‘The price of eternal vigilance is indifference.’

– Marshall McLuhan

In his too-hasty indictment of the 1999 NATO air campaign over Kosovo,

Strategy of Deception, Paul Virilio suggests that there was a determined relation between the ‘humanitarian’ dimension of this very first ‘human rights conflict’ and the ‘truly panoptical vision’ which NATO brought to bear on the battlefield (2000: 19–21).

1

After the eye of God pursuing Cain all the way into the tomb, we now have the eye of Humanity skimming over the oceans and continents in search of criminals. One gets an idea, then, of the ethical dimension of the Global Information Dominance programme, the attributes of which are indeed those of the divine, opening up the possibility of ethical cleansings, capable of usefully replacing the ethnic cleansing of undesirable or supernumerary populations. After oral informing, rumor, agents of influence and traditional spying, comes the age of optical informing: this ‘real time’ of a large-scale optical panoptic, capable of monitoring not just enemy, but friendly, movements thanks to the control of public opinion. (2000: 21–2)

This ‘global tele-surveillance’ (2000: 22) is for Virilio the signature of the ‘globalist putsch’ he denounces, ‘a seizure of power by an a-national armed group (NATO), evading the political control of the democratic nations (the UN), evading the prudence of their diplomacy and their specific jurisdictions’ (2000: 74).

Fig. 1 Border station near Globocica, Kosovo, April 1999; image from Bundeswehr CL 289 UAV (drone). Source: Bundeswehr.

Fig. 2 Bodies at Racak, Kosovo, January 16, 1999; news photograph from Koha Ditore (Pristina). Source: Koha Ditore.

The tropes are all-too-familiar, and not just to readers of Virilio. Democracy sacrificed to speed, accountability to total visibility. As if surveillance were just one thing. As if the images produced by the global panoptic were self-evident in their meaning or effect. And as if every project taken on by the Western military alliance, or what his [French] Foreign Minister Vedrine memorably nicknamed the hyper-power, was irremediably contaminated. But those are obvious commonplaces. What is interesting is the question of betrayal, denunciation, of this ‘informing [délation]’. What difference does all the watching make? Especially where ‘ethnic cleansing’ is at stake – or to call it by its legal name, where genocide is underway? Virilio’s dissident position, that what is truly to be feared and resisted is less the killing itself than the practices of global control it alibis or sets in motion, is at once unjustified and deeply flawed from a political standpoint.

But, interestingly, it also runs counter to the most cherished axioms of the international human rights and humanitarian movements. Since the end of World War II, indeed, the non-governmental movement has looked forward to the prospect of up-to-date information about crimes in progress, coupled with access to the public opinion that might enable them to be interrupted. With the creation of a rich and increasingly robust global network of human rights monitors, and the ability to relay acts of witness and evidence around the world in near real time, something like this transparent world is increasingly real. ‘The media will carry the demand for action to the world’s leaders; they in turn must decide carefully and positively what that action is to be’, runs the axiom in its clearest formulation.

2 But what of the reaction, the action, and the public? Kosovo – where a limited military intervention probably prevented a genocide, protected a terribly endangered civilian population, and finally stopped a military and paramilitary apparatus that had terrorised primarily Muslim civilian populations in Southern Europe for most of the 1990s – was rather the exception than the rule. Global tele-surveillance and human rights monitors did not help much at Vukovar, Omarska or Srebrenica. Nor did these names confirm the omnipotence of NATO, or the unaccountable power of the transnational human rights movement. After a decade of genocide, famine and concentration camps, the very value of publicity – whether that affirmed by the movements or condemned by Virilio – seemed questionable.

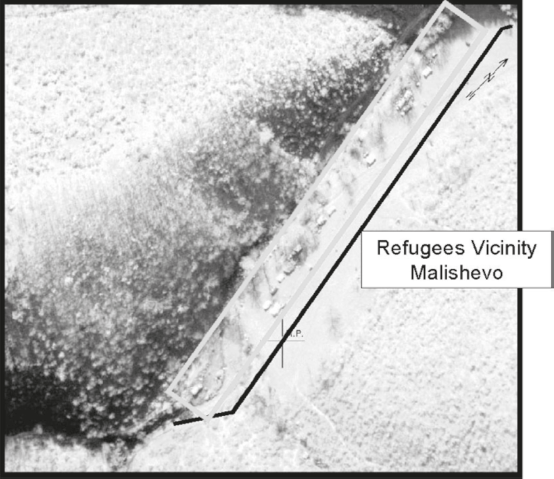

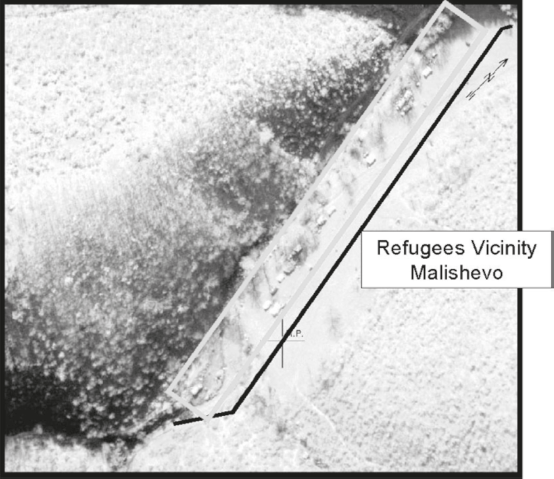

Fig. 3 Refugees, vicinity of Malisevo, Kosovo, April 1999; overhead imagery released at NATO briefing, April 10, 1999. Source: NATO.

Visiting Sarajevo at Christmas in 1993, less than a year into its suffering, the Archbishop of Paris Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger noted the strikingly public or visible character of the carnage there.

