I went fishing a few days after my mother died and not long before her funeral. This was after I asked my sister if she needed me for anything, and she said no, everything was being taken care of. The subtext here is that I’m not the one in the family anyone would trust with such important arrangements. Not a dark secret; just a fact.

I thought about canceling the trip anyway out of some antique sense of a proper period of mourning, but I could almost hear Mom asking, Now what would be the point of that? She was always relentlessly practical in the way of those midwestern women who grew up during the Great Depression, and she always gave me the benefit of the doubt about my seemingly aimless little adventures. During the years when Dad all but wrote me off as a hopeless wing nut, Mom agreed but thought it was okay because I was “creative.” Or at least she hoped I was, because I was fairly useless by any other standard. They say you can’t fool your mother and they’re probably right, but they never said anything about your mother fooling herself.

So I packed my fishing gear, picked up my artist friend C.D. Clarke at Denver International Airport, and drove toward the North Park region of Colorado, up near the Wyoming border. When C.D. asked me what was new, I didn’t mention the upcoming funeral, for the same reason some people who are managing chronic conditions like diabetes keep it a secret—that is, so as not to be needlessly treated like invalids. This may be a family trait. Mom had crippling arthritis for decades, but most days when you asked how she felt she’d say, “Fine,” meaning, “Actually, I feel like hell, but I don’t want to talk about it.”

We gassed up on the outskirts of Fort Collins, then drove through Laporte and turned west up the Cache la Poudre River at Ted’s Place, once a friendly little country store and café dating to the 1940s, now a gas station and convenience store where the clerk rings up your purchases from behind bulletproof glass. It was seventy-some slow, winding miles up the canyon, most of it within sight of the river, and C. D. naturally asked about it. I said I’d always felt it wasn’t as good as it looked and that although I’d never actually been skunked there, I’d never done all that well, either. On the other hand, locals had told me that I just hadn’t put in enough time to learn the river’s peculiarities. An old story. Our dirt-road turnoff was right at Joe Wright Reservoir, with its unusual mix of grayling and rainbows, and we pulled into Rawah Ranch in midafternoon.

C.D. is a well-known “sporting artist,” a term I’d avoid if I could think of something better, because in the larger art world it’s sometimes meant condescendingly, as if an otherwise respectable painting becomes hopelessly corny the minute you put a fisherman in it. Better to say he’s a fine artist who happens to deal predominantly in sporting subjects because they interest him, and so they now form a large part of his livelihood. He’d been invited here to paint and fish by the proprietor, Pat Timmons, and was told he could bring along a friend.

No one past the age of thirteen actually believes that a sporting artist lives a life of privileged luxury, traveling the world at will, hunting and fishing at places with gillies, chefs, and wine cellars, and, almost as an afterthought, dashing off a painting every once in a while, which then immediately sells for, like, a bazillion dollars. On the other hand, judging from questions I’ve heard people at fishing lodges ask, some are curious how close a working artist can come to that adolescent ideal.

C.D. is forthcoming enough that he may have some stock answers prepared. Yes, he does regularly travel the world: Canada, Alaska, England, Scotland, Iceland, the Caribbean, the Bahamas, and so on, where he does sometimes stay at pretty ritzy places, although not always, by a long shot. (The first time we fished together, we ended up in a tent in the rain.) Yes, he studied painting formally, and yes, he does make a living by selling his work.

But that’s not what people are getting at. What they really want to know is, how do you do this? Is it hard work, or the kind of innate talent that appears effortlessly? Or do you just breathe different air than the rest of us? For that matter, do you live anything like a normal life, or do you spend your off hours sipping absinthe at sidewalk cafés with poets and philosophers? (Everyone’s default vision of The Artist is set in 1920s Paris.) A few also wonder—but don’t come right out and ask—is this just a way to get for free what the rest of us pay for? Or, as a kid in a fourth-grade class once asked me, “How much money do you make?”

How someone becomes successful in the arts when so many try and fail is a fair question, but after making an uneven living as a writer for the last forty years, I understand that no two careers are alike, and that an honest and complete answer would be longer and more mundane than anyone really wants to sit through. Eventually you learn to politely answer direct questions without addressing the preconceptions behind them—leaving people vaguely disappointed—and also that it’s best to let folks think whatever they want, including those who suspect you of running a scam.

