It was the kind of bone-dry, ninety-eight-degree day that makes the enameled blue Colorado sky feel like an anvil on your head. It hadn’t rained in a month and everything was wilted, from the junipers and cottonwoods along the gulch to the sleeping cats draped over the porch railing like dishrags. And taking up most of the northern horizon was the immense plume of gray smoke from the High Park fire with slurry bombers swarming it like flies.

I was packed for a fishing trip and was wondering whether I should cancel. Things do tend to go south when I’m away from home, as if my little world were held together only by the force of my presence. There have been blizzards, floods, hurricane-force Chinook winds, downed trees, troublesome bears, power outages, plugged toilets, you name it, while I’ve been gone. Susan once asked, “Why is it that you’re always off fishing when the shit hits the fan?”

Once there was even a fire. I came home from British Columbia to find a twenty-acre fan-shaped burn mark stretching from the floor of the valley to the natural firebreak of rim rock at the top of the ridge. I heard the whole story—the idiot neighbor who started it; the run-in between residents ineptly fighting the fire and the Forest Service crew—but by the time I got home the excitement was long since over and things were back to normal.

Wildfires are a natural feature of Colorado’s ecosystem, and as long as we’ve lived in this valley I can’t remember a summer when we couldn’t see and sometimes smell the smoke—and once the actual flames—from one fire or another. Everyone we know has an evacuation plan stuck to their refrigerator, including a detailed list of items to take. Fire causes people to lose sight of what’s useful, and there are stories of otherwise rational folks fleeing their homes with nothing but a handful of steak knives and a duck decoy.

And High Park was a nasty one: forty-six thousand acres at the time and spreading by the hour. It was 10 percent contained (or 90 percent uncontained), and the hot, dry conditions had turned the woods to kindling. More to the point, it was only twenty miles north of the house. A firefighter friend said he couldn’t imagine even a big one burning that far at right angles to a prevailing westerly wind, but then carefully added that he wasn’t offering a guarantee.

I asked Susan if she thought I should stay home, and she said no. In the twenty-three years we’ve lived together, she has never so much as hinted that I not go fishing (a working definition of “true love”), but she did ask me to get my stuff together in case things changed and she had to evacuate.

It didn’t take long. There were the usual bankbooks, insurance policies, and other important papers, a stack of fly rods, a milk crate full of reels and fly boxes, and a framed photo of my late father taken when he was a tail gunner during World War Two. It was absolutely everything I would need to start over, and it made a disappointingly unimpressive little pile. The next morning I drove to the airport and flew to Maine.

I met Carter Davidson at the baggage claim and we drove north toward Bethel, Maine, and the Androscoggin River, where we would rendezvous with my writer and editor friend Jim Babb and Carter’s guide friend Rick Estes. The weather out east had also been in the nineties, but by the time I got there the hot spell had broken, with low clouds, rain, and highs in the sixties. I can’t tell you how good it felt to zip up a fleece vest after weeks of Colorado’s apocalyptic heat wave. It does get really warm in the American Southwest and you learn to live with it, but when it’s too hot for too long I begin to act like an old pickup I used to own that would stall, vapor lock, and refuse to restart until it cooled off.

I know Carter as a documentary filmmaker and fishing guide: two professions that have bred the kind of inventive optimism that lets him regularly make something worthwhile out of things as they are. We stopped on the way to the river to pick up his drift boat at a friend’s house. It was a handsome wooden dory that he’d built a few winters earlier, and as we trailered it up he pointed out some flaws in its construction that only the builder would see. This is akin to saving a life with a delicate operation and then, because you’re a perfectionist, apologizing because the stitches closing the incision could have been straighter.

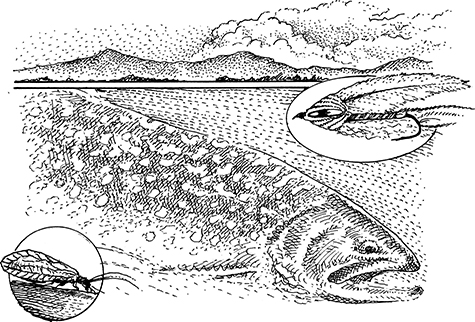

The Androscoggin is a big, mostly placid river surrounded by the kind of lush, juicy forest that in my current state of mind struck me as almost fireproof. The first day out we drifted into a mating flight of alderflies. They looked like beige snow swirling in the crowns of the black spruce trees before they dropped down to the surface to lay their eggs and get eaten by trout. We anchored out and caught some fat little browns and rainbows, but the one bigger trout rising off by himself refused everything I threw at him and finally went away. I told myself it was an impossible drift.

The next day was dark and rainy and the river farther downstream seemed dead until we started to pick up fish in a bankside run below a tributary stream. These were the same sort of stocky, workmanlike trout, and it seemed as though every fish within a mile of river was crammed into this narrow seam. Jim and I landed a dozen each on small wet flies before we began to suspect an unfair advantage, so we beached the boat and took some water temperatures. The river had warmed up during the recent hot spell, and even with the cooler weather it was still near seventy degrees, while the creek was closer to sixty. Those trout had crowded into the mouth of that stream trying to cool off.