3 In an interview with Zlatko Dizdarevic of Sarajevo’s

Oslobodjenje, he compared the siege of the city to the horrors of World War II, but with a significant difference:

Here, however, there are no secrets. There are journalists here, from here pictures are transmitted, there are satellite communications, all of this is known. In this city there are soldiers of the United Nations, well armed, and nonetheless it all continues to happen. This is unbelievable; this is overwhelming. One man yesterday told me that everyone here feels like they are animals in a zoo that others come to look at, to take pictures of, and to be amazed. And then, those up in the mountains also treat them like animals, killing them and ‘culling’ them.

Dizdarevic asked how it was possible that, ‘all of this goes on without any end in sight, in spite of the fact that we are surrounded by hundreds of cameras [and] that everyone knows everything and sees everything?’ Lustiger responded: ‘There is no answer for that – I really do not have an answer. However, that means that it is always possible to get worse and worse.’

Lustiger’s bold and uncompromising position, as rare as it was at the time, has now achieved the status of common sense. Among the too many would-be ‘lessons of Bosnia’, this one stands out for its frequent citation: that a country was destroyed and a genocide happened, in the heart of Europe, on television, and what is known as the world or the West simply looked on and did nothing. ‘While America Watched’, as the title of a documentary on the genocide in Bosnia broadcast by ABC Television in 1994 already put it.

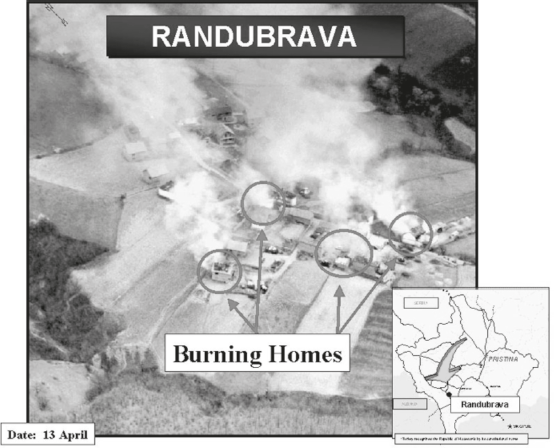

4Fig. 4 Burning homes in Randubrava, Kosovo, April 13, 1999; overhead imagery released at NATO briefing, April 14, 1999. Source: NATO.

The surveillance was as complete as the abandonment. Bosnians, said one to the American journalist David Rieff, ‘felt as you would feel if you were mugged in full view of a policeman and he did nothing to rescue you.’

5 Or, as Rieff himself put it:

200,000 Bosnian Muslims died, in full view of the world’s television cameras, and more than two million other people were forcibly displaced. A state formally recognized by the European Community and the United States […] and the United Nations […] was allowed to be destroyed. While it was being destroyed, UN military forces and officials looked on, offering ‘humanitarian’ assistance and protesting […] that there was no will in the international community to do anything more. (1996: 23)

But what does ‘in full view’ mean, and what is the particular ethico-political force of this condemnation: not just genocide, but genocide in the open, transparent mass murder?

There is no denying the simultaneity of this watching and that destruction. They happened together – and what happened should not have happened. But what did the surveillance and the watching have to do with what happened? What links the thing we so loosely call ‘the media’ and its images with action or inaction? Or more precisely, when something happens ‘in full view’, why do we expect that action will be taken commensurate with what (we have seen) is happening? And what about that humanitarian assistance: what sort of ‘action’ is it?

This trajectory of this programme – from the camera to a response, but maybe nothing ‘more’ than a humanitarian one – appears everywhere today, in military and political and historical discussions of so-called postmodern wars or humanitarian crises, in legal or ethical commentaries on genocide and catastrophe, and in critical media-studies analyses of what has been called ‘the CNN effect’ or the-role-of-the-media in contemporary conflict. And what seems to concern us most, for better and for worse, are the media. It seems as if we cannot talk about what happened in Bosnia or Somalia or Rwanda without talking about the media.

6Consider, for (and unfortunately only for) example, the brilliant series of articles in the

New York Review of Books in which Mark Danner chronicled the high and low points of the battles over Bosnia in the United States and Europe. He was in Sarajevo for much of it, but his articles insistently begin with watching television.

7 ‘To the hundreds of millions who first beheld them on their television screens that August day in 1992, the faces staring out from behind barbed wire seemed painfully familiar’, begins his 4 December 1997 report on the camps of Western Bosnia. The opening sentences of his 20 November article tell a similar story about Srebrenica:

Scarcely two years ago, during the sweltering days of July 1995, any citizen of our civilized land could have pressed a button on a remote control and idly gazed, for an instant or an hour, into the jaws of a contemporary Hell. Taking shape upon the little screen, in that concurrent universe dubbed ‘real time’, was a motley, seemingly endless caravan, bus after battered bus rolling to a stop and disgorging scores of exhausted, disheveled people […] every last one a woman or a child. The men of Srebrenica had somehow disappeared. Videotaped images, though, persist: on the footage shot the day before, the men can be seen among the roiling mob, together with their women and children, pushing up against the fence of the United Nations compound, pleading for protection from the conquering Serbs. (1997: 55)

From 1992 to 1995, says Danner, we watched, and what we did and didn’t do with what we saw was all the less forgivable, because we could see.

8 Many other versions of this protest could be enumerated, but the precise formulations of and differences among them are less interesting than their ubiquity. The recurrence of the gesture (we watched ‘all that’ but we did not act as we should have), across so many different accounts and styles and methodological predispositions, mirrors somehow the phenomenon it describes: the omnipresence of the gesture is the very ubiquity of the camera, the image or spectre of the camera that now seems to haunt our consciousness, and indeed, the in-full-view-of-the-camera seems now to have become the most privileged figure of our ethical consciousness, our conscience, our responsibility itself.

This was not always a rebuke. Television, publicity, surveillance of the affirmative sort, was supposed to help. This was the situation Michael Ignatieff described some years ago – before Bosnia and Rwanda, when the crises were those of starvation and Cold War proxies – in an essay on ‘the ethics of television’, now the first chapter of

The Warrior’s Honor.