As for that adolescent fantasy, C.D. told me that he does now and then accompany wealthy sports to places so exclusive most of us don’t even know they exist to record the trip in oils and watercolors—sort of like a seventeenth-century version of a wedding photographer. I also know that on at least some of these expeditions he arranges to put away his brushes now and then to wet a line in some of the finest fisheries on the planet.

He’s not an employee on these trips, and the clients don’t own the paintings, but they do get first dibs on them, either the small ones he does on-site or larger versions of the originals that he produces later in the studio. It’s also possible for a client to have himself painted into a composition if he’s not there already.

Roughly along those same lines, C.D. once did a slyly goofy cover painting for Fly-fishin’ Fool by James Babb. It’s a standard scene of a man fly-casting on a placid, forested river, except that the fisherman is wearing a medieval-style tricornered fool’s cap. According to a reliable source, when someone said they’d buy the painting if it weren’t for that stupid hat, C.D. painted it out.

When he’s staying at a lodge, C.D. will usually prop his finished paintings in the common room, where people can look at them at their leisure. This is a courtesy to those who are curious but too shy to snoop or come right out and ask to see the work—although if someone wants to know if a certain painting is for sale, well, there’s a good chance it is.

People do wonder about the business end (the first question the parents of an aspiring artist ask is, “But how will you make a living?”), and the artist as working stiff isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. What does come to mind might be Gauguin painting naked ladies in the South Seas; or van Gogh, the misunderstood genius who sold only one painting in his lifetime; or maybe Salvador Dalí, the playful surrealist who famously said, “The only difference between me and a madman is that I’m not mad.”

In fact, everyone comes at it differently. Some depend on galleries, while others operate their own websites and save the commissions, and a successful artist I know trusts his wife to handle all the business. “If it weren’t for her,” he said, “I’d still be hawking paintings on street corners,” which of course is another way to do it. Few artists think of their work as merchandise, but they’re all glad someone does, and there are angles to everything that you wouldn’t have thought of. I once asked a children’s author how he went about writing for little kids. He said, “I don’t write for little kids; I write for their mothers, because they’re the ones who buy the books.” As for C.D., he’s as plainspoken as his paintings: happy enough to answer questions, but just as content to let people study the paintings while he stands at a polite distance—robust, dark haired, and, as a mutual friend pointed out, bearing a striking resemblance to Clark Kent. All that’s missing are the horn-rimmed glasses.

For the next few days we fished the two miles of the Big Laramie River that the lodge owns. The river rises in the Medicine Bow Mountains in Colorado before it flows north into Wyoming, and this high in the drainage it’s a medium-sized creek running in leisurely meanders down a mountain valley. It’s a typical meadow stream, with riffles, deep pools, undercut banks, and the usual snags, brush piles, and sweepers that accumulate in water like this. There would have been a natural temptation to manicure the stream to cut down on casting and fish-playing obstacles for paying customers, but here they’ve left things as they are, maintaining it as the good trout water it is, and incidentally giving the fish the tactical advantage.

The valley is half a mile wide with slopes forested in lodgepole pine, fir, and aspen and a floor covered in dense, nearly impenetrable willows. The rustling of leaves in a breeze sounds so much like running water that you sometimes can’t tell one from the other, and the overall effect is of a continuous sigh. There are moose signs everywhere, and now and then an actual moose, looking big, dark, and imperturbable. The Shiras moose that live in Colorado are the smallest of the four subspecies in North America, but when you bump into one in a willow thicket armed only with a 5-weight fly rod, it seems plenty big enough.

The trout were the normal mix of rainbows, browns, and the occasional little brook trout: the usual suspects in water that’s been planted off and on for over half a century, sometimes with a management plan in mind, other times just with whatever was available. The biggest fish were rainbows, and I asked our guide, Jim, about them. He said the place manages for the wildest trout possible, but does do some “supplemental stocking” to keep the fish sizes and numbers where they want them, which you suspect is slightly more than the river would produce on its own. If you’re really curious about the extent to which your fishing experience has been shrink-wrapped, you can always ask, but it’s usually easy enough to figure out, since wild trout are to hatchery fish as ruffed grouse are to Kentucky Fried Chicken.

