9 – Tories Play The Generation Game

“The great Tory reform of this century is to enable more and more people to own property.”

Margaret Thatcher1

Whichever way you looked at it, the election had been called for tactical reasons. May claimed it was to strengthen her hand in the Brexit negotiations. Others saw it as a move to secure her leadership against internal enemies. Some Tories viewed it as a chance to keep Labour from power for a generation. One likely factor was that, without her own election mandate, she would continue to be a prisoner of the 2015 manifesto of her predecessor – as had been sharply demonstrated by the outcry that forced Phillip Hammond to back down after trying to increase National Insurance contributions for the self-employed in the March budget.2 None of these motives went much beyond political expediency. Which is why, on Thursday, May 18, there was no reason to expect the Tory manifesto to contain a compelling big idea – and we would not be disappointed.

On the morning of its launch, two days after ours, it was encouraging to find the media talking about a Corbyn ‘bounce.’ In political parlance, it seems, there are bounces and there are surges, and sometimes it’s very confusing. To my mind, a bounce is a pick-up in support after a specific event, whereas a surge is more sustained and substantial. A bounce, being a lesser thing, is not always easy to detect.

When going back over events for this book, I found the term ‘Corbyn bounce’ had been mentioned earlier than I can remember seeing it at the time. Credit must go to polling expert Matt Singh, who wrote a piece for the Financial Times website on Tuesday, May 16, the day of Labour’s manifesto launch, saying the polls over the four weeks since the calling of the election showed Labour’s share of the vote increasing at a faster pace than the Tories.3 You could say four weeks makes it more of a slow surge than a bounce, but why argue with a positive? It roughly tallied with our assessment at the time that we had gained ground in two, dare I say it, waves: one in the first ten days of the campaign, the other in the period between the leak of the Labour manifesto (May 10) and its official launch (May 16).

By the morning of the launch of the Tory manifesto on May 18,4 evidence of our progress was growing. Polls published that day by the Times (YouGov) and Evening Standard (Ipsos Mori) found Labour’s support had increased by two and eight points respectively to 32 and 34 per cent.5 There was still a double-digit gap between us and the Tories, but social media was buzzing with talk of us bouncing. As the mainstream media gathered in Halifax for May’s first foray into actually revealing some policies, even the commentariat was writing pieces mentioning it. What none of us expected, at that point, was how the Tory manifesto would help put even more spring into our bounce.

It’s not true to say that the cynical Tory manifesto and May’s poor performance gifted us the campaign – as the polls showed, we were already gaining ground by our own efforts – but there is no denying it contributed. The word ‘cynical’ is accurate because the manifesto was so blatant in its betrayal of older voters, suggesting the Tories believed their support was guaranteed whatever nasty medicine they dished out. (They had, after all, retained a big lead among the over 55s, despite shabbily betraying women born in the 1950s on the raising of the state pension age a few years earlier.6)

At the launch of the manifesto, May borrowed much of our language, as she had previously. She spoke of “making Britain a country that works not for the privileged few but for everyone,” and of the Tories being a party that would put government “squarely at the service of working people.” Using a rather feeble play on the words of John F Kennedy, she said the Tories would build “a country that asks not where you have come from but where you are going to.”7

It was spun as a break with Thatcherism, but the only sense in which that was true was in her betrayal of people who had literally bought into the Thatcherite dream of being a property owner and were now being told it was contingent on them not falling ill in later life. The headline-catching policy in the manifesto, which came almost immediately to be called ‘the dementia tax’, was the inclusion of the value of someone’s home, rather than just their savings, when calculating whether or not they would have to pay for their own social care.

Home ownership increased by a third in the Thatcher years, creating 4 million more owner-occupied households. About half of the increase was council houses and flats sold off at discounts of up to 50 per cent. Now, in this great act of treachery, the Tories were looking to get the money back to pay for social care.

At Southside, John McDonnell, Ian Lavery and several of us from the LOTO and shadow treasury teams had gathered in a committee room to watch May’s speech and discuss how we should react to the manifesto. Deciding the main issues we would highlight was one of the easier decisions of the campaign. As well as forcing older people to pay for care if they need it with their homes, the Tories were going to make them go through a means test before getting Winter Fuel Payments and scrap the triple lock that guarantees pensions will rise by 2.5 per cent regardless of what happens to prices and earnings. They were leaving the Osborne tax giveaways to big business and the wealthy intact, including cutting corporation tax to 17 per cent by 2020. However, for everyone else, there could be higher tax bills: the 2015 manifesto promise not to increase income tax and National Insurance contributions was dropped.8

We lost no time in sending a statement out to the media saying that “behind the rhetoric, this is a manifesto that offers the majority of working people and pensioners insecurity with a huge question mark over their living standards.” We did not need to do much more at that point, so huge was the outcry on social care.

