4. The Wild West:

The Colonisation of Europe

On the Way to Europe: Modern Humans in the Levant and Turkey

Considering that Europe is geographically so close to Africa, it seems remarkable that modern humans made it all the way to Australia some 20,000 years before we find any evidence of their presence in Europe. Why did it take so long? The answer is likely to be complex, involving geographical and environmental barriers, and, perhaps, the presence of other humans already occupying Europe. Because, whereas in most of Asia (with the notable exception of Flores) earlier humans had vanished long before moderns arrived on the scene, Europe was the domain of the Neanderthals.

There is a huge gap between the appearance of the first anatomically modern humans in the Near East – in the Skhul and Qafzeh caves in Israel, some 90,000–120,000 years ago – and the first evidence of modern humans in Europe – at around 45,000 years ago. After Skhul and Qafzeh, modern humans disappear from the Levant for around 50,000 years, although it seems that, during this time, modern humans were making their way eastwards along the coast of the Indian Ocean.

From Arabia and the Indian subcontinent, it may seem that the colonisers should have been able to spread north into Europe with ease. Stephen Oppenheimer1 suggests that, just as deserts may have blocked the northern route out of Africa for much of the last 100,000 years, the way from the Indian subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula to the Levant was also sealed off by geographical barriers: by the Zagros Mountains, and the Syrian and Arabian deserts. While the beachcombers surged eastwards, their northwards expansion into Europe was blocked. But around 50,000 years ago, the climate warmed up briefly, for a few thousand years. Oppenheimer argues that this warming opened up a green corridor from the Arabian Gulf to Syria, a gate into Europe.

The colonisers could then have spread north-east, skirting the Zagros Mountains, up the coast of what is now Pakistan and Iran, and up the River Euphrates into modern-day Iraq and Syria, making their way from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean coast. Some archaeologists argue that Upper Palaeolithic sites along the Zagros Mountains support this route, and indeed suggest that Upper Palaeolithic technology may have originated around the Zagros Mountains, with some dates in excess of 40,000 years.2 However, these dates need to be treated with caution: firstly, these are dates at the very extreme of what is considered reliable for radiocarbon dating, and, secondly, the dates were reported in the 1960s, long before the new sampling and calibration techniques were applied. However, the types of tools found at the Zagros sites are similar to the earliest Upper Palaeolithic tools found around the eastern Mediterranean, known as the ‘Levantine Aurignacian’.

Routes into Europe. The black footprints represent the first modern humans to reach Europe, bringing with them the Aurignacian culture, starting around 45,000 years ago; the grey footprints represent the later incursion of the Gravettian people, beginning around 30,000 years ago.

The route from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, following an earlier southern dispersal from Africa, seems a reasonable suggestion, but other researchers still favour a simple northern route out of Africa, from Egypt. But whichever of these routes was taken, we would expect to find part of the archaeological trail in the Levant and in Turkey; in other words, in those countries that border the eastern Mediterranean.

There is a growing body of archaeological evidence for the earliest modern humans in the Levant and Turkey, in the form of Upper Palaeolithic stone tools, and ornaments – and some bones.

In the 1940s, archaeologists began to excavate down through 19m of deposits at the site of Ksar ‘Akil, near Beirut in Lebanon. They found twenty-five layers containing Upper Palaeolithic archaeology. In the deepest layers, they found Levallois-type technology (stone tools made from prepared cores), typical of the Middle Palaeolithic, alongside classic, reshaped Upper Palaeolithic tools, like end-scrapers and burins. In later layers, the Levallois cores are replaced by cone-shaped prismatic cores, from blade manufacture – a hallmark of the Upper Palaeolithic. Dating of layers above and below the earliest Upper Palaeolithic stratum at Ksar ‘Akil suggests that those tools were being made there somewhere between 43,000 and 50,000 years ago.3 And the discovery of a skeleton at Ksar ‘Akil confirmed that it was modern humans who were making those tools.4 Dating of the Upper Palaeolithic at Kebara also suggests the presence of modern humans in the area by 43,000 years ago.5

Tracing the northwards expansion of people into Turkey has been problematic. The Palaeolithic of Turkey has long been in the shadows, mostly because comparatively little archaeological research has been carried out there.6 Many Palaeolithic sites in Turkey are just ‘findspots’, where stone tools have been spotted on the surface. Relatively few have been excavated, but in the last twenty years archaeologist have been striving to plug this gap, and some interesting finds have emerged, which help us to trace the journey of those early European colonisers.

The archaeological site of Üçagizli lies on the rocky south-west coast of Turkey, about 150km north of Ksar ‘Akil, and near the city of Antakh (ancient Antioch). The partially collapsed cave was first discovered in the 1980s, and excavations began there in earnest in the 1990s, leading to the discovery of Upper Palaeolithic artefacts in red clay sediments. The tool manufacture at Üçagizli seems to follow a very similar pattern to Ksar ‘Akil: the oldest Upper Palaeolithic layers in fact contain a mixture of ‘Middle Palaeolithic’ technology alongside more classic, retouched tools. Just as at Ksar ‘Akil, the Levallois cores disappear in the higher layers, to be replaced by prismatic cores, where blades have been knocked off by soft-hammer or indirect percussion. But at Üçagizli there are also tools made of bone and antler. The earliest Upper Palaeolithic layers date to between 41,000 and 44,000 years.3

Throughout the Upper Palaeolithic layers at both Ksar ‘Akil and Üçagizli, the archaeologists discovered classic signs of the Upper Palaeolithic – and of modern humans: ornaments. The vast majority are small seashells, pierced through to be used as beads or pendants. More than five hundred shell beads have been found at Üçagizli alone. It’s possible to see how the holes have been created in the shells – some by scratching away, while others seem to have been punched through with a pointed tool – and it’s quite clear that these holes were made by humans and not by other, natural processes. There were shells from marine snails Nassarius gibbosula, Columbella rustica and Theodoxus jordani, as well as the pretty, ridged bivalve Glycymeris. From the large collection of shells at Üçagizli, it looks as if those hunter-gatherers also enjoyed the taste of seafood: bigger shells, from limpets (Patella) and the edible snail Monodonta also appear, unpierced, in the archaeological strata. The archaeologists were sure that these shells had been collected for food as they were not wave-worn like the empty seashells that wash up on beaches, and, in addition, many of them were burnt.

