In mid-August we flew to the headwaters of the George River at Lake Juliette, just over the Labrador border into eastern Quebec, and launched a pair of twenty-foot fiberglass canoes. As far as we knew, we’d be only the fourth party ever to canoe this part of the river. The first two were the Mina Hubbard and Dillon Wallace expeditions way back in 1905. Both groups crossed Labrador using slightly different routes, portaged over a low rise of land into the headwaters of the George in Quebec, and then floated some 350 miles north to a trading post on Ungava Bay. That was two years after Mina’s husband, Leonidas, died of starvation and exposure before reaching the George on his party’s failed 1903 attempt. Then, in 2003, another group mounted a successful fifty-day, 650-mile canoe trip to commemorate the Leonidas Hubbard expedition that had gone so wrong a hundred years earlier.

As far as we knew, that was it. People do occasionally canoe the George, but they paddle down the de Pas River from Schefferville to Indian House Lake (or Lac de la Hutte Sauvage) and then follow the bigger water on to Ungava Bay, bypassing over a hundred miles of the headwaters we had our eye on.

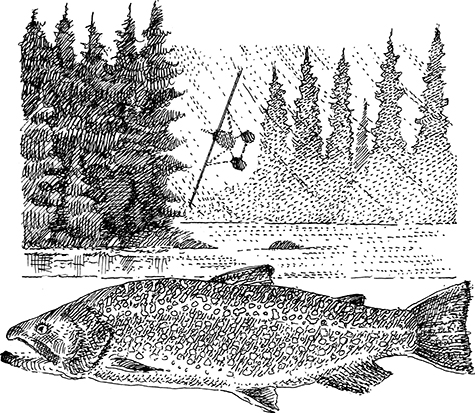

But we weren’t out to do that kind of heroic paddling; we were just interested in the fishing. We assumed there’d be brook trout in the upper George because they were known to be in the lower river, although we didn’t know how big they’d be, and we thought that by August some landlocked salmon might have migrated that far upriver. Either way, it was doubtful any fish in that stretch had seen an artificial fly in its lifetime.

There were six of us. Carter Davidson, the filmmaker from Maine, was there to shoot a documentary on landlocked salmon.

Aimee Eaton is a fishing and nature writer from Colorado who said she didn’t even know where Labrador was when she got Carter’s call.

Simon Guay is a French-Canadian fishing guide who knows as much as anyone about brook trout and salmon, but freely admits that northern pike are his favorite fish.

John Reitman is an ex-military man who’s so vague about his time in the service that you suspect he was ordered not to talk about it. He said his personal motto is “semper Gumby” (always flexible), and he’d brought along two things you should have on this kind of trip but hope you won’t need: a first-aid kit extensive enough to do minor surgery, and a big-bore rifle.

Robin Reeve owns Three Rivers Lodge in Labrador—our jumping-off spot for Lake Juliette. I’ve known him longest and best, and one thing I know is that he has a penchant for scouting trips that are supposedly aimed at opening new water for the lodge but that invariably turn out to be too complicated and expensive to dollar up with clients. I think he just wants an excuse to fish new rivers, but I’ve never asked him about it for fear he won’t invite me on any more of these fool’s errands.

And then there was me, in my capacity as editor-at-large for Fly Rod & Reel magazine: a more or less honorary title I secretly like, because I think the phrase “at large” makes me sound dangerous.

For a while it looked like this trip wouldn’t happen. By the time we got to the lodge, southwestern Labrador was socked in with cold wind, continuous rain, and a ceiling that seemed to lower by the hour without ever quite reaching the ground. Good weather for poking a fire in the woodstove and sipping coffee; not so good for wilderness canoeing and camping, let alone getting to the river by floatplane in the first place.

We chanced a shorter flight to Indian Rapids, a wide, riffly channel between two lakes that Robin said might or might not hold brook trout or landlocked salmon. This late in the season both species are migrating upstream to spawn, and their whereabouts in these vast, complicated drainages aren’t easy to predict. We landed a five-pound and a six-pound brook trout and lost a third, but there were no salmon.

Day two was dark, raining hard, and chilly enough to see your breath, but not quite cold enough to put off the intrepid Labrador mosquitoes and blackflies. We flew one drainage west to the McKenzie River, where a lodge owner Robin knew had no fishermen in that week and said he’d help us look for salmon.

