Someone had spray-painted “Rehab is for quitters” on an otherwise blank concrete wall. This was in the Designated Smoking Area outside the Anchorage Airport where I was waiting out the third consecutive delay of my flight with some strong, silent types I took to be commercial fishermen. (Roughnecks from the oilfields have a more sullen look, and everyone else dresses better.) Flight delays are so common in Alaska that waiting gracefully becomes a necessary skill, and since it’s done in public, there’s an element of performance to it. I try to imagine myself as a character actor—maybe a Bruce Dern type—playing the role of the veteran north-country traveler who understands that no amount of fretting and whining will make the plane go if the plane isn’t going. Meanwhile, the real old hands simply find a patch of unoccupied floor and lie down for a nap, hugging their backpacks as though they were feather pillows.

The flight was finally called three hours late, and my friend Ed and I walked out onto the tarmac with a dozen other sports and climbed aboard the little turboprop Saab 340. We fastened our seat belts, they started the engines, and we waited for the plane to move. A few minutes later the engines sputtered to a stop and the pilot came out and asked if we’d please go back inside and wait in the terminal. He did say “please,” but it wasn’t a request.

From inside, several of us watched as a guy pulled up in a van, climbed a stepladder, and began tinkering with the starboard engine. (Work of this kind is deeply fascinating when it’s being done on a plane you’re about to fly in.) Sometime later he replaced the cowling, the pilot restarted the engine, and they both stood a little distance away talking. I couldn’t help but imagine the conversation:

There. How’s that sound?

Sounds like a weed whacker; you expect me to fly that thing?

We got back on board, and this time the plane taxied smartly out to the runway. I don’t have more than the usual fear of flying, but I did hope the aircraft would work this time and that to a trained ear both engines would sound more like Maseratis than weed whackers.

Soon we were at altitude and flying southwest toward Bristol Bay. Off the left side of the plane a river poured through a canyon into the Gulf of Alaska. Off to the right its corrugated headwaters reached to the horizon with blue-green glaciers nestled in their cirques. Only minutes by air from the biggest city in the state, and already the landscape seemed unimaginably somber and remote. When the guy in the seat ahead of me came back from the bathroom, he said to his seatmate, “That toilet is so small I ended up pissing in my hat by mistake.”

At the lodge we suited up and motored down Aleknagik Lake to the mouth of the Agulowak River with these ancient Athabaskan names catching in our throats like chicken bones. At this time of year—mid-July—three- to four-inch-long sockeye salmon smolts pour out of the river by the tens of thousands on their way to salt water, and Arctic char and Dolly Vardens stack up there to ambush them. It’s a perfect setup for fish and fishermen.

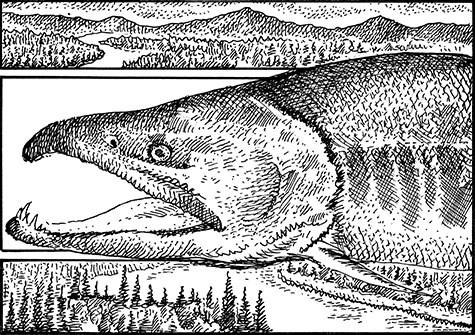

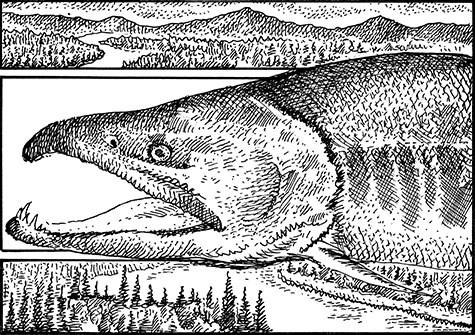

When we came around the last point we could see it was in full swing. There were half a dozen other boats anchored or drifting near the mouth—two that we recognized from the lodge, the rest probably up from Dillingham—and the air was filled with wheeling and diving Arctic terns, while fat white gulls bobbed around like anchored yachts. Fish were milling all over, but every few minutes a pod of char would push a school of smolts to the surface and a quarter acre of fish would boil past the anchored boat at current speed. When one of these frenzies went into a window in the glare you could see it all clearly: hundreds of silver smolts flashing like welding sparks in the sun, and uncountable ominous shapes looming up from below like something from a painting by Hieronymus Bosch.

