“A new day has dawned. Civilization will never loose its hold on Shanghai … the gates of Peking will never again be closed against the methods of modern man.”

—SENATOR ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE

ON THE MORNING OF April 1, 1900, six of the Americans to whom civilization was committed lay fogbound on the China Sea. Mrs. Edwin H. Conger, wife of the American minister at Peking, was returning from a visit to the States; with her she brought her daughter Laura and four other ladies whom she wanted to show the wonderful things being done for China.

Naturally the fog was exasperating. The more so since Mrs. Conger—by now rather used to diplomatic prerogatives—could do nothing to hurry along the little Japanese steamer Negato. “I have to watch myself,” she confided to her diary. “The Captain is running this ship and I must hands off.”

Her patience was rewarded. The fog lifted, and on April 3 the Negato dropped anchor off Tientsin. Handkerchiefs fluttered as an official launch bobbed alongside. Aboard was Minister Conger himself—GOP wheelhorse … Civil War veteran … close friend of President McKinley.

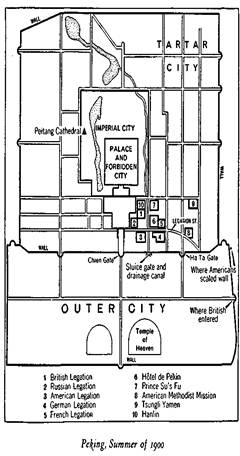

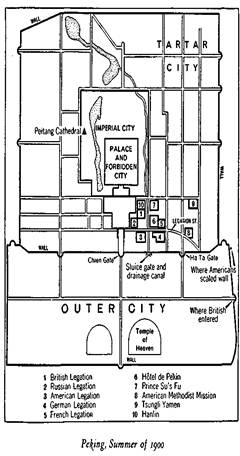

Ashore the ladies were whisked to the legation’s special train, and then ninety miles inland to Machiapu, the rambling station just outside the walls of Peking. A waiting caravan of carts and sedan chairs carried them through the Yungting gate, and now they were in the crowded outer city, with its bustling shops and markets. Continuing on, they passed through another massive wall and into the newer Tartar City. Within its walls and just ahead lay the mysterious Imperial City, and within that the even more mysterious Forbidden City. It was all like a nest of boxes, but the caravan didn’t go any deeper. Just before the Imperial City, it turned into the foreign quarter on Legation Street and drew up at the American compound. Fireworks popped and crackled, celebrating the return of the minister’s lady.

In no time Mrs. Conger was back in the daily routine—picnics … formal calls … stiff dinners at the British Legation, where Queen Victoria’s portrait seemed to chaperon the proceedings. Far gayer were Sir Robert Hart’s lawn parties. The old gentleman was Chief Inspector of the Imperial Chinese Customs; he had been in China forever and by now had accumulated a private brass band. On a more modest scale were Mrs. Conger’s own “Wednesday afternoons,” when the Continental set tried to adjust to homelike Iowa hospitality.

It was a compact little world completely isolated from the Chinese. Concentrated in the small area between the Imperial Palace on the north and the great Tartar Wall on the south, the diplomatic community visited back and forth, strolled Legation Street, shopped at Imbeck’s, and watched each other endlessly. Was Baron de Pokotilov about to wring another concession for his Russo-Chinese Bank? Were the Germans planning to extend their new sphere of influence beyond Shantung Province? Arriving last on the scene, the Americans played a minor role in this political game, but they lived the same way and were equally interested in the latest mysterious visitors stopping at the Hôtel de Pékin.

Completely engrossed in themselves, no one saw much of the Chinese—just the harassed officials of the Tsungli Yamen, as the Imperial Foreign Office was called. Here the diplomats went to complain, or demand some new concession. Beyond that there was little contact. The legation community shared nothing with the rest of teeming, crowded Peking except the heat, the dust, and the endless stray dogs that all seemed to bite.

This April everything was the same as always—only not quite. Visitors to the trading quarter noticed that the price of knives was soaring. Signs appeared in doorways announcing “Swords made here.” People’s gardeners and houseboys began to disappear. Soon the legation colony noted a new rudeness on the streets—often the unmistakable phrase “foreign devil” snarled by some passerby. Around the end of April posters blossomed on the walls, partly religious mumbo-jumbo but partly very clear indeed: “The will of Heaven is that the telegraph wires be first cut, then the railways torn up, and then shall the foreign devils be decapitated.”

The old China hands understood. The native patriotic society colloquially called Boxers—literally “Fists of Righteous Harmony”—was spreading to Peking from the south, preaching its anti-foreign gospel. And it had fertile soil to grow on. Foreign governments had exacted humiliating territorial concessions. Foreign railroads had thrown thousands of boatmen out of work. Foreign missionaries were interfering with local courts when native Christians were involved. The foreigner also proved a convenient scapegoat to blame for flood, famine, and now the drought that parched the country. Nor did it help when a boy arrested for suspicious behavior confessed that he had been paid by foreigners to poison the wells.

It made no difference that the Americans had no sphere of influence, or that the American missionaries were mostly mild men and women innocuously engaged in teaching school. To the Boxers all foreigners were alike; all were to blame for China’s troubles.

And to this the Boxers had an easy answer—kill the foreign devils. For those who feared foreign guns and bullets, they had another answer—the Boxers couldn’t be hit. Wear the Boxers sash, carry the yellow paper talisman, learn the cant, follow the ritual, and the true believer would be protected. High priests of the movement were happy to demonstrate; bravely they faced “firing squads,” and the doubters were quickly convinced … unaware that the shots were blank.

Patriotic Chinese flocked to the Boxer banners, and others not so idealistic joined in the lively hope of plunder. The Chinese imperial government looked on passively, and under the circumstances, this amounted to approval.

Here and there, a few Chinese warned their foreign friends. Around the middle of May Dr. Robert Colter, an American physician in Peking for eighteen years, got the word from a grateful native patient. He passed the news along to the U. S. Legation, but made little impression. Writing the folks at home a few days later, Minister Conger assured them there was no danger. Outside on Legation Street, long carts full of swords and spears began coming in from the outer city.

About the same time, Bishop Favier of the French Cathedral heard from his native converts (“secondary devils”), who were also scheduled for slaughter. On May 19, he urged Minister Pichon to send for troops: “Peking is surrounded on all sides and I beg you will be assured I am well informed.”

Sir Claude MacDonald, the British minister, was told about the bishop’s appeal but he didn’t worry. He had been with the Army in Egypt before turning diplomat, and he knew that these colonial storms blew over. A few blocks away a new Boxer poster proclaimed “An admirable way to destroy foreign buildings.”

On May 24, the legation district suddenly stirred. Sedan chairs hurried through the streets converging on the British compound. It was Queen Victoria’s birthday, and Sir Claude was celebrating with a state dinner. Afterward, by the light of weird colored lanterns the sixty carefully selected guests sipped champagne on the lawn and danced to the music of Sir Robert Hart’s brass band. In the servants’ quarters red and black cards mysteriously appeared, warning that those who waited on the foreign devils were also doomed.

