The Death of the Meme

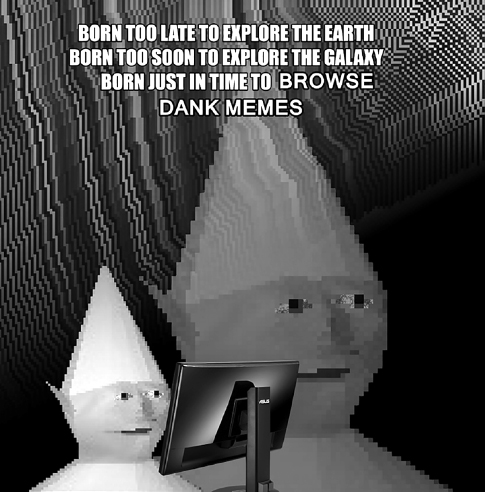

Figure 2.1 A self-referential image macro, ironically pairing the qualifier dank—slang for high-quality marijuana—with browsing memes. It reappropriates a character called Gnome Child from the 2001 online game Runescape. Collected in 2014.

On May 15, 2014, Fernando Alfonso III published a piece for The Daily Dot speculating on the bleak future of internet memes. Referring mostly to image macros (such as “Hipster Kitty” from chapter 1), Alfonso (2014) argues that “they’ve been bled dry of all their novelty, and they’re just not funny or relevant anymore.” Describing the “dilution” of these once novel texts, he speaks to their rise and resulting “overkill” on Reddit, which he says took steps to broaden its content beyond the visual quips. He speaks to the seep of image memes into “mainstream” sites like Facebook, which had in response adjusted its algorithms to favor articles over images. The mounting evidence suggested a bleak future indeed. For whatever reason, memes—at least as a label for a specific set of niche texts—just weren’t cool anymore. Like punk rock and craft beer, memes were dead, crushed under the weight of their own success. In light of these charges, a study of the formal and social structures underscoring memetic media has to reckon with the alleged demise of their cultural resonance.

Like Alfonso’s, my moment of reckoning also came in 2014, when I was discussing my Ph.D. dissertation with a student. “I remember memes,” the college sophomore said. “They were really big in high school. Junior year.” The thought that my two-year-old dissertation was now a historical analysis of a dead communicative genre prompted some angst. And I wasn’t alone. Whitney Phillips, expanding her 2012 dissertation into a 2015 book on self-identifying internet trolls, discusses similar shifts and similar angst. Trolling—as the term was employed by Phillips’s research informants—emerged from the same media ecology as many esoteric internet memes. They had grown up in the same “cultural soup” on sites like 4chan, Something Awful, and others during the early 2000s. Phillips chronicles the increasingly self-referential, intertextual, and esoteric memetic practices of trolls during these years, but also the dilution of these practices toward the end of her study. “By early 2012,” Phillips writes, “it became painfully clear that I was no longer writing a study of emergent subcultural phenomena. I was instead chronicling a subcultural lifecycle” (2015b, 44–45).

By 2012, Phillips (2015b) reports, both the terms troll and meme were exhibiting simultaneous mass usage and definitional ambiguity. Phillips argues that the rise of the reference database Know Your Meme signaled a major shift in the subcultural dimensions of internet memes, as well as trolling. The database grew from a small 2007 video project affiliated with the site Rocketboom into a popular wiki purchased by the larger Cheezburger Network in 2011. “Know Your Meme was written with the novice in mind,” Phillips says, “with detailed, almost clinical explanations of the Internet’s most popular participatory content. KYM thus helped democratize a space that had previously been restricted to the initiated” (139). By 2012, Know Your Meme had established itself as the go-to reference guide for internet memes. This was also the year of the last ROFLCon internet culture conference, which founders Tim Hwang and Christina Xu (2014) say became dauntingly commercial. Likewise, in 2012, 4chan’s founder Christopher “moot” Poole told Forbes that “as online culture has moved offline, pop culture has moved online, they’ve met in the middle, and become the same thing now” (quoted in Olson 2012). In this intertwine, the subcultural resonance of internet memes had seemingly run its course.