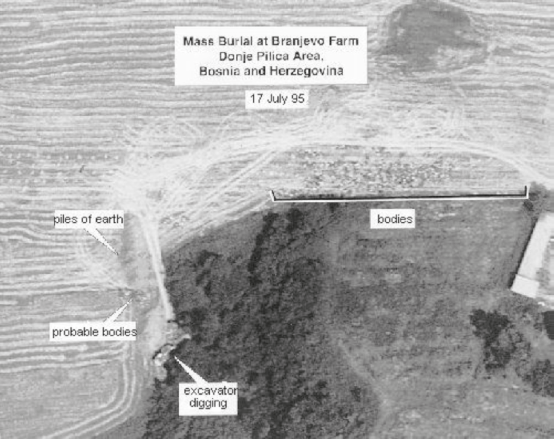

9Fig. 5 Mass burial at Branjevo Farm, Donje Pilica Area, Bosnia-Herzegovina, July 17, 1995; image from United States U-2 aerial reconnaissance aircraft, released by US officials in Bosnia, March 22, 1996. Source: US Department of State.

Television is also the instrument of a new kind of politics. Since 1945, affluence and idealism have made possible the emergence of a host of non-governmental private charities and pressure groups – Amnesty International, […] Medecins sans frontières, and others – that use television as a central part of their campaigns to mobilize conscience and money on behalf of endangered humans and their habitats around the world. It is a politics that takes the world rather than the nation as its political space and that takes the human species itself rather than specific citizenship, racial, religious, or ethnic groups as its object. […] Whether it wishes or not, television has become the principal mediation between the suffering of strangers and the consciences of those in the world’s few remaining zones of safety. […] It has become not merely the means through which we see each other, but the means by which we shoulder each other’s fate. (1997: 21, 33)

Fig. 6 General Ratko Mladic, Bosnian Serb Army, Potocari, Bosnia- Herzegovina, July 12, 1995; video still of RTS image on CNN, date unknown. Source: Radio Television Serbia via CNN.

Ignatieff allows us to orient this enquiry toward the special relationship between television and humanitarianism. International humanitarian action of the sans-frontières variety is unthinkable except in the age of more-or-less instant information. As Rony Brauman has underlined, the founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1864 is linked non-coincidentally to the possibility of high-speed transmission by telegraph, and contemporary relief operations since Biafra and Ethiopia have been born and bathed in the light of the television camera and the speed of the satellite uplink.

10 Humanitarian action seems not simply to take advantage of the media, but indeed to depend on it, and on a fairly limited set of presuppositions about the link between knowledge and action, between public information or opinion and response. In some cases, like that of the international human rights movement, as Alex de Waal has argued, the conditions of action rest all too heavily on the concept of ‘mobilizing shame’.

11

In the humanitarian arena proper, the pioneering French activist turned politician Bernard Kouchner put the coordination between media and intervention in a simple epigram: ‘sans médias, pas d’action humanitaire importante, et celle-ci, en retour, nourrit les gazettes [without the media, there is no important humanitarian action, and this, in turn, feeds the papers].’ Kouchner calls this ‘la loi du tapage’, the law of noise.

12 And among military thinkers, practitioners, and diplomats, the sense that television imagery or news dispatches ‘drive’ decisions about intervention has by now gained a name of its own – ‘the CNN effect’ – and is the topic of vigorous debates.

13 (1997: 3–4)

Fig. 7 Somalia, September 1992; video still from CNN, date unknown. Source: CNN.

What does it mean? Thanks to what is loosely termed ‘public opinion’ in the media age, which displaces or warps of state institutions and power through emergent alternative centres of power like the media and non-governmental organisations, the so-called ‘famine movement’ (or what Alex de Waal has nicknamed the ‘Humanitarian International’) has emerged as a political actor, and of a new sort: apparently unlimited by traditional notions of sovereignty, accountability, borders, interest and the rest.

14We need to understand the ‘humanitarian action’ which triumphed in Bosnia as something different from either of the two obvious options: it was neither inaction (a passive acquiescence or a cover-up, a fig leaf that disguises the actual doing-of-nothing), nor a heroic new non-state politics of the sort anticipated by many of the founders of the movement. It was an action that – precisely because it offered the possibility of a reference not to national interest or the defense of the state but to what it called, alternatively, ‘human beings’, ‘victims’, ‘misfortune’ or ‘suffering’, and did so by way of public opinion and the image, which is to say by reference to the order of the ethical – opened the possibility of a political discourse that, for better or more often for worse, did not have to justify itself in political terms. In Bosnia, humanitarian action was action indeed, action that threatened to totalise the field of all possible action: not simply to hide inaction or offer alibis for not doing other things, but more radically to interrupt, to render impossible, to actively block or prevent those actions.

And this action had as its field or condition the image, sometimes precisely the image and sometimes more generally what we nickname ‘the media’ or ‘real time’. Recall that for Walter Benjamin, in the ‘Work of Art…’ essay at least, the invention of the motion picture introduced nothing less than a temporal explosion, ‘the dynamite of the tenth of a second’, such that in what remained, the ‘far-flung ruins and debris’ of our daily lives or our familiar terrain, would open up ‘an immense and unexpected field of action.’

15 Film and today television do not only collapse and annihilate, as is so often said, time and distance – they also make unprecedented times and spaces available for action, real virtualities that are marked by the affirmation of possibilities of engagement, ‘action’, as well as by the negativity of this ‘dynamite’. Field of action, yes, but what kind of action? The answer is also Benjaminian, though this time in a different way. The privileged example at the close of the ‘Work of Art…’ essay is war, what he labels the aesthetics of mechanised warfare, which he says is discerned more clearly or best ‘captured by camera and sound recording’ and not the naked eye (1969: 242, 251). Today cameras don’t simply represent conflicts but take part in them, shape not only our understanding of them, but their very conduct. We need to attend to these sounds and images not just as accounts of war but as actions and weapons in that war, as operations in the public field, which today constitutes an immense field of opportunity for doing battle, as weapons in what we too easily call ‘image contests’ or ‘publicity battles’.

