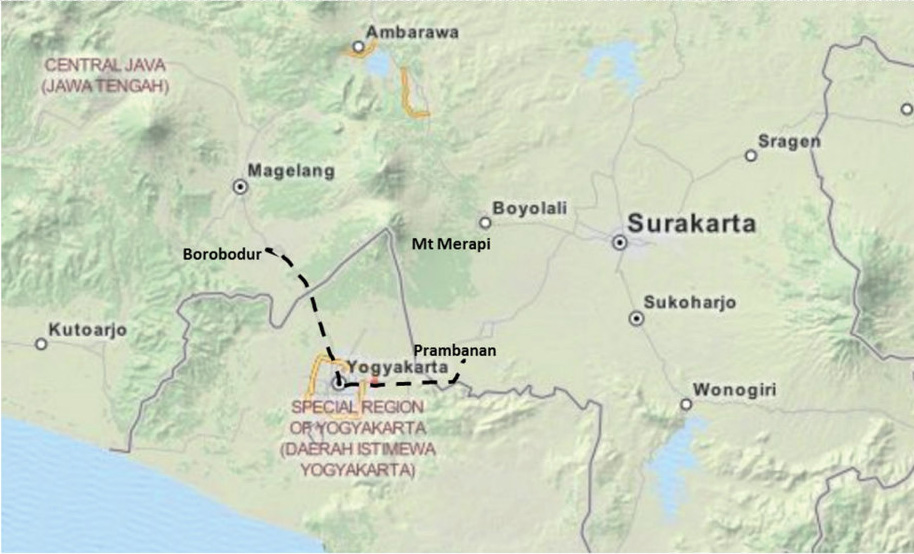

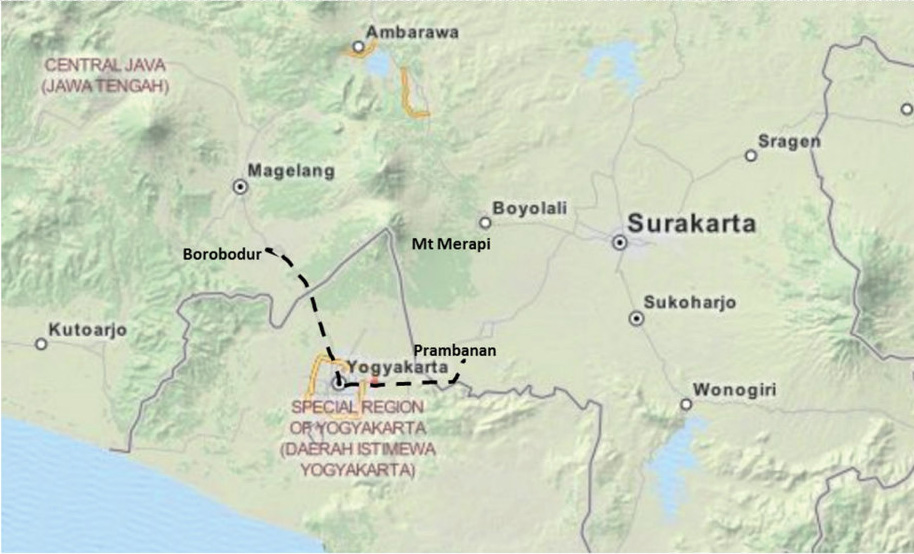

Map of Yogyakarta Region

4 Central Java – The Greatest Monument in the World?

Map of Yogyakarta Region

The advantage of travelling by train is that you always arrive in the city centre and there is always a hotel across the street from the station. After arriving in Yogyakarta I quickly find an Indonesian style hotel, throw my stuff in the corner and set out to explore this classical Javanese city that is always called Yogya. I and thousands of others find the nearby Jalan Malioboro which is a bargain shopper’s dream. Store after store of stuff, always cheap and always on sale. At the far end of this street is the old Dutch fortification, Fort Vredeburg, which is now a military history museum. The fort looks imposing from the outside and apparently has some interesting dioramas which tell the story of the Indonesian independence struggle against the Dutch, but it is late in the day and the museum is about to close. Like many visitors to Indonesia the next morning I am reminded that I am in a Muslim country by the early morning call to prayer (4 am) from the nearby mosque. Yogya is a centre for education, culture, the arts, the batik industry, all sorts of handicrafts and food. Food vendors and market stalls line the streets selling local dishes and finger foods. Mobile kitchens serve bakso meatball soup, steamed bakpau buns filled with a sweet bean paste and sate sticks of meat are grilling in clouds of smoke and aroma. I pass a fruit stand displaying all the colours of the tropics – purple mangosteens, clusters of furry red rambutans, a pile of juicy green mangoes, bunches of yellow bananas, boxes of oranges and green apples. As well as the king of tropical fruits, the spiky durian, which if you can get by the smell makes for delicious eating. Our archipelago traveller, Alfred Russel Wallace, provides the best description of this unique fruit:

The five cells are silky-white within, and are filled with a mass of firm, cream-coloured pulp, containing about three seeds each. This pulp is the edible part, and its consistence and flavour are indescribable. A rich custard highly flavoured with almonds gives the best general idea of it, but there are occasional wafts of flavour that call to mind cream-cheese, onion-sauce, sherry-wine, and other incongruous dishes. Then there is a rich glutinous smoothness in the pulp which nothing else possesses, but which adds to its delicacy. It is neither acid nor sweet nor juicy; yet it wants neither of these qualities, for it is in itself perfect. It produces no nausea or other bad effect, and the more you eat of it the less you feel inclined to stop. In fact, to eat Durians is a new sensation worth a voyage to the East to experience … as producing a food of the most exquisite flavour it is unsurpassed.