All our mornings began the same way. Breakfast was at seven, but coffee was on at six, so I’d leave the cabin at five forty-five for the ten-minute walk to the lodge, where I’d stand with an empty cup watching the last few drops dribble into the pot. I’d set an alarm but I never needed it, because C.D.’s sneaking out early would always wake me, even though he was trying hard not to. He’d found a bend in the river right behind the cabin that he wanted to paint, but the light was right only for a short time, so he had to be there before dawn. These were cold mornings, with horses in the pasture blowing clouds of steam, and I want to say he was working in fingerless gloves, but I can’t actually recall that. (Remember, this was before coffee.) C.D. would sometimes show up a little late for breakfast, and if someone said something like, “Hey, sleepyhead, glad you could join us,” he wouldn’t mention that he’d been up working for two hours.

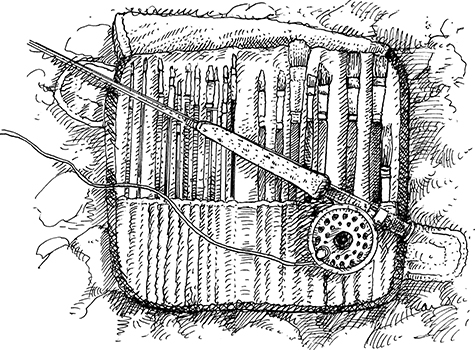

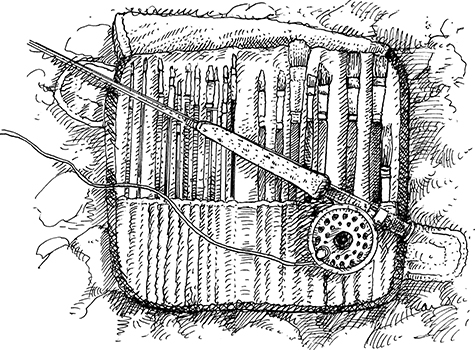

After breakfast we’d start out fishing together with Jim, either leapfrogging up the stream or taking turns on the pools. C.D. is a good fisherman and a stylish caster who never gave any indication of being distracted, but he must have been, because now and then he’d excuse himself for an hour or so to paint. He carried the slickest painting kit in a medium-sized backpack: paints and brushes for both watercolors and oils, watercolor paper and small stretched canvases, homemade drying boxes (the store-bought kind are too heavy), various other necessary odds and ends, and of course a collapsible easel and a small sunshade that looked like a miniature black umbrella. Watching him unpack and set up reminded me of that old circus gag in which more clowns than you can believe pile out of a tiny little car.

There were fish in this small water of twenty inches, plus or minus—sometimes plus a lot—and I hooked and landed some and lost others that had obviously memorized every exposed root and stump in their pools. (Big lost fish were a constant topic at dinner.) One really nice rainbow took a size-16 Quill Gordon in an eddy at the head of a run—right where Jim said he’d be—shook his head once, and ran forty yards straight downstream to a sunken root ball, where he deftly broke me off. Okay, fair enough, but then two days later at the same spot, Jim put me back on the same eddy, and when the fish made his run, Jim waded into the water and spooked him back up to the head of the pool, where we could play him out and net him. I briefly wondered if that was entirely fair, then decided that all fish caught by a guided fisherman are the result of a team effort; it’s just that this effort was more obvious than most.

After dinner at the lodge I’d hang around with the other guests long enough to avoid being rude, then walk back to the cabin and take the chill off with a little fire in the woodstove. Then I’d sit on the porch thinking things over and listening to the resident bull moose shuffling and breathing in the darkness.

My sister and I had already agreed that if we were in the same shape Mom was in at the end—in pain and with advancing dementia—we’d have been tired of it and ready to go. Of course, countless survivors have said the same thing countless times before, and you can never know for sure, but that’s what we thought. I remembered when the hardest-working man I’ve ever known dropped dead on the job and people said, “It’s the way Herb would have wanted to go,” when in fact it was the way we wanted him to go. For all we know, Herb might have preferred a beach in Mazatlán.

