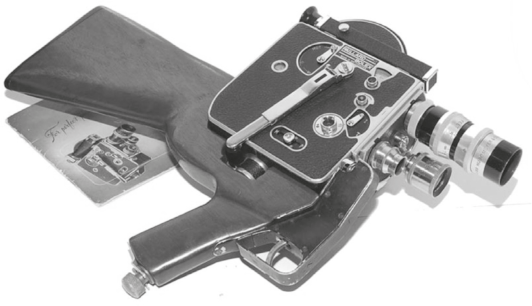

Fig. 1 Bolex with Pistol Grip.

It is a curious and not insignificant etymological coincidence that in some languages, the verb ‘to shoot’ is used to mean both the firing of a gun and the filming of an image. Ever since the invention of the moving image, there has been an intimate and mutually dependent relationship between the camera and the gun. One of the very first prototypes for the motion picture camera, Etienne-Jules Marey’s ‘Fusil Photographique’, was fashioned out of and modelled upon the revolving rifle able to ‘shoot’ twelve photographs per second in rapid succession. Here, at the origins of cinema, we find an inspiration less innocent than implicated, where the sightlines of a camera mimic and will come to eventually support the sightlines of a weapon.

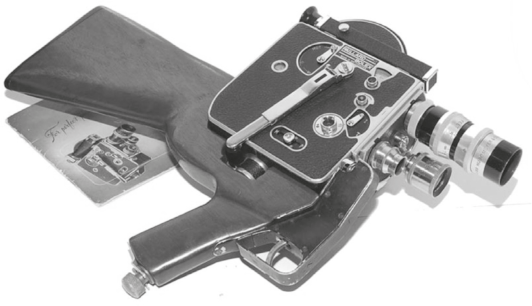

Fig. 2 Etienne-Jules Marey’s 1882 invention, ‘Fusil Photographique’, an early experiment in recording motion on film.

Guns and cameras have an obvious affinity that precedes the invention of the cinema.

1 The framing and tracing of movement through the ‘viewfinder’ of a gun, along with the mechanisms supporting its agility and efficiency, are eventually mimed by the cinematic apparatus, further nourished by the vast investments in the development of weaponry that is guided by, and/or monitored through, the lens of a camera.

2 For several decades, weapons have been developed whose precision depends heavily on the ‘eye’ of the camera requiring only a technician, based in a far away post, to focus, aim and fire.

3 In his book

War and Cinema, Paul Virilio writes extensively about the interpenetration between warfare and cinema – not exclusively about the gun, but about the entire apparatus of destruction. There is what he calls ‘an osmosis between industrialized warfare and cinema’ so ultimately enmeshed that he is moved to assert that, ‘War is Cinema, Cinema is War’ (1992: 58, 26).

4We learn from Virilio that wars are no longer fought without cameras – and have not been since World War II, when Hitler sent a cameraman out with every battalion (1992: 56).

5 By now there is a thorough integration of cinematic tools in warfare (and, at least in some countries, of the military’s participation in the making and advising of war films). The gunsight and the camera eyepiece not only engage a similar operation of framing the target, with a shared privileging of the ocular faculty, but in fact the camera and the weapon are frequently conjoined, aiding and abetting the other’s operations – as cameras are used to spot targets, perform reconnaissance, train marksmen, built into military aircraft and mounted onto rifles and missiles, to capture and record the moment of ‘impact’.

6But if Virilio exhaustively recounts the relentless imbrication of armed conflict and cinema, he does so only in relation to fiction film. Despite the obvious fact that the images taken from aboard the unmanned planes, all-terrain vehicles, robots and anti-tank weapons are documentary in nature, Virilio and others writing about the relationship between cinema and war,

7 rarely if ever acknowledge the link between visual realist modalities of filmmaking and violent conflict.

8 Instead, their sights are set on the spectacle of the fiction film, especially the action and war genres, most particularly those made in Hollywood. This essay attempts to refocus attention back onto visual realist modalities – whether documentary or otherwise

9 – where in effect, it all began, and where it still continues to play an undeniable role in representing and mediating zones of violent conflict. It will trace its way through the question of the frame, initially in its literal sense, and ultimately in a more figurative fashion.

Fig. 3 Rokuoh-Sha Type 89 WWII Vintage Machine Gun Camera, used mostly for target practice.

Initially, I want to situate the discussion by examining the two distinct positionalities that visual realist filmmaking can take within the context of violent conflict zones: the Gunsight POV – shooting from the perspective of the bullet; and the Barrel POV – shooting down the barrel of a gun, in the line of fire. As Harun Farocki’s

Image of the World and Inscriptions of War (1989–90) attests, the point of view from which visual material is shot does not and cannot exhaust its semiotic valences nor its hermeneutical potential.