By the end of the month the diplomatic families were starting as usual for their summer homes in the nearby western hills. Among the early arrivals were the wife of the American first secretary, Mrs. Herbert Squiers, her three children, two governesses, and an attractive house guest from home, Polly Condit Smith. They had barely settled on the 28th, when they saw huge clouds of smoke rolling up from the Fengtai railway junction just below.

In Peking a breathless, dusty messenger clattered up Legation Street, shouting that the Boxers were burning Fengtai station and its sheds. Worse still, they were besieging the Belgian engineers and their families at Chang Hsin Tien some sixteen miles away. The ministers frantically compared notes, not knowing what to do.

Others moved faster. M. Auguste Chamot, Swiss proprietor of the Hôtel de Pékin, recruited a rescue team that saved the Belgians. Dr. George Ernest Morrison, resourceful correspondent of the London Times, forgot about his deadline … rushed to the hills where he knew the Squiers family were stranded. An hour later Squiers himself borrowed a Cossack from the Russian Legation and dashed off to join them. The little group huddled all night in the flickering light of the Fengtai flames, then slipped back to Peking in the morning.

But it was no longer safe anywhere. In Peking itself, the Boxers were now burning the little trolleys that creaked along the foot of the outer wall. Again Dr. Morrison set out for the scene. He was an incurable wanderer—once he was even court physician to the Sultan of Wazar—but he had never seen anything like this. A howling mob tried to tear him apart. He turned and ran back to the Legation District.

Fortunately, help was coming. The ministers had finally demanded more guards, and the relief train arrived from Tientsin in the last fading daylight of May 31. It unloaded detachments of American, British, Russian, French, Italian, and Japanese marines—340 men altogether. (Some Germans and Austrians would come later.) They had been scraped together on the spur of the moment—so hastily that the Americans came in winter uniform and the Russians forgot their cannon. But they were there. And as they marched toward the Legation District, the Chinese mobs fell back silent. The British consular students knew it was just what the beggars needed; they rushed to greet their men, singing “Soldiers of the Queen.”

That was all it took. In a day or so life was normal again. At the Peking Club, the members once more sipped their ices, or complained about Count von Soden, the young German military attaché who played vile tennis and worse billiards.

While Peking relaxed, the provinces blazed in violence. At Yungching two young English missionaries, Harry Norman and Charles Robinson, were seized and beheaded on June 1. At Paoting-fu, thirty-two more missionaries were trapped. The Reverend Horace Tracy Pitkin—a stern, lantern-jawed man of God from Philadelphia—sold his life dearly, firing at the Boxers until his ammunition ran out. More often the doomed missionaries were gentle to the end. “Thank heaven we drove them off without killing any,” was one of the last entries in the Reverend Herbert Dixon’s diary. When Mrs. Arnold Lovitt of the American Baptist Mission was seized at Taiyuan-fu, she told her captor, “We have done you no harm, but only sought you good, why do you treat us so?” The Boxer carefully removed her glasses before beheading her.

Minister Conger seemed paralyzed. When asked for a military escort to help rescue the American Board Mission at nearby Tungchow, he regretfully explained that he must not risk his marines. The Reverend W. S. Ament sighed, went to Tungchow alone and saved the people himself. In their exasperation, the American missionaries cabled President McKinley direct on June 8. It was a courteous message, appealing for help and pointing out that the Chinese government’s policy was “double-faced.”

Would the Imperial Telegraph Service forward such an outspoken message? Certainly. Only one change was required: the hyphen must be erased and “double faced” charged as two words.

In a way the incident symbolized the whole struggle. The simple gullibility of the West; the polite, impenetrable ambiguity of Peking officialdom. To the foreigners, this sort of behavior was one more example of Chinese hypocrisy. Actually it was often indecision. The aged, rouge-smeared Empress Dowager sat isolated in her pink palace, pulled this way and that. The court intrigue was incredibly complex—there was even a false eunuch. The vain old woman was generally influenced by the last person who saw her, and Prince Tuan—father of the heir apparent and foe of everything foreign—usually managed to be that. But not always. Sometimes it was pleasant Prince Ching, who thought railways might even help China; sometimes it was crusty General Jung Lu, who knew what a Krupp gun could do. It was all so difficult for an ex-Iowa congressman to fathom.

Then on June 9 the drift became crystal clear. The Boxers burned the grandstand at the race course—the foreign colony’s own center of social intrigue. Four young British consular students could hardly believe such villainy was possible. Riding out to investigate, they were mobbed by swarms of Boxers chanting, “Kill! Kill! Kill!” They barely made it back to safety.

Chinese government troops watched with interest from the walls. They took no active part, but their banners bore the legend “Exterminate the foreigner.” Rumor spread that soldiers and Boxers together would turn on the legations that night. Nothing happened, but Sir Claude MacDonald had now seen enough. He wired Tientsin for heavy reinforcements. The reply was encouraging—Admiral Seymour would leave at once with nine hundred men.

All next day the legations waited. No one knew that the railway was destroyed. Nor could anyone check; the wires were now out. On June 11 the Japanese Chancellor Sugiyama set out for the station, hoping to pick up some news. He had just passed Yungting gate when some Chinese soldiers appeared, yanked him from his cart, and hacked him to pieces.

Back at the American Legation Minister Conger sat at his roll-top desk, pondering what to do. In the drawing room—a wonderful hodgepodge of Ming vases, Morris chairs and calendars pasted on lacquered walls—Mrs. Conger filled in her diary: “If men think he should do more for them and say unkind things, he does not let it hurt him, and replies kindly but firmly.”

Baron von Ketteler, the German minister, believed in action. Years before, when he was military attaché, his blue eyes and handsome mustache made him quite the most dashing blade in Peking. Since then he had served in Washington, married an American heiress, and generally settled down. But he still had a low boiling point, and he reached it on the morning of June 13. Down Legation Street, before his very eyes, came a pony cart carrying a Boxer in full regalia—ribbons, white tunic, red sash, everything. None had ventured so close before, and this man was even sharpening his sword on his boots. The baron personally yanked him off the cart and thrashed him with the heavy cane he liked to carry.

The example was ignored. That afternoon bands of Boxers broke into the outer city and began burning churches. The diplomats did nothing, but once again the Swiss hotelkeeper Auguste Chamot rose to the occasion. He and his young American wife (a McCarthy from San Francisco) rushed to the blazing South Cathedral, brought back a padre and twenty-five nuns.

The fires continued: Asbury Church … the blind asylum … Sir Robert Hart’s customs buildings. When Watson’s drugstore went up on the 16th, explosive chemicals sprayed flames all over the trading quarter. Soon they spread to the huge pagoda atop the Chien gate, a famous Peking landmark. The foreign colony gasped to think that a people could do such a thing to their own most cherished possessions. In the Imperial City the Empress Dowager watched grimly from a little hill to the west of the Southern Lake.

