other side of the road another dog bursts through the bushes and shoots out right in front of the car, like it was playing a game of how-close. Well, too close. I swear every tire rolled over him. It was the sickest feeling I had ever felt. I remember thinking, Oh no, oh no, God no. Did that really just happen? That moment of instant change. My girlfriend took such a deep breath that it was like she stole the air from my lungs. We stopped the car, quickly got out. The dog, it was some kind of collie mix, it wasn’t dead but you knew it was not long for this world. All crumpled up. Blood was coming out of its mouth. All I could say was, Oh no. The dog tried to get up, but its spine must have been broken. But damn if it didn’t try, again and again. Just terrible. By now the other dog, the brown Lab, he stopped and watched us from a distance. It must’ve been its friend, not to anthropomorphize. At one point it sat down. I tried to touch the dog, the dog I had hit, but it bit at my hand, like I was planning on hurting it more. That was hard. I didn’t know what to do. This is before cellphones, mind you. I wanted to find the owner, obviously. So I tell my girlfriend, not really my girlfriend, to stay with the dog while I start running from house to house, but the houses around here aren’t very close together and I’m running and I’m getting winded and I’m not in the best of shape and either nobody’s home or they don’t have a dog or their dog is by their side, it’s all no luck until I get to a house and it’s a nice house, like a gentleman’s farm, and this woman answers, middle-aged but hell, I’m probably her age now, and I ask her if she has a collie-like dog, and she says yes, and I tell her that I think I just hit it with my car, that I hit it badly, that I don’t think it’s going to live. Now she’s pretty cool and collected, calm and collected, even-keeled, whatever, maybe she’s just reacting to my obvious panic, but, she gets her husband, they seem to be Boston transplants with some money, and the two of them jump into their car, a Range Rover, with me in the backseat, and it’s like they’re my parents and I’ve done something very, very bad. We drive about two miles, I can’t believe I ran that far, and we get to where my car’s pulled over and where my no-longer-girlfriend-but-the-woman-I-still-totally-love is sitting with the dog, trying to comfort it, her jacket covering its body, keeping it warm. The second the couple sees the situation, they know it’s hopeless. But the dog is definitely still alive. And the woman, it must’ve been her dog, and maybe the brown Lab was his dog, maybe this is their second marriage, their Vermont reinvention, anyway, the brown Lab goes over to the man’s side, and the woman runs to the injured dog but at the five-foot mark she stops, because it is undeniably grim, and those last few steps she takes real slow, like she’s walking down the aisle or something. By now I’m at the side of my car. I’m almost in tears. My girlfriend leaves the dog, to give this woman some space. I’ve never killed anything before. This woman kneels and puts her hands on the dog like she’s going to heal it, like she still has that fantasy from childhood, that you can magically heal something with your touch, but she can’t, of course, no matter how much she tries, and she buries her face into the fur, and she’s crying, weeping really, keening, and she looks up at the sky and stretches her arms heavenward in that classic pose of why, why, why—I remember thinking, Wow, that’s dramatic—and she lets loose with this cry of pure lament, like it was scraped from the bottom of her soul, so real, you know, and almost beautiful, I thought, like this right here is the meaning of life, right here, and then she um, she um, she howls the dog’s name.” Jamie stopped, no longer sure what the point of the story was. He had lost his way, sidetracked by the unexpected pleasure of its active remembering. At eighteen it was hands down the worst thing he had ever seen, watching this dog suffer, watching this woman wail, watching it all and knowing it was all his fault. Sylvia seemed almost comfortable in the situation, like high emotion was a shared experience, two players or more. And Jamie thought maybe this will bring us back together, maybe this is what we needed. Then the woman cried the dog’s name—“Mr. Bumpus, Mr. Bumpus, Mr. Bumpus!” Mr. Bumpus? Who the hell names their dog Mr. Bumpus? There he was, his whole world thrown open, like he was the key and the dog was the lock and on the other side he glimpsed life, or life as reflected through pain and loss, that must have been the point of the story, but then he heard “Mr. Bumpus” and it slammed the door shut and turned the whole story into a punch line, a goddamn joke. Maybe that was the point. The woman rested her head on Mr. Bumpus’s chest, gathered up the fur around its neck and started to lull, “You’re a good dog, you’re a good dog.” The class waited for Jamie to regain the story’s thread but instead he apologized for this tangent and dove straight ahead into a discussion of their short film projects, which were uniformly awful.

