At a family reunion, my ninety-two-year-old mother asked me what was new, and I told her, among other things, that I’d bought a Jeep. She said, “You’ve always wanted a Jeep, ever since you were a little boy.” Then she added, in a less wistful tone of voice, “And anyway, you need it for your fishing.” I took that as absolution. We native midwesterners are not the frivolous kind who would fork over hard-earned money for something just because we wanted it, but as a fisherman living in the Rocky Mountains, I needed a Jeep, the way a farmer needs a tractor—never mind that he’s wanted a tractor ever since he was a little boy.

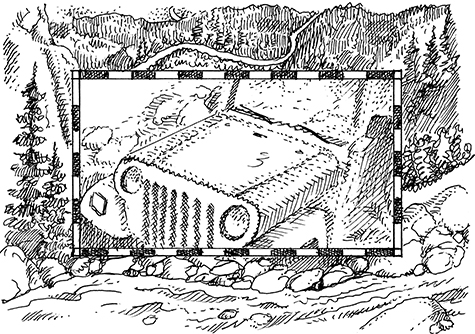

For years I made do with a succession of four-wheel-drive pickups that imperfectly split the difference between work, road trips, day-to-day errands, and the bad roads that led to good trout fishing. That accomplished the frugal goal of not having to buy, license, insure, and maintain more than one vehicle, but pickups have their limits, as I discovered years ago when I was still exploring the region I now call home. There was an obscure two-track that ran from the flats down to a creek in the next drainage that I wanted to check out. The road looked okay on the map (famous last words), and it was, except for one pitch that was steep, narrow, serpentine, washed out, boulder strewn, and canted precipitously sideways. It was the dry-land equivalent of class-five rapids, but by the time I realized I didn’t want to try it, I was too far in to back out.

It didn’t help that I was in the wrong vehicle: a full-sized three-quarter-ton pickup with a big V8 engine. This truck was the kind of indulgence some men of my generation allowed themselves back in the days of cheap gas and blissful ignorance about emissions. It had all the power and load capacity you could want, but in spots like this it was just too damned big and clumsy for its own good.

There was no alternative but to try to make it down that road. It felt like a slow-motion train wreck, although technically I was in full control of the vehicle the entire time. (Unbuckling my seat belt and propping the door open in case I had to bail out were just precautions.) At the bottom of the hill I checked the undercarriage to see if any of the hideous scrapes and bangs I’d heard on the way down had punctured my oil pan and was relieved to see that they hadn’t. I was also glad there was another road out to the state highway. It was longer by more than a mile and plenty rough in its own right, but I’d been on it before and knew it wasn’t life threatening. Later a friend informed me that only dirt bikers used that old road down from the flats. “And you did it in that big truck?” he said. “Jeez!”

I’ve gone through any number of four-wheel-drive pickups since then, most of them smaller and more agile, but they still had the common failings of a wheelbase that was too long and clearance that was too low for more advanced off-road maneuvers. And although it’s not strictly true that the best high country trout fishing is always at the end of the gnarliest road, it’s true often enough. I once drove a friend from back east to a sweet little trout stream at an elevation of around nine thousand feet. He liked the creek, with its mix of brook trout and cutthroats, but he was appalled at the washed-out old logging road that resembled a dried-up streambed. I’d told him we’d be going in on a dirt road. We hadn’t gone far when he said, “Where I come from, a dirt road is, you know, dirt. This is all, like, rocks and shit!”

For several years a friend would lend me his Jeep Wrangler for the kind of roads that had contributed to the shortened lives of some of my previous pickups. I was never sure why he was so generous, except that he’s a nice guy and a fisherman who’s often too busy to go fishing himself but doesn’t hold it against those of us who can go. I told him I’d be as careful as possible with his Jeep. He said he trusted me because I knew what I was doing when it came to off-road driving. (I didn’t remind him that I’d once earned the nickname “Hard-on” for being so hard on equipment.) Beyond that, I followed the advice of a favorite uncle about borrowing cars: “Don’t abuse the privilege,” he said, “and always return it with a full tank.”

So I was in fat city for a few seasons, but then my friend’s fortunes changed enough that he could no longer justify the expense of a second vehicle—especially one that I used more than he did. He sold it for more than I wanted to pay, but by then I was irreparably spoiled, so I went shopping for a Jeep of my own.

