When the power went off during an April snowstorm, I plugged the chest freezer into the generator so the food wouldn’t spoil. This was the new generator, a 3,600-watt Yamaha that mutters politely in the background, unlike the old Briggs & Stratton I used to have that made such a racket I was tempted to trade my frozen steaks for some peace and quiet. We’re on a rural electric co-op here, and the power goes off three or four times a year on average—not always for obvious reasons like weather—so a generator is standard equipment.

We got only two or three inches of snow in the valley before it turned to sleet and then rain, but just to the north, through the rest of Larimer County and on into southern Wyoming, as much as fifty inches of wet snow fell in three days, clinging to power lines like kudzu, and that was all she wrote. You forget that your house is an electric appliance until it abruptly goes dark.

By then we’d been fishing the spring Blue-Winged Olive hatches for three weeks, trying to pick out the gray, rainy days that both the trout and the mayflies like. There’s always some urgency to this pre-runoff season, because it can turn sour at a moment’s notice as it did in April. The weather was still fine for fishing in a hood-up-on-the-rain-slicker sort of way, but after days of snow and rain the water was high, muddy, and cold, so the hatches would be off for a while. This was still too early for the seasonal melting of the mountain snowpack that swells the rivers with muddy ice water and blows six to eight weeks of fishing, but these shoulder seasons are short enough as it is, and you hate losing days to temporary storm runoff.

It had started beautifully back in late March, when we drove to the South Platte River thinking it might not be too early for Olives. I’d already been out a few times, starting in February at the inlet to a nearby reservoir, where I snaked my casts between chunks of dislodged shelf ice and managed some holdover stocked rainbows. This spot gets crowded later in the season, but that day I had it to myself except for a lone dog walker who gave me a look you’d normally reserve for someone fishing in a bathtub.

I was having an awful time with my knots. I hadn’t forgotten how to tie them over the winter, but I was rusty, so my loops went cattywampus, my bitter end had a mind of its own, and my frozen fingers felt like they belonged to a corpse, but those were still my first trout of the new year, so things were looking up.

I got out a few more times after that—and fishing really is like riding a bike—so by the time I went to the South Platte I had my river legs again. I drove down with one friend and met another on the river, and we caravanned miles downstream out of the crowd to a stretch that’s not fished as hard. There are no actual secrets on a popular tailwater an hour’s drive from Denver, but there is water that’s overlooked by some fishermen, and you wouldn’t mind keeping it that way. So when you’re playing a trout here and a car passes on the county road, you’re torn between holding the bent rod high to show off and acting like you’ve accidentally hooked a bush.

The Olives came off around one o’clock, and I found three fish rising in a short glide: two smaller ones in open water and what looked like a bigger one tucked in beside a rock. I tried one of the smaller fish first to see if I’d guessed right on the fly pattern. Blue-Winged Olives are a ubiquitous western hatch that comes off both spring and fall, so like most regional fishermen I carry no fewer than half a dozen different Olive patterns. My go-to is still the old quill-bodied parachute that now seems as dated but dependable as a Rolls-Royce, but if it always worked I wouldn’t have to carry the others. One of the smaller fish ate a size-20 parachute on the third or fourth cast, but the little hook didn’t bite, and the commotion of the missed strike spooked both fish. At least it was the right fly.

I waded into position for the trout that was still rising next to the rock. He was holding in a four-inch-wide tongue of current that had begun as melting snow in the mountains and was now hurrying toward the main branch of the Platte in Nebraska, then to the Missouri, then the Mississippi, and on to the Gulf of Mexico. Once there some of it would evaporate, join an upslope front, and fall as mountain snow again, endlessly repeating the cycle. This is the same water we’ve always had—brought by comets billions of years ago, they say—and it’s the only water we’ll ever have, but for the moment this global system was reduced to the eighteen inches of dead drift I’d need to get that trout to eat my fly—which it did. I didn’t have a landing net that day, but managed to beach him gently and release him: a fifteen-inch wild brown, fat for his length and a real specimen. Then I went looking for another one.