The Agulowak is a big river, so multiply that by a current plume hundreds of yards wide and a quarter mile long, where seven boats are spaced far enough apart to avoid tangling lines even on long runs, and in each boat there’s at least one fisherman holding a bent rod. This is the kind of jaw-dropping abundance that draws fishermen to Alaska and that also sometimes produces cases of shameful fish hoggery. I don’t mean the locals who diligently fill freezers with fillets because winters here are as certain as death and taxes; I’m talking about dentists from Omaha who lug home coffin-sized coolers of fish that their wives won’t know what to do with. A few big meals where Dad brays about being the hunter-gatherer back from the wilderness, and the rest is lost to freezer burn.

I once overheard an argument between one of these privileged dimwits and a bush pilot who’d spent one too many seasons watching the pointless carnage.

“Why shouldn’t I bring home fifty pounds of salmon? They’re gonna die anyway.”

“They’re gonna die after they spawn, and every one you kill is one more that doesn’t. Are you really too stupid to see that, or are you just playing dumb so you can go on being an asshole?”

The next day we flew out to a compact little tent camp on the Togiak River: a couple of WeatherPorts pitched on an open coastal floodplain with a fire pit and improvised driftwood lawn furniture out front. There we were told that the king salmon fishing had been “slow”: a fisherman’s euphemism for “pointless.” For weeks now the weather had been sunny and warm for Alaska, and a lack of rain had kept the Togiak and other rivers in the region low and on the warm side. Some said the kings had petered through early—a few at a time, but never in fishable numbers—and were now far upriver spawning. Others thought the few that had been seen were advance scouts and that the bulk of the run was still staged in salt water, waiting for gray skies and a flush of water. Less analytical types just thought it was a rotten year for kings.

Our guide, Taylor, said chums were a better bet. Most were already in and spawning, but there were still plenty of stragglers we could fish to. And of course the Dollys were almost a sure thing. They’d be staged just downstream of the spawning chums picking up stray eggs, and would be pushovers for orange plastic beads. Ed and I exchanged a look and said we’d like to try for kings.

The run Taylor took us to had a sloping pea-gravel bottom dropping into a slot where the current ran smooth, deep, and deceptively fast against a far bank lined with black cottonwoods. This is where the kings would be. Taylor had seen them there as recently as the day before, but said they “weren’t doing anything.” I looped the heaviest sink-tip I had onto my Skagit head, dug out a five-inch-long Intruder fly I’d slaved over the previous winter, and asked Taylor what he thought of it. He said, “Yeah, that could work,” with the guide’s typical emphasis on “could.”

Ed and I fished through the run, casting tight to the far bank and then throwing big, loopy mends to sink the flies as deep as possible before they started to swing. I wasn’t sure I was getting deep enough, but I couldn’t think of how else to do it. When Taylor waded in and stood off my left shoulder, I said, “I’m open to suggestions here.”

He said, “Yer fishin’ it like I would.”

He was handling us. We were here only for the day and we wanted to do the one thing that wasn’t going to work, so rather than trying to talk us out of it, he was letting us knock on this door until it was obvious even to us that no one was home.

When we felt we’d given it our best, we piled into the johnboat and drifted over the run to have a look. The salmon were podded up right on the bottom in the gut of the run, six or seven of them, startlingly big and motionless as logs. Fish like these are said to be “sulking,” as if they’re not just uninterested in your fly but are punishing you for some perceived insult and refuse to bite out of sheer peevishness.

Without saying “I told you so,” Taylor then took us to two other pools where chums were rolling in the hard current, and we caught some. These fish usually come in third in the Pacific salmon sweepstakes, after kings for their size and silvers for their numbers and aggressiveness. Chums aren’t classically pretty salmon by a long shot, but they wear their snaggle-toothed homeliness with style, bite a fly angrily, and fight like wolverines. So what’s not to love?