‘There was a cameraman there’ – this is a fragment from a news report about a man shot by a sniper in Sarajevo:

16

Mr. Sabanovic got in the way at a particularly dangerous Sarajevo crossroads. That is why there was a cameraman there to film his near death. Because the spot is treacherous, the chances are good that a few hours of patience by a cameraman will be rewarded with compelling images of a life being extinguished or incapacitated. (Cohen 1995: 12)

What difference does it make that a cameraman is there, as he or she so often is? No matter where, it seems, a camera regularly happens to be there, when something happens to happen. So much so that it has become a cliché, a veritable commonplace, to say that today things don’t happen

unless a camera is there. Of course, it takes not just a camera, but an entire network of editing, transmitting, distributing and viewing technologies – and agents – that extend out from the camera, to make what Marshall McLuhan so famously and confusingly called a global village.

17 But it begins with the camera and its operator, with their already having been there.

What the journalist here wants us to understand is the complex structure of that ‘there’: was it a place where cameras waited patiently for things to happen (a particularly dangerous crossroads), or a place where things happened because cameras waited patiently (compelling images of lives extinguished)? The camera is there because of the danger, but its silent witness transforms the event and its ‘there’ – that is what matters here. Thanks to the camera, what it means for the event to occur, its taking-place, undergoes a mutation. The crossroads so precisely targeted in the sniper’s gun-sight is also the blurred intersection of what our impoverished theoretical vocabulary allows us to call only event and representation, occurrence and image. This confusion cannot be written off as one more version of a timeless ontological conundrum (which comes first?), nor caricatured as a postmodern prejudice for the discursive over the real, nor simply eliminated with a declaration of the moral superiority of the things themselves. The confusion itself is all too real and – especially in the case of events like those at this crossroads – it constitutes something like an exemplary ethico-political difficulty and opportunity for us.

What is at stake, finally, in this confusion is a certain experience and definition of public space and time, of publicity and of a crisis in our sense of public information and exposure today. The corollary, of course, of the cameraman’s being there is that, in some sense, we are too. The camera metaphorises the becoming-public of the event, because we who watch and listen are also caught in the intersection of the sniper’s and the cameraman’s viewfinders – not as potential victims exactly, but in some other sense as targets of those vectors (borrowing this sense of the word from McKenzie Wark in

Virtual Geography).

18 What do we do in watching and listening? When I say ‘we’, I mean that hazy thing called the public, a rich concept sent to us by the Enlightenment and the French Revolution and in need of extensive rethinking. If the public means us, us in our exposure to others, then today ‘we’ cannot be something given in advance, not the sum total of all of us somewhere or sometime, not a community or a people but rather something that comes after the image, a possibility of response to an open address. The public, we could say in shorthand, is what is hailed or addressed by messages that might not reach their destination. Thinking about the images at hand, we could even say that what makes something public is precisely the possibility of being a target and of being missed.

So the television image constitutes a field of action – not just a representation of actions elsewhere but a field in or on which actions occur – a public field, we could say, but only if we’re willing to part with some of the cherished predicates of that concept.

Somalia, December 1992. The first American soldiers of Operation Restore Hope land on an Indian Ocean beach at Mogadishu, met not by clan fighters or starving children but by hundreds of reporters, camera people, technicians, whom, as it turns out, the American military had informed in advance of the time and place of the operation. Kouchner’s claim that without television, there is no humanitarian intervention, seems to come true in a multiple and almost perverse way here: not simply that images – there, of starving children – could shame governments into action, but that armies will undertake humanitarian rescue missions for the publicity value alone, and that publicity could also bring the mission to an end.

What happened there? We are not finished understanding the complex of clan politics and paramilitary violence, the liquidation of the post-colonial and post Cold-War state, famine and even starvation, and the succession of interventions, humanitarian and armed ones, and then nation-building which followed them.

19 But the images (from the starving children to the gun-belted fighters, the brightly-lit landing, the camcorder pictures of a helicopter pilot held hostage and a dead soldier dragged in the street) and the phrases (Mad Max vehicles, warlords, the photo-op invasion and the CNN effect, and the Mogadishu line) have already decisively shaped the interpretation and practice of humanitarian interventions in the decade since that fateful night in the lights.

20The lesson of those lights was already clear, the morning after the event, to the grand old man of American foreign policy, George Kennan, who awoke that morning in December 1992 to watch the soldiers landing in real time, surrounded by reporters and interviewed on the beach, and offered a harsh assessment of the damage. He told his diary, and then the opinion page of the New York Times, that he had finally seen enough:

Fig. 8 Mogadishu airport, Somalia, December 9, 1992; live video still from NBC. Source: NBC.

Fig. 9 Mogadishu, Somalia, October 4, 1993; video still from CBS, October 4, 1993. Source: Reuters via CNN.

If American policy from here on out, particularly policy involving the use of our armed forces abroad, is to be controlled by popular emotional impulses, and particularly ones provoked by the commercial television industry, then there is no place – not only for myself, but for what have traditionally been regarded as the responsible deliberative organs of our government, in both executive and legislative branches.

21

Fig. 10 Mogadishu airport, Somalia, December 9, 1992; live video still from CNN. Source: CNN.

Kennan – the architect of the Cold War, the author of the doctrine of ‘containment’, Mr. X himself – watches his era end on his television, not with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Europe, nor with the great borderless coalition and its triumph in the Gulf War, but with chaos on an African beach, disaster breaking out of new world order with such energy and confusion that it threatens to tear apart the institutions of government and publicity themselves. What is threatened in Mogadishu, not by the clans but by the cameras and the soldiers who are drawn to them, is nothing less than the basic structures of ethics and American democracy – responsibility and deliberation. The rational consideration of information, with a view to grounding what one does in what one knows, now seems overtaken and displaced by ‘emotion’, and responses are now somehow ‘controlled’ or, better, remote-controlled by television images. What disappears beneath the image or behind the screen is the place of politics itself. There is, Kennan confesses, not only no place for him but no place at all for a decision, for the organs that regulate the link between knowledge and action. Television – that virtual place – displaces the public place, substituting emotion for reason, immediacy for the delay proper to thought.

