Self-recognition

On Reflection, 1998214

In 1998, Miller curated Mirror Image, an exhibition at the National Gallery which focused on the pictorial representation of reflection. In this extract from the accompanying book, he considers the ability to recognize oneself.

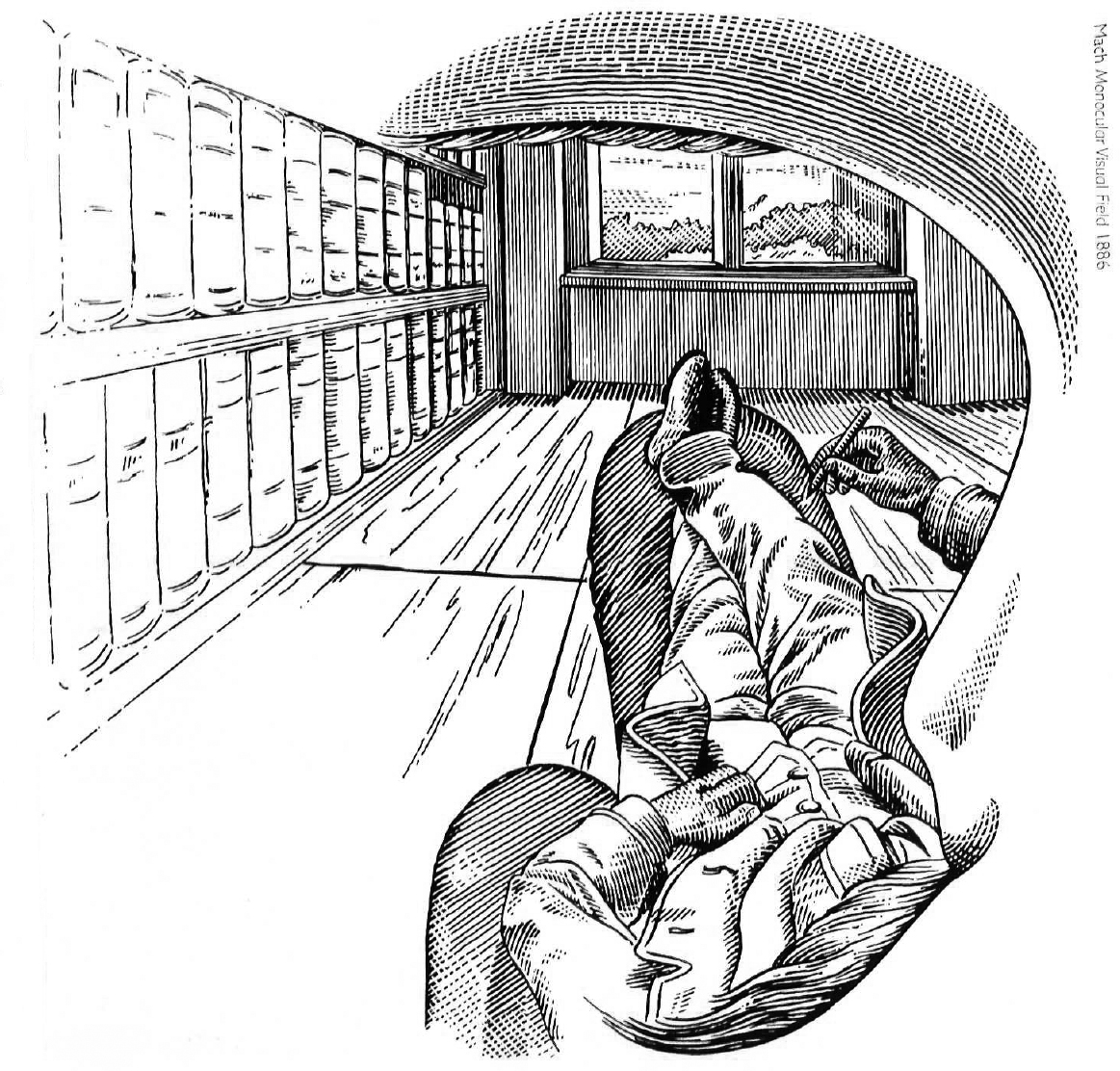

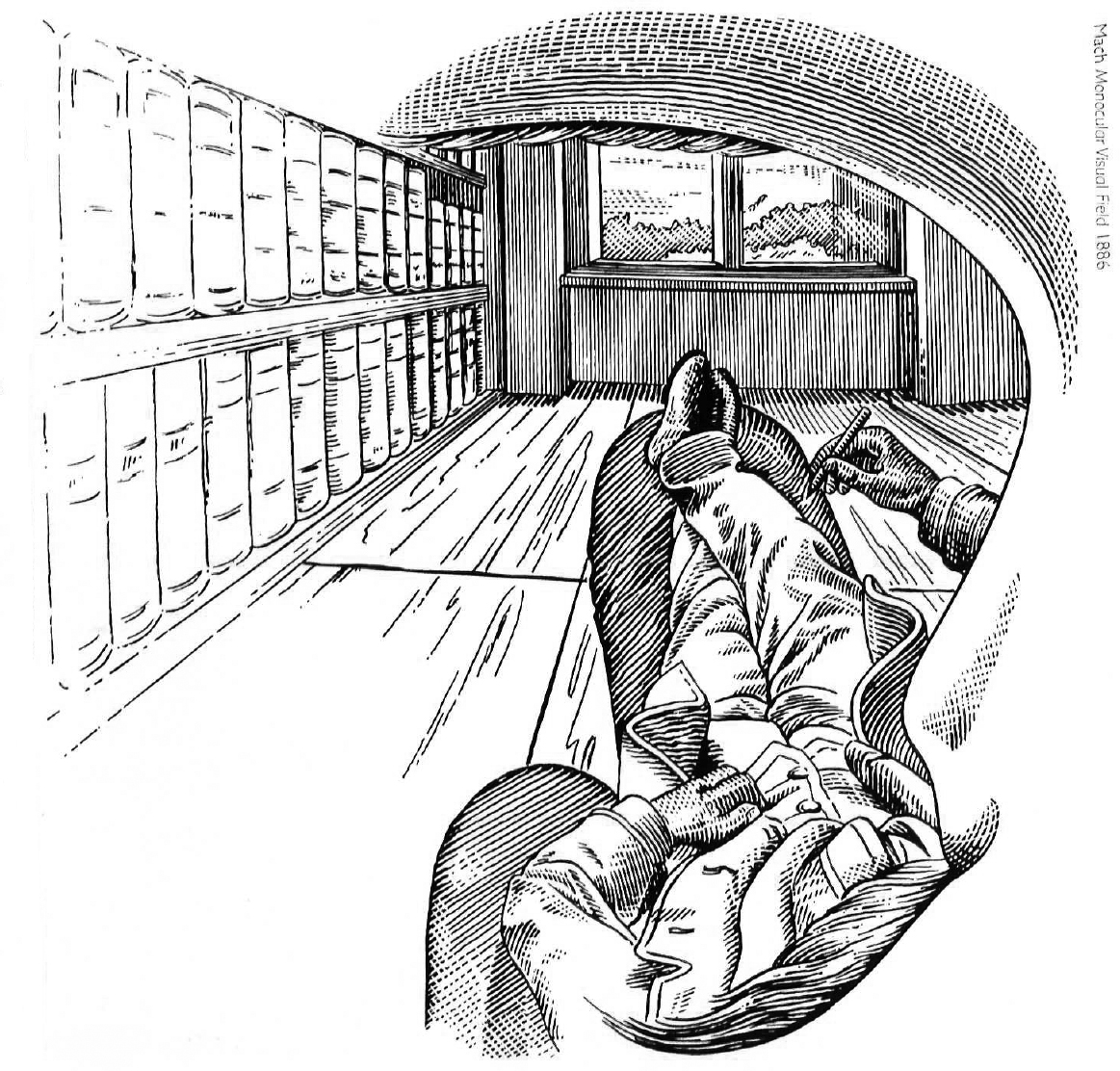

In 1886 the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach sat down in a chaise longue and drew a simplified sketch of everything he could see with one eye closed and the other fixed on a point at the far end of his room. In many respects the drawing is a misleading representation of what someone would see under such conditions. As we have already seen, the visual field does not have such sharply-defined edges and since the retina does not record visual details uniformly, Mach’s sketch shows more resolution than it should. Nevertheless it truthfully includes something which we normally overlook: the extent to which our own physique intrudes on the visual field. Under normal circumstances we are completely unaware of the edge of our own nose and unless we undertake a manual task which requires visual control, we pay little or no attention to the way in which our arms intrude upon the circumference of the visual field. So in this sense Mach’s sketch draws attention to a neglected aspect of visual experience. Even so, his picture is somewhat misleading since it reveals both more and less of ourselves than we normally see. If we are standing upright, looking straight ahead with our hands down at our sides, it is almost impossible to catch sight of ourselves at all. But conversely, by turning our head this way and that – up, down, right and left – we can take in much more of our own physique than Mach did at his artificially single glance.

