EVER SINCE ADAM HAD WATCHED SHAWN play varsity football in Lake Hamilton High School’s Wolf Stadium under the Friday night lights, it had been his “field of dreams.”

Walking the sidelines as an eleven-year-old ball boy, Adam had fantasized about the day he would suit up, clash against their rivals, and earn his own “stick marks”—multicolored paint streaks on his maroon helmet from colliding with the helmets of opposing schools’ teams. To paint over them was sacrilege.

In the summer of 1989, Adam finally stepped onto the grass at Wolf Stadium as a player. It was eight o’clock in the morning and already ninety degrees, with T-shirt-soaking humidity, when assistant coach Steve Anderson surveyed the talent that had shown up for practice. Coach Anderson, the offensive line coach at Lake Hamilton, had his eyes peeled for players like Shawn Brown, who was now playing college ball on a partial scholarship at Henderson State University in nearby Arkadelphia. He’d seen the name Adam Brown on the junior varsity roster and wondered if their enthusiastic ball boy from two years before had finally put some meat on his bones.

Adam’s beaming smile was unmistakable. So was his size; Coach Anderson doubted he’d grown at all since eighth grade. Even with pads on, Adam looked like “an itty bitty kid,” says Coach Anderson. “All helmet.”

Toward the end of their first practice, the coaches laid two blocking dummies side by side on the grass, creating a lane or “alley,” and both junior varsity and varsity gathered around to cheer on their buddies during “Alley Drill.” First a coach called out two equal-size players, who faced each other in three-point stances. The whistle blew and they sprang forward, collided, and tried to either bowl each other over or muscle each other out of the alley. “It’s a very physical drill,” says Coach Anderson, “a gut check. Football’s a testosterone sport, and the guys are up there to prove their manhood and who can beat who.”

Historically, the big guys—linemen, linebackers, running backs—gravitated toward this drill while the less aggressive and less meaty types prayed they wouldn’t get called out. The junior varsity guys hung back as far as they could, quiet with the crickets.

Except Adam. Just as in his peewee football days with Coach Nitro’s “Blood Alley,” he was up front day after day, begging the coaches to put him in against the bigger varsity players. “C’mon, c’mon, let me take this one. I got it,” he’d yell. The coaches, whose job included not letting the kids hurt themselves, never called on Adam and he’d ultimately stomp off angry.

“Every day he’d give it a shot,” says Coach Anderson, “until finally, toward the end of summer, he wore us down.”

The usually boisterous team lining the alley was almost silent as Adam faced off against one of the bigger varsity linemen. “On the whistle, they crashed into each other,” says Coach Anderson. “Adam did fire out, but this guy hit him hard, drove him back harder, and rolled him up.”

Fully expecting Adam to limp to the back of the line, Coach Anderson blew the whistle. Instead, Adam jumped up, slapped the side of his helmet, and said, “Let’s go again! You want some more of me?”

The coaches looked at each other, and the team responded with a cry of “Let him go!”

Again Adam was pummeled, and again “he popped back up and jumped into his three-point stance, like he wasn’t going to take no for an answer,” says Coach Anderson.

“Let’s go again—I’m gonna whip you this time,” Adam grunted through his mouthpiece.

After the third time, the coaches called the drill, surprised that Adam wasn’t beat up enough to stop on his own. Before heading off the field, Adam ran over to the offensive lineman he’d been pitted against and thanked him for not going easy on him.

The four coaches present that day knew they’d witnessed something remarkable. Says Coach Anderson, “That one little sophomore taught our whole team more about character in a few minutes than any of us coaches could have in an entire season. He wasn’t going to be the big star lineman that his brother was, but what impressed me was this kid was not scared. He was determined that he was not going to let his size keep him from doing whatever he wanted to do.”

Adam’s tough, daring reputation was rivaled only by his propensity for kindness. He went out of his way to give Richie Holden, the boy with Down syndrome, a high-five whenever he saw him. At school functions he’d ask the wallflowers to dance, and there wasn’t a woman in Hot Springs who opened a door for herself if Adam was in the vicinity. And he always stood up for the underdog—never realizing that because of his size he was one himself.

Just before tenth grade started, Adam was invited to a boat party at the Buschmanns’ lake house. Despite the fact Jeff had become one of Adam’s closest friends, Janice was having reservations about allowing her fifteen-year-old son to attend. To say Janice neither trusted Adam’s swimming ability nor liked the idea of a bunch of teenagers in boats out on the lake was an understatement, but he begged until she agreed he could go—as long as he wore a life jacket. He promised he would.

