In 2005, the Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa attended a special screening of his breakthrough horror film

Kairo (

Pulse, 2001) at the Japan Society in New York. The film was on the eve of a belated, limited theatrical release in the United States just ahead of its American remake. In his comments before and after the screening, Kurosawa located himself squarely within the resurgence of Japanese horror films beginning in the 1990s called ‘J-horror’, mentioning two of the phenomenon’s most successful examples, Hideo Nakata’s

Ringu (

Ring, 1998) and Takashi Shimizu’s

Ju-on (

The Grudge, 2003), as reference points. However, Kurosawa did not promise the audience that

Kairo would deliver more of the same in terms of J-horror expectations. Instead, he asked viewers to keep an open mind about what he called ‘the elasticity of the horror genre’, which he believed could accommodate even films like

Kairo.

1In this chapter, I will argue that Kurosawa’s remarkable exploration of the horror genre’s ‘elasticity’ can be framed through his articulations of violence as a matter of cinematic space structured by traumatic history. In contrast to much J-horror, Kurosawa prefers vast, empty spaces rather than the tight, claustrophobic spaces typified by

Ringu’s haunted well or

Ju-on’s cursed house. I have written elsewhere about J-horror’s doubled investments in the overlapping traumatic histories of World War II and the collapse of the Japanese bubble economy in the 1990s, but Kurosawa’s use of space opens up these histories to new forms of spectator address.

2 Kurosawa’s films encourage viewers to place themselves, both spatially and temporally, within traumatic histories they may not wish to see themselves as complicit with or responsible for.

Kurosawa (b. 1955) is an extraordinary and extraordinarily versatile director whose output over the last 25 years consists of much more than horror films, but even the breadth of his horror genre work alone is impossible to encompass in this essay.

3 His three most well-known horror films,

Cure (1997),

Kaira and

Sakebi (

Retribution, 2007), form something like a loose thematic trilogy organised by relations between space and violence; these relations, as I will explain, provide maps of communal responsibility for historical trauma. I will concentrate on

Sakebi, the latest and perhaps most ambitious entry in the trilogy, to illustrate how Kurosawa weaves together cinematic space and traumatic history.

Sakebi, which was written as well as directed by Kurosawa, is set in contemporary Tokyo. Yoshioka (Koji Yakusho), a tough police detective, investigates a mysterious series of murders in which victims are drowned in puddles of sea water. His work on the case draws him to an infamous sanitarium closed just after World War II, and to the ghost of a woman in a red dress (Riona Hazuki) who was tortured to death by being drowned in sea water at the sanitarium during the war. The ghost of this woman in red is behind the murders Yoshioka investigates – she has possessed certain ferry commuters who once passed by the ruins of the sanitarium on their way to work. These commuters then re-inflict the manner of her death on others. As Yoshioka delves deeper into the murders, he begins to feel that he is not just an investigator but also a prime suspect. After all, he took that ferry past the sanitarium himself, and he becomes less and less certain of what he remembers and forgets about the mysterious appearances and disappearances of his girlfriend Harue (Manami Konishi). Eventually, Yoshioka makes the shattering realisation that it was he who killed Harue in his apartment six months ago. So he is haunted not only by the woman in red, but by Harue’s ghost as well. The film’s enigmatic final shot shows Harue’s ghost crying a silent scream, wearing the clothes she was murdered in – a dress imprinted with red flowers that evoke the dress of the woman in red. Harue seems to cry out to Yoshioka, but the space that surrounds her is not the empty city streets Yoshioka walks through. Instead, she occupies the barren wasteland of an abandoned construction site by the sea where two of the murders took place and where the woman in red’s ghost has wandered throughout the film.

As striking as Harue’s gesture is in the final shot of

Sakebi, the blurred outlines of the landscape behind her may be even more important for charting how this film intertwines space and history. The three most important spaces of the film are Yoshioka’s apartment, the abandoned construction site, and the dilapidated sanitarium. These spaces orient spectators toward the initially rather puzzling temporal coordinates presented by the film.