The crisis came June 19. That afternoon the Tsungli Yamen delivered eleven red envelopes to the eleven legations. Inside each a polite letter on ruled rice paper explained that relations were broken; the ministers and their staffs must leave within twenty-four hours—specifically, by 4:00 P.M. the following day.

Minister Conger rushed from the American compound, joined his colleagues at the Spanish Legation. Here they sat around, excitedly arguing what to do. To leave would be perilous; to stay would violate all protocol. Finally, it was decided to leave, but to ask for more time. To work out the details, they urged the Yamen to receive them at 9:00 A.M. next morning.

News always spread fast in Peking, but never faster than now. At the American Legation, Polly Condit Smith debated how to fill the single small bag she would be allowed to take—a warm coat or six fresh blouses?

At the American Methodist compound a mile to the east, the missionaries faced a far grimmer problem. Some seven hundred native Christians had come to the place for protection. Evacuation would mean leaving them behind—to certain death. Nor would it help for the missionaries to stay with them; that would draw the Boxers’ attention all the more quickly.

In the small hours of the night the missionary leaders penned a desperate plea to Minister Conger: “For the sake of these, your fellow Christians, we ask you to delay your departure by every pretext possible. … We appeal to you in the name of Humanity and Christianity not to abandon them. …”

Conger was unimpressed. The Legation staff began rounding up ponies and carts for the flight. The missionaries assembled their frightened Chinese schoolgirls … broke the news … gave them money and told them to scatter when the time came to leave. It was as difficult to say as it must have been for the girls to understand. Men like the Reverend Frank Gamewell had devoted their lives to spreading the ideals of Christ. No matter how hard they tried to justify their departure, they couldn’t help wondering whether this was really the Christian thing to do.

On the morning of June 20 the ministers reassembled at 9:00 but the Yamen hadn’t answered their request for an audience. The consensus was to wait a little longer. Baron von Ketteler announced he would go anyhow. They said it was dangerous. He replied nothing would happen; he would go unarmed. They pointed out that the Yamen might not meet. He replied he could wait—he was taking along a book and a box of good cigars.

So he set out in his sedan chair, accompanied only by his secretary Heinrich Cordes and a few outriders to lend a little prestige. They had just passed the Arch of Honor on Hata Men Street when a Chinese soldier, with peacock feathers in his hat, stepped out from the curb. He pushed a rifle through the window of the Baron’s chair and pulled the trigger.

Minutes later Herr Cordes, wounded and exhausted, staggered into the Methodist compound, where the missionaries were still trying to prepare the schoolgirls to shift for themselves. He shouted that von Ketteler had been assassinated, then collapsed from loss of blood. Runners sped to the legation with the awful news.

Now flight was out of the question. It would simply lead to more massacres. All groups were ordered to the British compound to stand siege until help could come. Again the question arose about saving the Chinese Christians. Again Minister Conger said no: there simply wasn’t room. His colleagues seemed to agree. This was too much for Dr. Morrison, the stalwart Times correspondent: “I should be ashamed to call myself a white man if I could not make a place for these Chinese Christians.”

No answer. So Morrison did something about it himself. With the help of Professor Huberty James, a knowledgeable teacher at Peking University, he wangled the use of Prince Su’s palace, or fu, next to the British Legation. The prince wouldn’t be using it, and (who knew?) the loan might be a good investment if the allies held out. The argument worked, and now there was room for everyone. “Come at once within the Legation lines,” Conger hastily wrote the Methodists; then the wonderful words they could hardly believe: “And bring your Chinese with you.”

The missionaries had only twenty minutes to get ready. Just enough to grab the first thing in sight—one lady settled on a hot-water bottle. Then off on the long trek to the Legation district—71 missionaries, wives and children … 124 native schoolgirls, strangely lamb-faced … 700 Chinese converts staggering under rolls of bedding … 4 stretcher bearers carrying the wounded Herr Cordes … 20 U.S. Marine guards, tramping along in the sleepless way of men who had seen too much duty.

Reaching the Legation district, the party split. The natives turned off into Prince Su’s fu, where 2,000 Catholic converts had already gathered. The missionaries halted briefly at the U.S. Legation; then continued on as arranged, to the British compound.

Here they would be comparatively safe, for Her Majesty’s Legation formed the heart of a good defensive position. To the north was the Hanlin Library; its walls were thick and no one thought the Chinese would wreck its centuries of culture. To the east (across the Imperial Drainage Canal that ran through the whole position) lay Prince Su’s fu—now strongly held by Japanese marines. The southern front was the great Tartar Wall, forty feet thick. American and German marines held a three-hundred-yard segment along the top; and the U.S. detachment seemed in good hands under Captain Jack Myers, a resourceful Georgian who boasted perhaps the best set of whiskers in Marine history. The west side seemed weaker, but the imperial carriage park at least offered an excellent field of fire.

The whole perimeter measured about a mile and a half in circumference. It included most of the legations… various foreign banks and stores … the club … M. Chamot’s beloved Hôtel de Pékin. With luck they could hang on here for a week or so; everything else would have to be sacrificed.

That anyhow was the plan as the Methodists poured into the British compound about noon on June 20. They were the last to arrive, rounding out perhaps the most cosmopolitan garrison in history. Besides the diplomats of eleven different lands, here were scholars, travelers, churchmen, financiers, and statesmen. M. Pokotilov, the mysterious Russian banker, stood muttering to himself, clutching his famous black brief case. Sir Robert Hart seemed lost in thought—perhaps contemplating the wreck of forty years’ service in the Chinese government. Dr. W. A. P. Martin, seventy-one-year-old president of the Imperial University, huddled with Dr. Arthur Smith, whose Chinese Characteristics was the outstanding book in a field they all now confessed they didn’t understand.

Minister Conger’s party made a group in themselves. Mrs. Conger, warmhearted but a bit eccentric, was telling people that the whole trouble lay in their minds. Nevertheless, her daughter Laura remained wildly upset and her friend Mrs. Woodward clearly longed to be back in Chicago.

On a lower official level but feeling far superior socially, the Squiers party watched the Congers with tolerant amusement. The first secretary was immensely stylish in the new, clean-cut Arrow collar man fashion—a complete break with the bearded legions of the nineties. He loved books, ceramics, and fine food. The Squierses lacked essentials like everyone else, but it turned out they had enough champagne for every meal.

The American diplomats and their families were all assigned to the doctor’s quarters, as Sir Claude struggled to sort out his 414 unexpected guests. This was something he could do with astuteness. The difficult French and Russians got houses to themselves. The Germans and Japanese shared the students’ quarters—they seemed to get along well together. The Royal Marines got the fives court. The American missionaries jammed the chapel; the overflow ended up in the loft, floundering among bowling pins, lantern slides and relics from the Diamond Jubilee.

In Sir Claude’s own residence the smoking room became a bachelors’ quarters; the ballroom a ladies’ dormitory. Dr. Morrison and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank shared an open pavilion—all the more crowded because the doctor installed his reference library. Another pavilion served the guests of the Hôtel de Pékin. M. Chamot and his American bride stayed behind in the hotel itself, where they ground flour and ran a sort of catering service for discriminating refugees.

