Chapter 17

(Almost) Ten Myths about Studying Kabbalah

In This Chapter

Debunking so-called prerequisites for Kabbalah study

Debunking so-called prerequisites for Kabbalah study

Revealing the truth behind Kabbalah products

Revealing the truth behind Kabbalah products

Clarifying what Kabbalah is and isn’t

Clarifying what Kabbalah is and isn’t

Kabbalah has been and probably always will be surrounded by myths. A number of the myths about Kabbalah concern themselves with restricting the study of Kabbalah to certain individuals and excluding others from its study. Other popular myths about Kabbalah have to do with the commercialization of Kabbalah in recent years as well as simply what Kabbalah is and what it isn’t. This chapter lets me play myth-buster and set you straight on the top ten myths about Kabbalah.

You Have to Be a Man

Anybody who examines the traditional Jewish texts that have been central to Kabbalah for centuries can see that men and women are viewed through different lenses. Traditional religious responsibilities, restrictions, and customs reflect many different roles for men and women in the family as well as in ritual life.

But ultimately, Kabbalah is just as available to women as to men. I only have to look to my own family experience for proof of this point. I have a son and two daughters; both of my daughters graduated from Jewish high schools and have shared with me repeatedly that Kabbalistic ideas were regularly taught in their schools. Over the years, I’ve heard the stories, customs, lessons, and insights grown out of Kabbalistic tradition that were shared with them by their teachers and rabbis. And I’m not just referring to an occasional tidbit of Kabbalah here and there. Jewish education for girls is taken quite seriously. I can have in-depth, high-level theological discussions with both of my daughters (and we’ve been having them since they were in middle school!).

The bottom line is that you don’t have to be a man to study Kabbalah. I’ve. studied Kabbalah with authentic Jewish teachers who teach Kabbalah to both women and men all the time.

You Have to Be Married

Marriage is an important institution in Kabbalistic tradition, and the sanctity of marriage is a given for the Kabbalist. Getting married is considered both a social and a spiritual achievement. A person’s status rises upon marriage because the Kabbalist believes that each person has half a soul and needs to find and connect with the other half to achieve a certain level of wholeness. The person who’s privileged to receive such a high level of wholeness has something of an exalted status for the Kabbalist, but marriage isn’t a prerequisite for Kabbalah study.

You may be wondering why someone would even suggest that one has to be married in order to study Kabbalah. One reason is because Kabbalah does, in fact, require a certain level of maturity, and marriage usually imparts some maturity because of the wholeness it creates.

One doesn’t have to be married to study Kabbalah, but the more mature, stable, and experienced a person is, the better able he or she is to explore the most profound notions about the meaning of life and death, good and evil, and pain and suffering. The question of whether a student should wait to study Kabbalah until he or she is mature enough has long been a concern in Kabbalistic tradition. It would be foolish to attempt the study of a difficult subject without the proper prerequisites, but what does it take to be a mature student who is ready to study Kabbalah?

Knowledge of the ten sefirot (see Chapter 4)

Knowledge of the ten sefirot (see Chapter 4)

Basic knowledge of the stories in the Torah: For example, knowledge of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and their wives Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, is essential. These seven people are major characters in stories that Kabbalists study and refer to on a regular basis.

Basic knowledge of the stories in the Torah: For example, knowledge of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and their wives Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, is essential. These seven people are major characters in stories that Kabbalists study and refer to on a regular basis.

Being rooted in both law as well as ideas (or concepts): For the Kabbalist, the study of Kabbalah is never only theoretical. An important distinction that many scholars have noted about the difference between Kabbalah and other forms of mysticism is that Kabbalah isn’t just a discussion of ideas; instead, it’s a constant effort to connect those ideas to this world. From ritual acts to social behavior, everything a Kabbalist does is rooted in an ancient tradition that’s constantly looking for ways to express itself in life. The giving of charity, acts of kindness, child-rearing, traditional celebration of the Sabbath and holidays, observance of ritual law in all realms (including eating, sleeping, and sexual behavior), and relations in the marketplace are all governed by the individual’s participation in the ancient process making an effort to remain conscious and to connect every breath, action, and thought to the Infinite One. A Kabbalist needs to be rooted in the knowledge and practice of Jewish law as a perquisite to the exploration of esoteric and transcendent ideas or concepts.