10 It does, however, speak volumes about the relationship between aiming and framing, or said otherwise, the power of the frame, the power to frame and reframe. The purpose for which the images are collected and disseminated, the allegiances an image is meant to forge, the information and intelligence it is meant to gather, the power, or lack thereof, it may represent, and the way in which images are literally and figuratively framed, are all valid reasons to distinguish between these two divergent sightlines. It does, after all, matter from which side of the gun you’re shooting, not to mention what is included in and what is left out of the frame. In this essay I will be discussing three specific projects, with attention to the pressing question of point of view and framing. The larger aim of this article is to explore the limits of the ‘encounter’, or better, the ‘confrontation’ between the two apparati – the camera and the gun – and the broader ‘frame’ in which these images are captured and disseminated.

The crucial distinction to be made here between the Gunsight POV and the Barrel POV is whether the camera is positioned as an extension of the gun or as a response to it, in effect ‘shooting back’. In cinematic terms these two positionalities can literally represent the shot/reverse-shot structure, though the key difference would be that the ‘shot’ wields both literal and symbolic power while the ‘reverse shot’ in this case is arguably consigned to the symbolic.

11 In that both wield symbolic (and phallic) power we have to enquire as to the machinations and mobilisations of that power, and we must then consider what may occur in the one instance (the Gunsight POV) where symbolic power is concomitant with destructive force.

Scopophilia and voyeurism, the twin regimes of the repressive patriarchal cinematic gaze, clearly take on more than symbolic implications when allied with, and to a much lesser extent against, a lethal weapon. Not unlike the dagger at the end of the tripod leg in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), the camera is more than a threat in representational terms, becoming part of a much larger apparatus of death and destruction. Today’s riot police squadrons routinely dispatch their minions, interchangeably wielding batons, tasers, guns and cameras, all in pursuit of the same repressive goal.

Although the visual images rendered from the Barrel POV remain in the symbolic realm, they are nonetheless caught in the sight lines of an ‘adversary’ for whom this is not the case, posing potentially very real and dire consequences in this lopsided ‘Mexican stand-off’. Whether there is any such thing, really, as purely symbolic power, and whether indeed the effects of the Barrel POV-oriented camera do in fact also have ‘real world’ effects, remains to be explored.

GUNSIGHT POV – THRILL OF THE KILL

The most common modality from the Gunsight POV is official, governmental, military or paramilitary imagery. The Gunsight POV can, of course, also partake of several other visual realist modalities. When, during the second Gulf War, the US Defence Department gave journalists access to its maneuvers as long as they agreed to be ‘embedded’ within a military platoon, we see a clear example of journalism’s collusion with the Gunsight POV. A spate of documentaries made from the soldiers’ POV, some making extensive use of helmet cams (

Gunner Palace, Petra Epperlein, Michael Tucker, US, 2004;

Restrepo, Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger, US, 2010, and; the British TV documentary series

Our War, a three-part series produced for BBC3 by Colin Barr, 2010–11) all attempt in a sense to put the audience in the shoes (or head?) of the invading military units as they make their way in unknown and dangerous territory, eagerly taking on the Gunsight POV, albeit one that also has guns aimed at it. The effect of much of this material can be insidious. In the case of both

Restrepo and

Our War, the spectator’s perspective essentially mimic’s the soldier’s, and just as they at first find themselves disoriented and uncertain of their feelings (why are we here, what is this place), so does the viewer. As soon as the first soldier is killed, the identification between viewer and soldier, by virtue of POV, is strengthened. The viewer is brought into the war as a virtual participant, the soldier who gets shot in front of ‘us’ could just as easily have been ‘us’. Thus as the soldiers gain a sense of purpose that suddenly gives meaning to the operation – revenge and retribution – even if that meaning masks the vague and unconvincing premise that may have brought them there, the viewer has been positioned to share their vengeful sentiment, identification having been seamlessly effected; this process, of course, conveniently sidesteps those nagging questions (why are we here, by what right), insinuating the viewer as part of the ‘we’ who are going to make ‘them’ pay.

Not all Gunsight POV is one-sided. There are countless YouTube postings of amateur video shot on camcorders or mobile phones by soldiers, militia fighters, jihadis and mercenaries in places like Iraq, that when seen back to back in compilations such as Mauro Andrizzi’s How We Fight, Part I (Argentina, 2008), give a sense of the shot/reverse-shot that can occur strictly from the Gunsight POV. That is to say, both sides are shooting to kill.