By 2015, it seems we’re well past the reign of the pantheon of esoteric stock characters that emerged from sites like 4chan, Reddit, and Tumblr over the last decade. Now the invocation of the very term meme on those same sites is more and more ironic. Figure 2.1 is an image macro mocking internet memes and the cultural practices surrounding them. The language in the image reappropriates a memetic sentiment sometimes quoted on participatory media sites. One iteration, posted to Reddit’s /r/Atheism subreddit in 2012, posits that “we were born too soon to explore the cosmos, and too late to explore the earth. Our frontier is the human mind. Religion is the ocean we must cross.”1 In figure 2.1, the reference to “dank memes” as the site of exploration in the present compares negatively to the great cultural feats of the past and future. “Dank”—a term of praise for quality marijuana—can be read ironically here, because of its associations with “stoner” slang and its juxtaposition with the high ideals of scientific exploration.2 Further, the font in the image shifts just as “browsing memes” becomes the subject, indicating a shift in tone, a juxtaposition constituting a punch line. The image—composited from a character in the online game Runescape called Gnome Child—resonates in the blank stare of its subject and the dreamlike, glitch art space behind him, which creates a larger, more opaque version of him—almost a psychic projection; the blackness behind the figure birthing asymmetrical neon green, blue, and red lines. All this signals mockery, and uses stoner slang and a preteen-oriented videogame to hone that mockery. Whatever “browsing dank memes” is, exploring the galaxy it is not.

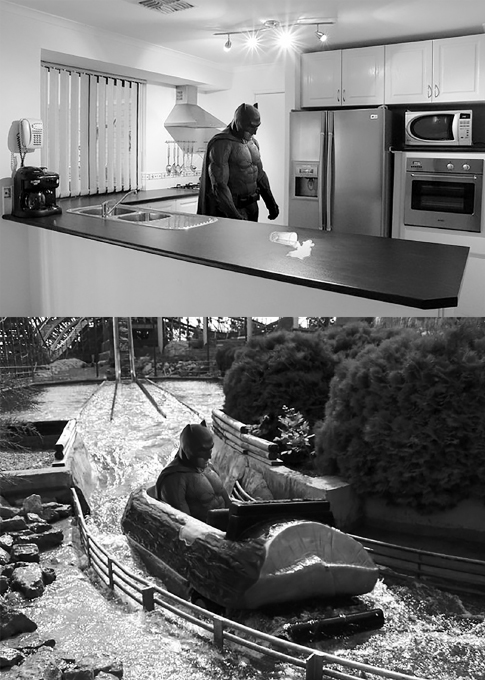

Figure 2.2 also denigrates memes by connecting them to juvenile contexts. This image was posted to /r/TheWalkingDead, a subreddit devoted to the popular Walking Dead comic, television, and videogame universe. Part of a playful “photo recap” for season 5, episode 13 of the show, the post shows Carl and his father, Rick—survivors of a zombie apocalypse—at a party in a walled community they have recently entered. Carl is shown socializing with the other teenagers in the town, while Rick socializes with the adults. In the photo caption, Carl tries to bond with his fellow teens by asking them if they remember memes. Rick is not impressed. In the thread accompanying the post, a Reddit participant “didn’t get” the meme joke, and asked for an explanation. The answer was that Carl is “a teenager, talking to other teenagers. Who haven’t seen the internet in God knows how long. Carl wants to remember memes.” The two responses to that answer—coming around the same time—were “dank may mays, if you will” and “dank memes m8.” Both responses invoke the faux praise “dank,” and both denigrate memes beyond that. The first calls memes “may mays,” a common pejorative term (an ironic mispronunciation of the word meme), while the second includes the slang “m8” (shorthand for mate, or friend), another example of slang vernacular invoked ironically. All this, combined with the fact that Carl is not generally a well-regarded character on the subreddit (due to his very teenage awkwardness), contributes to a running joke about texts gone stale.

Figure 2.2 Two images from a 2015 episode of The Walking Dead, captioned by a Reddit participant for an /r/TheWalkingDead “photo recap” thread. It annotates a scene featuring Carl and his father, Rick. Posted on March 10, 2015.