The shell beads from Üçagizli are not – by a long stretch – the earliest ornaments: the pierced shells from Skhul in Israel date to between 100,000 and 135,000 years ago.7 Shell beads were also found in Blombos Cave, dating to around 75,000 years ago, and the evidence for ochre use goes back to beyond 160,000 years ago at Pinnacle Point. These finds suggest that art and ornamentation is probably almost as old as the human species itself. But the Üçagizli beads are useful as a marker for modern human presence. They show that modern humans were bringing with them a shared culture, and perhaps an awareness of identity and a system of communication that did not seem to have been there among archaic human populations.3

There is a scarcity of Upper Palaeolithic sites in Turkey. Kuhn6 argues that the Anatolian Plateau, most of which lies more than a kilometre above sea level, would have been a cold, unwelcoming place during the late Pleistocene, and that modern humans (as well as other animals) would have gravitated towards the warmer coast. With a higher sea level today, any Pleistocene coastal sites would now be submerged. Nevertheless, Üçagizli is an extremely important site, a stepping stone into Europe, with Upper Palaeolithic artefacts going back more than 40,000 years, anticipating the spread of the classic Upper Palaeolithic culture, the ‘Aurignacian’, from east to west across Europe, between about 40,000 and 35,000 years ago.8

This all seems to fit together very neatly, but we need to be aware that these initial movements into Europe are occurring at an awkward time for radiocarbon dating, and some dates obtained during the twentieth century might need reassessment. And not only do archaeologists and anthropologists argue about the exits from Africa, there is also debate about the route into Europe, and where Upper Palaeolithic culture began. Kuhn6 seems convinced by the dating of Üçagizli, but also suggests that this culture may represent a spread southwards from Europe, rather than northwards from the Zagros Mountains and the Levant. Other researchers have argued that Upper Palaeolithic culture may have arisen in the Russian Altai, north of the Zagros Mountains, with a dispersal of modern humans, carrying this technology, coming into Europe from around the Caucasus Mountains and the northern coast of the Black Sea.9

However, most researchers seem to agree that Üçagizli and Ksar ‘Akil fit very well with a model where modern humans, bearing an Upper Palaeolithic, pre-Aurignacian toolkit, arrive in the Levant, spread north into Turkey, and then westwards through Europe.8

Crossing the Water into Europe: the Bosphorus, Turkey

Making my own way up through the Asian part of Turkey, I reached a watery barrier: the Bosphorus. This narrow strait connects the Black Sea in the north to the Sea of Marmara, and at its southern end the Sea of Marmara narrows down again to form the Dardanelles, connecting through to the Aegean Sea.

In Istanbul, I took the ferry to cross the glittering Bosphorus, from the Asian to the European side. I thought about the early colonisers reaching this waterway, and Bulbeck’s ideas about coastal and estuarine adaptations, and the possible use of watercraft in the Palaeolithic. It didn’t seem to me that the modern Bosphorus and the Dardanelles would have constituted much of a barrier to the early pioneers.

In fact, when I looked into it, it turned out that the Bosphorus was dry during the Pleistocene. It wasn’t until after the Ice Age that the sea level rose sufficiently to flood the Bosphorus and connect them. Boreholes drilled down through the sediments at the bottom of the strait show how and when the connection between the two bodies of water was established: the Sea of Marmara spread northwards and eventually opened into an estuary at the southern end of the Black Sea, around 5300 years ago, and the Bosphorus was formed. Interestingly, it looks like there was another, intermittently open, connection between the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea during the Pleistocene, to the east, from what is now the Gulf of Izmit.1 So even if the Bosphorus wasn’t there to cross, there may have been times when the colonisers would have got their feet wet crossing from Asia to Europe.

From the Bosphorus region colonisers could have headed northwards to the coast of the Black Sea, or continue beachcombing westwards along the Mediterranean coast, and it appears that they did both. There are a scattering of sites with Upper Palaeolithic stone tools, on or close to the Mediterranean coast, in Italy, France and northern Spain, and there are also sites dotted along both the European and Asian shorelines of the Black Sea. An important early Upper Palaeolithic site is Bacho Kiro, in Bulgaria, where a ‘pre-Aurignacian’ toolkit – with lots of blades – has been found, dating to 43,000 years ago. Moving northwards up the west coast of the Black Sea, the colonisers would have reached the great delta of the Danube, in modern-day Romania. They could have then used the waterway as a superhighway into the heart of Europe: there are many Upper Palaeolithic sites along the Danube and its tributaries. The conventional radiocarbon dates for this westwards spread across Europe suggested it took place between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago. New, calibrated radiocarbon dates for these sites suggest that this dispersal into central and western Europe happened fairly rapidly, between 46,000 and 41,000 years ago. This speedy spread across Europe may have been helped by another episode of global warming, the Hengelo interstadial.2, 3, 4, 5

Face to Face with the First Modern European:

Oase Cave, Romania

My next destination was a site along that Danube corridor. I travelled to Romania, to meet geologist and speleologist (cave expert) Silviu Constantin, who was going to introduce me to the cave where the earliest known modern human fossil in Europe had been discovered.

From Bucharest, we drove east, following the Danube fairly closely, like our predecessors 40,000 years before. We drove and drove, and eventually reached a small village in the south-western Carpathians, the name of which I cannot disclose because the exact locality of the cave was secret. A couple of stray dogs chased our car up the hill, excitedly barking, but when we stopped and got out they ran away. We were staying in the 7 Brazi (fir trees) Pensiune, high up on the hill overlooking the village.

The following morning, we met up with the team of cavers who were accompanying us – Mihai Bacin (leading the team), Virgil Dragusin and Alexandra Hillebrand – and sorted out caving gear for the trip before heading off to the cave itself. We drove through wooded valleys and past abandoned factories, and eventually turned off on to a dirt track. About a quarter of a mile later, we reached a point where the road had collapsed. We all got out to take a look, and, after hauling some large stones into the hole, decided that it was passable, and cautiously drove the cars over the roughly stopped-up breach. It held. We pulled up just around the corner from the collapsed track. The cave itself was below us in the steep-sided valley, and we scrambled down the wooded slope, lugging our equipment down to the stream bank at the bottom. Once we were down, I could see the tall, slit-like entrance of the cave, with the stream emerging from it.