I would like to briefly describe a clip from Mauro Andrizzi’s

How We Fight, Part I to give a sense of the investments of the Gunsight POV. The play of the title empties the promise of an ethical answer to the question of ‘why we fight’ (the title of the US War Department’s World War II documentary propaganda series directed by the likes of Frank Capra and John Huston – a promise admittedly never fulfilled) into the more mechanistic and pragmatic problematic of ‘how’. The project as a whole is a compilation video comprised of footage taken by participants in the Iraq conflict (Iraqi militia fighters, Iraqi military, US and UK military, mercenary fighters, civilian workers). The majority of the material was downloaded from YouTube by the Argentinian director, Andrizzi. In one brief extract we hear the voices of several young American soldiers, as their unsteady camera peers out of their vehicle’s windshield, looking at a generic industrial landscape. The moment is charged with their agitated anticipation. The young man behind the camera asks the presumably more experienced soldier how long he should continue to film for, to which he receives the sage response: ‘until you turn it off’. They wait impatiently for the missile to come, launched, we understand, from a nearby position, perhaps by members of their own battalion. They clearly know the target and the timing of the launch and it’s only the filming of it over which they seem to lack mastery. Nonetheless, there is thorough identification between the missile strike and the filming of it, as the soldiers exclaim with whoops and hollers and phrases such as ‘hell yeah, bitches,’ ‘that was so fucking beautiful’, ‘see you in fucking hell’, when the projectile finally hits its mark. Ultimately, when the missile strikes, mastery over the visual image is also achieved, as we hear the novice videographer brag before cutting, that he ‘got it all’ on tape.

This clip differs dramatically in tone (but not in alliance between the camera’s POV and the attack) from its countershot, as it were, one of the many Iraqi militia clips also included in the compilation, where we hear a fighter chanting Allah’s name repeatedly, with strained voice, before and after we see a (usually successful) strike. Faith and discipline characterise the tone of the latter extracts, whereas the unruly excitement of a high-octane videogamer characterises the former. In both cases, however, we witness the unity of vision, a shared objective between the camera and the apparatus of destruction. There is a clear affinity here, a symbiosis of vision as a nexus of power. The gaze acquires its properly lethal aspect where to be shot by the camera is in essence, synonymous with being shot. The objective of the camera here is to capture the moment of impact – the ‘money shot’ if you will. It goes without saying that there are, of course, even more explicit and direct affilliative scopic relations between the camera and the gun, and the position in which the viewer is placed vis-a-vis this material is inevitably fraught, implicating the spectatorial gaze in the military might being brought simultaneously to bear. For instance, watching reconnaissance footage taken from an unmanned drone flying a mission over Iraq and broadcast on the corporate/commercial news conglomerates in the US, or footage from a ‘smart missile’ moments before it strikes its target, combines the thrill of being let in on a secret, the satisfaction of prosthetically allying one’s gaze with high-tech precision aim, and the vertiginous dawning realisation that one is being made to identify with a lethally destructive force, which has a passive dimension of approbation: by witnessing, not to mention taking pleasure in the spectacle, we are tacitly interpellated into the frame as accessories, no longer ignorant of the destruction, but in a manner of speaking, aligned with it.

When used in the ‘theatre’ (perhaps we should call it the ‘cinema’) of combat, a camera cannot be conceived of as a passive recording device. It is transformed into an instrument of war. As Allen Feldman suggests in his article ‘Violence and Vision: The Prosthetics and Aesthetics of Terror’, optical surveillance such as this can and often is regarded by the opposing force – with good reason – as tantamount to aggression.

12 The identification of the camera with the gun in these settings is not merely an allusion to repressive power, it is a direct mechanism of that power. The footage recorded amounts to intelligence gathering, and can be used in any number of ways against human and other targets. To be caught in the sightlines of the enemy’s camera, is to foreshadow being caught in the crosshairs of the enemy’s gun.

When Feldman was conducting his fieldwork in Northern Ireland in the late 1970s and into the 1980s, he saw very little in the way of oppositional or activist media, though it is known to have developed there later. Still, from the beginning of the conflict, the camera was an integral weapon in the defensive arsenal of warfare and it was treated as such. Framing and focusing a camera lens on a human subject by any of the warring factions was tantamount to an act of hostility.

BARREL POV – SHOOTING BACK

Civilians shooting back with a camera, without the apparatus of warfare supporting and sustaining it, while perhaps still regarded by the state and its militaries as a provocation, cannot and would not be eager to claim, I believe, such a thorough-going imbrication with destructive force. It is also rarely allied with the governmental and official realist modes of filming (such as reconnaissance, or target identification), but is much more commonly affiliated with the journalistic, documentary, activist and civilian modes of filmmaking.

13I will focus my attention here on two ‘Barrel POV’ projects: the first is a documentary entitled

Burma VJ (2008), and the second is an NGO-sponsored activist project associated with a well known human rights organisation based in Israel/ Palestine, called, appropriately enough, Shooting Back.

14Burma VJ is credited as a film by Anders Østergaard, a filmmaker initially working on a project about a group of Burmese video journalists/activists who had been shooting news footage illegally and sneaking it out of the country, in defiance of their government’s harsh censorship laws, when the so-called ‘Saffron Revolution’ broke out in 2007. In the end, the film chronicles the events of the Saffron Revolution made to look almost as though the amateur video journalists (the VJs of the title) were coordinating its developments. The film shows the monks of Burma leading popular demonstrations for days on end in a face-off with the currently ruling military junta, one of a succession of juntas that have mercilessly ruled the country without respite since 1962. Burma VJ features the raw footage shot by the video journalists/activists who braved life and limb to capture the month-long uprising on their small, easily hidden, camcorders. The mere possession of a camcorder in Burma at the time was a prosecutable offense-carrying a prison sentence of up to 25 years. A powerful film, it took the festival circuit by storm, winning top prizes at IDFA in 2008 and Sundance in 2009.