Unsurpassed, but I decide to pass on the durian and stop at a local warung or eating house to try a traditional dish from Central Java. Gudeg is made from young unripe jackfruit boiled for several hours with palm sugar and coconut milk. This is usually accompanied by opor ayam, which is chicken simmered in coconut milk. I find the Gudeg is a bit too soft and sweet for my taste but the chicken is delicious.

Yogyakarta lies within the heartland of Javanese culture, between the active volcano of Mount Merapi to the north and the pounding surf of the Indian Ocean to the south. The area has been the centre of the ancient Mataram kingdom (eighth to tenth centuries), the second Mataram kingdom (seventeenth to eighteenth centuries) and then the Sultanate of Yogyakarta until today. The province has had a special status since the time of the Indonesian war of independence, when Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX offered the fledgling Indonesian government his enclave as a capital city. Thus Yogyakarta became the revolutionary capital of the Republic of Indonesia from 1946 to 1949 when Batavia was still occupied by the Dutch.

In the eighth century Srivijaya extended its influence from South Sumatra to the plains of Central Java through the Buddhist Sailendra Dynasty. The reign of these Sailendra Kings was marked by the construction of the greatest monument in the world – Borobudur. Not a temple in the strict sense of the word since it has no interior, Borobudur is built around a hill on the plains of Central Java surrounded by green terraced rice fields and 3000 metre volcanic peaks such as Mount Merapi and Mount Merbabu. The Sailendra Dynasty gained wealth and power through a flourishing sea trade with India which must have brought cultural contact with the Pala Dynasty of Bihar and Bengal, as the inscriptions and visual imagery on Borobudur share the same faith and artistic style. The architect of this place of worship, that nameless master builder, had an incredible vision. The monument is planned to the last detail and on a scale that has never been attempted anywhere else in the world. It is certainly the greatest Buddhist monument in the world and there is nothing like it in India or anywhere else.

A stone inscription written in Sanskrit and found in the nearby village of Kalasan may refer to the building of Borobudur:

In the flourishing kingdom of the Raja, which is the ornament of the Sailendra Dynasty, a temple to Tara [a feminine Bodhisattva] has been built by the guru of the King of the Sailendra Dynasty. It is after seven centuries of the Shaka era [779 AD] that the Raja built Tara’s temple to honour the guru … This incredible donation in lands given to the community by the Royal Lion will be maintained by all the Kings of the Sailendra Dynasty.