A couple dozen guys and girls partied in the warm summer waters Lake Hamilton style, on a flotilla of pontoon boats and speed boats, various inflatables or skis in tow. With ice chests overflowing with cold drinks and music blaring, the girls sunbathed and the guys showed off with backflips. And in the middle of it all was Adam, life jacket fastened securely. His buddies taunted him, “Dude, Adam, your mom’s not here!” To which Adam replied, “Naw. It’s no big deal. I promised.”

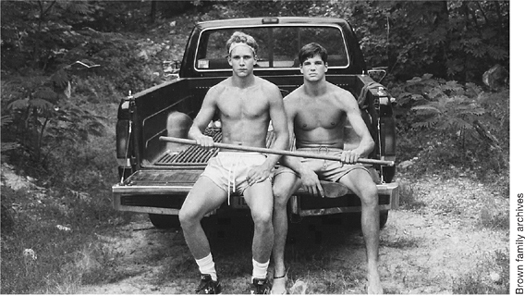

Jeff Buschmann and Adam after running a logging road in the Ouachita woods. Jeff recalls that the stick had something to do with fending off rattlesnakes.

“Adam was like no other kid I ever met,” says Roger Buschmann, who was privy to Adam’s resolve that day. He was even more impressed a few months later when Adam was one of five buddies invited to the Buschmann home for a sleepover. “At two in the morning I heard a knock on our bedroom door,” he says. “It was Adam, holding a phone. Ends up the boys had snuck out to crash a girls’ slumber party but got caught by the mother, who was not pleased when she called me to come get them.”

As Roger Buschmann was leaving the house, he asked Adam why he hadn’t gone with his buddies.

“My parents told me not to leave the house without permission, sir.”

They might be able to out-party Adam, but none of his buddies could beat his crazy stunts. While they’d all jump from the 70 West bridge forty feet into the lake, Adam would add flips and gainers, a forward dive with a reverse rotation. At football camp he was the undisputed belly-flop king, doing five in a row—off the high board.

Then there was his penchant for jumping into (not out of) trees. On his first attempt off a twenty-five-foot-tall bridge into a thirty-foot elm, he missed entirely the branch he was aiming for. The one he did hit snapped, along with others that slowed his fall to the base of the tree, where he landed feet first, a shower of leaves fluttering down around him.

Figuring he’d chosen the wrong genus of tree, Adam tried leaping into a large evergreen off the second-floor deck of a friend’s house a few weeks later. The branch bowed under his weight, then broke. Jeff Buschmann, on hand to witness the carnage, heard a succession of grunts as Adam hit branch after branch on his way down.

“Please don’t do that again,” he told Adam, who walked away bruised but not broken. “You’re going to hurt yourself.”

Adam considered his friends—including Jeff, Heath Vance, and Richard Williams—an extension of his family, and they bonded like brothers in what all of them felt was an idyllic country-boy upbringing. Playing football, swimming and boating in the lake, hiking in the woods, making out with girls, drinking beer, having bonfires, backyard basketball games, house parties, and fistfights—usually with each other—and pulling pranks.

One night when they were sixteen, Jeff, Richard, and Adam rolled a house in an entire case of toilet paper, then tore through the woods to get back to the car they’d left discreetly parked on a different street. Their escape was almost complete when a dark figure materialized by the car, waiting patiently.

Moments later, they were in the backseat of a police cruiser, Jeff and Richard squeezed in on either side of Adam, who kept saying, “My momma and daddy are going to be so disappointed.”

“He started crying like a baby,” says Richard, “and Buschmann looks over at him and says, ‘Adam! Stop your crying! Don’t you have any more respect for your father than that?’ ”

He cried most of the way to the station, and when Larry showed up, he started again. Early the following morning Larry drove him over to the house to help clean up the mess with the other culprits. No other discipline was necessary, because “the ride in the police car did the trick,” says Janice. “He apologized for weeks.”

At the beginning of the summer before their senior year, Adam sat down with Jeff, Heath, Richard, and a few of the other varsity football players. In one year Adam had shot up to almost six feet out of the six foot two he’d eventually reach. He was lean and lanky and, on the field, anything but graceful. “He was proof that you didn’t have to be the biggest or the fastest to be a leader,” says Richard. “It was his heart—his spirit—that drew people to him.”

Indeed, Adam was passionate about his final year as a Wolf. In his junior year, they’d made it to the state semifinals, which wasn’t bad, but Adam was emphatic: if they really wanted to put Lake Hamilton High on the map, they needed to make the finals. The only way to accomplish that would be to work out, eat right, not drink a drop of beer, and hold conditioning practices on their own before the start of the football season. A pact was made, and to the beat of songs like “Kickstart My Heart” by Mötley Crüe and “Eye of the Tiger” by Survivor, the teammates pumped iron in the weight room, ran the bleachers and did wind sprints, and cranked out push-ups, sit-ups, and leg lifts.

When the official two-a-day practices began in late August, “We were stunned by the team’s level of fitness,” says Coach Anderson.