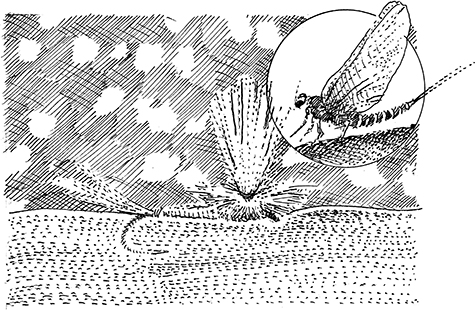

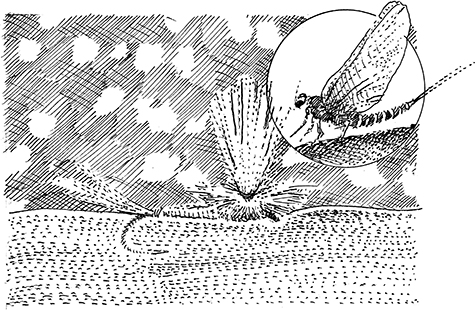

No hatch I know of depends more on weather than Blue-Winged Olives. These drab little mayflies like to emerge on cold, gray, wet days, which are coincidentally the same days that make the brown and rainbow trout in these tailwaters more eager to feed at the surface. So clouds are good, drizzle is ideal, and light rain is fine, although an outright downpour will put off the hatch for at least as long as it lasts, and sometimes longer. And Olives don’t mind snow, which explains the stories you’ll sometimes hear from people who saw a trout stream in a snowstorm and swore the fish were eating the flakes. On the other hand, both the trout and the mayflies cringe at direct sunlight like spelunkers emerging from a cave into a bright afternoon.

That day on the South Platte began with a thick overcast that got the hatch going nicely, but by midafternoon patches of blue began to blow over and sunlight burst onto the river, with predictable results. The hatching flies would immediately thin out, and the rises would sputter and stop in the time it takes to wake up from a dream and realize where you are. When clouds covered the sun again, it wasn’t like flipping a switch back on. It could take ten minutes for the bugs to get going, and another ten for the fish to notice and start rising again. When the sky clouded over for the last time in late afternoon, I understood that the hatch wouldn’t come back and ran into the rest of the crew as we were all walking back to the trucks. It’s hard to describe, but there’s a specific feeling of finality when the fishing is done for the day.

We made a few more trips to the South Platte in the next couple of weeks, and although the hatch petered off each time and we caught some fish, it was never as good as on that first afternoon. For one thing, the days we picked turned out to be no more than partly cloudy, so the bugs were sparse and the rises were spotty. For another, the water board kept bumping the flow out of Cheesman Dam, first from 65 cubic feet per second to 120, and then to 160. Any of those are perfectly good flows for dry-fly fishing if they’re stable, but trout can go off their feed when river levels rise suddenly. We say they get confused by the changing conditions and need a few days to acclimate. It’s as good an explanation as any.

Also, rising water dislodges lots of the gooey green aquatic vegetation fishermen incorrectly call “moss,” and when it’s thick it can foul your flies on every other cast until you start thinking about all the productive things you could have been doing if you’d stayed home.

After the worst of that April storm, when the power had come back on but the sky was still gray and drizzly, I drove up to the Big Thompson River below Olympus Dam. I hadn’t fished the Thompson since the previous fall, and then only out of curiosity. Like several other streams in the region—with my home water on the St. Vrain drainage at the epicenter—the Thompson took a hit in the flood of 2013, the result of a freaky September storm that dropped nineteen inches of rain in four days in a region that gets only twenty inches in a normal year.

The resulting flood was the kind of thousand-year event that rearranges the landscape overnight. It killed nine people, did millions of dollars’ worth of property damage, and washed out three state highways, stranding hundreds of us. It also scoured the steep stretches of my home stream down to the bedrock, depositing what had once been an aquatic insect habitat in new floodplains at the mouths of the canyons.

In the middle of it the river ran so thick with silt that it flowed less like water and more like syrup. I found dead brown trout strangled in mud on what was left of Highway 36. My own place was safe on high ground between the North St. Vrain and the Little Thompson, but recognizable parts of some of my neighbors’ houses were washing down the river.

Once the water receded and I could get out of the valley, I spent days locating friends. Some had been evacuated and were staying with friends or in church basements; others had hunkered down in places I couldn’t get into and they couldn’t get out of. Electricity, phone, and Internet had all been out for over a week, and there’s never been cell phone reception in the valley, so it wasn’t until I got out that I learned FEMA had listed all of us who’d been stuck north of the North Fork as “unaccounted for,” which those unfamiliar with the nomenclature of disaster took to mean missing or dead. So when I got a Wi-Fi signal at a coffee shop in a nearby town, I spent hours answering e-mails from friends and family to assure them I was alive. Most seemed happy to hear it.