Later that day we fished through an hour-long downpour that may have chilled the water a few degrees, and Jim landed two big rainbows on nymphs in a hundred yards of river while I somehow stumbled onto the perfect drift for chubs.

The next day Jim, Carter, and I would be driving to the Rapid River, where there was no landline or cell phone reception, so that evening I called home to check on things. The temperature in Colorado that day had hit 102 degrees with a humidity of 7 percent. The High Park fire had grown to fifty-four thousand acres—still mostly out of control—and the evacuation center near the town of Laporte had itself been evacuated because of smoke.

“What’s it like there?” Susan asked.

“It’s raining and in the fifties,” I said, not quite managing to sound matter-of-fact. I was trying to muster at least a mild case of survivor’s guilt, but was overcome by selfish animal comfort.

“I’ll bet that feels good,” she said.

“Yes, it does,” I admitted.

The Rapid River owes its fame to two women. One was Louise Dickinson Rich, author of dozens of books but best known for her 1942 bestseller We Took to the Woods, which introduced America to the laconic rural Mainer many think of as a stock fictional character until they meet one in the flesh. The other was Carrie Stevens, the milliner turned flytier who invented no fewer than twenty now-classic streamer patterns, including the beautiful Gray Ghost that has survived ninety years of changing fashions better than blue jeans. The Rapid also happens to be one of the last rivers in Maine where you can catch a five-pound brook trout—which doesn’t mean you will.

We splashed a mile or so up a dirt road full of puddles to Rich’s old summer house and walked around to the kitchen door to check in with Aldro French, who now runs the place as a combination historic site and fish camp. French is a large, barrel-chested man with a shock of white hair that hangs down to his shoulders. On a chilly day he wore a faded sweatshirt with the sleeves cut off, shorts, and flip-flops. He was the type who could be either younger or older than he looks, although something in his manner makes you suspect older.

French ushered us into the big, cluttered New England kitchen, served us stunningly strong warmed-over coffee, and delivered a monologue that went from martinis to Mount Rushmore to coffee cups to salmon fishing to crank telephones to dogs to magazines and so on without the benefit of transition. Later Jim suggested that the man might be a little “woods queer”: an old Maine term for those who have grown peculiar from spending too much time alone in the bush. When the subject of Louise Dickinson Rich pilgrims came up, French said, “In fact, I got a bunch of old ladies coming in tomorrow.” Then he added, apparently to himself, “Hell, at my age I don’t know who I can call an ‘old lady’ anymore.” Later Jim said that a common symptom of woods queerness is doing your stream-of-consciousness thinking out loud.

We started at Lower Dam, where the old log sluices and stone riprap churned the river into incomprehensible currents. Jim and I spread out along the near bank fishing dry flies in the braided pocket water. Carter had perched on a rock where he could reach a main current tongue with a streamer. Farther out, some fishermen had climbed down the aprons of the dam to swing streamers as fishermen have done since Carrie Stevens fished the prototype of the Gray Ghost on the Rapid and caught the six-pound, thirteen-ounce brook trout that came in second in the 1924 Field & Stream fishing contest.

The story goes that the first Gray Ghost was plain and simple—just white bucktail and dun saddles on a bare hook—but Stevens, who knew about exotic feathers from making ladies’ hats and about fishermen from living in Maine, later prettied it up with orange silk floss, silver tinsel, peacock herl, silver pheasant, and jungle cock to make it more saleable, thereby inventing what we now know as the New England–style streamer.

The rest is the history some fly-fishers no longer seem all that interested in, although to others the angling past, with its big fish, fancy flies, and dowdy characters, is still surrounded by an amber glow, as if it were backlit by kerosene lamps. Things really were different then. Carrie Stevens was married to a guide and she did fish, but she wasn’t what some bloggers would now call a “chick in waders.” In the black-and-white photos I’ve seen, she’s in a proper dress and pearls and looks like your grandma on her way to church.

The Rapid’s legendary big brook trout were scarce that day—it hasn’t been like the 1920s since the 1920s—but we got a few chubby little ones as well as some landlocked salmon that were as exotic to me as peacock bass. You couldn’t ask for more from a game fish than you get from a landlocked salmon. They’re bright and pretty, they feed freely without being pushovers, and once hooked, they spend as much time in the air as in the water. They’re like bonefish in that you never get past thinking they should be bigger than they turn out to be based on the fight they put up. Jim got one below the ruined pilings of Middle Dam that, before it was all over, had tangled his two-nymph-and-indicator rig beyond repair and tied an overhand knot in his fly line.

A few days later at Bosebuck Mountain Camps, I was introduced to the owners, Mike and Wendy Yates. When Wendy learned I was from Colorado, she said she’d just heard on the radio that a big fire out there had blown up and there were a bunch of fresh evacuations. I asked where, but she didn’t remember. There was no cell phone reception there, either, so she let me call home on their landline.

