Types of Potential and a Model of High Flying Potential

‘All I require from myself is not to be equal to the best, but only to be better than the bad.’

—Seneca

2.1 Introduction

We have discussed ideas, theories, and definitions of High Flyers and high potential. It is also the intention of this book to provide a clear and useful individual difference model of high potential. We believe it is most important that the model is valid, in that we can demonstrate links with performance and potential through it. We also want it to be useful and comprehensive.

We believe a good theory should be:

1. Important: it deals with issues that really matter, as opposed to trivial, limited, inconsequential ideas. Psychological theories based on psychotherapeutic observation or student studies in the laboratory often run the risk of being trivial. We believe it needs to be important to people at work.

2. Operational: the theory allows the meaning of a concept to be clearly defined and measured. This ensures precision, which is essential for usefulness.

3. Parsimonious: the theory should be as simple as possible, but not more so. Efficiency without sacrificing validity.

4. Clarity: good theories are easy to understand and apply to real situations, both in everyday life and at work. The clearer the language in a theory, the easier it is to apply it to observations of people in order to understand them better.

5. Valid: theories should make predictions that are testable and can be objectively validated.

6. Stimulating: a theory should be capable of provoking others to thought and investigations. Important as this goal is, it cannot be an important criterion until the above factors have been confirmed.

7. Contextual: the theory should be able to state in which contexts the processes do and do not occur. That is, it is important to describe how social and cultural forces affect the processes.

Our objective is, then, to bridge the gap between science and practice: to create a measure and a model of personality and potential that is scientifically valid, useful, and usable. We will start with a framework for understanding potential and our model of personality traits useful for measuring potential. The purpose of identifying High Flying personality traits is to better understand the still poorly understood link between personality and potential. Although the relationship has been explored, it has not yet been explained.

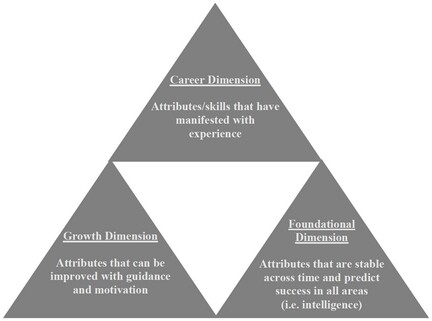

Silzer and Church’s (2009) three dimensions of potential are especially important when looking at personality traits of high flyers.

2.2 Types of Potential

It is clear Silzer and Church (2009) provide the best starting place for a framework of potential. Their framework describes the three key dimensions of potential. The three dimensions are well-defined enough to be useful, while being broad and adaptable enough to be useful and applicable to different work and careers.

A) Career Dimensions

Career dimensions of potential are specific attributes that lead to success in a particular occupation or job. These dimensions tend to be specific skills that can be demonstrated at varying degrees throughout a career trajectory. Career dimensions can be both learned and developed through experience; experience is essential for career dimensions.

One must be cautious in using career dimensions as a measure of potential, because by their very nature, the absence of career dimensions does not necessarily mean a person does not have any potential in a particular area; people change jobs and careers all the time. Sometimes, it means learning new career dimensions from scratch. For a chef, an important career dimension is cooking ability. Even the most culinary-challenged person may be able to learn new skills.

Career dimensions are mostly specific to certain positions. For example, the career dimensions for an entry level position are primarily technical or functional skills. Typically these will be the knowledge or ability to perform a specific task or set of tasks. These skills can take anywhere from a few hours to learn (in the case of a cashier), to years (an airline pilot or brain surgeon). Career skills can be advanced or complex, like building and repairing engines, but are only applicable to a limited range of jobs. We will discuss the work of Holland later, who argues there are essentially six clear, identifiable career types.

Career dimensions are important for hiring new employees. Career dimensions are typically the first (and sometimes only) consideration during hiring. In fact, career dimensions are one of the most common measures employers use, hence why CVs ask for previous experience and credentials. This can be appropriate when seeking a person for a specific position (e.g. you need someone to do a job right away, and be able to perform well right away), but it isn’t always the best. Always ask the question: What do you want this person to be able to do in the long term? The key question about career dimensions is, ‘What do we need the employee do be able to do?’ In other words, ‘What skills, education and expertise do we want?’ Career dimensions can be acquired and developed, whereas this is less so for other dimensions.

