California Institute of Technology, April 199937

I feel overawed at the idea of coming to Caltech, particularly as I’m a guilty fugitive from science.

I descended into the disreputable morass of the theatre and constantly feel remorse at having lost what I believe to be, and what my teachers thought was, a more serious subject. There are still one or two ageing professors of mine whom I always cross the street to avoid for fear of meeting their disapproval.

I’ll start by talking about a question which I’m often asked: how is it possible for someone who had an interest in the biological sciences, and then in medicine, and then in neurology, to go into the theatre? Aren’t they completely incompatible? Aren’t they incommensurable disciplines? In fact, in some mysterious way there is a curious and almost inevitable connection between the work that I was trying to do in neurology and the work that I continue to try to do in the theatre. It has to do with the fact that my interest in neurology and my interest in the brain was never specifically neurophysiological. I was never a good enough mathematician or a good enough biophysicist to be in traditional, hard, cutting-edge neurophysiology, though at Cambridge I was taught by some of the greatest men in the field: the late Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley and E. D. Adrian. So I was, as it were, brought up in the purple of the subject, but embarrassingly recognized at a very early stage that I really wasn’t up to the maths and physics required to do important neurophysiological research. But in any case I think that my interest in the brain was almost entirely connected with what I would call ‘higher orders’ of human action; I was really interested in what went wrong with the brain and what went wrong with conduct, with movement, with speech and with perception. And I recognized that I could probably make a perfectly interesting career for myself in the qualitative observation of patients’ behaviour, competences and performance as a result of brain damage.

I undertook to take a medical degree, not because I was interested in helping anyone; I didn’t really want to go into medicine to do good. I didn’t want to do harm, but I knew that a medical degree assured you a ringside seat closer to the action than you could have if you were merely qualified as a neurophysiologist. You were allowed to ask ruder questions and poke your hands into ruder parts than you could if you didn’t have a medical degree. I was interested in seeing what happened when the brain was damaged, what it was that people couldn’t do, and I hoped that would give me some sort of insight into what went into being able to do the things that we seem not to have to think about.

One of the extremely striking things about human behaviour is the peculiar transparency, and indeed inaccessibility, of the apparatus which mediates our performances and our competences. If mine were the only brain in the world, and I didn’t have access to other people’s brains – which I could see by opening their skulls – then I wouldn’t know that I had one, nor would I have any information from my competence or from my experience or from my performances or from my sensations. I would not actually be aware of the fact that all of these things were mediated in some way by some material substance or some material apparatus.

In a sense I’m reminded of this rather more acutely by having recently curated an exhibition on reflection at the National Gallery in London.38 I was struck by the fact that the mirror has been so frequently invoked as a metaphor for the mind, for the reason I think that there is nothing to be seen in a mirror except what the mirror reflects – that the mirror only gives you an image of a world elsewhere; it gives you an image of the world of which it is a reflection. And looking into a mirror, try as you can, unless the mirror is flawed or damaged in some way, you are absolutely unaware of the medium which supports the reflection of which you are conscious. The only thing that can be seen in a mirror is what it reflects. You don’t see the mirror itself at all, though of course you get these rather peculiar and paradoxical experiences in which, when you are aware of the fact that it is a mirror – if you have circumstantial evidence to the effect that what you are looking at is not a window, for example, but is in fact a mirror and is reflecting something – in addition to seeing what it reflects, in some mysterious way you are also aware of its objectively non-existent surface.

I was first struck by this about ten years ago when my wife and I were driving back from Switzerland and stopped off for a rest at a lakeside on the Swiss-French border.39 And I immediately noticed the peculiar sheen, a shine on the surface of the lake. I found myself asking my wife what to her was an extremely tedious question, and that was, ‘Why does it look so glassy?’ And she said, ‘Well, because it is glassy.’ And I said, ‘But there’s nothing to be seen on the surface of the lake except a perfect upside-down replica of what’s to be seen on the other side of the lake. If you look very carefully, there is no debris floating on the surface, there is no ripple on the surface, there is no deformation of the surface. All that is to be seen is a perfect upside-down reflection.’ Why, in addition to seeing what was reflected in the lake, did I also see the surface which supported the reflection?