Trouble was brewing for the Tories even before May was on her feet in Halifax. It is customary for the media to be fed some of the key points from a manifesto the day before its launch (the idea being to get coverage in two 24-hour news cycles). In this case, the tactic had prompted the Radio 4’s Today programme to interview Andrew Dilnot, who had chaired a Commission on Funding of Care and Support in 2011.9 Having clearly been given advance warning of what was in the manifesto, he said:

“People are faced with a position of no control; there’s nothing that you can do to protect yourself against care costs. You can’t insure it because the private sector won’t insure it, and by refusing to implement a cap the Conservatives are now saying that they’re not going to provide social insurance for it, so people will be left helpless knowing that what will happen, if they’re unlucky enough to suffer the need for care costs, is they’ll be entirely on their own until they’re down to the last £100,000 of all of their wealth, including their house.”

This, he pointed out, was “a classic case of market failure,” yet May had promised in her speech to the Tory conference eight months earlier a new approach of the state providing what markets could not.

On LBC Radio, a woman caller told presenter Shelagh Fogarty:

“She’s definitely lost (my vote) with this one. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing this morning. It’s a pure evil. It is definitely a death tax, another form of inheritance tax and I don’t know what they’re thinking….It’s the nasty party back. This is a tax on people who have bothered to buy their own home and to invest a little bit of money into somewhere to live.”10

Later, another caller into Iain Dale’s programme, said: “She [May] thought she was going to have such a landslide, that every one of us mugs that have voted Conservative all our lives would give her it. My husband can’t bring himself to vote for Labour, but I have already sealed my postal vote for the Labour party…I will burn my house down before I give Theresa May a penny of it.”11

To add to May’s woes, a Tory think tank, the Bow Group, also came out strongly against the manifesto proposal, calling it “a tax on death and on inheritance.” Their chairperson Ben Harris-Quinney, said:

“It will mean that, in the end, the government will have taken the lion’s share of a lifetime earnings in taxes. If enacted, it is likely to represent the biggest stealth tax in history, and when people understand that they will be leaving most of their estate to the government, rather than their families, the Conservative party will experience a dramatic loss of support.”12

That afternoon, we worked on the different elements of our response and finalised arrangements for our own press conference the next morning. My focus was on the key messages and graphics for the event. After kicking a few ideas around, we settled on “Tory triple whammy for pensioners” as a strapline, and I asked Krow Communications to come up with something that would work on social media and at the press conference. The result was an image with the strapline above three giant red boxing gloves saying on each in turn: “No triple lock”, “No winter fuel allowance,” and “Pay for care with your home.” It was simple and did the job.

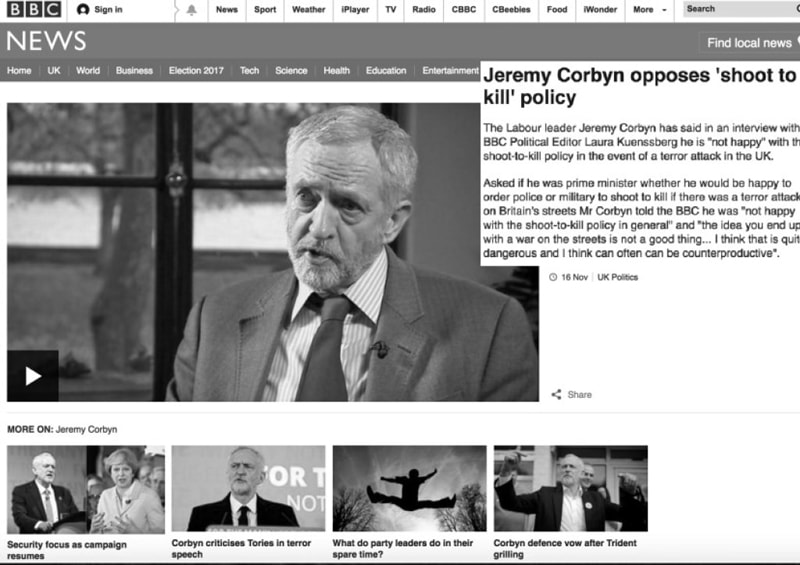

At the same time, we decided to dip into our digital budget to buy ‘dementia tax’ on Google AdWords. The way this works is that an advertiser can bid for a term so that their advert appears next to the Google search results when people look for that subject. We wanted anyone searching for information on the Tory proposal to see, at the top of the page, a link that would take them through to a Q&A the campaign had produced exposing how it would hit people. Google AdWords is usually seen by political campaigners as a way of getting information in front of ‘opinion-formers,’ such as journalists or policy wonks who are interested in a subject and can influence other people. In this case, I felt a large number of older voters alarmed about the dementia tax would also be searching for it. Google AdWords is not as targeted as Promote, but it is an effective campaign tool when a topic is hot and you need to influence the debate as quickly as possible. We would use it again later in the campaign for ‘Brexit’ and ‘Shoot-to-kill.’