Sakebi’s three key spaces correspond to various moments in time: the sanitarium is the repressed past of World War II; Yoshioka’s apartment is the repressed present of Harue’s murder; and the construction site is a crossroads between past, present and future. The identity of the construction site as a temporal crossroads is conveyed in a number of ways. It is land reclaimed from the sea that was planned, in pre-recessionary times, to be a condominium development. But now all construction is frozen, and the land is subject to earthquake tremors that cause puddles of sea water to emerge all over the site – puddles that become deadly when those possessed by the woman in red drown their victims in them. In other words, land reclaimed from the sea during an economic boom is now slipping back into the sea during an economic bust. In this sense, one temporality captured by the construction site is that of Japan since the recessionary 1990s, a time so traumatic for the nation’s concept of itself as an ever-expanding economic power that historians such as Harry Harootunian and Tomiko Yoda have called it ‘the long-deferred end of the postwar’ in Japan.

4

Fig. 1 Harue’s silent scream in the final shot of Sakebi (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2007).

But other temporalities course through the construction site as well: the woman in red’s appearances at the site evoke the past of World War II, with its traumatic legacies of military aggression, atomic victimhood and national defeat;

5 the current murders that occur at the site characterise the recessionary present; and the dream of what the site was going to be before the recession, the condominiums that never materialised, gesture toward a deferred future. The fact that these multiple temporalities are condensed within the single space of the construction site means that the site also functions as a setting for horrific conflicts over remembering and forgetting, history faced and history erased. The woman in red haunts the site so that others may remember her forgotten agony that dates back to World War II; Yoshioka returns to the site again and again to investigate the grisly murders while testing his own tortured memory about whether he may have committed them; Harue’s ghost seems trapped inside the site at the film’s end – she appears doomed to remain in a painful limbo between past, present and future.

The construction site dominates

Sakebi – it is where the film begins and ends, and it infects the other key spaces of Yoshioka’s apartment and the sanitarium. It is significant that this contamination between spaces is facilitated by water, as water is the primary sign of history in the film. Water as conquered force characterises those dreams of the future staked on the condominium development, while water as conquering force characterises the present economic realities when the recession paralyses that development. In addition, the waterways traversed by the ferry allow the past trauma of the World War II-era sanitarium to meet the present trauma of the murders. Water also carries connotations of pre-modernised historical time, since Tokyo’s pre-1868 past includes a long era when water was much more central to the city’s character than it is during the period from 1868 to today.

6 As the architectural historian Jinnai Hidenobu puts it, ‘it is all but forgotten today that Tokyo’s low city was once a city equal to Venice in its charms’. Today, Jinnai explains, ‘Tokyo’s unused canals have become no more than white elephants. They have come to belong to the ‘wrong’ side of the city, removed from human view and treated as shabby ‘parts of shame’ left behind in the wake of modernization.’

7 Or, as Kurosawa described it to me, ‘Tokyo was originally just part of the sea, a swamp. Since it is impossible to go back to that time, I decided [in

Sakebi] to draw a line to the past that began with World War II. Tokyo burned during World War II, and I wanted to show the city before and after the war, but it was so hard to do. The war was a key term for the film. I was trying to make a sort of map in the film from World War II to the present, but there are so many factors that change a city over time that it was hard to accomplish.’

