The evening breeze was gentle. The crescent moon crept behind the clouds like a thief terrified of being caught. The air grew colder, unaware of our burning spirits. Our sweat ran hot, our faces flush. We had asked Dormin to drive us to the execution site. […] The car sped to Sialangbuah to pick up our quota. Who knows why, but we feared nothing. Dormin was a real James Bond, racing down the potholed road. Perhaps he was daydreaming, imagining Japanese beheading allied soldiers like in some old WWII movie, and not looking at the road in front of him. We walked the last hundred yards, making our way through undergrowth and oil palm. Under the gleam of flashlights, we arrived at an old well. One by one, Karlub, Uyung and Simin beheaded the five goats.

–

Embun Berdarah (‘Dew of Blood’), Amir Hasan Nasution

1

HISTORY: SCENE AND OBSCENE

On the night of 30 September 1965, six of Indonesia’s top army generals were abducted and murdered in an abortive coup attempt. Who was ultimately behind this operation, and their final objectives, remains unclear.

2 In a response that appears to have been remarkably well rehearsed, General Suharto seized control of the armed forces and instigated a series of nationwide purges to consolidate his power. Suharto engineered and set in motion a killing machine whose chain of command reached into every region and every village, murdering alleged communists, trade unionists, organised peasants, members of the women’s movement and anybody else the army considered a threat.

3The campaign was deliberately organised so as to implicate the ‘masses’ (or

massa, the term used by Indonesian officials when reference to the massacres is unavoidable): much of the killing, although under the supervision of the army, was actually carried out by paramilitary branches of political groups opposed to the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, or PKI) and affiliated groups. As the pro-Suharto American diplomat Paul F. Gardner observes, Surharto ‘did not wish to involve the army directly … he preferred instead [quoting Surharto], “to assist the people to protect themselves and to cleanse their individual areas of this evil seed [the PKI].”’

4 This ‘cleansing’ cleared the political stage for the creation of the ‘New Order’ military dictatorship.

The massacres that swept the archipelago in the months after October 1965 were one of the most systematic genocides of the twentieth century. To the extent that the genocidaires remain largely in power, its national (and to a significant degree, international) account has been given by its victors.

The rendering of this account, however, has not been a project of straightforward revisionist erasure. While there have been no memorials for genocide victims, and no trials for their killers, the official histories of the New Order do not simply deny its constitutive violence: ever since the killings, the Indonesian government has worn the face of that violence, as administrators and agents of genocide were promoted through the ranks of military and government.

5 The violence of the massacres continued, and those who instigated it still seek to conjure its force in ways that we will analyse here.

Yet the official history (and this is no surprise) refuses to recollect the systematic nature of the terror within a judicial, ethical or forensic frame. The deliberate nature of the massacres is

obscene to an official history, which casts the extermination programme as the spontaneous uprising of a people united in a heroic struggle against the ‘evil seed’ of atheist communism.

6 Wherever this historical scenario is rehearsed – in the official history books or statue books; in classrooms or national parades; in propaganda films or the rallies of paramilitary groups; in the management and labour structures of the plantations or, until recently, the stipulations determining the status of identity cards – its obscenity operates, insinuating terror, haunting the available spaces of social interaction.

The apparatus, activities and artefacts of movie-making provide the means and methods of research for the project upon which this chapter reflects. As cinema has been both a means of research and an object of it, a rehearsal of the New Order history that bears particular mention here is the four-hour propaganda film

The Treachery of the September 30th Movement of the Indonesian Communist Party [

Pengkhianatan G 30 S/PKI] (dir. Noer, 1984). The film was mandatory viewing every year for twenty-four years on Indonesian television and in all cinemas until Suharto resigned in 1998. Schools would visit the cinema, and families were compelled to watch the film on TV. These thousands of screenings surely constitute the most potent performance of the official history of 1965–66. As such,

G30S is marked by (or marks) the generic imperatives, stylistic tendencies and performative routines and effects of the New Order history. It is precisely these imperatives, tendencies and effects that this chapter focuses on.

7The film restages the night of 30 September 1965 as a curious blend of documentary exposé, political thriller and slasher movie. It opens and closes as sensational reportage (black-and-white archival footage and photographs; shots of documents and newspaper clippings; a mastering narration over dramatic music) while the requirements of a thriller narrative are fulfilled through a plot performed by shadowy enemies of state, here played by treasonous PKI villains. The slasher aesthetic renders the graphic murder of the six generals at the hands of a communist mob, their genitals mutilated in a sadomasochistic orgy perpetrated by members of the PKI-affiliated Gerwani (Women’s Movement), burnt with cigarettes, slashed with razor blades, stabbed with bayonets, beaten with rifle butts, all to the accompaniment of wild chanting and drums.

The exposé and the slasher are both forms predicated on an explicit and excessive visibility. In the exposé this takes the form of an insistence on the self-evidence of its images (‘it is plain to see how things really were and this is plainly how things were’). The excess of the slasher, insists that we see everything, revelling in the generic gore of a projected PKI sadism. This grotesque excess operates in interesting ways. It is not merely designed to elicit a common outrage for the PKI, but to create a scene of sacrificial and ritual participation. And, as spectacle, the violence fascinates. Thus are spectators bound and incorporated by an enthrallment with their projected enemy. In as much as the PKI violence is clearly displaced (and projected) state violence, should one identify sympathetically with the massacres’ victims, that violence would immediately become a threat.