By “Jeep” I don’t mean the various cars and trucks that have borne that brand name over the years; I specifically mean the commercial version of the World War Two military quarter-ton 4x4 that first appeared on the market in 1945 as the CJ. (The initials stood for “Civilian Jeep.”) That first Jeep was long on practicality and short on luxury: sprung hard, geared low, and with no frills. It was envisioned as a light agricultural vehicle—an early model, the CJ-2, was called the “Agrijeep”—but the vehicles quickly caught on with the general public, and later models became progressively more carlike. The newer Wranglers are fancier and more comfortable, but they still bear a striking family resemblance to the old, no-nonsense CJs: there are still drain plugs in the floor, and they’re still small and compact, with the tight turning radius and short, eighty-inch wheelbase that lets you tiptoe over boulders that would high-center a pickup.

I thought finding a good used one would be easy, because Jeeps are ubiquitous here in northern Colorado as family cars, off-road vehicles, and fashion statements. It’s hard to make the fifty-mile round-trip to Boulder without seeing a dozen of them, from shiny new Rubicons to venerable CJ-5s and anything in between.

But Jeepology is a room with a thousand doors. Behind one is the military collector who wants a fortune for anything that’s painted olive-drab and has a crisp white star on the door, while behind the next is the guy with an elderly Jeep from the 1940s. It’s parked out back in the weeds on flat, bald tires, its brake lines have been eaten by rabbits, its hoses and belts are rotted, and mice are living in the upholstery. But he’s real proud of it because it was built by Willys Motors, the original Jeep manufacturer. “That’s pronounced ‘Willis,’ not ‘Willees,’ ” he says, as if correcting a third-grader.

Some Jeep owners have felt moved to pull the original four- or six-cylinder engines and replace them with overpowered V8s so they’ll go really fast. As an afterthought, they’ve also had to cobble together beefed-up cooling systems because the little Jeep radiators couldn’t handle the added strain. When you ask these folks why, they just look at you.

Others lean toward chrome stacks, rhino guards, light bars, painted flames, screaming-skull decals, dump truck–sized tires, and lifts so high you need a stepladder to get into the driver’s seat. “Nice,” you say politely, “but not quite what I’m looking for.”

Among the used stock Jeeps I found were plenty whose owners had been doing with them what I intended to do, and so they’d been driven nearly to death. Some no longer ran but might with extensive repairs, while many that did run qualified as walking wounded. I took one I was interested in to a garage and asked a guy named Scott to look it over. Half an hour later he walked out of the shop, wiping his hands on an oily rag, and asked, “Are you a good shade-tree mechanic?”

“No, I’m not,” I said.

“Well, then, don’t buy this Jeep.”

A salesman at a dealership was familiar with the problem. “You don’t want a used Jeep that was driven by a hard-core four-wheeler,” he said. “You want one that was owned by a sorority girl who drove it around town because she thought it was cute.”

My friend Vince helped me shop for a Jeep, partly out of the genuine goodness of his heart and partly because if I found the right one at the right price, he’d get to go fishing in it. Vince knows more about Jeeps than I do, and he’s a large man and former bodybuilder who can be usefully imposing when it comes to haggling. I’m not exactly a babe in the woods myself, but when the annoyingly slick dude at the car lot says, I think you guys are being unreasonable, Vince is the one who can deliver a line like, You’re a used-car salesman; no one cares what you think, with the authority of a Detroit hit man.

In fact, it was Vince who found the Jeep I finally bought. He called me on his cell phone and said he was standing next to a 2000 Wrangler parked on the outskirts of a nearby town. He read me the particulars off the for-sale sign, including the six-figure mileage, and said, “I think you should drive out here and look at this.”

I did, and two days later, after the usual tire kicking, test driving, and dickering, I bought it for a little more than I’d hoped to spend, but not too much more than I could afford. You know how it is: there was more to this than just simple transportation. Robert Downey Jr. once said, “Money can’t buy you happiness, but it can buy you a yacht big enough to pull up right alongside it.” Compared to even a small yacht, my new twelve-year-old Jeep was a steal. I pictured myself driving up alongside happiness and walking the rest of the way with a daypack and a fly rod.

