Development: From the Good to the Best

‘All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible.’

—T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

‘Try to learn something about everything and everything about something.’

—Thomas Huxley, Quoted in Nature Vol. XLVI (30 October 1902), p.658.

‘Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.’

—Thomas A. Edison

10.1 Introduction

Development can mean the difference between the great and the good; the transformation of the mediocre into the excellent; it can be the difference between failure and success. ‘Executives who consider a job to be a set of tasks, miss the importance of developing people’ (Berson and Steiglitz, 2013, p.93).

Development is a lifelong progress that starts with the earliest human learning. Babies, children, and adults all develop at different rates based on their genetics, and their environment. Some people are more predisposed to picking things up, understanding other people and their surroundings. Some people learn very quickly while others need practice. In psychology, development just means change in a person over time. For example, physical growth and learning are developmental. In the context of human resources and performance at work however, typically development means deliberate effort, training, and learning that is intended to directly or indirectly improve performance or realise potential.

In common usage, training is different from development. The key to this chapter is development in the sense of really developing high potential. Training is part of development, and is important but is less interesting from the perspective of this book, and you’ll see why in a moment.

10.2 The Lessons of Experience

There are many ways to develop talented high potential people. Talented leaders provide much the same narrative of the influential factors in their development. Studies across organisations in different sectors as well as those within big corporations and across different corporate and national cultures, even different historical time periods, reveal the same story. Successful leaders who have proven to develop their talents mention six powerful learning experiences.

The first is early work experience. This may be a ‘part-time’ job at school; a relatively unskilled summer holiday job at university; or one of the first jobs they ever had. For some it was the unadulterated tedium or monotony which powerfully motivated them never to want to repeat. For example, one of the authors once worked at an unimaginably tedious job where the sole task was stacking newspapers into piles of ten as they came off a conveyor belt. For others it was a particular work style or process in a particular job or organisation the memory of which they have retained all their lives. This is something to select for: what type of work experience they had while young and what they learnt from it.

The second factor is the experience of other people, and it is nearly always an immediate boss, but can be a colleague. They are almost always remembered as either very bad or very good: both teach lessons. Usually it is how to treat others, or how not to treat others. The moral of this from a development perspective is to find a series of excellent role models, mentor-type bosses for the talent group.

The third factor is short-term assignments: project work, standing in for another or interim management. Because this takes people out of their comfort zone and exposes them to issues and problems they have never before confronted, they learn quickly. For some it is the lucky break: serendipity provides an opportunity to find a new skill or passion.

Fourth is the first major line assignment. This is often the first promotion, foreign posting, or departmental move to a higher position. It is often cited because suddenly the stakes are higher, everything is more complex and novel and ambiguous. There are more pressures: the buck stops here. Accountability and personal responsibility is greater than ever. The idea then, is to think through appropriate ‘stretch assignments’ for talented people as soon as they arrive.

The fifth factor is hardships of various kinds. It is about attempting to cope in a crisis which may be professional or personal. It teaches the real value of things: technology, loyal staff, supportive head offices, personal values, or experiences. The experiences are those of battle-hardened soldiers or the ‘been there, done that’ brigade.

Hardship teaches many lessons: how resourceful and robust some people can be and how others panic and cave in. It teaches some to admire a fit and happy organisation when they see it. It teaches them to distinguish needs and wants. It teaches a little about minor forms of post-traumatic stress disorder and the virtues of stoicism, hardiness and a tough mental attitude. Learning and persevering after failures.

Sixth on the list comes the management development education and experience. Some remember and quote their MBA experience; far fewer some specific (albeit fiendishly expensive) course. One or two describe the experience of receiving 360-degree feedback. More recall a coach or mentor, either because they were so good or so awful.

To the extent that leadership is acquired, developed and learnt, rather than ‘gifted’, it is achieved mainly through work experiences. Inevitably some experiences are better than others because they teach different lessons in different ways. Some people seem to acquire these valuable experiences despite, rather than as a result of, company policy.

Experiential learning takes time, but timing is important. It’s not a steady, planned accumulation of insights and skills. Some experiences teach little or indeed bad habits.

But three factors conspire to defeat the (good and rather valid) experiential model:

• First, both young managers and their bosses want to short circuit experience: learn faster, cheaper, better. Hence the appeal of the one-minute manager, the one-day MBA and the short course;

• Second, many HR professionals see this approach as disempowering them because they are ‘in charge’ of the leadership development programme;

• Third, some see experience as a test, not a developmental exercise.

Maybe leadership potential and talent should be defined as the ability to learn from experience, and apply that experience to the work. Equally, every move, promotion, or challenge should be evaluated by its learning potential.

10.3 Training and Competencies

Training is about teaching an employee how to do a certain task or job. It relates specifically to competencies (training is essentially the process of acquiring competencies). Competencies have been popular since the 1980s, and can be seen as the fundamental building blocks of any career (McClelland, 1973). Competencies are the basic things a person needs to be able to do to get their job done. Competence implies the minimum level of performance, whereas other words such as expertise or mastery imply optimal skill levels. Consider the definition of competencies by the Employment Department and NVQ’s definition of a competency: ‘something which a person who works in a given occupational area should be able to do’. A bit vague, but it means the right behaviour to get the job done.

Competencies can be broken down into elements of competency, and each can be assessed, using a practical or theoretical assessment, where people demonstrate the appropriate behaviour and performance. The following elements of a competency (Figure 10.1) are taken from a competency-based model for Aircraft Structural Technicians and Utility Arborists. Competencies lead into training programmes, because there are specific, limited and clearly defined outcomes of training, that can then be tested and measured.