This was Peştera cu Oase, the Cave of Bones. It was incredibly exciting to be standing there, in front of a place that I had read so much about. A colleague from Bristol University, João Zilhao, had been part of the team that excavated there in 2003–5, so I had heard a lot about the cave from him. Unfortunately, he was in Portugal investigating another cave, but that left me in Silviu’s capable hands – he had also been one of the excavating team, and he had dated the finds from the cave.

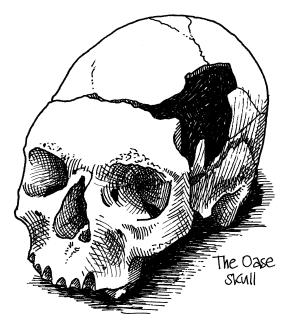

On 16 February 2002, a group of intrepid cave divers were exploring the cave. The cavers had made their way into the depths, past a duck-under and through a longer, underwater section, and up a steep ramp to an area littered with animal bones. ‘They found a human mandible, right on top of the flowstone. It was probably dug out recently by an animal. It was just sitting there, waiting for someone to discover it,’ said Silviu.

When the mandible was radiocarbon dated, it was found to be 35,000 years old, the oldest known remains of a modern human in Europe.

‘You must have been pretty excited to get that date back,’ I said.

‘I remember everyone was excited,’ said Silviu. ‘The oldest human was here, in Romania. We were proud that it was in one of our caves.’

The cave was an exciting proposition for scientists studying this period of prehistory. In 2003, an international team of archaeologists visited the cave, and discovered masses of bones – mostly cave bear, but also some other human material: fragments of a skull. These pieces were found further down the slope than the mandible, in part of the cave that was subsequently, and evocatively, named Panta Strãmoşilor (the Ramp of the Ancestors). The skull and mandible were from two different individuals.

The place where the bones were found is hard to get to now – and involves that dive.

‘The archaeologists were trying to figure out how such a massive bone deposit could come into the cave,’ said Silviu. As a geologist and a caver, he had joined the team to answer this question. He could also help with dating – using uranium series dating on stalagmites. From his investigation, it seems that Peştera cu Oase once had another entrance, allowing the cave bears access. In fact, the two galleries that lead off from the Ramp of the Ancestors both seem to have had openings in the past. Today, these entrances have collapsed, and are practically blocked off, although some small animals – such as rodents – still fall down into the cave through the sinkholes.1

The majority of the bones in Oase belonged to cave bears. There were also bones of other cave-dwellers such as wolf and cave lion, which had presumably made their dens in there at various times. However, also found in the cave were skeletal remains of distinctly non-cave-dwellers such as ibex and red deer. These could have been brought into the cave by people, but there were no signs of such habitation in the cave, nor any cut marks on the animal bones to suggest that they had been eaten by humans. That left geological processes and carnivores to explain the accumulation of bones in the cave. In 2005, the archaeologists returned to excavate the cave; they found many more bones, but also important clues as to how the skeletal remains had ended up there. Underneath a covering of stalagmite, they found a 30cm-thick layer of cave bear and other animal bones, many bearing the tooth marks of bears and wolves. This looked like a collection of bones of animals eaten by carnivores denning in the cave, as well as the cave-dwellers themselves. Under that was a layer of bones mixed with sand, gravel and cobbles, and these were sorted by size – larger bones at the top of the slope, smaller ones at the bottom, and many of the bones in this layer had rounded-off edges. These bones had been swept into this part of the cave by flooding. So it seemed that the animal bones in Oase had ended up there through a combination of cave-dwelling carnivores bringing their dinner home, and flooding.

‘So how do you think the human bones ended up in the cave?’ I asked Silviu.

‘Most probably they had been washed in.’

There were no gnaw marks on these bones, so perhaps a person, or even a buried skeleton, had fallen in through a sinkhole and then the bones had been washed further down the cave by floods.1 Nevertheless, it seems rather strange that there are only cranial remains – a skull and a mandible, and no other parts of the skeleton – but there are still a lot of bones in Oase. Perhaps the rest of the skeleton will yet be found.

I followed Silviu into the cave – wading along the stream and into the first great gallery, with Mihai, Virgil and Alexandra following behind. The roof was very high, and hung with enormous stalactites. Towards the back of this gallery were a series of pools with stalagmite edges. We followed the stream around to the left, where the roof plunged down. We were lucky that day: there hadn’t been much rain the previous weeks and days, so the water level was low enough to enable us just to keep our heads above water. In a wetter period this would have been a duck-under. Still, it was an awkward manoeuvre: under the water, the cave floor sloped away from the gap I was aiming for, and I couldn’t get a foothold. As my feet slipped, I gave up trying to walk through the gap, and swam through it instead. On the other side, I was wading shoulder-deep, hanging on to a rope to keep me close to the shallower right-hand wall. The floor of the tunnel gradually rose up until the water was just knee-high.

We all made our way along this narrow, tunnel-like part of the cave. Sometimes the floor dipped down and we would plunge in up to our chests again. Eventually, we reached a wider part of the tunnel, but the roof sloped down and down until it touched the water: this was the siphon, and the end of the line for me. I would have had to dive to get to the Ramp of the Ancestors. It was frustrating in a way, but I had known that I would only be able to get this far. I still felt privileged to have come so close, and to have explored the cave where Europe’s earliest modern human had been found. Silviu and I sat down on a convenient stalagmite and I asked him about excavating in the cave. It sounded arduous and difficult – getting to the site was one thing, taking in tools and bringing back bags of sediment and bones, through the siphon and through the duck-under another altogether – but the results had been worth it. When the skull had been dated, it was even older than the mandible: around 40,000 years old. And there were some things about the skull and mandible that seemed a little odd.

Leaving Oase, Silviu and I drove back to Bucharest, where I would be able to see the skull and mandible. We had travelled close to the Danube on the way out to Oase, but on the way back we took a route through the beautiful wooded gorges of the Carpathians. Where the gorges opened out into valleys, fields were visible in which people were cutting hay and heaping it on to three-legged wooden frames to make stacks. The haystacks varied from field to field and village to village. Some were tall and thin, others squat and conical. We slowed down to pass a heavily laden hay cart pulled by two horses.

