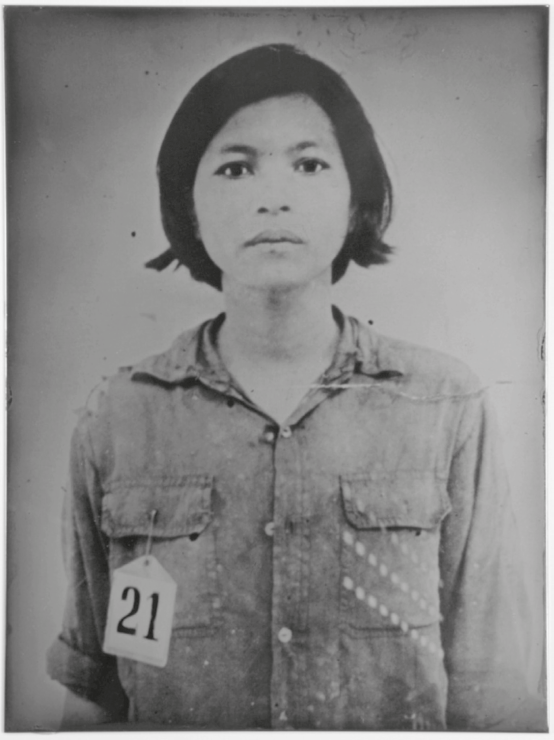

‘You, guy! What’s your name? What did you do during the Sihanouk regime? The Lon Nol regime?’ They’d already asked us these questions when we got off the truck. Why were they asking us again? Every prisoner was interrogated again and then it was my turn. Afterwards, I felt someone undoing my blindfolds. At first my eyes were out of focus but then my vision cleared. In front of me was a chair with a camera set across from it. ‘Go sit on that chair’, the guard said, pointing at me. The others handcuffed to me went with me but they sat on the floor as I was photographed. The guard took a picture of the front of my face, and then the side. Another guard measured my head and then they made an ID card. After me, they photographed the other people attached to me. Then they put our blindfolds back on.

1

The Vietnamese army reached Phnom Penh on 7 January 1979 after a two-week blitzkrieg in Cambodia. Their arrival in the capital city marked the end of Democratic Kampuchea, the regime established by the Khmer Rouge in April 1975. In less than four years, Pol Pot and his comrades had starved, worked to death and massacred hundreds of thousands of their fellow countrymen. While exploring the desolated streets of Phnom Penh on that day in January 1979, two Vietnamese photojournalists came across a barricaded high school. It was S-21 (the other name of Tuol Sleng), the prison where the

santebal (Khmer Rouge state security police) had jailed, tortured and executed about 14,000 Cambodians. Inside the buildings, the two men discovered several bodies, recently killed, and torture instruments. The walls were covered with blood.

2 There were also tens of thousands of pages of summaries, entrance forms, torture reports, signed execution orders, daily execution logs and confessions that the S-21 commander Kaing Guek Eav – better known as ‘Duch’ – and his staff had left when fleeing the city.

3Black-and-white mug shots of terrified men, women and children were attached to the confession files. The photography unit of Tuol Sleng took pictures of each inmate who was brought in. The first-hand account – quoted above – of the Cambodian artist Vann Nath, one of the few people who survived S-21, depicts the procedure that Nhem En, the Khmer Rouge in charge of the photography unit, and his colleagues followed.

4 The fact that many of the prisoners were actually high-ranking Khmer Rouge cadres arrested during purges explains why the prison personnel had to thoroughly record its criminal (Duch would have said ‘investigative’) activities. Industriousness was key to hunting interior enemies – a thriving business in the paranoid leading circles of Democratic Kampuchea. As proven by the archival fragments and remnants of physical structures scattered throughout the country,

5 Tuol Sleng was not the only Khmer Rouge interrogation/torture/execution centre, yet it is by far the most infamous – a sinister reputation it owes in part to these portraits.