These genres serve the New Order ‘historiography’ well, staging the PKI as both self-evidently and explicitly sadistic, while, as the political thriller’s necessarily shadowy villains, also threateningly spectral (and spectral not least because, by the time of the film’s production, the PKI had been exterminated). For all its excessively visible violence, the film withholds from view the true force of the violence which it performs – that of the massacres.

The film is so potent because it serves to justify a massacre that remains obscene, or inadmissible, within the framework of the narrative. The film

generically rehearses the killing of six generals, a general’s daughter, and the same general’s adjutant. The rehearsal is generic not only because of its respect for cinematic codes and conventions, but also its faithfulness to a twenty-year-old official history that those codes serve. That is to say this scene, the murder of the generals, is received as

the legitimating metonym for the massacres that followed.

The subsequent murder of at least half a million people goes unmentioned, and yet it is this unspoken terror that provides the film with a certain mystique, a

frisson and fascination.

8 For the massacres hardly fail to haunt

G30S, because the film exists almost wholly to justify the massacres and the regime founded upon them. The film’s generic rehearsals derive their conventionality precisely from their social and political context – a context constituted by genocide; the film is able to perform the genocide without directly citing it, then, because the genocide is the violence that continues to constitute the film’s iterative condition. Thus the film conjures a violence as

spectre – the extermination of the entire PKI (a group itself rendered spectral) – by not mentioning it explicitly. It is in this way that

G30S is a

performative instrument of terror – it does violence.

G30S was, perhaps more than any other piece of propaganda, the basis for the second half of Suharto’s rule.

The film graphically demonstrates the way in which New Order history at once conjures the PKI as a spectral power and condenses that power in spectacular images of violence, so as to claim that power for the shadowy techniques of state terror. The spectral subsists in the spectacle. Obscene to the staging of national history, the systematic nature of the violence nevertheless sets the scene, lurking in the wings and constantly threatening a spectacular (re)appearance. It is a haunting presence that might flare up again in a show of force through which the nation has been compelled to imagine and perform itself.

Researchers of New Order histories will find a generic coherence to its scripts and performances (such as one finds in G30S – no transgressive formal experiments there), but clearly the aim of these ‘historiographic’ conventions is not historical coherence as such since they are not concerned with adequacy to actual events. New Order historiography is not a history in the realist register. It is not recounted in order to refer; rather, it is rehearsed in order to exercise a power. It is a history in the performative register: history as a histrionics of terror.

Michael Taussig, writing of the economy of violence in the Amazonian rubber boom of the late nineteenth century, describes ‘

the mediation of terror through narration, and the problem that raises for effective counter-representations’.

9 This chapter and the film project it reflects upon attempt to make headway in analysing this problematic even as it re-casts its epistemology.

Eschewing an epistemology of representation, we avoid considering historical narration as mediation of a past that can be made coherently and fully present; instead we consider historical narrative as a performance whose staging produces effects. It is these historical and contemporary effects that are our primary concern here. We analyse how the elaborations and ellipses of the ceaselessly rehearsed histories of the period conjure terror and interact with the conjurations of previous acts – whether acts of historical account (speech acts) or historical acts (the events that constitute the past).

10 It is less a matter of producing effective counter-

representations than intervening with counter-

performances, that is, interventions capable of countering the spectral powers of history as terror.

This chapter sketches out some critical moments from the early stages of a film project that intervenes into Indonesia’s history of terror to re-stage its performance for the camera, to re-frame it in a way different from its repeated rehearsals in schools, on national television, on days of official memorial.

11 The aim is, in the first instance, to perform it in such a way that the operations of its obscenity can be grasped, so that the spectres it produces can enter the scene in a way that allows them to be addressed, acknowledged and contended. Whereas

G30S exists to justify a massacre it does not name and thereby conjures as spectral, this project seeks to stage a series of ‘perverse’ performances of official history that will name it and give it substance. It thus sets out to frame performances that contravene the generic imperatives of official history while nevertheless acting in its name and acting out its routines.

Here we focus on the performances of perpetrators. By giving perpetrators free reign to declaim their pasts for our camera, in invariably generic terms (in ‘testimonial’ interviews, re-enactments and even musicals), we have sought to deconstruct the ways in which generic and political imperatives always already shaped not only the victor’s history (including such scenes as we filmed), but also the violence of the genocide itself. By making these codes, conventions and scripts manifest, by marking the ways in which the historical accounts and enactments of the New Order are elements of a performative apparatus of terror, the project attempts to make these insights – as well as previously repressed historical detail – available to a political and historical imagination that can draw the process of national- and self-imagining from under the shadow and sway of catastrophe.

What follows is a critical reflection on an early moment of the project: the filmed encounter between two aging genocidaires at an execution site by a river in North Sumatra. From the many hundreds of hours of footage that followed the filmed encounter, this project is now resolving itself into three film works. Here we focus on just a few of those hours.

SNAKE RIVER: A ROUTINE ENCOUNTER

At the National Security Archive in Washington D.C. there is an anonymous and untitled folio of notes recording some of what little is publicly known of the 1965–66 Indonesian genocide. A Sumatran massacre of 10,500 people is recorded in a typical entry as follows:

CARD NO: 20 143

DATE: NO DATE

INDIVIDUAL: N. Sumatra

ITEM: From North Sumatra came a report of the slaying of 10,500 prisoners, who had been arrested for PKI activities. Their bodies were thrown into the Sungai Ular.