8Kurosawa’s comment sheds light on how

Sakebi suggests links between Tokyo’s pre-modernised past as a water-centered city and the traumatic modernity of Tokyo’s destruction during World War II. But where Jinnai sees in Tokyo’s pre-modernised past a romantic rival to Venice, Kurosawa sees a city always on the apocalyptic verge of slipping back into the sea, an apocalypse nearly accomplished by other means during the catastrophic bombing of World War II. Another iteration in this series of Tokyo apocalypses is the Great Kant

ō Earthquake of 1923, an event Kurosawa evokes (perhaps alongside the Kobe Earthquake of 1995)

9 in

Sakebi by staging multiple earthquake tremors that unite all three of the film’s major spaces: Yoshioka’s apartment, the sanitarium and the construction site. In fact, it is the earthquake tremors that lead to the flooding of the construction site, that in turn facilitate the murders at the site, which are motivated by the death of the woman in red during World War II. This non-chronological yet simultaneously historical logic of recurring trauma is given shape in

Sakebi through a corresponding spatial logic, one where the film’s three major spaces provide viewers with a guide to Kurosawa’s ‘map in the film from World War II to the present’. But since Kurosawa’s map uses encroaching water and demolishing earthquakes to reference multiple historical coordinates,

Sakebi encourages viewers to imagine traumatic history beyond conventional cause/effect linearity, and space beyond boundaries dividing discrete locations. By making the film’s spaces into sites where history and horror converge, Kurosawa asks spectators to refigure their own relations to traumatic aspects of Japan’s past, present and future.

To gain a more specific sense of how Kurosawa accomplishes this form of spectator address through strategic deployments of space as signs of traumatic history, I would like to examine a particular moment from Sakebi. A sequence from roughly midway through the film begins with Yoshioka at the construction site, sitting alone. He has just experienced (imagined?) a terrifying encounter with the woman in red at the site – she spoke to him and insisted that it was Yoshioka who killed her all those years ago by drowning her in a puddle of sea water. He vehemently denies her accusation, for it makes no sense in terms of time. Yoshioka could not possibly have been at the sanitarium during World War II to commit the murder. But the accusation makes chilling sense in terms of space, and Kurosawa even inserts a few violent ‘fantasy’ images (Yoshioka’s imagination/ memory? The woman in red’s memory/suggestion?) depicting Yoshioka assaulting the woman in red at the sanitarium to underline this point. If the construction site is a crossroads between multiple temporalities, then the possibility arises of Yoshioka occupying a space where his direct but denied participation in Harue’s murder in the present can bleed into his indirect, even unconscious participation in the woman in red’s murder in the past.

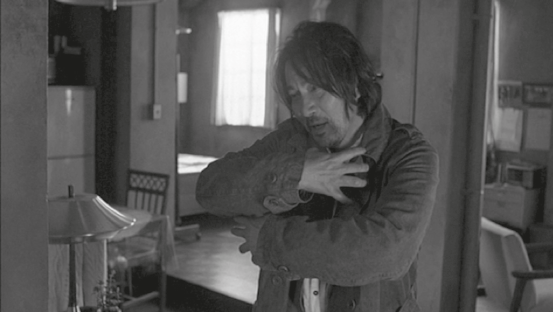

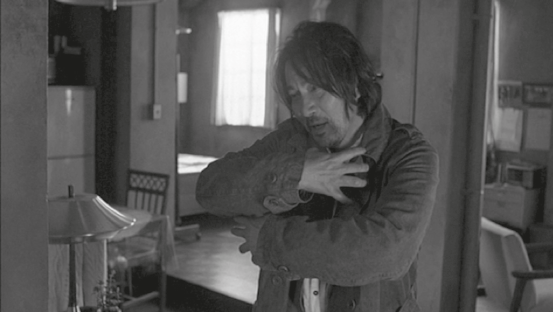

Throughout the sequence, Kurosawa emphasises this possibility of temporal contagion through spatial dynamics. The medium-shot of Yoshioka cradling his head, tortured over violent memories of the past and present he cannot fully own or disown, gives way to an extreme long shot with Yoshioka dwarfed in the far right corner of the frame. Yoshioka is no longer the centre of the viewer’s perceptual attention – he is secondary to the vast space that surrounds him. From background to foreground, that space is the modern urban vista of contemporary Tokyo; then the gray expanse of the sea (including a ship that catches Yoshioka’s eye, foreshadowing his later revelations about the commuter ferry and the sanitarium); then the brown mud of the construction site with its puddles of water indicating the sea’s infiltration of the land. Just as Yoshioka struggles to remember, so too does the open space function as an invitation for viewers to place themselves somewhere in this landscape that is also a time-scape, whether it be the present of the urban skyline, the past of the sea, or the contested past/present/ future of the construction site. Kurosawa’s address of the spectator through space can be detected through the relegation of Yoshioka to such a tiny and imbalanced area of the frame – the suggestion is that the spectator must balance the space, mark the time.