Figure 10.1. Sample of Competencies and Occupations Adapted from ITA (2013a), ITA (2013b)

Every occupation is made up of a limited number of competencies (McClelland, 1973). Each competency may be, but is not necessarily, exclusive to a single occupation. For example, as shown in Figure 10.1, two very different occupations at Aircraft Structural Technicians and Utility Arborists have many different competencies. However, there are similar competencies in understanding the relevant regulations, workplace hazards, and personal protective equipment. The key idea is that each competency is important, and every competency is necessary. The limitation to competencies is the chasm between the competence and excellence of high flyers.

10.4 Developmental Processes

As opposed to training, which has specific timing, focuses on specific skills, knowledge and competencies, development is more broad and wide-ranging. While training is primarily to get up to minimum levels of performance, development is to maximise potential. It used to be that training was for entry and ‘low-level’ workers, while development was for higher-level managers and professionals (Winterton & Winterton, 1999). Figure 10.2 below highlights key conceptual differences between training and development.

Figure 10.2. Selected Differences Between Training and Development

Development is fundamental to moving from competence to excellence, from high potential to high performance. Development is the most important vehicle driving the development of potential; from the potential (possibility or likelihood) to do well, into actual performance when required. It involves developing new skills, applying old skills to new environments or tasks, and refining and honing other skills.

Typically the objective of development is to improve work performance. Many high performers (or high potential people) want development opportunities because they want to improve their own performance and self-actualisation. A further benefit of development is that it can help retention, as will be discussed in the next chapter.

Developing people is an opportunity for individuals to improve, but it should be equally seen as an opportunity for the company to develop people – to increase the capability of workers, with higher performance as a consequence of development. Approaches to development vary widely. Some employers are interested in providing (or selling) ‘transformational experiences’ and self-awareness. But when it comes down to it, most competent leaders will assume if they’ve managed to find and hire you, you have already managed to ‘find yourself’. The key to development should be that it is based on a clear conceptualisation of potential, realistic objectives and a plan.

10.5 The Goldilocks Zone of Development

Development is the process of directing, targeting and applying experience to maximise potential. As discussed in Chapter 5, experience is a fundamental part of high potential. Experience is central to development, but all experience is not developed equally. For people to develop they need opportunities to practice and learn. They need challenges to learn from, but not to be thrown in the ‘deep end’ without any help or support.

Good development occurs under conditions that are not overwhelmingly difficult, nor underwhelmingly dull and uninspiring. It could be described as the Goldilocks Zone of Development: not too easy that it’s effortless; not too difficult that it’s impossible. It’s similar to the idea of deliberate practice, but deliberate practice under the right conditions; both the internal dedication and right levels of difficulty; too easy and learning cools off; too demanding and burnout is imminent. The Goldilocks Zone is what astronomers affectionately call the circumstellar habitation zone – the narrow set of conditions in which life can develop.

Whereas practice can be completely focused and rehearsed, the Goldilocks Zone of Development can be in new and unfamiliar conditions, and learning new skills while using current skills. It’s not too hot, creating too much pressure to really be able to learn from successes and failures. Nor is it too cold, slow-moving, sluggish and unchallenging to promote any learning. Colvin (2011) refers to it as ‘effortful activity’: it is activity that is conscious, effortful, challenging, and deliberate. Lev Vygotsky (1968) described it as the ‘Zone of Proximal Development’.

That zone is something that is fostered internally by the person, and externally by leaders and organisations. One has to be focused, dedicated, engaged in the activity, continually thinking and reflecting upon the new challenges and experiences. At the same time, a strong leader or mentor will help the high potential person to understand and make sense of situations. An organisation can encourage (or inhibit) people’s desire to learn new things, explore new techniques and take risks and allow people to learn through successes as well as failures. Of equal importance is the ability to distinguish between individual error, and failures that affect the organisational goals.

Thus development should be a co-operative process. The employee, the person being developed, should be actively seeking that Goldilocks Zone, where the work is challenging, engaging, and helps to improve skills. It is the person’s responsibility to not just participate, but focus on learning from the work and to be part of the development process. To be thinking about the challenges, seeking support where required, reflecting on lessons learned and lessons that still need to be learned.

The person who believes they already know (or can do) everything, who believes everything is easy because of their overall mastery, will stagnate. They are in the ‘too easy’, too cold zone, and can’t see that there is a more challenging area that is waiting to be explored and developed. Overconfidence, arrogance, fear, or a leader without a strong vision and ability to push/inspire can cool off development.

Leaders, HR departments and colleagues contribute to the development process (and depend on the size, structure and particularities of the organisation). They create opportunities for development, inspire people to push themselves where appropriate, and support and coach them when and if they become mired in challenges beyond their current ability. They provide a structure for guiding development, and a support system to push the boundaries of the Goldilocks Zone.

It’s not uncommon for people and organisations to languish in either the too hot or too cold zones. Some organisations and people get comfortable in the cold zone, where things are going well, minimum performance is sufficient, sales are good enough. Some people who don’t see their personal development tied up in their work may be content to have steady, consistent, reliable performance in the cold zone, to save energy for their personal or family life. Organisations too, can become complacent.