As we prepared for the next day and the weekend, one of the worries I had was the way the Tories were playing up a divisive ‘inter-generational inequality’ argument to justify the dementia tax. They had devoted a whole section of the manifesto – one of only five – to what they were calling “A Restored Contract Between The Generations.” In the introduction, it said “the solidarity that binds generations” was “under strain” and that maintaining it would at times “require great generosity from one group to another – of younger working people to pay for the dignified old age of retired people, and of older people balancing what they receive with the needs of the younger generation.” Giving older people “the dignity we owe them” and younger people “the opportunities they deserve” would, the manifesto said, mean facing “difficult decisions.” Behind the euphemisms, this was a slippery exploitation of the word inequality to play one part of ‘the many’ off against another – a classic case of divide and rule, allowing the rich to continue to enjoy their tax breaks and hide most of their assets in tax havens.

The Sunday Times Rich List, published only two weeks earlier, showed that the real issue is the vast and accelerating disparity in wealth between a tiny minority and everyone else, whatever their age. The combined wealth of the 1,000 people on the 2017 list was £658 billion, a 14 per cent increase on the previous year. During the previous seven years of austerity, the wealth of those on the Rich List had almost doubled. Some older working people living in London may, during that period, have got lucky with the value of their own home, but that pales into insignificance compared to the wealth accumulated by the likes of Sir James Dyson (#14, £7.8 billion) or the Duke of Westminster (#9, £9.5 billion).13

Besides, as Anna Dixon of the Centre for Ageing Better had put it a few months earlier, the idea of inter-generational inequality “also ignores the way wealth is passed down between generations within families.” Working class families are much better at solidarity between the generations than the Tories will ever be with the public finances. Some 75 per cent of people over the age of 65 own their own home, and most see it as an asset that will be passed on to their children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews.14

Late that Thursday evening, I sent an e-mail to Seumas and Andrew Murray saying I thought a speech Jeremy was due to make in Birmingham that Saturday should be on the theme of “uniting generations” and “standing together to build a fairer Britain.” It should spell out that the Tories have “made it impossible for young people to buy a home” and are now “making their parents use their home to pay for their care.” We had already decided to make pensioners the theme of the weekend, followed on Monday by the announcement of our policy on tuition fees – the speech would link the two. Seumas and Andrew agreed and worked the idea into their draft for Jeremy.

The following morning’s strategy meeting was one of the most upbeat of the campaign. The general feeling was that the mood was moving our way, but Seumas was concerned that we had not really landed a punch. In some ways, we didn’t need to – disgruntled Tory voters were doing it for us – but there was a danger of our voice getting lost in the furore. We agreed that John McDonnell should make a specific call at the press conference for the Tories to immediately withdraw their plan to means test Winter Fuel Payments, and I was despatched to the venue to brief him. When I got to the venue near The Embankment, John was in a side room raring to go and took no persuading that we needed a strong line for the lunchtime bulletins. The press conference was well attended and largely achieved what we wanted: a platform for our response to the Tories and something visual for the mainstream media. But it did also confirm the correctness of our decision not to have too many press conferences because some of the journalists could not resist the opportunity to try to catch John out on things he had said decades earlier on Northern Ireland.

Leaving the venue, it took my eyes a while to adjust to the brightness of a sunny late spring day, and I realised just how little time I had spent outside in daylight since the election was called. I have a minor hereditary heart condition which causes chest pains when my weight goes above a certain level, and I had been having trouble because of the unhealthy diet and lack of exercise that went with the campaign. The previous day Karie had taken me in hand. When she discovered I had left my tablets in Cardiff, she insisted on dragging me to the nearest pharmacy where she impressively used her know-how as a former health visitor to blag a small supply that would get me to the weekend.15 That Friday morning, I decided to walk the couple of miles to Southside and then go back to Cardiff earlier than usual on a mid-afternoon train. We still had nearly three weeks of campaigning to go, and I knew I needed to pace myself.

That Saturday, I watched the live feed of Jeremy’s rally in Birmingham online. The text of the speech sent out in advance to the media was very good, but Jeremy decided to add to it – he wanted to have what he calls an “off-piste” moment. Speaking at the International Convention Centre to an enthusiastic audience of supporters and their friends, he was bound to get a good reception. But the passage calling for inter-generational unity – both the original and Jeremy’s additions – was interrupted six times by applause, sometimes mid-sentence. He was clearly echoing everyone’s anger only two days after May had played the divisive ‘inter-generational inequality’ card.

After some introductory words, he came to the unity passage and delivered the opening part mostly as it was drafted:

“The Tory manifesto must be the most divisive for many elections. They are now pitching young against old. Their manifesto is typical of what a very well-known person once called a nasty party, as they attempt to set one generation against another. For pensioners they offer a triple whammy of misery: Ending the ‘triple lock’ which protects pensioner incomes, means-testing the Winter Fuel Allowance and slapping a ‘compassion tax’ on those who need social care by making them pay for it using their homes. Some claim that cutting support for the elderly is necessary to give more help to the young. But young people are being offered no hope by the Tories either – loaded with tuition fee debts, with next to no chance of a home of their own or a stable, secure job. We stand for unity across all ages and all regions in our country.