S-21 was turned into the Tuol Sleng Museum for Genocidal Crimes in 1980 under the guidance of Mai Lam, a Vietnamese officer himself, and an expert in museology. The mug shots were put on permanent display in case Cambodians would recognise relatives, thereby helping identify the victims. It was only in the late 1990s that Western audiences became familiar with the pictures. In 1993, as the Kingdom of Cambodia had just been established following UN-monitored elections, two American photographers, Douglas Niven and Christopher Riley, found around six thousand original negatives in an old cabinet of Tuol Sleng. They set up the Archive Project Group with the aim of preserving and cataloguing them.

6 Twenty-two of these negatives were presented in an exhibition entitled ‘Facing Death: Portraits from Cambodia’s Killing Fields’, first shown in the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1997.

7 They were displayed in Gallery Three, next to rooms dedicated to the museum’s permanent photographic collection and a retrospective of American photography between 1890 and 1965. They had no labels and were loosely contextualised by a few paragraphs summarising, altogether, the history of Tuol Sleng, the discovery of the negatives by Niven and Riley, the production of the prints, and the funding of the Archive Project Group.

8 Such lack of information with regard to the history of the Khmer Rouge regime or the involvement of the United States in Cambodia subjected, according to the anthropologist Lindsay French, the photographs to two main kinds of readings. One was formal and aesthetic; the other was a ‘kind of heroic, allegorical’ reading. Turned into observers of suffering, visitors who wanted to escape such voyeuristic position had no choice but look at the pictures as conveying ‘something more abstract or general’, our condition of being human.

9 Since then, the mug shots have been globally circulated in various media and settings, from book covers to tourists’ blogs, and even to a Thai horror movie (

Ghost Game, Sarawut Wichiensarn, 2006), to such an extent that the anthropologist Rachel Hughes, conducting interviews with Western tourists at the Tuol Sleng Museum in 2000, stressed ‘the significant number of tourists who professed a familiarity with the S-21 prisoner photographs’.

10 Once scrutinised in utmost secrecy, since Duch handed over the confession files only to a restricted number of Khmer Rouge leaders (mainly Pol Pot and Nuon Chea), the black-and-white portraits can now be seen worldwide. It is this administrative record of extermination, the very symbol of Khmer Rouge’s absolute power, which has become the icon of the Cambodian Genocide.

Fig. 1 View of Tuol Sleng, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Photograph by W. Noud. 17 (Creative Commons)

Over the past ten years several artists, Cambodians and non-Cambodians alike, have created pieces incorporating the Tuol Sleng mug shots. Appropriating such a specific kind of photograph into artworks raises a number of issues. Are they not, first and foremost, evidence of the crimes perpetrated at S-21? It bears recalling that some of the pictures had been shown during Duch’s trial at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia in 2009. The particular context offered by art settings for looking at such images makes it compelling to ask to which extent aestheticisation affects the evidential status of these images. It is a recurring issue in discussions on artistic representation of mass atrocity. In her analysis of beauty and the sublime in Holocaust-related artworks, Janet Wolff underscores the risk that ‘visual pleasure negates horror by aestheticizing violence and atrocity, by proposing redemption in the face of outrage or by providing consolation in the encounter with beauty’.

11 Her concern resounds all the more strongly when related to what Riley and Niven declared in an 1997 interview in the

Village Voice regarding their selection of pictures for the exhibition ‘Facing Death: Portraits from Cambodia’s Killing Fields’: ‘Even though they were of horrible subject matter, with horrible stories, we saw the possibility of making beautiful photographs.’

12However, one cannot but acknowledge that the evidential status of the mug shots has already been seriously undermined as their reception in widening geographic and cultural circles charged them with new meanings. Captions on blogs or comments in television news stories make this clear: S-21 photographs have been turned into emotional portraiture, icons of atrocity and injustice that make us feel and even project ourselves into such suffering. This transformation, obscuring the reality of Tuol Sleng (for example, the actual identity of the victims, or procedures of control) has far-reaching historiographic consequences. It impacts on forms of remembrance and identity politics. Indeed, of all the issues raised, the fact that our empathy for the victims stems from portraits made by their very murderers is not the least puzzling. Against such a backdrop, artistic remediation might well help to clarify the processes (and traps) of emotional commodification and shed light on the cultural construction of our gaze when facing such photographs.

