Subsequent Performances, 1986302

Before rehearsals begin, I will have worked on a metaphorical level looking for similarities and affinities between the structures in the play and other works of art of the period. But these are very preliminary intimations of what might happen in the rehearsal period – sketches and suggestions about how things might proceed. They introduce guidance and limitations but not tyrannies. The director who approaches the work having apparently imagined everything has literally conceived everything but imagined nothing, thus missing the crucial point of directing: you must imagine very richly but you must also be capable of conceding, admitting and allowing to the same degree. It may be that actors regret, and resent, that they have not taken this initiative, and see themselves as objets trouvés assembled by the director in a collage of his making. But I do not think that this is a fair assessment because, although they are objets trouvés to the extent that the director identifies particular properties they have before the play starts, the actors show all sorts of completely unexpected features which develop in the course of rehearsal. It is nearly always the case that the director is surprised by what the actors bring to rehearsal. What follows is adaptation and discussion, and these two words describe the process of directing itself.

I like to let people start reading the play, and to wait for alternative inflexions to appear during the course of rehearsal, which I then edit, revise and emphasize. In this way salient features can emerge, or be introduced, as the production grows. I used to begin rehearsals with some long erudite lecture, but now I say less and less. I show the set, hand round the costume drawings and give thumbnail sketches of what I think the characters might be, and why I have chosen particular actors for the parts. People tend to believe in the pre-existence of the fictional characters, and mistakenly think of rehearsals as nothing more than the process of bringing these characters back to life. But I start out the rehearsals treating the speeches in the text as if they are premises-to-let that are to be occupied by persons as yet unknown. When casting, I may have advertised for a particular type of tenant but I cannot tell exactly how they will inhabit the role.

During rehearsals, the director and actors make visible something that is there but in some way obscured. The only point that I ever emphasize now is that the characters – Hamlet, Claudius, Troilus, Cleopatra, or whoever – are extremely indeterminate people. They are signposts pointing in a certain direction; indications of where there might be a character if the rehearsals go well and they come into existence. Another analogy, which I think of in order to describe rehearsals to myself, is that they are like séances. In the process of getting the actors to speak their lines, characters begin to take possession and to inhabit the speeches. By the time the rehearsals come to an end, the lines seem to be spoken by someone with whom the actor was unfamiliar at the outset but has come to know in the process of speaking the lines. As a director who is outside the play, for whom the lines have an objective existence, I have vague intimations as to what is in them but defer to and rely on the actors to bring characters out of those lines. It is only by inhabiting the lines, by being inside them, by speaking them and beginning to act through them that a direct knowledge of what they mean emerges in rehearsal.

The language we speak spontaneously, like the language that has been written down for someone else to speak artificially, has a double existence. The words have an objective existence for an outside hearer, who may infer something about what is meant by them, but they also have a subjective existence for anyone who speaks them. Obviously, their subjective existence is spontaneously created by the speaker because he or she knows what it is he or she wants to convey by speaking them. In the case of lines that preexist, because an author has left them behind him, their subjective identity has to be discovered by the conjectural process of speaking them. Merely reading a speech does not always tell you what is possible in the lines. Their full possibilities cannot become apparent until they are spoken.

An actor is someone whose imagination is galvanized and stimulated by taking the plunge and inhabiting the lines from within, not by reading them from the outside. Often the actor begins to make discoveries only by taking the risk of speaking the lines without having the faintest idea of what they mean. It is then the director’s responsibility to notice and encourage consistent or interesting trends developing in the diction. In this way, confusing, conflicting or less interesting alternatives are gradually whittled away so that a cleft is made in the language. As the rehearsals continue, and the director encourages one implication rather than another, meaning opens out rather as if you have made fissures in the language itself.