“It is simply wrong to claim that young people can only be given a fair deal at the expense of the old, or vice versa. We in this hall and in every street across the country know that the reality is we all depend on each other. That is why we are calling on the Tories to drop their anti-pensioner package immediately – older people should not be turned into a political football at this election at the behest of the Prime Minister. And we promise that a Labour government will make education free at all levels and build the homes young families need, offering the security of a home for life. It’s something many people dream about, we want to make it a reality. Because our manifesto, this party, stands for the many against government by, of and for the few.

“We say that if we all stand together we can build a fairer Britain. There is no trade-off between young and old – and there should be no trade-off at all. Society should not be setting the future of our young against the security of our old.”

And then Jeremy came to a passage he had added entirely:

“I find it deeply offensive that we should get into this kind of discussion and debate. Older people who’ve made such a fantastic contribution to our society, and in retirement continue to make that contribution in voluntary activities, in inspiring people, in supporting young people. And young people who seek the advice and solace of older people. It’s not a war between generations, it’s a unity of generations to create a better society for all.”

The last sentence brought the house down, showing how strongly people felt about the cynical divisiveness of the Tories. Jeremy going off-piste always worried the speechwriting team, but only because we feared it could create an awkward moment with the autocue or inadvertently introduce a phrase that could be misquoted. We wrote speeches knowing Jeremy’s views and using the phrases he liked. But Jeremy had added a dose of passion. Out on the road, he was closer to the popular mood and becoming more assured as each day passed in responding to it. In this case, it was also personal: nothing angers him more than an attempt to pit people against each other.

Working through the afternoon at home, I followed Jeremy’s journey north to the Wirral on social media. He was due to speak at a rally at West Kirby beach where thousands of people, including my youngest son, Josh, were gathering in a car park to hear him. Watching several video posts, I was taken aback by the size of the crowd on such a rainy and windy afternoon. But I was even more surprised a couple of hours later when I saw photographs on the LOTO WhatsApp group of staff in the stands at Prenton Park, the home ground of Tranmere Rovers. Jeremy was about to go on stage at the Wirral Live festival to speak to the 20,000 or so music fans. The operational note for the weekend had not mentioned the event. It was added at the last minute by Karie, who knew one of the organisers, despite initial objections from the police responsible for Jeremy’s personal protection.

My anxieties, however, were about possible heckling rather than security: people were there for the music, not to hear what they might consider a gate-crashing politician. If going ‘off-piste’ in Birmingham was a risk, this was like Jeremy trying Olympic ski jumping. But it was a triumph: in a short speech Jeremy hit (apologies for the pun) all the right notes. You can’t go wrong talking about working class communities building football clubs and making music on Merseyside. And, as he ended with a rousing “This election is about you and what we can achieve together,” the crowd started singing ‘Ohhhh, Je-re-my Cooorbyn, Ohhhh Je-re-my Coooorbyn’ to the tune of Seven Nation Army. It was an unforgettable moment and – as someone born not far from Prenton Park16 – one of the most emotional of the campaign. Within 24 hours, Jeremy’s own posts about the event had reached more than 8 million people on Facebook and Twitter.

In the papers that Sunday, all the polls showed us increasing our vote share and closing the gap on the Tories. The best and closest from our point of view were those where the fieldwork had been done after the Tory manifesto was published, including YouGov’s poll for the Sunday Times, which had Labour only nine points behind the Tories on 35 per cent, the first poll of the campaign to show a single digit gap. The Andrew Marr Show, which was calling it the Tories’ wobbly weekend, had interviews with both the work and pensions secretary, Damian Green, and John McDonnell on the respective manifestos. Green repeatedly refused to say at what level the means test would be set for Winter Fuel Payments, insisting it would be decided after the election. When Marr questioned him on the dementia tax, Green played the ‘inter-generational fairness’ card and argued it was unfair for people working now to pay taxes to fund care for pensioners. But Marr, with more than a hint at his own experience of how anyone can be struck by poor health at any time, put it to him that pensioners have paid taxes to insure themselves against bad luck:

“It’s very unfair that some people get dementia and some people don’t. Under the original Dilnot system, we pooled the risk in society after a certain threshold and spread out the unfairness. If you are very unlucky and you get a terrible disease that means you are being looked after at home, maybe a stroke where you don’t return to work or whatever it might be, then the rest of society will come in and help you. You don’t have to pay again. Under the new proposals, you are basically on your own for most of it.”17

Green was looking increasingly uncomfortable, and the debate about making pensioners pay with their homes, for care they thought they had paid for with a lifetime of taxes, would run and run on every media channel right through that day and into the next.

