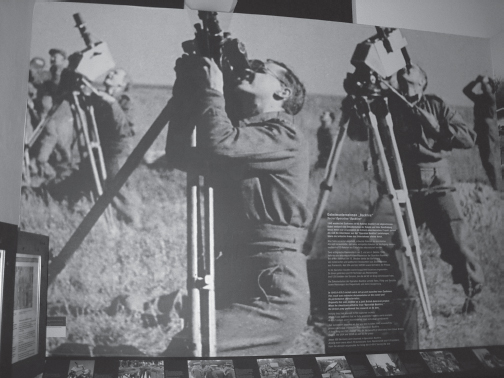

A British soldier inspects a V2 and its Mielerwagen transporter/erector at a typical forest launch site somewhere in Holland. (Medmenham Collection)

Forward thinkers, particularly among the three great Second World War Allies, the Americans, Russians and British, undeniably impressed by the German innovation which resulted in the Vergeltungswaffen, were now anxious to lay their hands on their definitive designs, hardware and expertise – and the Russians were the first to do so when they occupied Blizna on 6 August 1944.

In a letter to Stalin, dated 13 July 1944, Churchill alerted the Russians to the importance of the missile testing range at Blizna when he sought his permission for a group of British specialists to visit the area once it had been occupied by Soviet troops. Stalin agreed but, having been so alerted, he ordered Major General P.I. Fedorov, director of NII-1 (Russian Research Institute) to pre-empt the British visit by taking his own team to scour the area in early August, and remove anything which might be of value to their own research. In fact, it was soldiers of General Kurochkin’s Sixtieth Soviet Army who recovered the first pieces of the V2 found there in the second week of August, before the NII-1 team arrived. At that time the Russians had little knowledge of rocket technology nor any idea what they were looking for because when the British arrived, armed with maps of the launch areas and other points of interest on the range, together with details of the missiles, they found many useful remnants to take back to London for evaluation.

At the end of the war, the Soviets were in control of 600 German aircraft plants, or 50 per cent of the total capacity, but they wanted more as reparations for the damage the Germans had done to their country. Clearly the defeated country could not pay the millions of dollars demanded, so Joseph Stalin set up a ‘Trophy Committee’, consisting of representatives of Soviet industries, tasked with seeking out and securing anything of potential scientific or technological value and shipping them back to Russia, as their armies marched into Germany, rocket science being high on their list of priorities.

The next source of interest was Peenemünde where the Germans had stripped down every facility and strived to destroy anything of value on missile hardware and documents, but the Russian NII-1 specialists still found much of interest when they arrived there on 2 May 1945. They discovered large items from various Aggregate rockets, launching platforms and a complete Rheinbote rocket gun, in addition to many documents on other projects, including a revolutionary rocket-propelled aircraft which undoubtedly helped the Russians with this new science. Most of the German scientists and senior specialists had already fled south but the Russians did capture Helmut Gröttrup, one of von Braun’s chief assistants and initially 200 of Gröttrup’s colleagues, from which nucleus grew a body of some 5,000 workers from all skill levels which was put to work repairing and salvaging what they could to return Peenemünde to a productive unit – albeit as a shadow of its former self. What might have seemed like a good deal to the Germans, for them to have a job at all in their war-torn country, let alone one with which many of them were already acquainted, came to an abrupt end a year later. On 22 October 1946 Stalin ordered Operation OSOAVIAKHIM, the removal and dispersal of the whole facility and many of the workers, ostensibly on five-year contracts, to separate sites in Russia, where work would continue on weapons development. Gröttrup himself was working under the eminent Russian rocket engineer Sergei Korolev in NII-88 on Gorodomiya Island. At the same time some Russian scientists were sent to Germany to study at appropriate academic institutions, while back-engineering and a new fuel produced a successful Russian version of the A4 (V2), the R-11; this rocket, which emerged in 1955, had a range of 170 statute miles. The German workforce, effectively kidnapped in 1946, would remain in Russia for several years, helping to breathe new life into Russian advanced weapons technology, until they were no longer needed when they were returned to Germany.

A British soldier inspects a V2 and its Mielerwagen transporter/erector at a typical forest launch site somewhere in Holland. (Medmenham Collection)

American troops discovered ‘ready to use’ V2s on railway wagons close to the Mittelwerk production centre. (Medmenham Collection)

It was, however, the Americans who won the ‘jewel in the crown’ of Germany’s missile legacy when they arrived at Nordhausen and its massive weapons factory, underground at Mittelwerk, on the southern edge of the Harz mountains. This prize fell to Combat Command B (CCB) of 3rd Armored Division, US Army, which discovered the horrors within the tunnels of Mittelwerk and at Camp Dora but also a treasure trove of complete missiles, missile components and ancillary equipment, much of it loaded on freight trains ready to leave for the front. Wasting no time the US Chief of Army Ordnance Technical Intelligence in Paris, Colonel Holgar Toftoy, sent teams of experts to Mittelwerk to raid the offices and workshops for every technical detail on the two missiles, and initiated ‘Special Mission V2’, the evacuation of 100 V2s and associated equipment to the USA.