Food was in fact the big problem for everyone. Counting the natives in the fu, there were more than 3,000 people to feed. Yet only the American Methodists had collected any stores and these were abandoned at the mission. Some 150 ponies were quickly rounded up—mostly left over from the spring race meeting. Then a few mules and even a cow.

Several nearby shops were also well stocked, but the ministers weren’t sure of their authority. This didn’t bother Herbert Squiers. In his army days, his scorn for red tape had been the despair of his superiors. Now it came in handy.

As the Chinese deadline approached on the afternoon of June 20, Squiers swept into action. Aided by his fifteen-year-old son Fargo, he collected everything in sight—some sheep he ran across near the British compound … eight thousand bushels of wheat at the Broad Prosperity Grain Shop … tons of rice stored near the Imperial Drainage Canal. The Chinese kept their shops open and accepted with smiles the informal requisition slips. But around 3:00 the shutters rattled down; little strips of red paper signifying Happiness appeared on the slats; and the proprietors simply vanished.

At 4.00 P.M. sharp a Chinese rifle cracked somewhere north of the French Legation. A French sentry fell shot through the head. The siege was on.

Chinese trumpets brayed in chorus as gunfire erupted on all sides. The defenders caught an occasional glimpse of black-turbaned figures darting from wall to wall. These were no Boxer rabble, but trained soldiers with European guns: General Tung Fu-hsiang’s fierce Khansu braves—ten thousand Mohammedan cutthroats feared by even the Chinese. Then the Imperial Bannermen joined in, then Prince Tuan’s “Glorified Tigers,” then Jung Lu’s huge Peking Field Force. Each group had its own garish uniform—the Khansu artillerymen, for instance, sported violet embroidered jackets—but despite their dress, they proved tough, cautious fighters remarkably hard to hit.

The Boxer volunteers were an easier target. Hordes of them moved up for the long-awaited day of reckoning. Screaming curses, waving old flintlocks, muzzle-loaders, spears, tridents, anything—little groups dashed forward in plain sight. If they still felt they were invulnerable, they soon learned otherwise. It didn’t seem to matter. As fast as they fell, new believers took their place.

No one ever knew just how many Chinese there were. As the days passed, the estimate climbed from 80,000 to 100,000 to 360,000. Certainly it seemed that way, but of course the number was less. Perhaps Admiral Kempff was close when he estimated 20,000 Chinese troops, not counting the thousands of Boxers and rioters that joined the attack.

Against them was an official force of 450 legation guards. On the plus side they were generally tough and resourceful—men like Gunner’s Mate Joseph Mitchell, a mechanically gifted sailor from the U.S.S. Newark … Colonel Shiba, the little Japanese dynamo … and the cynical Baron von Rahden of the Russian detachment, who was probably the best shot in the Far East.

But they were so few. Forty-three of the men had already been detailed to help Bishop Favier, holding out in the Peitang Cathedral to the north, and the remaining 407 had poor guns and little ammunition. The Austrians’ machine gun and the Americans’ Colt automatic looked useful, but the Italian one-pounder was a museum piece, and the British Nordenfeldt, 1887 model, had a cute trick of jamming every fourth round.

In this crisis, the foreign colony’s cosmopolitan complexion proved a great asset. There were, it turned out, a good many accomplished military men present. The polished Captain Labrousse of the French Infanterie de Marine had been passing through, on his way from Tongking to Paris by way of Siberia. Nigel Oliphant of the Imperial Chinese Bank once served in the Scots Greys. That chap Vroublevsky, in town to brush up on his Chinese, was actually a lieutenant in the Ninth Eastern Siberian Rifles. In all, some seventy-five refugees turned out to have military talent and were gratefully added to the defense force.

Still, they were few enough, and it seemed a sickening waste when Professor Huberty James was captured at the very start. He had been checking Prince Su’s fu and was returning by the unguarded north bridge over the Imperial Drainage Canal. A little risky, but James loved the Chinese and just couldn’t believe they would harm a European. So they caught him easily and hustled him off into the dusk. Two days later his head was displayed in a cage over Tung Hua Gate.

As darkness ended this first day, some of the besieged were mildly startled to see the Italian Minister Marchese di Selvago Raggi sauntering about in evening dress. Most of them were too miserable to care. The night was stifling … every child wanted a drink of water … the people sprawled on mats and tables seemed to take up far more room than they did in the day. They were apparently arranged just to be tripped over. Outside Chinese bullets criss-crossed the sky, clipping branches from the trees in the hot courtyard.

June 21 was complete confusion. Nothing accomplished; no one in charge. Toward evening Captain Thomann, skipper of the Austrian cruiser Zenta, assumed command by virtue of seniority and a vile temper. The results were almost fatal. On the morning of the 22nd Thomann suddenly ordered everybody back for a last stand in the British Legation. The various marine detachments tumbled in, abandoning the French Legation, the Tartar Wall, all the strong points. There was no Chinese attack at the time, and the order seemed idiotic.

The sheer folly of it all blasted the general apathy. It dawned on the ministers that they weren’t bound by the seniority rules of the Austrian Navy. They fired Thomann and appointed their host, Sir Claude MacDonald. It was a fortunate choice. Whatever his capacity as a diplomat, Sir Claude was trained in the “hollow square” tradition and this crisis was made for him. He rushed the men back to their posts before the astonished Chinese had time to move in.

The next step was to erect some defenses. A difficult problem, for no one, including Sir Claude, knew anything about fortifications. He and the others were gentlemen trained to fight in the open, not build barricades. The solution came from a most unlikely source. It seemed that the Methodist missionary Dr. Gamewell had planned some excellent defenses for their abandoned compound. Could he, Sir Claude inquired, help here? He certainly could. The Reverend Frank Dunlop Gamewell was no ordinary missionary. Raised in a mechanically-minded family—his father invented a fire alarm system—he had gone to both Rensselaer Poly and Cornell Engineering School. He knew everything about construction.

This remarkable find was too good to waste. Sir Claude put Dr. Gamewell in complete charge of the legation’s defenses. He could ignore the whole jerry-built command chain of colonial colonels, gentlemen strategists and obstructive veterans of the American Civil War. From this point on, the defense took a new turn.

Pedaling furiously about on his bicycle, Gamewell seemed everywhere at once. Now he was building a blockhouse by the main gate on the east, now a bombproof for the hospital to the south. The Chinese were beginning to use artillery; this meant stronger earthworks on the north—a seven-foot wall should do. Rumors of Chinese mining on the west—the counter mines should be twelve to fourteen feet deep. And at night his head swam with figures that had nothing to do with missionary work: a Mauser bullet would penetrate one-quarter inch of brick, a Krupp shell fifty-four inches. A thoroughly professional engineer was at work.

Sandbags were needed everywhere, and the women sewed with a vengeance. Caught in the surging spirit, Lady MacDonald donated the legation curtains, sheets, table linen. When these were gone, someone raided Prince Su’s palace, and bags appeared made of costly Ningpo silks and tapestry. A nearby clothing store was searched, and one man found a suit he had ordered but never picked up. He put it on, brought the rest of the stock back for more sandbags.

