2 Distancing from Truth

Veritism

In epistemology, the conviction that truth is vital is virtually axiomatic (see David, 2005). Although practical or prudential considerations might favor accepting an acknowledged falsehood, most epistemologists hold that it is never epistemically legitimate to do so. Call any position that takes truth to be necessary for epistemic acceptability veritism (see Goldman, 1999). It seems prima facie reasonable. But, I will argue, veritism is unacceptable. For, if we accept it, we cannot do justice to the epistemic achievements of science. Truth ought not be our paramount epistemic objective.

I begin this chapter with a sketch of veritism. My discussion is deliberately schematic because the weakness I focus on is endemic to truth-centered epistemology, being shared by internalist, externalist, virtue-theoretic, and knowledge-first positions. Too strong an emphasis on truth prevents epistemology from accommodating the cognitive contributions of science. But veritistic commitments run deep. Abandoning them requires radical revisions. In particular, I urge that belief, assertion, and knowledge should be sidelined in favor of acceptance, profession, and understanding. I show how this reconfigures the epistemic terrain, making available resources that veritistic positions lack. I go on to sketch a variety of devices that figure in science and philosophy, devices whose epistemic value comes to the fore if we distance epistemology from an inviolable commitment to truth.

According to veritism, truth-conduciveness is the appropriate standard of assessment for epistemic policies, practices, and their products. This holds for all epistemic achievements—knowledge, understanding, wisdom, know-how. The epistemic value of methods for obtaining and evaluating information, and the criteria used in such evaluations are purely instrumental. They are justified only because and only to the extent that they are truth-conducive. Replicability of scientific results, for example, is epistemically valuable only if replicable results are more likely to be true than irreplicable ones. Should it turn out that replicable results are no more likely to be true than otherwise well supported irreplicable results, replicability would have no epistemic value. As Berker notes, the shape of this argument is familiar. Veritism, he argues, is a form of consequentialism. It differs from more familiar consequentialist positions in that the consequence it wants to promote is true belief or a preponderance of true belief over false belief, not a preponderance of, as it might be, pleasure over pain or utility over disutility (Berker, 2013). If veritists are right, then at least insofar as our ends are cognitive, we should accept only what we consider true, take pains to ensure that the claims we accept are in fact true, and promptly repudiate any previously accepted claims upon learning that they are false.

Following William James (1951), many veritists hold that our overriding cognitive objective is to believe as many truths as possible and disbelieve as many falsehoods as possible (e.g., Alston, 1988, 258; Goldman, 1999, 5; Lehrer, 1986, 6; BonJour, 1985, 9). This is the objective with respect to each and every individual contention. It is, they say, never legitimate to accept an acknowledged falsehood, even if so doing would in the long run result in the acquisition of more or a higher proportion of true beliefs than the repudiation of that falsehood would (Firth, 1981).

As stated, Jamesian veritism is remarkably tolerant. It does not discriminate among true (or false) beliefs. Insofar as our goals are purely cognitive, it says, we should amass as many truths and as few falsehoods as possible. This is easily done. Take any number. Add two. Do it again. And again. And again. With each iteration you get another truth. Your risk of accepting a falsehood along the way is vanishingly small. Should you prefer to restrict yourself to the empirical realm, take any trivial truth, such as ‘Cats don’t grow on trees’. Add a disjunct. (Its truth-value doesn’t matter.) Add another disjunct. And another. You now have numerous true beliefs. This is far easier and far less risky than, for example, mounting a carefully controlled, scrupulously executed, theoretically grounded experiment. Nevertheless, running the experiment is epistemically more valuable. It won’t do to insist that the experiment is likely to be more fruitful, at least if the only available way to measure fruitfulness is to count the number of true conclusions or the proportion of true over false conclusions that can be drawn. Every proposition has infinitely many consequences—indeed, infinitely many obvious consequences—so the fruits of trivial inferences and those of the well-run experiment are on a par. And the automaticity of the procedure for generating trivial bits of knowledge is efficient enough to dwarf the number of truths one could discover by devising and running experiments.

As many epistemologists recognize, this suggests that the Jamesian goal needs to be fine-tuned. Rather than considering all true beliefs on a par, perhaps epistemology should distinguish between significant and trivial truths, or between truths obtained by significant and trivial means. Then the Jamesian veritist could insist that our goal is to believe as many significant truths as possible and to disbelieve as many significant falsehoods as possible, or perhaps to believe as many significant truths as possible and to disbelieve as many falsehoods as possible, whether or not they are significant (since it seems epistemically objectionable to believe falsehoods even if they are trivial). Alternatively, he could hold fast to the veritist goal as a purely cognitive end, but recognize that as finite beings with limited resources, we need, for practical reasons, to prioritize some truths over others.

Not all veritists are Jamesians. Pritchard focuses on a position he calls ‘Epistemic Value T-Monism’, the view that “true belief is the sole fundamental epistemic good” (2010, 14). For the T-Monist, the Jamesian concern with proportionality drops away or becomes of merely instrumental value. We should, on the T-Monist view, worry about false beliefs only if harboring them somehow interferes with our amassing true beliefs. Sosa (2007) credits only aptly formed true beliefs—those that emerge from the proper use of our epistemic competences.

Treanor goes further. He disputes the egalitarianism inherent in the Jamesian position, arguing that it rests on “the implicit assumption that any two truths contribute the same amount of truth to the balance sheet” (2013, 599). This, he claims, is incorrect. Rather than being concerned with how many truths someone believes, we should be concerned with how much truth he believes. And the latter is not a function of the former. Trivial truths, Treanor argues, contribute little to a person’s overall body of true belief; significant truths contribute a great deal. Undermining the idea that we need to (or even that we can) count and aggregate true beliefs sidelines the triviality worry. Still, Treanor remains a veritist. Like his Jamesian opponents, he thinks that truth is epistemically central.

So does Hetherington (2011). He maintains that we should take the locution ‘knowing better’ seriously, and recognize that knowledge admits of degrees. If an epistemic agent’s belief that p is true, she knows that p in a minimal way; if she has some justification for p, she knows better that p; and if she can defeat skeptical challenges to p, she knows perfectly well that p. But even the most minimal sort of knowledge requires truth. Epistemic gradualism does not solve our problem.