Susan said High Park had grown past eighty thousand acres but was now burning northwest, away from the house and into largely uninhabited state forest along the Cache la Poudre River. The fire that had made the national news was Waldo Canyon, a new one a hundred miles to the south. Our friends Ed and Jana were among those who’d been evacuated from Manitou Springs, and the last Susan heard, they’d gotten out okay and were on their way to stay with friends. No word since then.

“What’s it like there?” I asked.

“Hot. In the hundreds. And smoky.”

She didn’t ask what it was like in Maine, and I didn’t volunteer that the rain had stopped, the skies had cleared, and it was warming up. Midseventies with a pleasant breeze was not what she’d consider “warm.” I was still on the phone when Wendy came back in and gave me a questioning look. When I answered with a thumbs-up, she flashed me a smile I can only describe as genuine.

The only rule I was aware of at the lodge was that you showed up on time when the bell rang for dinner, and that evening everyone did. I could see that Wendy was the kind of small, good-natured woman whom men instinctively obey on the rare occasions when she puts her foot down.

The dining room was café-sized and pine-paneled, with plank tables and plain, straight-backed chairs. Along one wall was a line of mounted white-tailed deer heads looking as solemn as Supreme Court justices. The place was less than half full because the good spring fishing was winding down into the hot, buggy summer, and they wouldn’t see crowds of fishermen again till fall. Soon the cabins would begin to fill up with family vacationers, which Mike wasn’t looking forward to. They were fine for the most part, he said, but after a few days they’d run short on activities and begin to find things for him to fix: a sticking door, a loose porch step, a rattling doorknob. Mike preferred fishermen, at least partly because they were gone all day.

We met up with Rick Estes again (he guides at the lodge) and fished the Magalloway. This is a pretty, tea-colored river flowing through mixed coniferous and deciduous woods, and we fished it with sink-tips and streamers because the brook trout and salmon wouldn’t be looking up in the warm, bright weather.

I opened my streamer box and asked Rick if anything looked good among the large, drab western flies with big heads and staring dumbbell eyes. He glanced at it and scowled almost imperceptibly, then opened his own box and offered me a small Gray Ghost. Rick is a broad-shouldered, rough-hewn guy. In a diner filled with loggers and truck drivers, you’d easily pick out Carter as a fishing guide, but you might overlook Rick. He’s a policeman turned game warden turned guide and exudes the air of someone who’s seen it all (including a reported UFO crash) and hasn’t been surprised by any of it in quite some time.

We managed a few salmon, but the fishing was slowing down. There were even a few giant dobsonflies around, but although trout and salmon usually love these things, they didn’t seem interested. There was the thought that the fish were comatose in the warming water or actually absent, having already retreated to the deeper, cooler lakes to wait out the summer. That happens every year, but it’s happening earlier with global warming, making fly-fishing even less dependable than it already is. This won’t go down in the books as the worst effect of climate change, but to some of us it’s not insignificant.

That night after dinner we sat on the porch of the lodge taking turns watching the bald eagles nesting on the far shore of Aziscohos Lake through binoculars while Rick told a story about his game warden days in New Hampshire. It seems that it’s illegal in that state to keep landlocked salmon that are caught through the ice, but a fair number of fishermen were doing it anyway. So Rick trained a black Lab to sniff out these fish and played hell with the local poachers for a few years. To this day there are ice fishermen in the region who will dump their illicit salmon back down the hole at the mere sight of any black dog.

I suggested that tomorrow we take a boat out and troll streamers in the lake, which is a time-honored method in Maine. As a kid in Minnesota I considered trolling to be an antique form of punishment—like being forced to stand in the corner—made tolerable only because it might end in a walleye dinner, but later in life I’ve developed a taste for its monotony punctuated by unexpected moments of excitement. For one thing, you can do it with a fly rod. For another, you don’t really have to stop talking to avoid scaring the fish. That was just something adults made up to keep the kids quiet. There were even some big trolling streamers for sale at the lodge, including a beautiful bucktail designed by Rick called a Bosebuck Little Trout, or BLT for short. But everyone begged off, saying they didn’t have the right sinking lines. (Apparently it takes full lead-core lines to get the flies deep enough.) It was a warm, fragrant evening with the air filled with swallows, and we were all lazy from a big meal after a day of fishing. There was the strong sense of a trip winding down, as well as the inkling that I really should be at home, where I might not be of any help but where I could at least worry more effectively.

By the time I got back to Colorado the Waldo Canyon fire was under control and Ed and Jana were back home, although others in the area weren’t so lucky. Ed used to be a firefighter with the Forest Service, and in his usual laconic way he said it was “interesting” to be on the other side of things for a change.

High Park was finally declared to be contained at precisely 87,284 acres, but it’s understood that fires of this magnitude aren’t really “out” until they’re buried under snow, so there was still the possibility it could blow up again without warning. It was the thirtieth of June, with months of fire season left to go. My stuff was still piled inconveniently on the floor of my office ready to be grabbed and hustled to the car at a moment’s notice, topped by that old picture of Dad looking like the Red Baron in his leather flight jacket and goggles. I decided to leave it all there until October.