Borobudur was built to resemble a microcosm of the universe and its purpose was to provide a visual image of the teachings of the Buddha and to show in a practical manner the steps through life that each person must follow to achieve enlightenment. Constructed from over one million blocks of stone, the monument takes the form of a stepped pyramid consisting of a base and four terraces above that lined with 1460 carved stone panels illustrating Buddhist scriptures. Pilgrims would be led by a guide who could explain the stories and messages carved in the stone. By circling each successive terrace in a clockwise direction, the dedicated pilgrim could hope to physically and spiritually reach a level of enlightenment reflected by the stone Buddhas housed within their bell-shaped stupas on three concentric circles at the highest level of the monument. The name Borobudur is thought to be derived from the Sanskrit words meaning ‘the mountain of the accumulation of virtue on the ten stages of becoming a Bodhisattva’. For those interested in numerology there are 104 Buddhas in the first gallery, 104 in the second, 88 in the third, 72 in the fourth and 64 in the fifth. The original total of 504 Buddhas is believed to have significance.

It was Sir Stamford Raffles who receives credit for ‘rediscovering’ Borobudur during the period of British rule in Java from 1811 to 1816 and information about this monumental work of art came as a great surprise to the outside world. After being cleared of the jungle that had hidden its secrets for centuries, Raffles writes in The History of Java of his experience when first viewing the Borobudur:

No description in writing can convey the amount of work that has gone into this immense monument and the detail of its story carved in stone. Its grandeur is too vast and overwhelming, and it compares to no other monument in the world … The amount of human labour and skill expended on the Great Pyramids of Egypt sinks into insignificance when compared to that required to complete this sculptured hill temple in the interior of Java.

I agree with Sir Stamford Raffles that Borobudur is the greatest monument in the world and I am astounded that an internet search will list the pyramids amongst the top ten historic monuments and yet not include Borobudur. There is even a recent television documentary entitled Seven Wonders of the Buddhist World that does not include the Borobudur monument.

Pilgrims would approach Borobudur from the east and it is thought that before visiting the temple they first paid homage to the three huge stone statues enshrined at the nearby Candi Mendut. This temple lay almost completely buried and hidden by a mound of ash, earth and shrubs for a millennium until 1836 when the Dutch began clearing the ground for a coffee plantation. For this reason its statues were found completely intact. On the left side of the entrance to the inner sanctum is a wall carving showing Hariti, who was once a child-eating demon, but after her conversion to Buddhism she is depicted as a loving mother surrounded by children. On the right side of the entrance is a wall carving of Atavka, who was once a flesh-eating ogre, and is now sitting on pots of riches and surrounded by happy children. In its sanctum, facing east and lit by the morning sun sits the 1200-year-old Buddha. Carved from a single stone monolith he is seated on a simple throne with his feet resting on lotus petals. He wears no special garments or vestments and is naked except for a loincloth. The noble head has its eyes lowered in contemplation and on either side of the Buddha and facing each other are two Bodhisattvas, Lokesvara and Vajrapani. These three statues, the noblest representation of Buddhist figures in Central Java, fill almost the entire space of the brick inner sanctum of the temple. I can sense the atmosphere of peace and devotion within this space, and outside a line has already formed of pilgrims from Northern Asia who have come here to burn incense sticks, place offerings and pray in the inner sanctum of Candi Mendut.

During the full moon in May of each year thousands of Buddhists observe Waisak or Vasak Day, which celebrates the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and death, by performing an annual ritual which begins at Candi Mendut and is followed by a procession which leaves there at mid-afternoon and proceeds along a four kilometre route to Borobudur. Here the crowds gather during the evening and as the full moon rises, candles are lit and flowers are strewn about as offerings, followed by prayer and chanting.