Most veritists take knowledge to be the paradigm of epistemic success, where knowledge is nonfortuitously justified or reliable true belief. Some consider knowledge valuable for its own sake. Others think that the valuable aspect of knowledge lies in its embodying true belief. Either way, the reason to favor justified beliefs (those backed by sufficient evidence) and safe beliefs (those that could not easily have been false) is that they are liable to be true. Justification and safety are of merely instrumental value. Since propositions are the contents of beliefs and the bearers of truth-values, they are what is known.1 If this is right, the sort of justification of interest to epistemology is in the first instance the justification of individual propositions. To justify a given proposition is either to infer it from already justified propositions or to show how belief in it emerges from reliable belief-forming mechanisms. S is justified in believing p on the basis of q, and q on the basis of r, and so on. On some accounts the sequence ends in propositions that need no further justification (Fumerton, 2010); on others, the sequence is infinite (Klein, 1999).

Holists are apt to consider this picture misleading. They maintain that epistemic acceptability is, in the first instance, acceptability of a fairly comprehensive theory, or system of thought—a constellation of mutually supportive commitments that bear on a topic. Let us call such a constellation an account.2 It consists of contentions about a topic and the reasons adduced to support them, the ways they can be used to support other contentions, and higher-order commitments that specify why and how evidence supports them. It also contains normative and methodological commitments specifying the suitability of categories, the criteria of justificatory adequacy, and the ways to establish that the criteria have been met. An account’s priority over its components is epistemic, not historical. There is no contention that people come to accept an account before coming to accept the various items that comprise it. Rather, the claim is that, regardless of the order in which they are acquired, commitments are epistemically justified only when they coalesce to constitute a tenable account. An account as a whole is tenable just in case it is as reasonable as any available alternative in light of the current relevant antecedent commitments (Elgin, 1996). The acceptability of individual claims, as well as of methods and standards, is derivative, stemming from their role in a tenable account. Perhaps a linear model of justification works for the belief that the cat is on the mat, but disciplinary understanding is holistic. The claim that electrons have negative charge is justified only to the extent that the scientific account that embeds it is.

As standardly construed, knowledge is granular: it comes in discrete bits. The objects of knowledge are individual facts, expressed in true atomic propositions or stated in true atomic declarative sentences. Judy knows (the fact) that the bus stops at the corner; George knows (the fact) that cows eat grass. Each grain of knowledge is supposed to answer to a separate fact. An epistemic agent acquires knowledge by amassing grains. To be sure, one grain can support another. Much of our knowledge is a product of inference from other things we know. But the unit of knowledge is an individual sentence, belief, or proposition—something that apparently bears a truth value in isolation. The commitment to granularity is manifest in the widespread adherence to Jamesian veritism. Indeed, the Jamesian goal is unintelligible unless we suppose that knowledge comes in discrete, countable bits (Treanor, 2013).

Disciplinary understanding is not an aggregation of separate, independently secured statements of fact; it is an integrated, systematically organized account of a domain. There is no prospect of sentence-by-sentence verification or sentence-by-sentence justification of the contentions that comprise a disciplinary account, for most of them lack separately evaluable consequences. Independent of an account of heat transfer, nothing could count as evidence for or against the claim that a process is adiabatic. Independent of an ethological theory, nothing could count as evidence for or against the claim that grooming behavior manifests reciprocal altruism. Collectively the components of an account are apt to have testable implications; separately they do not. In Quine’s words, they “confront the tribunal of sense experience not individually but only as a corporate body” (1961, 41). Nor is the problem merely epistemic. Some scientific statements evidently lack truth-values in isolation. If the individuation of the items they purport to refer to—a species, a retrovirus, or a lepton, for example—is provided by an account or cluster of accounts, there may be no fact of the matter as to whether such statements are true independent of the epistemic adequacy of the account or cluster that characterizes them.

If it is to accommodate the cognitive contributions of the disciplines, epistemology should be holistic, construing the primary unit susceptible of justification to be a more or less comprehensive account of a topic rather than an individual proposition. Elements of such an account then are justified largely by their contribution to a coherent, relatively comprehensive body of thought. ‘Knowledge’ is usually taken to pertain to discrete propositions. An epistemic agent knows that p. Tenable accounts are said to afford an understanding of their topics. This suggests that epistemology should shift its focus from knowledge to understanding, or at least broaden its focus to comprehend understanding as well as knowledge. By itself, this should not spark panic among epistemologists. But, I maintain, a greater revision is called for. To accommodate science, epistemology must relax its commitment to truth. I will argue that the relation between truth and epistemic acceptability is both more tenuous and more circuitous than is standardly supposed. It is often epistemically responsible to prescind from truth to achieve more global, and more worthy cognitive ends.

At first blush, this looks mad. To retain a commitment to a falsehood merely because it has other epistemically attractive features seems the height of cognitive irresponsibility. Allegations of intellectual dishonesty, wishful thinking, false consciousness, or worse immediately leap to mind. But science routinely transgresses the boundary between truth and falsity. It smooths curves and ignores outliers. It develops and deploys simplified models that diverge, sometimes considerably, from the phenomena they purport to represent. It subjects artificially contrived lab specimens to forces not found in nature. It resorts to thought experiments that defy natural laws. Even the best scientific accounts are not true. Not only are they plagued with anomalies and outstanding problems, but where they are successful, they rely on lawlike statements, models, and idealizations that are known to diverge from the truth. Veritism might reasonably be undaunted by the existence of anomalies and outstanding problems, since they are readily construed as defects. The more serious problem comes with the laws, models, and idealizations that are acknowledged not to be true but that are nonetheless critical to, indeed at least partially constitutive of, the understanding that science delivers.