We hiked two miles downriver in a steady rain on a trail that was several inches deep in standing water and used the boat that was stashed down there to ferry across a small lake. At the outlet Aimee hooked a salmon that jumped once and came off, and in the river downstream Robin hooked and landed a fat salmon of about eight pounds. Those fish cheered Carter up considerably, but they were the only ones we found.

On the way back we saw a large bear turd next to the trail that hadn’t been there on the hike down a few hours earlier. The bear had obviously been feasting on blueberries, because this turd was not only bigger than average, it was the most surprising shade of purple. Carter stopped to take several close-up photos of it. No one asked why.

Back at the camp, wind and rain were howling across the lake, visibility was down to a quarter mile, and our pilot, Gilles Morin, said we’d be unable to fly back. We sat in the kitchen at the empty lodge drinking coffee strong enough to warp a spoon while the owner said he could feed us “something out of cans” for supper and that we were welcome to his vacant bunks. We were just settling in to the idea of staying the night when Gilles came in from checking the plane for the third time. He didn’t like the way the waves were slamming the pontoons against the dock, but there was no sheltered place to tie up, so he thought we should “try to make it back” before dark.

We took off into cloud cover low enough to obscure the treetops, but by staying under the low overcast we could see well enough to bank around the hills and feel our way back to Three Rivers, wiping the condensation off the inside of the windshield with a canvas work glove. We were flying in a small plane in weather that would make me think twice about driving my Jeep, but I’d flown with Gilles on previous trips and shared Robin’s confidence in him. He’s a small, precise man in a leather jacket and baggy hip boots; not at all shy, but not overly talkative, either, with an uncanny sense of weather and a reputation as a pilot who can perform borderline miraculous feats with a de Havilland Beaver.

The whole George River plan depended on Gilles. The common wisdom was that once you pushed off from Lake Juliette, you’d have to go something like fifty or sixty miles before coming to a place where any sane pilot could land to pick you up. Above that, the river itself was too narrow and serpentine, and although there were some pond-like wide spots that looked promising on the map, Gilles had scouted them from the air and said they were too shallow and rocky. But he had located a stretch of river that was wide enough, deep enough, and just long enough to land a floatplane—and, more important, take off again with a payload.

Had he actually done this, or had he just scoped it out from the air? At times a slight language barrier kicks in with Gilles. He speaks some English, but his first language is French, and the only French I have is what I’ve picked up from the multilingual signage in Montreal and Quebec City. I can say “exit” and “napkin” and “thank you,” which is not the stuff of nuanced conversation. For his part, Gilles sometimes falls back on one of those eloquent shrugs the French have perfected—a shrug that in this case seemed to say, “Having actually done it and just knowing I can do it amount to the same thing.”

We had a meeting the morning of day three. We didn’t have unlimited time to wait for conditions to change, but there was the question of whether we could fly to the George in this weather, and even if we could, none of us was anxious to rush into a survival situation. Someone pointed out that there are two ways to get hypothermia on a canoe trip in the rain: gradually or suddenly.

We made a quick hop out to Rick’s—not to be confused with Middle Rick’s, Upper Rick’s, or Rick’s Surprise. This was a small, steep, alder-choked channel between lakes that reminded me of a creek in the Rocky Mountains, except that the brook trout there weighed between one and a half and two pounds. These aren’t impressive fish for Labrador, but Aimee said she couldn’t bring herself to think of a two-pound brook trout as “small.” Neither could I.

At the inlet to the next lake I hooked something heavy on a weighted streamer, and Carter filmed while the fish ran me out into the backing and spit the hook. Carter said it must have been a lake trout or a pike, because a salmon would have jumped.

On the morning of day four the weather broke chilly and bright with high, soggy-looking clouds in a blue sky, so we hustled our gear together and flew to Lake Juliette. It took three long trips: one with the canoes—which have to be strapped to the pontoon struts, where they cause aerodynamic problems—another with gear and provisions, and a third with the fishermen. Then there was the painstaking business of distributing and balancing the loads in the canoes and the required group photo that Carter insisted on taking so he wouldn’t have to be in it. (For a filmmaker, he’s oddly camera shy.)