Late that afternoon we flew to Birch Creek Camp. As we humped our gear up from the plane, I asked one of the guides, Jason, why it was called that, since it was actually on the Middle Fork of the Goodnews River. He said the name dates to the early days of the lodge, when the original owners were scouting locations. They didn’t want anyone who might be eavesdropping on their radio chatter to know where they were fishing, so they made up fictitious names for the rivers. I pushed my luck and asked, “What was the news that was so good it has a river named after it?” He didn’t know.

Ed went off with Eric, the other guide, to catch some Dollys before dinner, while I sat in a folding chair in front of my tent to untangle my backing. On the last pool on the Togiak I’d foul-hooked a large chum right ahead of the dorsal fin, giving it extra leverage and making Taylor and me think it was a big king. We chased it in the boat, and in the ensuing confusion I managed to repeatedly wind my line and backing onto the reel in sloppy overlapping loops that then cinched themselves into a seemingly endless series of world-class granny knots each time I came tight to the fish. I could have put away the spey rod and fished a one-hander for Dollys at Birch Creek, but I’ve become a stickler for keeping my tackle in order, because some of the slapstick routines from the days when I didn’t are still vividly painful memories.

By the time Ed and Eric got back I’d finished my chore and was relaxing, watching the wakes of chum salmon running up the riffle in front of camp and wondering if untangling backing for eternity would be my job in hell. When Ed walked up from the boat, I asked, “How’d it go?”

“We just now came around a bend tight to the bank and almost bumped into a sow brown bear with a cub,” he said. “They were really close.”

“How close?” I asked.

He said, “If they’d jumped one way instead of the other, they’d have ended up in the boat.”

Ed was still wide-eyed with adrenaline, and I knew the feeling. All tourists love to see bears at the kind of respectful distance that mimics a TV screen, but it’s the sudden, close-range encounters that reveal these animals for what they are: not so much romantic icons of wilderness as six-hundred-pound meat grinders.

As an afterthought, Ed added, “We caught a shitload of fish.”

We spent the next day catching Dollys and rainbows on beads and flesh flies. On my first trip to Alaska I had to get used to the idea of these noble game fish gorging on stray salmon eggs and shreds of rotting flesh as a succession of five species of Pacific salmon run up the rivers to spawn, die, and decompose—not to mention fishing flies tied with sickly pinkish-beige rabbit fur intended to imitate rancid meat. It’s one thing to be told that the entire ecosystem here depends on countless tons of dead salmon and that without those nutrients brought inland from the ocean every year, Alaska would be a cold, fishless desert, but once you actually see it you realize that this is the aquatic version of fifty million buffalo.

The most striking example I ever saw was one September on the Karluk River on Kodiak Island. Miles of riverbank to the high-water line were ankle-deep and slippery with the corpses of pink, sockeye, and silver salmon, and the river itself looked and smelled like a cauldron of spoiled cioppino. Kodiak bears the size of pickup trucks were greasy with fish oil and so stuffed with salmon they could hardly move. Likewise, the big, sleek Dolly Vardens in from Uyak Bay were so full of salmon eggs they were dribbling them out their gill covers. If you’ve ever fished with dead drift nymphs, beads will be a familiar form of manipulation, but these fish would chase a bead even on a swing, apparently so blinded by gluttony that it didn’t occur to them that eggs don’t swim. This is the best reason to go to Alaska: not for the chance at fifty-fish days but to see for yourself that nature isn’t the least bit dainty or sentimental.

We had a good day on the Agulupak River, where we caught rainbows and big, pretty graylings on dry flies with my old friend Bob White and had one of his famous shore lunches of fresh sockeye salmon, fried potatoes, and the breaded and fried green apple slices known as “guide pie.” Ed and I ate as if we hadn’t seen food in a week, while Bob nibbled on a single piece of fish. “If I ate like that every day,” he said, nodding at my second tin plate of fried fish and potatoes, “I’d weigh three hundred pounds.”

Bob is a successful artist with a serious guiding habit who can’t seem to stay away from Alaska. He’s been guiding for a long time and looks it, with windburned cheeks and a beard like steel wool. I don’t know if he has actual seniority at the lodge (the pecking order isn’t obvious to outsiders), but the other guides look up to him as an elder statesman and role model. When one young guy made a shore lunch that was almost an exact copy of Bob’s and I asked him about it, he said, “You quickly figure out that however Bob does it is the way it should be done.”