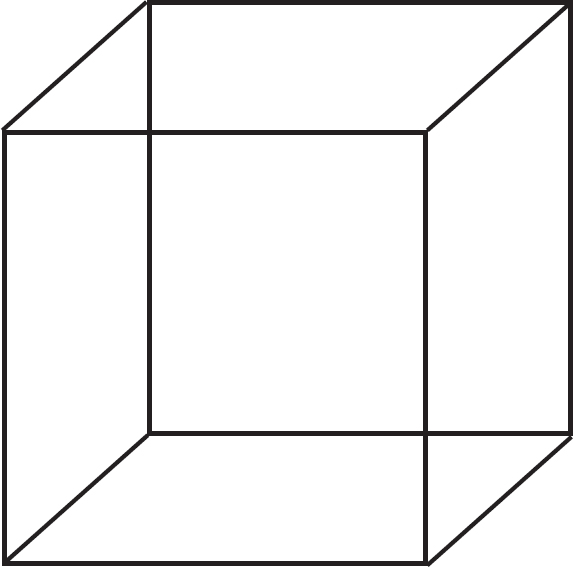

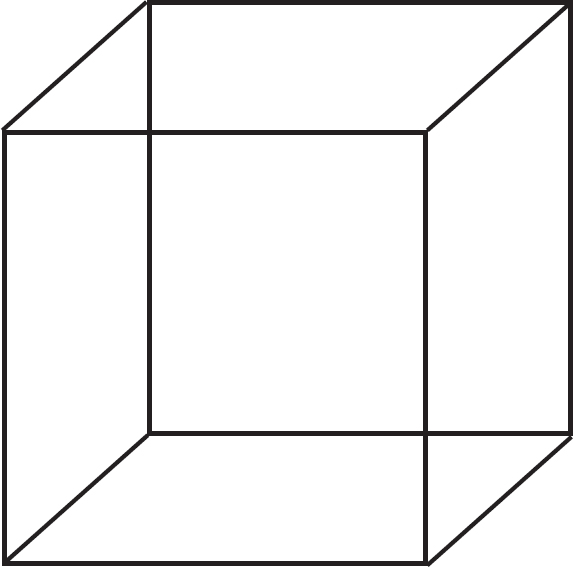

From moment to moment in rehearsals all sorts of things happen that are not apparent when I read the text over to myself. When someone is up on their feet saying the words, I hear new intonations because of an intuitive inflexion introduced by the actor, and I point it out. This is where the analytic function of the director begins, and there is a kind of vigilant inactivity on the part of a good director by which he or she lets the rehearsals go on and simply records intonations as they occur from day to day. By gradually picking out and reintroducing often unconscious deliveries given by a particular actor, the rehearsal develops. This reminds me of an ambiguous pictorial figure where, by developing and shading in the interpretation that favours one particular configuration rather than another, a new image begins to emerge from the old format. As the other alternatives are minimized, the perspective alters, giving prominence to the one interpretation that gradually becomes visible. It is like the Necker cube (below): a skeletal outline of a cube in which no face is obviously nearer or farther than another so that the front and back faces appear to alternate, and perception tends to oscillate unstably between the two alternatives. It is up to the director to point out the alternatives in the text, and to observe which one is emerging in rehearsal. By providing the actors with extra information, one interpretation can be solidified and the visibility of the alternatives diminished.

I used to start off rehearsals with a formal reading, simply because I submitted to the tradition that you sat around on day one and read the play through from beginning to end. I have abandoned this approach because it exposes the cast to unnecessary risks of embarrassment and humiliation, which arise inevitably when one actor appears at the outset to have a more definitive reading than the others. This confidence may not be a good thing if it means that those who are still stumbling and finding their way are put off or paralyzed on the first day. Now I tend to split the reading into small sections and, with two or three actors, read scenes that are not necessarily at the start of the play. Often the most productive implications about a character emerge when you begin with scenes halfway through the play, as though you have dropped rather casually into the middle of an event. The ideas that develop as a result of that reading may extend backwards into the, as yet, unread beginning of the play. In other words, I am increasingly tempted to allow the play to develop gradually, so that from little buds or islands the ideas grow out as if from quite separate centres and eventually meet to form a continent of meanings which comprise the contours of the whole work.

At the start of rehearsal, the play has an existence rather like an objective continent that is waiting to be discovered, and it is terribly hard to decide where to start to put the boats ashore. I am less and less tempted to start with a frontal attack on a play because it is so daunting, and can defeat the imagination of everyone concerned. In a way, the problem is very similar to the one that philosophers such as Wittgenstein have raised. It was he who said, and here I paraphrase, that you get mental cramps if you attempt a frontal assault on a large philosophical question like the meaning of meaning. But if you can first tackle a smaller, manageable question, and ask ‘What sort of meanings are there?’ and ‘What are the uses we put a particular word to?’ then we become familiar with the fact that meaning is a cluster of concepts rather than one concept that can be penetrated. In the same way, the play seems to be a cluster of characters whose nature will be discovered by attempting an assault on some element that may, at first, seem to be peripheral to its larger meaning. Gradually, by allowing one or two actors the experience of inhabiting the lines from inside, the daunting, objective entirety of the work is broken down.