The notion of ‘genocidal images’, coined by the art critic Thierry de Duve in an article discussing the exhibition

S-21 by Christian Caujolle (founder of the photo agency VU) within the framework of the 1997 Rencontres Photographiques d’Arles, proves most relevant to such discussion. De Duve argues that images produced by perpetrators are generally considered in terms of ethics and politics: they are de-aestheticised in the contexts of ‘duty of memory’.

13 With the notion of ‘genocidal images’ he aims to open up an aesthetic perception of such pictures because ‘calling the photographs the name of art … is just one way, the clumsiest certainly, of making sure that the people on the photographs are restored to their humanity’.

14 The way such a category is reflected upon by artists who have appropriated Tuol Sleng mug shots is what this chapter analyses in relation to the following artworks:

The Texture of Memory, by Dinh Q Lê (2000–01);

Messengers, by Ly Daravuth (2001);

88 out of 14,000, by Alice Miceli (2004);

In the Eclipse of Angkor: Tuol Sleng, Choeung Ek, and Khmer Temples, by Binh Danh (2008); and

Discovering the Other: Tuol Sleng – After All Who Rewrites History Better Than You, by Despina Meimaroglou (2008).

Genocidal images present artists and spectators with a painful challenge. Are we able to escape what Holocaust scholar Marianne Hirsch defines as ‘the monocular seeing that conflates the camera with a weapon’? ‘Unbearably’, Hirsch argues, ‘the viewer is positioned in the place identical with that of the weapon of destruction: our look, like the photographer’s, is in the place of the executioner.’

15 Regaining another form of bearing witness and deconstructing the perpetrator’s aesthetics and ideology, which still impregnate these images – in other words: restoring the victims’ humanity – are thus core issues in the artworks concerned.

The artists resort to two kinds of strategy, often combined, to counter Hirsch’s ‘monocular seeing’ and produce – to quote Ulrich Baer – ‘corrective captions’ for the mug shots. Presentational strategies that aim to modify the viewer’s position, thereby making it possible ‘to re-see images of victimhood from positions that break with the photographer’s perspective of mastery’,

16 and material strategies that reconstruct the narratives associated with the mug shots by creating ‘very different embodied experiences of images and very different affective tones or theatres of consumption’ through addition and medial intervention.

17 For each of the five artists, these strategies mean bringing the spectator into interaction with the image and initiating active forms of reception. Watching the mug shots is no longer a voyeuristic act framed by the perpetrator’s gaze. It becomes a gesture of respect toward the victims, their memory, and toward history, too, as the spectator engages in critically viewing the images ‘instead of responding to them ritualistically with fear, outrage, or pity’.

18 Dinh Q Lê’s

The Texture of Memory (the eponymous title refers to James Young’s book on Holocaust monuments and memorials) is a series of portraits of Tuol Sleng prisoners. It is not the first work in which the artist remediates the mug shots. His 1998 piece

Cambodia: Splendor and Darkness merges them with images of Angkor Wat’s wall carvings through a process of photo-weaving, thereby underlining cultural connections between the Temple of Angkor and the Cambodian tragedy, the human cost of the construction of the Temple echoing Pol Pot’s references to the glorious Angkor era. To manufacture

The Texture of Memory Lê worked with women from Ho Chi Minh City. He drew sketches of several portraits; the outlines were then embroidered by the women on thick white cotton, white threads on white sheets stretched over a bamboo frame like a painting. The artist states that it is a little hard to see until you are near, then the portraits emerge. Viewers are encouraged to touch these portraits, like reading Braille: ‘I hope over the years the viewers’ touch will stain the embroidery and make the portraits more visible. Like the carvings at Angkor, where the more people touch, the shinier it gets and the more visible it becomes. In a way, the more people who participate, the more these memories will become alive.’