The fishing was dead at Rainbow Camp—another example of forty-year-old misdirection—where we arrived on the downside of the boom-and-bust cycle. The kings weren’t there for reasons that were open to discussion, and the chums were spawning farther up the small river than we could get by boat, with the Dollys and most of the rainbows right behind them.

We motored upriver anyway to see what we could find, slowing in one pool to miss the single handlebar of a snowmobile that was protruding just above the surface. It hadn’t been there when I’d fished the river the year before, and Matt and Tyler said they didn’t know the story behind it, although it’s hard to imagine a scenario set in an Alaskan winter that starts with a snowmobiler going through the ice miles from the nearest settlement and ends happily. They said they’d kept an eye out for a body for the first few weeks in camp and then pretty much forgot about it.

We swung a few deep pools to see if maybe an errant king salmon was around, but mostly because we needed something to do, since we all understood that nothing much would happen here until the silver salmon arrived in a few weeks. It would have been a good day for a boat ride, some bird-watching, and a leisurely lunch, but guides hate to send their clients away skunked, so Matt found a pair of spawned-out chums and put Ed into a couple of rainbows staged below them that ate a flesh fly. And later I got a rainbow on a mouse pattern by following Tyler’s detailed instructions. He called the strike so accurately that I had to suspect this was the camp pet, usually reserved for children and beginners. Nice fish, though.

It was hot enough on the flight back to the lodge that we flew with the windows of the Beaver open, enhancing the illusion that these things are just flying pickup trucks. While we were still climbing I saw two bald eagles sitting on a rock at the top of a hill looking up at us with obvious disdain. Later there was a pair of white trumpeter swans posing on an emerald pond like ornamental swans on an English estate, and farther on there were a bull moose with giant antlers and several tributary creeks running red with sockeye salmon.

There’s a lot to be said for these lodges that operate on the grand-tour model. For one thing, you see six or seven rivers at close range and lots more beautifully empty country in between from a floatplane, which incidentally fulfills a childhood fantasy of mine sparked by overwrought stories in Field & Stream. Also, when the fishing sucks—as it occasionally does—you know you’ll be somewhere else tomorrow where it will probably be better. The flip side is that when the fishing is fabulous, you know you’ll be leaving on the same plane that brings in your replacements, so it’s possible to begin getting nostalgic by lunchtime. And as the trip winds down there can be the sneaking suspicion that although you saw multiple rivers and caught countless fish, you never quite sank your teeth into anything.

This can make you mildly jealous of the guides who work there and live what seem like enviably authentic lives at the camps you only visit for a day. Still, you avoid gazing around admiringly and saying, “God, what a place to spend the summer!” because the guy’s heard it a hundred times and might reply, Yeah, well, you can’t eat the scenery. There’s sometimes a fundamental disconnect between guides in their twenties and thirties and clients at the deep end of middle age. This can be as complicated as fathers and sons or as simple as the fact that, as Gina Ochsner put it, “Young men drink because they don’t know who they are, and old men drink because they do.”

On our last day we ended up back at the mouth of the Agulowak, fishing for the same char and Dollys that were plenty big and fat a week before but that were now fatter and a couple of inches longer on average. That was hard to believe, until I considered the staggering amount of protein that changes hands in these transactions: enough that you could actually see the fish had grown in a week’s time.

We were casting across and down current, fishing a slow swing with any streamer fly that was large and predominantly white. Intuition said to strip fast to mimic the panicked prey, but we’d learned all that would get you was foul-hooked fish; there were that many char in the water. I said I thought the fish were taking our slowly drifting streamers for stunned or injured smolts and got noncommittal shrugs from Ed and our guide, who both understood that when fish are gorging like this it doesn’t matter what your fly is doing as long as it’s in the water.

We were back at the lodge early, taking hot showers and packing up for the flight out in the morning. Anglers travel a long way to find a seemingly inexhaustible supply of big, wild, gullible fish, but unless you’re trying to feed a village for the winter, there’s no reason to catch a boatload. After five fish in a row you can say you’ve figured it out; at ten you’ve made your point; and somewhere short of twenty a sense of unease develops that could easily blossom into embarrassment. The trick is to enjoy the spectacle and then quit while it’s still fun.