And I then started to bore her even further by conducting a series of informal experiments. I brought up a piece of paper from the foreground, which blocked off the view of the near shore, and I then brought down a piece of paper from on top which blocked off the vision of the distant shore, of which we could see the reflection in the lake, so that now all that could be seen was a sort of letterbox view of the reflective surface. Now, once I had deprived myself of the information that it was a reflection I saw, I suddenly became aware of the fact that all that I could see was an upside-down image, a paradoxically upside-down image of mountains and trees. But in the absence of the circumstantial evidence to the effect that it was a reflection, the only evidence to that effect was that it was upside-down.

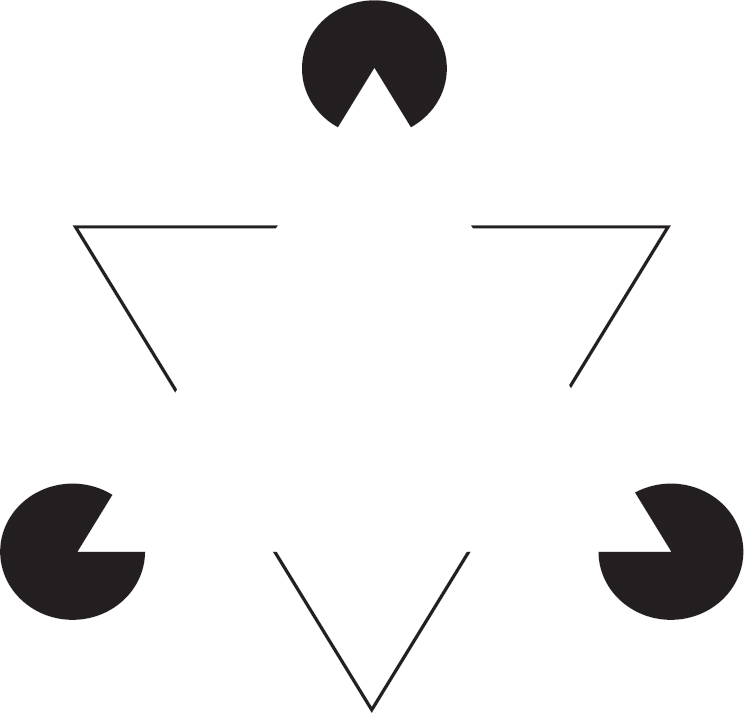

Deprived of its context, it was also, I found, deprived of its glitter. Now the sheen of the lake was no longer there, all that was to be seen was what was represented in the lake. I then became very interested in this presence of what I would describe as an illusory surface. It’s the counterpart of something which has been pointed out by experimental psychologists for a long time – started by the great Italian Gestalt psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa, who introduced something which has become the logo now for the Exploratorium in San Francisco. You know, the three black discs arranged in a triangular format, in which there are bites taken out so it looks like three Pac-Men (p. 46). Now, in addition to seeing three black discs with wedges taken out of them, you see – as a result of their configuration – something which objectively is not present, which is a white triangle overlying the three black discs, to the point that you can actually see or seem to see subjectively a contour between the edge of this non-existent triangle and the white background upon which it lies. Here you have an illusory contour.

Now, I believe that something similar is going on when you look at a reflection in a lake and when you look at a shiny surface in which you see an absolutely perfect reflection. When you are allowed to see the entire composition from which you can infer that you are in the presence of something reflected in an invisible surface, you credit that invisible surface with a presence which it otherwise doesn’t have, objectively. And this seemed to me to be a perfect metaphor for the mind. Looking at you, there, in front of me, looking up into the lights, all that I can see is what my senses deliver to me. I cannot, by inspecting my own experiences, see the grain or the substance, which actually supports this in exactly the same way as my not seeing anything in a mirror except what the mirror reflects.

I was puzzled at a very early stage, long before I sat on that lakeside, by the strange invisibility and impalpability of the apparatus I was told I had inside my head, which afforded me these experiences and competences I could undertake without having to think about them. I found myself doing sort of Wittgensteinian things: I lifted my arm without thinking what I had to do in order to lift my arm. I knew when I became a medical student that, in order to clench my fist, a necessary condition of my clenching my fist was the contraction of the muscles in my forearm. But in no way could I actually bring about the contraction of the muscles in my forearm as a prior condition of my clenching my fist. In fact, paradoxically, it seemed to be the other way around. The only way in which I could get access to the forearm muscles and make them contract was by clenching my fist. I don’t really know what I have to do in order to contract my biceps, but I know that the best way of contracting my biceps is to bend my arm against resistance. So, in other words, all of this apparatus which affords me my motor competences, all of this apparatus through which I experience the world, is in fact totally transparent to me. It is totally without physical, visible, palpable properties. And I was puzzled by this gap that lay between experience and the third-person knowledge that I had a brain inside my head which afforded me all these experiences.