Fig. 2 Yoshioka dwarfed by the vast space that surrounds him.

This invitation to the viewer extends to the second half of the sequence, which transpires in Yoshioka’s apartment and involves a striking long take of a conversation between Yoshioka and Harue while they embrace each other tenderly. Yoshioka, like the audience, does not yet know that Harue is a ghost, but Kurosawa’s use of space as an entry into traumatic time encourages spectators to intuit this shocking fact. Kurosawa’s use of the long take, together with Yoshioka’s slow, measured delivery of the questions ‘What have I done a long time ago?’ and ‘What have I done lately?’ to Harue leaves viewers plenty of time to contemplate what these lines might mean for the film’s organisation of space as history. Is the violent threat of the construction site really so far away from this apparently cozy domestic scene? The similarities in colour between the brown wooden floor of Yoshioka’s apartment and the brown mud of the construction site, between the red flowers of Harue’s dress and the woman in red’s dress, coupled with the persistent sound of a faucet dripping inside the apartment to remind us of the potentially deadly puddles of sea water outside, make the two spaces more contiguous than discrete. The same goes for what at first seem like stark contrasts between the woman in red, with her frightening demand that Yoshioka remember his involvement in the past of her death, and Harue’s ghost, who comforts Yoshioka and encourages him to forget the past as an illusion irrelevant to their relationship. Yoshioka’s fetal-like collapse into Harue’s arms confirms how seductively regressive the lure of forgetting is, but Harue’s unnerving stare, accompanied as it is by a streak of red fabric that dominates the right side of the frame and a subtle reflected light on her face that suggest the ghostly presence of the woman in red, counteracts the possibility of forgetting. At the level of space, the woman in red and Harue’s ghost are doubles, not opposites. When Harue stares into the camera, she may be looking toward the woman in red offscreen, but since Kurosawa provides no reverse-shot to confirm this, her stare remains directed squarely at the spectator. And in that stare, we can barely miss Yoshioka’s questions rebounding back to us: ‘What have

you done a long time ago?’; ‘What have

you done lately?’

Kurosawa’s address of the spectator as complicit in violence, along the axes of space and time, can be elucidated further through Michel Foucault’s concept of a ‘heterotopia’. For Foucault, a heterotopia is a physical space that functions as a sort of cultural counter-site in which ‘all the other real sites that are found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested and inverted’. Examples of heterotopias include the cemetery and the cinema, two spaces that are ‘capable of juxtaposing in a single real space, several sites that are in themselves incompatible’. The cemetery simultaneously encompasses a sacred and immortal space, as well as a dark space associated with bodily illness and decay. The cinema is constructed on another apparent spatial impossibility: the projection of an illusory three-dimensional space in the cinematic image onto the two-dimensional space of the movie screen. Foucault distinguishes between a heterotopia of illusion, where a space is created that ‘exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory’, and a heterotopia of compensation, where the space created is ‘as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled’.

10

Fig. 3 The unnerving stare of Harue, directed toward the spectator’s relation to history.

Kurosawa’s heterotopic spaces of Yoshioka’s apartment, the sanitarium and the construction site are heterotopias of illusion. They each expose the illusion that the violence committed there is a unique event removed from any other space (similarities in the method of the murders and their watery surroundings collapse space) or any other time (ghostly connections unite World War II and contemporary recessionary Japan, as well as pre-modern and modern Japan). In fact, Foucault insists that ‘heterotopias are most often linked to slices of time – which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies. The heterotopia begins to function at its full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time.’ Once again, the cemetery provides an example of heterotopia as heterochrony: a space associated with both ‘the loss of life’ and life’s ‘quasi-eternity’, where signs of memorialised permanence take shape through ‘dissolution and disappearance’.