The Sungai Ular, or Snake River, is distinguished only by its size and relatively swift flow. It was for this reason that it was chosen as an execution site – unlike slower smaller rivers, the Snake River could be relied upon to carry the dead out to sea. Before the river meets the sea, it passes under the trans-Sumatran highway at Perbaungan, about thirty miles southeast of Medan, North Sumatra’s capital city. Within sight of a bridge where the highway spans the river is one of the clearings in the plantation belt where the Snake River was loaded with its nightly freight of bodies.

It is here, 38 years later, that we brought Amir Hasan Nasution and Inong Syah. Amir was commander of the Komando Aksi death squads for the Teluk Mengkudu district, where he killed, by his own account, 32 people at this clearing on Snake River. During the 1960s he was an art teacher and a primary school governor. After the killings, he was asked by the plantation management to found the management-and-military-dominated union that replaced the progressive union that he exterminated. He was later promoted to school inspector, and then regional head of the government’s Department of Education and Culture. After retiring, he was appointed head of his district’s KPU (Komisi Pemilihan Umum, or Public Election Commission). His duties were to ensure that general elections are ‘fair and clean’ – an ironic reward for a man who was earlier responsible for exterminating the largest political party in the same district.

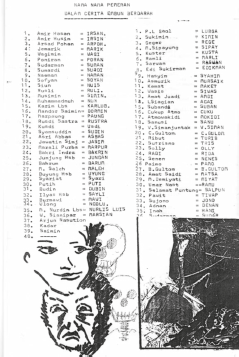

Fig. 1 On 22 January 1966, Amir Hasan’s first five victims were dumped in a disused well at Batang Kepayang, Teluk Mengkudu, North Sumatra. This illustration introduces a chapter in Embun Berdarah (1997) in which their ghosts narrate the massacres that follow.

Now the elections are passed and he has time on his hands. An avid writer and painter, he has already produced a lavishly illustrated book about his life; it is titled

Embun Berdarah (‘Dew of Blood’).

Inong Syah was a carpenter for the British rubber plantation, Harrison-Cross-field (now London-Sumatra). He was the youngest member in a death squad of nine. At the Sungai Ular, his role was to bring victims to the river and drag them to be killed.

Although they participated in the massacres during the same period, and were surely on occasion at the river on the same nights, Amir and Inong were in different death squads and did not meet until, decades later, they enthusiastically agreed to give an account for the camera of their role in the killings.

The two former death squad members stand on the roadside where a dirt path leads towards the river, down a steep bank, through the trees to a clearing by the water. They take this path, addressing the camera directly as they go. Each takes it in turns to play victim and executioner. Despite their age they go at it with gusto, assuming all the necessary positions for their demonstration: squatting with hands bound behind back; lying with legs raised while dragged by the ankles; pulling, pushing forcefully with feet in a wide stance to take the strain; bowed forward, nape of the neck exposed for decapitation.

From the unloading of bound and blindfolded prisoners to a demonstration of decapitation at the site of dispatch, they go through the motions of what was their nightly routine.

The fact that the performance does indeed make the process

seem routine has two somewhat contradictory effects. On the one hand, it allows us to understand the killings as

routine, as

mass killings, as systematic and thus scripted, rehearsed and generic. On the other hand, this scripted quality leads one to doubt the footage’s evidentiary value for any

particular killing. In this respect Amir and Inong’s performance is wholly typical of the perpetrators’ accounts this project has gathered.

12 Even the performances that seem most graphic appear not to be rendered as singular explications of specific events, but rather (as we shall explore in some detail below), as rehearsals of

genres whose register is the graphic.

A PROPER PERFORMANCE: THE TV PRESENTER’S LIVE SPECTACULAR

As Amir drags imaginary naked victims along the ground, beats them senseless en route to execution, perhaps the most unnerving thing is his relentless smile. It is a smile appropriate to the type of performance for which the camera seems to offer Amir an opportunity: that of the TV presenter.

Not only does Amir never stop grinning, he provides a seamless, present-tense narration of everything they are doing. As he shows the camera how they would drag victims on the final stage to the river, lines such as this are typical of his continuous commentary: ‘So now I am demonstrating how we drag him to the riverbank.’ The lines seem appropriate to an on-location reporter providing a blow-by-blow account of a shoot out between police and some bank robbers caught in the act (

Cops-style reality crime shows are a regular feature of Indonesian national TV programming), or perhaps even a sports caster providing play-by-play narration for a football match in which the national team is trouncing the traditional opponents.

Amir holds forth as if from a live event. His re-enactment of course is live, though as re-enactment it seems to gesture to the past. In as much as this past threatens to return, the re-enactment is a preview. Thus his presentation is strangely tensed, he seems neither to be referring to a particular past, nor to an actual present (we shall return to the future in a moment): not so much, ‘this is what we did’ nor ‘this is what we are doing’, as ‘this is what is done’.

In the observance of ‘what is done’ there is a peculiar formality to Amir’s presentation. Like anybody boasting on camera, Amir is camera-conscious, and in this decorous self-consciousness, his performance becomes more intensely, explicitly theatrical. And so, focused through the camera’s lens, two senses of performativity converge: there is the performative in J. L. Austin’s sense on the one hand (and just what, in the performative sense, this act

does we shall consider in a moment), and performative as in ‘theatrical’, on the other.