In an intelligent, well-conducted and convivial rehearsal the cast is improvising by simply acting a scene in a way that allows you to see that its outcome is not yet determined. Improvisation in itself does not benefit rehearsal. I cannot see how improvising in a vacuum can possibly increase our knowledge of the play, as we are still confronted with the problem of how to tackle and approach the script. In rehearsal, the unforeseen and unforeseeable implications of a scene will sometimes emerge as a result of solving an incidental, technical problem that seemed quite trivial at the time. For example, in the fourth act of Chekhov’s Three Sisters there is a beguiling moment of bathos when Masha’s cuckolded husband, Koolyghin, tries to console her grief at the forthcoming departure of her lover, Vershinin, by suddenly appearing in a woolly beard confiscated from one of his pupils. The actor playing Koolyghin wanted to know when he should take the beard off, and I found it difficult to say when exactly. ‘Keep it on for a moment,’ I told him, having nothing better in mind at that time. ‘Brazen it out and we’ll see what happens.’ So, for a moment, he continued to wear the beard, not in his role as Koolyghin but as an actor who could think of nowhere else to put it. As we went on rehearsing, the prop reinstated itself as a feature in the play, and the actress playing Masha – in her role as Masha – suddenly took note of this woolly concealment, and, at the moment when she said it’s time to go, she walked across to her husband and unhooked the beard from his ears, only to discover, beneath its absurdity, the serious concerned face of her hitherto neglected spouse.303 It was as if by concealing himself under a deliberately assumed absurdity, he could reappear transfigured. In some mysterious way, the actor had gone into the beard as an insensitive clown and, because Masha had taken it off him, he emerged from its disguise appearing before her eyes as a man of dignity, kindness and patience. But all this happened as a result of solving an apparently trivial problem of when to take off a false beard.304

Another moment in rehearsal: Olga and Vershinin are standing together in the garden, studiously avoiding any reference to the dreadful moment when Masha will enter to bid Vershinin farewell. Janet Suzman had dreaded this moment almost as much as the character she was playing, and told me before we began rehearsing the scene that she would like to avoid the cliché of racing in distractedly. How to come in then? I suggested that the entrance might solve itself if she considered not so much her grief at his departure, or the distraction which that might provoke, but the embarrassment of farewells in general. She arrived, therefore, at the downstage corner of the scene, suddenly reluctant to draw attention to her own presence: wishing to be found, wishing to imply ‘I know you care less about our parting than I do so I won’t throw myself at you, and burden you with my insufferable misery. All the same, you should be able to tell by the abject self-effacement of my stance that I am grieving and that the rest is up to you.’ Alternatively, it is as if Masha anticipates that there is no written script for farewells under these circumstances. No more than there is for Vershinin who dreads the farewell for reasons that are complementary to Masha’s. As far as he is concerned another brief affair is over and presumably he would like to bring it to a conclusion as rapidly as possible. How tiresome if this were to involve a scene. Paradoxically, the effect of working all this through exerted a retrospective influence on the acting of the earlier relationship between the two of them. It was only by discovering the disparity of their emotions at the end of the relationship that we were able to go back to the beginning and discover aspects that had remained hidden when they were rehearsed in the chronological order of their occurrence in the play. In this respect, rehearsing a play is like constructing a novel, and in taking the events out of sequence the cast can enjoy the luxuries of analeptic conjecture.

I began by saying that as a director I do not have a secret method for rehearsals, but there is one strategy I find very useful, although it might be more aptly described as an abstention from strategy. Often, when an action or speech seems difficult or puzzling to an actor, the only way to resolve how it should be performed is to encourage him to find a way while pretending that you are not doing that at all. Let me give an example. At the end of a hard afternoon’s work, when nothing seems to have happened, I will call the rehearsal to an end and then suggest that we simply run over the lines to help memory. A couple of us will then go and sit down in the stalls, with or without the books, and feed each other cues. By this inadvertent method you make discoveries, and glean meanings and intonations, rather than deliberately harvest them in performance. This process is analogous to the one I saw in a patient with Parkinson’s disease, who very often found it difficult to make a deliberate assault on a task that he knew was hard for him to accomplish, but he could manage it if he pretended to do something else and literally caught himself unawares.305 Sometimes you have to creep up on your intention by pretending to be unintentional. Polonius’ words describe this circuitous approach:

And thus do we of wisdom and of reach,

With windlasses and with assays of bias,

By indirections find directions out

(II.i.61–63)306

In the process of rehearsal, it is often by the artful creation of apparent distractions that we discover direction. But it needs the vigilant attention of a director who, at the same time, pretends not to be looking out for such signs. At the end of rehearsal he must somehow resist the temptation to say: ‘I wonder if you realize that you came up with some very interesting stuff then?’ because the cast will then recognize this indirection for what it is. Perhaps three days later I might say, ‘Incidentally, why don’t you try it like that?’ knowing perfectly well that the actor has already done so – whether he remembers it explicitly or not – as the little read-through will have made him familiar with a new intonation or delivery.