B) Growth Dimensions

Growth dimensions of potential are aspects that affect development and improvement. They moderate potential to improve and succeed and are relatively stable over time. Growth dimensions can interact with environments or situations. Growth potential can be a combination of internal characteristics of the individual and can also be situational factors. For example, a person who is very interested in a particular area may be more focused and learn faster. An encouraging and supportive teacher or mentor can further improve the person’s growth. Intellectual curiosity is perhaps the simplest and best marker for growth along with motivation and determination to succeed.

Growth potential can partially be identified ahead of time, for example: interests, propensity to learn, adaptability and ambition (which will be discussed further in Section 2). An individual’s growth potential is only a partial component that interacts with the situation, so an individual with growth potential is unlikely to thrive in an environment with poor leadership, or when not given opportunities to learn and develop. Capability needs opportunity.

Growth potential is important to identify because the greatest gap between current performance and potential is bridged or inhibited by growth potential. Growth potential may promote success in certain environments but may not be realised in others. Toxic situations and damaging leaders can also distort growth potential and make people develop unethical or undesirable attributes, which we will discuss in Chapter 7.

C) Foundational Dimensions

Foundational dimensions of potential are basic, stable characteristics that predict success across the board. Foundational dimensions are consistent across time so are excellent at predicting short- and long-term potential. Foundational dimensions are those attributes that contribute to success in any career, job or time. Intelligence (Chapter 3) is the prime example of a foundational dimension of potential, because it is generally and consistently useful.

Situational factors will only have limited effects on foundational potential. Foundational dimensions are quite stable across the adult lifespan, and can only be changed with serious intervention (see Edmonds, Jackson, Fayard, and Roberts, 2008 as cited in Silzer and Church, 2009).

Figure 2.1: The Three Dimensions of Potential

2.3 Potential to Do What?

The reason we are building on Silzer and Church’s dimensions of potential is because it is the most broadly applicable and best framework currently available. The specific question, potential to do what, is also a question for you, the reader, to consider. Thus it can be applied to policy and strategic planning in a multi-national organisation; a specific position in a small company; or even your own work, career or business.

If someone has high potential to be successful in a particular job, direct experience may be ideal if the intention is to hire someone who will be able to perform well at work immediately. Low growth potential can be undesirable if the purpose of recruiting is to develop a talent pool of future leadership talent. Yet, if the objective is to find talent and a strong consistent performer who wants to stay in the same job, that will be a very different type of potential. Much is made of growth potential, which is of course important, but it risks neglecting people with valuable talents whose value is not identified, because they don’t fit into a limited description of high potential, or potential is confused with value.

It is easy to forget the contributions of someone who does the same job for a long time. But, there are many roles in an organisation that are valuable, jobs which are most easily overlooked when they are done well. Not everyone needs or values rapid promotion, ever-increasing responsibility, or great rewards. For some, success means balancing work life with personal or family commitments – and there are many jobs for which high potential and success can mean consistent performance and reliability.

2.4 High Flying Personality Traits

Linking the concepts of high potential and personality are challenging, but based on what we know about personality should be relatively straightforward:

• First: Personality is relatively stable from early adulthood onward. It cannot be learned or taught, so is not primarily a career dimension of potential. It is an important constant, so it is a useful early indicator;

• Second: Personality is rooted in neurological structures. Brain structure and biochemistry are linked to personality, although it is not as simple as specific personality traits existing in certain ‘areas’ of the brain. This is still an area of ongoing research;

• Third: Personality traits interact to influence behaviour, moods, and thoughts. Although each is described individually, they are not (to use the statistical term) orthogonal. When considering two personality combinations, a ‘High A, High B’ compared with a ‘High A, Low B’ can manifest very differently in the workplace. Although the two are similar in ‘A’ and different in ‘B’, and may be compared as such, there are important differences between personality traits. Interactions create unique patterns of thoughts and behaviours;

• Fourth: Some personality traits may be better suited to certain careers, but no personality traits are exclusively required for a job, task, or career in the same way as knowledge or experience.

Thus, an overall model of potential must account for both the highly variable elements of high potential (like learning the right skills), to the very stable characteristics like intelligence. Career dimensions of potential are too occupation- or position-specific for a general measure of success; growth and foundational dimensions of success lend themselves to generalisable measures, such as High Flying Personality.

Personality traits may be foundational or growth dimensions because they can directly and indirectly affect performance (Dragoni et al., 2011; Linden et al., 2010; Seibert et al., 2001).