But if we make an allowance for the way in which the drawing forgivably misrepresents the visual appearance of our own body, it draws attention to the fact that no matter how much we can see of our own physique – try as we may, twist and turn – the part by which we would expect to be identified and recognisably portrayed is inescapably invisible, and that without the help of a mirror we would never be acquainted with the appearance of our own face. If we lived in a world without reflections, self-portraits would be inconceivable – or else they would have the strangely beheaded appearance represented by Mach.

How then do we succeed in recognizing our own reflection when we do catch sight of it? If we don’t know what we look like until we see ourselves in the mirror, how can we tell, when we do see it for the first time, that the reflected face is ours?

One answer might be that in recognizing everything else that appears in the mirror as a duplicate of what we can see around us, we might deduce the identity of our own reflection by a process of elimination, since it would be the one item appearing in the mirror for which there was no counterpart in the immediate environment.

A much more significant clue about the identity of our own mirror image is the fact that its behaviour is perfectly synchronized with our own. Remember the famous scene in Duck Soup. But wait… If our facial behaviour is invisible, how can we tell that it is synchronized with the expressions we can see in the mirror? For the simple reason that we are directly acquainted with our own actions, facial or otherwise, without having to see them. I know that I am smiling, waving or frowning, not because I can see myself, but because I can feel it. Each of us has a so-called kinaesthetic sense of our own muscular activity. This sixth sense is based on two sources of information, only one of which is strictly sensory. When we move intentionally, the nerve impulses which are despatched to the appropriate muscles leave a copy of themselves in our central nervous system, so that we have a more or less conscious representation of the forthcoming movement. Since the ensuing action is then monitored by sense organs embedded in the muscles and joints which execute the gesture, we have detailed information about what we are going to do and about what we have just done. So, confronted by what happens to be our own reflection, we can recognize a correspondence between the actions of which we know or feel ourselves to be the author, and the visible movements in the mirror with which these muscular feelings are so accurately synchronized.

However, the fact that something changes its appearance in time with our own actions does not necessarily mean that we would recognize it as our own image. It is easy to imagine an experimental set-up in which an artificial configuration of squares, discs and rectangles was wired up to a television camera in such a way that it changed its appearance in step with changes in the facial expressions of the subject, who would inevitably recognize that there was a causal relationship between his own facial expressions and the mechanical movements of the Calder-like mobile in front of him.215 But that would not lead him to think that he was seeing his own reflection. In order to identify with an image, as opposed to recognizing a causal relationship with it, the subject would have to recognize that there was a fundamental resemblance between him and it. In other words, he would have to see it as the same type of thing as himself and that there was an anatomical equivalence between some of its moving parts and some of his own. All this takes care of itself when and if the individual can see his own moving parts – in other words, the parts Mach could see when he looked at himself without the help of a mirror. For example, if I move my arm and can see myself doing so without the aid of a mirror, I have something visible with which to compare the visible movements of the reflected arm. If they look alike and move at the same time as one another, chances are that they are one and the same thing, and that I am in fact looking at myself. But when it comes to parts of myself which I cannot see without the aid of reflection – my face – then there is a problem. Admittedly I can feel the difference between opening my mouth and poking out my tongue, but how can I tell that what I can feel but not see myself poking out corresponds to what I can see but not feel poking out in the mirror? The fact that I can tell, indicates that I have an anatomical representation of my face, albeit a non-visual one, and that I can accurately map its ‘felt’ parts on to the corresponding features of a visually represented face. It could be argued that this correspondence has to be learned, but there is experimental evidence to show that it is innate.

In at least one study it has been shown that in the first ten minutes of life a newborn infant will follow or ‘track’ a face-like pattern in preference to a ‘scrambled’ one. Further research has shown that the infant reacts to such patterns as if it recognized the anatomical correspondence between the as yet invisible features of its own face and the visible features of someone else’s. In 1977, Andrew Meltzoff and Keith Moore demonstrated that within the first few weeks of neonatal life, an infant will discriminatingly mimic the facial expressions of an adult.216 That is to say, in addition to following a face with her eyes, the newborn infant will respond to the sight of someone protruding his tongue by poking out her own. If the adult gapes, the infant will accurately copy the expression with her own mouth. In order to rule out the possibility that this might be a crude reflex response, Meltzoff momentarily frustrated the reaction by putting a dummy or pacifier in the infant’s mouth immediately before it was shown the test expression. In spite of the fact that the adult carefully assumed a neutral expression just before removing the dummy, the infant mimicked what she had just seen but had been prevented from responding to a moment earlier. It was as if she had retained a visual record of the mouth opening and then imitated it from memory.

