A friend called from Texas. He said he was standing at the crest of a low, bare hill where he’d walked with his second cup of morning coffee to take in the view and get a cell phone signal. He’d driven down there from his place in western Colorado to deliver some horses, and he was happy for the work and happy for the change in weather five hundred miles to the south. “When your livelihood depends on horses,” he said, “your two choices of working conditions are dust and mud, and after a couple of weeks of mud, dust starts to look pretty damned good.”

Then he asked if I’d been getting out, meaning getting out fishing.

At my dentist’s office I showed off a snapshot of a large king salmon I’d caught in Alaska since I’d seen him last, and in response he whipped out a photo of a twenty-three-inch brown trout he’d caught in the Madison River the previous fall. It was a fat, buttery-colored male with the kind of grotesque kype that makes non-fishermen ask, “What’s wrong with his face?” The dentist’s assistant stood by smiling patiently. I assumed she thought this was charming—or at least harmless.

At the post office another friend said that a few days earlier he’d been casting on the liquid end of a half-frozen reservoir nearby, hoping for nothing more than a few holdover stocked rainbows, when he hooked and landed an eight-pound lake trout, which around here is a pretty nice one. He said, “That’s probably the biggest fish I’ll catch this season, so it’s all downhill from here,” but he didn’t really believe that. In fact, any fisherman would believe just the opposite.

So it was in the air.

The common redpolls that had shown up back in early winter were still hanging around the bird feeder when I heard my first red-winged blackbird. This was on a snowy, fifteen-degree morning, and the cheerful, summertime call sounded impossibly foreign, as if I’d just heard a toucan. I looked around for the blackbird, but all I could see were the ubiquitous juncos looking like little executioners in their black hoods. It seemed way too early for red-wings, and I wondered if I’d actually heard it after all. Maybe it was wishful thinking.

I had been getting out, though, mostly to a tailwater two and a half hours south. There was a time when I’d have said I knew this river well and I’d have been right, but since the 1970s it’s gone through some kind of paroxysm every decade or so on average, after which it reinvents itself, after which I try to relearn it. Whirling disease, wildfires, flash floods, you name it. I once thought that if I fished this river for four decades, I’d know it inside out. It never occurred to me then that my hard-earned knowledge would expire like a driver’s license every ten years.

Most recently, siltation from floods has turned the once-rocky riverbed into shifting aquatic sand dunes, and it’s become more of a caddis river than the mayfly stream I was once so familiar with. So I make a habit of stopping at the local fly shop to ask the owner what the hot pattern is that week. At least, I used to ask the owner, before he started to show signs of the occupational disease known as “the red ass” and began staying home, leaving the shop to one of the off-duty guides. Never mind; the advice and the flies are still good, and my fly box continues to bristle with unfamiliar patterns.

One day I fished the river for hours without a bump—sticking it out as a matter of principle—before I found a little pod of risers and hooked and landed three trout in what turned out to be my last fifteen minutes on the water. I could see that the fish were coming to the surface, but I couldn’t tell what they were eating and didn’t dare wade close enough for a better look in the low, clear water. It was late in the day, and I understood this was my one fleeting shot, so I tried a nondescript size-22 parachute midge and it worked. Good thing, because the rise shut off like that, and I wouldn’t have had time to stand around changing flies. After releasing the third trout I stopped to chip some frost from the guides, then looked back at the water and the fish were gone.

Another time I pounded the river all day with nymphs and caught only one fish, but it was a twenty-one-inch rainbow. This was one of those slow winter days when there was no reason to fish before ten in the morning or much after three in the afternoon, so I’d spent the same amount of time behind the wheel as I had on the water. I guess I was vaguely aware of the five-hour round-trip drive, the tank of gas I’d burned, and the day’s worth of lost work in return for a single trout, but then, a wise fisherman never actually does the math.

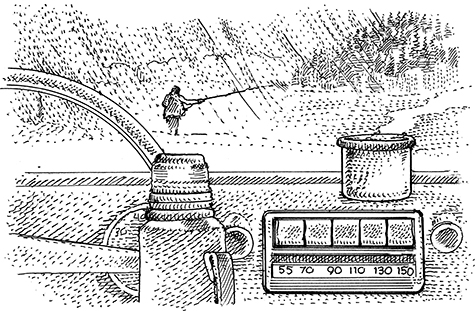

We do have the advantage here in Colorado of having no closed fishing season, so you can be out with a fly rod any day you can find open water. At least I think that’s an advantage. Some fly-fishers—maybe the smart ones—wait for the fishing to pick up with the pre-runoff hatches in April and May and spend what’s left of winter on the usual grown-up obligations. But others fall victim to the circular logic stating that not going fishing on a day when you could have ruins you for anything else, so you might just as well go. There were days when I stopped to fill my Thermos on the way to the river and Mindy down at the coffee shop glanced out at the weather and asked, “You’re going today?” Sometimes this made me feel like one crazy-tough hombre; other times I wondered why I hadn’t slept in.