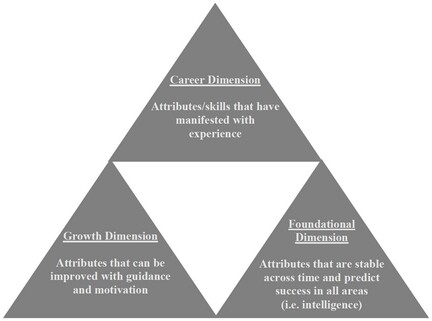

The High Flying Personality Inventory (HFPI) is a six-factor model of High Flying personality traits, which is based on how people think and behave at work. The HFPI was specifically designed to measure personality traits that affect success at work, and the capacity for high performance and leadership capacity.

The only stable characteristics that have been consistently linked to success are cognitive ability (Dragoni et al., 2011; Ree and Earles, 1992) and personality traits (Barrick, et al. 2003; Ulrich et al., 2009). Cognitive ability tests are widely available and well-validated (Bartholomew, 2004). The largest gap in current research on potential and success is a measure of personality at work that can be used in applied settings to predict potential. MacRae (2012) studied nine personality traits and related characteristics associated with success and leadership potential. Then, all of the traits were recombined as distinct factors, optimised for validity and measuring for assessing potential at work.

Figure 2.2: Recombination of Personality Traits for Six-Factor Model

A) Conscientiousness

‘I have always observed that a man’s faults are brought forward whenever he is waited for.’

—Nicholas Boileau

Conscientiousness is one of the key traits that help with nearly all jobs and tasks. It is rare to see the word conscientiousness on a job description, but when people say self-motivated, disciplined, organised, or punctual, they are essentially talking about conscientiousness. Conscientiousness is characterised by self-discipline, organisation, and ability to moderate one’s own impulses (Costa and McCrae, 1992).

People who are conscientious like to make (and stick to) schedules and plans; they like to have goals and objectives and can motivate themselves to meet those goals. The conscientious worker is punctual, organised, and meets deadlines. Conscientiousness is a very strong influencer of people at work. Of all personality traits, conscientiousness has been most associated with strong performance and success in almost all areas of work (Barrick et al., 2003; Costa and McCrae, 1997; Linden et al., 2010). This feature makes the conscientious worker stand out from less conscientious colleagues.

People who are conscientious like to plan things out, keep diaries/agendas, are on time, meet deadlines, as well as focusing on clear goals and achievements. People who are less conscientious are more casual, see appointment times more as guidelines than requirements, enjoy spur of the moment decisions, and are more flexible about timing and timelines. Nearly all conscientious workers will be conscientious throughout their entire work life. This means someone who is conscientious is likely to work hard during a training period to learn the appropriate skills; will be a diligent worker; and will strive to do the best they can at their job.

A consistent trait such as conscientiousness is fundamental to how a person behaves and performs at work. It is a foundational dimension of potential. If the objective is to hire someone with reliable performance, conscientiousness can be a good indicator of long-term behaviour.

Conscientiousness is useful in most occupations. However, it is important to remember (and this is true of all personality traits) that high conscientiousness is not always essential, and conscientiousness does not always translate directly into performance. Average conscientiousness is more than enough to do most jobs fairly well. High conscientiousness is useful, but not necessary to be successful in every position. Furthermore, there are benefits to low conscientiousness, although not all of them are related to work.

One of the challenges of constructing personality scales is to find positive ways to describe what can be seen as unfavourable. The results, in conversation, with people with low conscientiousness may seem initially surprising to someone who has a very different personality. One person with moderately low conscientiousness said: ‘I’m easy-going, adaptable, and things in the future don’t worry me too much because I’m just not thinking about them yet. I’m not too stubborn or fussy, so I have more fun!’

Conscientiousness alone is not always required, because its effects can be mitigated by good leadership, conscientious colleagues, or good motivation. People who have low conscientiousness may have trouble planning, organising and self-motivating but once they are motivated they can be very hard workers. They may struggle in positions where they are responsible for long-term planning, making goals and have strict schedules without help. But in jobs where they are skilled and are motivated to do the work, they can excel. Motivation can come from compensation, interest, excitement or deadlines – but the motivation needs to be sparked. Low conscientiousness people often have trouble both getting started with work, and stopping. Once they are engaged and interested, they can work tirelessly.

B) Adjustment/Stress Reactivity

‘My life was even then gloomy, ill-regulated and as solitary as that of a savage. I made friends with no one and positively avoided talking, and buried myself more and more in my hole. At work in the office I never looked at anyone, and was perfectly well aware that my companions looked upon me, not only as a queer fellow, but even looked upon me – I always fancied this – with a sort of loathing. [. . .] Of course, I hated my fellow clerks one and all, and I despised them all, yet at the same time I was, as it were, afraid of them. In fact, it happened at times that I thought more highly of them than myself. It somehow happened quite suddenly that I alternated between despising them and thinking them superior to myself.’

—Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground

Low adjustment is described both psychologically, and in general conversation, as neuroticism (Costa and McCrae, 1992; Wille et al., 2012). People with low adjustment have recurring, negative, and irrational thoughts or emotions. The lower the adjustment, the more negative and the more irrational the negative thoughts tend to be. People who have low adjustment find relatively minor challenges or stressors overwhelming. They worry what their colleagues are thinking and saying about them.

People with low adjustment worry about what they just said, what they did, and can become irrationally preoccupied with the most minor things. Low adjustment exacerbates nearly all negative reactions and mitigates positive emotions. In a meta-analysis Barrick et al. (2003) found higher adjustment was associated with improved performance and better teamwork in many occupations. Wille et al. (2012), in a 15 year longitudinal study of final-year undergraduate students, found conscientiousness was significantly associated with higher employability and lower work-family conflict.

People with very low adjustment also tend to be self-conscious, jealous and envious. This is especially pertinent at work, because being self-conscious about one’s own work can make it difficult to submit work, and can lead to work-avoidant behaviour because of concern with the perceived quality and feelings of guilt. People with low adjustment are more likely to be envious of others’ success and may take colleagues success as a sign of their own poor performance.

Very low adjustment is essentially an oversensitivity to stressors; people with very low adjustment can become preoccupied with very minor mistakes, or even believe something is wrong when there is nothing wrong. These are people who interpret silence as disapproval, praise as disingenuous, and minor errors as crippling embarrassment. Extremely high reactivity to stress can be crippling when people avoid finishing work for fear of failure and spend more time worrying than working.

Conversely, people with high adjustment do not become preoccupied with negative emotions. They will not spend unnecessary time ruminating and will not be as plagued by self-doubt. This applies to all types of work, but is especially important in demanding or leadership positions. More demanding positions present more stressors which are much more difficult for people with low adjustment. Levels of adjustment can be seen as, essentially, the threshold of stressors it will take to make a person worry.

Reactivity to stress is also a foundational element of potential. High reactivity to stress means being acutely aware of stressors, and regularly experiencing negative emotions even when they are not deserved. People with low adjustment feel more intense and more frequent negative emotions in response to increasingly minor stressors. Stress is a natural response to difficult or threatening situations accompanied by adaptive physiological responses. The basic example of a stress response is to confront (fight) or avoid (flight) the source of stress. The emotional reaction helps to pinpoint the source of stress, and to initiate the reaction.

High adjustment is usually an asset, and in general (Barrick et al., 2003; Costa and McCrae, 1997) people with higher adjustment have higher performance. But average or moderately high reactivity to stress (moderately low adjustment) can be helpful when managed appropriately at work. This is because moderate stress creates moderate arousal. In the psychological sense, arousal means excitement or a response in the brain. Many high performing people use anxiety as a tool to guide their behaviour and take steps to reduce that stress.

We have known for many years that there is a curvilinear (U curve) relationship between arousal/stress and performance showing that too little or too much has a negative impact on performance compared to an optimal amount. This is at the heart of Eysenck’s theory of arousal and can be applied to a number of different psychological processes.

Figure 2.3 Eysenck’s Arousal Hypothesis

The best way to reduce worry, for many, about a deadline, is to prepare. Feeling anxious about how well a report was written? Go back and edit it. Feel like you said the wrong thing to a colleague? Follow it up, and make sure they are not unhappy. Moderate arousal (manageable stress) can be a strong motivator to address the source of stress.

Taking extra steps to mitigate the stress and channel it towards productive behaviours can be instrumental to improving performance. Of course, conscientiousness factors are involved also. People who are better at planning and organising and motivating themselves are more likely to put in careful preparation, work, and planning to mitigate their own stress. For the high reactivity, low conscientiousness people, stressful situations can be crippling: they worry, but are not organised enough to fix the problem before it escalates.

People with very low reactivity to stress feel immune to all but the most severe stressors. This means that what many people might be concerned about, or become preoccupied with, people with low stress reactivity consider but do not worry about. At the most extreme ends, the lowest stress reactivity is similar to apathy.