In the midst of the sewing, a dilemma arose. A sentry announced that the bags were too small—he wouldn’t risk his neck behind protection like that. When the ladies made them larger, a marine complained they now broke too easily.

As usual, it was Dr. Gamewell who resolved the problem. Cycling up from nowhere (he always appeared magically just when you needed him), he jotted down some figures and told the women, “No matter who tells you to do different, follow these measurements.” Then with a polite “good morning” he vanished as swiftly as he had arrived.

Gunfire pounded the new defenses till 11:30 A.M. on June 23, when all fell strangely silent. Suddenly smoke spiraled up from the great Hanlin Library, just north of the legation. Again the enemy had done the unexpected. Until this moment it was assumed that the north was secure, since the Chinese wouldn’t endanger their greatest library. Now they were burning it, trusting the flames would spread to the legation.

The alarm bell on Jubilee Tower clanged wildly. All ages raced to the danger spot. While sharpshooters gave covering fire, volunteers dashed into the Hanlin property and hacked at the burning walls, trying to clear away the sections nearest the legation. Bucket brigades formed to help check the flames. Madame Pichon, wife of the French minister, toiled next to a coolie. Mrs. Conger’s party of ladies worked as a team. The resourceful Lady MacDonald supplied them with basins, kettles, pans, finally dozens of chamber pots with which the legation was amazingly well supplied.

The battle looked hopeless. The flames roared skyward, feeding on the Hanlin’s priceless collection of scrolls and documents. In the compound, children beat at the embers that showered down. On a rockery high in the Forbidden City the Empress Dowager watched with interest, while her current favorite General Tung Fu-hsiang purred assurances that the end was near for the foreign devils.

Perhaps it was a change in wind … or the courage that can keep men trying when logic says all is lost. In any case, twilight found the Hanlin in ashes, but the British Legation still intact.

The 24th was the first Sunday under siege, and someone hesitantly asked the Reverend Gamewell, “Are you going to stop?”

“The most worshipful thing,” he answered, “the divinest thing to do today is to stretch every nerve to protect these women and children.”

Just as well, for it turned out to be a harrowing day. To the north and east, the Chinese battered at Prince Su’s fu, and the Japanese barely hung on. To the south, the Russian Bank was blown up and the American compound almost captured. On top of the broad Tartar Wall, hordes of Chinese prepared to sweep the German and American marines off the vital segment bordering the Legation District. If that went, enemy guns would command the whole position. Somehow the marines kept the Chinese off balance until this barricade could be strengthened. The British Legation itself was attacked from the west. Again, the fires … again, the clanging alarm bell … again, the bucket brigades. This time they faced an added hazard; the Chinese were now so close they lobbed hot bricks over the legation wall. The emergency hospital in the Chancellery filled faster.

They struggled on. June 25, their first horsemeat … one of Sir Claude’s racing ponies. June 26, U.S. Marine Sergeant Fanning died fighting on the Tartar Wall—neither the first nor the last to go, but he had a jaunty touch that would be missed. June 27, the William Moores had a baby; Dr. Martin, who had a healthy streak of ham, told them to call the child “Siege” because it ought to be raised.

There was a trace of the Old Breed in them all. The Squierses solemnly discussed vintage wines. Miss Cecile Payen, one of Mrs. Conger’s guests, pulled out her water colors and began sketching. An English Customs Volunteer sat under fire in the fu, teaching a Japanese marine tick-tack-toe. The militarily inept formed a company of irregulars called “Thornhill’s Roughs.” They armed themselves with anything left over—one had a fusil de chasse decorated with a picture of the Grand Prix.

All the time, their plight grew more serious. And the Chinese always excelled at the tactics that were most nerve-racking—clusters of flaming arrows, sky rockets, hot bricks that showered down from nowhere. Occasionally Boxer fanatics dashed up to the walls carrying bamboo poles with kerosene-soaked rags tied to the end. Usually they were stopped, but sometimes flames mushroomed skyward. The Imperial troops proved poor artillerymen but excellent at using their pet “gingals”—huge two-man guns, sometimes ten feet long, which were aimed like rifles. The shooting, the yelling, the blare of trumpets never seemed to end.

At night the women were especially terrified. Dr. Gamewell understood perfectly, and no matter how busy he was, he always had time to give them a word of encouragement. Standing bashfully outside Lady MacDonald’s ballroom, where some of the Methodist ladies were quartered, he would call into the dark, “It’s all right—it’s never as bad as it sounds.”

Welcome words, but as night after night passed with no let up—as day after day the casualties mounted—the besieged began to wonder. How long would they be able to last?

Up to this point, there had been no doubt. They could last until relief came. Admiral Seymour should arrive any day, and in fact, every night the men watching the southern horizon saw hopeful signs. On June 26, the Japanese thought they saw their army’s rockets. On June 30, a German officer thought he saw a German naval searchlight. Sir Claude knew the man was wrong: it was clearly a British light. Next morning he posted the following announcement on the community bulletin board by the Jubilee Tower: “This morning at about two o’clock I saw the searchlight of Her Majesty’s ship Terrible. I recognized it as the searchlight of that ship because it has a very characteristic searchlight.”

But the days passed and nobody came. Worse, the messengers that were lowered over the Tartar Wall to make contact just disappeared. Why didn’t they carry out their mission and come back as instructed? Where was Seymour anyhow? What was the matter with everybody?

July 2 brought one of those near-disasters that can make men forget all about self-pity. The Chinese almost drove the Americans off their segment of the Tartar Wall. Enemy barricades went up within twenty-five feet of the Marines, pinning them down completely. Something had to be done right away, or the wall—and everything else—would be lost.

Just before dawn on the 3rd, Captain Jack Myers assembled a small force behind the threatened position. Around him crouched his fourteen American Marines, fifteen Russians, and twenty-six British. A few yards away the Chinese barricade loomed black and ominous in the early-morning light. It was a dramatic situation—made for a man like Myers. He leaned toward amateur theatricals and only recently had courted serious trouble with a satire on the Kaiser.

Now he worked his men up to fever pitch. He told them that the Chinese position must be taken … that the odds were against them … but the life of every woman and child depended on their success. Young Oliphant of the British volunteers thought the whole performance was a bit overdone, but most of the men were tremendously moved. When Myers ended with a shout to charge, they swept forward with a yell, completely routing the surprised Chinese. Two marines were killed in the charge, and Captain Myers tripped over a spear, wounding his knee. He would be out of action indefinitely, but the day was saved.

The victory really made the Fourth of July for the American colony. Previously there had been some rather pointed remarks that the famous U.S. Marines seemed strangely cautious. Now the legation staff proudly celebrated the day with little flags in their lapels. Minister Conger showed everyone the framed copy of the Declaration of Independence that hung in his office—a bullet had pierced the lines that criticized George III. It was quite a conversation piece. Mrs. Conger meanwhile slipped quietly to the little plot where six marines now lay buried. Gently she covered the graves with a silk American flag.