The footage is gripping, and the bravery of the citizen journalists turned video activists is beyond doubt. Their stated goal (as conveyed via voice-over of a VJ code-named Joshua – not credited as writer, however, in the film) is to show the world what was happening in Burma, then as now, a country closed to foreign press. As these images were successfully smuggled out of Burma during the course of the events, finding their way onto CNN, BBC and indeed via satellite back into Burma, the video activists can claim to have been successful in their aim.

The film has been praised by the Western press as being as suspenseful as an action film, made all the more powerful because it is ‘real’.

15 What critics seem to be moved by is the sense that the events are unfolding before their eyes. This effect is partly created by the interspersed re-enactments stitching this raw material together, preserving a sense of immediacy – placing the spectator ‘in the moment’.

This illusion of ‘presence’ is of course a conceit, because while the archival footage was shot live during the events’ unfolding, the story that weaves it into a coherent narrative is constructed for the purposes of the film. The ‘lead character’ Joshua, played by an actual Burmese VJ who did indeed escape Burma, is seen in several scenes set both within and outside of Burma, engaged in conversation with his comrades, often coordinating their elicit activities or receiving breaking news about the whereabouts of one of their number. This was scripted and reenacted for the benefit of the film, yet by seamlessly intercutting the re-enacted material with the archival, the film’s sleight of hand renders it somewhat suspect, as if entertainment value and narrative flow take precedence over the historicity of the archival material. There are also re-enacted scenes that are shot so as to appear as if they were part of the secretly filmed footage of the VJs, for instance, a scene where the activists aren’t sure anybody will turn up for a demonstration, and the footage appears to be shot illicitly from across the road, as protestors start coming, first one, then another, and soon many begin to stream in. This footage, though one might never suspect it, was staged, and its power to move the viewer rests precisely on the fact that we think it’s an artefact produced under extremely dangerous conditions; a testament to the grit of the intrepid VJs.

This relentless staging and re-enacting in the service of the all important demands of narrative coherence, also serves to suppress the gaps, the lacunae, the ultimate inadequacy of the coverage, rather than considering such shortcomings to be a consequence of the general state of repression which would have allowed it to be imagined and understood as such by the viewer. The staged material does provide a dramatic platform on which to set the tense and engaging, if chaotic, original footage. But one wonders if it doesn’t also reduce this unique event into a generic action/suspense spectacle, with all of the habitual responses to such genre films, at the ready.

Also in the service of a seamless narrative – the conventional film’s ruthless master – a great deal of relevant information is elided, such as the fact that the monks in the film appear to be a unified force, though after nearly half a century of military dictatorship in which the monks are ‘highly respected’, and where religious sites turned tourist attractions like Manderlay are major sources of foreign currency, it is impossible to imagine that there weren’t conclaves of corrupt monks. This, alongside the fact that no real reason is given for this spontaneous uprising, though of course there were many factors that triggered it, including the neo-liberal move by the junta to eliminate fuel subsidies which caused the price of diesel and petrol to suddenly rise as much as 66 per cent in less than a week,

16 make one suspect that the director wanted to streamline the story so that it was freed of any geopolitical particularities and could appeal to a ‘universal’ audience. Armed with the platitudes of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’, and the elements of a particular struggle with all of its local cultural specificities effectively erased, what is left is a good crackling drama, of the sort any movie goer is familiar: a tense, action-packed, adrenaline-fuelled stand-off with high stakes, augmented by bright, ‘exotic’ colours. By conceding to the generic demands of an action film, keeping the viewer on the edge of her seat, heart pumping, palms sweating, one senses that the effect and political potential of the Barrel POV here, where real not ‘pretend’ lives are at stake, is flattened into well-worn formulas, rendered generic, made utterly familiar, and thus ultimately blunted.

17One aspect of this conventionalisation is the highlighting of the sense of danger. This is done by frequently foregrounding the act of filming itself. In this age of cynicism, there is something almost irresistible in the prospect of real-life heroism, which is to be had in abundance with our fearless videographers, putting themselves in the line of fire at every turn. Their heroism, in fact, is not at issue. They truly are worthy of great admiration and respect. Their footage may at times appear to be shot from the vantage point of a sniper, but even so, we cannot help but be aware that it is they who are potentially caught in the crosshairs of the sniper’s gun. Throughout the film, the risk to the video ‘shooter’ is palpable.