I take advantage of the cool morning air and the clear morning light to begin my spiritual journey around the ancient terraces of the Borobudur monument. The pilgrim to the shrine would have been first led around the base of the temple and shown the friezes which illustrate the consequences of living in the World of Desire. In this realm ruled by Greed, Envy, and Ignorance, man is a slave to earthly desires and suffers from the illusions that are caused by these unfulfilled yearnings. I enter the monument from the eastern stairs and follow the square terraces in the prescribed clockwise direction and always ascending to the next level from the eastern stairs. The life of the Buddha (Prince Siddharta Gautama) lies on the walls before me, as he grows, marries and leaves his father’s palace, is moved by the misery of the lowly and lost, and gathers knowledge until encompassing all wisdom. The circumambulation of the four terraces is five kilometres in length and as the pilgrims gradually climb the pyramid they view 1300 carved panels showing how to conquer desire and attachment, by viewing the life of the Buddha and his previous incarnations. This is the World of Form and corresponds to the earthly realm in Buddhist symbology, until Prince Siddhartha, having at last obtained Nirvana, bathes in the river Niranjana. Here, his trials and temptations are over – he is the Buddha, the noble purified soul. On the highest and now circular terraces the sculptured panels are replaced by great stone cupolas through which the forms of the Dhyani Buddhas are only partly visible. Finally, at the highest point the pilgrim reaches the symbolic Kailasa or centre of the cosmos, where the Gautama Buddha is believed to sit inside the masonry of the large cupola at the summit of the monument, invisible except to the most devout of pilgrims.

The next morning I hope to reach some level of spiritual enlightenment by joining a dozen other dedicated pilgrims at 4 am to experience the sunrise from the top of Borobudur. The night is black and silent as we enter the great monument and the moonlight casts mystical shadows around the temple. Protecting us from these shadows our torches light the way as we climb directly up the stairs that lead to the top of the monument. I stop to rest at one of the carved gateways that lead from one level to the next and my torch reveals above the gateway the fearsome features of a Kala Head. In Javanese mythology Batara Kala is the god of death or destruction and I remember this warning as I climb to the upper terraces.

Knowing that the sun has risen over Borobudur for more than a thousand years is awe-inspiring. I assume the same position as the seventy-two Buddhas on the uppermost terraces, legs crossed, hands posed, waiting in silent contemplation for the dawning of the new day. Slowly, very slowly, the black of the night is replaced by a deep blue light. I have never experienced this light before and it seems to last for a long time before slowly changing to a sky blue and then an early morning grey daylight. Soon the red disc of the sun appears revealing the blue profiles of the surrounding volcanoes, the blue grey of the distant hills, the dark green of the forests high on the hillsides, the bright green of the terraced rice fields, and the white morning mist that fills the lowest parts of the valleys.

Later I descend to the lower terraces to take advantage of the clear morning light and photograph the carved image of what is known as the ‘Borobudur Ship’, representing the ships of the Sailendra Dynasty that would have sailed to India bringing gold, spices, sandalwood and other trade goods from Indonesia. I then climb to a mid-level terrace to photograph one of the many images showing the burning of incense as an offering to the gods. For our ancestors the smoke from incense made of resins, woods, bark and aromatic plants had magical properties and their perfumed scents were sent heavenward to honour the gods. For the Indians, both Hindu and Buddhist, sandalwood from the eastern islands of the archipelago is the most favoured perfume to be burnt as incense.

I return to my simple hotel for a meal, an afternoon nap, and when I awake it is time for the afternoon bath. I have referred to the cult of bathing in Java and it is one of the most important parts of the daily ritual. The villages of Java are never far from the sound of running water; however, if you are not close to a village stream then the delight of these traditional hotels is the Indonesian bak mandi. This is a small tiled tub in the bathroom that is filled with water which, for a reasons I cannot explain, is always deliciously cool. After a day of working, travelling or exploring ancient temples there is nothing better than to grasp the dipper provided and splash this cold water over a hot, tired body. The first splash of cold water on your skin is a jolt to the system and there is no sensation that compares to it. Next raise the dipper higher and let the cool water trickle over your head and run down your back. It is so refreshing that this splashing, soaping, washing, rinsing, and shampooing can last for an hour. The next delight is for me to then sit outside on the small terrace with a large bottle of cold beer and watch the world go by, while contemplating life and the distant mountains. Following the victory of the Sanjaya King over his Sailendra brother-in-law, Hinduism recovered its precedence in Central Java and the new overlords began building temples designed to consolidate their power and celebrate the resurgence of the Hindu religion. Shiva became the main object of worship, because as the God of destruction and creation he is the most powerful of the Hindu gods. Characteristics needed by new rulers seeking to establish and then protect their kingdoms.