All in all, then, the newborn infant a. can distinguish a human face as something peculiarly interesting b. can tell that someone else’s face is sufficiently like her own to merit playful interaction c. in spite of the fact that she is unacquainted with the appearance of her own face, she can recognize the correspondence between the parts of herself that she can feel and the equivalent parts of someone else that she can see. In reacting imitatively to something which she recognizes as similar to herself, the infant is halfway towards recognizing something which happens to be identical to herself: her own reflection. All the same, it takes at least 16 months, and sometimes as many as 24, before the infant does recognize her own reflection. The method by which she does so is largely experimental. She plays games with her own reflection; challenges it almost. On finding that its behaviour is accurately synchronized with her own, she comes to the inescapable conclusion that she is looking at herself.

But what exactly does that mean? The statement ‘Rosie recognizes that she is looking at herself’ presupposes that Rosie is aware of something other than the reflection: namely, the ‘self’ with which she identifies it. The difficulty is that in contrast to all the other entities about which it is possible to make intelligible statements as to what they do or do not resemble, it is devilishly difficult to say what a self is, let alone what awareness of it consists of. Suffice it to say that the ability to identify ourselves in a mirror presupposes a distinctive form of consciousness – namely self-consciousness – and that human beings display it or have it to a remarkable degree.

However, the fact that human beings are endowed with a high level of self-consciousness does not necessarily mean that the privilege is confined to Homo sapiens. If it is a privilege – that is to say if having it confers a selective advantage and, as I shall argue later, there are reasons for thinking that it does – then we would expect to find traces of it in some of our closer relatives, perhaps even developed to the point where they too could identify themselves in the mirror.

As it happens, there is only one other primate species in which self-recognition is unanimously agreed to exist. Although comparable claims have been made for orangutans, for ‘one’ domesticated gorilla and even (predictably) for dolphins, the chimpanzee is the only other animal for which the evidence seems to be uncontroversial. The first experimental tests were carried out by Gordon Gallup in 1970.217 He took a group of young chimpanzees reared in captivity and placed them in cages equipped with a large mirror. To begin with they reacted to their own reflections as if they were other members of their own species, displaying social and sometimes aggressive behaviour. On other occasions they investigated the mirror itself, poking it and looking behind. After a few hours they began to behave as if they understood that their own actions were the cause of the reflected ones. Before long they began to use the mirror to inspect parts of their own body which would not otherwise have been visible: the inside of the mouth, the soles of the feet, etc. As Gallup goes on to say:

In an attempt to validate my impressions of what had transpired, I devised a more rigorous, unobtrusive test of self-recognition. After the tenth day of mirror exposure the chimpanzees were placed under anaesthesia and removed from their cage. While the animals were unconscious I applied a bright red, odorless, alcohol-soluble dye to the uppermost portion of an eyebrow ridge and the top half of the opposite ear. The subjects were then returned to their cages […] and allowed to recover. […] Upon seeing themselves in the mirror the chimpanzees all reached up and attempted to touch the marks directly while intently watching the reflection. […] In addition to these mark-directed responses there was also an abrupt, threefold increase in the amount of time spent viewing their reflection in the mirror.218

Gallup noted that when the same procedures were applied to various species of monkeys – macaques, etc. – none of them went beyond the first stage; they continued to react to their reflections as if they had seen another animal of the same species.

Apart from the fact that the natural opportunities for doing so are few and far between, it is difficult to imagine the biological advantage of a chimpanzee’s being able to recognize its own reflection. This must mean that the skill which is so readily demonstrable in captive chimps can only be the unforeseen and functionless by-product of a capability which was selected for its usefulness. What could that have been? The most likely candidate is the one mentioned above: self-consciousness. In a sociable species whose individual members are bound to one another in a complex web of cooperation and competition, it might be a matter of some importance for the individual to recognize himself as the target for the same sort of Machiavellian designs that he entertains towards his fellows. In order to strike the most profitable balance between trust and suspicion, probity and deceit, it seems reasonable to suppose that the chimpanzee might develop or inherit a wordless hypothesis whose unstated premise is that members of his own species are fundamentally irrational – scheming, believing, desiring and expecting, just as he is himself. Since Premack and Woodruff’s classic paper of 1978, this notion has been generally referred to as the ‘theory of mind,’ by which is meant a theory about the possession of mental states by individuals other than oneself.219 The selective advantage of entertaining such a theory is almost self-evident, since it puts the individual in a position to predict and make allowances for the self-promoting schemes of others. It presupposes, and to some extent is constituted by, an awareness of oneself as an agent and as a believer. One of the consequences of such profitable levels of self-consciousness seems to be the predictable though biologically functionless interest in one’s own reflected image.