It is also surprisingly common for people and organisations to stick in the ‘too hot’ zone. Instead of consistently meeting minimum performance standards, many organisations are in a constantly reactive state. Every day, every task is a fight against the newest most pressing challenge: customer complaints, legal challenges, staffing problems, leadership difficulties, insufficient funding, and poor sales.

There are innumerable problems that create an environment where the company and the people are constantly jumping from place to place, fighting fires, extinguishing emergencies, but never really settling down. Yet, the lessons are never learned, the major problems are never resolved and the bigger picture, systemic problems are never really dealt with or given the appropriate time or attention.

Many hospitals have physicians and nurses running from emergency to emergency, always with many things to do but emergencies, quite rightly, taking priority. Yet sometimes this means key problems with the organisation go unresolved and unaddressed. Politicians can become embroiled in the most populist current issues, the controversy of the moment, and react to the short-term concerns instead of meaningful, strategic, and long-term planning. Employees, leaders, or companies sling mud at each other in what can quickly become a race to the bottom, instead of developing and (improving) potential.

New managers will often micromanage, taking control of minor details instead of their key responsibilities. They take control of the things they have done well in the past, but neglect their new responsibilities. There is always something or someone who needs to be instructed and monitored, but never enough time to get everything done. This ‘too hot’ zone also inhibits development, because there is not time to think, learn, and reflect from the experience. People who are feeling the pressure, fatigue, and excitement tend to jump to dealing with the most pressing problem that they are already best able to resolve. There appears to be no time to consider priorities, take the time to learn how to do something new, and the cost of failure is perceived to be too high.

Good development is a dynamic process that requires co-operation and interest from the individual being ‘developed’, the organisational culture and relationships with colleagues or leaders. Personal relationships are an important part of development, particularly in the coaching or mentoring process. Not all development is based on relationships, but it will be challenging for anyone to continually develop within one organisation without strong social ties and respectful trusting relationships. Disconnections between cohorts, generations, organisational groups, departments, and management levels can easily develop when information is provided (feedback, recommendations, and advice) without trust or respect. It’s hard for anyone to hear criticism or their limitations described and when it comes from a colleague or leader where there is no relationship, it probably will not be well received.

Berson and Steiglitz (2013) describe how ‘leadership conversations’ are important to help new employees, or employees in new positions develop plans of action, define expectations, clearly communicate performance standards and develop relationships. They suggest that leaders should work to have ‘conversations’ in order to develop personal relationships and regular contact. The interaction should be about developing the relationship; contact is not just about listing tasks. Building relationships can lead into opportunities to use people’s skills and networks – both to achieve the organisation’s goals and to develop people. But, leaders need to stay in touch and keep up-to-date to know who has the unique knowledge, expertise or contacts – and need to have built the trusting relationships so that people are willing to disclose and use their talents and knowledge.

Not every characteristic can be developed. For leaders, learning to ask the right questions in the right way and learning to build honest and trusting relationships can be developed. Many characteristics cannot be developed. Personality, for example, cannot be changed without serious psychological intervention. Experience and motivation build on intelligence, but intelligence cannot be drastically changed (except in extreme cases like brain injury). Development is primarily directed at broadening range, depth, and suitability of experience.

Consider the following three stages of development:

Firstly – Before: Before training or development starts, it needs to be planned. One needs opportunities for new experience, whether they are specific training courses, or new on-the-job projects to learn new skills. It can be self-directed, when the person chooses training that will improve their own performance or potential. Opportunities for experience help to hone skills, applying them in new situations and learning more about the job, other jobs, other people and one’s own attributes.

Before the training begins, this may be choosing a task for a specific person, matching a group of people with a training or development programme, or designing a specific development activity for a group with a specific type of potential development in mind. Individually, it also involves understanding what motivates people to be part of development activities, what they hope to get from it, how important they believe it is, and how important the development is to their supervisor.

Secondly – During: Learning from training is the intended part of any training or development. But people always bring their previous knowledge, experience and expectations into development. This is an advantage, when people are curious and interested, considering how the new experience fits into their own career, integrating their new experience into their current knowledge. However, expectations can be a double-edged sword. Resentment, scepticism, or mistrust of a supervisor who assigned the development activity can bring in negative expectations and preconceptions that inhibit development.

Thirdly – After: Good development never stops. After completing a specific training programme, contemplating the lessons learned and reflecting upon them helps to improve the outcomes of the training. Reflection is useful, whether or not the training or development was successful, as it is useful to consider why. Reflection is important because it means carefully considering and reinforcing the lessons learned from previous development. It also gives a chance to direct future development. Good learning experiences mean challenges. They should not be easy. Good development opportunities will show the individual where their skills gaps are – and should help to shape objectives for future development.

Each of these factors link, and should be a dynamic process that incorporates continual opportunities, planning, learning, and reflecting on each stage of the process.

10.6 Planning Development: An Example

Take the example of local community development offices. The development office works with small- and medium-sized local businesses. Its purpose is to help those businesses grow by providing funding or other business support. One of the important jobs in the development office is an accountant. The accountant assesses proposals and business plans to make sure the development office is supporting financially viable businesses and plans. If we assume selection was done well, an accountant for the community development office will start the job with strong qualifications and will be fully capable of assessing financial plans and providing financial advice. The accountant would be intelligent, conscientious and hopefully have similar values to the organisation.

However, as many people quickly learn when moving from education into the workplace, there are more demands, complexities, and challenges in work than education or training can prepare you for. A good leader can prepare people for this shock, and in ideal cases, development starts with this realisation. For the new accountant in the community development office, numerical and financial acuity is a fundamental competency, but improving performance involves interpersonal skills and the ability to build relationships that some accountants may need and may not have learned at the start of their career. Part of the work of assessing small businesses is getting to know the people in the business, understanding their motivations, goals, and abilities.