However, while the campaign clearly had the Tories on the ropes, someone nominally in our own corner could not restrain themselves from making mischief. The Sunday Times was running a report headlined “Don’t mention Corbyn, aide tells Labour candidates” based on a leaked recording of a conference call briefing I had given the previous Wednesday. The report said that I had been asked by one of the 167 candidates on the call how canvassers should deal with voters who openly criticise Jeremy and quoted me as replying they should “focus…on the manifesto and the policies rather than individuals.” For anyone who has been canvassing and knows how little time there is on the doorstep, my response would have seemed fairly standard. My own experience of canvassing is that you try to shift the conversation away from a point of disagreement, whatever it is, onto something that might be more fruitful. Besides, Jeremy himself would always put the emphasis on policy. It was another non-story, apparently supplied to Tim Shipman from a disappointingly disloyal candidate.18

Meanwhile, in the same newspaper, Seumas’ predecessor as Labour’s director of strategy and communications was giving further grist to the Tory mill by accusing Jeremy of “preparing for nothing more than his annual summer leadership contest.” In a complete travesty of the truth, Tom Baldwin claimed:

“People were initially puzzled about why [Jeremy] was spending so much of this campaign addressing rallies of committed activists in seats unlikely to be on any target list until it was pointed out these were places where lots of the members who elected him to the leadership lived.”19

How Baldwin knew where people who voted for Jeremy lived is intriguing given it was supposed to be a secret ballot. However, the seats Jeremy had visited were easy enough to check. Had he taken the trouble to do so, he would have found – as noted in Chapter 7 – that Jeremy was mainly visiting offensive seats. At this point, of the 48 seats he had been to, only 20 were Labour held. Of the 28 offensive seats, Labour went on to win 13 of them, and several more – such as Dunfermline & West Fife, Telford, Pudsey and Calder Valley – proved very close.

That Sunday afternoon, I returned to Southside to find the LOTO strategy group undistracted by sniping from the side-lines and eager to keep the momentum going. The priority, we agreed, was a major ‘northern push’ with shadow cabinet members mobilised to visit as many target seats as possible. And, in continuing the campaign to win more older voters, our central message would be that a means test for Winter Fuel Payments would be a prelude to an attack on other universal pensioner benefits such as free TV licences and prescription charges.

The deadline for voter registration was 24 hours away and all our teams were gearing up for a big final push, including an e-mailer to our supporter database and social media activity across all the feeds. The huge array of content we had ranged from numerous celebrity endorsements to a snappy 15 second video saying: “Good morning. Things to do today: register to vote, hit RT to remind your friends, put your feet up.” To give the campaign a final boost, we released that evening the details of our pledge to abolish tuition fees with immediate effect, giving 18-year-olds sitting their A levels that summer “yet another reason to register to vote” before the deadline of midnight on May 22.

My first message on the morning of voter registration deadline day was a welcome one from an old Labour friend in Sheffield, Debbie Woodhouse, another member of my informal focus group. She had not voted for Jeremy to be leader but was now pleasantly surprised by the way the campaign was going. “So many people I know are starting to think they may vote Labour, and I think this is because the message is getting out there about who he is and what he stands for,” she said. She thought we were offering “a clear choice for the first time for decades for a new type of politics” and felt it was “a historic moment.”

Within a few hours, Debbie’s optimism was further vindicated by a shambolic U-turn from Theresa May on the dementia tax. In a speech that sounded panicky and Trump-like, she accused Jeremy of ‘“fake claims, fear and scaremongering” before surprising everyone by saying there would be “an absolute limit on the amount people have to pay for their care costs.”20

Only a few days earlier her own health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, had argued a cap would be “unfair” because someone with a house worth “a million pounds, 2 million pounds” should not have their care costs limited and therefore “born by taxpayers, younger families who are perhaps struggling themselves to make ends meet.”21

Hunt’s professed concern about struggling young families was hypocritical and typically divisive, but his point on the cap does illustrate how any form of self-funding of care is hard to reconcile with being fiscally progressive (that is, raising money in proportion to someone’s wealth or income). Among home-owning pensioners, generally speaking, the more your home is worth, the more you benefit from a cap.

Labour’s manifesto promised to build a National Care Service with an additional £3 billion of funding every year “to place a maximum limit on lifetime personal contributions to care costs, raise the asset threshold below which people are entitled to state support, and provide free end of life care.” It goes on to say that in the long term we would “seek consensus on a cross-party basis about how (social care) should be funded, with options including wealth taxes, an employer care contribution or a new social care levy.”22 This was far better than the Tory position, but it still contained a concession to the concept of what is – however you look at it – means testing. The danger is that once you move from a social insurance to a partially self-funding model you are on a slippery slope: it becomes only a matter of where you draw the lines.