13Perhaps these two senses of performativity, despite Austin’s proscription of the theatrical, are already implicated in a ‘general iterability’.

14 As we shall see, this general iterability conditioned the staging of the massacres themselves, and therefore it conditions Amir and Inong’s performance both ‘then’ and ‘now’. This is not to claim that there were no originary acts that constituted the genocide. If only this were so. Rather it is to recognise that these fatal acts reveal the threat of repetition as a constitutive element of the performance of terror: not merely, ‘this is what is done’, but ‘this is what

will be done’.

It is this theatricality, conditioned by a general iterability, that makes visible the imprint of the generic – the performance of a script that appears to be well-rehearsed. Amir becomes a smiling presenter, and whenever he finishes a certain explanation, he pauses, refreshes his already gleaming smile, and gives the camera alternatively an enthusiastic thumbs-up or a ‘V’ for victory.

In his Playboy shades, pausing at the end of his demonstration to pose for a snapshot at the murder site, his is the same pose struck by those leering American soldiers in Abu Ghraib.

The perverse

tableaux vivants staged by Amir and Inong during their demonstration are re-enactments in an obvious sense, but just as those of Abu Ghraib, they are also rehearsals of ‘standard operating procedures’

15 (and certainly in the case of the latter, these procedures were codified in legal directives and described in detailed official interrogation manuals, all now in the public domain).

16 That is to say, the gestures of murder and torture are and were already re-enactments, just as these smiling snapshot clichés are pulled from a repertory of stock poses and therefore already and always repetitions. What Rebecca Schneider notes of the Abu Ghraib photographs also holds for the pose Amir assumes for his souvenir photo: there is a ‘citational logic’ in the staged triumphalism of these gestures – these are poses struck precisely to be repeated, not only through the rehearsal of the torture scene in other such institutions (in the case of Abu Ghraib) or the threatened return of anti-communist massacres (at Snake River), but also through the circulation of the images at viewings that are yet to come. Facing the camera, and looking deliberately toward a future spectator, the ostentatious theatricality amplifies the effect of the performance as show-of-force.

17

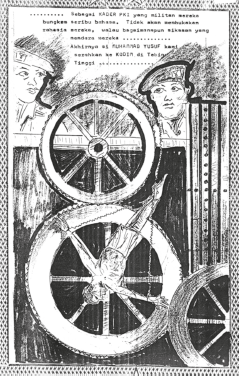

Fig. 2 Amir Hasan supervises the electrocution and torture of trade unionist Mohammed Yusuf in the machine room of the Matapao oil palm refinery; from Embun Berdarah

Here, in the future, looking back at Amir posing for his souvenir by the river where four decades previous he had struggled so tirelessly, we can ask how our camera is implicated in this staging. Indeed, in response to this image, we went on to explore the ways in which a filmmaking method that re-stages particular events and typical routines (‘standard operating procedures’) in a deliberately theatrical mode might insightfully frame the genocide’s operations as performances (that is, as oriented towards a spectatorship that was both contemporaneous and anticipated). These explorations lead to further questions: if re-enactment is scripted into terror’s performance and its staging as spectacle, what role might reenactment play in a critical and interventionist historiography; and how might such critical re-stagings and re-framings, in turn, render legible the scripts of such performances, describing their mises-en-scène, and revealing the ways in which the operations of the genocide were generic – that is, both routine and conditioned by genre?

Responses to these questions emerge from a more detailed consideration of Amir and Inong’s walk to the river.

GENOCIDE AND GENRE: HEROIC ROMANCE

At the start of his walk to the Snake River, Amir goes to great lengths to set the scene, wistfully referring to the ‘romance of their work’ (romantisme pekerjaan), describing the ‘fearsome night’ (malam takutkan) with the crescent moon hanging over the dark oil palm plantation. Amir even attempts to freeze the moon in its romantic crescent, as on an opera stage, suggesting that the moon was always a crescent, as if, during the time of the killings, the lunar phases froze to create the right suasana (ambience) for the bloodshed. In his remarkable memoir of the killings, Embun Berdarah, incredibly written in the first person from the perspective of the ghost of his victims, and illustrated with his own graphic paintings of the murders, Amir goes to even greater lengths to tell his story in an idiom faithful to a genre of romantic heroism.

Amir’s clichés include: ‘A great nation is one that knows her history’; ‘It was a matter of kill or be killed’; ‘A man who doesn’t know his history is a small man who accepts whatever comes his way’; ‘It was a time of revolution’; and the trauma and violence were all part of ‘the romance of life on this mortal earth’ (this last one, certainly, is self-invented).

Clichéd invocations of massacre as ‘heroic’ and ‘historic’ frame the killing as part of an epochal battle against an enemy of mythic proportion. This is a central trope in both Amir’s memoir and his and Inong’s performance at the Sungai Ular: set in a gothic landscape of ghosts, crescent moons and a watchful animal kingdom (frogs, monkeys and birds are invariably mentioned as the witnesses of Amir’s atrocities), the PKI is performed as a supernatural threat to be overcome. Amir empowers his victim as a mythic power to be conquered, allowing him and Inong to claim that power at the moment of slaughter, transforming themselves into heroes rather than people who committed the cowardly deed of executing those with no power to resist.