Consider the problem that models pose. The ideal gas law, pV = nRT, represents the relation between pressure, volume, and temperature in a gas comprised of dimensionless, spherical molecules that exhibit no mutual attraction. There is no such gas; indeed, if our fundamental theories are even nearly right, there could be no such gas. All material objects have spatial dimensions. Being subject to gravity, all attract one another. No molecules are spherical. Nonetheless, the ideal gas model is integral to thermodynamics. To be sure, there are more refined models, such as the van der Waals equation and the virial equation, that incorporate some of the features of actual gases that the ideal gas model omits; but they too are idealizations, not accurate representations of any actual gas. Yet these models, which are true of nothing real, figure in a genuine understanding of how actual gases behave.

Thought experiments should also vex the veritist. They are not actual experiments and often not even possible experiments. Einstein demonstrated the equivalence of gravitational mass and inertial mass by inviting scientists to compare the experience of a person riding in an elevator in the absence of a gravitational field and her experience while at rest in the presence of a gravitational field. Lacking external cues, she could not tell which situation she was in. To actually run the experiment we would need to place an unconscious subject in a windowless enclosure, send her to a region of outer space distant from any significant source of gravity, restore her to consciousness, and query her about her experiences. This is morally, practically, and physically unfeasible. It is evidently also unnecessary. Physicists take the thought experiment by itself to establish the equivalence.

Far from being defects, models, idealizations, and thought experiments figure ineliminably in successful science. If truth is mandatory, much of our best science turns out to be epistemologically unacceptable and perhaps intellectually dishonest. Our predicament is this: We can retain the truth requirement and construe science either as cognitively defective or as noncognitive, or we can reject, revise, or relax the truth requirement and remain cognitivists about and devotees of science.

I take it that science provides an understanding of the natural order. By this I do not mean merely that an ideal science would provide such an understanding or that at the end of inquiry science will provide one, but that much actual science has done so and continues to do so. I take it, then, that much actual science is cognitively reputable—indeed, estimable. So an adequate epistemology should explain what makes good science cognitively good. Too strict a commitment to truth stands in the way. Nor is science the only casualty. In other disciplines such as philosophy, history, political science, and economics, as well as in everyday discourse, we often convey information and advance understanding by means of sentences and other representations that are not literally true. An adequate epistemology should account for these as well.

A tenable account is a tapestry of interconnected commitments that collectively constitute an understanding of a domain. My thesis is that some representations that figure ineliminably in tenable accounts make no pretense of being true, but are not defective on that account. Indeed, I will argue, their deviations from truth are epistemically valuable—often more valuable than the unvarnished truth about the phenomena would be. If I am right, tenable accounts and the understandings they embed have a more intricate symbolic structure than epistemologists standardly suppose. Nevertheless, I do not think that we should jettison concern for truth completely. The question is what role a truth commitment should play in a holism that recognizes a multiplicity of sometimes conflicting epistemological desiderata.

Stepping Back

Consensus has it that epistemic acceptability requires something like nonfortuitously justified and/or reliable, true belief. The justification, reliability, and belief requirements involve thresholds. The connection between the belief’s being true and its being justified or reliable should not be due to (the wrong kind of) luck (see Pritchard, 2010). But truth is supposed to be an absolute matter. Either a belief content is true or it is not. I suggest, however, that the so-called truth requirement on epistemic acceptability involves a threshold too. I am not saying that truth itself is a threshold concept. Perhaps such a construal of truth would facilitate treatments of vagueness, but that is not my concern. For my purposes, classical bivalence is acceptable. Either a sentence, belief, or proposition is true or it is false. My point is that epistemic acceptability turns not on whether it is true, but on whether it is true enough—that is, on whether it is close enough to the truth. “True enough” obviously has a threshold.

This raises a host of questions. But before addressing them, let me issue a disclaimer. I do not deny that (unqualified) truth is an intelligible concept or a realizable ideal. We readily understand instances of the (T) schema:

‘Snow is white’ is true ≡ snow is white

‘Power corrupts’ is true ≡ power corrupts

‘Neutrinos have mass’ is true ≡ neutrinos have mass

and so on. So long as it evades the paradoxes, a disquotational theory of truth suffices to show that the criterion expressed in Convention (T) can be satisfied. One might, of course, want more from a theory of truth than satisfaction of Convention (T); but to make the case that the concept of truth is unobjectionable, any minimalist theory that does not engender paradox suffices. Moreover, we can often tell whether a sentence is true. We are well aware not only that

‘Snow is white’ is true ≡ snow is white,

but also that

‘Newly fallen snow is white’ is true.

The intelligibility and realizability of truth, of course, show nothing about which sentences are true or which truths we can discover. Nevertheless, as far as I can see, nothing about the concept of truth discredits veritism. Since truth is a self-consistent, intelligible concept, it is open to epistemology to insist that only truths are epistemically acceptable. Since truth is a realizable objective, such a stance does not lead inexorably to skepticism. I do not deny that veritism is an available epistemic stance. But I think it is an unduly limiting one. It prevents epistemology from accounting for the full range of cognitively estimable achievements.

If epistemic acceptance is construed as belief and epistemic acceptability as knowledge, the truth requirement seems reasonable (see Wedgwood, 2002). For cognizers like ourselves, there seems to be no epistemically significant gap between believing that p and believing that p is true. Ordinarily, upon learning that his belief that p is false, an epistemic agent ceases to believe that p. Moreover, he considers it epistemically obligatory to do so. One ought to believe only what is true. If he cannot manage to divest himself of the belief, he considers his failure a defect in his epistemic character. Perhaps a creature without a conception of truth can harbor beliefs. A cat, lacking the capacity for semantic ascent, might believe that there is a mouse in the wainscoting without believing that ‘There is a mouse in the wainscoting’ is true.3 In that case, the connection between believing that p and believing that p is true is not exceptionless. But whatever holds for cats, it does not seem feasible for any creature that has a conception of truth to believe that p without believing that p is true. If epistemic acceptance is a matter of belief, acceptance is closely linked to truth (Adler, 2002). So is assertion. Although asserting that p is not the same as asserting that p is true, it seems plain that one ought not to assert that p if one is prepared to deny that p is true or to suspend judgment about whether p is true; nor ought one assert that p is true if one is prepared to deny that p or to suspend judgment about whether p. Assertion and belief, then, seem committed to truth. Knowledge shares that commitment (Williamson, 2000). Whether or not knowledge is equivalent to justified or reliably generated true belief, once someone discovers the falsity of something she took herself to know, she withdraws her claim to knowledge. She says, ‘I thought I knew it, but I was wrong’, not ‘I knew it, but I was wrong’.