So I went into neurology in order to get myself into the best third-person seat in the house, from which to see what the connection might be between having a brain and having experiences. I am still puzzled, in a way that some philosophers in Southern California seem not to be puzzled, by the fact that one of the consequences of having a brain is that one sees red and tastes coffee. Now, it seems to me that there is no problem about what David Chalmers, for example, has called the ‘psychological properties’ of having a brain: the competences that come from perceptual distinctions, memory and the sorts of things we can easily reproduce with computers.40 But there does seem to me to be an absolutely insoluble problem, and I believe it to be radically insoluble, about how it is that this stuff can actually taste coffee and see redness.

Now, I know that there’s no mystery involved. I don’t think something magical gets snuck into the system and confers experience upon an otherwise totally material setup. But I think it is probably impossible in the foreseeable future that we will solve the problem of how it is that having this rather unpromising porridge inside the skull can actually yield redness to its owner. There seems to me to be no problem about how it is that having this porridge inside the skull can yield all sorts of abilities to distinguish and press buttons when different hues of redness are exposed to the owner. That’s not a problem at all. You haven’t got to have an experience in order to do it; you can actually set up a machine which can make such discriminations. But, to quote Thomas Nagel, there is a mystery in the fact that there is something it is like to be us. As he points out, there must be something ‘it is like to be a bat.’41 Well, I think that there is something much more mysterious in that there is something it is like to be us, and I suspect that, even if I had stayed in neurology, I would have remained as puzzled today as some people are not (and I think quite unjustifiably not) puzzled that there is such a thing as redness rather than responses to a particular wavelength of light striking the retina. The problem of redness is extremely odd and one which I think people are far too confident about solving. They believe that ultimately it’s an emergent property in the way that liquidity is an emergent property of H2O molecules put together in a certain way. John Searle at Berkeley believes that consciousness emerges in exactly the same way as liquidity or conductivity emerge from certain configurations of physical matter.42

Another example cited is bioluminescence. We didn’t know how it was that a firefly or a glow-worm could switch lights on and off. Well, we solved that; we know that an enzyme called luciferase catalyzes an oxidation reaction, which releases a photon. No problem. But unfortunately there’s a curious tendency to try to equate bioluminescence and consciousness as if, in fact, consciousness were simply a brain-glow: an observable thing, an emergent property which came out of putting together matter in a certain way. So we have this weird, paradoxical situation, in that we know that it’s nothing other than matter put together in a peculiar way, but the idea that matter put together in a peculiar way can yield content and excitement and things like redness and coffee seem to me to be beyond our understanding at the moment, and I suspect beyond our understanding at any future moment that we can imagine.

Nevertheless, it seemed worthwhile to go on in neurology even if, in fact, the problem of experience, the problem that the philosophers call qualia would remain insoluble. There was lots of other work to be done, and it was not, as Patricia and Paul Churchland at University of California San Diego insist, a counsel of despair to say that this would never be solved.43 There’s plenty of work to be done – we will approach this problem asymptotically and never arrive at it, but en route to it all sorts of extremely interesting things will be solved with regard to our ability to calculate, to remember, to distinguish colours, and so on and so forth. And also to raise our arms without being able to contract our muscles knowingly.

Now, what on earth connection could all that have to the theatre? Well, one of the things which became clearly apparent to me was that the work I did as a diagnostician in neurology sensitized me to the demeanour of people. A good clinical neurologist could probably do 30 per cent of the diagnosis by the time patients have got from the door to the chair, and could do it without having to use any sort of technical instrument but by merely watching the demeanour, the behaviour, the gait, the facial expression, and the way in which they address him and give an account of their illness. In fact, the performance of a patient sensitizes you to behaviour in a way that is completely transferrable, wholesale transferrable, to the theatre.