With commendable dispatch, and paying little heed to an earlier agreement that any such find would be split equally between the Americans and British, the first forty of 341 fully loaded railway wagons left Mittelwerk for Antwerp docks on 22 May, the last leaving on 31 May. Within days, the first of sixteen Liberty ships left Antwerp for New Orleans, to be trucked on to White Sands Proving Ground, New Mexico. The CCB may have been unaware then that Mittelwerk would be in the Soviet zone of occupation because a residue of missile equipment remained there for the Russians to find when they arrived on 21 June.

There remained the need for experienced German missilemen to clarify the technical details needed to avoid the problems found during the testing, trials and launching of the missiles at Peenemünde, Blizna and elsewhere, and in helping to ‘reverse-engineer’ the missiles, and it was down to Major Robert Staver of the US Ordnance Office to find this expertise. The big fish, including von Braun, had by this time surrendered to the Americans in the lower Baverian Alps, and were under guard in Garmisch Partenkirchen where selection for employment on rocket work in America was taking place. However, back at Nordhausen, Staver found V2 engineer Otto Fleisher and structural engineer Walther Riedel who were only too pleased to help, again with the prospect of emigration to the United States. A further search of the area revealed another pool of expertise, covering most aspects of missile technology, from which von Braun’s engineers identified the men they thought would be of most use to the Allies and, on 20 June 1945, the best of these were moved a few miles south-west, to Witzenhausen, in the US Zone, one day before the Russian occupation of Nordhausen. Angered that the Americans had taken the best of the missile bounty, and having failed to woo more than a handful of potentially useful German scientists and technicians into their employ, the Russians hatched a plan to kidnap some or all of those now lodged temporarily at Witzenhausen. They entered the town with convincing paperwork and dressed in British military uniforms (believing they were in the British Zone) but the American guards were smart enough to detect the ruse and sent them on their way.

There only remained that huge cache of documentation on the Vergeltungswaffen, so scrupulously recorded in the German way and hidden by Dieter Hexel in the old mine at Dörnten, to give the Americans all they wanted to pursue rocket technology in the their own backyard (Chapter Ten). Again Staver came to the rescue when he found one of the few remaining missilemen at Nordhausen, Karl Fleisher, who knew where the documents were hidden and, on 20 May 1945, he led the Americans to them.

The Americans may have secured the lion’s share of the rich pickings to be had at Mittelwerk, but a Soviet ‘Special Purpose Brigade’ still managed to find some items of interest which were assembled in Berka, near Zonderhausen, run by Major General Tveretsky and veterans of the Russian Katyusha (Rocket) units. Further missile ‘trophies’ found in Bad Sachsa, a stopping-off place for the Peenemünde party heading south, were said to have been shared with the Americans. Meanwhile, a key member of NII-1, Boris Chertok, who was already making use of the missile expertise of German specialists found languishing in Russian prison camps, arrived at Nordhausen as late as July 1946 and still managed to make contact with, and recruit, the few German missile technicians still there. Finally, the Russians also lured a few more of the German rocketeers from the care of the Americans in Bavaria with better pay and food, and the chance to stay in Germany, but all these efforts paled into insignificance compared with the Americans’ rich pickings.

The British, having been outwitted by the Americans on the ’50:50 per cent’ deal, did their best to make up ground with a Special Projectile Operations Group (SPOG). While they already knew much about the rocket from the errant V2 which had crashed in Sweden and from good intelligence work by Polish and Dutch partisans (Chapter Four), they needed to know more, particularly on the operational missiles’ support equipment. This being so, and with so many rocket scientists and 8,000 German rocket troops now in Allied hands to help them, the British secured permission from Supreme Commander Eisenhower to ‘to ascertain the technique for launching long-range rockets, and to prove it by actual launches’. SPOG was tasked with demonstrating the preparations for – and firing of – three fully serviceable V2s into the North Sea, monitored by radar, from a well-equipped German naval gun range at Altenwalde, south of Cuxhaven. The War Office was given ultimate responsibility for Operation BACKFIRE, with Major General Cameron in command and Colonel W.S. Carter running the demonstration; the Americans would provide support and the exercise would be witnessed by a selected audience from the Allied Powers. Wernher von Braun and Gen Dornberger were released from American custody, temporarily, to advise the British, particularly on matters of safety and security, propellant storage, transport, loading, erection and best firing sites, Dornberger offering thirty of his men to help with the tests. The rocket troops assisting in the exercise who formed into the Altenwalde Versuchskommando (AVKO), a military style unit under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Weber, one-time commander of the very successful Training and Experimental Battery 444, included everyone, civilian and military, involved in the final preparations – and the launches themselves; all had significant operational experience with V2s in the field and would add logistical support. For the purpose of the exercise, and for some rocket work thereafter, some who were already in US custody were lent to the British. Other prominent Germans who contributed to BACKFIRE were Kurt Debus, who had been responsible for Peenemünde’s Test Stand VII, Hans Fichtner and Al Zeiler, while British rocket specialists would be on hand to witness the preparatory work and the firings. Two thousand Canadian engineers, supplemented by a force of British soldiers, took three weeks to refurbish existing facilities and build special equipment for the trials, which included a giant proofing tower, a vertical structure for testing the rockets in their launch position, constructed from parts of a redundant Bailey bridge. The majority of the rocket technicians and their assistants arrived at Altenwalde on 22 July where they were split into two groups and interrogated, a final group joining them in the second week of August.