19 Blindness appears as a paradigm for traumatic memory in Lê’s work. It is displayed at several levels: the blindfolded prisoners brought to the Tuol Sleng photography unit; the nature of the Khmer Rouge regime itself, secretive and conspirational, keeping the Cambodian population in the dark while it was watching everything (‘The

Angkar – the Organization – has the eyes of the pineapple’, the infamous slogan went); and the story, mentioned by the artist, of Cambodian women survivors who resettled in Long Beach, California in 1982, who had all witnessed the execution of their husband and/or their children, and, traumatised by what they had seen, suffered from ‘hysterical blindness’.

20Sight proves to be an unreliable, impaired and misleading sense when it comes to remembering such atrocities. It must therefore be supplemented, even replaced, by another one – that of touch. The passage from scopic to haptic as performed in

The Texture of Memory materialises in most concrete terms Jill Bennett’s notion of ‘sense memory’.

21 The latter, Bennett writes, is ‘not so much

speaking of but

speaking out of a particular memory or experience – in other words speaking from the body

sustaining sensation’.

22 As the spectator’s fingers run over the embroidered threads, the picture in turn touches ‘the viewer who feels rather than simply sees the event and is drawn into the image through a process of affective contagion’.

23 It is how sense memory de-familiarises the iconic and re-affects people who have become so familiar with images that they no longer see them. The portraits forming

The Texture of Memory are ‘productive’ rather than ‘representational’ images.

Making the act of looking a transformative memory experience is also central to the work of Binh Danh. In In the Eclipse of Angkor: Tuol Sleng, Choeung Ek, and Khmer Temples, the artist mingles daguerreotypes of Tuol Sleng victims with daguerreotypes of his own photographs of contemporary Buddhist monks and ancient Cambodian temples. It is not the first time, either, that Danh deals with the mug shots and develops complex photography techniques for re-presenting them. Danh has a conception similar to that of Lê regarding the active engagement of the viewer in making memories alive. In In the Eclipse of Angkor the spectator cannot identify the images from afar because the daguerreotypes look like framed silver mirrors. Thus, the viewer must get closer and stand in front of them so that the negative image of the daguerreotype reflects her silhouette and turns positive, visible.

In the Eclipse of Angkor fuses different kinds of image: afterimage, an image that both remains on the retina and shapes our mediated experience of traumatic memory, trace and icon.

24 Ghost-image: a remnant, a partially recorded picture. The idea of the ghost takes on further signification in the context of Buddhism. Cambodians believe that the ghosts of suffering victims still haunt places, especially where no proper burial has been conducted such as killing fields and memorials. It is this haunting presence that the image captures. Latent image: the not-yet-visible image waiting for both the artist’s creative gesture (exposing the silver plate) and the viewer’s movement. Afterimage, ghost image, latent image express the limits of traumatic memory: fragmented, incomplete, vanishing and shaped by the outside.

Fig. 2 Binh Danh, Skulls of Choeung Ek, 2008, daguerreotype, 45 x 60 cm, Eleanor D. Wilson Museum, Hollins University, VA, USA. Courtesy the artist.

As the spectator stands in front of the daguerreotype, she is captured, merged with the victim in the same frame, the same time – neither past nor present – and the same space. The idea that viewers might literally and physically reveal the dead and that remembering means making victims ‘alive’ again was already an integral part of

Ancestral Altars (2006), an earlier series of Danh’s dedicated to S-21 inmates which was based on his own chlorophyll printing method:

25

They [the victims] all have stories to tell and are asking the same question as they peer out to the viewer: How could this happen? I wanted to give these portraits voices so they can teach us … I hope they will be alive in us as we remember them and in return we give them life.

26

This conception is anchored by Danh’s Buddhist beliefs. There is a cycle of life in which we all take part and have to fulfill some task, which is another way to say that each of us is responsible for the memory of the victims: ‘The portraits become the spectators, holding us accountable for the genocide that took place.’

27 Moreover, it is a reciprocal movement. While ‘the identity recorded in the photograph is extended and enhanced, revealing a form of inner self’,

28 the daguerreo-type image becomes visible and another side of the viewer’s identity is revealed in the process. This victim, the reflection seems to imply, could be you if you had lived in another epoch and place; in that sense the portrait is a reminder that such events might happen at any time, ensnaring those who least expect them to.