There is a tension between that which is

well-rehearsed about Amir and Inong’s performance and the fact that this is their first visit to the Snake River since the killings, and certainly their first time together. The scripted-ness of the encounter derives, surely, from the generic conventions conditioning all public discourse about the killings. For example, ‘the generation of ’66’ (

angkatan 66) has been celebrated as heroes, and so they easily slip into a well-rehearsed performance as heroic patriots who would stop at nothing to defend the nation.

18 Yet there is a grim misfit between their claim to be heroes and the events they perform. First, they must overcome the abject powerlessness of the victims, and this forces them into a supernatural register, conjuring magic powers of resistance. In

Embun Berdarah, Amir’s narrative strategy is to blame any obstacles faced by Komando Aksi on the mischievous ghosts of those already killed; thus, only posthumously do the PKI victims summon the resistance required to constitute their killers as heroes. Having established the epic struggle between killer and PKI members, the stage is now set for another genre, quite unlike that of patriotic heroic struggle: slasher or shock-horror.

GENOCIDE AND GENRE: SLASHER AND SADIS

Indeed, it comes as a real shock when, smiling as ever, Amir holds the stick he is using as a sword over his mouth and says, ‘Sometimes the executioner would drink the blood like this.’ Drinking blood is one of many grisly details unabashedly recounted. Others include how water, not blood, would flow from the amputated breasts of Gerwani members, how victims would urinate at the moment of death, how human corpses smell, how the

kebal (those imbued with the power of invincibility) were forced to eat and then defecate to overcome their magic powers, and how Komando Aksi rigged the bodies to float rather than sink so as to terrorise people living down stream.

19 These stories recount details that are routinely, to the point of cliché, called

sadis (an Indonesian appropriation of ‘sadist’); indeed, these stories are told in the register of

sadis. The enthusiastic recounting of the

sadis conjures, for the killer, an ultimate, metaphysical and magical power over death. It is a power to be relished, savoured, by rehearsing again and again the grisly details. Thus, through the genre of

sadis, may killers perform themselves not just as victors and appropriators of the PKI’s projected powers, but as men of preternatural strength with an

ilmu (or magical knowledge) far greater than that of their victims.

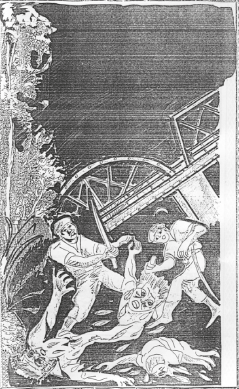

Fig. 3 An illustration of the killings at Snake River; from Embun Berdarah

Demonstrating in this way their own magical power over life and death is important, because it makes the killers (and sometimes when they attach names to their victims, the killings, too) specific, locating the power of death in the actual individuals who finally carried out the murders. (Here, as we shall see, is where Amir and Inong contravene the conventions of the official history, not least by identifying a locus of culpability, albeit one focused on instruments of murder, rather than its institution).

If the routine they performed seemed predicated merely on efficiency rather than theatricality, if they spoke only in statistical terms, performing themselves as no more than killing machines in the service of the army, it would be apparent that the true spectral power of death was located in those who assigned their ‘quotas’ (

jatah, the term used to describe their allotment of victims). When Amir and Inong highlight the singular and inevitably lurid moment of slaughter, by speaking the language of

sadis, Amir and Inong take for themselves, as individuals, the power of death otherwise vested in the institutions that commanded them.

Sadis, given its prominence on Indonesian TV networks like Trans TV, may be described as a non-fiction sub-genre of shock-horror. Violence is always explicit. Grisly and shocking details are told with pride and smiles, by respectable citizens – a school governor, in Amir’s case. Sadis is presented as public fact. But despite the fact that sadis is so self-consciously explicit, almost pornographically so, despite all the detail – or perhaps because of it – one cannot help but feel the loss of the actual event, its eclipse by its symbolic and generic performance. And because the grisly detail is rehearsed as a boasting, one cannot help but feel the performer’s interest, his investment in claiming power through the performance.

Perhaps it is this way in which the sadis always conjures something as held back that Inong alludes to when describing how dukuns (or shamans) always hold back the lion’s share of their knowledge from their students so that, if a dukun must fight his student, he will know the key to overcoming the student’s power, but not the other way round.

This provides an allegory for the gesture of withholding, a gesture that structures that most explicit of genres – the sadis, the shock-horror. For this withholding, this secret that one must always conjure as an excess or supplement even to the most luridly graphic story, also constitutes a certain ilmu, a mystique, a non-transferable power claimed by the performer who refuses to give away the whole game. As we have noted, the film G30S is analogously structured, and we are suggesting that structured into Amir, Inong and other killers’ performance of sadis is the same withholding, so that in a double movement, they can at once claim the godly power over life and death from their superiors, while at the same time locate this power beyond that which they reveal, in a mystique conjured as a supplemental spectre, encrypted as the obscene to their performance – a performance whose explicitness, as we shall see, is itself already the obscene to the official history.

Amir and Inong’s performance exemplifies this replenishment of spectral power through storytelling, through performances that seem well-rehearsed, even scripted. Inong in particular tells a lot of graphic stories. In his own community, Inong’s stories, whether true or merely ‘empty talk’ (

omong kosong), disseminated far and wide via Inong’s ‘big mouth’ (

mulutnya sampai ke mana mana), have acquired for him the reputation of being an

algojo, or executioner, a word often used generically – and

sotto voce – for anybody rumoured to have participated in the killing. This reputation makes Inong feared, anticipated as one with sufficient ties to the terrifying Indonesian state to be instructed to kill, and then be protected. There is a tense relationship to an unstable logic of anticipation, as Inong acquires a force precisely because his spectral violence threatens to suddenly explode into the spectacular. As such, this constitutes a real social power for Inong in his community – one constituted through stories, through his big mouth.