In my view, someone who has dementia or a severe stroke and needs ongoing care should be treated no differently from someone who has cancer, or any other condition that may involve costly treatment over a long period. Socialists, quite rightly, defend the principle of universality and argue that the question of inequality in assets and income should be addressed through a progressive tax system. The manifesto mentioned a wealth tax, but it also accepted the idea of some level of personal contribution. It was an understandable compromise in the time available to finalise our platform for the election, but the issue is not going to go away.

Those long-term policy questions, though touched on in our discussions that day, were not the most pressing concern. A crack had appeared in the now shaky Tory edifice, and we needed to shine a light on it. In discussing our immediate reaction to the U-turn, we agreed to focus on how unfair the Tory policy muddle was on the elderly. Not only had May abandoned her manifesto policy after only four days, she had also not said what the limit would be. We rushed a statement out from Andrew Gwynne saying she had thrown her own campaign into chaos and confusion:

“By failing to put a figure for a cap on social care costs, she has only added to the uncertainty for millions of older people and their families. This is weak and unstable leadership. You can’t trust the Tories – if this is how they handle their own manifesto, how will they cope with the Brexit negotiations?”

The Tories were desperate, meanwhile, to deflect attention from their dementia tax disarray. That morning, the Northern Ireland secretary, James Brokenshire, issued a press release “demanding Jeremy Corbyn and his top team come clean about their true attitudes towards IRA terrorism.” The release said:

“In recent days, Corbyn, his closest ally John McDonnell and shadow home secretary Diane Abbott have all been revealed as having extremely worrying views about the campaign of violence carried out by IRA terrorists. On Sunday, Jeremy Corbyn – who could be prime minister in 18 days – failed to condemn IRA bombing FIVE times.”

The Tories attached to their release a transcript of an interview of Jeremy by Sophy Ridge on Sky the previous day. It was not true that Jeremy had failed to condemn the IRA – in fact, at one point he said “of course I condemn it” – but what Ridge was trying to do was get him to single out the IRA exclusively and not at the same time condemn the violence of loyalist paramilitaries, as he always did. The Tories may not have briefed Ridge, but it was certainly a convenient line of questioning that helped them move onto the attack.

Brokenshire’s release challenged Jeremy to answer a series of very specific questions: Does he condemn the IRA’s acts of murder unequivocally? Were the IRA terrorists? Did the deaths of members of the armed forces count as ‘innocent lives’? And does he regard the armed forces and the IRA as ‘equivalent’ participants during the troubles? With media inquiries pouring in, James Schneider worked on Jeremy’s response. The answers were direct (in order): yes; yes, the IRA clearly committed acts of terrorism; yes, all loss of life is tragic; no. These answers were, however, still put in the context of a statement giving Jeremy’s more rounded view:

“I condemn all acts of violence in Northern Ireland from wherever they came. I spent the whole of the 1980s and 1990s representing a constituency with a large number of Irish people in it. We wanted peace, we wanted justice, we wanted a solution. The first ceasefire helped to bring that about and bring about those talks, which were representative of the different sections of opinion in Northern Ireland. And the Labour government in 1997 helped to bring about the Good Friday Agreement (GFA), the basis of which was a recognition of the differing history, cultures and opinions in Northern Ireland. It has stood the test of time and it is still there.

“We have devolved administration in Northern Ireland, and I think we should recognise that that peace was achieved by a lot of bravery, both by people in the unionist community and in the nationalist community. They walked a very difficult extra mile under pressure from communities not to do so, both republicans and unionists walked that extra mile and brought us the GFA. And I think we should use this election to thank those who brought about the GFA, all of them. Those in government at the time and all those who did so much on the ground. Northern Ireland is a very different place. We’re going to be working with the devolved government in Northern Ireland as well as the government in the Republic to ensure that Brexit doesn’t bring about a barbed wire border. We don’t want a hard border.”

The final part of the statement reflected the growing confidence in the campaign that Jeremy could be the next prime minister, and would indeed be working with the Irish government and the devolved government in Northern Ireland on Brexit and other issues. Paradoxically, the Tory attack – by highlighting that Jeremy could be heading for Downing Street – may have helped our momentum. The Tories were beginning to look like a party running scared, and Jeremy was – with every speech and in brushing off the attacks – looking ever more confident and composed.

That Monday evening, news came through of a remarkable YouGov poll of Welsh voting intentions: Labour was up nine points to 44 per cent and the Tories were down seven points to 34 per cent. The end was far from nigh for Labour in Wales. Maybe I would be able to show my face in Cardiff, after all.

Jeremy Corbyn leaves his house the day after denying the Tories a majority.