A pivotal scene in

Burma VJ features the shooting by the Burmese military of a lone foreign journalist, Japanese cameraman Kenji Nagai, at point-blank range. It is captured by several of the VJs from different angles (from a position above, from street level, head on, side view) – a testament to what appears to be their surreptitious ubiquity, at least at this particular moment. The footage is slowed down and played both forward and in reverse for the viewer. Here we are shown the consequences of being caught filming in Burma. Just as Feldman indicated with reference to Northern Ireland, in Burma too the camera is treated as a provocation, tantamount to a gun: a challenge to absolute authority and a claim to the right to frame and thus attenuate that power, despite the fact that this ‘gun’ would appear to be shooting blanks. The power of the media is in effect affirmed, in that it is deemed worthy of extreme measures of repression, perhaps even regarded as an enemy of the state. We learn earlierin the film that Joshua – our narrator’s codename – had been caught filming days before but only briefly detained. But by the time this Japanese journalist enters the fray, the situation had become even more critical.

18 The consequences of filming seem real enough, and the high stakes motivation would seem to be to mediate the moment for the world to witness.

Fig. 4 Japanese cameraman Kenji Nagai shot by Burmese military at point blank range.

Despite the airtime the original footage received on Western media outlets, even prior to its recontextualisation in this film, I believe it is necessary to question the efficacy of such exposure, or at least to question whether exposure, in and of itself, ensures a response. Is seeing and being seen, including garnering airtime on major media outlets in the West, an effective organising strategy in and of itself? Put another way, ‘what difference does it make that the camera was there?’, a question provocatively posed by Thomas Keenan in relation to the heavily mediated yet relatively ignored battlegrounds in Sarajevo. Keenan argues forcefully against any assumption that would automatically link the mediation of an event with a call to action. He reminds us of the distinct lack of interest in, and the extremely delayed response of European and North American governments to, what by all accounts was a policy of ruthless genocide taking place in plain sight. By Keenan’s reckoning, the siege of Sarajevo was one of the most heavily mediated conflicts of the 1990s. And yet, the saturation of images of the atrocities, instead, seems to have had a palliative effect, reassuring viewers that someone was there to witness in their stead (2002: 113).

19 Of course the Burmese VJs have multiple tactics and strategies beyond simply wanting their footage aired on international news outlets (including boycotts, litigation and using their footage to lobby foreign governments and mobilise student groups), but they are not alone amongst activist media groups to have international television exposure as a key component of their campaign. The emphasis placed on such televisual outlets by this group and by B’Tselem, the group I will discuss shortly, suggests the need to interrogate just what the role of the media may be. After all, as it stands today, it is by no means a neutral platform.

Having footage broadcast (pre-edited or otherwise) – and thus ‘framed’ – by global corporate and/or national media conglomerates, Keenan reminds us, does not guarantee a response, nor is it certain to influence policy. It is not even certain to change opinions. All it can do is inform and that within a contextualisation of the network’s own design. One cannot expect the corporate and/or national media of the world to act outside of its self-interest, as a neutral conduit of the information presented to them by activists. If anything, it serves as inexpensive content, shot in places where the Western media either does not have access (Burma, or more recently, Syria), or has not gotten the footage in time (for example, footage from the Egyptian events in Tahrir Square at the beginning of the revolution of 2011, or in Iran during the Green Revolution). Such footage, shot by amateurs, is often circumscribed with the caveat that the news media outlet cannot verify the material as it was not shot by one of their own camera people, thus not only indemnifying them from legal claims, but also instilling doubt in the viewer as to the veracity of the footage itself.

20 Furthermore, entire discourse analysis theses could be written on juxtapositions, both within newscasts, and with intervening advertisements when present.

Emphasis on getting the message out through every available channel, without consideration of the way that footage may be framed, can lead to matters going well beyond the makers’ control. While this risk may be deemed worth taking, the arguments in favour of exposure, without attending to context and framing, seem amiss. Yet it is not only the corporate or national newsmedia whose framing devices can be suspect. I will argue that Burma VJ’s own framing device has motivations beyond the Burmese VJs control, an issue explored further in due course.

THE ACTIVIST PROJECT: SHOOTING BACK, B’TSELEM

The Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem’s Shooting Back project, whose name was changed in 2008 by court order to the anodyne Camera Distribution Project (and as of the writing of this article, simply referred to on their web-site as ‘the Camera Project’), also actively invites international press attention, with a high degree of success. Here, as with

Burma VJ, we have amateur videographers facing off against aggressive, potentially lethal, forces. The project, however, does not produce documentaries

per se, but rather activist clips usually edited by B’Tselem staff, sometimes complete with an English or Hebrew commentator track, which can be sent out as press packages and propagated over the internet. They are also compiled on DVDs, usually based on themes or geographical areas.

21Another key difference between

Burma VJ and the Shooting Back project would be that the latter constitutes an exercise or expression of a legal action, one that is meant to test the limits of an already existent legal framework in which the actors have the right to film and document the situation (a right that may be arbitrarily and prejudicially enforced, but one that nonetheless exists). The material gathered can and frequently does serve as visible evidence of the most literal sort – evidence of abuses and excesses to be used not only in the ‘court of world opinion’ but in an actual court of law. Relative to the circumstances surrounding the shooting of the Burmese material, there would seem to be a tacit permissiveness associated with the B’Tselem project, as it is clearly known in the region and lends some measure of credibility, if not protection, to its videographers.