Being skeptical about analyticity, I do not contend that a truth commitment is part of the meaning of ‘belief’, ‘assertion’, and ‘knowledge’. Nor, for my purposes, does it matter whether belief is more primitive than knowledge or vice versa. Whatever the details, the truth commitment tightly intertwines with our views about belief, assertion, and knowledge. It seems best, then, to retain that connection and revise epistemology by making compensatory adjustments elsewhere. Once those adjustments are made, knowledge and belief turn out to be less central to epistemology than we standardly think.

I do not then claim that it is epistemically acceptable to believe what is false or that it is linguistically acceptable to assert what is false. Rather, I suggest that epistemic acceptance is not restricted to, and does not always involve, belief. L. Jonathan Cohen distinguishes between acceptance and belief. With some modifications, I deploy his distinction. According to Cohen, “belief that p is a disposition, when one is attending to issues raised or items referred to by the proposition that p, normally to feel that it is true that p and false that not-p, whether or not one is willing to act, speak, or reason accordingly.… To accept that p is to have or adopt a policy of deeming, positing, or postulating that p” (1992, 4). The term ‘belief’ is ubiquitous in epistemology. To avoid (or at least minimize) confusion, I will use the term ‘conviction’ for what Cohen calls ‘belief’. To be convinced that p is to be disposed, when attending to issues raised or items referred to by p, normally to feel that it is true that p and false that ~p. To accept that p involves being willing to take p as a premise, as a basis for action or, I add, as an epistemic norm or a rule of inference, when one’s ends are cognitive. This includes being willing to give others to accept that p via testimony. Acceptance is not a disposition to represent, but a disposition to act. I impose two restrictions: first, I am concerned only with cases where our ends are cognitive. So I set aside cases where acceptance is purely prudential, practical, self-destructive, or whimsical. Second, I restrict acceptance to assertoric—that is, non-reductio—inferences, and to actions that are not intentionally self-defeating (these being the practical counterparts of reductio inferences). I grant that reductios are cognitive and that in making a reductio argument we temporarily accept a premise in order to demonstrate that it is unacceptable. But reductios are not the sorts of inferences that concern me, since acceptance-for-reductio is too short-lived to serve my purposes.

Something more is required. An epistemic agent who accepts a consideration is not just willing to deploy it when her ends are cognitive; she is also able to do so. Someone who, on the basis of testimony, believed that modus ponens is a valid rule of inference, but had no idea how or when to apply it, would not be in a position to accept modus ponens. In my usage, then, to accept that p is to be willing and able to take p as an assertoric premise, epistemic norm or rule of inference in one’s reasoning or as a basis for action when one’s ends are cognitive. To reject that p is to accept that not-p. To withhold that p is to fail to accept that p and fail to accept that not-p. Acceptance is action oriented in a way that conviction per se is not. In what follows I will continue to use the term ‘belief’ as it is standardly used, to cover cases where conviction and acceptance align.

Although there is considerable overlap, acceptance and conviction can diverge. One can be convinced of propositions that in a given context one does not accept. All snakes in Australia are venomous. So an Australian might find that she can’t help but feel that every snake she sees is venomous. She is convinced. Nevertheless, she may train herself to accept that the garter snakes she encounters in Maine are harmless. She does not call the animal control officers each time she sees a garter snake slither across the campground. Conversely, people often accept things of which they are not, or not yet, convinced. They accept propositions for the purposes of argument or as a working hypothesis, and draw out their consequences. Judah Folkman suspected that cancer can be suppressed by inhibiting angiogenesis in tumors. If tumors lack an adequate blood supply, he reasoned, they will be unable to grow. Initially, this was only a suspicion. He accepted it as a working hypothesis, drew inferences, and designed experiments based on it. When the long series of experiments yielded the results he anticipated, he became convinced. But the acceptance was earlier, and independent of the conviction (Folkman, 1996).

The term ‘working hypothesis’ is multiply apt here. A working hypothesis is a hypothesis that a scientist works with; it is not an idle hunch. It does some work for him, framing and focusing his investigation. And it is accepted only so long as it works—so long, that is, as it is epistemically fruitful. I contend that acceptance rather than conviction is epistemologically central. The Australian camp counselor is saddled with a conviction that she recognizes is unwarranted. It is too ingrained for her to easily give up. This is unfortunate. But if she manages to bracket it and accept that many North American snakes are harmless, she is not epistemically defective.

The shift from belief to acceptance requires an additional shift, for belief is closely tied to assertion. Since I contend that much of our cognitively responsible verbal outputs concerns acceptance rather than belief, I cannot comfortably hold that that output consists in assertions. I maintain that uttering or inscribing seriously and sincerely for cognitive purposes—call it ‘professing’—is not limited to asserting. We regularly reason verbally within the parameters of accounts we are not convinced of. Atheist philosophers profess ‘God exists and is not a deceiver’ in discussions of Descartes. Nominalists profess the Theory of Forms in discussions of the divided line. Physicists profess ‘F = ma’ in discussions of slow-moving middle-sized physical interactions, even though they consider Newton’s laws to have been superseded.

Some might maintain that what I have called professing is just a matter of pretending. On such a view, in discussing the Sixth Meditation, I pretend that I am convinced by Descartes’s proofs for the existence of God and reason within the pretense. In discussing the motion of the billiard ball, I pretend that F = ma. But professing is not the same as pretending. Moore’s paradox is an assertion of the form ‘p but I do not believe that p’. To assert that p is to put it forth as something one believes. To assert that one does not believe that p is to deny that one believes that p. So there is something absurd or self-defeating about asserting a Moore’s paradoxical sentence. The paradox cannot be avoided by retreating to pretense. An actor on stage saying, ‘Buckingham is loyal to the king’ pretends to be asserting that Buckingham is loyal to the king. But if, without breaking character in the middle of his speech, the actor were to say, ‘Buckingham is loyal to the king but I do not believe that Buckingham is loyal to the king’, his utterance would be as absurd and self-defeating as a standard Moore’s paradoxical assertion. Similarly, a child having a make-believe tea party might pretend that her toy dog Mopsy says, ‘I want another cookie’. But if she were to pretend that Mopsy says, ‘I want another cookie, but I do not believe I want another cookie’, her pretend-utterance would be equally absurd and self-defeating (Szabó, 2001).