The centres of the villages were often lined with low, terraced cottages, but on the outskirts there were more often than not massive, ugly tower blocks. These buildings seemed so incongruous among the fields. ‘Why build blocks of flats in villages?’ I asked Silviu. ‘They were built by Ceauşescu,’ he said. ‘He wanted to create more land for farming.’ ‘But it seems like there’s plenty of land,’ I suggested. ‘Yes. There is. Ceauşescu wanted to destroy the villages.’ It was strange to think that it really wasn’t that long ago – 1989 – that Ceauşescu had been removed from power. Romania was a country in recovery.

Silviu told me about how he had travelled around the countryside as a young man. He recounted how, if he’d got stuck for somewhere to stay overnight, he would find a barn and sleep in the hay. He usually looked for someone to ask beforehand, and had often been invited in to dinner. ‘People treated the occasional backpacker as a traveller: to be given hospitality,’ he said. ‘Now they want money. They think tourists have money and they want some of it.’ Silviu was worried about the people and the countryside being spoilt by tourism. He liked the wilderness.

‘What would this landscape have looked like 40,000 years ago?’ I asked Silviu.

‘I don’t know,’ he said, and paused for thought. ‘It would have been [Oxygen Isotope] Stage 3. So – colder than now. And wetter summers. Like – perhaps Norway today, at the coast; maybe like Bergen.’

I tried to imagine the hunter-gatherers in the foothills of the Carpathians, dressed warmly against the cold, in a country with red deer, ibex, wolves and cave bears. Although cave bears are long gone, there are plenty of brown bears roaming Romania today: nearly half of all European bears are in the Carpathians. Some hunting of bears goes on today; indeed, one restaurant in Bucharest even had ‘bear paw’ on the menu. There were times when I was truly glad to be vegetarian.

The following day, I visited Silviu in his natural habitat at the Emil Racovita Institut de Speologie in Bucharest. He brought a series of cardboard boxes into a lab next to his office and we carefully unpacked some of the Oase bones. There were pieces of animal bone embedded in speleothem – a real gift for a geologist like Silviu who could date the stalagmite, and therefore the bone. He also brought out a huge and formidable looking cave bear skull. And then there were the human remains: the mandible and the skull.

Again, these were quite clearly modern human. The skull was globular in shape, without any of the more obvious features of an archaic skull, like big browridges, or a protruding occiput at the back of the head. The jaw was quite gracile and modern-looking too, with a definite chin. But there were some oddities – particularly in the mandible or jawbone. The chin was very straight, the ramus (the part of the mandible ascending up to the jaw joint) was very wide, and the mandibular foramen (the hole on the inside of the ramus where the nerve supplying the lower teeth enters) was a little strange. Then there were the teeth, set in a very wide arc in the mandible, and with absolutely enormous wisdom teeth. These molars are usually smaller than the ones in front, but in the Oase jaw they were huge.1,2 I had read about these odd features in the scientific articles announcing the discovery and dating of the Oase bones, but it was something entirely different to hold the actual bones in my hands and look at them myself.

Now, everyone is unique and we all have ‘anatomical traits’ – little variations on a theme – in our bodies and our bones. In our skulls, some of us may have one hole for a particular nerve, where others have two or three. We might have little islands of bone, or ‘ossicles’, embedded in the zigzag joins or sutures where the plates of the skull come together. Some of these traits are genetic, whereas others appear during our lifetimes, and might be related to diet – or other things we do to our bodies. For instance, lumpy bits of bone inside the ‘external auditory meatus’ – the bony part of the ear canal – can be caused by swimming in very cold water. But, like skull shape and size generally, we’re not sure about how or why some of these traits occur, and the various influences of genes and environment. It’s all part of that great question in developmental biology: how are our bodies shaped by our genes and our environment?

Having said all that, however, there are traits that do at least seem to hark back to an ‘earlier’ form. If you were being unkind, you might call them ‘throwbacks’. If you were a bit nicer about it, you might think of these characteristics as echoes of evolutionary history, glimpses of where we’ve come from. And those odd traits in the Oase jaw seem to fall into this category: archaic features. But could this be more than just an echo of a more distant evolutionary past in these 40,000-year-old bones? Is it possible that, instead, the Oase bones show a mixture of modern and archaic traits because that person was a mixture of a modern and an archaic human – some sort of hybrid? This isn’t such a preposterous idea, because, when modern humans started making their way into Europe, someone else was already there: the Neanderthals.

As we have seen from the archaeology and fossil record of East Asia, ours was not the first human foray out of Africa. A series of archaic human species made the leap before us.

In a review article that appeared in Science in 2003, Ann Gibbons wrote: ‘The long-legged, relatively big-brained hominin called Homo erectus has long been considered the Moses of the human family – the species that led the first exodus out of Africa more than 1.5 million years ago.’3

The biblical analogy is great. I can imagine that striding, big-browed man leading his people out of Africa, across the Red Sea, but it’s a sleight of pen in two ways. Firstly, there’s a wry and unwritten ‘but of course it wasn’t like that’, as we all have this tendency to promote our ancestors to heroes and imagine their lives as epic struggles against adversity, winning through so that we could be alive today. And secondly, Ann Gibbons goes on to write about Homo georgicus, one of the recent and somewhat cheeky surprises in European palaeoanthropology. The three paradigm-nudging and diminutive fossil skulls were recently discovered in Dmanisi in Georgia, and dated to 1.75 million years ago. Then another small skull was found in Kenya, dating to about 1.5 million years ago – perhaps belonging to a particularly small population of Homo erectus, perhaps linked with the Georgian hominins. The Kenyan skulls were the same age as another famous fossil: Turkana Boy. This young man, with a largish brain, is sometimes classified as Homo erectus, sometimes as Homo ergaster. (Remember that the world of palaeoanthropology is interpreted differently by ‘lumpers’ and ‘splitters’ – see page 3.)