British, American and French officers witness the live firing of a V2 from the Cuxhaven Weapons Range during the British Operation BACKFIRE, in September 1945, many German specialists on the weapon assisting on site. (Author, Courtesy HTM Peenemünde)

British weapons specialists trace the launch of a V2 during Operation BACKFIRE. (Author, Courtesy HTM Peenemünde)

Initially, there was some concern that the Germans intended to assist in the British trials might not be welcomed by those who had been on the receiving end of the V2 attacks but this proved to be ill-founded. Likewise, those Germans who were already in US custody in Bavaria, and who had been hoping for free passage to a new life in America, were very reluctant to be drafted to support BACKFIRE. However, they were somewhat consoled by the treatment they received from the British, additional pay, special rations, normal working hours in their specialisation, often with old friends, while enjoying recreational activities and plenty of freedom to roam in the local area.

From the eight V2s available, (some of these had been secreted away from Nordhausen by the British before the Americans arrived, others were found in railway wagons abandoned in Jerxheim and Lesse, North Germany) five were prepared for the trials. Long and intensive searches gradually revealed the necessary support equipment, found hidden away in the British zone of occupation around Celle, Fallingbostel and Lisse, much of it needing repair and refurbishment. Again, after much searching, a factory at Fassburg was re-opened to produce liquid oxygen, 70 tons of ethyl-alcohol was found on a train near Nordhausen and a stock of hydrogen-peroxide was found in Kiel. By mid-August the British had assembled and organised all the elements required for the two phases of BACKFIRE. Phase One dealt with the assembly of the rockets and all the ancillary equipment, Phase Two the final preparations, launches and behaviour of the rockets in flight. The German support was divided into two groups; the AVKO in Camp A, while a separate entity comprising twenty of von Braun’s senior civilian staff made responsible for recording every aspect of the trials were lodged in Camp C. In addition to the Canadian contingent, some 150 scientists, 100 rocket troops and a working party of 600 PoWs were involved, and all was set for the trials to begin by the middle of September 1945.

The first launch, scheduled for 27 September 1945, was postponed because of bad weather and on 1 October two more attempts failed, due to ignition faults. However, at 14.41 on a bright and clear 2 October, everything worked perfectly, bringing plaudits all round; the rocket reached a height of 23, 000 feet and a distance of 154 miles. Just after the second launch, on 4 October, the engine failed but, on 15 October, a third launch at 15.06, before a large number of British, American, Russian and French spectators, was successful, climbing to 21,000 feet and landing, as planned, 144 miles down the range.

Despite the small number of launches, Operation BACKFIRE was considered to have been a great success – and very well worthwhile in the context of future research into stratospheric, supersonic rocketry. The evaluation had proved more difficult to stage than had been anticipated, inter alia heaping great credit upon the Wehrmacht’s rocket troops who had once contributed their best under threat from the air at all times in the field, during the confusion and turbulence of war, and had now done so again in the relatively benign environment of peace.

Following the operation those of von Braun’s team of specialists who had been detached from Bavaria were returned there, to be accommodated at a disused Wehrmacht barracks at Landshut, known as Camp Overcast, the British having failed to persuade the Americans to let them keep some of the rocketeers for their own purposes. At Camp Overcast, 150 of the scientists and technicians were offered five-year contracts to work for the US Army in the USA, their families looked after at Camp Overcast until arrangements could be made for them to be accommodated in America. This was the beginning of Operation OVERCAST, later Operation PAPERCLIP, in which a chosen few were moved to the Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, via New York, in September 1945, while others from Peenemünde were given employment, initially at Fort Bliss, Texas, pending a more permanent home for all the Germans at White Sands, New Mexico, where, in April 1946, the first of some sixty V2s taken from Mittelwald, re-christened ‘Bumper’ was launched. Many rockets based on V2 technology followed, in many different configurations. The Americans had rich pickings and they did not delay putting their new acquisitions to work.

Although the British had failed to recruit some of German rocket scientists they wanted, they did get the service of others, employing them at the Royal Aircraft Establishments at Westcott and Farnborough where they made significant contributions out of all proportion to their numbers. The V2s they had acquired also provided the model for a British-designed equivalent, which incorporated a small cabin for training an astronaut – but nothing came of it.