11 Focuault’s formulation of heterotopia as heterochrony in terms of an ‘absolute break with traditional time’ moves suggestively toward the disjunctive temporalities of historical trauma – events whose shattering impact exceed ‘pastness’ and infect the present. Following Foucault’s formulation illuminates how Kurosawa’s mapping of World War II onto the present works as a violent compression of space and time, as well as the stakes of that violence for spectatorship.

In

Sakebi, the sanitarium functions as the spatial centre for the traumatic history of World War II. Yoshioka learns of the sanitarium’s significance from an officer who identifies the building on an old, pre-World War II map. The officer tells Yoshioka about a rumour he heard that the inmates of the sanitarium were subjected to corporal punishment: their heads were dunked in washbowls full of sea water until they suffocated. Even though the sanitarium closed shortly after the war concluded, the officer notes that some of the inmates continued living there. When Yoshioka finally visits the ruined, rotting hulk of the sanitarium, he treads across partially flooded floors (again, water conjoins this space with others in the film) and discovers several markers of past habitation that function as traces of the woman in red. These include a half-empty washbowl, a weathered photograph of a woman with an infant in her arms, and a pile of human bones linked to a stain on a nearby wall that resembles the outlines of a human body. This stain bears a remarkable likeness to the ‘atomic shadows’ created when victims of the atomic blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were incinerated at such high temperatures that their bodies left nothing behind but scorched blots on the buildings or pavement next to them.

12

Fig. 4 The ghostly human stain that evokes ‘atomic shadows’.

This spectre of Japan’s victimisation during World War II is coupled with evidence of Japan’s role as wartime victimiser – the torture of the sanitarium inmates evokes some of the most painful revelations about Japanese wartime atrocities, including medical experiments performed on prisoners of war. Yoshioka sees the woman in red for the last time at the sanitarium, but her statement that she now forgives him proves misleading. She does not absolve him from the traumatic history of World War II she is embedded within as both human victim and ghostly victimiser, but dispels the blindness that has prevented Yoshioka from seeing his own complicity with that history. When Yoshioka returns home from the sanitarium, he faces Harue’s corpse for the first time and admits his guilt in her murder. When he combines Harue’s remains with those of the woman in red he recovers from the sanitarium, he acknowledges symbolically these mixed remains as one body – the violence of the past merges with the violence of the present, and Yoshioka finally recognises his responsibility for both.

Kurosawa’s decision to present Yoshioka as a murderer who deflects and then finally owns his responsibility for violence that traverses history already demands a lot from spectators who may be uncomfortable sharing an intimate connection with such a ‘compromised’ protagonist. But Kurosawa presses even harder on audience complicity by having Yoshioka’s fellow commuters on the ferry that passes the sanitarium in the early 1990s (the era of the recession’s beginning) come from such a broad cross-section of Japanese social life. Like Yoshioka, these commuters become possessed by the woman in red and commit murders that repeat her own drowning in sea water. In the process, they enact the philosopher George Santayana’s famous dictum that ‘those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’ as well as the structures of repetition common to traumatic experience – failure to absorb the trauma when it occurs results in its haunting recurrence in forms such as nightmares.

The commuters include Sakuma (Ikuji Nakamura), a doctor who murders his rebellious teenaged son whose last act is to ask his father for a large sum of money that he owes; Miyuki Yabe (Kaoru Okunuki), a female accountant who kills her company’s boss after he promises to leave his wife and legitimise his ongoing affair with Yabe; and Ichikawa (Ryo Tanaka), the boyfriend of another young woman in a red dress, Reiko Shibata (Sakiko Akiyoshi), whose parents must endure Ichikawa’s extortion of money from them after he murders her. The consistent theme of troubled economic transactions across all three of these murders foregrounds the recessionary context, while the relative randomness of the connections between the murderers highlights the complicity of all of Japan in their actions. As in so many other instances in Retribution, Kurosawa channels this invitation for audience self-recognition through space’s relation to time. The temporalities of World War Two and the recessionary 1990s commingle not only via the ferry that crosses water literally and time allegorically when it passes the sanitarium, but also through an actual and metaphorical mirror that is held up to the audience.