Fig. 11 Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, January 1993; video still from CNN, January 26, 1993. Source: CNN.

In somewhat more complex, but no more theoretical, terms, Virilio has suggested that this phenomenon, the displacement of the traditional rational-critical experience of the public sphere by what is nicknamed ‘emotion’, characterises in general contemporary televisual publicity:

The space of politics in ancient societies was the public space (square, forum, agora…). Today, the public image has taken over public space. Television has become the forum for all emotions and all options. We vote while watching TV. […] We are heading toward a cathodic democracy, but without rules. […] There is no politics possible at the scale of the speed of light. Politics is the time of reflection. Today, we no longer have time to reflect; the things that we see have already taken place. And we must react immediately… Is a real-time democracy possible? An authoritarian politics, yes. But what is proper to democracy is the sharing of power. When there is no longer time to share, what do we share? Emotions.

22

This compelling immediacy of the media, the magnetic pull of the image and the microphone, has been testified to by the highest officials of our government and military.

23 Images, they certify, do make things happen and sometimes too quickly. We can and should dispute the contention that discussion or sharing disappear in the putative instantaneity of the live transmission (as if it does not have its own temporality, its own internal structure, its delays and frames and decisions) but there is no debating the claim that the image (and especially the image of catastrophe) has the power to circumvent or pressure political institutions, and not just in democracies.

24In Somalia events did seem dictated by this CNN effect, with the attendant displacement of deliberation by emotion and hence the short-circuiting of the public sphere, whether it was a matter of the starving children, the proud international forces, or the dead American soldier. But what then of Bosnia, where everything seemed to be visible as it happened, and yet, on the contrary, it is said, virtually nothing happened in response? As David Rieff has written, ‘no slaughter was more scrupulously and ably covered’ and ‘it [did] no good’ – ‘we failed’ (1996: 223, 222):

Fig. 12 Warrior armored vehicle, Cheshire Regiment/UNPROFOR, Amhici,Bosnia- Herzegovina, April 22, 1993; video still from CNN, April 23, 1993.

The hope of the Western press was that an informed citizenry back home would demand that their governments not allow the Bosnian Muslims to go on being massacred, raped, or forced from their homes. Instead, the sound bites and ‘visual bites’ culled from the fighting bred casuistry and indifference far more regularly than [they] succeeded in mobilizing people to act or even to be indignant. (1996: 216).

If the lesson of Somalia was that cameras made things happen, and sometimes too quickly, Bosnia seemed to tell the opposite story: a brutal combination of overexposure and indifference. Somalia was hyperactivity; Bosnia inactivity, just watching. This was the clichéd meaning for which Sarajevo became the metonym. We are back to where we started: let me cite a few examples, from war correspondents themselves, of the trajectory that travels from a certain expectation about the putative power of images to despair at their failure and even to anger, from Mogadishu to Sarajevo.

Only nine months into the siege, in a dispatch that won her the first of many prizes for coverage of Sarajevo, CNN’s Christiane Amanpour reported on a creeping despair with the televisual:

Take any day in the life of this city. The sights are so familiar, perhaps they have lost their impact. Around noon another mortar falls. More people are killed and injured. They are rushed to the hospital. The emergency ward is full. Surgeons labor to save lives. The operating theatre is awash in blood. Early on in the war the staff were patient with photographers, hoping perhaps their pictures would shock the world into doing something. The world has done nothing and the doctors have lost hope and patience.

25

Years later, Giles Rabine, reporting live for France 2 from Sarajevo on 13 July 1995, just after the fall of Srebrenica, commented simply that, after thirty-nine months of televised siege, ‘the Sarajevans have had enough of being inter viewed, being filmed, being photographed; they’ve had enough of us watching them die, live, without trying to do anything to save them. And who’s to say they’re wrong?’

They were not wrong. Roger Cohen of the New York Times took this as the premise for his searching front-page report on ‘postmodern war’ in the besieged city one Sunday in May 1995. Postmodern for many reasons, but mainly because it’s a matter of images, of what the reporter finds to be a dangerously blurred boundary between event and representation, and of a certain paralysis, the apparent re-or dis-location of the field of knowledge and action to the screen of a monitor and the entry of those representations back into the field of the things and events they ought simply to represent. Here is his lead for an article headlined ‘In Sarajevo, Victims of a “Postmodern” War’, New York Times, 21 May, 1995:

Figs. 13, 14 & 15 Faruk Sabanovich, outside the Holiday Inn, Sarajevo, Bosnia- Herzgovina, March 3, 1995; video still from ABC, March 3, 1995. Source: RTV/WTN pool material via ABC.

Faruk Sabanovic, a pale and gentle-featured youth, is a thoroughly modern victim of war. He lies in the main hospital here with a video of the moment when he was shot and became a paraplegic. There he is, outside the central Holiday Inn, walking briskly across the street, his hair ruffled by the wind. The crack of a shot echoes in Sarajevo’s valley. He falls. He lies on his side. He is curled in an almost fetal position. A United Nations soldier looks on, motionless.

A Sarajevan man arrives, screaming abuse at the soldier, who eventually moves his white United Nations armored personnel carrier. This slight movement is enough to cover the civilian as he rushes out to retrieve Mr. Sabanovic, whose lithe body has turned limp. ‘It’s strange when I watch the video, I feel like it’s somebody else’, said Mr. Sabanovic, who is 20. ‘But I remember it so well. After I was hit, I felt my legs in my chest. Then I saw my feet. I tried to move them. But I could not. This United Nations soldier was looking at me. He did nothing. He just looked. For me, it was so long.’

The scene is shocking, doubly so by virtue of the videotape. The civilian victim is not only crippled by a sniper but is also in possession of the images of his attempted murder. The reporter can thus not only interview the person but watch TV with him. And the image is somehow not just of Faruk Sabanovic or of what happened to him on the street in Sarajevo; it is for Cohen an allegory, an image of something else, more confusing, an image of the confusion and loss of orientation – in images – which have affected our sense of reality itself. Watching this tape, with its inert star next to him, Cohen seems paralysed by the sight of people watching: ‘Faruk lies … with a video’; ‘a United Nations soldier looks on, motionless’; ‘this United Nations soldier was looking at me. He did nothing. He just looked.’