But it would be rash to assume that the degree of self-consciousness sufficient to account for self-recognition necessarily implies the possession of a ‘theory of mind.’ The controversy still rages as to the extent or even existence of such a theory in the higher apes. But when it comes to two-year-old human infants, the evidence seems to support the belief that the moment of self-recognition coincides with the appearance of behaviour that can only be explained on the assumption that the child has a mental representation of the beliefs, wishes and interests of others. As far as some psychologists are concerned, failure to pass the mirror test by 24 months is taken to be a diagnostic sign of incipient autism, a condition which, as its name implies, is characterized by the inability to represent the mental life of others.

In contrast to chimpanzees who would not normally encounter their own reflections, whose self-recognition has to be experimentally induced, most human beings are born into a culture in which the mirror is already a significant artefact and where the act of self-inspection is so spontaneous and so recurrent that it figures as a prominent and varied motif both in literature and the visual arts.

With rare exceptions, the inaugural encounter between a child and its own reflection is never represented, and it is difficult to think of a painting in which mirror-gazing is represented as something prompted by objective curiosity, as if to say ‘How odd, here I am and there I am again.’ Broadly speaking, when human beings are represented in explicit relationship to their own mirror images the pictures fall into two recognisably distinct categories.

a. Ethically neutral, non-judgemental representations in which the mirror figures as one of many household appliances with which the individual might be engaged in daily life.

b. Moralising tableaux in which the subjects’ preoccupation with their reflection is represented as the personification of either a vice or a virtue.

In genre paintings, the figure – almost invariably a woman – is using a mirror to check or change her appearance. The tone of such paintings is relaxed and easy-going and in most examples the subject is quite literally at home with her own reflection. Without any implied moral comment the act of self-adornment is represented as one of many domestic tasks dedicated to the blameless upkeep of appearances.

As Anne Hollander points out, in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings the mirror is characteristically small and reflects little more than the subject’s face.220 To a large extent this must have been because of the unavailability of larger mirrors, but, by the nineteenth century, paintings and photographs show women examining themselves at full length. Although the larger mirrors revealed parts of the body which would have been visible without the aid of reflection, they did so from a viewpoint quite different from the one from which the subject would have seen herself without the aid of a mirror. As Mach’s drawing shows only too well, the unaided view of our own extremities is steeply foreshortened, whereas the reflected view, being at a right-angle to the long axis of the body, corresponds to the appearance we have for others. By posing in front of a full-length mirror, the subject stages her social appearance and can rehearse the improvements as she would like them to be seen by her fellows. It is interesting to note that the sort of activities for which the mirror is necessary are characteristically the ones for which visual control is absolutely essential; that is to say, ones in which the effects of the actions cannot be judged without seeing them. Of course, there are many interactions between the face and the hand for which the visibility of neither is required. We can effectively blow our nose in the dark and accurately cup our hands to our ears without having to watch ourselves doing so. Dining tables do not have to be equipped with mirrors in order to guarantee the successful outcome of a meal. But when it comes to adjustments of personal appearance, reflection is the only way in which success can be judged. In tribal societies whose members employ elaborate forms of self-decoration, the absence of a mirror meant that each individual had to submit himself to the cosmetic skills of someone else. It was only with the arrival of European traders that self-adornment was increasingly performed with the aid of reflection.

Although many of the paintings that include mirrors are ethically neutral, they grade imperceptibly into representations in which there is an unmistakably moral attitude to the act of self-regard. Without any explicit statement to that effect, the disapproval is conveyed by the expression of self-satisfaction on the subject’s face, or, as in many of Balthus’s paintings, by a look of rapt entrancement. And in some cases the self-indulgence is collusively encouraged by smiling attendants. In such pictures the reflective surface is implicitly represented as a seductive trap in which self-regard can lead to culpable self-satisfaction.