It was a day to think of home—especially for the bereaved Baroness von Ketteler. A lot had happened since she was plain Maud Ledyard, daughter of the president of the Michigan Central Railroad. She had married the titled aristocrat, traveled over the world, faithfully followed the success formula for a wealthy American girl—and what a bleak future now. Miles from home, her husband killed, her own life in danger, no one to turn to except the unbearably correct German Legation staff. In the gray hours of dawn she would stand at her window, pale and grief-stricken. Once she turned and caught the arm of Mrs. Frank Gamewell, who happened to be passing. “I am so alone,” she said.

Another time the baroness stopped Mrs. Conger. “No title, no position, no money can help us here,” she sighed; “these things mock us.” Even Sir Claude might have agreed the day a Chinese cannon ball crashed into the legation’s state dining room, grazing the Queen’s portrait.

To maintain some pretense of return fire, the defenders desperately kept shifting their four guns. In a single week the Italian one-pounder was used at the British stables, the Tartar Wall, the legation library, the fu, the Hanlin earthwork, the fu again, the stables again, and finally the main gate.

Then came the happy discovery of an old Chinese gun barrel, 1860 vintage, lying in a blacksmith shop within the lines. It was immediately appropriated by Gunner’s Mate Mitchell, the inventive American sailor. He took a Welshman named Thomas into his confidence, and together they built a whole new cannon. It turned out to be a remarkable mongrel—Chinese barrel, Italian carriage, Russian ammunition, British and American crew. Sensing symbolic implications, the English christened it “The International Gun.” The earthier Americans called it “Old Betsy” and sometimes just “the old crock.” Whatever the name, its performance was eye-opening. When formally christened on July 8, the first cannon ball went through three walls. True, it wasn’t very accurate, the recoil was terrific, and it always looked as if it might explode. But its devastating roar made up for everything, and Mitchell was the hero of the hour.

He was in for still greater glory. On July 12 Chinese troops in the Hanlin moved up so close that they leaned their banner against the British Legation wall. This piece of impudence was too much for Mitchell. He leaned over the wall and hooked the flag. A Chinese soldier grabbed the other end, and for a few moments all firing stopped while both sides watched a monumental tug of war. With his free hand, Mitchell slung fistfuls of dirt at the Chinese, who finally had to let go. The red and black banner was torn to shreds, but Mitchell happily clutched it when he plunged back into the compound.

Through it all, the children of the American missionaries held their own tugs of war, built their own little forts, played their own games of “Boxer”—oblivious of the peril around them. One of the group, Carrington Goodrich, still remembers side-stepping a real cannon ball that bounded into some game of make-believe.

There were endless close calls—none more frightening than the time Polly Condit Smith sat near the tennis court, trying to cheer up the Baroness von Ketteler. A sniper’s bullet whistled by, and Miss Condit Smith dived for the ground, trying to pull the Baroness after her. But the heartbroken widow refused to budge, and a hail of bullets clipped the trees and grass around her. She was still rooted—trying to die—when a customs volunteer rushed to the scene and carried her to safety.

It must have made an exciting story at the Squiers breakfast table the following morning, where the more sophisticated liked to relax a minute before facing the day’s ordeal. Besides Polly Condit Smith, the guests usually included Dr. Morrison of the Times, the charming Captain Strouts of the British guard, and more recently Dr. Frank Gamewell. He, however, rarely joined in the conversation. He simply sat for a moment, gulping coffee and listening to the others. Then he was off on his bicycle again, pedaling to some new danger point.

By mid-July this was most likely to be the French legation. For some days the defenders there had heard ominous clicks and taps in the ground beneath them. Then, just after 6 P.M. on the 13th, a tremendous blast seared the fading twilight. Flames and smoke shot into the air; bricks and sandbags rained down on the defenders. The mine blew two men to bits, wounded several others. Professor Destalon, a volunteer from the Imperial University, was buried in the debris, then released unhurt by a second blast. The French marines grimly dug into the ruins, somehow managed to hold the position.

Next there was trouble again on the Tartar Wall. Captain Newt H. Hall, the U.S. Marine who had taken over from the wounded Jack Myers, found the enemy fire getting constantly heavier. When Herbert Squiers ordered him to move his barricades even closer to the Chinese, he just couldn’t see it. And when Minister Conger supported Squiers, he still couldn’t see it. They were indeed a strange pair of military superiors: even an affectionate biographer confessed that Conger’s Civil War record was undistinguished, while Squiers had spent fourteen years as a second lieutenant. Perhaps a clever talker like Myers could have side-tracked their strategy, but Hall was the stolid, tactless type and he plainly showed his contempt.

Squiers finally climbed the wall on July 15 and showed Hall exactly where he wanted the new barricade. That night Hall reconnoitered the place, but ended up keeping his men further back at their old position. Other men were later posted at the new spot, and it didn’t help Hall in the months to come when it turned out that Squiers and Conger, the dabbling amateurs, had been right. The advanced position could indeed be held and helped the defense immensely.

So many of the bold spirits, the best men, were now gone. On the 15th Henry Warren, a bright young consular student, was killed in the fu. Early on the 16th Henry Fischer, one of the finest American Marines, fell on the Tartar Wall. It was a heartbroken group that gathered that morning at the Squierses’ for breakfast. Morrison and Strouts briefly picked at their food, then went to help out in the fu.

It was about 8:30 when they were both brought back—Morrison badly hit, Strouts mortally wounded. The dying captain held out a limp, white hand to Polly Condit Smith. She could only think of that same hand, firm and vigorous, reaching for a cup of coffee just an hour ago.

A gloomy drizzle fell as they buried Strouts and Warren late that afternoon. Most of the legation colony stood at the graveside, when a most unexpected development interrupted the service. A messenger burst through the crowd and handed Minister Conger a letter. The mourners quickly forgot the funeral as they recognized the familiar red envelope used by the Yamen. They crowded around Conger, who ripped out a cable in State Department code. Translated, the message said simply, “Communicate tydings bearer.”

It was clearly authentic. No one else had access to the code. (And good cryptanalysis lay in the future.) But who sent the message? When was it sent? Who was “bearer”? And assuming it originated in Washington, how did it come?

Actually, the message came through Wu Ting Fang, the Chinese minister to Washington. Totally isolated from the archaic capital that supplied his credentials, Wu was working on his own for peace. He had no friends—no bloc of sympathetic powers, no support from “world opinion”—he was completely alone. Nevertheless he achieved a miracle. Specifically, he persuaded the State Department to send the cable and the Yamen to deliver it.

At the moment, Conger knew none of this, only that it was genuine. He worked up a brief answer in the same code, outlining the situation and the urgent need for help. Perhaps his reply would never be forwarded, but he had nothing to lose. There was no sign of the Seymour relief force or that any of the earlier appeals had gone through. This at least meant another chance.