The George began unspectacularly, spilling out of the lake into a wide, bumpy riffle that was so unreadable we simply entered it at random, steering around visible rocks, watching for deadheads, and getting a sense of how these boats handled, which wasn’t well. Even empty the big canoes weren’t exactly nimble, and loaded down with gear and fishermen they felt waterlogged and unresponsive.

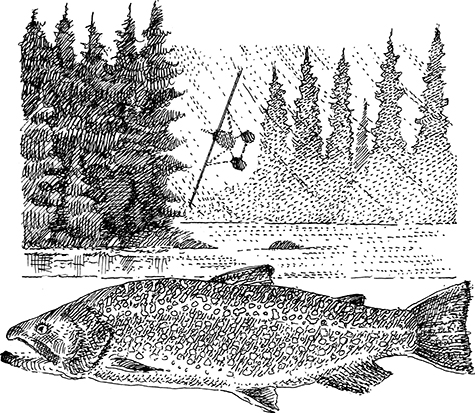

The river flowed placidly through flat country left behind by the last ice age, but now and then there’d be enough of a drop to create rapids that we’d either run or walk the canoes down. At the bottom of these there’d be a fan of current spreading into deeper water, and that’s where we got into brook trout: big ones of four to six pounds at the lip of the rapids, and smaller ones of a pound or so above that in the pockets. Not a lot—a few at each spot at best—but fat, wild, beautiful, innocent fish.

Simon, Robin, and I were paddling downriver toward one of these spots—rubbernecking at the fishy water below—when we abruptly got sideways in the rapids. I’m not sure how it happened. At first it looked like we’d taken a good line, and then it didn’t. All I clearly remember is John’s worried, helpless look from the other canoe as he tried to work out how to help and couldn’t come up with anything. In the end, we managed to keep the canoe from capsizing, but we lost a paddle. No harm done, since we had a spare, and anyway things had gotten a little dreamy by then, and it was a useful reminder that a river will purr like a kitten if you pet it right, but it’s still an unpredictable animal that’s capable of anything.

We camped in wet woods with a floor of lichens and caribou moss that had the consistency of a damp sponge and looked like it should be growing in a petri dish. We pitched the tents far away from where we cooked and roped the provision boxes up in trees in case the food smells attracted a bear. They say this region is lousy with bears—hence John’s rifle—but then, no one ever comes here, so how would they know? In fact, this was inhospitable country without much to eat, and so wildlife was scarce. In our entire time on the river I saw exactly two ravens, one boreal chickadee, and one golden eagle. That’s it. We never saw a mammal of any kind—not the bear, moose, or caribou you’d expect in northern wilderness; not even a squirrel.

I had an old pocket watch in my gear, but didn’t see any point in winding it, so it eventually stopped. (I don’t mean that metaphorically; there was just no reason to worry about what time it was. The same thing sometimes happens at home.) Meanwhile the landscape unrolled, with its stunted black spruce, spindly tamarack, and muskeg where our footprints sprang back almost as soon as we made them. It was so quiet away from the rapids that even a pretty little riffle around the next bend sounded like Victoria Falls. This landscape was exactly how it’s always been and how it’s supposed to be: a place where you can experience the peculiarly modern pleasure of being pretty sure you’re not under surveillance.

The fishing was good, but no better than in places that were much easier and cheaper to get to; the trees were too small for lumber, the scenery was unspectacular, and no minerals worth extracting had been found. This wasn’t designated wilderness but wilderness by default: a remote northern region where no one had yet figured out how to make a buck.

I remembered that E. Donnall Thomas Jr. once wrote, “It is shocking to realize that our greatest accomplishment as a species may be to escape all traces of ourselves.” That made me think of poor Leonidas Hubbard, who was so eager to make his mark in the waning days of the era of exploration. He believed the region would be teeming with enough game to feed his party and realized only by degrees that he was wrong. If he’d made it this far, there might have been the ancestors of these fat brook trout to eat, but as it was, he escaped all traces of his species, and his last meal consisted of his moccasins, or so the story goes.

The woods were so wet that we ended up living in our waders except while we were sleeping—pulling them on in lieu of pants every morning—and even then by day two everything was clammy. Even the spruce twigs we broke off for kindling were rubbery with moisture and draped in the greenish-gray lichen known as witch’s hair, so our fires tended toward the smoky side.