Fossils can be extraordinarily slippery when you’re trying to pin a species name on them. The Kenyan and Dmanisi skulls are no exception. They all look a bit like a small Homo erectus without browridges, but also bear similarities to another, earlier hominin species, Homo habilis. Although the discoverers of the Dmanisi skulls claim that they warrant a new species name, Homo georgicus, most researchers place the skulls in Homo erectus. So maybe erectus was the first hominin to get out of Africa after all.3

Georgia lies west of the Caspian Sea, but it is hard to know whether it really counts as part of Europe or Asia. Certainly, Dmanisi was sidelined when another, intriguingly ancient fossil, this time from the Sierra de Atapuerca, in northern Spain, was reported as ‘The first hominin of Europe’. It dated to 1.2 million years ago, and its discoverers suggested that it was Homo antecessor (a category that some lump into Homo heidelbergensis).4

By about 300,000 years ago, Homo heidelbergensis in Europe had morphed into Neanderthals. And when modern humans got to Europe, these other hominins, their distant cousins, were still around in the landscape.5,6

The first fossil of these ancient Europeans was found in 1848, in Gibraltar, but nobody paid it much attention. The bones that gave the species its name were found in 1856 in Germany, near Düsseldorf – in the Neander Valley, or Neanderthal. The valley was being quarried for limestone, and workmen clearing out mud from caves in the cliffs prior to quarrying found what they thought were cave bear bones. But a local teacher recognised that they were human and collected them up.7

The following year, rather bravely for the time, Professor Schaafhausen of Bonn University published a report on the skull and bones from the Neander Valley, saying that they were normal – non-pathological – but seemed to be from an ancient inhabitant of Europe as the remains were found alongside bones of extinct animals. This interpretation was challenged by Professor Mayer, also at Bonn, who said the bones were probably much more recent, probably those of a Russian Cossack dying from rickets who had crawled into the cave, with great browridges from frowning in agony. But a few years later the find had been widely published, and there was a growing consensus that the bones were very ancient. The Irish anatomist William King proposed that the skeleton should be given a new species name: Homo neanderthalensis. It was the first known species of a fossil human.7,8,9

Since the discovery of the first Neanderthal fossil more than 150 years ago, several thousand bones have been found from more than seventy different sites. And there are over three hundred sites where Neanderthal stone tools have been found.

Neanderthal characteristics start to appear in European Homo heidelbergensis. For instance, the Sima de los Huesos specimens from Atapuerca, which are over 350,000 years old, already have some ‘Neanderthal’ features such as protruding faces and gaps behind their wisdom teeth, as well as a characteristic shape of the browridge, and a ridge across the back of the head: the ‘occipital torus’.10 By about 130,000 years ago, ‘classic’ Neanderthals, with full-blown features, lived right across Europe – and beyond.11 Their territory extended from Portugal in the west to Siberia12 in the east, from Wales in the north to Israel in the south. And they persisted in some parts of Europe and western Asia until less than 30,000 years ago – after modern humans had arrived in Europe.

Given that we now know so much about Neanderthals, there are still many questions about their disappearance. Although there is no evidence of Neanderthals and modern humans actually living in precisely the same places at the same time, there was certainly a period when both species were present in Europe. It used to be thought that this period of overlap lasted around 10,000 years, but new calibrated radiocarbon dates suggest that the overlap was shorter: about 6000 years in north and central Europe, and perhaps only one or two thousand years in western France.13 But why did the Neanderthals disappear? Did we kill them off or out-compete them? Or perhaps they are actually still around – could Neanderthals have been assimilated into the expanding modern human population as it flowed westwards across Europe?

There are certainly some researchers who think so. They put forward specimens – mostly skulls – like Oase and Cioclovina from Romania, the Mladeč fossils from the Czech Republic and the Lagar Velho skeleton from Portugal1 – as physical evidence for interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans. Palaeanthropologists João Zilhao and Erik Trinkaus suggest that archaic traits in these fossils are not just ‘throwbacks’: they may be evidence of Neanderthal genes in the early modern human populations of Europe.

Neanderthal Skulls and Genes: Leipzig, Germany

So I made my way to Germany, not to the Neander Valley, but to the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, where I had arranged to meet Dr Katerina Harvati, who had recently analysed the Cioclovina skull. Katerina met me on the other side of the revolving door at Max Planck, and we walked into an enormous space, some three floors of atrium with light streaming in through glass walls on two sides. Stairs and ramps to the upper floors seemed to float in the air. Katerina led me up to the labs on the second floor, where she was going to show me CT scans of the Cioclovina skull.

But my attention was first drawn to a composite skeleton, put together from casts of fossil bones from different sites, standing in the corner of the lab. It was the first time I had laid eyes on a complete, assembled Neanderthal skeleton, and it was interesting to see just how stocky he looked. The ribcage flared out at the bottom, quite different from the modern human chest shape. Individual bones were generally quite similar to modern human bones, but nonetheless very rugged.

‘We can tell from their body form and proportions that Neanderthals were showing some level of cold adaptation: they were stocky, with short limbs,’ said Katerina.

But how much of an advantage would this have given them, compared with modern humans?

‘It has been calculated that the advantage would be – perhaps not as great as we originally thought – maybe the equivalent of one business suit.’

It didn’t sound that impressive. Cultural adaptations, like clothing and use of fire, must have been more important to the Neanderthals’ survival in Ice Age Europe.

But the most ‘different’ part of all the Neanderthal skeleton was the skull. Neanderthals have very long, low skulls, whereas modern human human crania are much rounder. Neanderthal faces are big: they have massive browridges, large, goggly orbits (eye sockets), large nasal openings and projecting, prognathic jaws.

So what about this Cioclovina skull that had been suggested to be a Neanderthal/modern human hybrid? The skull itself had been discovered in the cave that gives it its name in southern Romania, in 1941 – during phosphate mining – and had recently been radiocarbon dated to about 29,000 years old. The skull was really just a braincase: most of the face was missing. Although its general shape was definitely modern, some researchers had suggested that the shape of the browridge and the back of the skull were Neanderthal-like.1

Obviously, before you can confirm or reject a claim that a skull represents a hybrid, you have to have an idea of what a hybrid might look like. Is it likely to have an even mix of features from each parent? Or might it be mostly like one parent with just a few features from the other? Katerina had looked into the features of hybrids in other primate groups and she found that a common feature of hybrids seemed to be a size change – either bigger or smaller – than would be expected from the parent populations. Some hybrids – like a gibbon–siamang cross in Atlanta Zoo, and hybrids from different macaque and baboon species – looked anatomically like a mixture of the two species they came from. It also seemed that hybrid populations tended to be more variable than the parent species, and also had rare anomalies popping up more often than usual.1

So Katerina had analysed the Cioclovina skull to see if it showed any of these signs of being a hybrid: an appreciable size difference, a mixture of features, a high level of variability, or any strange anomalies. But she had also measured the skull so that she could compare its size and shape with those of other modern human and Neanderthal skulls. Describing features in skulls, even measuring them, is fraught with problems, as I had seen so vividly in China, but Katerina had also used a technically sophisticated and perhaps more objective approach to the problem of comparing skull shape and size.