Of course, for much of the winter you’re relegated to the tailwaters, because they’re the only streams that aren’t frozen. Tailwaters are what Thomas McGuane called “the great theme parks of American fly-fishing,” with their more or less stable water temperatures and artificially inflated populations of insects and fish. They’re irresistible for all kinds of reasons, but all those trout breed the peculiarly postmodern sense that anything short of a twenty-fish day is a bust, so when things are slow there’s the temptation to lie about numbers or to vaguely allow that you’re “getting your share.”

Some fishermen get proprietary about these honey holes and consult websites daily to check on their wildly fluctuating stream flows. In these unenlightened times, dam releases have more to do with toilets flushing in the suburbs than with trout habitat, and this sad state of affairs can push some people up against the wall. Some years ago there was a rumor going around that the water board was bumping the spring flows on a local tailwater with an eye to keeping the rainbows from spawning. (Kill off the trout, this conspiracy theory went, and we won’t have those pesky fly-fishermen looking over our shoulders anymore.) It sounded far-fetched, but after Watergate, Iran-Contra, Bush v. Gore, and NSA spying, anything now seems possible.

For a change of scene, some friends and I made the first trip of the new year to a favorite prairie lake. I left home before first light that morning and drove down the valley toward the state highway, squinting ahead into my high beams looking for the deer and elk that can pop out of the darkness like targets at a shooting gallery. I had a cup of coffee strong enough to wake the dead, but it hadn’t taken effect yet, and I was cold and still ached for sleep. This has always been my dirty little secret: I love being up and out before dawn, but I hate like hell to get out of bed.

We were hoping for a half moon of open water to fish, but found the lake completely ice-free except for a fragile morning glaze around the shore. This lake is spring-fed, so the ice stays thin anyway, and a few days of halfhearted sun and a steady breeze had done the trick. We got there right at dawn, and although the air wasn’t above freezing, there were already a few trout rising to midges. Could these tiny, delicate insects actually emerge and fly away when it was so cold? Probably not, which would explain why the fish were rolling with such lazy confidence to prey that couldn’t possibly escape. We rigged up quickly, then sipped more coffee and warmed the sting out of our fingers before we started casting.

We’d timed this trip to slip in ahead of an approaching front to take advantage of the falling barometer that’s supposed to make trout want to “eat everything in sight,” as a friend who’s prone to hyperbole says. I’ve never found that to be literally true, but trout do seem to like the cloudy skies that come with low pressure, and of course there’s the self-fulfilling prophecy that allows you to do 70 percent of your fishing on a falling barometer, catch 70 percent of your fish, and conclude that it obviously works.

The front first showed itself as a dishwater-colored cloudbank oozing down from the Continental Divide and a nearly imperceptible, possibly imaginary lightening of the atmosphere. Trout rose steadily to midges—because of the falling barometric pressure or just because the bugs were there and the fish were hungry—and we hooked and landed some of the chunky rainbows this lake is known for.

It wasn’t until midafternoon that a gauze curtain of sleet started up the valley from the northwest. It hung there, two miles out, long enough for us to think maybe it was just a squall blowing by to the east, but then the breeze kicked up a notch and I began to feel cold pinpricks on the back of my neck. I hooked and landed a trout then that took my full attention for a few minutes, and the next time I looked, the silhouette of the foothills had vanished behind an opaque and utterly impersonal bank of sleet. The wind had clocked around so it was blowing straight down from the north, and it brought frozen drops hard enough that it was difficult to look right into it. Rocky Mountain weather is as dramatic as the landscape, but some storms seem particularly emphatic, and this looked like one that was capable of sustained seriousness. I considered the shelter of the pickup parked a quarter mile away and wondered how wet the bentonite of the two-track leading out of the valley would have to get before it became impassable even in four-wheel drive.

We zipped up our rain slickers and cast to trout rising in the narrow slick along the windward shore. By “cast” I mean we let our lines furl out in the wind until they straightened, and then placed the fly on the surface by lowering the rod tip. We got a few more trout on midges, but pretty soon it was pointless, and by five o’clock we were sitting in a Mexican restaurant in town. This was one of those joints where your enchiladas arrive so quickly you have to suspect frozen portions and a microwave, but after a cold day on the water you’re too hungry to care.

Forty-eight hours later there was two feet of immaculate snow on the ground at the lower elevations and more than twice that amount in the high country to the west. And it was that dense, heavy, springlike stuff that turns shrubs into moguls, builds precarious white hats on fence posts, and makes a snow shovel heavier than you care to lift too many times in a row. In Minnesota, where I grew up, they called this “heart-attack snow” because every winter it would spell the end for any number of elderly midwesterners. They’d trek out to shovel their driveways at age eighty-nine to avoid paying the neighbor kid a dollar and come back feetfirst. At the funerals people would say, “Wasn’t that just like Bill?”