The Prambanan Temples

A stone inscription describing the inauguration of a Shiva temple by King Lokapala dated to 856 describes the temple as ‘ a beautiful dwelling for the gods’ and is believed to refer to the construction of the greatest Hindu temple complex outside India, the Prambanan. Sir Stamford Raffles credits the discovery of Prambanan to a Dutch engineer who in 1797 was sent to survey the location of a fort to be built between Yogyakarta and Solo. In 1812 Raffles sent Colonel Colin McKenzie to make an accurate survey of the ruins. Having served in India, McKenzie tells of his surprise at finding statues of Hindu gods on an island whose inhabitants are Muslim. Raffles describes his visit to Prambanan soon after it was first cleared from the jungle:

The Goddess Durga, known by the Javanese as Loro Jonggrang

Nothing can exceed the air of desolation which this spot presents; and the feelings of every visitor are attuned, by the scene of surrounding devastation, to reflect, that while these noble monuments of the ancient splendour of religion and the arts are submitting with sullen slowness, to the destructive hand of time and nature, the art which raised them has perished before them and the faith which they were to honour has now no other honour in this land.

I arrive at Prambanan as soon as it opens, to avoid the tourist buses. The temple complex is aligned to the points of the compass and has the form of a raised terrace surrounded by a massive square wall. Inside this first wall are the bases of what were 224 small shrines, neatly arranged in four descending tiers and some of which have been reconstructed. Inside the second wall is the towering spire of the central Shiva temple which replicates Mount Meru, the sacred mountain of the Hindu cosmos. It is flanked by subsidiary temples to Brahma and Vishnu, bringing these two major streams of religious practice within the orbit of the worship of Shiva. The statue of Shiva is now missing from the inner sanctum of his temple, but in the surrounding rooms are the statues of Agastya (the god of wisdom) on his right, his son Ganesha (the god of success) is behind him, and on his left is the goddess Durgha whom the Javanese refer to as Loro Jonggrang (the exalted virgin).

Lining the inside of the balcony balustrade of the Shiva temple are seventy-two stone relief panels which portray the Ramayana epic. These tell the popular story of Rama and Shinta: a disconsolate Rama is shown searching for his stolen wife Shinta until Hanoman, the king of the monkeys, leads him to her. This visual storytelling is shown in the dance-like postures that Rama and Shinta assume as the story unfolds. Despite the Islamization of Java, the traditions of the great Indian epics of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata have stayed alive in the repertoire of the wayang kulit shadow plays and the dance dramas of modern Indonesia.

The giant Raksasas guarding the entrance to Candi Sewu with Mount Merapi in the background

It is a long walk north from Prambanan to the eighth-century temple of Candi Sewu, which is the second largest Buddhist temple complex in Central Java after Borobudur. Although there are only 249 temples, the name in Javanese translates to ‘a thousand temples’. The Javanese legend of Loro Jonggrang begins when Prince Bandung Bandawasa falls in love with her. She is the daughter of King and Queen Bako whose kingdom was conquered by the Bandawasas and who have killed her father. The Prince wishes to marry Loro Jonggrang and as a way of saying no she requests the conqueror to prove his powers by building one thousand temples within a single night. Calling on help from the spirits, Prince Bandawasa and his demons seem to be just moments away from accomplishing this task when, alarmed by his progress, Princess Jonggrang asks the village women to pound their wooden rice mortars with their pestles, a sound mistaken by the roosters as the new dawn. Upon hearing the roosters crow and fearing that the sun is about to rise, Bandawasa’s demon helpers flee. Before this false dawn Prince Bandawasa has already created 999 temples. In anger at his failure to be able to marry Loro Jonggrang he applies a curse on the Princess which turns her into a stone. Is Candi Sewu the site of the temples built by Prince Bandawasa as part of his condition to marry Loro Jonggrang? Is the statue of the Indian goddess Durga in the Prambanan temple the embodiment of the beautiful princess?