The first step was to convert a real skull into a mathematical model, a cloud of points in 3D space that described the shape and size of the skull, using features or ‘landmarks’ that could be recognised on any skull. Rather than measuring a skull with calipers to get distances and angles, Katerina showed me how she had captured the 3D shape and size of skulls in two ways: using an electronic digitiser and CT scans. The digitiser was an elegant piece of equipment – an articulated arm ending in a stylus that could be placed on the surface of a skull – and points could be captured in 3D space, with x, y, z coordinates. It was a piece of apparatus that was widely used in design and engineering – and was now beginning to be applied to the study of old bones. 3D coordinates could also be taken from detailed CT scans of skulls, which would allow points on the inside as well as the outside of the skull to be recorded.

Having captured and quantified all that information, Katerina could then compare different skulls, and she did this in the context of variation among different primates.

‘The difference between Neanderthals and modern humans is not similar at all to the differences that you would find between subspecies of primates living today,’ she said.

‘It is much more similar to the distances you’d find between closely related species.’

‘So you can be absolutely sure that Neanderthals are a separate species?’ I asked.

‘Yes, that is what I’d say. They are too different to be another population or even a subspecies of modern human. They were our sister species. Closely related – but a different species.’

This seemed to refute the multiregionalist idea that all species since Homo erectus have essentially been one.

‘So what about Cioclovina?’ I asked. Katerina showed me a 3D computer model of the Cioclovina skull, based on CT scans that had been done at a local hospital. She spun the model round on the screen, and pointed out the relevant features. The browridge was big, but it was broken in the middle, unlike the uninterrupted ‘monobrow’ of Neanderthals. The occipital bone at the back of the skull did bulge out, and the nuchal line where neck muscles attached was well marked, but not really Neanderthal-looking. There didn’t seem to be anything unusual about its size, nor were there any odd anomalies in the skull.

So what about the results of the shape analysis? Katerina had compared the 3D ‘landmark configuration’ of the Cioclovina skull to Neanderthal and modern human (including Upper Palaeolithic) skulls. Using different sets of statistical analyses to make the comparisons, Cioclovina always came out closer to modern humans.1

‘From my analysis, I wasn’t able to see any resemblance to Neanderthals,’ Katerina told me. ‘There is no evidence to support the claim that this is hybrid. It actually turns out to be very typically modern human in its anatomy.’

It was clear that Katerina couldn’t wait to look at the other proposed hybrid specimens, like Oase. She was open-minded about what her results meant, and what she still might find.

‘Of course this doesn’t mean that hybridisation didn’t happen. It could have happened and we just haven’t found the hybrids yet. Or, some of the other proposed hybrids that I haven’t examined yet might fit the criteria. Or it could be that it was so rare that it hasn’t left a trace in the fossil record. And the genetic evidence to date suggests that if admixture happened, it was so low that it was really not significant in an evolutionary sense.’

Indeed, it wasn’t just the shape and size of Neanderthal bones that was being studied in Leipzig, it was genes as well. In 1997, a team of scientists led by Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute published the first analysis of DNA from an extinct human. They had managed to extract mtDNA from one of the original fossils from the Neander Valley. Pääbo chose to look for a non-coding, fast-mutating section of mitochondrial DNA that had already proved useful in studies into evolutionary relationships between living species.

Getting DNA out of an ancient bone was always going to be a huge challenge – DNA starts to fall apart after death – but Pääbo and his team had hoped that some tiny fragments might still be there. The extraction was done in a sterile room, to try to reduce the possibility of contamination with modern DNA. The bone sample was ground into powder and then the sample was treated to amplify up any DNA – by getting any fragments to make copies of themselves. Then the sequencing could start, and the results were quite stunning: when they compared the Neanderthal sequence with the equivalent mitochondrial DNA sequence from nearly 1000 modern humans, they found that it was distinctly different. The modern human mtDNA sequences differed from each other by an average of eight different base pairs out of almost four hundred. But the Neanderthal sequence had an average of twenty-six base pair differences compared with the modern human samples. This difference suggested that Neanderthal and modern human mtDNA had been evolving along separate pathways for about 600,000 years. Although this seems a very long time ago, compared with the dates of the earliest known Neanderthal (about 300,000 years ago) and the earliest known modern human (about 200,000 years ago) it still makes sense, as the lineages would have started to diverge within an ancestral population of Homo heidelbergensis.2

This result seems to support the theory of a recent African origin of modern humans, and a replacement of any earlier human populations. In contrast, the multiregional hypothesis suggests that archaic populations in Africa, Europe and Asia developed into modern human populations. A halfway house theory has modern humans originating in Africa, then spreading into Europe and Asia and interbreeding with existing archaic humans.

Pääbo’s findings suggested that the mitochondrial DNA lineages, at least, had separated (and stayed separate) hundreds of thousands of years before modern humans appeared in Europe. Even if you ignore the timings, then the multiregional model with hybridisation suggests that Neanderthals should be genetically closest to modern Europeans, but there was no evidence of this in the mitochondrial DNA: the Neanderthal sequence was equally different from all modern humans across the globe. Another study compared ancient DNA extracted from two 25,000-year-old European modern human fossils, and found that the Cro-Magnon mtDNA fell in the modern human range of variation, and was very different from the Neanderthal sequences.3

Looking at mtDNA variation as well as modelling the population expansion of modern humans in Europe, researchers in Switzerland came up with a maximum interbreeding rate between the two populations of less than 0.1 per cent. Statistically, this is so low as to be practically non-existent, and the Swiss scientists go as far as to say that this suggests the two species were biologically separate – and could not produce fertile offspring even if they had seized upon the chance to have sex with each other.4

So do these mtDNA results represent definitive evidence that the Neanderthals could not be counted as among the ancestors of modern Europeans? Well, they certainly seem to point in that direction, but, actually, it’s impossible to completely rule out any hybridisation between modern and archaic populations. Neanderthal genes could have entered the human gene pool, but those lineages might have died out, leaving no trace of them today. And what if only Neanderthal men, not women, had interbred with the incoming modern humans? That wouldn’t show up in the mitochondrial DNA – which is inherited only from the mother. So although these Neanderthal mtDNA studies are amazing, and suggest that hybridisation didn’t happen, they can’t rule it out. So would it be possible to probe further, to go after more Neanderthal DNA – perhaps nuclear DNA?