Being rooted in both law as well as ideas (or concepts): For the Kabbalist, the study of Kabbalah is never only theoretical. An important distinction that many scholars have noted about the difference between Kabbalah and other forms of mysticism is that Kabbalah isn’t just a discussion of ideas; instead, it’s a constant effort to connect those ideas to this world. From ritual acts to social behavior, everything a Kabbalist does is rooted in an ancient tradition that’s constantly looking for ways to express itself in life. The giving of charity, acts of kindness, child-rearing, traditional celebration of the Sabbath and holidays, observance of ritual law in all realms (including eating, sleeping, and sexual behavior), and relations in the marketplace are all governed by the individual’s participation in the ancient process making an effort to remain conscious and to connect every breath, action, and thought to the Infinite One. A Kabbalist needs to be rooted in the knowledge and practice of Jewish law as a perquisite to the exploration of esoteric and transcendent ideas or concepts.

Dedication: Kabbalah isn’t a fad or a hobby. It isn’t a self-help craze or a cult. And it isn’t some far-out superstition. Kabbalah requires seriousness, commitment, perseverance, kindness, and endurance. Just as one doesn’t dabble as a brain surgeon, Kabbalists must dedicate time, knowledge, and commitment to master the art and science of Kabbalah.

Dedication: Kabbalah isn’t a fad or a hobby. It isn’t a self-help craze or a cult. And it isn’t some far-out superstition. Kabbalah requires seriousness, commitment, perseverance, kindness, and endurance. Just as one doesn’t dabble as a brain surgeon, Kabbalists must dedicate time, knowledge, and commitment to master the art and science of Kabbalah.

Can someone pick up a book of Kabbalah and randomly stumble upon an insight or piece of wisdom of value? Yes, of course. But unless that person commits to Kabbalah, he or she can’t in honesty claim to be a Kabbalist. Basically, it just isn’t possible to dabble in Kabbalah.

Working with a teacher: Kabbalah is largely an oral tradition passed on from one generation to the next. The Kabbalistic texts often aren’t clear enough to be meaningful unless the person studying them is aided by the commentary of a living Kabbalist. Kabbalistic wisdom doesn’t apply in the same way to every person, so a student needs the insight of a teacher to get the most out of his or her study.

Working with a teacher: Kabbalah is largely an oral tradition passed on from one generation to the next. The Kabbalistic texts often aren’t clear enough to be meaningful unless the person studying them is aided by the commentary of a living Kabbalist. Kabbalistic wisdom doesn’t apply in the same way to every person, so a student needs the insight of a teacher to get the most out of his or her study.

Certainly one can find a lot of information in books, and many of the growing number of books on Kabbalah are profoundly insightful and informative. In fact, I’ve been studying five such books on a constant basis for many years. I truly believe that I’ve learned much from my own study in solitude with these great volumes of Kabbalah in English, but nothing matches an encounter with a contemporary teacher who can offer his or her special guidance or blessings in a way that a book never can.

You Have to Be an Orthodox Jew

This myth is rooted in the reasonable idea of prerequisites. As with many of the other myths in this chapter, the trend in Kabbalistic history is to require that the serious student be rooted in tradition, experienced with the broad range of traditional practices, and mature and knowledgeable enough to grasp and creatively participate in discussions of basic and complex ideas. But being an Orthodox Jew doesn’t guarantee any of these skills or abilities.

The rigors of Orthodox life require a great deal of knowledge and ongoing study, both of which are important prerequisites for the serious student. But one easily can be an Orthodox Jew without understanding and insight, just as one can be far from the tradition of Orthodoxy and yet have the personality traits and the talents to both study and teach Kabbalah.

You Have to at Least Be Jewish

Make no mistake about it: Kabbalah is the theology of the Jewish people and has been seen and accepted as such for at least the last 500 years. Its symbols, values, customs, and history are all part of the Jewish experience. The great Kabbalists were all practicing traditional Jews, and each held encyclopedic knowledge of Jewish tradition. Their behavior reflected that tradition.

Throughout history, people have made attempts to mix Kabbalistic ideas with other approaches and philosophies and call these efforts Kabbalah. For example, a Christian Kabbalah that borrowed freely from the Kabbalistic tradition of the Jewish people emerged as recently as the last few centuries in Kabbalistic history. Best described as watered-down Kabbalah, Christian Kabbalah certainly never retains authentic Kabbalah’s fundamental requirement of being rooted in ritual law and traditional religious behavior.

.jpg)

However, there’s a profound difference between the way a Jewish person relates to Kabbalah and the way a person who isn’t Jewish relates to it. Traditional Kabbalistic belief places a heavy burden on the Jewish people; the tradition doesn’t require the same of someone who isn’t Jewish. The more a Jewish person reads, learns, and understands the obligations imposed upon Jews by the tradition, the more his or her obligation grows.