I walked parts of the once-familiar riverbed in and around the small town of Lyons and wouldn’t have known where I was if it weren’t for the surviving landmarks. I met a man who said he was looking for unearthed gold nuggets and Indian artifacts and glanced with new interest at the sand at my feet. I met another man who was looking for his Prius. The flood had washed it out of his driveway, but the insurance company wouldn’t pay unless he could show them the damaged car, even though they knew full well that it was now buried under tons of sand and gravel, leaking gasoline, motor oil, and battery acid into the water table. (That was the first story I heard about someone being hung out to dry by their insurance company, but it wouldn’t be the last.) I said if I found the car, I’d call him. He reminded me that the phones didn’t work.

Over the next few weeks a kind of shrine developed in a vacant lot in town as people deposited found items that others might be looking for. Furniture, mailboxes, mismatched silverware, a coatrack, mounted deer antlers, a broken mirror, an empty picture frame, waterlogged family photos. Eventually the town board, in their infinite wisdom, took it all to the dump.

Emotions floated unexpectedly close to the surface. People who were calm, practical, and helpful for days would abruptly snap at nothing, and two weeks in, believing I was used to the new reality, I totally lost it at the sight of a piano wrapped around a cottonwood tree.

When it came to rebuilding, we all did what we could, using tools ranging from shovels to checkbooks. Some also dove down the preposterous rabbit holes of state and federal bureaucracies, only to emerge months later only partly successful and disillusioned by a system that seems stubborn about helping but eager to keep you from helping yourself. During the thick of it people had been anywhere from patient to helpful to heroic as conditions dictated, but as we waded on through the later stages of disaster—which resemble those of grief—a few surprising examples of shittiness emerged. Or maybe not so surprising. As a friend put it, “Those who were assholes after the flood had also been assholes before the flood.” On the plus side, a Larimer County sheriff’s deputy told me, “Ninety-nine percent of you folks have been a pleasure to deal with.”

During that first week or so when everyone was still cut off and in need of everything from firewood to food to drinking water to prescriptions to a generator to run a critical medical device, it had been the blue-collar types who had the tools, equipment, knowledge, and levelheadedness to do the heavy lifting. Later, when bumper stickers reading “Lyons Strong” and “We’ve Got Grit” began to appear, I proposed one that would say “Thank God for the Rednecks,” but no one else thought it was a good idea.

Which is to say, it was a long time before I started worrying about the fish.

Over the following winter the Corps of Engineers and the Department of Transportation charged in with heavy equipment and the best intentions and did more damage to the streams than the flood had done. In one spot healthy pine trees were cut from the bank of the stream so the logs could be used in “bank stabilization structures,” never mind that the root systems of live trees are better bank stabilization structures than anything you can build. And on the St. Vrain a Parks and Wildlife survey showed that the fish population had gone from 2,004 trout per mile before the flood to 798 after and then to nine trout per mile once the DOT and the Corps were finished with it.

I’d fished the Thompson once in October of the following year, when the road reopened thirteen months after the flood. I drove to the river on a day that was threatening snow and found parts of it looking like a cross between a gravel quarry and a landfill. A sparse Olive hatch petered off and I found a few rising trout, two of them in a run with a carpet spread out on the bottom of the pool and the remains of someone’s back porch piled up on the far bank. I did make a few casts, but my heart wasn’t in it.

When I went back this last time, six months later, the spring Olive hatch was a little heavier than it had been the previous fall—though still stingy by preflood standards—and there seemed to be a few more trout. Still, the fishing would have been disappointing if not for the apparent miracle of these few fish and the weightless little insects they were rising to surviving a flood that washed away a two-lane highway.

The hatch went off around four, and I thought about spending the rest of the day driving downstream to the little town of Drake and then up the North Fork to Glen Haven—both of which had been largely destroyed in the flood—but then decided against it. Disaster tourists usually come from somewhere else. When it all happened in your own backyard, you’ve already seen enough.