22To wit, in one of the video clips released in 2007, and in another shot in 2008, we hear a Palestinian cameraperson who is being attacked by settlers and/or confronted by soldiers, respond in Hebrew to the provocations with the claim, ‘

Ani mi B’Tselem’ (‘I am from B’Tselem’) which is particularly intriguing for the authority that statement hopes to invoke.

23 The two cameramen’s responses are meant to convey an entitlement: ‘I have the right to shoot, I’m with B’Tselem.’ This claim is all but unimaginable, of course, in the Burmese context. In one of the more recent clips though, it is the B’Tselem affiliation of the camera person that provokes a soldier to arrest him, saying on camera, ‘if you’re with B’Tselem, I’m arresting you too’. This despite the fact that the camera person had a legal right to shoot.

Several of the Shooting Back project’s shorts depict direct encounters with hostile forces. Some are shot surreptitiously, as when a man secretly films an illegal Israeli Defence Force (IDF) house demolition from his window.

24 Others film direct confrontations with soldiers and/or Israeli settlers who mean them harm. Some are shot in the absence of actual guns, as when a young Palestinian boy manages to avert Israeli settler violence by chasing them with his camera. The camera here operates with a similar deterrent effect as a gun. Yet what is mobilised is not might but

sight – the potentially damaging effects of witnessing, being caught (on tape) in the act of violent activities, tacitly supported by the state, reveals something of the limits to the settlers’ own internal justifications of their actions. Clearly they know they are doing something wrong, if not immoral (and all of these settlers are wearing the garb of religious Jews), as at least the settlers in this video seem to fear being seen by others. However, there are other videos on the B’Tselem website where settlers are seen throwing rocks in plain view of the camera with no restraint,

25 and in yet another video, a young Palestinian girl catches on camera masked settlers with clubs attacking a shepherd in his field. Despite the likelihood that these are different settlers in a different field, it is as if the settlers learned their lesson from an earlier video and simply went back to get their masks to hide their identities while they continue with their brand of terror.

26 In these cases, the camera may be a witness, but it is no deterrent.

One of the best known videos of the project,

Tel Rumeida (2008),

27 is shot by a Palestinian woman in Hebron, who is being tormented by her Israeli settler neighbours. She videotapes their abuses, which include verbal provocations as well as physical assault with stones, as Israeli soldiers look on. When the fully armed soldiers do intervene, it is generally to tell her to stop shooting, as if she is the one provoking the violence and her camera is obviously seen as a threat. At one point she runs out of her barricaded house into the perilous streets (as several young settler children pelt rocks at her and her little brother, who she is attempting to protect), and the soldier addressing her is apparently less concerned for her safety than about her continuous videotaping. He repeatedly tells her to stop shooting and although she keeps the camera rolling throughout, we see an image that indicates she has pointed the lens downwards, in essentially the same position as the soldier’s gun. There is a meeting of the ‘guns’, both pointed downward in a gesture of non-confrontation: a tense conciliatory stance that nonetheless implies the potential for a standoff – camera lens to gunbarrel – but manages to avert it. While the camera may not have the same lethal force as the soldier’s machine gun, the power it does have, to record, to witness, to confront, to intimidate, is clear for all to see.

We can see that the camera in these shorts, shooting from the Barrel POV, has different and at times conflicting effects. It can act as a deterrent, a witness or, indeed, a provocation. When acting as a deterrent to violent confrontation and/or illegal and illegitimate exercises of power, one can see the justification for its use. Similarly with witnessing, as the material can be used as evidence in both legal courts and the ‘court’ of public opinion. However, when it acts as a provocation, inciting or exacerbating an already volatile situation, there is a questionable value to the footage, both in terms of its status as witness and in terms of the risk in which it places the camera person. Suddenly and without warning, the B’Tselem affiliation shifts from shield to target, making it a liability for the person shooting from the Barrel POV.

I’d like to now shift the discussion from the question of the literal sightlines (POV) of the camera to the positioning of the material more broadly – the figurative framing devices of the two projects, B’Tselem’s Shooting Back videos and Burma VJ.

The stated intent on the B’Tselem website (and on the jacket covers of the widely distributed free DVDs) is to expose the everyday reality of occupation, the daily abuse and indignities, the relentless and demoralising struggles, ‘to show’, as they would have it, ‘the seldom seen’. However, in this decades-long occupation is there really any aspect of this struggle that can be said to be seldom seen? Not unlike the siege of Sarajevo that Keenan writes about, this conflict is easily one of the most mediated of all conflicts in history, with what seems like every angle covered by every possible mode of representation. It is perhaps not the specific situations that we haven’t seen, but the POV that is new. But this is not what is emphasised on the promotional materials. It is simply asserted that we are to see the seldom seen, as if in and of itself, this ‘seeing’ could catalyse change. Now, this is not to reduce the work that B’Tselem is trying to do more broadly. This project is just one facet of the campaigning work they do against the excesses of the occupation. B’Tselem is a human rights organisation that uses all of the tools at its disposal, including video, to attempt to affect the conditions under which Palestinians are living in the Israeli-occupied territories.