According to biblical tradition, the Jewish people are to view themselves as “a nation of priests.” This notion is often referred to in shorthand as “the chosen people.” From the outside, the notion of the chosen people seems strange until one realizes that the term “chosen” doesn’t mean greater status but rather greater responsibility for learning and performing the divine commandments. As priests in the world, the Jewish people relate to everything as sacred. So although you don’t have to be Jewish to study Kabbalah, for a Jewish person, studying Kabbalah is learning the way the Jewish family has sought to understand God for many centuries.

You Have to Be Over 40

One can trace a tendency throughout Kabbalistic history to put off the study of Kabbalah until after a student masters the basics of Jewish learning and tradition. Kabbalists often refer to the following passage (Ethics of the Fathers 5:24) in the Mishnah (see Chapter 13):

At five years (the age is reached for the study of the) Scripture, at ten for (the study of) the Mishnah, at thirteen for (the fulfillment of) the commandments, at fifteen for (the study of) the Talmud, at eighteen for marriage, at twenty for seeking (a livelihood), at thirty for (entering into one’s full) strength, at forty for understanding, at fifty for counsel, at sixty (a man attains) old age, at seventy the hoary head, at eighty (the gift of special) strength, at ninety (he bends beneath) the weight of years, at a hundred he is as if he were already dead and had passed away from the world.

Many books about Kabbalah refer to a requirement that a student of Kabbalah needs to be over 40, but no such absolute age requirement exists. Some of the great sages in Jewish history mastered Kabbalah at a young age, whereas others never felt ready to enter into its study. The greatest Kabbalist who ever lived, Rabbi Isaac Luria (known as the Ari), died at the age of 39. He never even reached the age of 40.

Even though there’s no age requirement for Kabbalah students, Kabbalistic tradition is much more welcoming to the student who has done the proper preparation in order to enter the spiritual realms of Kabbalah.

You Have to Buy Expensive Books in Hebrew

Over the past several years, I’ve been asked many times whether I think that there’s any truth to the notion being perpetuated by a major merchandiser of new-age Kabbalah that merely having a Hebrew set of the multivolume holy work, the Zohar, in one’s home will bring good fortune.

I’m a book person. I have over 3,000 books in my home collection, I’ve been involved with Jewish book publishing for over 25 years, and I’ve served as a librarian in addition to authoring several books. The presence of the books that surround me in my home, both those that I’ve read and those that I haven’t, unquestionably enhance my life. As one of my teachers put it, “Just the title of a book and the aesthetics of its design are sometimes enough to have great impact on a room and its inhabitants.”

The presence of a holy book in the home has a positive influence on its residents, but Kabbalah students aren’t required to stock their shelves with expensive sets of Hebrew books. And purchasing such books if one can’t afford them is certainly out of order. No amount of potential good luck can justify putting oneself in financial jeopardy by buying books or anything else. Kabbalists throughout the centuries have studied the legal area of law that deals with protecting oneself and not putting oneself in jeopardy — physically, emotionally, or economically. Kabbalists often rely on the libraries of local Jewish study houses to supplement their holdings, so that, ultimately, they own some and share some.

That said, one of my Kabbalah teachers said, “Simply to bring a few great Jewish books into one’s living room, even without opening them, may very well do some good.” And Kabbalists do believe in the power of the Hebrew letter, merely as it sits on a page. It’s a time-honored belief among Kabbalists that if one merely passes her eye over certain passages in Hebrew or Aramaic, she can receive the text’s blessings. Similarly, anyone who has ever been privileged to be in a synagogue and close to an open Torah (especially someone who’s asked to read from the Torah or offer a blessing at the reading of the Torah) knows the awesome look of the Torah scroll. One need not know a letter of the Hebrew alphabet or a word in its vocabulary in order to feel the power of the Hebrew Torah scroll.

You Have to Follow a Dress Code

If you were able to look at portraits of each of the leading Kabbalists throughout history, you would notice that they were all male and all had beards and wore head coverings. In the world of Hasidism today, where the study of Kabbalah is alive and well, beards are common, and men study while wearing a hat or scull cap.

Does this mean that if you’re a man you have to follow suit? I’d say no. Growing a beard certainly isn’t a requirement for Kabbalah study.

As far as head coverings go, in Jewish tradition, wearing a head covering is a reminder of God’s presence. Some men even wear two head coverings at the same time (a skull cap covered by a hat) symbolizing the two sefirot of the intellect, Chochmah and Binah (see Chapter 4).