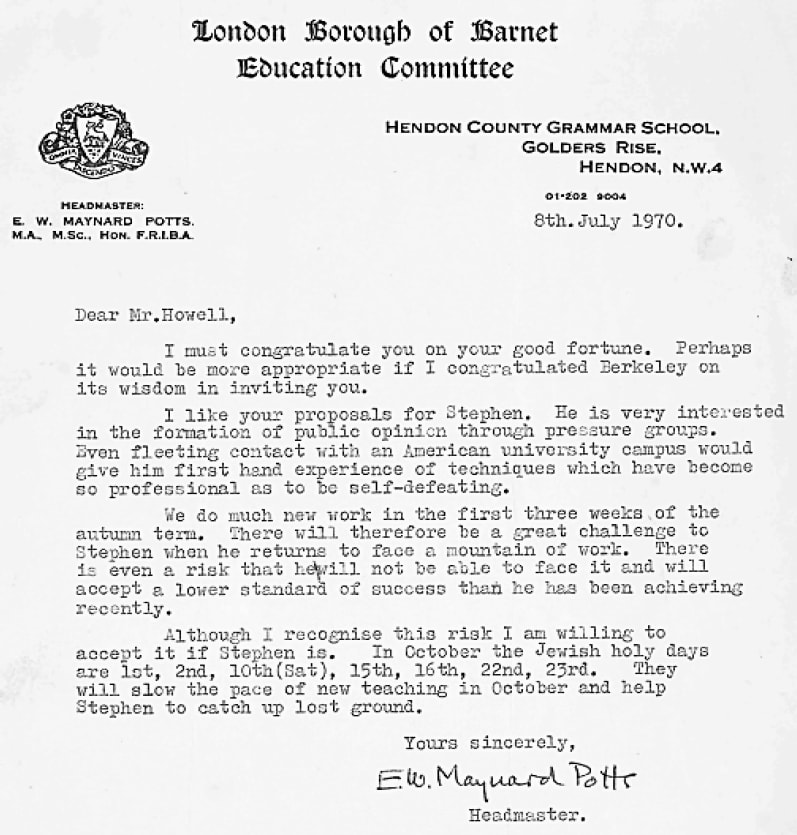

My headteacher says I’m “very interested in the formation of public opinion through pressure groups.” But there’s a sting in the tail.

Peter Mandelson (bottom left) and me (top right) in a Hendon County sixth form photograph (1971).

Tony Benn delivers the George Caborn Memorial Lecture in 1985. I appear to be still writing my notes for the appeal. George was one of South Yorkshire’s best-known union leaders. His son, Richard, was MP for Sheffield Central and later minister for sport.

Bernie Sanders speaks to a 13,000-strong crowd at the Los Angeles Coliseum on 4 June 2016, three days before the California Democratic primary.

Actor and activist Susan Sarandon arrives to introduce Bernie Sanders.

The area set aside for media and campaign guests.

Feel The Bern campaign T-shirts.

I’m official – showing off my parliamentary pass after collecting it.

Freshwater colleagues wish me luck in my indefinite leave of absence.

Canvassing for the local elections in Butetown ward, Cardiff with Derek Walker, Harry Edgeworth, Saeed Ebrahim and Lyn Eynon. Saeed won handsomely.

My photo of the scene on Westminster Bridge, just after a lone terrorist attacker had driven into pedestrians on 22 March 2017 (see Chapter 3).

Jeremy gives everyone a pep talk at the end of the five-hour ‘lock down’ following the Westminster attack.

Barry Gardiner and David Prescott watch the TV in the main LOTO office as Theresa May announces a snap election on 18 April, 2017.

My son, Gareth, and my granddaughter, Ilana, read a letter from Jeremy explaining why I would not be able to get to California for her fifth birthday.

LOTO team members gather for a quick snap with Jeremy just before moving to Southside for the campaign. Left to right, back row: Thomas Gardiner, James Meadway, Chris Flattery, Angie Williams, Ayse Veli, Rich Simcox; front row: Mark Simpson, Seumas Milne, Jeremy and Laura, Sian Jones, Sophie Nazemi and Liz Marshall.

Ken Loach briefs Jeremy ahead of filming an interview with Labour supporters for one of the party political broadcasts.

Jeremy and Laura relax ahead of filming with Ken Loach.

Chaotic scenes in Cardiff as Jeremy speaks to an unexpectedly large crowd on 28 April 2017, with Wales First Minister Carwyn Jones (bottom right).

My daughter, Cerys, canvasses in the local elections with my grandson, Gwilym, then just three months old.

Jeremy loves travelling by train, with his notebook always handy.

Jeremy chats to a supporter in Warrington on 29 April, one of hundreds of conversations he had during the campaign.

Tories wrap the Mansfield Chad on 3 May with an advert that plays the Brexit card but doesn’t mention the party.

Theresa May looks miserable as Jeremy pops up with a question during her ‘Facebook Live’ on 15 May, 2017.

The Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph rubbish our leaked manifesto on 11 May, 2017 with almost identical headlines.

Ready to react to the Tory manifesto on 18 May 2017. Left to right: Rory MacQueen (Shadow Treasury team), John McDonnell, Ian Lavery, Suha Abdul (STT), James Mills (STT), Seumas Milne, Madeleine Williams (STT) and Karie Murphy.

The Daily Mirror leads with the Tory attack on Winter Fuel Payments the day after their manifesto launch.