Thus, a development opportunity for the accountant would focus on building up skills that are important for successful performance, improving performance or potential. It may start with formal training, an orientation, workshop, or course, and then would involve practicing more informally. Perhaps teaming up with a colleague who already has those skills and will provide some informal help and guidance, with on-the-job learning.

There are many ways to develop staff with potential. There are two primary dimensions of development that are helpful for understanding the range and breadth of development:

Formal vs. informal which distinguishes between whether the development is formal, explicitly part of the job and monitored/recorded formally. Informal experience can occur inside or outside the company, but tends not to be explicitly recorded or rigidly structured.

Knowledge vs. experience distinguishes between abstract learning and theory compared to actual practice. For example, it is the difference between learning about business plans and business models versus actually applying it, which involves getting to know and understand the person behind the business.

Figure 10.3 shows a matrix of development types comparing formal and informal knowledge and experience. The most effective development draws from each of the quadrants, and uses various aspects to build on each type of development.

Figure 10.3 Examples of Knowledge vs. Experience and Formal vs. Informal Development

Formal development of knowledge (typically training) can provide the foundation for development, teaching the basic skills necessary to be successful in the job and to teach employees strategies for enhancing their own development. Formal development experience gives people a chance to apply their knowledge and hone their skills and apply those skills to familiar and novel situations.

Formal development of experience involves structured and targeted applications of knowledge and experience. When done right, it usually has formal objectives, clear requirements, and success criteria. Essentially, it should be a method of directing and applying skills learned in training. It serves to reinforce the training, and should be a strong indicator of whether or not the training was successful. If a training programme does not improve performance, either the training was useless or the person did not really learn from it. Good training (formal) should provide direction for further experience to develop the skills: skills learned in training should be transferrable to the workplace.

Informal development experience can provide a novel or interesting environment for experimenting with new skills (potentially outside of a work environment), or to develop skills further, such as teaching colleagues. ‘Teaching as learning’ is an excellent example of this. After training, the person teaches one or a few colleagues the skills they have learned. It is less formal, because it does not happen in a classroom and may not be directly supervised. It’s a chance to practice the skills and apply them to a new and different set of circumstances.

Informal development knowledge can be imparted by coaching or mentoring. Coaches or mentors can be provided in an organisational environment, or can come from outside the organisation. Mentors can provide insider knowledge, advice, and guidance. Mentors can help to bridge the gap between previous knowledge and experience and future development. A coach can help a person to make sense of previous experience, and then can guide the person to future development opportunities that would be of the greatest benefit given current skills. It requires greater knowledge of the person, their abilities and history, and is an on-going benefit.

The key to successful short- and long-term development of high potential is integrating all types of development into an employee’s work life. Successfully combining these will improve development. Quick fixes are common practice, but are not necessarily effective. It’s common for development to be done on an ad hoc basis, development is done in a quick course to check a box off the good HR manager’s ‘to do’ list. Or, when a department has some money left over at the end of the year it is shovelled into training exercises.

The reality is short courses, workshops, and training exercises can be useful, but are not necessarily useful. Effective salespeople generate excitement about a course or workshops, making the training seem interesting, fun, and promise results. It’s easy to justify the expense by imagining any experience is valuable but that is just not true. Development efforts should be focused and integrated into performance objectives and long-term development efforts.

A great rule of thumb for testing out whether a development opportunity is valuable is to plot it in the development matrix. Use the question potential to do what?, keeping it firmly in mind. Does the development fit broadly within the context of the employee’s potential?

Firstly, put the development opportunity into the appropriate quadrant of the development matrix (for example, formal + knowledge). Are there applications where the knowledge can be used in the workplace? It should fit into the framework, and be reinforced by further formal and informal development, such as follow-ups and practicing on-the-job to test out the knowledge or skills.

If the development opportunity doesn’t connect with all quadrants of the development matrix one of two things should happen. One, drop it. Save yourself the time and avoid the glibly packaged schoolyard activities. Two, ask more questions and learn about the realistic outcomes. If it is unlikely it will translate into valuable experience or have any effect on performance or potential, refer to one.

Not to say that something that is not directly related cannot be valuable experience – but there should always be a cost-benefit analysis. If something is sold as a great development experience, and comes with a high price tag it needs to be able to demonstrate direct links to performance. Many informal (and low cost) activities – even hobbies or ‘extracurricular activities’ can lead to strong connections with other development efforts. Hobbies can lead to developing new skills, or developing informal networks that can be a source of experience or a place for informal coaching.

10.7 Types of Development

The first part of development in any organisation is getting oriented, learning what to do, and meeting colleagues. In Human Resources this is called onboarding; psychologists would call it socialisation; most people would call it orientation. Essentially it’s a process of learning about the job, learning about the company and learning about the people with whom they will be working.

A) Orientation and ‘Onboarding’

Most jobs involve an initial period of formalised training that involves learning about the specific skills required for the job, the expectations of the organisation and future colleagues. It usually has a specific time duration (e.g. a half-day, one week, one month) and may be followed by some sort of testing or assessment of characteristics or skills, to make sure they are ready to start work. A more detailed orientation process that involves introduction to both the systems, people and social context of the organisation (referred to as onboarding) introduces new employees to the work. This should be an introduction to the organisation, but also the development process. What the employee has to do to initiate further development (document the process), who to work with, and who to ask questions about various things.