What are we doing in the theatre? We are getting people to pretend to be people they are not, which is very hard to do. You watch actors down in the canteen after they have rehearsed – and usually rehearsed very badly – trying to be someone they’re not, but down in the canteen they are totally at ease with themselves when they order coffee and talk to their fellows about what they’re going to do next. One is immediately struck by the peculiar discrepancy between being yourself and pretending to be someone else. And what it is that actually happens, as you rehearse and get better at being someone you are not, starts to concentrate the mind wonderfully on the problem of what it is to be oneself in the first place. Once you start getting people to pretend to be someone they’re not you have to start breaking down the modules of behaviour, and it focusses your attention on the spontaneous performance of self because you’re actually asking people to pretend to be selves that they’re not. And you can watch the incompetences, the failures of performance of an actor, in exactly the same way as you watch the failures of performance of a damaged patient. I’m not saying that actors are damaged, but actors are ‘damaged’ until such moments that they have actually gone onto the stage with what they believe to be – and what the audience agrees to be – a satisfactory performance. There is a long period of individualism between the moment when they are given the text and yield the final performance. And by observing that long invalid period when they are handed a text consisting of lines which have not occurred to them but for which they have to give the audience the impression of uttering and meaning them – in that long invalid period, by watching what it is that goes into that incompetence, you learn something about what competence itself consists of.

So there was an almost seamless transition for me. I found there was no awkwardness or difficulty or inconsistency about having watched damaged patients whose motor systems were off, damaged patients who were unable to recognize their relatives, and watching actors. All of these things which I saw in neurology seemed to have a bearing upon the things that people were doing when they were rehearsing. I also found a very interesting reciprocity between being a doctor and being a director: in addition to finding that the work of observation – which I had been trained to perform as a neurologist – lent efficiency to my directing, I also found that the observations I made in the rehearsal room could feed back into clinical work. I found myself going back to the wards and seeing things my clinical colleagues had missed. People often say, ‘Well, of course, the reason why a doctor finds it so easy to be a director is that you’re dealing with mad people, disordered people. We all know actors are potty in some way.’ It’s got nothing to do with that. Actors are not potty; actors are perfectly ordinary and often rather humdrum people who sometimes spring into a more colourful existence when they’re pretending to be someone other than themselves. But that’s not the appeal. The appeal is not that you could help people – actors – who are damaged, but rather that, in seeing people who can’t quite get round being someone else, you are actually focusing on what goes into being a self in the first place. So I went into the theatre. I found it a very intellectually profitable way of simply extending the work that I was trained for in the years that I had actually been studying clinical neurology.

The rest of my work time in the theatre I spent working on what one could loosely call ‘the classics.’ I worked on texts, on scores, which are inherited from the relatively distant past, works which probably have had a longer posterity than their makers could have imagined. It’s extremely unlikely that Monteverdi and Shakespeare ever in their wildest dreams imagined that their works would be bequeathed to others who were so fundamentally and recognizably different from them and from their audiences. It’s very hard to put ourselves back into the imaginations of people in the sixteenth or seventeenth century and to conceive the notion of posterity as visualized by them. We know that most works were, in fact, composed for the occasion, so we have this rather peculiar and interesting philosophical problem of what to do with works intended for an occasion, and which have been retrieved and revived and undone by people who are utterly different from the people for whom the works were intended.

The phrase I constantly invoke in describing this is what I call the ‘afterlife’ of plays and operas. With very few exceptions, I think you can say that almost all forms of art have what you might call their natural life – a life for which they were intended, an audience for whom they were intended. And then at some time which is very difficult to date accurately – and it may not even be reasonable to want to date it accurately – they enter something which you could loosely call their afterlife. They are now being seen and visualized and retrieved and valued and reconstituted for reasons completely different from the reason for which they were composed and enjoyed at the time they were done. So there is a deep procedural problem about what to do with these works from the distant past, which fall into our world like meteorites from another part of the cosmos. I became fascinated by the problem of how to perform something when you don’t know what it was intended for originally and what the sensibility was of those to whom it was delivered.

I sometimes think that it’s very similar to the distinction that was made in 1903 by the geneticist Wilhelm Johannsen, who distinguished between genotypes and phenotypes.44 What you have in the form of a text or a score is something like a genetic instruction. It’s a promissory note with a view to something which will be created by obeying the instructions. But what in fact is created as a result of following the instructions depends, as it does in biological organisms, on the environment for which those instructions are delivered. Subsequent performances of the dramatic phenotype will often be profoundly different on successive performances from the performance that was generated by the same genetic instructions at the origin.