But the narrative of subcultural corruption is often far too simplistic. The idea of a discrete, bounded subculture that opposes a hegemonic mainstream is fallacious, or at least murkier than an easy binary. Holly Kruse (2003) and Wendy Fonarow (2006) argue that the relationship between “indie” music scenes and “mainstream” music cultures is much more interdependent than the “subcultural authenticity” narrative suggests. The same could be said for the niche practices that have loosely labeled “internet culture” over the last decade. Lamenting that “4chan is too safe now,” or that “Reddit is too popular,” or that “Tumblr is too commercial” obscures the ways in which those sites, their participants, and the texts they create have always been intertwined with mainstream culture. Even the earliest 4chan memes reappropriated establishment media like pop songs, television characters, and videogames. The line between internet culture and popular culture has long been a blurry one.

Memetic media didn’t start with 4chan, just as they didn’t end with the final ROFLCon. Memetic practices persist, even if the specific resonant texts shift over time. If we’re tired of stock character macros in 2015, it doesn’t mean that “memes are dead”; it indicates that those memes don’t hold the specific cultural capital they did in 2010, or even that they hold cultural capital for people other than us. The relationship between niche collectives and broader cultural practices is always porous. The relationship between subcultural internet memes and broader memetic participation is porous as well.

Memetic logics are alive and well, more vibrant than ever, even if the corpus of texts in 2015 is wider and more widely distributed than the collection of characters and tropes that emerged out of esoteric forums a decade ago. The same memetic logics help craft both “stale” stock character macros and the collective vocal scorn for those stale texts. Despite their denigration of memes as subcultural texts, figures 2.1 and 2.2 still depend on these memetic logics. They’re obviously both multimodal, reproducing an aesthetic used over and over in memetic media. They’re both premised on reappropriation: figure 2.1 in its single panel combines an aphorism, a videogame character, and slang for marijuana, while figure 2.2 collects two photos from a set of about 150 captioned images, all taken from one episode of one TV show. Both were produced for collectivist participatory media sites. Both figure 2.1 and the conversation about figure 2.2 demonstrate the resonance of the mocking phrase dank meme, which spread in late 2014 across multiple participatory media sites. The insult is every bit as memetic as the targets it’s applied to. “Memes are dead” is thus a well-worn meme itself, one driven by memetic logics. These logics still underscore the creation, circulation, and transformation of collective ideas, and the memetic lens is apt in understanding a vast array of populist practices, both esoteric and widespread.

To be sure, there is a lot to learn from the “good old days” of memetic participation on sites like 4chan and Reddit, and the rest of this book will draw from this lineage. Even in 2015, more insular or bounded online collectives still have their fair share of inside jokes and esoteric references, and there is value in understanding how memetic logics and texts are used to facilitate both the ingroup affiliations and the outgroup antagonisms we’ll see in chapters 3 and 4. Even in a cultural studies moment “after subculture” (see Bennett and Kahn-Harris 2004), the concept of a “social imaginary” is significant. Arjun Appadurai (1996) argues that mass media help to create these imaginaries, collectives that feel a sense of communal identification even if they don’t demonstrate the interdependence of a traditional community. Although subculture has a different meaning today than it had when Dick Hebdige (1979) penned his study of British punks in the 1970s, it can still describe how members of a collective discursively cast themselves as antithetical to, apart from, or in opposition to a nebulous discursive “mainstream.” This analysis would be incomplete if it assessed memetic media without exploring the niche collectives that have become tied to the term. There is utility in understanding both the esoteric imaginaries and the mass participants producing memetic media.

In evidence of that utility, the rest of this chapter—pairing with next chapter’s discussion of vernacular—will build a case for the persistent power of memetic logics by examining their communicative characteristics, their social dynamics, and, ultimately, their role as a lingua franca in diverse mediated conversations. The sections to follow will assess the grammar surrounding the memetic logics introduced in chapter 1 and will tie memes to a lineage of reappropriation by bricolage and multimodal poaching. Even if memetic participation has gone “mainstream,” even if it’s more dispersed now than it was in 2005 or 2008 or 2011, even if Alfonso (2014) and The Daily Dot cite legitimate shifts, memes still matter. Whether or not the subculture has lost its edge, memetic logics are as pervasive as ever.