Thanks to images like these, we are all like that UN soldier, just looking, or like the cameraman, waiting. That is their rich allegorical meaning, their hermeneutic supplement: they mean the inaction that they demand of their producer and their viewer. Cohen adds:

The images capture more than the maiming of Mr. Sabanovic; they capture the increasingly surreal and sordid nature of the three-year-old Bosnian war. A civilian is shot on a city street; a television cameraman, waiting at a dangerous crossroads to see somebody killed or mutilated, films the shooting; a soldier sent by the United Nations as a ‘peacekeeper’ to a city officially called a ‘safe area’ watches, unsure what to do and paralyzed by fear. The elements of this troubling collage are also elements of what some military analysts are now calling ‘postmodern’ or ‘future’ war.

In the tape, in the hospital, Cohen sees an image from Sarajevo and in it the whole new troubling thing metonymised. As the space and time of what happens shifts onto the screen, even ‘there’ in Sarajevo, all sorts of boundaries are collapsing with it. He enumerates the transformation or the decay that coincides with the emergence of the videotape: states are replaced by militias or other informal groupings; armies and peoples become indistinguishable; central authorities disappear; and ‘live images of suffering, distributed worldwide, sap whatever will or ability there may be to prosecute a devastating military campaign’. Looking is not acting, in Sarajevo or in New York, and for Cohen the diffusion of images goes hand in hand with a more disturbing dispersion or evisceration of the conditions of action: lost are centrality, authority, borders and clear distinctions, principles, and all the rest.

The triumph of images figures this for Cohen: images sap the will in war, he says, and yet paradoxically it is a war of images, fought with images:

Mr. Sabanovic got in the way at a particularly dangerous Sarajevo crossroads. That is why there was a cameraman there to film his near-death. Because the spot is treacherous, the chances are good that a few hours of patience by a cameraman will be rewarded with compelling images of a life being extinguished or incapacitated.

A ‘compelling image’ is, of course, a weapon, and the cameramen sometimes seemed like the best gunners the Bosnian government had, being deprived of almost all other military equipment. Certainly most of the journalists in Sarajevo understood this, and recognised that their work was not simply impartial. Didn’t Somalia suggest, after all, that images could be compelling, that tele-guided public opinion could force action?

Cohen, in the late spring of 1995, has seen enough to withdraw that conclusion. There are no compelling images: ‘Thus, just as the world has long watched the crushing of Sarajevo – so endless as to become increasingly unreal – the people of Sarajevo may now watch from their hospital beds the moment they were crippled, so abruptly that comprehension is difficult.’

The image sparks a crisis, not just in action but in comprehension, and the sentence that speaks of it also tells the story of a more profound disturbance. ‘…So abruptly that comprehension is difficult’, he writes, but just what exactly happens so abruptly, the crippling or the watching? Surely Cohen means the suddenness of the rifle shot itself, caught on tape, but his dangling modifier betrays the ambiguity he is most alert to, the difficulty of discerning event and video repetition. In the face of this difficulty, Cohen proposes some reservations, or some objections, which although they are not formalised, and hesitant at best, do constitute something like a systematic critique of this ‘postmodern’ condition – it troubles him and with him, ‘reality’. Sarajevo becomes surreal, unreal, endless; there is too much watching, too much mediation, even there in Sarajevo, so that even the subject of the image is himself alienated from it, split from himself. ‘I feel like it’s somebody else’, says Sabanovic, now sharing the position of the immobilised one who just watches. The sniper and what Cohen calls ‘the twisted video’ together reduce everyone to a paraplegic – inert, paralysed by fear, just looking. And yet Cohen finds a moral for the story in the prone 20-year-old, ‘a strength and a conviction that rise far above the banal violence of his video with its succinct accounting of a directionless war in which civilians die live on camera.’ Without direction, pulling the very subject of the image apart from himself, the war of ‘live death’ comes to mean for Cohen at once an excess of imagery and a failure of the promise of those images – no action, no comprehension, only difficulty and a certain indetermination. Faruk Sabanovic, for his part, thanks the camera: the United Nations, he says, is ‘just here to ease consciences. […] And I know they brought me to the hospital in their ambulance only because the camera happened to be there. I have to say that I despise them.’

So in the end the two viewers of the tape disagree about its effects while agreeing that it has one, and these opinions recapitulate what I think represents the crisis of a certain idea of publicity. The symmetrical opposition of the interpretations – Mogadishu and Sarajevo – confirms that what is in question is the theoretical status and the actual function of the public image. Sabanovic believes in the CNN effect: ‘they brought me to the hospital only because the camera happened to be there’. Cohen fears that the camera and the watching cripples our responses, that ‘images sap the will’.

The strong version of his hypothesis has also been articulated by Jean Baudrillard, who thus forms a symmetrical pair with Virilio.

26 Baudrillard suggests that ‘Bosnia exemplifies total weakness’; ‘the West has to watch helplessly’, in a ‘military masquerade where the virtual soldier … is paralyzed and immobilized’ (1996: 87). And ‘the Bosnians … end up finding the whole situation unreal, senseless, and beyond their understanding. It is hell, but a somewhat hyperreal hell, made even more so by their being harassed by the media and humanitarian agencies … thus they live amid a type of spectral war’ (1996: 81).

