George Metesky

Mug shot

Linkage analysis was anything but a formal procedure at this time for law enforcement. There was no Behavioral Science Unit yet at the FBI, and cops had to figure it out on their own. Often, they had little experience with multiple homicides. Nevertheless, a psychiatrist in New York was making inroads for the future. In 1956, the same year the police in Prince George’s and Ann Arundel Counties thought the murders of five young women were related, three frustrated N.Y.P.D. investigators visited Dr. James Brussel in his Greenwich Village office.

More than three dozen explosions had occurred in Manhattan between 1940 and 1956, in public places such as Radio City Music Hall and Grand Central Station. The perpetrator, known as the “Mad Bomber,” had also sent a barrage of angry letters to area newspapers, politicians, and a utilities company, Consolidated Edison. The stymied investigators showed Brussel everything they had.

Looking for a method to the Bomber’s madness, Brussel studied the crime-related material, especially the letters, and provided details: Because the first letter had been sent to Consolidated Edison, he surmised that the offender was a former employee with a grudge. Because bombs were the weapons of choice, he thought the perpetrator was most likely a male European immigrant, which also revealed his religion: Roman Catholic. The “Bomber’s” progressively more paranoid messages placed his age between 40 and 50 and suggested he was a fastidious loner.

Brussel added that this man probably lived with an older female—a mother figure—who took care of his basic needs. Because the letters were often mailed in Westchester County, if one considered this place to be halfway between his home and his target (just a guess), he probably resided in an ethnic community not far from the city. There were several options.

Brussel also suggested that police use a specific strategy: Publish the profile in the newspapers, because an angry man like this would surely react. The Bomber wanted people to see how important he was. That impression was the gist of his pompous letters.

Eventually, this strategy paid off. The perpetrator did respond, pointing out errors and revealing the date of the incident that had so angered him. With this information, it was possible for Consolidated Edison to check through employee records. Early in 1957, a clerk matched unique phrases the Bomber had used to phrases in written complaints to the company.

When the police finally arrested George Metesky, age 54, in Waterbury, Connecticut, the profile proved to be correct on many points.

George Metesky

Mug shot

An FBI special agent, Howard Teten, was intrigued. He incorporated some things from Brussel’s approach into his own attempt to read behavior at crime scenes. With this, Teten would eventually set up the Behavioral Science Unit and initiate the FBI’s version of profiling. But that was over a decade away.

Although such a sophisticated analysis was not available to the detectives in Maryland during the late 1950s, they believed that the crimes they were seeing against women in these loosely related locations suggested a single offender.

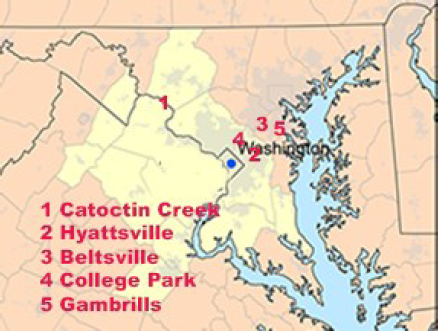

At that time, Hyattsville, Beltsville, Gambrills, College Park, and Loudoun County were all less than an hour’s drive from one another. It wasn’t far-fetched to envision a predator scouting back roads in this area for victims. Rees, they knew, was a wanderer. He traveled to many different towns to perform.

MSA Map by Kmusser

However, investigators discovered that Rees no longer lived in Hyattsville with his parents. As a musician, he was on the road quite often, and the Reeses weren’t sure how to reach him. Sometimes he just showed up at their place, but he rarely let them know where he was.

The jazz musician remained a suspect.