Again, think how this relates to conscientiousness. Someone with very high conscientiousness might perform well, and be cool under fire. Low conscientiousness with low reactivity may be very last minute, but unbothered by being late, missing deadlines, or spending all night finishing projects only days or hours before a deadline.

In extremely demanding careers, such as leadership, reactivity to stress presents an interesting, but crucial consideration. More demanding positions present more stressors, more problems and demands. And, challenging times can present unique and great challenges for people. When people appear to be able to sufficiently cope with the stressors of their current position this does not automatically mean they will be able to manage stressors piled on by a more demanding position.

C) Curiosity

‘If we do not plant knowledge when young, it will give us no shade when we are old.’

—Lord Chesterfield

Curiosity is openness to new ideas, experiences, and situations. People who have high curiosity are more receptive to ideas, thoughts, and emotions. Curiosity is related to seeking out new experiences and ideas, and willingness to test novel techniques or approaches. Curiosity has been modestly associated with attributes such as creativity and intelligence (Hogan, 2012).

There are many tests designed to measure curiosity: some are aimed at children, others at curiosity in very specific areas like engineering or people. They are very similar in that they ask people to report their fascination, intrigue and immersion in books and activities that captivate their imagination

Curiosity at work, as a High Flying Personality Trait, is focused on openness to new ideas, methods, or approaches of doing the work. Curiosity also represents adaptability and flexibility in the workplace to perform multiple tasks, explore new ideas, and continually learn. It also includes elements of reflectiveness, creativity, and innovation (Silvia et al., 2009). In the HFPI, openness focuses on this as it is manifested at work.

Judge et al. (1999) conducted an analysis from three American longitudinal studies with 530 participants and found openness was moderately associated with job satisfaction, occupational status, and extrinsic career success. Linden et al. (2010) confirmed openness was associated with improved performance and learning outcomes. Barrick et al.’s (2003) meta-analysis of personality and job performance found openness was moderately associated with training proficiency, but was less related to performance than conscientiousness or adjustment. Openness is more a growth dimension of potential than foundational.

Those with high curiosity are more likely to look for new information and be interested in training or development opportunities. Curiosity alone though is not sufficient to be successful in training. It can help people find new opportunities and be open to new opportunities, but more is required to succeed than curiosity alone.

D) Ambiguity Acceptance

‘It is, no doubt, an immense advantage to have done nothing, but one should not abuse it.’

—Antoine Rivarol

Ambiguity is a significant and enduring part of most jobs. Large groups, complex organisational structures, poor planning and guarded communication are only a few of the factors that create ambiguity. While some people cannot stand ambiguity, ‘I just hate when people send mixed messages’, others thrive in these situations and interactions.

There is a great deal of uncertainty in the business world: things are very rarely clear; there are not enough facts and details; even legal and scientific processes are rarely straightforward. Most of us would like to live in a stable, orderly, predictable, and just world. Some people seem very threatened by ambiguity and uncertainty. They take to simplifying, ordering, controlling, and rendering more secure, both the external world and the internal world. Order is imposed upon inner needs and feelings by subjugating them to rigid and simplistic external codes of conduct (rules, laws, morals, duties, obligations, etc.), thus reducing conflict and averting the anxiety that would accompany awareness of the freedom to choose among alternative modes of action. It is therefore a great advantage to be able to feel comfortable and confident making decisions in a situation which is unclear and ambiguous.

Ambiguity acceptance (frequently referred to as Tolerance of Ambiguity; ‘AT’ in the psychological literature) describes how an individual or group processes and perceives the unfamiliar, the complex, and the incongruent (Furnham and Ribchester, 1995). However, this trait on the ‘high end’ is more than just tolerating ambiguity; tolerating implies subjugation or forbearance. As a trait, high ambiguity acceptance means enjoying and thriving in ambiguous situations.

Those who are accepting of ambiguity perform well in new or uncertain situations, adapt when duties or objectives are unclear, and are able to learn in unpredictable times or environments (Furnham, 1994). McCall (1998) suggested from extensive qualitative evidence that adapting to ambiguity is an essential trait of High Flyers. Herman et al. (2010) found ambiguity tolerance involved four facets: valuing diversity, challenging perspectives, unfamiliarity, and change.

The ambiguity tolerance component of the High Flying Personality Traits incorporates the four facets of AT. Keenan and McBain (2011) found high AT reduced psychological strain in positions that involved role ambiguity. Those with higher ambiguity tolerance usually perform better in high-level leadership positions because they have to incorporate many different sources of information and make decisions based on mixed information.