Feeling very optimistic as Jeremy Hunt struggles to explain the Tory manifesto.

Beccy Long-Bailey delivers our verdict on the Tory manifesto’s ‘Triple Whammy’ at a press conference on 19 May 2017.

The Evening Standard reacts to May’s U-turn on a dementia tax cap on 22 May 2017.

Left: Our final social media reminder about voter registration on deadline day – 22 May 2017.

Above: Andrew Fisher ticks off constituencies visited in the glasshouse used by Jeremy and the LOTO strategy group.

Jeremy speaks to an invited audience and the media as campaigning resumes following the Manchester attack.

An adaption of an old slogan sums up the two aspects of Jeremy’s security stance.

The BBC website page on shoot-to-kill as it was on 4 June 2017 - conflating shoot-to-kill ‘in general’ as a ‘policy’, which is illegal, with the legal use of lethal force to save lives during a terror attack (see Chapter 13).

The Tory ‘dog whistle’ AdVan tours the north-west. Why is Diane on there and not her Tory opposite number, Amber Rudd? (See Chapter 12).

LOTO strategy group members view the final cut of the campaign video. Left to right: Katy Clark, John McDonnell, Andrew Murray, Seb Corbyn, Leah Jennings (adviser to Jon Trickett), Seumas Milne, Jack Bond and Jon Trickett.

The Daily Mail and Sun do their bit for the Tories on the day before voting.

The LOTO communications team ready for the results on election night. Left to right: James Schneider, Ben Sellers, Rich Simcox, Angie Williams, Sophie Nazemi, me, Sian Jones, Joe Ryle, Jack Bond and Georgie Robertson.

Off-duty Labour staff celebrate at Southside as the gains roll in.

Seumas and Karie at home with Jeremy on election night.

Ian Lavery and Jeremy have a quiet moment at a reception for new Labour MPs on June 13.

L’myah Ross Walcott, Karie, Jennifer Larbie and Patsy Cummings enjoy election night.

Jeremy joins LOTO and campaign staff for a team photograph just after the election.

1 Margaret Thatcher, speech to the Conservative party conference, 10.10.1986.

2 In the 2015 general election, the Tory manifesto promised there would be no VAT, NI or income tax rises for the next five years under a Conservative government. It was this pledge Philip Hammond had broken when he announced the increase in NI rates for the self-employed on 8.3.2017.

3 Matt Singh, ‘What is really happening in the run-up to June’s election,’ the Financial Times, 16.5.2017.

4 The Tory manifesto was launched in Halifax on 18.5.2017.

5 UK Polling Report. See also, for example, Sarah Ann Harris, ‘Latest general election polls show Labour bounce as Jeremy Corbyn narrows gap with Tories,’ the Huffington Post, 18.5.2017.

6 The Tory government of John Major first introduced legislation to raise the state pension age for women to 65. In 2011, however, the Coalition government under David Cameron brought the increase forward without warning and also raised the pension age to 66, sparking the Women Against State Pension Inequality (WASPI) campaign.

7 US President Kennedy famously said in his inaugural address: ‘Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country,’ 20.1.1961.

8 Of Cameron’s ‘triple lock’ on taxes, May retained only the commitment not to increase VAT.

9 Sir Andrew Dilnot, an economist and the warden of Nuffield College, Oxford, was appointed by Cameron’s Coalition government to chair the commission. It recommended capping an individual’s contribution to care costs at £35,000.

10 See: ‘I was going to vote Tory until I saw the manifesto - callers tell Shelagh,’ www.lbc.org.uk, 18.5.2017.

11 See: ‘Irate caller threatens to burn house down over Tory manifesto,’ www.lbc.org.uk, 18.5.2017.

12 Bow Group press release, ‘The biggest stealth tax in history,’ 18.5.2017.

13 Rich List 2017, the Sunday Times, 7.5.2017.

14 Anna Dixon, ‘We need to stop our divisive obsession with intergenerational unfairness,’ the Daily Telegraph, 6.11.2017. She is chief executive of the Centre for Ageing Better.

15 Karie was a health visitor in Glasgow before becoming Unison’s full-time head of health in Scotland and then moving to London to work for the union as head of health for the UK.

16 I was born in nearby Wallasey.

17 The Andrew Marr Show, BBC, 21.5.2017.

18 Tim Shipman, ‘Don’t mention Corbyn, aide tells Labour candidates,’ the Sunday Times, 21.5.2017.

19 Tom Baldwin, ‘Win seats, Jeremy, or do an Ed,’ the Sunday Times, 21.5.2017.

20 Laura Hughes, ‘Theresa May announces dementia tax U-turn,’ the Daily Telegraph, 22.5.2017.

21 Kate Proctor, ‘Theresa May faces Tory unrest over unfair social care reforms,’ the Evening Standard, 19.5.2017.

22 Labour party manifesto, ‘For the many, not the few,’ 2017, p71-2.