To pretend to assert that p is to act as if one had asserted that p. But to profess that p is to do something different. It is to make p available to function as a premise or rule of inference in a given context for a given cognitive purpose. If one is professing rather than asserting, there is nothing absurd about saying, ‘God exists and is not a deceiver but I do not believe that God exists and is not a deceiver’. In fact, it may be a good way of signaling that ‘God exists and is not a deceiver’ is professed but not asserted in a particular context. As Cohen (1992, 72–73) argues,

where an utterance of ‘It is raining’ implies acceptance that it is raining but not belief that it is raining, there should be no feeling of oddness or anomaly. And in fact it is not at all difficult to imagine such cases with more complex structures as in

“All right. Your arguments from economic theory are unanswerable and I have to concede your point. Index-linked wage settlements are inflationary. But, although I am bound to accept this, and everything that follows from it, I still don’t really believe [= I am still not really convinced] that index linked wage settlements are inflationary.”

As so often in linguistic analysis, a larger slab of discourse constrains us to suppose a speech-act is different from the one that a smaller one suggests.

The close connection between the conviction that p and the conviction that p is true explains why conviction and belief are in general impervious to the will (Williams, 1973).4 A conviction is true only if things are the way its content represents them to be. Fred’s conviction that it is raining is true only if it is in fact raining. But if his conviction were responsive to his will—if, that is, wishful thinking were an effective mechanism for forming convictions—by willing, wishing, or desiring strongly enough, he could convince himself that it is raining even if it is not, and even if he as ample evidence that it is not. Self-deception is real, so the imperviousness in question is not absolute. But self-deception is difficult to sustain. For it is hard to retain a conviction that flies in the face of one’s evidence, while continuing to hold one’s other convictions firm (see Adler, 2002). Normally we find ourselves convinced of one thing or another. Sometimes, to be sure, we become convinced through arduous investigations or laborious chains of reasoning. But even in these cases, the fruits of our cognitive labors seem to simply emerge from the labor. They do not present themselves as a matter of choice.

This creates a conundrum for epistemology. On the one hand, we do not want to claim that it is up to an epistemic agent whether to believe a proposition for which she has and recognizes that she has sufficient evidence. On the other hand, epistemology is a normative discipline. It is given to issuing pronouncements about what epistemic agents should believe in various circumstances. If we are passive with respect to belief, then the ‘should’ seems impertinent. If Fred can’t help but believe what he does, it’s no use telling him that he should believe something different (or, for that matter, telling him that he should keep believing what he does). What he believes is not up to him.

Here the distinction between conviction and acceptance is helpful. Conviction is passive. As Fred surveys the arid landscape, he can’t help but be convinced that it is not raining, however much he might wish it were. But acceptance involves agency. Even if it is impertinent to criticize epistemic agents for convictions they cannot help but harbor, it is not impertinent to criticize them for the premises and rules of inference that they accept. For acceptance is voluntary. And it is reasonable to ask whether, or to what extent, the acceptance of a given premise or rule furthers the agent’s cognitive objectives. Fiona can decide to accept the proposition that Amherst is 90 miles from Boston, and use it as a basis for reasoning about Massachusetts geography. In so doing, she need not think the proposition is true. She need only think it is true enough for her current purposes. Rather than assuming that as a matter of fact Amherst is exactly 90 miles from Boston, she deems the distance close enough to 90 miles that it does no harm to identify the actual distance, whatever it is, with 90 miles. To identify a with b is not to hold that a is identical to b. It is to hold that in the given circumstances it does no harm to treat a and b as identical (Goodman, 1977).

This is not to suggest that any consideration whose acceptance would cause one to realize one’s cognitive objectives or increase the probability of doing so is thereby acceptable. But a consideration whose integration strengthens the tenability of an account has, for that reason, a claim to acceptability.

Felicitous Falsehoods

Understanding is often couched in and conveyed by symbols that are not true. Many of them do not even purport to be true. Such symbols are epistemically felicitous falsehoods.5 Not all scientific models are propositional. Besides equations and verbal models, science is rife with diagrams, such as harmonic oscillator depictions in physics texts, three-dimensional models such as tinker-toy models of proteins, real-life simulations, and computer-based simulations. Nonpropositional models and diagrams are not, strictly speaking, false. But if interpreted as realistic representations of their referents, they are inaccurate in much the same way that false descriptions of an object are inaccurate. All represent their referents as they are not. So despite the fact that it is a bit of a misnomer, for ease of exposition, I label all such models falsehoods; if despite (or even because of) their inaccuracy they afford epistemic access to their objects, they are felicitous falsehoods.6 I contend that we cannot understand the cognitive contributions of science, philosophy, or even our everyday accounts of things, if we fail to account for the epistemic functions such symbols perform.

Here are some familiar cases:

Curve smoothing: Ordinarily, each data point on a graph is supposed to represent an independently ascertained truth. (The temperature at t1, the temperature at t2,…) By interpolating between and extrapolating beyond these truths, we expect to discern the pattern they instantiate. If the curve we draw connects the data points, this is reasonable. But the data rarely fall precisely on the curve adduced to account for them. The curve then reveals a pattern that the data do not instantiate. Strictly, it seems, veritism requires accepting the data only if we are convinced that they are true, and connecting these truths to adduce additional truths. In that case, the line should connect all the data points no matter how convoluted the resulting curve turns out to be. This is not done. To accommodate every point would be to abandon hope of finding order in most data sets, for jagged lines and complicated curves mask underlying patterns and regularities. Nevertheless, it seems cognitively disreputable simply to let hope triumph over experience. Surely we need a better reason to skirt the data and ignore the outliers than the fact that otherwise we will not get the kind of theory we want. Nobody, after all, promised that the phenomena would obligingly accommodate themselves to the kind of account we want.