The taxi drove over the Triborough-now-RFK bridge, the sunset an hour behind lower Manhattan, its vestige of light almost ultraviolet. Candy and Chloe and Emmett were in the backseat talking, or Chloe and Candy were talking, but the protective barrier and the Persian music made it impossible for Richard to hear what they were saying. For the first five minutes he kept turning around and asking, “What?” and caught the gist of their excitement—Bergdorf’s and Tiffany’s, Friends and Seinfeld and Sex and the City—but after a while Richard gave up and returned to New York, alone. He was feeling carsick. It might have been the music, with its electric oud and high-pitched singer, like Scheherazade on the dance floor. Or the foul perfume of that bottle stuck to the dash. Maybe it was just coming back that turned his stomach. This particular approach Richard knew well since it was how they drove back from Southampton every weekend, Mom behind the wheel, Dad doing the Sunday crossword, Richard and Jamie in the back playing Twenty Questions. “Is he dead?” “No.” “Is he famous?” “No.” “Do I know him?” “Yes.” “Is he me?” No, Richard told himself, I have a life beyond my old life, the family in the backseat a testament to that fact. At first Richard never wanted children. “I’ll fuck it up,” he told Candy when she told him she was pregnant. “I’ll fuck it up and you’ll hate me for it and that’ll fuck us up and then I’m back to being a fuckup instead of a fuckup who’s trying his best to be less fucked up.” And he was trying his best, albeit unsuccessfully, unlike Candy, who was two years sober and dating him against the advice of everyone. “I have faith in you,” she said in a way that was never annoying, “and I’m feeling all this love and I want to share it with whatever’s brewing inside me.” But Richard didn’t rise to the occasion. Instead, he disappeared. For seven months. But near the end he tried his best again, and he was in the delivery room for the arrival of eight pounds’ worth of shrieking, shaking, light-blue-shading-to-pink boy. “He’s lovely,” one of the nurses told him as she wiped clean the gunky mess. But all Richard could see was a stranger, or worse, an intruder, or even worse, a fellow addict suffering through detox. “A future heartbreaker,” another nurse said. Richard wanted to throttle them. Because his first thought, his forever first thought was, I could so easily pick this thing up and smash it to the floor. The taxi merged onto the FDR Drive, and Manhattan was underfoot again. But feelings for the boy did come, haltingly, every month Emmett carving a slightly bigger space within Richard. It was almost like Richard’s own pregnancy; the extra weight might have gone unnoticed but by the first year it was there, not entirely pleasant, and Richard delivered himself into the world of fathers, powerless but clean. But for the sin of that first thought, Richard had to imagine the boy always hanging on by a thread. The taxi turned onto 96th. “This is my old neighborhood,” Richard told the backseat, and he realized that the whole way in he never once looked for the missing twin towers.

Released from the subway at 77th and Lexington, Jamie headed toward the Carlyle on Madison. It was almost ten o’clock. The weather was chilly, winter still in control of night despite the day’s advances. Jamie wore an inadequate corduroy jacket, but he was meeting his brother at Bemelmans and no matter his low-down fantasies he wanted to look presentable, hence the shave and the shower and the lack of his warmer but grubby Carhartt. He passed Lenox Hill Hospital, people loitering around in a sort of 1970s tableau of New York. He remembered when Richard had done some time here, when he was twenty-two, a fuckup beyond measure, and ended up at the emergency room after a harrowing night, the details of which he never discussed with anyone. “I need to die,” he told the admitting nurse. “I’m trying my best but it’s just not working.” Up to the psych ward he went. Jamie visited a few days later, went through those locked doors on the eighth floor and wondered what he was going to say. People milled about the central common area. It almost seemed as if the visitors were the ones afflicted, as if in here the world was reversed, the sad and suicidal, the psychotic, in total understanding of the truth, that they were lost, while family and friends and lovers tried desperately to find their way home. There was no screaming, no oddball behavior. Voices whispered and hands rummaged for something to do. Jamie saw Richard sitting by himself at a table near the back. He was pale and skinny, dark around the eyes but otherwise intact, like a house gutted by fire. Richard made no sign of noticing Jamie even when Jamie touched the table and said, “I’m glad you’re safe.” There was silence until Richard finally spoke. He spoke slowly and calmly. “I’m not sure I like you,” he said. “I think maybe you’re full of shit. But hey”—Richard lifted his arm to the scene around him—“look at the triumph I’ve made. But for the last six years I’ve pretty much wanted to hit you in the face.” Typical of his brother to lunge rather than embrace. “I don’t know why I don’t let myself like you. Maybe one day I will. Or I hope so.” Jamie nodded, neither shocked nor amused. “I’m just here to show my support,” he said. “To tell you I love you and I’m glad you’re getting help again.” Did he mean this? Did he care? Or was he full of shit? Jamie crossed Park. The last time he saw Richard was two years ago, when he visited L.A. for Christmas. As a gift he drew pencil portraits of Emmett and Chloe, and Candy overreacted to their artistry, though Jamie did put in extra effort, hoping they might get framed and Richard would have to pass them every day. Near Madison “Whole Lotta Love” sounded and Jamie checked the caller ID and its accompanying photo: Sylvia smiling, snapped a few months before she died. Who was this ghost? Jamie stared at those eyes in sad retrograde, and instead of answering and breaking the spell, he allowed himself to be haunted.