UNDER THE SPELL OF STORIES

These stories are performatives (in Austin’s sense). It is not enough to drink blood or cut off heads; one must also tell about it, rehearse it again in whispered performances and repeated gestures, if one wants to conjure the spectral power claimed during the massacre, and manifest it as a social force. The performances of killers as they rehearse these stories are what accomplish this conjuration.

In her essay on gender constitution, Judith Butler argues that the constitutive performatives of gender are ‘objects of belief’.

20 However, the ‘conjurative’ performances of those such as Amir and Inong need not be correspondingly charged with credulity. That is, they need neither themselves believe all they say, nor need their audience, for the conjuration to be effective, any more than they need believe in the propaganda about a murderous PKI to act

as if they believed it.

Acting ‘as if’ the PKI posed an overwhelming threat was a moment in the appropriation of that threat’s projected power, moreover one needs to be recognised as a killer in rumour and whispered gossip. For this reason, establishing yourself as a killer – or potential killer – in the eyes of the community may be more important than participating in the killing itself. The killers, or would be killers, act out of the fascination of their own terrorising fiction. Thus may people brag of things they never did or exaggerate their role. This attests to the power of narrative – of rumour, stories and performance.

Taussig writes about how such terror can lead those under its spell to themselves do terrible things. Writing about the Amazonian rubber boom, Taussig describes the reaction of colonists to the spectral terror of the imaginary Indian threat:

The managers lived obsessed with death, Romulo Paredes tells us. They saw danger everywhere. They thought solely of the fact that they lived surrounded by vipers, tigers, and cannibals. It was these ideas of death, he wrote, that constantly struck their imagination, making them terrified and capable of any action. Like children, they had nightmares of witches, evil spirits, death, treason, and blood. The only way they could live in such a terrifying world, he observed, was

to inspire terror themselves.

21

The nature of this ‘terrifying world’ needs real thought. Does it mean that the colonists actually believed they were surrounded by cannibals? Taussig does not quite say so. In the case of 1965, would it mean that Amir and Inong actually believed the PKI kept secret death lists with their names on them, and were poised to massacre anybody who believed in God – despite the fact that PKI members prayed in the mosque as much as everybody else? If they did believe it, what is the nature of such belief? Or, perhaps the colonists described by Taussig were obsessed by cannibals without having actually to believe that they were surrounded by them. Perhaps they lived ‘in such a terrifying world’ because they were told, and were telling each other, terrifying stories about their world. But that does not mean they actually believed the stories. What matters is the genre of story, how it is repeated, how it is insinuated as rumour into the subtext of daily life, its context of circulation. A ghost story can terrify without one believing that it is true. Narrative has the power to conjure terror, and somehow, as with ghost stories, this power is attractive; we want to hear stories, even, or perhaps especially, terrifying ones; we voluntarily place ourselves under the spell of the terrifying effects of stories.

This is not a unique observation about our susceptibility to narrative; we merely suggest that this dynamic of narrative can have very real and terrible political consequences. Just as we need not discuss belief to account for the spectral effects of ghost stories, we need not when we describe the effects of anti-PKI propaganda, or stories about Indian savagery. In order to kill, and to kill so many, Inong and Amir may indeed have been under the spell of this narrative terror. But when we say Amir and Inong were under the spell of terror, we do not say anything about what they believed. Rather, we mean that they were attracted by the spectral power of terror invested in the phantasmatic PKI by all the stories about them then in circulation, and they availed themselves of the opportunity to appropriate some of this power by participating in the killing. It does not follow that in order to be under the spell of terror they had to believe the stories that conjured it in the first place. This is a terrifying and terrible actuality: that one could commit genocide under the spell of stories – stories of heroism, horrors, ghosts.

These stories haunt, yet are themselves haunted. What haunts these stories of

sadis is the real. These displays of excessive visibility, by eclipsing with their generic gore the terrible singularity of each murder, make visible the relationship between obscenity (in the everyday sense) and its own obscene – the historical real itself. And in this evocation of the historical real, what is made real is the

absence of the victims – that is, their death.

SHORT CIRCUITS: CAMERA AS LURE, FILM AS INTERVENTION

If the haunting persistence of the massacres remains the source of Amir and Inong’s conjured power, we will be able to see now how it is also their undoing. For they have done more here than merely provide us with an opportunity to analyse the narrative and generic imperatives of their recount.

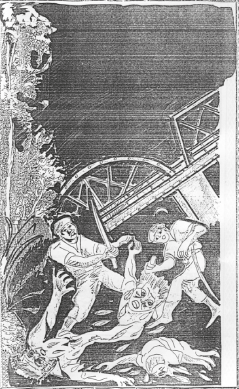

We have suggested that Amir perceives the filming as a rather unusual public relations opportunity – to claim, rather than deny, the killings and so too to claim the spectral power that attends them. Yet Amir’s bid for publicity is fraught with contradictions. As he writes in his memoir, Embun Berdarah, and repeats for our camera when he first presents the book to Inong, ‘This is for people who wish to know more about our struggle, so that what we did will never be forgotten.’ He makes photocopies of the book, but then tells us the book is full of national secrets and should not be made public. He changes all the names in the book, but then on the final page provides a key so the reader can know the names of the actual people upon whom the characters are based.