This poses a deep and interesting problem about transformation and interpretation. Audiences – particularly in the United States where they’re very conservative about opera – who believe that there is a standard phenotype which ought to be preserved at all costs, become terribly restless when it’s not preserved. They believe that the genotype tells you what the phenotype should look like, and that the phenotype should be preserved as it was at the origin. But of course very few people have any idea what the original archetypal phenotype looked like. We don’t know what the first night of Twelfth Night (1602) looked or sounded like at all. All that we have is this sort of rough DNA which has come down to us imprisoned in literary amber, which we can, as it were, prise out and put into modern actors and create a Jurassic Park of modern drama. There’s no way we can ever backtrack to the original phenotype because we don’t know what it looked like, and we certainly don’t know what it sounded like. There are only very incomplete reports of what the earliest performance of The Marriage of Figaro (1786), for example, was like. There’s no way of knowing. And indeed if there were a way of knowing, there is a deep perceptual problem about how you obey the instructions of the phenotype as exemplified by a record.

Let me tell you what I mean by that. The problem is raised most acutely by forgery, which, in a way, is the prototype of the faithful performance of the original phenotype. Now, doing operas is a very expensive business, so you cannot afford to junk the performance of any given after the inaugural run. You’ve spent so much money costuming it and designing it and simply putting it on the stage the first time, that you have to go on reviving it at successive intervals. What you do is write down a series of parallel instructions, in addition to the score you inherit from Mozart or from Verdi. There’s a prompt book, which says: ‘A moves downstage left, sits down, and turns contemptuously towards B.’ And after the first year, by reading those circumstantial prompt-book instructions, you can reconstitute an approximation of that inaugural phenotype of the performance of that particular production. After about four or five years, when the instructions in the prompt book are no longer being read by someone who was there at the time they were written down, it becomes extremely problematic as to what those instructions really mean. You can work out mechanically what they mean. A little arrow pencilled in shows A moving downstage left, and you can say, ‘Well, darling, what you do is you move downstage left,’ and then the actor or the singer will turn to you and say, ‘Well, why do I move downstage left at this point?’ And you look it up and say, ‘Oh it doesn’t say. It doesn’t say why.’

What would have happened if we had had a perfect, faithful videotape of the first night of Twelfth Night? Well, there is an interesting perceptual problem in copying a performance which is visually in front of your eyes and ears at the time, and there is a deep procedural problem about what goes into copying something. To use Nelson Goodman’s term, what do you think the example exemplifies?45 Which aspect of it is important? More often than not, you may have at your disposal in the first three or four years an assistant or a stage manager who was present at the time of the original performance who could say, ‘Oh, what you see on the videotape here does not exemplify what people wanted in that inaugural performance; it’s a fault. It’s something which is not a realization of what was intended. It’s a genetic error, a misprint, a mistranslation of the instructions.’

Now, what happens when people consult the videotape 15 or 20 years later? How do they know which part of it is, in fact, the part which ought to be copied? They have to start looking at it with a view to what they think is interesting in the example, and this brings me back to the question of forgery. Forgeries are by definition the prototype and the epitome of the faithful phenotypic reproduction. All forgeries become apparent after about 30 or 40 years. Why? The most interesting illustration about that is the story of van Meegeren’s forgeries of Vermeer during the Thirties. Van Meegeren was an envious, failed artist, who felt that the only way in which he could attract attention, or prove to a disbelieving art world that he was, in fact, a genius of some sort, was forgery. Since people didn’t like his original work, he said, ‘Well, I will show how good I am by reproducing a work of someone who is widely admired, which will thereby prove that I’m as good as he is. I will do Vermeers.’