Full Moon over the Prambanan Temples

For a thousand years the giant stone guardians of Candi Sewu, the Raksasas, have stood either side of its four gates facing the points of the compass. With a kris in their waist-band, a club in their right hand and a snake in their left hand, they stand ready to protect the ancient temple from those with malevolent intent. Sir Stamford Raffles describes the stone guardians after the temples were recovered from the jungle:

In the course of my life I have never met with such stupendous and finished specimens of human labour, and of the science and taste of ‘ages long since forgot’ crowded together in so small a compass … Having had in view all the way one lofty pyramid or conical ruin, covered in foliage and surrounded by much smaller ones, in every stage of humbled majesty and decay, you find yourself on reaching the southern face, very suddenly between two gigantic figures in a kneeling posture, and of terrific forms, appearing to threaten you with their uplifted clubs.

After a day exploring the temple complex I return in the evening to see the dance drama performed by the Ramayana Ballet featuring musicians from a gamelan (gong) orchestra and dozens of dancers. Before the performance I pause to enjoy a cool drink on the terrace overlooking Prambanan. The music in the background is the gamelan music of Java, the rhythmic bell-like sound played on numerous brass gongs and xylophones. Gamelan is Java – the soul of Java – and its haunting exotic sound is compared to the sound of a flowing stream. The heat of the day is finally switched off and a faint breeze mingles the musky odour of the earth with the evening scent of the jasmine flower. Night comes quickly in the tropics and as the sky darkens I watch in amazement as a full moon appears over the holy temples of Prambanan. The gentle sound of the gamelan, the scents of the earth, and the full moon shining over these ancient temples combine to create the most perfect moment.

The dance drama begins when Rama and Shinta dance with romantic adoration of each other against the majestic portal of the palace. They are not ordinary mortals but gods, Rama is the avatar of the Hindu supreme-god Vishnu, Shinta is the avatar of the goddess Lakshmi and is portrayed as the epitome of female beauty and purity. She follows her husband into exile and the pair enter the Dandaka forest where they are soon spotted by a minister of the demonic King Rahwana. He wants to kidnap beautiful Shinta. Soon the minister Maricha transforms himself into a golden deer. Shinta would love to have such a cute deer so Rama leaves her in the care of his brother Laksamana and leaves to capture the deer. When an arrow hits the golden deer it becomes Maricha again and screams for help (with the tragic sounds of the music). Shinta believes that her dear Rama is in some trouble, so she sends Laksamana to the rescue. Laksamana wisely draws a magic circle around her for protection and runs to the forest. But crafty Rahwana is just waiting for this moment. Now disguised as a poor old priest, he begs Sita for water, which kind-hearted Shinta offers him. Just then he turns back into his own demonic form and snatches Shinta out from the protective circle.

Rahwana carries Shinta away to his kingdom. But the giant bird Jatayu attacks the kidnapper to rescue Shinta. After a short fight the bird is mortally wounded. Rama and Laksamana discover Jatayu just before he draws his last breath and learn of her fate. Just in time the white monkey general Hanoman appears on the busy stage. Fearless Hanoman sneaks into Rahwana’s kingdom to tell Shinta that help is on the way. For proof he gives her Rama’s ring. And it’s not a moment too soon, because just then the demon Rahwana tries to force Shinta into marriage. By this time the gamelan music is reaching a crescendo because the final battle is under way. Hanoman storms the palace with his monkey troops and the ugly warriors of King Rahwana are defeated. Shinta, beautiful as ever, is reunited with her husband Rama.

An inscription dated to 1016 refers to an enormous eruption of Mount Merapi. A giant cataclysm shook Central Java to its foundations as its volcanoes erupted, killing people by the thousands and burying its temples under layers of volcanic ash. These temples were abandoned, and over centuries nature reclaimed these monuments as trees, shrubs and vines covered the ancient terraces, hiding them from view. The Javanese, later converted to Islam, avoided these ancient sites which they believed represented supernatural forces and were haunted by powerful spirits, allowing these magnificent temples and monuments to be lost in the luxuriant vegetation of the island. From this time there was a period of relative silence until the next great political and cultural resurgence which occurred in East Java.