This mirror appears first during

Sakebi’s opening scene: the murder of Reiko Shibata at the construction site. In the first of the film’s long takes, the spectator witnesses Shibata’s drowning in a puddle of sea water, but our view of the murderer’s face is obscured by bright light reflecting off metal debris at the construction site. This visual motif of shimmering light reflected from a mirroring surface recurs throughout the film, always to announce a ghostly presence. It often appears in conjunction with a long take, as is the case here with Shibata’s murder and in the previously mentioned scene between Yoshioka and Harue’s ghost. The combination of mirrored light and the time provided by the long take for the audience to locate this light in space results in viewer awareness of the mirror on at least two levels. At the level of plot, the mirrored light signals the ghost’s presence and introduces uncertainty about what the viewer is seeing – for example, hiding the identity of the killer during Shibata’s murder. At the level of spectator address, the mirrored light encourages viewers to involve themselves in the film’s violence. The mirrored light may conceal the face of Shibata’s murderer, but since we do not see the source of this light, doesn’t the mirror direct that light back to us? Don’t we recognise ourselves on the other side of the mirror?

Fig. 5 A murder in which the killer’s identity is hidden by reflected light.

Kurosawa drives these questions home for the spectator by supplementing the mirrored light and long takes with actual mirrors. Yoshioka and Harue’s first interaction in his apartment is mediated by a full-length mirror, as is his encounter with the woman in red when she appears inside the same apartment; Sakuma’s interrogation at the police station (another long take) occurs in a room with two large mirrors, one of which reflects the ghostly bright light; Yabe studies her face in the mirror both before and after the murder she commits, with the woman in red appearing alongside her reflection in the second instance; Yoshioka’s visit to the sanitarium includes seeing his face reflected back to him in a broken mirror, providing a literalised image of his split subjectivity; and Yoshioka’s police partner touches his own reflection in a bowl of sea water prior to the arrival of the woman in red, who appears first as a reflection in the water and then as a flying ghost that drags the partner along with her when she ‘dives’ into the bowl of water from above. The proliferation of these mirrors, coupled with the visual motif of the woman in red appearing within the mirrors alongside the reflections of characters studying themselves, conveys an insistent theme realised in space: to look at yourself is to see the violence of the past and to recognise your place in it. Kurosawa’s strategic deployment of mirrors in cinematic space transforms this theme from one addressed solely to the characters inside the film to one directed equally toward the spectators outside it.

A startling switch point between the mirror as character address and spectator address occurs near the end of the film, when Yoshioka must face the fact that he murdered Harue. As Yoshioka desperately clings to the hope that he can somehow hold on to Harue even after realising he killed her – he promises her that ‘I know how to forget, it’s easy’ – Kurosawa inserts two shots in which we see Yoshioka embracing what he thinks to be Harue, but what is revealed to the viewer as empty space. In performing this revelation, Kurosawa transports the spectator to the other side of the mirror, the side where Yoshioka’s fantasies of Harue’s presence disintegrate alongside his impossible desire to forget about the traumatic past. Although the mirror in this instance is metaphorical (structured by shot/reverse-shot editing that alternates between Harue’s appearance and disappearance in Yoshioka’s arms) rather than an actual component of the mise-en-scène, its evocation of the mirrors littered throughout the film is unmistakable. Indeed, this final encounter between Yoshioka and Harue in his apartment recalls their original meeting in this space, when they look at each other for the first time – through their reflections in a mirror.