Following the walk to the river, he suggests a collaboration to adapt his book into a musical film, and enthuses about the project to his friends. When his friends try to warn him off the project, suggesting the film might be too explicit (and thereby violate the national taboo around publicly discussing the massacres), he changes all the names in the screenplay and sets it on another planet, leaving the story intact. He is, after all, reluctant to give up the enterprise. Whole segments of his own community are already in the grip of his power – that is, they are afraid of him – and he hopes that the film he would make might enlarge the compass of that power, drawing others into his fold, manifesting publicly that which has hitherto been made explicit only on the unread and moldy pages of his own memoir, written yet secret.

If he does see the film as somehow condensing his claim to spectral power, in what fora of presentation or circuits of distribution does he see his power emerging? That is, who is Amir’s imagined audience? Given how worried he is about ‘revealing secrets’, despite his vigorous boasting, it is probable that he has no

particular audience in mind. For as soon as Amir imagines any

particular audience, he becomes aware of

risk. It is only when he imagines actual and singular human beings viewing his filmed performances does he realise that he is providing substantive and singular information. That is, only when he imagines a specific audience does he realise that his performance substantiates so much that had previously been unsaid, condensing the audience’s reception of his image into the transaction of a secret. Here is where he imagines danger, and suggests changing names.

At other times, for instance with Inong at the Snake River, rather than imagining any particular audience, it is as if he is performing for an anonymous and, like spectrality itself, miasmic public defined and interpellated by an equally generic ‘media’. Or perhaps he does not even imagine the public, but only the system of images that constitute ‘media’. Perhaps it is the rather impressive technology of filmmaking itself that enables Amir to avoid thinking about how his performative project, in his mind, lacks an audience. That is, perhaps the spectacle of filmmaking functions like a fetish, a substantive metonym for the missing audience, as well as a concrete metaphor for the abstract apparatus of television and media as system of images. Thus does the camera entice Amir to forget, momentarily, the absurdity of the fact that he has authored and starred in performances for nobody.

Fig. 4 Original and Fictional Names from the memoir, Embun Berdarah. The right column is victims, the left perpetrators and their supporters.

The film Amir has set out to make is self-consciously influenced by Pengkhianatan G30S PKI. (In an unrecorded discussion about how to transform his novel into a heroic musical, he said that the model for him would be G30S.) By conjuring a PKI opponent roughly consistent with that conjured in G30S, he would claim some of the latter film’s force: as we have seen, G30S has also been an instrument of terror, the film itself is part of the ilmu used to conduct the séance of Indonesian state terror, attempting to conjure the spectral power of the PKI, condense it in the film, and claim it for the state.

He hoped to use the film to close the circuit of spectral power’s passage from them PKI to himself, and to amplify the strength of this power with the dissemination of his image through his generically imagined audience. But rather than complete it, the film

shorts this circuit of acquiring spectral power. That is, once Amir and Inong make a spectacle of their spectrality, they undermine their own power, because their power was established precisely as that spectrality conjured by that which was

obscene, unspoken and unsubstantiated (and ideally, for the architects of genocide, unsubstantiatable).

By publicly performing the well-rehearsed but obscene scripts that constitute the massacres’ systematicity, Amir and Inong reveal that they were instruments of a system rather than its masters – they show themselves to be culpable functionaries. And so, in their attempt to use film to complete the circuit of acquiring spectral power, and to manifest spectral power as actual power, they reveal that the power was never theirs in the first place. Amir was ordered to kill by his brother-in-law, an army major. The killers were under army orders. They were killing only those whom they were authorised to kill. Lured by the opportunity they perceive, Amir and Inong get sloppy and fail to meet the terms of their own genre. They name names, including their own and, worse still, their superiors. They stumble and make precisely the kind of public admissions that have been proscribed.

Particularly, by naming names and describing the killing machine in such detail, the footage confirms what had long been suspected, or substantiates that which had been spectral. Tellingly, after our first visit, Amir would never perform another ‘re-enactment’ (peragakan) as such. However, the route to the historical scene through fiction, no matter how transparently direct, remained open.

Originally, Amir had asked to produce an explicit adaptation – albeit a musical, heroic one – of his memoir. After talking (bragging?) about this with friends in the regional government as well as veterans of his Komando Aksi group, including a member of the Badan Inteligen Negara (National Intelligence Body, Indonesian equivalent to the CIA), he was told that this might not be such a good idea. He was warned against doing any more filming about 1965–66.

22 He was crestfallen, until he came up with his strategy of interplanetary displacement.

23He considers this within the sacrosanct realm of ‘art’, and thus somehow no longer about his experiences, but continues to make the same blunder of making explicit that which had been obscene. The disguise of changed names and the relocation of events to an imaginary cosmos already structured by the well-rehearsed genres of patriotic heroism that code films like Star Wars, a model for Amir’s adaptation, is fragile. Not only do we know all the names already, Amir is repeatedly arrested and possessed by the singularity of his own experience and repeatedly interjects tellingly specific detail. He even wants to shoot his film in more or less the historical locations, with original costumes and weaponry, along the muddy rivers of Sumatra’s oil palm belt, despite its purported interplanetary setting.