So is a head covering required? On the one hand, you would never see a man in a traditional house of study or synagogue without one. Traditional Kabbalists would surely agree that covering one’s head is as appropriate when studying from holy texts as it is when entering a holy space. But as my teacher insists, “all or nothing” is a false dilemma. It’s unreasonable to take on every custom and law at once. You can surely pick up a book that teaches about Kabbalah and learn from it without your head being covered. And I’m confident that God hears all prayers regardless of what you’re wearing on your head — or any other part of your body, for that matter.

Many people have also heard of a custom of wearing a red string tied around the wrist. This custom is often linked to the tomb of the matriarch Rachel in Israel, where you can obtain and wear a red string cut from long strands that have been wrapped seven times around the tomb. The red string is then made into a bracelet that’s worn as a protective segula (seh-goo -lah; amulet). Some speculate that the red string has some positive impact because it can inspire the wearer to improve his or her character traits by recalling the fine qualities of the biblical Rachel.

Some say that wearing a red string wards off the evil eye. The basic idea of the evil eye is that a person’s evil glance has power. There’s no physical evidence of such a phenomenon, but to me it isn’t a terribly far-fetched notion. A person’s evil glance or evil eye may not provoke absolute cause and effect in the world, but the negative thoughts and emotions behind those glances are real. The great sages of Kabbalah designated these glances as the evil eye, or ayin harah (ah -yin hah -rah).

Bottom line: Although there’s certainly nothing wrong with donning the red string, it’s not a requirement for studying Kabbalah.

You Have to Know Hebrew

You don’t have to be an expert in the complexities and beauty of Hebrew in order to be a Kabbalist. Nonetheless, it’s absolutely true that unless you know Hebrew’s complex grammar, whole areas of Kabbalistic teachings remain off-limits to you because the unique nature of Hebrew grammar expresses some of the most sublime ideas of Kabbalah.

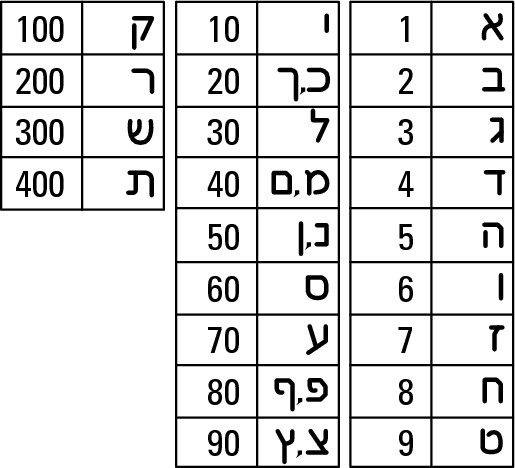

But it would be inconceivable to begin studying Kabbalah in-depth without some knowledge of Hebrew. Even a basic knowledge of the ABCs — aleph, bet, gimmel — is a big help. For example, the details in the Five Books of Moses as well as other sacred texts are based on the notion that every Hebrew letter has a numerical equivalent; aleph = 1, bet = 2, gimmel = 3, and so on. This system is called gematria (see Figure 17-1). Often, Kabbalists will offer fascinating interpretations of sacred texts by using this system. Many Jewish amulets have been based on the numerical value of Hebrew letters as well. For example, an amulet might have the numerical equivalent of a lucky Hebrew word or phrase on it.

|

Figure 17-1: Every Hebrew letter has a numerical equivalent. There are no numbers in Hebrew; just this system. |

|

Even the shapes of the Hebrew letters are objects of study for Kabbalists. And the name of each letter also carries significance. For example, the Hebrew letter bet, the second Hebrew letter, means “house.” The shape of the letter bet indeed looks like a house with one side open. For the Kabbalist, this letter reflects a powerful lesson about Abraham, who dwelled in a tent that was open on all sides so that he could eagerly go out and greet guests. That gesture of going out to greet guests relates to the sefirah of Chesed, which Abraham embodies. In other words, a simple drawing of the most primitive house with one side open becomes a reference point to the understanding of the wisdom of Chesed, giving, outpouring, charity, and acts of kindness, all of which are expanding outward, just as the sefirah of Chesed implies.

Students shouldn’t be discouraged by the close relationship between Kabbalah and Hebrew, though. One of the greatest Kabbalists who ever lived, the illustrious Rabbi Akiva, is said to have begun learning the ABCs in Hebrew at the age of 40!