When Svante Pääbo was interviewed for Science magazine after the publication of the Neanderthal mtDNA paper in 1997, he was very pessimistic about the chances of anyone ever managing to recover and sequence nuclear DNA from Neanderthal bones.5 But just over a decade later, I was visiting his lab at the Max Planck Institute – and they were doing just that.

The genetics labs were just along the (very beautiful, sky-lit, gently curving) corridor from the bone lab. The Institute felt like a modern monastery, with an all-pervading calm and scholarly atmosphere. But instead of monks painstakingly copying out biblical passages, scientists were locked away in their high-tech scriptoria, sequencing the Neanderthal genome.

I met up with Ed Green, one of the geneticists hard at work on the Neanderthal Genome Project. Ed had brought along some casts of the original fossils from which DNA had been extracted.

‘How do you go about trying to extract DNA from these fossils?’ I asked Ed.

‘Well, the first thing is to find the fossil that has ancient DNA that can be extracted. Then the way it’s done is to simply to take a dentist’s drill, drill a bit, get some bone powder, and then use a standard extraction method where you bind DNA to silica beads.

‘Then the really fun part begins – trying to sequence this DNA, and see what is there. Is this DNA from the individual that owned this bone originally? Or DNA from bugs that have crawled into the bone since then?’

‘And presumably there’s quite a lot of modern human DNA knocking around as well – from the archaeologists who excavated them,’ I suggested. Ed agreed. He was very keen to encourage archaeologists to excavate fossils in a ‘sterile’ way today, but there were many bones that had been discovered decades ago, and handled by scores of archaeologists and curators.

The team had looked at more than seventy Neanderthal fossil bones, and tested them first to see if they were likely to contain any usable DNA by checking the condition of other organic molecules: amino acids. Six of the specimens had good levels of these protein building blocks, so there was a good(ish) chance that some DNA might be in them as well. They went on to extract DNA, but, always aware that this genetic material could come from modern people, they checked for contamination before going any further.

A sample from a fragment of Neanderthal bone from Vindija Cave in Croatia looked particularly promising. ‘Luckily for us, this shard of bone was not interesting enough morphologically to have been handled and looked at a lot – so this guy is nearly free from contamination by modern humans,’ said Ed.

So the geneticists chose to try out DNA sequencing procedure on the extract from the Vindija fossil. This technology is advancing at an astonishing rate. Inside insignificant looking white boxes in genetics labs there are small trays holding hundreds of wells of DNA fragments. And the genetic material they are dealing with is very fragmentary: over time, long stretches of DNA that start off with millions of base pairs become broken and broken again into short sections of just a few hundred or tens of base pairs each. So the process involved sequencing those fragments and then virtually sticking them back together. New technology meant that many different fragments could be sequenced at the same time. ‘The throughput for DNA sequencing is hundreds of times more than it was just three or four years ago,’ Ed told me.

He explained the sequencing method in a very visual way (considering you can’t actually open up the box and watch it in action). In each well, there were many copies of one strand of DNA, and the machine worked out the sequence by ‘asking’ each strand what nucleotide base (A, C, T or G) was next. It did this by flowing a solution over the wells containing each base in turn. If the ‘next’ base was T, the solutions of A, C and G would flow over uneventfully. When the solution containing T was introduced, enzymes would grab the base and at the same time emit a flash of light. This is called ‘pyrosequencing’. ‘Every flow, you’ve got different wells lighting up, like a firework display,’ said Ed. Every time a nucleotide solution passed through, some of the wells would answer ‘yes’ by emitting a flash. The machine cycled on and on, until all the strands in all the wells had been sequenced. This technique can read segments of 100–200 nucleotides in length: perfect when you’re looking at tiny fragments of an ancient genome.

Many of the sequences had turned out to be bacterial, but that’s exactly what the geneticists expected. But comparing the sequenced fragments with human, chimpanzee and mouse genomes, a good percentage of them looked primate. Then came the work of assembling those sequenced fragments into longer pieces. Eventually, if they managed to extract enough fragments, the geneticists would be able to sequence the entire Neanderthal genome.6

Analysis of Neanderthal DNA should be able to cast light on many areas of enquiry, not only the question of hybridisation. By comparing the differences between Neanderthal and modern human DNA, the geneticists can estimate the time of the ‘split’ between the lineages. At the moment, in Leipzig, that’s looking as though it happened some time around 516,000 years ago. This is older than the split suggested by fossils, at about 400,000 years ago – but that’s unsurprising. The genetic split would have happened in a population that was still ‘together’.

This is ground-breaking science, so it’s not surprising that there are still problems that need to be ironed out. And probably the most tricky one is that problem of contamination with modern DNA, which could skew results. Pääbo’s Leipzig lab isn’t the only place where Neanderthal genome sequencing is going on. A team led by Edward Rubin, in California, are also at it – and they published their first chunk of Neanderthal sequence in the same week as Pääbo’s team. But they came up with different results and a different – even earlier – prediction for the divergence of Neanderthals and modern humans, of around 706,000 years ago.7 So it seems that, even with all that careful screening, some contamination may have crept in, explaining the earlier dates coming out of the Leipzig lab.8 With each lab acting as a check on the other, though, the scientists hope that they will be able to overcome these teething problems.9 The Californian dates may seem very early indeed, but it’s important to remember that this is the predicted date of divergence of the mtDNA lineages, not of the actual populations. Based on this genetic data, Rubin’s team estimated that the population split happened about 370,000 years ago, which is quite a good match with the fossil data.

Another potential application for ancient DNA is in identifying bone fragments that are too small to characterise on the basis of size and shape. In fact, this has already been applied to fossils from at least two sites. A child skeleton from Teshik Tash in Uzbekistan has often been held up as the most easterly example of a Neanderthal, but some have disputed its credentials. Even further east, bones and teeth from Okladnikov Cave in Siberia, found alongside Mousterian tools, were too broken up for it to be decided if they were modern human or Neanderthal. Genetics to the rescue, then. Scientists working in labs in Leipzig and in Lyons independently extracted and analysed the mtDNA from the bones from both sites. The results showed that the Teshik Tash child had Neanderthal mtDNA, and so did two of the bone fragments from Okladnikov.10 This study was very significant: it hugely extended the known range of Neanderthals to the east, right into Central Asia. Maybe they even got to Mongolia and China. Genetic analysis is clearly an exciting addition to the toolkit of the Palaeolithic archaeologist.