Amir’s use of historical performance as a performative bid for power, and his veiling of that performance, even from himself, in the name of ‘art’, is repeatedly troubled by the tension between the spectral and the substantial. The meaning, force and consequence of circulating substantiated stories with named killers and victims is vastly different from that circulating unsubstantiated and spectral rumours. Moreover he does so on record. Not only do they substantiate their stories before the eye of the camera, their self-conscious histrionics make all-too-evident the generic imperatives that have constituted so many thousands of similar historical performances that remained unrecorded, always and again

live. As a living threat, these performances are moments in the spectral circulation of terror; as

material artifacts, they can be analysed critically, decoded, rendered evidential – that is, their own theatricality, borne of their eager attempt to seize the filmmaking as

opportunity, produces a kind of over-acting that makes obvious the fact that their performance is scripted. These previously inadmissible scripts, thus revealed through the obviously generic qualities of their histrionic performance, lose the obscenity from which they derived their power.

It is through cinema that Amir and Inong’s power dissolves at the moment that their performance is condensed onto tape and taken away from them, beyond their control. They have revealed at once the details of their own role and the generic imperatives of a broader chain of command. Above all, they transformed rumour into evidentiary account. Rendering the spectral explicit allows it to be critically reframed, and this process opens on to the potentially redemptive and retributive possibilities of this project. Once captured on film, these performances can be given over to those very subjects that the performance of the massacres was and is intended to physically and symbolically annihilate – survivors of the terror and those still under its sway.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERFORMANCE

This moment of restaging the perpetrator’s performance

in ways that allow survivors to imaginatively respond to a history bent on their destruction is beyond the scope of such a brief essay, one which has focused on just four hours of footage from an archive of many hundreds of hours, and one which has focused on only the first moment of a production and research method that can be thought of as an

archaeological performance.

24This method of archaeological performance entails successively working with and through the gestures, routines and rituals that were the motor of the massacres, as well as the genres and grammars of its historical recount, typically moving from interview and re-enactment with the historical actors, such as that of Amir and Inong on the Snake River, to increasingly elaborate re-stagings of the events related in the interviews. Between a buried historical event and its restaging with historical actors this method opens a process of simultaneous

historical excavation (working down through strata), and

histrionic reconstruction (adding layers of stylised performance and recounting).

So, to close, let us briefly look at one of those moments of histrionic reconstruction with Amir Hasan.

ON CECIL B. DEMILLE AT LAKE TOBA

In his study of the psychology of denial in perpetrators of atrocity, Stanley Cohen argues that ‘Participants glibly appeal to “history” for vindication. A Serb soldier in 1999 talks about the Battle of Kosovo as if it happened the week before.’

25 The power of the victims in the past, be it actual or mythic, is used to figure the victims not as victims but as powerful adversaries to be overcome in heroic defence of the nation. Amir and other perpetrators’ repeated appeals to the propagandistic commonplaces of PKI treachery at the 1948 Madiun rebellion and 1965 ‘Gestapu’ coup – even if both are ultimately spectral conjurations in their own right – perform this same role.

26 So does Amir’s clichéd claim that ‘they would have killed us if we didn’t kill them first’.

But Cohen continues, referencing Michael Ignatieff’s 1997 study of ethnic cleansing in the Balkans:

This nationalism, Ignatieff points out, is supremely sentimental:

kitsch is the natural aesthetic of an ethnic cleanser. This is like a Verdi opera – killers on both sides pause between firing to recite nostalgic and epic texts. Their violence has been authorized by the state (or something like a state); they have the comforts of belonging and being possessed by a love far greater than reason: ‘Such a love assists the belief that it is fate, however tragic, which obliges you to kill.’ This is your destiny.

27

In the case of Amir Hasan, Cohen’s description of the Verdi opera proves to be more than just a metaphor. In a still-in-progress part of the film practice Amir has been working with us to film a musical adaptation of his memoir, Embun Berdarah. Amir himself has assumed the role of ‘film director’ for this musical film-within-our-film. To this end, he has recruited a university choir to create the music. He then wrote a series of poems and speeches, and recited them ‘amidst the beautiful nature of Indonesia’ in North Sumatra’s crater lake, Danau Toba, a well established tourist destination. Basing these speeches on Cecil B. De Mille’s introduction to The Ten Commandments (1956), which we had showed him as one of many possible models for his production, passages include:

Why make this film? Because this is my creation, the fruits of my own imagination, expressing the history of my own life.

Let me tell you something you should know: [Quoting directly from Embun Berdarah] The red sunlight shines down upon the earth. Red, green, blue and other colours struggle to dominate the heavens. Banners emblazoned with writing seek to discredit everybody else. But storm clouds are gathering, and they cannot hold back the rain of blood that will fall upon our mother, the Earth. This is the fight between good and evil.

This is the romance of life [romantika kehidupan] in our mortal world.

Amir directly addresses the audience from this picaresque scene, pausing to wave and shout, ‘ahoy!’, to a lake-tour boat that passes behind him. Paraphrasing De Mille, he declares, ‘By watching this film, you will have made a pilgrimage to the actual land sanctified by blood in the patriotic battle to save our nation.’ Under a soundtrack of choral music, Amir Hasan delivers his speech before a shifting background of clumsy tourists learning traditional Indonesian dances, sipping multi-coloured cocktails, and bemusedly enjoying Amir’s poetry amid the tropical paradise.

NOTES

An earlier version appeared in Critical Quarterly, 51, 1, 2009, 84–110. This version has been revised and updated.