There are inevitable drawbacks to being too accepting and tolerant of uncertainty. That tolerance may mean that a person does not strive enough to get clarity when it is indeed possible to achieve. Furthermore, they may be loath to suggest or impose rules, laws, and processes that bring stability to a situation. They may be overly reliant on informal networks to obtain information as well as over reliant on intuitive thinking. The danger is essentially being so tolerant of uncertainty, flexibility and change that appropriate attempts to seek clarity are ignored.

As with every other personality trait, levels of the trait may fit with different job roles. High ambiguity tolerance is useful for roles that involve large amounts of mixed information, and different unclear paths. There are some jobs where low ambiguity tolerance is helpful. People with lower ambiguity tolerance like to have clear instructions, job descriptions, tasks with specific success criteria, and tangible outcomes. Every good leader knows the value of the high-conscientiousness, low-ambiguity acceptance employee who takes a task, needs to understand the process and the outcome, and then gets it done consistently and properly.

People with low ambiguity acceptance thrive in well-defined job roles, but may struggle when they feel managers, customers, or colleagues are unclear. High level leaders may benefit from higher ambiguity tolerance because leadership positions invariably involve different accounts of the same events, varying projections of internal and external conditions and mixed information. Yet, even leadership is not that simple. Most leadership teams involve a number of different positions, from the strategic leader (usually the CEO), where high ambiguity acceptance is an asset, whereas operational leaders can make better use of lower ambiguity acceptance.

E) Courage

‘Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.’

—Winston Churchill

‘Waste no more time talking about great souls and how they should be. Become one yourself!’

—Marcus Aurelius

Courage is the capacity to consider and choose options, even when faced with negative emotions like fear, worry, or sadness. Courage is overcoming the initial instinctive or reactive response, and choosing the best option even when it is the most challenging or demanding. Hannah et al. (2007) suggests the courageous individual uses positive emotions to mitigate fear of interpersonal conflict or reprisal to confront the behaviour. Thus, the capacity to overcome negative emotions and be responsive instead of reactive is courage.

There are various types of courage:

• moral courage: to stand up against forces of corruption, dishonesty, and criminality. It often takes considerable ‘stand-alone’ or ‘whistle-blower’ courage to point out to those in power unacceptable, immoral, or illegal behaviours occurring in the work place;

• interpersonal courage: involves confronting people in various settings like bullies, passive-aggressive or under-performing individuals who can psychologically hurt people;

• physical courage: which some jobs call upon in work situations. People greatly admire the brave, honest leader prepared to stick his or her head above the parapet.

Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden and build theory of positive psychology proposes that negative emotions restrict an individual’s potential range of actions by creating overwhelming impulses to act in a certain way. Fear may create a strong drive to avoid what is evoking the fear, which then restricts the perceived range of responses. Therefore, courage can be expressed in many situations including calculated risk taking, interpersonal confrontation, problem solving, or moral fortitude. It may be difficult to discuss a performance issue with a colleague, but with courage, it can be discussed calmly and rationally (instead of avoidance or aggression).

Courage is not always about action; sometimes silence is courageous when confrontation would be counter-productive. However, all these courageous behaviours have the same underlying cognitive mechanism of broadening the range of potential responses (Norton and Weiss, 2009). They found self-report measures of courage predicted actual courageous responses in a fear-evoking situation. Unchecked fear restricts the potential range of responses, and typically leads to behaviours like avoidance or contrived ignorance.

Courage is exhibited as the willingness to confront difficult situations and solve problems in spite of adversity. Those with high courage are more likely to stand for their own values when others disagree and are more likely to persist in spite of opposition. This is not because they are obstinate, but the reverse. The courageous person has the capacity to consider every option instead of reacting immediately; they choose the option that fits with their values, the company’s objectives, or what is appropriate given the situation.

Courage interacts with situational factors and is therefore clearly a growth dimension. A work environment that allows a courageous individual to rise to challenges may lead to success and improvement. However, a work environment that does not provide opportunities for new challenges or difficulties would not bring out the potential inherent in the courageous personality trait.

The opposite, ‘low courage’, in this sense is not cowardice; it is instinctive reactivity or excessive caution. Courage interacts with other traits; conscientiousness is the prime example. Those who are highly courageous, but have very low conscientiousness may choose what they believe to be the best option, but without specific objectives or long-term planning in mind. Thus, courage without conscientiousness can appear at best to be reckless reactivity, thrill seeking and at worst to be aggression or bullying.

F) Adaptive/Healthy Competitiveness

‘If victory is to be gained, I’ll gain it!’