Allen and Bryan (2012) describe six important recommendations for improving the ‘onboarding’ process, based on Van Maanen and Schein’s (1979) pioneering work into socialisation:

1. Formal. Specific activities that are designed to help new employees become accustomed to the organisation and colleagues. Special groups and activities arranged formally, with specific purposes. These help new employees to learn and reduce anxiety, by providing easy steps to learn about the job demands and the group. They are planned new-hire lunches, on- or off-site activities. These should have clear and consistent messages to convey job responsibilities, expectations and culture.

2. Collective. Combined groups of new hires help new employees to get to know each other, and to feel a sense of camaraderie that may not be initially possible with entrenched employees. These groups should be designed to create a sense of excitement about opportunities to work within the organisation, and the organisation is supportive of their development. Otherwise, informal, unstructured, and unsupported groups may develop a feeling of ‘us vs. them’. When done well, this creates a connected group who feel supported and accepted into their new role.

3. Sequential. The order of events should be pre-arranged, designed, and clearly described. This helps new hires know what to expect of the initial onboarding process, and feel more prepared to start. When new employees are able to prepare they are more likely to feel greater control and be able to meet expectations.

4. Fixed. The timing of onboarding events should be clear, not just the order. For example, a group of new hires would receive a specific schedule of events for new hires. All the various elements have a time and date, with clear description. Many people are anxious about new jobs, so fixed times and dates allow people to prepare, reducing anxiety and uncertainty;

5. Serial. People already experienced in the organisation, such as experts or leaders, are part of the introductory process. These should allow opportunity for interaction and building relationships with these ‘insiders’. It helps people feel that they are really part of the organisation, understand the inner workings, and are getting the right contacts and building the right connections early on. It helps to learn who to ask questions and who can help solve problems. It also helps new employees identify possible mentors and role models.

6. Investiture. When the process involves early feedback and information about the position, along with clear social support, it helps new employees feel like a welcome and important part of the organisation. This helps new employees feel willing to provide their own contribution to the organisation, as compared to divestiture socialisation, which encourages conformity, but not integration into the team.

Onboarding, of course, must be relevant and appropriate to the position and the organisation. It sets the tone and is an opportunity to convey performance and social expectations. It also leads into further development opportunities – lack of onboarding, or poorly planned onboarding, conversely signals there may not be a strong or coherent development path.

An example of exceptional onboarding actually comes from particular university student unions. Most university student unions organise a series of events for new students, in the sometimes infamous ‘freshers’ weeks. Some who work in university unions have learned the importance of starting off well. The onboarding and orientation events set the tone, and for students the transition can be a huge change. The transition into a new organisation is often less drastic, but the importance of a smooth transition should not be underestimated. The Courtauld Institute of Arts is a good example of this, because it’s a specialist and elite institution, well known for producing High Flyers in the art world. Róisín O’Connor, President of the Courtauld Student’s Union, describes the importance of these events:

‘It is a chance for new students to explore the city and what’s available to them. It also allows them crucial bonding time – peers must become family away from home and they can learn whom they want to spend their time with. Good freshers’ events are very important for building what can become lifelong friendships.’

Similarly, in companies new recruits must be given opportunities to develop relationships, meet prospective colleagues, leaders, and mentors. It’s a time to explore the organisation, the systems, the culture and the opportunities. A strong start helps people develop the connections, knowledge and social support needed to be successful at work. Yet, it’s not a simple or easy process.

‘The success of freshers relies on how comfortable the students feel about the Students’ Union; how excited they are to become part of the wider student community; how interested they are to partake in societies; how confident they are in feeling that their voice will be heard and appreciated.’

It depends on the organisers, as well as the new ‘recruits’.

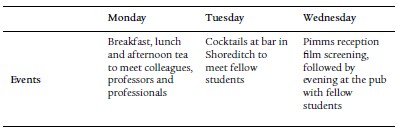

Like any organisation, the Courtauld has a unique history, culture, and mission. It is a small university with about 250 new students in 2013 (mostly postgraduates), and its reputation for excellence means expectations are high: and this is true for any organisation or company renowned for high quality. The orientation sets the tone, so disappointing students or new employees before they even begin can be extremely demoralising; an excellent onboarding experience can be invigorating and starts people off engaged and excited. Although student onboarding involves more ‘fun’ and typically involves significantly more alcohol than one would want to introduce to the workplace, other organisations can learn from student unions like that of the Courtauld to provide informal and engaging experiences. A sample of the Courtauld’s ‘onboarding’ events includes:

Figure 10.4 Extracts from the Courtauld’s ‘Freshers’ Events

The culture, values and purpose of each organisation will influence what types of events are useful, entertaining and appropriate.

B) Training/Workshops/Classes

These can be either internal or external, but have a specific time period (e.g. a half-day, day, weekend) and typically have a specific purpose. They are intended to teach a specific skill, or knowledge about a certain area. Good training exercises have a specific purpose, clear time period, and are geared toward a specific outcome. For detailed information about planning training see Berger and Berger, 2004. Ideally there should be direct linkages to future work, along with practice and follow-up evaluations.