“We would have been mediocre that season if we hadn’t rallied the way we did,” says Richard. “It took leaders like Adam to inspire so many guys to get out there and sweat their summer away for a long shot.”

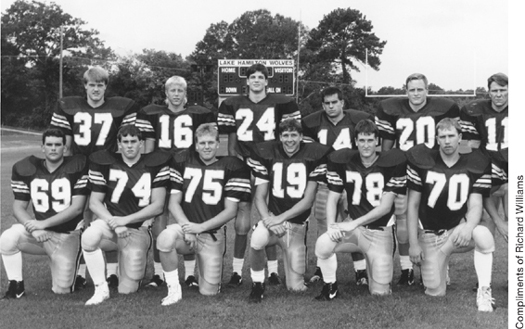

The Lake Hamilton Wolves won their first game. Then their second, and third—and they kept winning, all but one game, landing them in the state finals and inspiring Adam to shave his jersey number, 24, into the cropped sides of his mullet.

Although the team ultimately lost the state championship, as Arkansas State runner-up champions, it surpassed everyone’s expectations and earned bragging rights throughout Garland County. The 1991 Wolves would forever be remembered as the players who put Lake Hamilton on the high school football map in Arkansas.

Over the Christmas holiday break, Richard and Adam were watching a video at the Williamses’ house when they saw an action-packed preview for the movie Navy SEALs, which began with Lieutenant Dale Hawkins (played by Charlie Sheen) jumping from the back of a speeding Jeep off a highway bridge into water at least fifty feet below. This spectacular stunt was followed by gunfire, explosions, and a deep, melodramatic voiceover and monologue: “When danger is its own reward, there are men who will go anywhere, dare anything. They’re Navy SEALs, a unique fighting force who doesn’t know how to lose.… Navy SEALs get paid to take risks; they’re paid to die if necessary.… Together they are America’s designated hitters against terrorism. Born to risk, trained to win … Navy SEALs …”

In 1991, the Lake Hamilton Wolves seniors led the team in a historic season to become runner-up Arkansas State champions; #24 Adam, #20 Heath Vance, #19 Jeff Buschmann, and #16 Richard Williams.

Danger is its own reward? Go anywhere, dare anything? Hell, Richard thought immediately, they aren’t talking about the Navy SEALs—they’re talking about Adam.

Adam, on the other hand, was most inspired by the stunt. “I’m gonna do that,” he said to Richard. “I’m going to jump out of a car when we’re crossing the 70 West bridge.”

“You’re crazy,” said Richard.

As senior year progressed, every time Adam drove across the bridge, he brought the topic up to whichever buddies he was with.

“We all jumped off that bridge,” Jeff says, “but to do it from a speeding vehicle … let me tell you, it’s scary enough standing still and doing it.”

“I don’t want any part of it,” Jeff informed Adam. “And you are not using my Jeep.”

As Adam and his friends walked out to the school parking lot following the end-of-year athletic banquet, Adam announced he was ready for the bridge. Jeff remained steadfast in his refusal to allow Adam to jump from his car, and Richard, who was driving a Pontiac Grand Am, didn’t have the right type of vehicle. Another friend volunteered his Suzuki Samurai, and they headed out into the night, a convoy of a half-dozen vehicles with Adam riding in the back of the open-topped Samurai.

Richard drove directly behind the Samurai, nervous but also confident that nothing would happen to Adam. “He’d bend, he’d get hurt,” says Richard, “but he never broke. He never didn’t get up.”

The convoy slowed to about thirty miles per hour halfway across the bridge. The water below was dark, making it impossible to spot any boats or floating debris—not that Adam cared. Richard watched the Samurai edge closer and thought, Maybe this isn’t such a good idea. The Samurai was now in the bike lane, just a foot or so away from the waist-high concrete wall. Then the silhouette of Adam rose up in the back, held on to the roll bar for a second, and dived into the abyss.

Richard threw on his hazard lights and screeched to a halt as Jeff sped past to get to the other side, where Adam would exit the water. The other cars pulled over as well, and Adam’s buddies scrambled out and leaned against the bridge wall, scanning below. There was just enough ambient light for Richard to see Adam swimming to shore.

“You all right, Adam?” he shouted.

“Yeah!” Adam yelled up.

Sprinting down the trail, Jeff reached the water’s edge the same time Adam did. “Damn, Adam,” he said, offering a hand. “How was it?”

Adam explained that when he’d dived out of the Samurai, he had hoped to straighten out and land feet first. Instead, he’d hit the water sideways, which from that height and with the forward momentum was more than he’d bargained for.

“I don’t think I’ll do that again,” was his response. “Slapped the water pretty hard, but I’m glad I did it—it would have eaten at me forever.”