—Captain James Lawrence

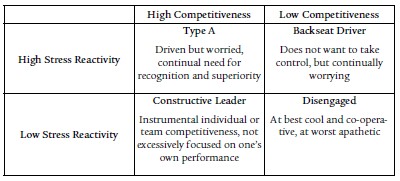

Competitiveness has been left for last, because it is the easiest to misunderstand. When we discuss our Trait Competitiveness, it means adaptive competitiveness; a drive for personal (or group) recognition, improvement, and performance. Competitiveness, in the sense of constructive competitiveness, is not about domination or aggression. Those are the most extreme cases of the traits, and many of the most problematic behaviours arise from a combination of high competitiveness and high stress reactivity.

Good competitiveness is the drive to accomplish a goal, to bring out the best in individuals, and indeed help them understand about themselves. Bad competitiveness is winning at any cost: it sneers at the outmoded negativity of the old aphorism ‘It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game.’ It is the self-aggrandisement factor associated with competition that is bad, but other (denigrating the self) improvement that is good.

Competitiveness is domain specific. Thus one may be highly competitive on the sports field, but not in the family; in the classroom, but this is not the case at work. Nearly all are competitive but some are team based and some individualistic.

Certainly, competitive individuals tend to be ambitious, achievement oriented, and dominant. But like everything else, moderation is a good thing. The hyper-competitive individual might be masking all sorts of inadequacies, yet so might the hyper-co-operative individual who is unable to make a decision, go along with, or challenge the group. Hyper-competitiveness has its down side; it is associated with poor interpersonal relations and things like road rage and accidents. On the other hand competitiveness can bring out the best in people. It can make them go that extra mile to put in that extra special effort which can bring about results.

All traits, at their extremes, cause problems. Just as excessive conscientiousness leads to perfectionism, and excessive curiosity can lead to lack of focus, extreme competitiveness can adversely affect co-operation, empathy and ethics. Figure 2.4 below shows how the two personality traits can interact to create very different types of work behaviours. It is also important to note that these are not ‘types’ in the sense of personality types, these are examples of extreme interactions, and most people are somewhere in the middle.

Figure 2.4 Interactions between Competitiveness and Stress Reactivity

Competitiveness, as a personality trait, focuses on a strong desire for individual and team success. It may be a drive to be the best leader, and knowledge that the best leader is not necessarily the most aggressive or domineering helps. Competitiveness is not just personal ambition. Trait competitiveness can be channelled into focusing on team or organisational success (Wang and Netemeyer, 2002); for example, being recognised as one of the best employers, having the greatest productivity, the highest sales, or an impressive philanthropic record.

For some personality traits, such as conscientiousness or openness, very high levels of the trait may be useful. Competitiveness has a lower threshold at which maladaptive behaviours can occur. But many high performing people find outlets for their most competitive desires, either in individual sports, video games, gambling, or competitive pet events. Indeed, the competitive can find innovative ways to make nearly anything a competition. Yet, when competitiveness is contained and channelled appropriately, then the person with high potential can focus the more constructive elements of their competitive traits towards work.

Figure 2.5 Dimensions of Potential & High Flying Personality Traits

2.5 Case Study: High Flying Exemplar

Lloyd Craig was brought into Surrey Metro Savings Credit Union in 1986 by the board when the company was on the verge of bankruptcy. It was a small, local credit union that had made a series of poor investments, and needed to bring in a leader who had the knowledge and experience to turn the company around. Under Lloyd’s leadership, Surrey Metro Savings grew from $500 million of assets to $2.7 billion in 16 years. Not only did the company grow financially, under Lloyd’s leadership the company became one of the best places to work in the country, rated fourth best employer to work for in the country, and the top financial institution to work for in Canada.

Before joining Surrey Metro Savings, Lloyd describes his experience working for the Mercantile Bank. He had various geographical assignments, but was really thrown in at the deep end, managing his own branch in California. He describes the feeling of being thrown in at the deep end in a challenging role: ‘You have to do this. You were sent down to do this – it’s just you’. And he did it. Lloyd describes that early experience that was clearly challenging, but also career-shaping. He describes this position as a key learning experience, learning to make deals, learning to manage people, and really beginning to thrive when forced to rely on his own abilities and values. His success led to a series of promotions, where he moved from managing assets to managing people – the transformation into a leader.

Lloyd’s High Flying Personality Traits show some key attributes; those attributes that change little over a lifetime. He is conscientious and courageous. When faced with challenges he plans and steps up to meet those challenges.