It also meant that at least some Chinese might be interested in talking peace. There had been signs of this before. As early as June 25 a board had appeared on the canal bridge suggesting a cease-fire; at the time it seemed like a ruse. Then on July 14 a letter signed “Prince Ching and Others” arrived, requesting that the ministers and their families move to the Yamen where they would be protected until they could be sent home. Nobody had any intention of leaving the fortified legations, but the message did indicate divided councils at the Imperial Palace. Another friendly letter and now the cable for Mr. Conger seemed further evidence. The ministers cautiously suggested that if the Chinese were in earnest, a cease-fire would be the best way to show it.

“Now that there is mutual agreement that there is to be no more fighting,” replied Prince Ching and Others, “there may be peace and quiet.” With that, a rickety, uneasy truce began on July 17.

The Chinese proved as baffling as ever. They abducted M. Pelliot, a Frenchman from Tongking, but he later returned smiling, having had tea with General Jung Lu. Several cartloads of melons arrived from Prince Ching and Others. Another shipment came with the Empress Dowager’s compliments—followed by a message apologizing that they had been delivered to the wrong address. Chinese soldiers conducted a lively black market first in eggs, then in ammunition.

Information was also for sale, at not too reasonable rates. But the purveyors knew just what the customers wanted, and a steady stream of glowing reports poured in, describing brilliant Allied victories, the relief force steadily approaching, the Chinese and Boxers hopelessly routed. The besieged, who had long given up on Admiral Seymour, once more scanned the southern horizon … once again imagined they saw searchlights and rockets in the sky.

They had their first word from the outside on July 18. A messenger sent out by the Japanese at the end of June returned to report that a mixed relief force of thirteen thousand would leave Tientsin on July 20. It was cheering to know that help was really coming, depressing to learn that nothing had happened for a month.

The days dragged by, then another messenger on July 28. It was a fifteen-year-old native Sunday-school student the American missionaries had lowered from the Tartar Wall on July 4. Disguised as a beggar, he made it safely to Tientsin; now he was back with a letter for Sir Claude from the British consul. It couldn’t have been more discouraging. As of July 22, the relief force hadn’t even been organized. “There are plenty of troops on the way,” the message vaguely concluded, “if you can keep yourselves in food.”

But that was just the problem. Food was running out. Could they last long enough for these apathetic rescuers? The Committee on Food Supply—by now there was a committee for everything—took stock on August 1. They figured there was enough to give each person one pound of wheat and one-third pound of rice a day for nine days. Or five weeks, if they cut out the 2,750 native Christians in the fu—and as conditions grew worse that thought occurred to surprisingly many.

Hunger could do strange things. One evening as Polly Condit Smith strolled beside the Dutch Minister Herr Knobel, they suddenly heard a hen clucking. It clearly belonged to a nearby family of Russians, but that didn’t faze Knobel. He quickly pounced on it, and with the bird loudly squawking under his coat, the diplomat and the lady raced away through the dark, like any pair of thieves.

On August 7, they all went on half rations. Worse, there was no milk left for the children. And conditions in the fu were now appalling. No one quite stooped to cutting off the converts, but they certainly didn’t get an equal share. The children died faster, and many of the adults could only crawl. Leaves were stripped from the trees, cats ruthlessly hunted down, and the kindly Reverend Martin found himself telling Miss Payen that the Chinese liked to eat dogs anyhow.

To cheer themselves up, the American missionaries tried some hymns one night on the steps of the Jubilee Tower. Next a few numbers like “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys Are Marching.” Then, in honor of some French marines, a rather shaky “Marseillaise.” It became a regular occasion after that, with each country singing its own songs. The Russians offered the added attraction of Madame Pokotilov, wife of the head of the Russo-Chinese Bank. She had been a diva at the St. Petersburg Opera House, and one evening let go with such a rousing interpretation of the Jewel Song from Faust that the Chinese fired a volley in her general direction.

The truce was often broken and had collapsed altogether by August 9. A new Shansi regiment took over the attack. They had the latest repeating rifles and swore to finish the foreigners off, “leaving neither fowl nor dog.” They swept through the Mongol market on the west, wavered before a blazing return fire, and finally fell back among the ruined huts and shanties.

Word came on the tenth that the relief force was at last under way. It had left Tientsin on August 4, and a message from the commander, General Gaselee, said cheerfully, “Keep up your spirits.” More practical was the succinct letter that also arrived from the leader of the Japanese contingent, General Fukushima, who explained that the relief force would approach from the east and ended with the all-important words: “Probable date of arrival at Peking August 13 or 14.”

It was the message they had been waiting, praying, and fighting for, but ironically the defenders had little time to celebrate. They were now too hard pressed. The Chinese seemed determined to crush the legations before help arrived.

The nerves of the besieged wore thin. Some of the American missionaries began squabbling—for a while no Methodist would pull the punka while the Congregationalists ate. Several of Mrs. Conger’s ladies lost their temper when a squad of dog-tired U.S. Marines didn’t stand up and salute them. (Captain Myers had taught them to do it so nicely, and this Captain Hall said they needed to rest.) The ladies took their complaint to the minister, who made a mental note of the incident.

Now it was Monday, August 13. That evening the Chinese attacked as never before. Tough old Gunner’s Mate Mitchell feverishly worked “Betsy”—and then suddenly fell, his arm shattered. The Reverend Gamewell dashed from station to station, shoring up the shredding defenses, all the time gulping the coffee he drank to keep going. In the fu, the Japanese and Italians reeled backward. Colonel Shiba had his men bang pots and pans to make his force seem larger—somehow they hung on. In the Mongol market, the Shansi regiments again stormed the west wall of the British Legation. As the bell on Jubilee Tower clanged for a general attack, the tired men and women rushed once more to the stations. Even Sir Claude dashed to the wall—and just as well, for a Krupp shell ripped into his dressing room.

A few yards away the Chinese officers were urging on their men: “Don’t be afraid, don’t be afraid—we can get through!” But they couldn’t. The regiments melted. The men drifted back. About 2:15 A.M. the firing fell off.

Rising above it, a new sound was heard—a faint rumble far to the east. Soon it was louder, and reflected light occasionally danced and flickered along the horizon. Much closer, a machine gun began hammering. The defenders could hardly believe it was true.

“They’re coming!” a sentry yelled, bursting into Dr. Martin’s quarters.

“Get up, get up! Listen to the guns! The troops have come!” cried Señor de Cologan, the Spanish minister, rushing down the cluttered men’s corridor in Sir Claude’s residence.

“They are really here,” Dr. Gamewell told the missionary ladies sprawled on the floor of the ballroom.

Out of the buildings they poured, happily listening to the gunfire that rolled louder and louder from the east. The ladies at the church served coffee and cocoa—they could be free with it now. The gentlemen began betting on the exact time the relief force would arrive. They were still in little groups, talking, laughing, always listening, long after the sun rose.

During the morning Captain Hall watched shells falling on the Tung Pien gate, where troops were clearly trying to smash their way through. From a distance, it looked like slow going, and Hall scoffed at one of the customs volunteers, who thought he saw foreign troops in the outer city. But it was true. While the Japanese, Russians, and Americans battered at other gates, the British had broken through the almost undefended Sha K’ou gate to the southeast. Now they were cautiously moving toward the huge Tartar Wall.