28 I will not address B’Tselem’s mandate as a whole here. I am strictly addressing myself to the claims made on behalf of the Shooting Back/Camera Distribution Project, which figures quite prominently in the organisation’s promotional material.

Taking into consideration Keenan’s important intervention, we must acknowledge that over-mediation, regardless of the POV, can misfire badly, and rather than inspiring the intended political response, can easily be naturalised as a site of ongoing human suffering, inciting in the viewer only pity and at best leading to some form of modest humanitarian intervention. There are consequences to this strategy, hinted at in Slavoj Žižek’s book

Violence.

29 While ameliorating harsh conditions is welcome, it may nonetheless ultimately mask larger problems. Žižek urges us to consider whether liberal humanist representations and condemnations of violence, such as those promoted by the Shooting Back project, merely register ‘subjective’ violence (the most visible yet superficial of all violences), while remaining mute in the face of underlying causes, unable to intervene in systemic, or what he terms ‘objective’ violence (2008: 9–10). How can the images of this project help us analyse the systemic violence of the Israeli occupation or even more profoundly, the military-industrial complex that sustains it and Israel’s economy? In what ways can such representations hope to disrupt the relations of domination inherent in that system?

Žižek, in line with several prominent leftist thinkers including Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Naomi Klein and Eyal Weizman,

30 finds the ameliorative effects of ‘humanitarian’ projects, of which activist media such as Shooting Back is a part, neither address the constitutive issues enveloping the violent oppression (in this case the Israeli Occupation), nor can they hope to lead to an end to the injustices that they depict. All they can achieve within the logic of the occupation, is to alter the superficial conditions of such abuse, of the ‘subjective violence’, and of course, while some relief is not to be rejected, unless the root causes are addressed, the misery will be no closer to an end. The change they may bring will be minimal and often, temporary, as we see in the Hebron video where a B’Tselem team films a break in the illegal blockade of a main street, only to find soldiers days later ignoring the law and continuing to bar Palestinians access to that same street. Change can be fleeting and even reversible. Israeli law, based on precedent like the British model, is arguably affected by any case that is won on behalf of human rights. However, the logic of these precedents is such that they apply only very limitedly and specifically so perhaps a type of roadblock will be removed or a shelter for the sun provided; perhaps soldiers will be disciplined for particular practices, or a type of torture outlawed, but change at that pace – case by case – means it will take a few lifetimes for the occupation to be dismantled.

Don’t get me wrong, the act of shooting back with a camera is not without its uses. It may be used as a visual record for future war crimes trials, and as stated it can and has been used as evidence for courts of law. The videos are indeed, as mentioned earlier, used as legal evidence, and may actually have a limited effect. Such effects are welcome in the short run, but whether they can end the excesses of the occupation as a whole remains an open question. In addition, it is not unprecedented for such projects to be used by the repressive forces to make the occupation more efficient, possibly more legally viable, and ultimately more entrenched. There are countless ways in which the Israeli government and the IDF have ‘improved’ their legal standing vis-a-vis the occupation, studying material made available through projects like Shooting Back, or Yoav Shamir’s

Machsomim (

Checkpoint, Israel, 2003), and then making minor adjustments to their practices so as not to be held legally liable.

31 Remember, these video images are widely available, and not only to those who might wish to ‘help’. One can imagine too, if we want to extend the metaphors of warfare here, that there is ample opportunity for people caught in the frame (say, neighbours or fellow protesters), to be hit by ‘friendly fire’ – harassed, arrested, killed – simply by having been caught in the ‘line of shooting’ of these activist’s cameras, and thus potentially targeted by hostile forces who have access to this footage by virtue of its sheer availability – the eagerness to be seen and shown (on the internet, on television, on free DVDs) means that the footage is readily available for many possible applications.

32 It all depends on who is watching the material and for what purpose.

I say this not to undermine the good work being done, but to refrain from over-valorising the role of Barrel POV in the service of NGOs and humanitarian projects (whether activist or documentary) with the ultimate goal, if that is indeed their goal, of toppling repressive regimes or dismantling unjust administrative structures. I don’t particularly want to join the ever-growing chorus of NGO-bashers who position themselves as more radical and more committed, while in the end justifying their right to do nothing in the face of massive injustice – precisely in fact, what Žižek proposes (2008: 180). I launch this critique as a kind of internal reckoning, an attempt to imagine how video activism might do more than flood the world with images that will likely never be watched, heroically and dramatically facing off camera to gun, getting caught up in the crossfire of individual micro-conflicts while, in effect and in actuality, the junta in Burma retrenches and the West Bank remains captive.

B’Tselem is a multi-million-dollar operation with a very slick and effective media team. They retain shared rights to the material shot in the territories and they edit it as they see fit.

33 Sometimes they package the shorts for national and/or international news, the package is even available complete with British-accented commentators. According to their publicity, they have a high degree of success placing their stories on news outlets such as BBC, CNN and Al Jazeera.