As I have grown older, and I hope more mature, I leave more and more of the discoveries to be made by the actors themselves. In a sense I am doing what so many actors criticize directors for not doing, as I leave it to the imaginative talent of the performers to make the discoveries, in the only way that really interesting discoveries are to be made in texts, by inhabiting the lines subjectively and not by looking at them from the outside.

Now, this may sound as if, with time, I have abdicated all interpretative responsibility, but the very reverse is the case. Despite the fact that I am confined to an objective relationship with the text, I do have very useful ideas, but these take effect only if I keep on handing out little fragmentary insights – like tiny pieces of mosaic – which I leave to the actors to realize in the performance. If the director’s initiative were removed altogether, my role would be diminished to a consultative one and actors would come together, as they have done in the past, and form companies. The director would then be reduced to benevolently hovering over a bookshelf, checking the actors’ queries, and knowing which shelf to go to in order to look up what Tudor underpants were like.

In contrast to this fact-finder of a director, I think it is essential that the director feels provoked by the text rather than responsible for it. I hope that when this happens I do not react eccentrically, or see things that it would be perverse to say existed in the text. I like to provide the cast with a series of very approximate frames in which we can work. I am articulate but not, as it is often assumed, a terrifyingly intellectual director who daunts the cast. In fact, most of the people who have worked with me are struck by my permissiveness, in that my advice and recommendations are not dictations with regard to large-scale portraiture but little suggestions of gesture and nuance which, if acknowledged and possessed, the actors will find have implications beyond the play in question. The aim is that, without having to be further prompted, the cast will then continue to generate more performances that are consistent with these suggestions. The director is, in short, the creator of intuitive insights at moments where rehearsal might otherwise grind to a halt.

Complementary to the suggestion that only in the process of subjectively living the lines in performance will their full range of possible meanings come to light, there are certain aspects of the lines that can be brought to life only by some outside, objective judgement as to how the words sound when they are spoken in a particular way. The coexistence of the two – objective and subjective – is essential to the progress of the work as a whole. The lines must be lived actively and subjectively by the only person who is privileged to speak them – the actor – but, on the other hand, some of their meanings and implications are apparent only to someone who stands outside, and who will never enjoy the privilege of speaking them: the director. After all, this is what happens in our ordinary life. A person may speak the lines of their life without quite knowing what it is he or she means by them. Friends and bystanders are often in a better position to see what is meant than the person who is speaking to them.

In some ways the relationship of a director to an actor is, or should be, comparable to the relationship of any instructor to a learner. Obviously, learners can acquire a complex motor skill, like riding a bicycle, only if they take the risk of trying initially without adequate skill, and endure the possible humiliation and danger of falling before they succeed. A director can give broad instructions but cannot ensure success. Ultimately what must happen is that, like the child who has to taste the improbable experience of sitting upright on a machine whose base is not very easy to balance, the actor has to take a chance. In the end, no amount of explicit instruction will result in someone riding a bicycle. But discovering how to perform a play is much more complicated than riding a bicycle, and I think that most actors would bear witness to the fact that a friendly, accommodating and tactful adviser is a useful presence.

As with learning a motor skill, there is an element of mystery. I often find that the skill is not acquired during the learning session and, when the day ends, both teacher and learner – or actor and director – go home tired and depressed by their failure to bring any skill to light. Then a day passes in which there is no rehearsal, no practice of any sort, and on their return the actors enter into the text and speak it like angels. So too a child, after a miserable day of falling off the bike in the park, despite instruction and encouragement, may find three days later that he or she simply rides off. How this happens I can only conjecture, but it is as if, in that interim without practice, all the results of practice are rehearsed in some internal representation. This mysterious process might be compared to a computer simulation based on all the information that has been garnered during the apparently futile practice period. The information has been fed into the database and, without having to go through the tiresome procedure of enactment, a simulated, diagrammatic practice is performed by the machine internally. When we then encounter the real apparatus it is as if the computer simulation has eliminated all the boshed shots, and nine-tenths of the work has been realized and become very familiar.

There is a great deal of sentimental dogma about the length of time necessary for rehearsal to allow the possibility of some kind of strange alchemy to take place. It can simply become self-indulgent, and an opportunity for all sorts of silliness. Rehearsal is rather like painting: you sketch things in rapidly, and can soon see what is acceptable. Then the director can erase and adjust in much the same way as an artist. My usual rehearsal period is four to five weeks. It becomes very boring if it stretches to six weeks. People could argue that this is because I have pre-empted the alternatives too early, and not allowed the play to be productively unstable for long enough. I can only say that I have never regretted any decision reached early on in rehearsal, and have often sent actors home after four or five weeks to rest for a couple of days rather than drag on with unnecessary rehearsal.