Now, there’s no point in doing Vermeers everyone knows already because they would obviously be copies of Vermeers, so what he had to do was produce original Vermeers. When he delivered his original Vermeers, the art establishment in The Hague was taken in by the paintings and said, ‘These are indeed interesting examples of the early Vermeer of the period of Christ in the House of Mary and Martha [1655]’ (which you can see in the Edinburgh Gallery). And then something rather fascinating happened: he stupidly sold a couple of his pictures to the Germans, so that in 1945 he was had up in front of a Dutch court for collaboration, for selling a national treasure to an occupying army. Van Meegeren now had to say, ‘Well look, no, those are in fact by me. I was not selling Vermeers. I was only selling van Meegerens and who cares a damn?’ The court then said, ‘Well, prove it.’ So he painted another van Meegeren. Now here something deeply intriguing happened, as Nelson Goodman points out in The Languages of Art (1968). In the knowledge that these two or three he had done were, in fact, van Meegerens, the genuine Vermeers which were previously seen as imperceptibly the same as his forged Vermeers now became quite clearly distinguishable.46 Now, this isn’t because people were just being wise after the event. Rather more interestingly, it shows what goes into being wise after the event, what being wise after the event consists of perceptually. And as Goodman points out, once you have circumstantial, independent evidence to the effect that groups A, B and C are van Meegerens, whereas the groups from D to M are in fact true examples of Vermeer, you can see it. Once you have a perceptual incentive to see the difference, the difference is glaringly apparent.

Now, this is related to something the great Harvard taxonomist and systematist Ernst Mayr pointed out. During the 1930s fireflies in the Caribbean comprised no more than about four or five different species, based on morphological grounds. After the Second World War, new electronic methods of recording the flash frequencies of fireflies showed that on flash-frequency criteria there were at least 14 or 15 different species. When the flies were caught and sorted into enamelled trays according to their flash frequencies, morphological differences which had previously passed unnoticed suddenly showed that there were as many species on morphological criteria as there were on flash-frequency criteria. In other words, there was a perceptual incentive to look for differences that had previously passed unnoticed.47

Something very similar happened with Gilbert White, the author of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1789). Two types of hedge bird, what we now know as the meadow warbler and the pippit, had previously been regarded as members of one species. When White observed them more closely and noticed that there were two song patterns, it became apparent that what had been thought to be one species actually split morphologically into two.48 And that’s exactly what was happening, I think, in the case of the Vermeers and van Meegerens.

Now, this is a roundabout route to asking the deeper question: why is it that now, more than 50 years later, anyone – not just an art historical expert, but anyone – going down into the basement of the Rijksmuseum and looking at van Meegeren’s Vermeer forgeries will wonder, ‘How was anyone ever taken in by it?’ Again, this is not simply being wise after the event. Something much more fundamental is happening than what Goodman pointed out on the first occasion when the distinction was made. Why is it that people now, 50 years later, say, ‘These are quite clearly not Vermeers.’ They may not know that they’re by someone trivial like van Meegeren, but they know that they’re not Vermeers. It is clearly apparent by 1990 that they’re not Vermeers, and the reason is simply this: that what people thought Vermeer exemplified and what in Vermeer a forger thought was worth copying in 1932 were completely different from what people thought worth copying, even to the point of being indistinguishable, in 1990. So that even though the name of the game in forgery is indistinguishability, the forgeries become distinguishable with the passage of time, because time brings in a different view of what you think you are copying and what you are doing by copying something. In the act of copying something you are introducing a perceptual bias, some sort of idea of what you think is exemplified by the prototype – what you think is valuable in it, what is worth reproducing in it.

If that’s the case with something like an autographic work, think how much truer it is when it comes to something Goodman has described as an allographic work, one that doesn’t depend on reproducing an artefact but on simply obeying a series of verbal instructions with a view to a performance.49 After all, there is a sense in which Hamlet doesn’t exist between its successive performances. It exists in the form of these genetic instructions, but they’re fixed in amber in the library. They can be read by people, but Hamlet itself in some plenary form doesn’t exist until it is brought into intermittent and successive realization in performance. But the problem is how do you obey the genetic instructions? What do you think the genetic instructions exemplify? This deep interpretive problem arises with the passage of time. But even if you take the instructions and reproduce every single word of Hamlet, why is it that successive versions of the play look so different? Because what we think the text exemplifies, what we think it is an instance of, will vary with the passage of time.