Fig. 3 Binh Danh, Ghost of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum # 2, 2008, daguerreotype, 30 x 24 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The works of Binh Danh and Dinh Q Lê deny the spectator the possibility of merely glancing at the mug shots. By integrating time and duration into the processes of both making and looking at the works, the two artists undo the gaze of the perpetrator. When Nhem En and his colleagues photographed the inmates one after another, at a fast pace, they hardly looked at them. The prisoners were mere objects, deprived of individuality. Nhem En said in an interview that within a short time he no longer felt anything when photographing incoming prisoners. As he was caught in the desensitising routine of Tuol Sleng: ‘it became normal, like feeling numb’.

29 This is no surprise considering the psychological mechanisms at play in situations of mass violence. Taking pictures supplies the perpetrator with a protective shield. Victims are objectified and circumscribed within the unreality of the camera screen. In other terms, de-humanised.

According to the historian Bernd Hüppauf, such de-humanisation marks a continuity between images produced by modern technology and the scopic regime that was developed during World War II, which he describes as the

Mutation of the abstraction and emptiness of the fascist version… [T]echnology … makes it possible for the distanced and cool gaze to watch how advanced techniques of destruction transform living beings into elements of electronically manipulated games of violence. […] Images of dying and killing produced by advanced technology are sufficiently empty to be forgotten.

30

The constellation formed by technology, violence and modernity (which has been analysed by Zygmunt Baumann for example)

31 explains why Lê and Danh resort to, respectively, traditional crafts (weaving) and old photographic techniques (daguerreotype) for dealing with the mug shots. Both ‘neutralise’ a technology that has at times served heinous objectives.

Is there a possibility of reclaiming technology against de-humanisation when it comes to genocidal images? It seems so, as 88 out of 14,000, the video work by Brazilian artist Alice Miceli, demonstrates. In Tuol Sleng, the artist selected the portraits of inmates for whom the dates of both arrest and execution were available: 88 people. She projected the portraits onto a black space, chronologically, onto falling sand. One day of survival means one kilogram of sand, or four seconds of visibility. In her video, Miceli reverses the objectification inherent in the act of picture-taking.

Fig. 4 Alice Miceli, 88 out of 14,000, 2004, exhibition view, Phoenix Halle

(Re)-shooting becomes a means of rescue as the artist injects life (the life of the prisoner) into the document: more than blurring the distinction between life and death,

88 out of 14,000 points out the danger that lies in looking at the mug shots as icons of death only. In doing so, Miceli emphasises the period that comes after the moment of shooting, beyond the static vision of the photograph and the photographer, because things did not stop on the chair in front of En’s camera. The mug shot, although it is the last image we can see of the prisoners alive, was for the victims only a prelude to days or weeks of suffering, of being chained, starved and tortured. However fragile and near to their end, these are lives that are represented via the contracted temporality of

88 out of 14,000: people who demand that we think about what they endured. By proposing such movement – or allusion thereof – Miceli unfreezes Tuol Sleng’s ‘instances of humiliation’.

32In Discovering the Other: Tuol Sleng – After All Who Rewrites History Better Than You, the Greek artist Despina Meimaroglou shows similar concerns. The installation is comprised of two parts. The first part is a replica of a cell in Tuol Sleng, realised by the film and stage designer Lorie Marks on the basis of pictures Meimaroglou had taken in the museum.

The photographs on the walls are pictures from the book she published in 2005 following her travels in Southeast Asia. Meimaroglou describes her experience in Tuol Sleng Museum, when she entered the cells as overwhelming to the point of physical pain. The idea of re-creating one of the cells in the exhibition space (the Contemporary Art Centre of Thessaloniki) was born out of her observation that ‘most of my fellow travellers [visiting Tuol Sleng] refused to come along because they wanted to avoid the discomfort’.