Figure 2.6 Case Study 1 High Flying Traits

We will discuss Lloyd’s leadership further in Chapter 12 – Strategy – but the key message is that High Flyers have the right personality, but also strong values. Success and leadership must be constructive, not destructive.

Lloyd managed a merger between Surrey Metro Savings and Coast Capital Savings in 2002, more than doubling the assets of the company. Under his leadership, Coast Capital then grew from $6 billion to $12.9 billion between 2002 and 2009. Lloyd has not just been a leader of business, but also in charitable works. He was named National Champion of Mental Health in the Private Sector by the Canadian Alliance on Mental Health in 2008. He continues to be active in charitable work even in his ‘retirement’. While he has all of the key personality traits one would expect of a High Flyer, his values suitably match.

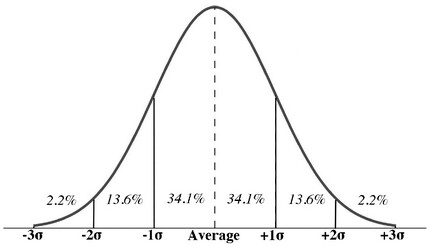

2.6 Optimality, and Too Much of a Good Thing

Abnormal is partly a statistical concept. You can be abnormally outgoing or abnormally clever. Being unusually high or low on any criterion always has consequences; the issue is now called ‘the spectrum hypothesis’. It means that extreme normality is abnormal. By definition people at extremes are rare/few, and therefore not typical. Nearly all human characteristics are normally distributed, from creativity to conscientiousness, and when tested the range of scores can be graphed and look like Figure 2.7. There are a few exceptionally conscientious perfectionists and exceptionally slovenly and disorderly individuals. Most people are fairly conscientious, slightly disorganised, but are somewhere in the middle: average.

Even factors thought to be beneficial and healthy can occur at extremes. Healthy high self-esteem becomes narcissism; out-of-the-box creative thinking becomes schizotypal; sociable, optimistic extraversion becomes impulsive hedonism. Many people believe there is a linear relationship between a ‘virtue’ and success; the more the merrier. However, it is clearly apparent that leaders can be too vigilant, too tough, and too hardworking. Selection errors occur because of linear, rather than cut-off thinking; too much of a good thing becomes a bad thing.

Nearly every human characteristic is normally distributed. Most of us (68 per cent) are within one standard deviation of the norm. Virtually all of us (97 per cent) are within two standard deviations. However very few are in the very top category, over two standard deviations above the norm. They are rare by definition: at the far extreme of the spectrum. There are usually costs, as well as benefits to extremes on either side.

Figure 2.7: Standard Deviation, Normality and Exceptionality

It seems, in general, that it is better to strive for optimality not maximality, so that one does not over-rely on strengths which then become weaknesses, hence, the idea of neither too much nor too little.

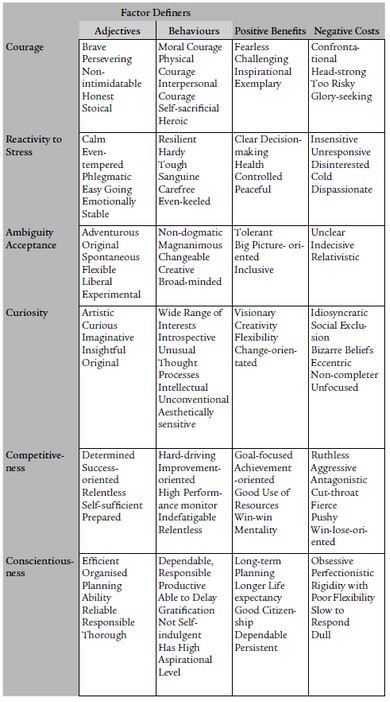

Below is our model of High Flying Personality Traits which lists both the possible strengths and weaknesses associated with each factor at one end of the spectrum.

Figure 2.8: Descriptions of High Flying Personality Traits

The central theme of the spectrum hypothesis is that extremes of any desirable trait are undesirable.

2.7 Conclusion

It is inappropriate to define High Potential exclusively in terms of a personality profile; yet personality traits do play a big part. Our review of the literature suggests that a limited number of traits are very specifically related to career success which may be thought as the building blocks of talent. See more in Chapter 4.

It should be pointed out however that it is rare to find the optimal and ideal profile and that occasionally very successful CEOs, entrepreneurs and high flying academics and scientists seem to have, at least on some of the dimensions, a very different profile.