Bemelmans was New York in its heyday, whatever heyday you might conjure, say when the city was really fun, yes, back then, when money and smoking and drinking were part of the great grand implied, when men looked great, women looked greater, and everybody was having sex on the sly. All of this happened before our time. Even our parents lamented about what had been lost, as if we all peeked from the banister and watched the grown-ups mingle downstairs. Our someday never quite came. Except at Bemelmans. At Bemelmans the walls were decorated with charming murals by what’s-his-name of Madeline fame, his Central Park inhabited by dapper cats and dapper dogs, which added to its storybook quality, the children’s fantasy of where adults congregate after they kiss you good night. It was a place of mysterious low light and red leather booths and uniformed waiters serving cocktails with names like Whiskey Smash and The Valencia, and a piano player playing “As Time Goes By” every hour for all the new arrivals, like good old Ned Durango who bushwhacked through the crowd and planted his elbow on the bar like Balboa at the Pacific taking possession of all he surveyed.

Unlike Ned Durango in Pink Eye, Richard divided his twelve-dollar Diet Coke into fifty-cent sips and resented every plink of the piano that clogged the middle of the room. His brother, no surprise, was late. Every newcomer carried an expectation of Jamie but the truth was another couple overdressed or underdressed. Irving Berlin turned into Cole Porter. Candy and the children were upstairs in a two-bedroom suite courtesy of his father. A chilled bottle of champagne greeted their arrival—love Dad—which enraged Richard but made Candy laugh. “He’s trying,” she said. Chloe bounced from room to room eager for the morning curtain and its first showing of New York! starring Chloe Dyer. And Emmett? He complained about sharing a bedroom with his sister. “It’s not like we’re ten anymore,” he told Richard, and Richard gave him an anachronistic, out-of-the-blue “Dem’s de breaks, bud.” The stupid things fathers say to their sons. Cole Porter turned into George Gershwin. These songs brought to mind more glamorous people leading more glamorous lives and underscored Bemelmans as a movie set in search of a proper star. This is for you, the piano player lied. Finally the door delivered Jamie—thank God—his eyes blinking as if darkness were the brightest of lights, and Richard practically jumped and waved, Jamie touched by his enthusiasm. The brothers smiled and shook hands as if a net divided them. Despite everything they were the only ones who knew how to play certain games. History receded into a gentler past. Or was it the past that receded into a more gentle history? Either way, they shared that old conspiratorial Dyer air. I watched them from a corner booth, the best in the house. I wish I could claim some Dickensian coincidence in my being here, but that afternoon I had overheard Jamie talking to his father on the phone, mentioning Bemelmans and meeting up with Richard, and I decided to take the opportunity to bump into the brothers. Richard? Jamie? Oh hey, wow, long time, et cetera, et cetera. Quite the gamut of conversation chased its tail in my head. I would run into them with Bea on my arm, Bea who sat next to me in the booth, drinking her Carlyle Punch and looking almost thirty in her hydrangea-blue Anita dress, though the silk choker rendered her neck grade school. No doubt my lawyer would disapprove, and my wife, my children, my dead father, my dead mother. But I didn’t care. I reached under the table, unrestrained by order. If only this was the worst thing I’d ever done. George Gershwin turned into Harold Arlen. Bea perked up. This song she recognized. I readied myself to get up, slightly disappointed that the brothers hadn’t seen me first, and I was almost on my feet when Richard and Jamie started to laugh and shake their heads, and I wondered if maybe they had seen me—Don’t move, Philip Topping at five o’clock!—if maybe I looked like a joke. Was the velvet jacket a mistake? The pocket square? Those brutes. With a certain kind of fury I tossed a hundred-dollar bill on the table and grabbed Bea, who protested, but I prevailed. Near the door the waiter rushed over and stopped me. It seemed I was sixty dollars short.