C) Task Force Assignment

Specific tasks at work can either be directly related to a person’s current job description, or outside of their current job scope. A task force is a good way to develop skills that were learnt in a workshop or class. The purpose of a task force assignment is typically practical skill development. In other words, there should be a specific, well-defined task along with success criteria (both of the task and of the development). To be successful, the person assigned to the task should be:

• Capable of succeeding (i.e. high potential on that task);

• Able to develop new skills, or hone existing ones;

• Willing, or motivated, to succeed.

The task should be limited in both time and scope. It has clear and specific objectives, and the person knows when, why and how the task will conclude. For example, if the task force assignment is to recruit three new employees with a specific set of skills and characteristics to the department by the end of the month.

D) Rotating Assignments

Rotating assignments are thus named because one is moved between positions or locations. Unlike task force assignment, it is not limited to a specific outcome or objective, one is required to fill an entirely new position (although the position may be similar). Of course, all of the concerns with putting untested or unknown people in unfamiliar positions are relevant here. Before placing people on rotating assignments, it is essential to ask the same, recurring potential questions. What characteristics predict potential in the new assignments/positions? (Chapters 3–6) How much overlap is there between the current position and the prospective position? (Chapter 8) What is the potential (and consequence) of failure? (Chapter 7). Greater similarity of position reduces uncertainties of a person’s potential to perform well and learn from experience, but similarity provides fewer opportunities to learn new skills and adapt to new situations. Rotating assignments require excellent assessment of potential, clear goals, ‘areas to develop’, and should target the Goldilocks Zone, getting the assignment and the person ‘just right’.

E) Teaching (As Learning)

Teaching other people about the job, the work or skills is an excellent way to practice skills and develop them with other people. It is not simply a lecture or description, but working with others personally and interactively to impart skill. It is real and practical training. For example teaching through learning can be an important part of learning a new language. Teaching others the vocabulary and grammatical rules helps to reinforce the knowledge and understand that knowledge in a social context. It also helps to identify any skill gaps, as sometimes, when teaching (or trying to teach) one begins to realise both the extents and limits of their own knowledge and ability. Successful training and development naturally should lead to pride and satisfaction from achievement, as well as competence. Teaching others is a great way to demonstrate experience, and to reinforce previous experience. It is a natural reward for successful development because it recognises the success of those who have it.

F) Activities Outside of Work

Development is not always limited to work, and is not always something leaders, managers or HR departments can oversee. This can be much harder to define, guide, and manage, but is equally important. Activities outside of work, unlike most other developmental processes, are primarily the responsibility of the individual, not the company.

This could be learning leadership skills on a club or sports team, meeting new and interesting people in community or non-profit groups, clubs or charitable works. Or it can be when seemingly unrelated activities provide new knowledge which eventually translates into insight at work.

G) Coaching and Mentoring

Coaching is one-to-one advice and support for a specific task or issue. It is relatively short-term but is intended to be a closer, deeper look with specific advice and action planning. Mentoring is a longer term relationship for advice and recommendations that may be less focused on specific issues, but the mentor is available for guidance or advice and general support. Coaching is discussed, in detail, later in this chapter.

10.8 Developing High Flyers

Potential, of course, varies. People with high potential, by definition, have a greater capacity to develop from development opportunities and will learn more quickly. People with lower potential should not be excluded from development. Even those with more limited types of potential can still learn to do certain tasks better or more efficiently, and occasionally those judged to have low potential will rise to challenges and surprise even the most experienced assessor. Stifling opportunities drains the talent pool.

One way to look at development is to compare foundational and growth potential. Those with low foundational potential are likely to struggle with many of their responsibilities, those with higher foundational potential will be more successful at the core elements of their job. Those with low growth potential are unlikely to greatly improve their skills or their performance in their current role significantly. High growth potential means that person is likely to learn new skills, improve their performance, and may be able to use that growth potential to advance into new positions.

The focus inevitably falls on those judged to have the highest potential; the rising stars. The high flyers of the organisation have all the right traits, who learn quickly from experience, are motivated to excel and have seized opportunities available to them. Most people in the other three categories can still benefit from development, and the majority of people are ‘average’, in the middle, who are competent, mostly do a good job, but are often forgotten as people who can benefit from development.

Thus, people can be classified (broadly) into four development groups.

1. The Underachievers barely (or do not) meet the minimum requirements for the job. They don’t have the basic skills or abilities, and are unlikely to greatly improve. At best, this is because of a mismatch between person and position, and they may have higher potential in a different type of job within the same organisation. At worst, there may not be a position for them in the current organisation. Development for this group may focus on learning the skills for a different position, or low risk task force assignments to discover what jobs they are suited to.

2. The Strong and Stationary are fully competent in their current position, and have a high potential to continue to perform well in the same position. They will benefit from some development opportunities to improve their current performance, but their performance is unlikely to change greatly. This can be seen as a weakness or a strength. Development for this group is for retention as much as it is to improve capability.

3 The Poorly Placed have a high probability of learning new skills and improving their performance, but they may have challenges with the core tasks. This could be because they have not yet learned the skills, or because their attributes are not a good match with the position. Typically development activities for the poorly placed should focus on finding a better job match, giving people the opportunity to grow and develop into new positions.

4. The Rising Stars are the future High Flyers. They have all the right traits to do their job well, likely already have strong performance, and are likely to improve their performance, learn new skills, and be capable of moving into other positions. This group should get the full suite of development opportunities, either with the aim of improving performance, training experts and specialists, or with the purpose of moving the rising stars into managerial or leadership positions.

