My first flight in a floatplane was in northern Canada sometime in the late 1970s. I don’t remember the exact year, but I remember the plane. It was a de Havilland Twin Otter: a big workhorse of an aircraft that carried ten fishermen, all our gear, a week’s worth of groceries and supplies, and a fifty-five-gallon drum of gas a hundred-some miles north to a lodge in the Northwest Territories. Flying in a floatplane had been a boyhood fantasy, so I tried to soak it all up: the aluminum ladder leading to the rounded hatch, the unforgiving tube-frame seats, the bulging cargo netting, all wearing the colorless patina of hard use. I peeked into the cockpit, where a pilot in coveralls was fiddling with mysterious knobs and hydraulic levers as the twin engines warmed up. I had no idea what I was looking at, but it was unbearably romantic in a steampunk sort of way.

The flight up there from Winnipeg had been another first. We were in a Douglas DC-3, the sausage-shaped, twin-engine tail-dragger you’ll recognize from old newsreel footage of paratroopers in World War Two and of the early days of commercial aviation, when flying was such a special occasion that women wore dresses and white gloves and men sported coats and ties. I peeked into the cockpit here, too (this was back in the days when you could peek into cockpits without getting arrested). If you’re old enough to remember the 1954 movie The High and the Mighty, the mother of all airline disaster films, you’ll understand why I expected to see John Wayne at the controls.

That old plane triggered the sense I still have that by flying into the far north I was traveling back in time to when people were industrious, uncomplicated, and self-reliant, and fish were fat, plentiful, and innocent. I’d become a writer by then, but hadn’t yet learned that the job was one of observation rather than an opportunity to grandstand, so I kept thinking things like, “Our hero strides aboard this ancient airplane without a thought for his own safety,” whereas in fact I was hoping this tin can could still get airborne. I mean, really, a car that old would have been in a museum.

That was a good trip. We caught big mackinaws and pike in the lake and fat grayling in the river, and I released what at the time would have been the world-record fly-caught lake whitefish without so much as a snapshot for proof. I also saw my first wolves. They seemed less like majestic symbols of wildness and more like stray dogs as they picked through the camp garbage, but they were, by God, genuine timber wolves!

I didn’t see any caribou, but so many of them migrated through there in the off-season—shedding their antlers as they went—that a normal spring chore was to collect the sheds and toss them on a pile in the middle of camp that by then had grown to a height of ten feet and looked like some kind of mute Stone Age monument.

Another spring chore was to straighten up a couple of graves on a rise overlooking the lake, resetting the sandblasted wooden crosses and crude board fences. These graves were maintained out of a free-floating sense of decency, even though no one knew for sure how old they were or who was buried there. Some claimed it was old French explorers; others said it was just a couple of trappers, and one of the guides elbowed me in the ribs and said they were unruly clients from last season. This was the kind of place you could reach only by floatplane.

A few years later, on a trip to Alaska, I flew in my first Beaver. A succession of three of them, actually, as a couple of us bounced from lodge to lodge on the kind of frenetic junket only a tourist bureau could dream up. Their conditions ranged from a fully refurbished purple number with white lightning bolts freshly painted down each side to a faded yellow one that was sound as a dollar mechanically but as dingy and threadbare inside as an old school bus. I’d never seen one of these in the flesh before, but they looked familiar from a childhood of leafing through dog-eared copies of Field & Stream and dreaming of fishing not with my uncle on a tame bass pond but with a bush pilot in trackless backcountry where I’d do battle with enormous, violent fish.

It turned out that a de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver with its beefy fuselage, 48-foot wingspan, and 982-cubic-inch Pratt & Whitney radial engine was several times more impressive in person than in photos. The planes were bigger than I expected, and the literally deafening roar of those engines said these aircraft meant business. After even a short flight my ears would continue to buzz for a while, and all sounds, from human voices to birdsong, seemed to be coming from underwater. The first time this happened there was a pleasant association that I couldn’t identify. Then I placed it as the same jittery excitement—half physical, half emotional—that I once felt when walking out onto a quiet city street with my ears ringing after a rock concert. I’ve since learned to wear foam earplugs on small planes to avoid permanently damaging my hearing.

There are lighter, faster, and sometimes even quieter floatplanes than Beavers, but as E. Donnall Thomas Jr. once wrote, something like a PA-18 Super Cub “couldn’t carry much more than one friend, our fly rods, and survival gear—fine for a fly-out day trip, but utterly inadequate to set up a two-week float.” I’ve been on Beavers that easily hauled a pilot, a guide, four fishermen, camping and fishing gear, a week’s worth of food, a small generator, gas cans, canoe paddles, and an outboard motor with room left over. A Beaver is the three-quarter-ton crew-cab pickup with a towing package to the Super Cub’s Audi sedan.

