Reuben didn’t like the looks of the weather, and this is a man who’s squinted appraisingly at plenty of threatening skies before climbing into the front seat of a floatplane. I don’t know when he started flying, but he was a working pilot in the late 1980s when he flew for another place called Iliaska Lodge. That’s when I fished there, and it’s when we must have met for the first time. When this came up over dinner one night I was surprised that I didn’t remember him, but Reuben wasn’t surprised that he didn’t remember me. To a bush pilot, fishermen are cargo; he sees hundreds in a season, and one is pretty much like the next. “And anyway,” he said, “that was a quarter century ago. We’re both older now, and our minds are shot.”

The plan was to fly to the Togiak River for the day, then out to Rainbow Camp that afternoon for an overnight and another day on the water, and then back to the lodge again in time for dinner that evening. This is one of those outfits that keeps you jumping. Every day a different river with a different guide. The pace is brisk enough that anyone who thinks of fishing as just a relaxing diversion might be happier at home in a lawn chair casting off a dock.

Flying had been sketchy all week with off-and-on rain and a low ceiling, but that morning it was really socked in, and word by radio from the camp was that it was the same or worse out there. Reuben told my friend Doug and me to suit up, pack our waterproof boat bags, and be ready to go. We’d see how things looked in an hour or so. “Remember,” he added philosophically, “it’s better to be on the ground wishing you were in the air than in the air wishing you were on the ground.”

As sometimes happens with backcountry aviation in Alaska, an hour or so stretched to all day, and Reuben finally came to get us late that afternoon. The weather still didn’t look great and we’d missed out on the Togiak, but he said if he couldn’t get through the mountains he might be able to skirt the coast of the Bering Sea out to Rainbow.

Sure enough, from the air the passes were forbidding gray walls, so we banked south to the coast and followed it over the water, where we could fly under the scud without hitting anything. It didn’t seem to be raining, but drops of water streamed up the windshield.

We were in one of the cleanest de Havilland Beaver floatplanes I’d ever seen. This thing had been fully restored, including the cabin, which is unusual. These old planes are maintained with an eye to airworthiness, but inside they often feature loose rivets, paint worn to bare metal, and seats patched with duct tape. New upholstery is all but unheard of. The camp has three of these planes, identically painted in shades of beige, brown, and green with “Bristol Bay Lodge” written in small script behind the call letters. When they’re lined up at the dock in the morning they look like the air force of a small island nation.

Reuben is the rare Alaskan bush pilot who claims not to care for these iconic aircraft. One night at dinner he mentioned that he was looking to buy his own plane, and I asked if he wanted a Beaver. Several lodges had closed during the recent Great Recession, and word was that with a glut of them on the market the prices had dropped by as much as six figures.

“God no,” Reuben said. “Beavers are about nothing but power. They’re good for getting airborne in a short distance with a heavy payload, but once they’re up there, they don’t really want to fly. You know all that fiddling I’m always doing with the controls? That’s me just tryin’ to keep the damned thing in the air.”

We were flying low over the Bering Sea. To the north I could see maybe a quarter mile up a coastal plain veiled in clouds. I knew the mountains we’d originally planned to fly through weren’t too far inland, but I couldn’t see them. Below us were bare rocks covered with gulls and cormorants and choppy gray salt water that looked very cold. Reuben was busy fiddling with the controls. Keeping the damned thing in the air seemed like a real good plan.

We landed on a pond that looked about the size of a mud puddle from the air—exactly the kind of place a Beaver was made for. Doug and I piled out along with some fresh supplies for the camp. The old sports piled in along with an outboard motor that needed fixing. There were first impressions and quick handshakes all around. Dave, the cook, was a short, wide man with a black beard and a hint of Georgia drawl: good news for those who believe you should never eat at a place with a skinny cook. The guides, Tyler and Matt, were loose-limbed, bearded, scruffy, and young, with exposed skin like leather. A month later I’d show a friend a photo of the three of us cradling a salmon I’d caught, and instead of complimenting me on the size and condition of the fish, he’d say, “Jeez, where’d you find those hippies?”

Reuben was back in the air in ten minutes, not wanting to dawdle in case the weather turned for the worse.

Before long we were in a johnboat motoring upstream to the confluence of the Negukthlik and Ungalikthluk Rivers, which the guides had understandably renamed Rainbow and Wrong Way. This was a quick errand before supper. We simply motored to a long pool where Matt and Tyler knew chum salmon would be rolling and caught a few. These were hard, muscular fish, but like all Pacific salmon they were there to spawn once and then die, and as soon as they hit fresh water they would begin to sour. They were silver when they had entered the river, but even close enough to the sea that you could smell salt in the air they were beginning to color up in dripping wax patterns of sickly greens and purples. Several years ago there was a move afoot to change the name of this fish to calico salmon, because it was thought that would sound more appealing to tourists than chum or “dog” salmon, as they’re sometimes called. It never caught on.