When Kurosawa deploys the mirror to collapse the distance between Yoshioka and the spectator, he supports Foucault’s understanding of the mirror as a heterotopic space. For Foucault, the mirror functions as a heterotopia because ‘it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy’.

13 Foucault describes this ‘counteraction’ as a self-recognition quite different from the idealised self-image of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s mirror stage, at least as Lacan tended to be mobilised in film theory of the 1970s. Laura Mulvey, for example, likens the Lacanian mirror stage to the experience of cinematic spectatorship in this way: ‘The sense of forgetting the world as the ego has subsequently come to perceive it (I forgot who I am and where I was) is nostalgically reminiscent of that presubjective moment [during the mirror stage] of image recognition.’

14 Compare Foucault on this point:

Fig. 6 Yoshioka’s face in a broken mirror, crystallizing his split subjectivity.

From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am.

15

Foucault’s emphasis on the mirror as a device for seeing oneself clearly, unsparingly, ‘there where I am’, captures Kurosawa’s insistence on heterotopic space as an inoculation against forgetting whether for character or spectator. We are a long way from Mulvey’s nostalgic cinematic mirror where the world is forgotten.

And yet

Sakebi, for all its commitment toward never forgetting the traumatic past, does seem to gesture toward forgiving by the film’s conclusion. Both the woman in red and Harue forgive Yoshioka for his sins in the past and the present. Still, Harue’s silent scream in the film’s final shot inevitably recalls the ear-splitting shrieks of the woman in red throughout the film. These shrieks, the sound of anguish that refuses to be contained by any conventional registers of time and space, reach out toward the spectator in ways perhaps more visceral than any image. Again, Kurosawa encourages the audience to fill in the woman in red’s voice for the silence of Harue. And what would that voice

say if its pain could be rendered in words?

Sakebi’s final image is Harue, a body with no voice. But the film’s final sounds belong to the woman in red, now a voice with no body. Three times, her voice-over intones, ‘I’m dead. Please, I wish everybody would die, too.’ On the final repetition, she completes only the first of the two sentences. So perhaps Harue’s silent scream might be translated as the missing words of the woman in red: ‘Please, I wish everybody would die, too.’ Death, in this sense, seems to encompass not so much forgiveness or forgetting as a desire for communal self-recognition – that everyone will know death through their shared responsibility to past, present, and future others.

Fig. 7 Yoshioka embraces only empty space, not Harue herself.

What I have described in this chapter as Kurosawa’s masterful manipulation of what he calls the ‘elasticity’ of the horror genre to forge connections between haunted space, traumatic history and complicit spectatorship began by noting his simultaneous proximity to and distance from the phenomenon of J-horror. So I will conclude by returning to where I began, with a brief speculation on what makes

Sakebi more ‘elastic’ in its use of horror than comparable J-horror efforts like

Ringu and

Ju-on. Ghosts, curses and the theme of revenge are essential to all three films, but

Sakebi departs from the other two by mapping space not in terms of traps that kill victims unlucky enough to step into them, but as a series of sites that offer victims and spectators alike opportunities for recognising links between horrors of the past and horrors of the present. The victims of

Ringu and

Ju-on die at the hands of angry ghosts seeking revenge for yesterday’s sins. The key victims in

Sakebi do not die themselves, but kill others as the ghostly woman in red was once killed. They must live with guilt and search for meaning, rather than suffer and die unknowing. The horror of

Sakebi is not the cat-and-mouse game of traps laying in wait, but the fear of loss attached to the fact that the spaces offering modes of understanding between present and past, responsibility and history, are always on the verge of disappearance. Perhaps this difference is what Kurosawa gestures toward when he states that his horror films are not particularly frightening.

16 And maybe they are not, at least not in the manner of the jolting, adrenalised terror generated by

Ringu and

Ju-on. But whatever Kurosawa’s films may ‘lack’ in the instant they make up for in sustained haunting – the kind of haunting that invites spectators to find themselves on the spatial maps he presents as guides to the violence of traumatic history.