I reminded my sister of the time Mom wanted to talk to me about her “estate,” which wasn’t all that much even then.

I said, “Nothing would make me happier than to learn you’d spent your last dollar on the day you died.”

She said, “That’s funny—that’s exactly what your sister said,” and it seemed to please her. Of course, in my ignorance I pictured the money going for cruises and wine-soaked lunches with friends instead of the doctors and nursing homes where most of it eventually went.

After a certain point everyone’s life is informed by loss. It’s not surprising, but it’s still a surprise. The permanence of it feels like a life sentence, and there’s always an echo of selfish regret: if there was anything that could have been made right, it’s too late now, and it always will be. And the oddly practical question of “What now?” arises. For one thing, Mom now joined the growing number of dead people in my address book whose names I don’t have the heart to cross out and who may eventually come to outnumber the living. For another, there are still those two categories of things that your mother must never know and small victories and accomplishments that she’d enjoy hearing about, except they’re now both moot.

And there’s the odd way memories sink in one place as the initial sting wears off and then resurface unexpectedly somewhere else. I think of some of the people I’ve lost every day, while others hardly ever come to mind, and it has nothing to do with how often I saw them, how much I liked them, or how many years have passed. The same goes for the animals I’ve lived with. Some of my old dogs and cats seem to have closed the books and moved on, but I can’t shake the feeling that my favorite tomcat is still hanging around the place, hunting ghost rodents and napping invisibly in the sun.

C.D.’s paintings predictably appeared on the mantel in the dining room: first the watercolors that were each done in a single sitting, and then later the oils that took days to complete—one of the bend in the river behind the cabin at first light, the other of the fishy pool under a decrepit wooden bridge farther downstream, where I never did manage to hook a trout. The sunrise felt serene while mercifully falling short of being inspirational, and the bridge—my favorite of the two—had an understated brooding quality, but don’t ask me how either effect was achieved. Presumably fishermen could later be added to any of these, but as they stood they were entirely realized unpeopled landscapes that I won’t try to further describe in print except to say that the same friend who pointed out C.D.’s resemblance to Clark Kent called him “a sporting man’s Monet.”

The few times I’ve asked, C.D. has explained to me in detail what he’s doing in terms of the relative values of colors, how diminishing detail is used to suggest receding space, or how the intricacies of composition keep your eye within the frame. I understood the techniques, but not how they rose above being exercises in craft to become works of art. We’ve also talked about our respective work habits, which in his case seem to be composed of roughly equal parts compulsion, self-indulgence, and good old American work ethic. But on a couple of trips where we’ve traveled, fished, and roomed together, I’ve never heard him say anything the least bit lofty or philosophical about art. Like other artists I’ve talked to—not to mention actors, musicians, writers, and many fishermen—C.D. seems to have long since left considerations of why behind and is now entirely engrossed in how. He simply does the work, puts it away, and then goes fishing.

But the one thing C.D. is adamant about is the efficacy of plein air painting: working outside, on-site, with natural light shining on actual objects. He doesn’t see how you could get it right any other way, and when he puts it like that he’s entirely convincing, but of course others do it differently. One of my favorite paintings, by my friend Bob White, was done in his studio several years ago based on a series of photos I sent him of a place he’s never been. The scene is of C.D. himself painting in the rain on a remote river in Labrador under the shelter of a plastic tarp, which Bob wisely changed from its original toxic-waste green to brown.

Sentiment keeps me from being an objective critic here. I’m too enamored with the idea of one artist I like working in a studio in Minnesota depicting another artist I like working out in the weather in northeast Canada with little old me and my waterproof digital camera as the go-between. Still, I’ll go out on a limb and say process is crucial to the individual artist, as it should be, but in the grand scheme it doesn’t matter how you did it as long as you got it right.

The funeral back in Missouri went as expected. There was the short, vaguely religious service; the church basement lunch of midwestern comfort food, with all of us looking slightly uncomfortable in clothes we otherwise never wear; the often repeated family stories that change a little with each retelling; and the predictable examples of small-town wisdom, as when a cousin said, “Burying your mother is no fun, but at least it’s a chore you only have to do once.”

And then someone put a hand on my shoulder and asked, “So, where are you going fishing next?”