As we neared camp on the way back, Matt’s German shepherd, Kaiser, trotted down to the river and playfully hid behind the single tuft of tall grass on the bank with his ears clearly showing. The joke here was that when we walked past he didn’t jump out at us, which is typical of this breed’s dry sense of humor. You could say Kaiser was the camp’s early bear warning system and not be wrong, but most days he was just uncomplicated company.

The camp was a collection of tents and tan-colored WeatherPorts (picture a cross between a wall tent and a Quonset hut). There was no light in the cook tent except for what little seeped through the canvas walls and the two small, translucent windows. A lantern would have required kerosene and a lightbulb would have burned gas in the generator, and there was no real reason to waste either. Even batteries for headlamps don’t exactly grow on trees out here. Before my eyes got accustomed to it, I stepped on Kaiser, who is mostly black and continually underfoot.

Dinner was grilled king salmon and a Cajun rice dish with peas. Dave turned out to be one of those cooks who could do a lot with the little he had to work with, using a light touch and spices he’d brought from home. I’ve been introduced to any number of so-called chefs at fishing camps who turned out to be passable short-order cooks at best, but Dave was the opposite: a trained chef who was feeding fishermen in the Alaskan bush for private reasons while incessantly listening to Frank Sinatra on his iPod. Tyler said his girlfriend back home had suggested he lose a few pounds over the summer, but he hadn’t been able to manage it. He shot Dave a look that seemed to fall halfway between blame and affection.

It didn’t take a lot of imagination to see how things would go out here. These guys were in camp for months, and the interminable Arctic summer daylight would make time stand still. Days would revolve around meals and the daily weather call from the lodge to see about flying conditions: a mundane chore on which lives could conceivably depend. Wind speed would be an educated guess, but you’d get good at it with practice. Wind direction was easy, since the river was a compass needle running roughly north and south. There was a distinctly shaped four-hundred-foot-high hill a mile or so upstream, and how much of it you could see—if you could see it at all—would give you visibility and ceiling. If you were far wrong about any of this, none of the pilots would be shy about bringing it up.

Fishermen would arrive in twos and threes on a more or less regular rotation, adjusted for visual flight rules and the vicissitudes of weather. Dave would feed them, and in their excited preoccupation only a few would realize how good the food was. Tyler and Matt would try to get them into fish, answer their questions, point out sights that weren’t always obvious in a barren landscape, and generally pretend that this was all just some people going fishing together instead of the job it was most days.

There’d be the whole range of people, from return clients who knew the score to fish counters with wild expectations to the couple who thought, Last year we toured wineries; this year let’s go to Alaska and learn to fly-fish. And there’d be the inevitable dim bulbs. Tyler said one day he told a fisherman to mend his line upstream, and the guy asked, “Which direction is upstream?” There are infinite possible answers here, but the correct one is, “That would be to your left, sir.”

Why people do this kind of work is an open question, and the answer is not the same for everyone. It’s for the money in the strict sense that you wouldn’t do it if they didn’t pay you, but it’s no surprise that the most authentic lives rarely pay off in terms of big bucks. Some are young and starry-eyed about life in the backcountry; others are older and realize that while your twenties and thirties can be about reinventing yourself, your forties and beyond are more about trying to make the best of who you’ve become.

Many of the people you meet in Alaska during the fishing season have entirely separate and sometimes vastly different lives elsewhere. That’s a compelling idea—sort of like having a secret identity—but there can be reentry problems. A guide at Bristol Bay told me that when he goes home to his wife and daughter in the Midwest at the end of the season, he pussyfoots around for a while, acting more like a polite houseguest than a returning dad. It’s not that his family isn’t delighted to see him; it’s just that while he’s had his separate life, so have they, and they’ll now have to get used to his presence the same way they got used to his absence months earlier.

The next morning the dusky light through what was beginning to seem like a perpetual overcast was exactly the same as it had been when I went to bed, and I had the sense that I’d only been down for a ten-minute nap. The only thing that was different was the river, which had swollen to three times its previous width and was now flowing in the opposite direction, accompanied by at least one seal. This tidal surge explained the enormous mud hook of an anchor in the johnboat that I’d thought was overkill when I tripped over it the day before. (First the anchor and then Kaiser; for some reason I was tripping over things.) It was raining just hard enough for me to put up the hood on my rain jacket. I got a cup of coffee from the cook tent and watched a bald eagle and two herring gulls loudly squabbling over a dead salmon until Dave called us for breakfast.

We motored through the rolling chums in the confluence pool and headed up the left fork looking for king salmon. It was late in the run and most of the fish would already be far upstream on the spawning beds, but some of the biggest kings like to sidle in fashionably late for the party, as if they don’t want to betray their eagerness. It seemed worth a shot.

A lifetime of fishing runs through your mind when you look at new water. At first glance this could have been a small prairie river in the Mountain West, but it wasn’t. If there were fish here at all—and there may not have been—they wouldn’t be resident trout tucked against the banks or nosed into the riffles sipping mayflies. These would be ocean fish passing through on their final errand, and they’d be resting in the deep guts of the pools, sometimes unseen, other times rolling restlessly the way a dozing cat swishes its tail.