We often have quite good reasons for thinking that the data ought not, or at least need not, be taken as entirely accurate. Sometimes we recognize that our measurements are relatively crude compared with the level of precision we are looking for. Then any curve that is within some δ of the evidence counts as accommodating the evidence. Sometimes we suspect that some sort of interference throws our measurements off. Then in plotting the curve, we compensate for the alleged interference. Sometimes we are confident that the measurements are accurate, but think the phenomena measured are complexes only some of whose aspects concern us. Then in curve smoothing we, as it were, factor out the irrelevant aspects, construing them as noise. Perhaps with a bit of hand-waving, veritism could accept such rationales for smoothing curves. Sometimes, however, we have no explanation for the data’s divergence from the smooth curve. But we may correctly judge that what matters is the smooth curve the data indicate, not the jagged curve they actually instantiate. Whatever the explanation, we accept the curve, taking its proximity to the data points as our justification. We ignore the outliers, thinking that there is something-we-know-not-what unacceptable about them. We understand the phenomena as displaying the pattern the curve marks out. We thus dismiss the data’s deviation from the smooth curve as negligible.

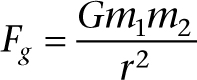

Ceteris paribus claims: Many lawlike claims in science obtain only ceteris paribus.7 The familiar law of gravity,

is not universally true, for other forces are in play. The force between charged bodies, for example, is a resultant of electrical and gravitational forces. Nevertheless, we are not inclined to jettison the law of gravity. The complication that charge introduces just shows that the law obtains only ceteris paribus, and when bodies are charged, ceteris are not paribus. This is not news. ‘Ceteris paribus’ is Latin for ‘other things being equal’, but it is not obvious what makes for equality in a case like this. Strevens (2012) maintains that where a ceteris paribus claim is correct, its divergences from truth are not difference makers. This is plausible, but uncongenial to veritism. Sklar (1999, 702) glosses ‘ceteris paribus’ as ‘other things being normal’, where ‘normal’ seems to cash out as ‘typical’ or ‘usual’. Then a ‘ceteris paribus law’ states what usually happens. In that case, to construe the law of gravity as a ceteris paribus law is to contend that although there are exceptions, bodies usually attract each other in direct proportion to the product of their masses and in inverse proportion to the square of the distance between them. Again, veritism could handle this.

But Sklar’s construal does not always work. Some laws do not even usually hold. The law of gravity is one, since in addition to gravity, other forces, such as charge, always affect falling bodies. Snell’s law, n1sini = n2sinr, which expresses the relation between the angle of incidence and the angle of refraction of a light ray passing from one medium to another, is a more vivid case.8 As standardly stated, the law is perfectly general, ranging over every case of refraction. It is not true of every case, though; it obtains only where both media are optically isotropic. The law then is a ceteris paribus law. But it is not even usually true, since most media are optically anisotropic (Cartwright, 1983, 46–47). One might wonder why physicists don’t simply restrict the scope of the law: ‘For any two optically isotropic media, n1sini = n2sinr’. The reason is Gricean: expressly restricting the scope of the law implicates that it affords no insight into cases where the restriction does not obtain (Grice, 1989). Snell’s law is more helpful. Even though the law is usually false, it is often not far from the truth. Most media are anisotropic, but many of them—and many of the ones physicists are especially interested in—are nearly isotropic. The law supplies good approximations for nearly isotropic cases. So although explanations and calculations that rely on Snell’s law do not yield truths, they are often not off by much. The cognitive utility of the law involves two factors. One is that the law is approximately true for nearly isotropic media; the other is that those are the media of interest. The acceptability of the law turns, evidently, not on its being true, or being usually true, or even being usually approximately true. It is approximately true in the cases that physicists care about.

The law’s generality is valuable for another reason as well. Sometimes it is useful to first represent a light ray as conforming to Snell’s law, and later introduce ‘corrections’ to accommodate anisotropic media. If we were interested only in the path of a particular light ray, such a circuitous approach would be unattractive. But if we are interested in optical refraction in general, it might make sense to start with a prototypical case, and then show how anisotropy perturbs. By portraying anisotropic cases as perturbations, we point up affinities that direct comparisons would not reveal. The issue, then, is what sort of understanding we want. Showing how a variety of cases diverge from the prototypical case affords valuable insights into the phenomenon we are interested in. And what makes the case prototypical is not that it usually obtains, but that it cleanly exemplifies the features we deem important.

Stylized facts are close kin of ceteris paribus claims. They are “broad generalizations, true in essence, though perhaps not in detail” (Bannock, Baxter, & Davis, 1998, 396–397). They play a major role in economics, constituting explananda that economic models are required to explain. Models of economic growth, for example, are supposed to explain the (stylized) fact that the profit rate is constant.9 The unvarnished fact, of course, is that profit rates are not constant. All sorts of noneconomic factors—such as war, pestilence, drought, and political chicanery—interfere. Manifestly, stylized facts are not (what philosophers would call) facts, for the simple reason that they do not obtain. It might seem, then, that economics takes itself to be required to explain why known falsehoods are true. (Voodoo economics, indeed!) This cannot be correct. Rather, economics is committed to the view that the claims it recognizes as stylized facts are in the right neighborhood, and that their being in the right neighborhood is something economic models need to account for. A critical question is what being in the right neighborhood amounts to. The models may show them to be good approximations in all cases, or where deviations from the economically ideal are slight, or where economic factors dominate noneconomic ones. Or the models might afford some other account of their often being nearly right. The models may differ over what is actually true, or as to where, to what degree, and why the stylized facts are as good as they are. But to fail to acknowledge the stylized facts would be to lose valuable economic information (for example, the fact that if we control for the effects of noneconomic interference such as wars, epidemics, and the president for life absconding with the national treasury, the profit rate is constant). Stylized facts figure in other social sciences as well. I suspect that under a less alarming description, they occur in the natural sciences too. The standard characterization of the pendulum, for example, strikes me as a stylized fact of physics. The motion of the pendulum that physics is supposed to explain is a motion that no actual pendulum exhibits. What such cases point to is this: The fact that a strictly false description is in the right neighborhood is sometimes integral to our understanding of a domain.