33 With the replica, the artist wants to force the viewer to enter the room, to feel as uneasy and distressed as she felt then.

The reconstructed cell constitutes the entry point to the second part of the installation, ‘Me Instead of Them’, a series of five ‘portraits’. Meimaroglou scanned five different people and printed each head in life-size on a paper bag. After putting the bag on her head – blindfolded as the victims were just before being photographed – the artist tries to imagine a position reflecting the facial expression of each individual and to reproduce it with her own body. By vicariously experiencing the physical visit of the museum, the spectator finds herself involved in the process of remembrance, accessing the victims through the body of the artist. In this process, the viewer is no longer a passive recipient of Meimaroglou’s interpretation, but takes part in the transmission of memory.

Discovering the Other: Tuol Sleng – After All Who Rewrites History Better Than You offers an additional approach towards the notion of ‘sense memory’. In Meimaroglou’s installation, the bodily experience of sustaining sensation is that of the physical encounter with the mug shots as artefact and as evidential document. In that sense, the artist opens up a reflection on the infrastructures – in this case the museum – through which the memory of the Cambodian genocide is represented and conveyed. At the same time, the installation encourages the viewer to look beyond the memorial display and think about the feelings of the inmates at the moment they were photographed. In other words, to replace the dead face of the mug shot with that of the individual, terrified but somehow alive.

Fig. 5 Alice Miceli, 88 out of 14,000, 2004, exhibition view, Phoenix Halle.

Fig. 6 Despina Meimaroglou, Discovering the Other: Tuol Sleng – After All Who Rewrites History Better Than You, 2008, multimedia, in collaboration with Lori Marks, 350 x 250 cm, National Museum of Contemporary Art of Thessaloniki, Greece. Courtesy of the artist.

The ways in which forms of mediation affect the politics of remembrance and identity politics is at the core of Ly Daravuth’s work.

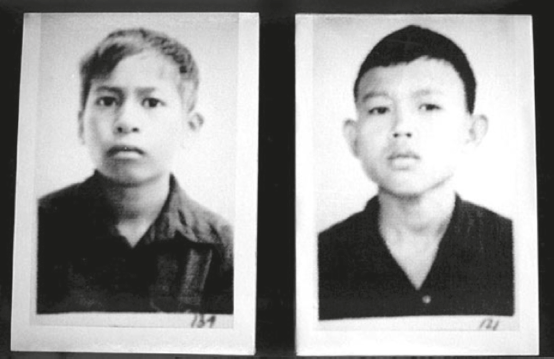

34 Messengers was presented for the first time in 2000 in Phnom Penh in a show entitled ‘The Legacy of Absence: A Cambodian Story’ (which he co-curated with Ingrid Muan). Ly’s installation brings altogether portraits of children of present-day Cambodia and ‘messengers’, children who carried messages to Khmer Rouge cadres. The photographs are manipulated so that they all mimic Tuol Sleng mug shots, the more recent pictures having been deteriorated through various artificial means. Khmer Rouge songs play in the background.

35In

Messengers Ly and Muan underscore that the installation questions the mechanisms at play in the interpretation of historical and evidential documents, namely, the context of their presentation. What are the preconceptions of the viewers? And what is the role of visual encoding in shaping interpretations? Ly states that

Fig. 7 Despina Meimaroglou, Me Instead of Them, 2008, photograph, 120 x 80 cm, National Museum of Contemporary Art of Thessaloniki, Greece. Courtesy the artist.

Because of the blurred black and white format and the numbering of each child, we tend to read these photographs first as images of victims, when they are ‘really’ messengers and thus people who actively served the Pol Pot regime. The fact that upon seeing their faces, I immediately thought of victims, made me uneasy. My installation wishes to question what is a document? What is ‘the truth’? And what is the relationship between the two?

36

The ‘immediate recognition of victimhood’

37 that Ly tries to interrupt with

Messengers raises the issue of narrative and memory tools that have been given to Cambodians for building their post-Khmer Rouge identity, and the role that Tuol Sleng as a memorial/museum institution has played in that context.