We worked half a dozen pools that all looked fishy and that had produced kings during the height of the run, snaking our hamster-sized flies on sink-tip lines into the depths where, we imagined, the salmon would only have to open their mouths. The weather was gray and borderline foul. The four-inch-long hot-pink-and-electric-blue Intruder fly Matt had given me was as gaudy and lively in the water as an alarmed squid. Everything seemed right. Lunchtime came and went. The confluence pool full of eager chums crossed my mind, but I wasn’t about to succumb to temptation unless someone else mentioned it first, and maybe not even then. Above all else, a salmon fisherman is resolute—or so he tells himself.

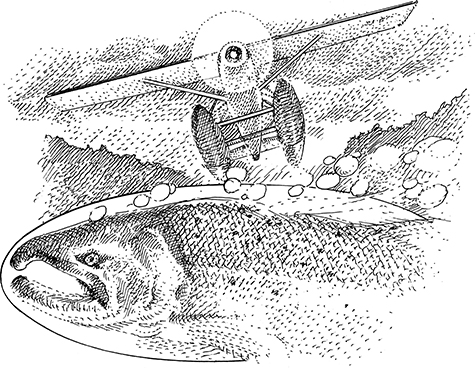

It was late afternoon when I hooked a king in a trouty-looking pool with a defunct beaver hutch on the far bank. When I first set up, it felt as solid and unmovable as the sunken stump Matt had told me to watch out for in here, and for a split second my heart sank, but then the fish turned and ran.

King salmon are appallingly strong. It sounds overwrought to say that you can feel the ocean in a hooked salmon, but there’s no other way to put it. When you hook a big one, all you can really do at first is hang on and trust that your knots won’t fail and your reel won’t seize up. The fish has your complete attention, and you believe you’ll remember every second of the fight with unnatural clarity, right down to the pewter-colored sky and the cool drizzle on the backs of your hands. But memory survives as a series of snapshots, some of which get misplaced, so although I still clearly remember the fish in the net, I’m now no longer sure how it got there.

The fish turned out to be a dime-bright hen built like a little oil drum that had come back from years at sea well fed and without so much as a seal bite or a net scar. I was actually proud of her for having done so well for herself. We didn’t have a scale, but Matt guessed the weight at thirty-two or thirty-three pounds. Tyler pointed out the sea lice around her anal fin and said, “This girl probably came in on the tide about the time we were having breakfast this morning.” What a thought! I remembered a friend saying, “If it don’t got salt water in its veins, it ain’t a salmon,” which pretty much says it all.

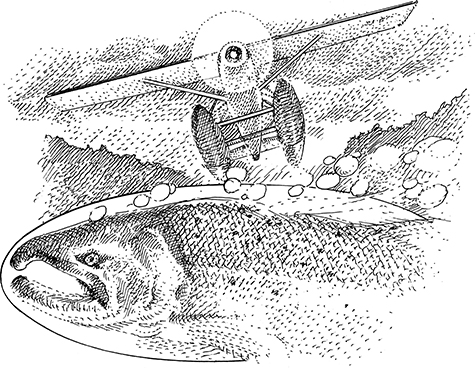

We’d seen some other fish rolling in this pool, and a few minutes later Doug was into one that took in deep water, turned at the surface in a fluid, silvery boil, and ran downstream, peeling off backing at an alarming rate. We followed in the boat until the fish wallowed briefly in a pool, and then followed on foot when it rolled and ran again. This was a strong, heavy fish, and even after a long fight covering an eighth of a mile of river, it bulldogged at the end. Doug didn’t rush it, and Tyler stood poised with the long-handled net, waiting for his moment, both understanding that a wrong move here could blow the whole deal.

This was another bright hen in mint condition, almost a twin of mine, but noticeably heavier at thirty-five or thirty-six pounds. In the net it could have been mistaken for the chrome bumper off a 1952 Buick. Doug is a lifelong fisherman and a cool customer with a sly sense of irony. He’s in the movie business now—a partner in the Fly Fishing Film Tour—but he started out as a numbers guy, and once told me he’d gone into accounting only for the glamour and the groupies. He’d played the fish calmly and patiently, with no visible sign of panic, but when he finally cradled this slab of a salmon all he could croak out was, “Holy crap!” Then his mouth continued to open and close rhythmically like a fish out of water, but nothing came out. This was his first time in Alaska and his first king salmon. It was also the only time I’ve ever seen him speechless.

I whipped out my digital camera for the hero shot to show the folks back home, but the battery was dead. No problem. Tyler dug his out, but it was dead, too. So was Matt’s. What the fuck? Was there a mother ship hovering above us in the cloud cover, sending us back to the Stone Age with an electromagnetic pulse?

Doug’s camera may have held a charge, but it was in the boat, which was out of sight around the bend upstream, and the fish was already getting her strength back. She’d be ready for release before anyone could run back and get it.

The four of us stood there with current whispering around our waders, reminding ourselves that the salmon is not the photo of the salmon, which will never quite stand up to the living memory anyway. The salmon is the salmon itself, here and gone so fleetingly that half an hour later you’ll wonder if it was even real.