Idealizations: An ideal pendulum—the one discussed in physics books, not the one in manuals for clockmakers—is a rigid body consisting of a small mass oscillating through a small angle at the end of a string. It provides a model for simple harmonic motion. The idealization neglects friction and gravity, and it treats the mass of the string as 0. Explanations that represent the pendulum as a simple harmonic oscillator would be epistemically unacceptable if abject fidelity to truth were required. Since every swinging bob is subject to friction and gravity, and every string has some mass, the assumptions built into the model are false. If veritism is correct, its falsity makes it epistemically unacceptable. But scientists find it unexceptionable.

A fortiori arguments from limiting cases: Some accounts focus on a single, carefully chosen case and argue that what holds in that case holds in general. If so, it does no harm to represent the phenomena as having the features that characterize the exemplary case. Astronomy sometimes represents planets as point masses. Manifestly, they are not. But because the distance between planets is vastly greater than their size, their spatial dimensions can safely be neglected. Given the size and distribution of planets in the solar system, what holds for properly characterized point masses also holds for the planets. Another familiar example comes from Rawls (1971). A Theory of Justice represents people in the original position as mutually disinterested. Rawls is under no illusion that this representation is accurate. He recognizes that people are bound to one another by ties of affection of varying degrees of strength, length, and resiliency. But, he believes, if political agents have reason to cooperate even under conditions of mutual disinterest, they will have all the more reason to cooperate when ties of affection are present. If what holds for the one case holds for the others, then it does no harm to represent people as mutually disinterested. That people are mutually disinterested is far from the truth. Conceivably, every person cares about the fates of some other people. But if Rawls is right, the characterization’s being far from the truth does not impede its function in his argument.

The foregoing examples show that in some cognitive contexts we accept claims that we do not consider true. But we do not indiscriminately accept falsehoods either. The question then is, what makes a claim acceptable? Evidently, to accept a claim is not to take it to be true, but to take it that the claim’s divergence from truth, if any, is negligible. As Strevens (2008) puts it, the divergence from truth is not a difference maker. The divergence need not be small, but whatever its magnitude, it can be safely neglected. We accept a contention, I suggest, when we consider it true enough. The success of our cognitive endeavors indicates that we are often right to do so. If so, a contention is acceptable when its divergence from truth is negligible. In that case it is true enough.

As we have seen, contentions that are true enough diverge from truth in different ways. Some diverge in irrelevant respects; others, in relevant respects, but only a little. Yet others diverge (maybe a lot), but only rarely. Some diverge in cases their users do not care about; others, at a finer grain than their users care about. Some diverge radically, but in ways that are informative.

How might the veritist handle such divergences? One possibility is simply to stick to his guns. He might insist that only truths are epistemically acceptable. So if a scientific account ineliminably deploys models or idealizations that are not true, that account is unacceptable. If he is feeling charitable, the veritist might grant that such devices could play a heuristic role in the presentation or application of the theory. But he would insist that for the account to be epistemically acceptable, they must be excisable with no loss of cognitive content or epistemic justification. Such a position is likely to implausibly discredit much of our best science.10

How much is not clear. As we have seen, veritism can apparently accommodate some of the representations I have labeled felicitous falsehoods by construing them as approximations. It might, for example, accommodate Snell’s law, by restricting the domain to nearly isotropic media, and endorsing not

(1) n1sini = n2sinr

but

(2) approximately n1sini = n2sinr.

One difficulty with this approach is that scientists seem to use (1) rather than (2) in their reasoning. Perhaps the veritist can insist that the ‘approximately’ operator, although tacit, is always operative.

But not all felicitous falsehoods are even approximately true. Rawls’s representation of deliberators in the original position as mutually indifferent is far from the truth. So is the Hardy—Weinberg model, which represents the redistribution of alleles in the absence of evolutionary pressures. It tracks alleles in an infinite population of organisms that mate randomly and are not subject to mutation or migration. That the population is infinite counteracts the effects of genetic drift; that mating is random ensures that neither physical proximity nor genes that give rise to attractive phenotypes have a preferential advantage; that neither mutation nor migration takes place ensures that no novelties are introduced into the gene pool. The model is no approximation. Populations are not nearly infinite (whatever that might mean). Mating is not nearly random. However indiscriminate actual mating behavior is, physical proximity is required. In the long run, mating only with nearby partners promotes genetic drift. Natural selection and genetic drift are ubiquitous. Migration is widespread. Mutation and random fluctuations are, in real life, unavoidable. Still, to understand the effects of evolution, it is useful to consider what would happen in its absence. By devising and deploying an epistemically felicitous falsehood, biologists find out. Veritists evidently have to simply deny that accounts that ineliminably deploy devices like the Hardy—Weinberg model or the mutually indifferent deliberators behind the veil of ignorance are epistemically acceptable.

Some approximations are accepted simply because they are the best we can currently do. They are temporary expedients, which we hope and perhaps expect to eventually replace with truths. Such approximations can be construed, in Sellars’s (1968) terms, as promissory notes that remain to be discharged. The closer we get to the truth, the more of the debt is paid. They are, and are known to be, unsatisfactory. But they can be successively improved upon to get them closer to the truth.