The shakedown cruise was up a road I use as a personal benchmark, in the sense that I won’t knowingly attempt anything worse. It runs for about three and a half miles, with two fords and several white-knuckle features, including one boulder pile that’s widely known as the speed bump from hell—a short pitch of large rocks with deep washouts in between and a hard left turn just where it climbs steeply uphill. So many people have turned around here that there’s an improvised wide spot in the road. Others who should have turned around but didn’t have left the rocks scraped, skid-marked, and oil-stained.

This road finally dead-ends at a wilderness area boundary within sight of my favorite mountain creek: a sweet little thing that’s as good as it is because the god-awful trail to it weeds out the riffraff. When we got there, I leaned against a fender to put on my wading boots, enjoying the way the sound of the current harmonized with the ticking of the cooling engine. Vince and I covered a mile or so of the stream that day and caught lots of chubby, handsome little brook trout that were already in spawning colors even though it was only mid-August. I tied on the same fly I always use there—a size-16 Hare’s Ear Parachute—and left it on all day, which is sort of the whole point. If you get far enough up a bad enough road, you can find trout that don’t see a lot of flies.

The Jeep had done just fine on the way in—my tendency to ride the clutch notwithstanding—and Vince had narrated the hairier parts of the drive with stupendously filthy porn-film dialogue. I asked myself if I was being more or less careful with my own Jeep than I’d been with the borrowed one, and wondered what the answer would say about the quality of my character.

On the way out we stopped to talk to a man who was walking his young Labrador retriever. He admired the Jeep, and I told him I’d just gotten it. “What have you done to it?” he asked, and seemed disappointed to hear that I’d just had a tune-up and oil change and bought five new tires. He proceeded to tell us what he’d done to his own Jeep: a two-inch lift, titanium wheels, beefed-up suspension, a twelve-thousand-pound winch, a bank of driving lights, and so on. There are countless accessories intended to enhance a Jeep’s performance and appearance, although many of them just succeed in tarting it up, and most four-wheelers are more impressed by an unadorned Jeep covered with mud.

I didn’t bother asking the guy why he was a mile up this road on foot when he had such a spiffy Jeep. He was out with his Lab, and any dog worthy of the name would rather walk than ride.

Back out on the highway at fifty miles an hour, the pebbles that had lodged in the aggressive tread of my new oversized tires began to pop loose and hit the wheel wells with loud cracks. For the first few miles it sounded like we were taking scattered small-arms fire.

Understand that I don’t four-wheel for sport—I fish for sport and occasionally four-wheel in order to get to the places where I want to do that—but I have nothing against those who do. In fact, I don’t mind seeing them at all. For one thing, people who are out four-wheeling for fun seldom stop to fish. For another, almost to a person they’ll stop and help if you’re in trouble. Some of the more serious rigs are virtually set up as wreckers, and helpfulness is a characteristic of the enterprise. Some guys see it as a solemn duty, while others just enjoy the challenge; and if nothing else, rescuing some poor nimrod who tried to make it through in a minivan makes for a good story. There he was, they’ll say, in his Bermuda shorts and flip-flops, wondering how it all went so wrong.

Getting stuck or breaking down off-road is always a possibility, and it’s no small thing. Friendly strangers don’t always happen by, and even if they do, they can’t always help. AAA won’t come get you, and the recovery services that will can be hard to find and expensive, although chances are they’ll be ready for anything, including those drivers who thought four-wheel drive would make them ten feet tall and bulletproof. The level of assistance some of these outfits offer hints at the kind of epic trouble some people get into while four-wheeling: rollover towing, deepwater retrieval, burned vehicle removal.

The safe play is to avoid the worst calamities—even if that means parking the Jeep and walking the rest of the way—while being prepared to get yourself out of any lesser fix you might get into. With that in mind, I have a forty-eight-inch Hi-Lift jack and a tow strap (which, used together in conjunction with a chain and a handy tree, can double as a primitive and somewhat risky winch), plus a short D-handled shovel for digging out and backfilling and a bow saw for pruning the occasional deadfall. This is about the minimum equipment-wise, plus a bumper mount for the jack and bungees to secure the shovel and saw to the roll bar so they don’t bounce around and smash your fly rod.

Remember the fly rod? After all, the whole idea here was just to go fishing.