It started raining again in early May; another big storm predicted to bring a week’s worth of snow to the higher elevations and hard rain lower down. They’d kept bumping up the flow on the South Platte in sudden, unpredictable increments until it was finally unfishable, so four of us met up on the west slope between Aspen and Basalt. We rented a log house that was built in the 1880s as a stagecoach stop and had since been gussied up for tourists with a microwave and so many throw pillows there was hardly room to sit. This was a cozy place to eat, sleep, and kill our aimless time off the water. For instance, one night after supper one of the guys showed off a new app on his smartphone that would supposedly identify any music you played into it, and some smart-ass stumped it on the first try with an old Lightnin’ Hopkins tune. That kind of thing.

Three of the four of us had been in the flood, but it’s no longer a topic of conversation except as a time reference. It’s not that we’re all that stoic; it’s just that the well-meaning sympathy we got finally became embarrassing enough that when someone asked, “Were you in that flood?” we’d answer, “Aw, not really,” and change the subject. For that matter, after eighteen months we’d long since talked it to death among ourselves, including the part where we’d now have to travel farther from home to fish for the foreseeable future.

The day before I met the others at the cabin, the Colorado River upstream from Dotsero had gone from 950 cubic feet per second the afternoon before to 1,700 the next morning from rain and snow in the headwaters. I floated it with a friend anyway, since we were already there. Size-16 brown caddis flies were hatching in clouds and some Olives were floating around in the backwaters, but the river was the color and clarity of wet cardboard, so the trout couldn’t see them.

The Roaring Fork behind our rented cabin was in a little better shape, and we squeezed out a few trout on nymphs, but it was getting muddy, coming up fast, and wouldn’t last another day. It was getting harder to believe that this high water was just a temporary setback instead of the beginning of a big spring runoff that would end the early-season reprieve.

But the nearby Fryingpan River is a tailwater, so from the bottom-draw dam down to where Seven Castles Creek poured in brick-red, it was still low and clear, and we were happy to see it. At times like these I agree with my late friend Gary LaFontaine, who said that as a conservationist, he’d fight new dams on free-flowing rivers, but as a fisherman, he’d fish below them when they were inevitably built anyway.

The weather that week couldn’t have been better for the Olive hatch. It rained every day, but seldom hard enough to put down the hatch for more than a few minutes at a time. The ceiling of clouds was so low that you felt like you were standing in the sky, and the snow line reached halfway down the canyon, while along the river the dripping cottonwoods, dogwoods, and willows were leafing out and seemed to have gotten thicker and greener every time I looked up from the water. Now and then a hummingbird would buzz incongruously past in weather cold enough to see your breath. At odd moments you might wonder whether this was miserable enough to make you walk back to the truck and run the heater, but then you’d promptly forget about it.

The hatch came off between late morning and early afternoon each day and lasted for hours, with enough bugs on the water to get the trout feeding well, but few enough that they’d still pick your fly out of the crowd. For once it was like the fishing you imagine on the drive to the river but rarely find when you get there. (When you describe to a non-angler the kind of ideal conditions you’re always hoping for, they’ll ask, “Jeez, when do you ever get out?”)

Most of the trout we caught were the ten-inch browns that our friend Will at the fly shop in town says are overpopulating the river and should be thinned out, but there were enough bigger rainbows to keep you on your toes: sixteen to eighteen inches long, and one just over twenty-one inches—as measured against my landing net—that ate a size-20 Olive and tail-walked across the river, with its wide red stripe far and away the brightest thing in the landscape. Later one of my friends said, “That must have been a big trout, because you’re not usually one to whoop when you hook up.”

“Did I whoop?” I asked.

It was still raining when I got home from the Pan, and the North and South Forks of the St. Vrain were brown and foamy and out of their banks, although that’s not the benchmark it once was, because the river had rearranged the landscape, so the banks are no longer where they used to be. This turned out to not be as dire as it looked, but we were all a little skittish now, so sheriff’s deputies were stationed at the bridges for a few nights to keep an eye on the river, just in case.

I went down to look at the river myself and stood there wondering how I could so dearly love something that’s really just an example of water obeying the laws of physics. But a river running too high and muddy to catch trout on dry flies isn’t the worst that can happen, and, like everyone else I know, I had plenty of things to do besides go fishing; I just couldn’t think of any of them at the moment.