It’s not so much that Beavers make good bush planes as that they were specifically designed and built to be bush planes. They can get airborne in a gut-wrenchingly short space using sheer brute force and, according to factory specs, can carry a payload of up to 2,100 pounds. These planes are sexy-looking in the boxy, plainspoken way of a Conestoga wagon, which is to say their glamour derives entirely from where they can take you. That would be into roadless backcountry where the place-names may not be all that exotic but where you might be fishing with the person who named them. I once caught some beautiful brook trout from Victoria Creek in Labrador, and given Canada’s history with England, I asked if it was named after the former queen. My guide said, “No, I named it after my daughter—because they’re both pretty little things.”

We got to Victoria Creek in a Beaver operated by a flying service in Quebec called Air Saguenay. This was a striking fire-engine-red plane with a white tail suggesting spread wings and a racing stripe that resolved into the neck and head of a goose—the company’s logo. It was piloted by a French-Canadian named Pierre. He spoke no English and we spoke no French, so he just grinned and pantomimed the plane’s salient safety features in the order that you might need them: seat belts, fire extinguisher, first-aid kit, doors.

Pierre lived in a tent. I don’t mean that he sometimes stayed in a tent, he lived in one: a small canvas wall tent with a sheepherder’s stove for heat that he preferred over a bunk in the guides’ shack at camp, a room in town, or even his mother’s house, where he pitched the tent in the backyard over the winter, coming inside for showers and meals at the kitchen table. In all other ways he seemed perfectly normal.

One late afternoon as we broke down our gear after fishing, Pierre chunked up three of the Arctic char we’d killed, put them in a plastic tub with olive oil, lime juice, garlic, and chopped onion, and slipped them under one of the backseats, where the natural motion of the plane would keep the mixture agitated on the flight back from the river. In camp we ate this wonderful ceviche with saltine crackers, and since talking was pointless, we grinned and nodded as if we each thought the others were simpleminded. Leave it to a Frenchman to surmount a language barrier with good food—not to mention having olive oil and garlic within arm’s reach at all times.

I’ve also flown a few times on single-engine Otters. The de Havilland Otter is a later, larger version of the Beaver, with a longer wingspan, more horsepower, and a capacity of ten passengers—conceived as, and originally known as, the King Beaver. This is usually the plane that flies you into camp and that you don’t see again until it’s time to fly back out a week later, but I was at one high-occupancy lodge in the Canadian Arctic that had its own Otter on-site to rotate larger groups out to more remote camps.

The pilot told me that the previous year one of the fishermen had said he’d flown a similar Otter as a spotter in Vietnam—it had been equipped with wheels instead of pontoons then—and when they checked the ID numbers, the guy said that this was, in fact, the very same aircraft. It was a coincidence, but not an unbelievable one, since many of these planes have been passed from hand to hand for over half a century and can turn up anywhere. The pilot said the guy got sort of emotional. In a quavering voice he said, “I almost died in this plane,” but didn’t volunteer any details. Then he asked if he could fly it, just for old times’ sake, although of course, the camp’s liability insurance prohibited that.

But then the pilot added that he did let the guy sit up front, and I’d noticed for myself that the plane was equipped with dual controls. I got the distinct impression that if this sentimental vet had taken the yoke for a few minutes on a fly-out, the insurance company would never have known about it.

Fine for him, but as much as I love flying in floatplanes, I’ve never had the slightest hankering to operate one. Just being a passenger makes me feel plenty intrepid enough, and frankly, I’m not the kind of meticulous, technical guy who’d be good at it. Once a friendly pilot explained to me what all the controls in a Beaver did using language he wouldn’t have considered particularly technical. Afterward I nodded and asked, “But which one makes it go up?”

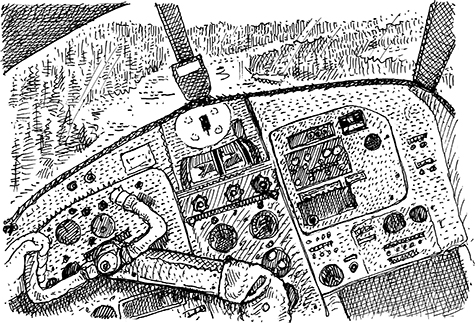

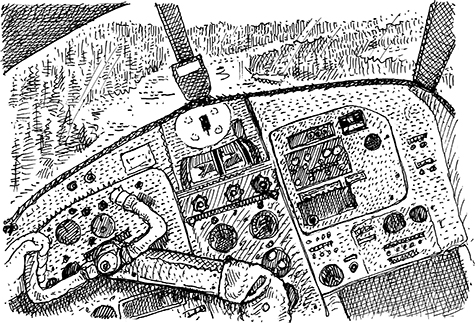

I did once briefly take the stick, though. We were flying out of a lodge in Alaska in a Beaver with dual controls, and I was sitting up front enjoying the view, trying not to touch anything, and thinking how much the instrument panel of this plane resembled the dashboard of a 1946 Plymouth. But the pilot, who was also a photographer, thought it would be a hoot to get a photo of me supposedly flying the plane, so he told me to take the yoke and hold it level while he shot frame after frame of me through a wide-angle lens. I never saw the photos, but I’m told they didn’t turn out. I was trying to act nonchalant, but I must have looked like I was facing a firing squad.