Some American commentators have drawn radical conclusions from this proposition, and although it is in a certain sense highly disputable there is nevertheless something extremely important at stake here which this radicalisation can help clarify. In a collection of essays called This Time We Knew, edited by Thomas Cushman and Stjepan Mestrovic, an attempt is made to measure the significance of what seems an obvious failure: the last time around, we might have been able to say we didn’t know what was happening, but throughout the second genocide in Europe in this half century, we have no such excuse. Because of television and the rest of the ‘daily barrage of information and images’, it is not possible for ‘even the most disinterested viewer to ignore the grim reality of genocide’. Their ‘Baudrillardian’ hypothesis:

Lack of action proceeds … from the fact that the mediated images of the world are mere representations that lend an air of unreality to the things they represent. […] Media watchers lose touch with reality … stand passively by or engage in self-serving forms of ineffective action … [their] voyeurism and individualism feed[ing] on televised images of evil. (1996: 79)

And that means that the crisis is not merely one of inaction. In fact, what is lost in Bosnia is nothing less than the Enlightenment, and with it the discovery of the public sphere as the site where knowledge and action are articulated. They feel obliged to ask, then, ‘whether there is any relationship between the degree or extent of public information and practical or moral engagement by those who receive it’ (1996: 7).

The important point is that there is a sharp discrepancy between what we know and what we do, and this discrepancy has been neglected in most previous analyses. Yet this gap between knowledge and action is full of meaning for apprehending history as well as the present. In addition, this contrast causes us to rethink the success of the so-called Enlightenment project: the passive Western observation of genocide and other war crimes in the former Yugoslavia amounts to a toleration of the worst form of barbarity and gives us pause to wonder whether, behind the rhetoric of European progress and community, there is not some strong strain of irrationality that, if laid bare, would call into question the degree of enlightenment the civilized West has managed to attain at the century’s end. (1996: 8)

It is not clear just how far the two editors to that volume are willing to go in ‘calling into question’ the Enlightenment axioms that the ‘gap between knowledge and action’ in Bosnia provokes. The specter of ‘irrationality’ – always opposed to a normative reason – and the progressivist hint in the word ‘attain’ suggests that they remain committed to the project that has become questionable. But what happens if we seize on this insight – that the Enlightenment and its public sphere are in question – and try to move beyond the simple desire to recover it, to rescue it from its temporary loss. Suppose it were, precisely, the problem.

What failed in Bosnia? We often say that we failed, and we imply that

we are just this well-known public of the ‘so-called Enlightenment project’. But the more we rely on and retreat to the sense that the public sphere collapsed, the more we shore up just the notion whose apparent solidity may be implicated in the disaster. What if the belief in this public was part of the failure, if the faith in the obviousness, the evidence or self-evidence of the pictures and the automatic chain of reasoning they inspire, was not what failed but the very failure itself? What is at stake is the programme which expects that, as David Rieff put it, ‘one more picture, or one more story, or one more correspondent’s stand-up taped in front of a shelled, smoldering building would bring people around, would force them to stop shrugging their shoulders, or like the United Nations, blaming the victims’

27 – one more picture would force something to happen – what if just that expectation about information and illumination was part of the problem?

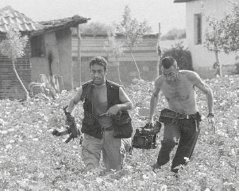

Fig. 16 AP TV cameraman Miguel Gil Moreno de Mora (left, with camera), Kosovo, 1998; photograph.

To draw out the most radical conclusion from Cushman and Mestrovic: what if it is some part of the ‘Enlightenment’, and not its failure but rather the faith we put in the informative power of images, that didn’t just fail to stop what happened but allowed it to go on? What if, because the cameramen and the images were there, and because they are supposed to make a difference simply by virtue of what they showed, the disaster continued?

Fig. 17 Christiane Amanpour, reporting from the Kosovo border, spring 1999, video still from CNN, date unknown.

Hypothesis: to the extent that we imagine or take for granted the articulation between knowledge and action, which seems to define the public sphere, it is bound to fail. But what can only be thought of as a failure in those terms is, in another sense, the success of a political strategy, and if we continue to think that images by virtue of their cognitive contents, or their proximity to reality, have the power to compel action, we miss just the opening of ‘new fields of action’ (Benjamin) that they allow.

So what if we think about this understanding of publicity not as a failure or as the re-emergence of irrationality, but as an alibi, a conceit or a consolation? These are words I borrow again from David Rieff, in Slaughterhouse, who suggests that it is this that has failed in Bosnia: a naive hope, a consolation and a conceit, the consolation of images and the dream of public information. Here’s the collapsed public in a sentence: ‘People … console themselves with the thought that once they have the relevant information, they will act. It is an old conceit’ (1996: 41). ‘It was the conceit of journalists …[:] if people back home could only be told and shown what was actually happening in Sarajevo … then they would want their governments to do something’ (1996: 216).

The conceit or fantasy of this kind of public sphere must, after Bosnia if nowhere else, contend with what we could call the rule of silence – no image speaks for itself, let alone speaking directly to our capacity for reason. Images always demand interpretation, even or especially emotional images – there is nothing immediate about them. This implies a second rule, that of unintended consequences or misfiring – the story of Bosnia is that images which might have signified genocide or aggression or calculated political slaughter seemed for so long to signify only tragedy or disaster or human suffering and hence were available for inscription or montage in a humanitarian rather than a political response. So what failed in Bosnia is an idea or an interpretation – and a practice – of publicity, of the public sphere as the arena of self-evidence and reason, an idea which now must be challenged, not to put an end to the public sphere but to begin reconstituting it.

As it happened, the images were open enough to demand only that we ‘do something’, and the problem concerns, in short, this something. The naive consolation is precisely that its content or meaning is self-evident, even analytically implied by the information itself, by ‘what is actually happening’. And ‘do something’ they did, in fact, something which amounted to, as Rieff puts it in the sharpest phrases of his book, ‘administering the Serb siege’ and ‘becom[ing] accomplices to genocide’ (1996: 147, 189). The combination of the traditional tasks of peacekeeping – which require military observers to be stationed on or between the front lines, and hence in the zone of any possible offensive military operations like air strikes – and the new humanitarian tasks of escorting convoys across lines of confrontation meant that the ‘humanitarian’ operation was an active impediment to any other action. Not just the ‘fig leaf’ which Rieff too lightly calls it but an affirmative choice: ‘the wish that there be no intervention’ (1996: 189, 176). And this project was best accomplished by undertaking the other intervention: stationing peacekeepers close enough to Bosnian Serb forces that they would either be targets of Western air strikes or easy hostages for the Serbs, and escorting the convoys that always made it necessary not to, as the UN put it, ‘compromise the humanitarian mandate’ by antagonising the aggressor. ‘This convergence of interest between the UN and the Chetniks was not an exceptional situation’, as Rieff says, but the very structure of the situation (1996: 175).