With six of us in camp, the chores went quickly. The last thing each night was to boil a big pot of water that we’d use to fill our canteens the next morning—except for Robin, who drank straight from the river out of habit. It was probably safe, but the rest of us had all had giardia at least once and didn’t want to get it again, especially out here. Whatever wilderness epiphany I might have hoped for arrived in just those kinds of practical terms: this was no place to dump a canoe, twist an ankle, or get the Hershey squirts.

Carter filmed it all diligently but unobtrusively, without making us feel we were on a movie set, although I suppose technically we were. He never seemed disappointed that none of these fish were the landlocked salmon he and his sponsors were hoping for, although he sometimes wore the thoughtful expression of a man who was rethinking a project on the run. Every documentarian knows there can be more than one true story in any sequence of events, and this was beginning to look like a story about brook trout.

And why not? These north-country fish are just handsomer than other brook trout—especially in August when they’re fat from a short growing season and colored up for the spawn—and they’re uniformly bigger than they get anywhere else. It’s a function of inhabiting the northernmost end of their native range, where they live long, hard lives in conditions that would kill lesser fish. They can be hard to find, and once you find them you usually won’t catch very many, which only makes the ones you do catch more vivid. I’ve been coming to this region on and off for twenty years now for the simple reason that I don’t know what I’d do without these beautiful brook trout.

One day I was perched on a rock at the bottom of wide, stair-step rapids fishing a streamer on a sink-tip line. I was casting parallel to the rapids, stripping back through the broken water, and then working out in a fan pattern into deeper current braided by sunken boulders. It all looked fishy as hell, and I couldn’t imagine any brook trout in here being able to resist my size-4 Red Ghost, so I wanted to make sure they all had a chance to see it. When I got a take I set hard and saw a thick flash of orange as the fish rolled. I played it carefully—maybe even timidly. I’d lost a good one earlier by getting impatient and trying to rush it to the net, and none of us were catching so many that we could easily shrug off a blown chance.

These fish aren’t flashy fighters—there are no jumps or long, reel-screaming runs—but they’re muscular and dogged and put up an awful commotion when they’re hooked. It’s hard to describe the physics and tactics of landing a fish beyond John Casey’s admonition that “when the fish does something, you do nothing, and when the fish does nothing, you do something,” but it’s fair to say that if you play it too hard, you’ll lose it, and you’ll also lose it if you don’t play it hard enough. There are those who say they fish to relax, but how can you relax when there’s so much at stake?

Finally Simon dipped up the perfect brook trout in his long-handled net. It was a six-pound male built like a cinder block with a humped back, wide shoulders, and hard gut, wearing his best orange spawning colors. This was a prosperous fish in his prime, and if he had a thought in his head, it was only to pass on his blue-ribbon genes. After I released him, Simon shook my hand as if I’d just won a Pulitzer Prize, which is more or less how I felt.

We got in a little fishing on our last morning, but had to get back early to break camp before the plane arrived. Carter, Aimee, Robin, and I went out first, along with some of the gear, while John and Simon stayed to finish packing. Once we’d loaded up, Gilles taxied so far upstream that when he swung the plane around, the rudders of the pontoons barely cleared the rocks at the bottom of the next riffle. As soon as we were facing downstream he pushed the throttle all the way forward and the plane roared and lurched. I didn’t see how this could work. A floatplane needs a certain minimum amount of room to get airborne (more than it takes to land; even more with a load on board), and the black spruce woods at the next bend were too tall and entirely too close. I wished I’d cleared up the question of whether Gilles had actually done this before or just thought he could do it. I wondered whether John and Simon had sent us out first just to see if we’d make it.

By the time the pontoons came off the water the trees had filled the windshield, and we weren’t gaining altitude fast enough to clear the crowns. Given time to think it over I might have concluded that this was a better place than most to check out, but in the moment I just thought it was all happening too fast. I’d just braced for impact when Gilles banked hard to the right, flying sideways below the treetops around the sharp bend in the river with one wing nearly cutting a wake in the water until he had room to level off and climb out. It was all in a day’s work for a bush pilot Carter would later describe as “ninety-nine percent business and one percent crazy,” and even before I managed to swallow the lump in my throat, I was happier than I’d ever been to be alive and in the air.