After the front moved through, I drove to the fly shop, where the storm had folks talking about the coming spring runoff. In just a few days the snowpack had gone from 77 percent of average (more than a little on the dry side) to 90 percent statewide and slightly over 100 percent in two of the eight major drainages. There were still half a dozen different ways the snow situation could turn out by spring, but one possibility was a normal spate followed by a perfect season, and that’s the prediction everyone had settled on. The optimism at the shop was so palpable that I bought fresh tippet material—4X through 7X—and diligently wrote the date of purchase on each spool. I have a pathological fear of old tippet and live in terror that I’ll break off a good fish because my 6X monofilament has gotten brittle with age.

Still, winter was beginning to wear thin for me. This didn’t rise to the level of an existential crisis—it’s just that back in the fall the first fires in the woodstove had been items of manly self-reliance, while five months later I was tired of carrying in armloads of wood. I still had the fishing duffel packed with a down jacket, a wool sweater, and the hat with fuzzy earflaps that makes me look like Elmer Fudd, but my private vision of fly-fishing was now tending more toward warm summer evenings and wet wading in vacant mountain creeks. On the other hand, the rest of the winter fishing was still there to do, and it would be a shame not to do it.

Everyone has his own take on this situation, and it’s usually an unspoken assumption dating to childhood. For many in my generation, fishing and hunting were understood at a cultural level almost from birth, but they were rarely discussed except in practical terms. My uncle Leonard was a fisherman first and a hunter second, while Dad was a hunter who only fished between hunting seasons. But each of them thought you should be skilled at both; Dad as a matter of style and self-respect, Leonard as a way to avoid wasting bait and ammunition.

At an early age I could recite my favorite lures—the Daredevle, the Johnson Silver Minnow, and the Hula Popper—and I owned a shotgun and a rifle long before I traded my Schwinn for a Ford, but if you’d asked why I wanted to fish in the first place, I’d have been stumped. The stated goal of fishing and hunting was to bring home the bass, pike, bluegills, pheasants, and grouse that tasted so much better than anything Mom bought at the store, but there was also some other unspoken element to it. There was the aura of work about it, but there was none of the preening and posturing you now see from extreme-sport types. This was just a thing people did, and some things were harder than others. Of course, in those days I was mostly out with men who had recently saved the world for democracy in World War Two. These guys treated everything like a job and had a somewhat cavalier attitude about discomfort that boiled down to “Well, at least no one’s shooting at us.”

I remember ice fishing. It was a miserable business before the advent of power augers and heated shanties, when you spudded your hole by hand and sat out in the weather on an overturned bucket. I always suffered more from the cold than the grown-ups because I was deemed too young for the regular nips of peppermint schnapps that kept them either toasty or oblivious. Sometimes they brought me a Thermos of hot chocolate or, later, coffee, but an hour from the truck it would be lukewarm at best. I went because the grown-ups went, and I’d reached that point in life when I couldn’t stand to be thought of as a boy for even one more day. It was always satisfying to bring home a stringer of delicious cold-water perch that had frozen into tortured postures in their death throes out on the ice, but I much preferred casting to lily pads in warm weather, although even in summer the fishing could be made hellish by mosquitoes and blackflies. Some days “trying a different spot” was just an excuse to start the outboard and outrun the bugs.

I especially remember going goose hunting for the first time. We walked out into snowy corn stubble with flashlights in a frigid predawn, picked our way through an elaborate set of silhouette decoys, and climbed into a five-foot-deep pit in the ground. I sat there shivering, breathing that fresh-grave smell, and thinking, This is what it’s like to be dead. But an hour later I’d killed two geese with a shotgun that was once owned by my grandfather and felt like the kind of guy they’d someday write folk songs about.

On the way back from the fly shop I stopped at the hardware store for lightbulbs and batteries. I must have said something to set off the owner, because he launched into his stock lecture about the creepy intrusiveness of government, but then he seemed to remember how many times I’d heard this before, cut it short, and asked, “So, you been fishing?”

At home I read an e-mail from a friend who was holed up somewhere near Great Smoky Mountains National Park. He’d left a job in Florida and was fishing his way in the general direction of Michigan, following the retreat of winter north along the Appalachians in no particular hurry.

He said he’d caught some trout, broken a rod tip on a rhododendron bush, patched his waders with bathroom caulk and duct tape, and so on: a more or less typical report from a traveling fisherman. But eventually he’d gotten ahead of the weather and was currently waiting out a cold spell in a town where he’d found friends to party with and a barista who brewed coffee to his unusually high standards.

He wrote, “Coffee is one true friend, and a friend shared by many. It transcends language. Coffee, music, and fishing are transcendent. That’s my short list.”