Commenting on the museum which S-21 had become in 1980, the French journalist and researcher Serge Thion stresses that:

the masters of the new Cambodian regime, in early 1979, commissioned some Vietnamese experts, trained in Poland, to refurbish the interrogation centre called Tuol Sleng [in order to] attract part of the sinister charisma of Auschwitz.

38

Fig. 8 Ly Daravuth, Messengers, 2001, photography, Reyum Gallery, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Courtesy of the artist.

Why posit such a connection? The Vietnamese had obvious reasons for linking the Cambodian tragedy to the Holocaust, and presenting the Khmer Rouge as a fascist rather than a communist regime – a far more acceptable version of events, one which made it superfluous for Cambodians to ponder for too long the relationship between, on the one hand the ‘Pol Pot and Ieng Sary’ clique, and on the other the new Vietnamese-sponsored government (composed of former Khmer Rouge who had defected as late as 1978) and the Vietnamese

tout court who had supported the Communist Party of Kampuchea for many years.

Moreover, the international community, considering the new leaders of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea as nothing but a puppet government, blamed Vietnam for its occupation of Cambodia. There were both humanitarian and economic consequences (not to mention the fact the Khmer Rouge retained for years their seat at the UN as the actual representative of Cambodia!). The Vietnamese had to justify their presence in Cambodia by tugging at the heartstrings of European and American leaders and by soliciting public opinion to attract Western sympathy. Consequently, the official version of events cast the Cambodians as victims of a fascist clique that had perverted communist ideals; as a result, the forms of memory made available to Khmers in Tuol Sleng Museum were shaped by both Vietnamese ideological interpretations and Western representations of mass atrocity and mourning. Ly recounts that during the exhibition local visitors asked him whether they could make CDs from the Khmer Rouge songs playing in the background to take them home. Nostalgia? For Ly and Muan, the installation, because of its ambiguity, allowed some visitors ‘to begin to care to recast themselves as, perhaps, former Khmer Rouge’.

39 Messengers conveys a ‘grey zones’-riddled picture of Democratic Kampuchea and its poisonous legacy. By underlining the uses and abuses of memory in Cambodian society (so well epitomised by the Tuol Sleng photographs) the artist stresses the danger of collective victimhood for the Cambodians. How can there be any social healing if everyone claims to be a victim of the Khmer Rouge and escapes liability? To such a question,

Messengers answers that the mug shots might play a significant role in reconciliation and truth finding and provide the Cambodian society with keys for self-reflection on condition that all levels of complexity making up the history of Democratic Kampuchea and its aftermath are represented.

It is a process in which contemporary art might be a chosen actor. The range of aesthetic treatments and interpretations in the works of Ly Daravuth, Dinh Q Lê, Alice Miceli, Despina Meimaroglou and Binh Danh show that genocidal images are to be assessed in a continuing process of production, exchange, usage and meaning. As Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart so aptly put it: photographs ‘are enmeshed in, and active in, social relations, not merely passive entities in this process’: changes of ownership, physical location and relationships are ascribed to photographs.

40 Genocidal images are thus reconfigured through a long chain of remediation and transformation, integrated within multiple social realms of remembrance, resounding in other contexts, signifying differently, sometimes at the expense of their original meaning. These are complex processes in which affect and understanding – emotional and epistemic regimes – combine and merge. Both sides operate together to produce ‘a dynamic encounter with a structure of representation’ and to put ‘an outside and an inside into contact’.

41 It is through such encounters that genocidal images can reverberate at many levels (cultural, psychological, political, historical) and in widening circles: it is how they contribute as an aesthetic category to deepening knowledge of the criminal events (and their perpetrators). They clarify the role visualisation plays in the context of political terror and atrocity on the one hand; and reconciliation, healing and commemoration on the other.

And yet… In April 2009, Nhem En, the chief photographer of Tuol Sleng, announced that he was putting the camera he used in S-21 (with a pair of sandals that belonged to Pol Pot) for auction for a price of half a million dollars.

42NOTES

The author and editors are grateful to Rebus Journal for allowing the chapter to be re-printed