And it happened thanks to the images, from which we expected something rather different. But images, information or knowledge will never guarantee any outcome, force or drive any action. They are, in that sense, just like weapons or words, a condition, but not a sufficient one. Still, the only thing more unwise than attributing the power of causation or of paralysis to images is to ignore them altogether. If they can condition some action – and indeed, in Sarajevo and elsewhere, that’s exactly what happened – then it is only at the risk of this very indirection, the unexpected outcome, we might say: here, the humanitarian one. We cannot, at least not without repeating what seems to me to be the basic strategic error here, not expect the unexpected – we cannot count on the obviousness of the image, fall for the conceit that information leads ineluctably to actions adequate to the compulsion of the image, precisely because images are so important. There is no compulsion, only interpretation and re-inscription, and the image dictates nothing.

This fate of the image – left to wander and to drift from context to context, nothing but surface and frame – is what we can call, borrowing words from the reporter in Sarajevo, its ‘banal violence’, the banality of a ‘succinct accounting’ on video. The image has no guaranteed meaning, and remains only to testify, to demand, to induce a responsibility – even if, as Avital Ronell argues about the video-tape of Rodney King being attacked by the LA police, ‘it is a responsibility that is neither alert, vigilant, particularly present, nor informed’.

28 The responsibility of the viewer is co-extensive with the lack of self-evidence of the image: it dictates nothing, compels nothing. It can always be used, though, which is to say that it can and must always be interpreted, and the terrible failure of Bosnia was that a certain understanding of the public sphere – ‘the thought that once [people] have the relevant information, they will act’ – allowed or even produced an interpretive complacency. ‘Surely one more picture, or one more story, or one more … stand-up … would bring people around, would force them to stop shrugging their shoulders’ – nothing is less sure, less certain, precisely because we think that it is.

The question of surveillance teaches us, finally, that there is no ‘finally’ where its images are concerned. Images never speak for themselves, never make anything in particular happen, even if they seem often to make something happen and are now indispensable in war. In Bosnia, they opened a gap, issued a call, and in response came the humanitarian option, displacing all others.

29 This means that the accounting, however succinct, does not stop – the image remains, without guarantees, always available for reinterpretation and reuse, of necessity the focus of an endless vigil and a struggle for re-inscription. The battle takes place in public, in fact the public sphere is constituted by the irreducibility of this battle, not the public as the last refuge of that dream or consolation of information properly acted upon, but another public, space and time, virtual and visual and nevertheless real enough, tenuous, uncertain, where everything is open to abuse and appropriation; shaky ground indeed.

Some years ago, Virilio warned in

Le Monde Diplomatique that, far from merely offering new opportunities for exploration or relaxation, the media of which telegraph, telephone, radio and film were the merest announcements have by now radically accelerated and generalised the transmission of event and signification, and indeed absolutised it to the point of instantaneity, such that places no longer matter. He wanted us to believe that, when surveillance is ubiquitous and its output moves at the speed of light, new media now threaten to deprive us of places altogether, inducing not simply vertigo or disorientation but a more radical ‘de-situation’. In an age of real-time communications, of ‘instantaneous, globalized information’, Virilio saw nothing less than the disappearance of the world itself in a ‘tyranny of absolute speed’.

30In other words, the vertigo is absolute and unceasing, depriving us of ourselves. Far from creating a new world citizenry, a virtual community of humanity freed of allegiances to anything other than other humans as such, blown by the technologies of ‘anywhere’ out of the local particularities of place and identity, what disappears here is humanity, the relation to the other. When what happens there happens here too, in real-time, for Virilio what we lose is the fold of reflection, the gaps and delays that make decisions possible and debatable, that divide them into and across more than one instance.

‘This goes beyond CNN. Actually, CNN is history’, Virilio told a reporter. ‘And it has nothing to do with the current surveillance of parking lots and street corners by security cameras. […] We’re witnessing today the deployment of a new, global tele-surveillance system whose impact will be far more profound than that of the traditional television.’

31But as surveillance goes global and speed crosses the barrier into instantaneity, do time and responsibility, and with then the possibility of democracy, disappear? Storage and montage happen in so-called ‘real-time’, of course excess time is built into the transmission, into the mediation that defines any technology of inscription. ‘No longer time to share?’ Not quite.

In addition to the vertigo of acceleration, there is also a more subtle vertigo of deceleration, of slow motion. What Benjamin called ‘the dynamite of the tenth of a second’ means that fast and slow cannot simply be opposed to one another. What is destabilised is the privilege of the present, the experience of the human subject and its self-present reflection (deliberation, reason, judgement), which would seem to regulate the transformations of speed. But only the most classical metaphysics of the subject and of presence can see in this the end of politics, the disappearance of the public sphere in the pure surface of the image. And only an excessive commitment to some ideology of the real imagines that time and decision evaporate in the light of the television screen. What speed teaches us is that this surface is itself folded, temporally or rhythmically complex and heterogeneous, that there is always an ‘interior’ lag which divides the subject from itself. It is this division which makes possible, in fact, the sharing that defines democratic conflict. We cannot simply say, ‘warning! slow down!’ – as if the distortions of speed could be undone and the self-identity of the present reinstated, and with them an anachronistic definition of the political, the public and the instance of decision. We can say, though, that the vertigo of deceleration – the slow motion of even the fastest and most ‘compelling’ image – tears us apart from our solid selves and opens the possibility of a decision, even of a properly political relation to others, in the question it poses. We are not quite out of time, but the image does not provide the answer for us either.

NOTES

The author and editors are grateful to PMLA for allowing this chapter to be re-printed.