Figure 10.5 Matrix comparing development objectives for growth and foundational potential

A critical component of potential is the ability to learn from experience. Equally, every move, promotion or challenge should be assessed by learning potential. The capacity to meet and learn from a challenge is more important to potential than past experience at an identical task. While others may be focused on getting the job done, High Flyers are continually interested in new experiences, and developing their own potential. In a study of High Flyers, Galpin and Skinner (2004) found that High Flyers were clear about the value of developmental processes. They noted the order, from most to least valuable, of processes as:

1 Mentoring;

2. Job Rotation;

3. 360 Degree Feedback;

4. Qualifications Support;

5. Coaching;

6. Interpersonal Training;

7. Management Development;

8. Technical Training;

9. Career Counselling;

10. Buddying;

11. Career Development Resources.

It is important to note that formal training and basic institution resources are not the most valuable developmental tools. The most highly rated development processes provide honest and constructive feedback and advice (mentoring) or direct and applied experience (job rotation). These are some of the most complex and most difficult developmental processes to administer, but are also the most valuable.

Galpin and Skinner (2004) noticed that High Flyers had very strong views about what they believed was good for their own development and wanted to be ‘in the driving seat’ of their development. ‘Clearly, there is a need to ensure that there is a healthy balance between the organisational performance and the individual’s development, and that the high flyer does not get rewarded for leaving a trail of destruction behind them’ (p.114).

Development, particularly for demanding, engaged, and career-mobile High Flyers is not easy, but it’s necessary, and is one of the most important activities to keep the best and the brightest.

Students of the magical (but occasionally disillusioned) MBA or the part-time degree know the sacrifice that is involved there. If there are 24 hours in a day and you sleep another third, how much of the remainder do you give to your friends/family and work? The mastery of any skills comes more easily to the talented but all skills take practice. This includes all those skills one goes on training courses to achieve: presentational skills, negotiation skills, counselling skills and selling skills.

10.9 Measuring Development

Traditionally, there are four measures of development success. The first and easiest is the ‘happy sheet’ method where trainees report on their reactions and also perhaps how much they did and didn’t learn. These are not always reliable. Trainees can be deluded as to how much they learnt. Others are ingratiating or sabotaging, giving unrealistically positive or negative feedback on all or specific aspects of the course.

The second is the classic before and after examination; test (for knowledge/skill) before the course, and then immediately afterwards. Make the test hard before and easy after and you can ensure impressive results. Or the other way around of course if you want to prove the course didn’t work.

The third is to get others to rate the trainee who works with or for them. Thus they make a before-training assessment and an after-training assessment. They may be accurate and honest . . . but of course they may not.

The fourth and best method is, of course, to measure not what people say, but what they do, or better still, what they produce. This makes the sponsors really sit up. Imagine sending people on a five day sales course which increases sales revenue by twenty per cent over the next six months. Now you are talking! But there are two major problems with this ideal solution: having really good measures of an individual’s performance and being sure their output is uniquely due to their own ability, effort and knowledge.

Another issue is whether training actually applies to different situations. The issue is called transfer of training and it may be the Achilles heel for trainers. Put people in a safe, supportive, comfortable environment and they may learn and readily display a variety of skills salient to a business. Pluck them out of that safe cocoon and three weeks later they appear to remember nothing. But something can be done. Four features considerably improve transfer of training.

1. Feedback

Feedback is a central component of all learning. The question is how to obtain honest and accurate feedback after the formal training has stopped. Trainees need to learn to ask for feedback or the signs of feedback. Certain tasks can have feedback mechanisms built into them. The microchip can be used to signal to people that they have been sitting or standing for too long or short a period of time. More importantly perhaps, new programme attendees need to be told it is their duty to help those on courses to maintain, even improve, their skills. All too often people who return from skills-based courses are ignored, even punished. Skills need to be practical and reinforced. In this sense the whole organisation needs to be ‘on the course’.

2. General Principles

Teaching general principles is essential for generalisation. This means giving the big picture, and even the theory. The idea is to provide a framework for learning – the greater understanding of why. If people do not know the general principles they cannot easily adapt or see how differences between the training and work situation matter or not.

3. Identical Elements

Identical Elements are a great help though not always possible. This refers to the self-evident point that the closer the training is to the real situation the better. Given the correct identification of the situation (perception), training should mean learning how to respond most appropriately. It’s about making training as realistic as possible and tying it directly into work tasks, and that refers to selling equipment, people and the like. Posh country hotels and cosy training rooms don’t quite cut the mustard.

4. Overlearning

Overlearning is about achieving automaticity; doing something with little thought. Surgeons, pilots and the like can act quickly and thoroughly on extremely complex tasks without apparent thought. What they do has become second nature to them, and this requires serious practice. Transfer or generalisation of training is a complex issue, and there are many different types of generalisation, such as:

• generalisation over time;

• generalisation from the training time to the future;

• generalisation over situations: from the safe and cosy training room to the complicated hard world;

• generalisation over skills: from one set of particular skills (negotiation skills) to a similar set (selling skills).

All are important though the first two are the most significant and situational generalisation may have many subtle features. This is because work-based behaviour depends not only on individual skills and motivation, but also, crucially, on group norms. There are famous cases of individuals trained to do X things in X minutes comfortably (type 100 words per minute or deal with one customer every three minutes), but who struggle when faced with the much higher output rates that the work group finds acceptable. This is not a training issue, but something embedded much deeper in organisational or cultural values.