The first Beavers were made in 1947, and they went out of production a scant twenty years later in 1967. They’re so ubiquitous in the far north that it’s hard to believe that less than 2,000 were ever built—exactly 1,657, according to one source. There have been casualties over the years, but these things were built to last, and many are still in service somewhere in the world. You see them all over the place in Canada and Alaska, and some have been repaired, rebuilt, and upgraded so many times you wonder how much of the original aircraft remains. I was born in 1946, so I’ll never have the pleasure of flying in a Beaver that’s older than I am. The oldest one I’ve knowingly been in was built in 1952. That would have made it sixty years old at the time I was chauffeured around Kodiak Island in it in 2012, and it purred like a kitten, while virtually everything else produced in 1952 is now moldering in a landfill.

No one seems to know how many Beavers are still in use—“hundreds” is the best guess anyone is willing to make—but even with a limited and dwindling supply they’re everyone’s first choice for a floatplane, and a clean, low-hour Beaver can cost in the neighborhood of half a million dollars. A not-so-clean Beaver will run you less, but it can cost well into six figures to make it airworthy, not counting the staggering ongoing expenses of fuel, maintenance, and insurance. All of which means that many of those who love Beavers the most because they fly them every day can’t afford to own one: another item on life’s long list of injustices.

On the other hand, a pilot once told me that after a summer of flying sports in and out of remote fish camps he actually looked forward to the off-season when he could move back to town, with restaurants, movies, hot showers, clean sheets, and his long-suffering wife to cuddle with. He said he didn’t miss flying one little bit, but the assumption is that being a bush pilot is a calling as well as a job, and I couldn’t help but wonder if there were days when this guy would hear the drone of a single-engine prop plane and feel like an albatross with a broken wing. But maybe that’s just my tendency to shoehorn everything into the nearest available cliché. To me, climbing aboard a floatplane is either the beginning or the end of an adventure, but maybe to the pilot it’s just another day at work.

We now take it so much for granted that we forget what a recent development flying is. My maternal grandmother was born in 1881, only three generations ago, and twenty-two years before the Wright Brothers’ first flight. When she died in 1961, she’d managed to live her entire eighty years without ever getting on an airplane. Why? Because, she said, “If the Good Lord had intended for us to fly, He’d have given us wings.” When she traveled—which wasn’t often—she went by train. Apparently the Good Lord did intend for us to hurtle through the landscape at sixty miles an hour while sitting in a chair.

I don’t think she missed much, and she probably wouldn’t have gotten past security. (Grandma was the kind of dignified old lady who wouldn’t have stood still for being patted down by a stranger.) Flying in a commercial jet at thirty thousand feet isn’t especially fun, because you’re too high to see much beyond the geometric shapes of tilled fields, the smoggy sprawl of cities, or a wilderness of clouds; all amazing sights in their own right, but not what you’d call riveting. The view is so uninteresting that I try to get an aisle seat so I can stretch at least one leg and get to the bathroom without crawling over two other people. The best you can hope for from commercial flying is that the trip will be uneventful and they won’t lose your luggage.

But flying in a floatplane is flying the way it should be. You might be going a hundred miles an hour a hundred feet off the ground: low enough and slow enough to identify wildlife on the order of caribou, bears, moose, musk oxen, wolves, and even trumpeter swans. It’s a bird’s-eye rather than a god-like view. You’ll see rocky glacial eskers under the surface of lakes and think about the lake trout that are probably collected around them, and gaze strategically at the pools and riffles of feeder creeks. Every time I’ve seen pods of salmon in a river from the air, I’ve thought of the passage in Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea where Santiago thinks he’d like to ride in an airplane so he could fly over the ocean and look down at the fish.

Of course, as a responsible adult I now have the required misgivings about the obscene amounts of fossil fuel floatplanes burn, the air and noise pollution they produce in otherwise clean, silent places, the oil slicks they sometimes leave behind, and the knowledge that the second I land on a pristine lake or river, it becomes that much less pristine because of my presence. But even knowing now that it can never be entirely unambiguous, I always get the same rush when I walk down to a floatplane tied up at a dock, riding high on its pontoons and bobbing gently in the chop: this is the plane that will take me into the kind of wilderness where there’s too much water to go anywhere by land and too much land to get very far in a boat.

The way we use it now, “wilderness” is a word that has more to do with emotion than with a specific definition. Saying “wilderness” is like saying “great singer,” which could mean anyone from Luciano Pavarotti to Johnny Cash. But one thing it can mean is a region that’s still so vast, wet, roadless, and remote that you need a floatplane to get around in it. We go into places like that to catch wild fish, and for more personal reasons that may be complicated or as simple as the urge to escape the present—which admittedly looks none too promising—into, if not the actual past, then at least the kind of timelessness where life still makes sense.