This happens with anything that we inherit from the distant past. All of these works are in their afterlives. We value them for reasons totally different from the reasons they were valued by their maker, and also for reasons very different from the reasons they were valued by their audiences at the time they were first seen. Think of the Belvedere torso in the Vatican Museums in Rome – this armless, legless object; this strange, luminous, twisted torso which has no limbs at all. We know perfectly well that the author of that work would be extremely distressed to find it in that form. He would have to say, ‘Well, you should have seen it when it had its arms. I’m very disappointed to think that you’re exhibiting this mutilated version. It scarcely counts as an instance of my work.’ And yet, in some odd way, it is in that mutilated version that we cherish it, so much so that we would be deeply distressed, I suspect, if by some sort of radiocarbon dating method we could find the original arms and put them back on again. There would be a sense that in some way it had been violated just as much as was the Michelangelo Pieta in the Vatican with its nose knocked off. The restoration is often seen by us as almost as much a destruction as a mutilation, and that is because it has entered our lives in the form that it has. Rodin, inspired by such mutilation, made some of his statues limbless or headless or armless because he got excited by the very form in which the work actually entered its afterlife.

I think any responsible director in the theatre, sort of like a plant breeder, takes these strange genetic instructions from the distant past and makes them into something intriguing and interesting to an audience in the late twentieth century; makes them recognizable. I don’t want to use the word ‘relevant’ because I think relevance actually means that it always has to address current problems. I don’t think things from the past are made interesting by torturing them until they deliver some sort of confidence about our situation. This is an example of what T. S. Eliot called the overvaluing of our own times, as if the works from the past exist in a sort of probationary relationship to our own times, as if they are interesting only insofar as they can address our problems.50 That’s going to the other extreme. I think there must be some way in which we actually treat them as alien objects, as something coming from something else, from elsewhen, from elsewhere; but nevertheless, unavoidably, they have to be treated as if they’re going to interest us in some way without necessarily addressing our current interests. Not every version of a Verdi opera has to be set – as so many German colleagues of mine do it – in a concentration camp in order to be interesting to us. But there are ways of reconstructing and, God forbid, deconstructing them – one of the hideous new trends in the theatre these days. It’s as if the genetic instructions are bequeathed to the modern director, who then does a lot of genetic engineering on the instructions themselves and actually transplants things and makes them mean something totally different from what they might have meant at the time. But I think there is a generic range of meaning that things might have, and if you go beyond that, you make a shambles of the work.

As I near my retirement from the theatre, I find myself confronted by this very peculiar problem of dealing with works which come from a long time ago.51 One of the paradoxes of modernity is that it is characterized by extraordinary archival obsession with its inheritance. In 1700 no one would have expected to see a performance of a play or an opera which came from a hundred years earlier. Monteverdi was not performed for 300 years. He went into some sort of peculiar aesthetic hibernation. The idea of performing Monteverdi 25 years after his death would have been completely inconceivable, just as it would have been inconceivable to have performed something from 100 years earlier. Why is it that we are so fascinated with retrieving these works from the past, and why is it possible to go to a concert hall or an opera house and see works from three successive centuries in the same evening sometimes? You can get a work by Monteverdi and a work by Schoenberg performed in the same evening.

But a culture so energetically retentive and so eager to bring stuff back from the distant past makes problems for directors, producers and audiences. I think the audience has made the problem even harder for itself by insisting on the idea that there is a standard phenotype which must be preserved at all costs. In very big opera houses, such as the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where I’ve worked several times, audiences are deeply disturbed if they see a ‘classic,’ as they call it, transposed in some way – if they don’t see lavish scenery, if they don’t see what they think was the original phenotype on the stage. They have every reason to think that it was the original phenotype because they don’t know what the original nineteenth-century version of Verdi looked like. I suspect they would probably be horrified by what went on in the nineteenth century. What happens is that modern audiences have another sort of psychological process going on not unlike Konrad Lorenz’s imprinting of geese. What the audience thinks is the orthodox performance turns out merely to be the performance by which they were ‘imprinted’ the first time they were exposed to it. In exactly the same way as you can get a greylag goose to court a wastepaper basket (if that’s the first thing it’s exposed to, it will go on courting a wastepaper basket in exactly the same way), modern audiences will go on courting the operatic equivalent of wastepaper baskets in the form of a prototype of the first time they saw Il Trovatore (1853). If it departs from that, they think it’s departing from orthodoxy. It’s not. It’s departing from what they were imprinted by, and the difference between that imprinting experience and the inaugural performance is probably very profound. If you were to compare the version they were imprinted by and found satisfactory, it would probably bear a very marginal relationship to what they think was the inaugural one.