Not all approximations have this character. Some are preferable to the truths they approximate. It is possible to derive a second-order partial differential equation that exactly describes fluid flow in a boundary layer. Such an equation describes, for example, how air flows directly over an airplane wing. The equation, being nonlinear, does not admit of an analytic solution. We can formulate the equation, but no one knows how to solve it. This is highly inconvenient. To incorporate the truth into the theory would bring a line of inquiry to a halt, saying in effect: ‘Here’s the equation; it is impossible to solve’. Fluid dynamicists prefer a first-order partial differential equation that approximates the truth, but admits of an analytical solution (Morrison, 1999, 56–60). The solvable equation advances understanding by providing a close enough approximation yielding numerical values that can serve as evidence for or constraints on future inquiry. The approximation then is more fruitful than the truth. There is no hope that future inquiry will remedy the situation if, as may be the case, the second-order equation cannot be solved numerically, while the first-order equation can.11 That reality forces such a choice upon us may be disappointing, but under the circumstances it does not seem intellectually disreputable to accept and prefer the tractable first-order equation. A veritist might argue that acceptance of the first-order approximation is only practical. It is preferable merely because it is more useful. This may be so, but the practice is a cognitive one. Its goal is to understand turbulent flow. In cases like this, the practical and the theoretical inextricably intertwine. The practical value of the approximation is that it advances understanding of a domain. A felicitous falsehood thus is not always accepted only in default of the truth. Nor is its acceptance always second best. It may make cognitive contributions that the unvarnished truth cannot match. These contributions seem out of veritism’s reach.

The veritist’s final alternative is to say that the use of epistemic success terms like ‘knowledge’ and ‘understanding’ in cases that involve felicitous falsehoods is a courtesy usage. Just as we might say, perhaps a little condescendingly, that a young child has some understanding of photosynthesis if she thinks that sunlight is the flower’s food, the veritist might say, a little condescendingly, that Kepler had an understanding of planetary motion, even though his contention that the Earth’s orbit is elliptical is strictly false. Similarly, the veritist might say that a currently promising theory that has its share of successes but some outstanding anomalies constitutes an understanding of its subject matter. In so saying, he is in effect taking out a lien on the future. He credits the current theory because he expects future science to correct its errors and fill its gaps. Arguably, he could say the same thing about a theory that makes currently ineliminable use of felicitous falsehoods. He would then be betting that science will eventually discover the resources to eliminate them without replacing them with other felicitous falsehoods. Fluid dynamics, for example, might find a way to either solve the second-order differential equation that currently cannot be solved, or discover a way to exactly characterize and calculate turbulent flow with a solvable equation that states the exact truth. The difficulty with this stance is that although scientists expect that current models and idealizations will be refined with the advancement of inquiry in their field, they do not expect that science will outgrow the use of such devices. Rather than being seen as temporary crutches, modeling and idealizing are considered valuable ways to embody scientific understanding. So even if the Sellarsian lien on the future is a reasonable perspective to adopt about flawed but promising factual claims, it does not seem a plausible way to understand the epistemic utility of models and idealizations. If contemporary science is our guide, they are here to stay.

Current science is riddled with epistemically felicitous falsehoods. Current scientists are disinclined to repudiate them. This leads me to doubt that they will disappear with the advancement of inquiry. The veritist disagrees. He thinks such devices will ultimately be eliminated or consigned to merely heuristic uses. Crystal balls are notoriously cloudy, so prognosticating about the future of science is a risky business. Instead, in what follows I will develop an epistemological position that shows how felicitous falsehoods function in understanding, what they contribute, and why they are epistemically valuable. What follows will not show that such devices are ineliminable. But it will suggest that their elimination is neither necessary nor obviously desirable.

This chapter has raised an important difficulty for epistemology and pointed toward a resolution. That resolution requires holism, nonfactivism, and a reconception of the basis of epistemic normativity. In the next several chapters I will show how to satisfy all of these requirements. Only then will we be in a position to appreciate the way they equip us to account for the epistemic functions of felicitous falsehoods.

Although I have focused on examples drawn from natural science, I do not contend that all understanding reduces to scientific understanding, or that the use of epistemically felicitous falsehoods is peculiar to scientific understanding. They are, for example, also found in philosophy, history, and the social sciences. As will emerge, I believe that science is epistemically much closer to the arts than is standardly believed. My point in initially focusing on natural science is strategic. Because science is manifestly epistemically estimable, and is self-conscious about its methods and standards, it is often a useful place to focus. The requirement that epistemology accommodate science is nonnegotiable. If science incorporates felicitous falsehoods into its accounts, epistemology needs to explain what they contribute. Nevertheless, I will begin by considering understanding in general, temporarily leaving issues pertaining to felicitous falsehoods in abeyance.

Notes

1. Although I harbor Quinean qualms about propositions, I set them aside here to characterize mainstream epistemology in its own terms.

2. An ‘account’ is what in Considered Judgment I called a ‘system of thought’. I use the bland term ‘account’ to avoid getting involved in disputes about the relation between theories, evidence, and models.

3. I do not have strong intuitions about this case, but I do not think it is clearly wrong to say that the cat has such a belief.

4. As we will see, the issue is not so straightforward as Williams thinks.

5. I will argue later that some falsehoods that purport to be true are nonetheless successful because they are felicitous falsehoods. For now, however, the focus is on sentences that manifestly play a non-truth-telling role.

6. I call them falsehoods out of respect for classical bivalence. One might equally argue that they are neither true nor false. All that I require is that that they are epistemically felicitous although not true.

7. Whether so-called ceteris paribus laws are really laws is a subject of controversy. See, for example, Erkenntnis 57 (2002), for a range of papers on the issue. Although for brevity I speak of them as laws, for my purposes, nothing hangs on whether the generalizations in questions really are laws, at least insofar as this is an ontological question. I am interested in the role such generalizations play in ongoing science. Whether or not they can (in some sense of ‘can’) be replaced by generalizations where all the caveats and restrictions are spelled out, in practice scientists typically make no effort to do so. Nor, often, do they know (or care) how to do so.

8. i and r are the angles made by the incident beam to the normal and n1 and n2 are the refractive indices of the two media.

9. “The profit rate is the level of profits in the economy relative to the value of capital stock” (Bannock, Baxter, & Davis, 1998, 397).

10. The veritist might attempt to soften the blow by arguing that we should be expressivists about science. But it is implausible in the extreme to maintain that natural science is just an expression of our attitudes rather than a discipline whose success depends on the way things actually are.

11. Conceivably, of course, the equations in question will be superseded by some other understanding of the subject, but the fact that the equation we consider true does not have an analytical solution provides no reason to think so. Nor does it provide reason to think that the considerations that supersede it will be mathematically more tractable, much less that in the long run science will be free of all such irksome equations.