They knew just where to go, for the American segment of the wall was marked by flags. More important, they knew what to do when they got there, for a message from Sir Claude had told them about the little-known sluice gate of the Imperial Drainage Canal. The main gates in the wall were all held by the Chinese, but the sluice gate was in the American segment. Once through, they could follow the canal straight to the British Legation.

The 7th Rajputs burst past the rotten wooden gate about 2:30 P.M.—the first unit in. Up the nearly dry canal they raced, sliding in the mud, tripping over each other, scrambling to be first at the legation. The defenders heard them and rushed to the canal bank to meet them. The two groups swept into each other’s arms, hugged and danced and cried together. Sir Claude tried to lead a cheer, but his voice choked.

It was a supremely rewarding moment, but one of the defenders missed it completely. As the relief force swarmed over the legation tennis court, the Reverend Frank Gamewell was on the north barricade, still hard at work arranging his sandbags, planning his loopholes, bolstering his defenses—a thorough professional to the end.

To the south, more troops were pouring in: the First Sikhs … the 24th Punjabs … the First Bengal Lancers … the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. Then General Gaselee himself, gallantly embracing Mrs. Squiers and Polly Condit Smith. (“Thank God, men, here are two women alive!”) It all seemed right out of Kipling.

The arrival of the American troops was less romantic. They spent a desperate morning, pinned down by fire from the outer city wall. Finally, musician Calvin P. Titus cleared the way by leading a scaling party up the bare face of the wall—an incredible feat ultimately rewarded by the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Once the wall was cleared, the 14th Infantry pushed on into the outer city, but even now the men found the going slow. It was 4:30 by the time General Chaffee finally approached the sluice gate. Prancing ahead of his men on a charger, he looked curiously like a toy soldier.

From the top of the Tartar Wall an American marine called down to the general: “You’re just in time. We need you in our business.”

Letting this one pass, Chaffee asked, “Where can we get in?”

“Through the canal,” the marine shouted back. “The British did it two hours ago.”

Actually, there was no need to feel left out. For the winner there’s always enough glory for all, and Chaffee’s reception was as wild as the British. For the rest of the day everyone simply traded congratulations and compared experiences. The besieged learned how the Boxers had thrown back Admiral Seymour in June; how the allies had fought for weeks to hold Tientsin itself. They apparently owed much of their success to fortifications designed by a young engineer named Herbert Hoover.

The relief force listened with awe to the epic of the siege, and indeed it was something to be proud of. For 55 days some 480 men had held off at least 20,000. The casualty figures alone showed their peril and bravery: 234 men—49 per cent of the defense force—were killed and wounded.

In the general rejoicing, the besieged briefly forgave the combination of timidity, jealousy, and red tape that delayed Gaselee’s force an extra month. For their part, the rescuers forgot the myopia in Peking that lulled and misled them right up to the siege. That night they wanted only to wallow in victory, and at the battered Hôtel de Pékin M. Chamot sensed the mood perfectly. Like the good innkeeper he was, he magically produced champagne for everybody.

Next day General Gaselee’s men began mopping up. They relieved the isolated Peitang Cathedral, where Bishop Favier had successfully held out. They chased the Empress Dowager, but that crafty old lady eluded them easily, disappearing to the north as they came in from the South. They broke into the Imperial City, then into the palace and the Forbidden City itself, but no one important was there. They fanned out over the country, executed a few Boxers, pulled down some walls, but all the Chinese who mattered were gone. And finally they looted—homes, shops, temples, palaces. Boxer or not, it made little difference. When one Pekinese implored an American soldier to write a notice that would keep out looters, the soldier gladly complied: “USA boys—plenty of whiskey and tobacco in here.”

The months that followed were spent by the diplomats in negotiations with the defeated Empress Dowager; by the soldiers in endless reviews, trooping of the colors, and pleasant afternoons taking pictures of one another in the sacred Forbidden City.

The rest of the world shared in their joy. During the dark days of June and July, Peking had been given up for lost, and it was only natural to feel exhilarated now.

The way the great powers co-operated was especially heartening. It seemed to point toward a new era, when countries would forget their rivalries and join together on great projects. Only the tired, weary Viennese couldn’t see it. As early as September 3 the Austrian papers predicted that now the danger was over, the clashes would start anew.

Above all, the victory reaffirmed people’s faith in the natural supremacy of the Occidental. “History has repeated itself,” exulted the London Times. “Once more a small segment of the civilized world, cut off and surrounded by an Asiatic horde, has exhibited those high moral qualities the lack of which renders mere numbers powerless.” It was all the more intoxicating because there had been some doubts: during July the New York Times had announced with surprise, “CHINESE CAN SHOOT STRAIGHT.” But now the stars were back on their course.

How did the Japanese fit into this concept? Very easily. Everyone called them “plucky,” and they were treated as a phenomenon totally apart from the whole system of racial relationships. The correspondents managed to convey the impression that the Japanese were just like little people.

To the Americans and British, of course, Western supremacy really meant Anglo-American supremacy. “From the first,” wrote Dr. Arthur Smith, one of the besieged scholars, “there was a marked contrast between the Anglo-Saxons and many of the Continentals, who for the most part sat at case on their shady verandahs, chatting, smoking cigarettes and sipping wine; while their more energetic comrades threw off their coats, plunging into the whirl of work and the tug of toil with the joy of battle inherited from ancestors who lived a millennium and a half ago.” (This was a little difficult to reconcile with the casualty figures: American and British 50, Continental Europeans 145.)

For America there was a final, special satisfaction. It went together with winning the 1900 Olympics and J. Pierpont Morgan’s ventures into international finance. It was the thrill of being an equal partner in the world’s triumphs and problems; it was the pride of having arrived.

So the anti-imperialists were routed. They dwindled to a few sweet ladies like Isabel Strong, who worried about the first bar opening in Samoa; or to a few old curmudgeons like Richard Crocker, who complained about “the fashion of shooting everybody who doesn’t speak English.” In the 1900 presidential election William Jennings Bryan, running against imperialism, couldn’t even carry his own state, city, or precinct.

Right-thinking men believed that “assimilation”—everyone agreed that imperialism was an ugly word—was an economic opportunity, a moral duty, God’s will, and clearly the virile thing to do. As Princeton’s young Woodrow Wilson observed, expansion was “the natural and wholesome impulse which comes with a consciousness of matured strength.”

President McKinley, that kindest of men, believed there was even more to expansion than that—it was the least we could do for less fortunate peoples. On the question of annexing the Philippines, he had prayed to God for guidance, and it came to him in the night: “There was nothing left to do but to take them all and to educate the Filipinos and uplift and Christianize them and by God’s grace to do the very best we could by them as our fellowmen for whom Christ also died.”

So it was with a sense of moral obligation—almost as one owing a debt to his Maker—that McKinley undertook his domestic travels as leader of a new America.