It is important to consider that B’Tselem as a whole is a project conceived and run by leftist Israelis, whose main aim as stated on their website is to ‘educate the Israeli public and policymakers about human rights violations in the Occupied Territories, combat the phenomenon of denial prevalent among the Israeli public, and help create a human rights culture in Israel.’

34 B’Tselem shows a kinder, more compassionate face of Israel – the very existence of the organisation, and the fact that their website and videos are not censored, goes some way to prove the ‘benevolence’ of the Israeli state. Yet despite its successes (in court, in the media, in fundraising), it surely cannot be said to have aided in the dismantling of a single settlement, let alone the now 45-year occupation (only a few years shorter than Burmese military rule), nor as suggested earlier, is that even one of its stated goals. Yet the Shooting Back project is considered so successful and has gained so much attention worldwide, that a new organisation called Videre, led by the first director of the Shooting Back project, has been set up to export the ‘video intervention model’ to other conflict zones, initially in South Africa and shortly thereafter, elsewhere. The Videre website states: ‘Realising the impact of the project, the head of Shooting Back joined forces with a reputable group of filmmakers, businessmen, lawyers and human rights activists to found Videre in 2008.’

35Which brings me to my final point, to do with the framing of the ‘raw’ material of these projects, transforming them into internationally disseminated productions. Both Burma VJ and Shooting Back take footage from ‘the field’, shot primarily by civilian activists in the line of fire, and contain and contextualise the material, framing it for an anticipated audience of concerned (or soon to be concerned) viewers. Anders Østergaard is now, due to the success of this film, a well known, award-winning Danish filmmaker. The likes of Dame Vivienne West-wood and Richard Gere lent their presence to Burma VJ’s European premieres. The film was sold to HBO, screened on BBC and other broadcast outlets around the world, had theatrical release in most major cities in the United States, and was nominated for an Academy Award in 2010. The UK-based Cooperative Bank even sponsored a campaign in conjunction with the UK release of the film to raise awareness about Burma. Surely this is good news.

Yet something is amiss. The model is too familiar. Of course the Burmese VJs could not risk exposing their identities to collaborate as named partners on the project, but they could surely have been listed as collaborators – even if only as DVB (Democratic Voice of Burma – an Oslo-based satellite broadcaster featured in the film) – and Østergaard could have been, say, the project coordinator, rather than the sole named director. Instead, their only credit is as camera people, anonymously and collectively credited as ‘The Burmese VJs’, a credit they share with the explicitly named Danish Director of Photography, Simon Plum. As it stands then, we’ve got the classic colonial model of the raw materials extracted at low cost, to the European video producer, yet at an extremely high human cost in terms of risk to the actual producers. It is then transformed, out of context, into a consumable good (that is, a well-worn generic story that Western viewers can comfortably consume), and that accrues cultural and presumably economic capital for the filmmaker, and hopefully some international attention paid to an urgent political crisis, perhaps concrete measures taken by governments and organisations in a position to make a difference, but essentially these come as biproducts of the film’s great success. In the film world, it is ultimately Østergaard who gets the acclaim; he is, in effect, the hero who brings the story to the all-important West’s attention.

B’Tselem’s project is not, or not primarily, an export, nor is it primarily conceived for the film world as a documentary. Yet the dynamic is not entirely dissimilar from that which we’ve seen in

Burma VJ, in that you have an Israeli-run organisation taking footage shot primarily by Palestinians under occupation, and although the stated intent is to improve the lives of those very Palestinians, you begin to see the benefits that accrue not to any individual Palestinian, let alone the whole population, but to the reputation of this organisation to the point of spawning predominantly Israeli-run off-shoot projects. What gets exported here is the know-how, the organisational acumen, the skills – all still firmly in the hands of Israeli occupiers, not Palestinians – not to mention the international image of the Israeli state as ultimately tolerant and benevolent in its willingness to allow public critique.

The aim of this intervention is to identify in the larger framing of these projects, the reproduction of systemic power relations and hierarchies of control that the micro-frame of the camera – shooting back – pretends or intends to deny. What we see in relation to the examples given here is that the potential does exist in these shoot-outs to undermine the power structures that be – using the weapon of mass communication – but it remains an empty threat as long as the operations of power are only exposed at the subjective level, neglecting or ignoring its systemic aspect, and worse, perpetuating structural relations of domination in their making.

The relationship between the camera and the gun is a provocative one, worth parsing in more detail that I am able to do justice to in this essay. Yet beyond the apparent framing and POV, which accounts for the thrills and the heroism associated with this sort of imagery, we must attend to the figurative framing to which this material is subjected if we are ever to understand the power relations as well as the subtending violences which these images may not only document but perhaps unwittingly reproduce. Shooting visual realist imagery in zones of conflict is never free of ideological implications, but it is a complicated operation to identify and distinguish between the intention and the effect, or if you will permit me to stretch the shooting metaphor one last time, the ‘target’ and the ‘impact’ of the material.

NOTES