10.10 Does Coaching Work?

More and more organisations use executive coaches to help develop those identified as high potential. But what evidence is there that it works in the sense that it helps realise a person’s real potential? What is the active ingredient? Academics have tried to provide both an answer and a percentage; that is, how important each explanatory factor is. Interestingly the four factors apply (roughly) equally to all forms of counselling, therapy, coaching or what ever the help is called. There are four major ingredients.

First, client factors: It is, in short, more important to know who (what kind of person) has the problem than what the problem is. This accounts for a whopping 40 per cent of the effect. It’s called readiness for coaching. It is a mixture of willingness and ability to learn, to change, and to embrace challenge. The coach needs to assess and then stimulate readiness, and remove barriers and resistance to moving on. Furthermore, the professional needs to respond to the client’s preferences. Some (they are called internalisers) want insight; others (called externalisers) want to see problems solved. Much depends on whether the client is a conscript or a volunteer; if the latter, best results occur when the volunteer knows generally what to expect. This is why there is a first meeting, prior to the ‘sign up’.

There is a bit of a paradox here. If 40 per cent of the success of coaching comes from client dispositions then coaches can, at most, take only 60 per cent of the credit for the magic they perform. Beware of coaches that take too much credit. Some clients are eminently coachable (and just need a nudge in the right direction) and others are not. Often, those who need it most resist it most, and vice versa.

Second it’s the relationship between coach and client. The coach can explore and exploit the therapeutic alliance. It’s about collaboration, consensus, and support. Success depends on an effective and affective bond. Again, this has to be tailored to the client. Some people want direction, others want support. There are widely varying desires for the namby-pamby approach. It is about building and maintaining a positive, open, productive, and hopefully transformative alliance. However it should be pointed out that it is the client and not the coach’s explanation of the alliance that is important: coaches need to check this fact with their clients regularly. The distracted, fatigued or unprepared coach is a poor coach. The alliance is usually based on set and agreed goals and tasks.

The third ingredient that buys you 15 per cent is the old fashioned quality, sometimes called hope, now called expectations. It is about expectation of improvement, finding new paths to goals and ‘agency thinking’: the belief that success is a result of effort. Coaches speak and leak the message that successful change or progress is possible.

The fourth ingredient is the application of every/any theory and therapy. It accounts for 15 per cent of the power of coaching: the use of healing rites and rituals. The coach’s background influences their focus. Whilst some look at organisational competition, conflict, dominance and power, others may look at self-awareness and encourage personal SWOTS: the standard old strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats.

Theories organise observation. Some coaches share them with their clients, others don’t. Clearly the good coach needs to know what works for whom and why, but coaches also need to know about the business world and the dilemma of conflict of interests between the client and the organisation.

The client–coach mission and relationship is a bit like the patient–therapist one, but there are differences. Typically patients have more serious problems and poorer adjustment than business clients. Therapists work at a deeper emotional level than a coach. Therapists see more of the patient and contact is nearly always face-to-face. Coaches focus on the workplace, therapists on functioning in day-to-day life.

Patients often seek personal growth and alleviation of suffering; coaching clients enhances work performance. Coaching clients seek to enhance their emotional intelligence, political prowess, and their understanding of cultural differences. They want more insight into themselves and their world of work; coaching only works if the client is able, ready, and willing. It works well if the bond is good, and if the coach instils hope for change. Would an internal mentor do as well? Perhaps, but the external, unbiased objectivity of an outside coach is often very preferable. Ideally one can have honest and respectful conversations with intelligent, insightful and honest people inside and outside the company, but those people are not easy to find.

10.11 Why Training and Development Fails

Despite the effort, money and time some companies dedicate to training and developing talented people, many feel it frequently fails. But why? Below are a number of reasons for this all-too-common event:

• Failure to predetermine outcomes relevant to business needs of the organisation. Unless one sets out a realistic and specific goal or outcome of training, it is very difficult to know if it has succeeded or failed;

• Lack of objectives, or objectives expressed as ‘will be able to’ rather than ‘will’. There is a difference between can do and will do, often ignored by evaluators;

• Excessive dependence by trainers on theory and chalk-and-talk training sessions. This method is least effective for the learning of specific skills;

• Training programmes too short to enable deep learning to take place or skills to be practiced. The longer and more spaced out the programme, the more participants learn and the more it is retained;

• Use of inappropriate resources and training methods which have to be considered beforehand, particularly the fit between the trainer and the trainees’ style;

• Trainer self-indulgence, leading to all sessions being fun sessions, rather than actual learning experiences;

• Failure to pre-position the participants in terms of the company’s expectation(s) of them after training. This means having a realistic expectation, per person, of what they should know, or should be able to do after the training;

• Failure to de-brief participants effectively after training, particularly as how best to practice, and thus retain the skills they have acquired;

• Excessive use of ‘good intentions’ and ‘flavour of the month training’, rather than those known to be effective;

• Use of training to meet social, ideological or political ends, either of trainers or senior management. That is, training is not really about skill acquisition but rather about a fight between entrenched and opposed colleagues, or a fight between various departments.

10.12 Conclusion

Development is a lifelong process that has a greater span than any individual career or job. Some people are extremely ‘developable’ whereas others are resistant or unable. There are many ways to develop people, because development is a process that builds on already available skills, and uses key traits like intelligence and personality.

Employers who want to develop high potential must begin development from the very first day with effective orientation procedures, ongoing training and real knowledge of employees along with constructive relationships. Development cannot always be structured and formal, and the ‘good lunch’ method described in Chapter 8 may be one of the best ways to assess and direct development opportunities.