There is also exciting potential for finding out – at some point in the distant future, when we know a lot more about the functions of genes in us and other animals – more about Neanderthal biology.6 But even now we know that at least some Neanderthals possessed a version of a gene that probably gave them red hair. The gene in question is melanocortin 1 receptor (or ‘mc1r’). In modern humans today, mutations that impair the function of this receptor gene produce red hair and pale skin. A team of geneticists managed to extract DNA – including part of the mc1r gene, from two Neanderthal fossils, one from Spain and another from Italy. Both fossils contained a mutated version of the mc1r gene, different from any of the variants seen in modern humans. To see what effect this gene would have, scientists inserted it into cells in the lab and found that it had a partial loss of function – like the other variations in the mc1r gene that produce red hair in humans today.11 It is important to note that this is a different mutation from that in modern human redheads. It doesn’t imply any genetic mixing between Neanderthals and modern humans, and it certainly doesn’t suggest that the redheads among us are Neanderthals!

Another particular gene that has been identified in Neanderthals is FOXP2. This is a gene that has two specific differences in humans compared with other living primates. People missing out on those human-specific changes to FOXP2 have problems in both producing and understanding speech. Analysis of FOXP2 in living people suggested that it appeared and swept through the human population about 200,000 years ago, which seemed to fit quite well with the appearance of modern humans in Africa. It suggests that ‘modern’ language and symbolic behaviour are uniquely human attributes, with a biological basis. Eric Trinkaus took issue with this interpretation. He argued that there was evidence for symbolic behaviour in the Neanderthal archaeological record, with intentional burial, for instance. And he found it hard to imagine how complex subsistence strategies would have appeared – from around 800,000 years ago – without complex social communication. And yet the ‘human’ version of FOXP2 was initially estimated to have arisen well after the split between modern human and Neanderthal lineages.12 But a recent DNA study of two Spanish Neanderthal fossils showed that they both carried the ‘human’ form of FOXP2.13 For Trinkaus, this showed that the ‘much maligned Neanderthals’ had a degree of human behaviour that was reflected in the archaeological record but that he felt had often been played down. But how can we explain the same version of FOXP2 existing in both modern humans and Neanderthals? Either it is much older than the earlier studies suggested, and was present in the ancestors of modern humans and Neanderthals, or it has passed from one population to the other by gene flow. The latter seems very unlikely as no other genetic studies to date had produced any evidence of gene flow.13

But what about the ambitious Neanderthal Genome Project? Was there any evidence for hybridisation emerging from the nuclear DNA? The key to looking for evidence of hybridisation was to concentrate on genes or other bits of chromosomes that are specific to modern Europeans (and this is a tall order as most genetic differences are shared between populations across the globe rather than being specific to one area), keeping an eye out for these sequences in the Neanderthal genome. If any European-specific DNA sequences were found in Neanderthals, this would strongly imply that there had been some sharing of genes between Neanderthals and modern humans in Europe.

When I visited the Max Planck Institute in the early summer of 2008 Ed told me that they had managed to sequence about 5 per cent of the Neanderthal genome. I asked him a difficult question, considering that the Neanderthal Genome Project was still such a long way from completion: ‘If chimpanzees are about 1.3 per cent different from us, in terms of the sequence of DNA, do you have a feeling for how different the Neanderthal genome is going to be from ours?’

‘Yes, we do,’ he replied. ‘It’s looking about ten times closer than the chimpanzee. But Neanderthals are so closely related to us, it’s hard to speak in terms of percent differences. It really depends on which Neanderthal and which human you’re talking about.’

‘And have you seen any suggestion at all of hybridisation with modern humans?’ I asked.

‘No. There’s no evidence to date of any hybridisation between modern humans and Neanderthals,’ he replied. ‘But by the end of the summer we should have 65 per cent of the Neanderthal genome, so we’ll be able to give a much more definitive answer then.’

This question of what happened when modern humans walked into Neanderthal territory was fascinating. I asked Ed what he would have done if he’d met one of our cousins.

‘If I came face to face with a Neanderthal, the first thing I would do is ask for a DNA sample,’ said Ed, ever the scientist.

So far, then, Neanderthal genetics has shed light on how far this ancient species ranged across Europe and Asia, has shown that they possessed the same ‘language gene’ as modern humans (although it must be stressed that the development of language cannot be linked to just one gene), and that some of them had red hair. And, bearing in mind that there was still a lot of genome left to sequence, there was no evidence – yet – for any mixing between Neanderthals and modern humans in Europe. (Nearly a year after I visited Leipzig, Svante Pääbo announced the completion of the first draft of the Neanderthal genome – 63 per cent of it, over three billion bases – at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Chicago. There was still no sign of interbreeding with modern humans.)14

But it’s also important to remember that the conclusions from genetic studies like this can never rule out any hybridisation. Perhaps it’s just that Neanderthal lineages have not survived to the present day, and maybe some Neanderthals had modern human genes – just not the ones whose genomes were being sequenced.

Does this make the whole endeavour futile? Far from it. If there is no evidence of mixing, then we can at least say that hybridisation didn’t happen at a level that we could consider to be significant, and so it cannot explain the apparent disappearance of Neanderthals from the fossil and archaeological record: they cannot have been absorbed and assimilated into ‘modern’ populations.

Thus far, all the genetic studies suggest that any hybridisation was, at the most, insignificant. And, actually, when you take a closer look at when and where Neanderthals and modern humans were living in Ice Age Europe, this makes some sense. There are only two areas where the dates for modern humans and Neanderthals actually coincide: in southern France and in south-west Iberia, in the period between 25,000 and 35,000 years ago.15 Even then, they could have missed each other by hundreds or thousands of years, so the opportunities for inter-species sex would have been extremely few and far between anyway. So it’s not really surprising that no ‘Neanderthal’ genes have been found in the modern gene pool – or vice versa.

So that means that the Neanderthals – whether or not rare liaisons led to hybrids whose existence has now been expunged from the modern gene pool – really did disappear. But why did the Neanderthals, who had been living in Europe for hundreds of thousands of years, fade away when modern humans arrived on the scene?

I needed to look more closely at the archaeological evidence: was there any difference in the way modern humans and Neanderthals were subsisting in their environment? Was there anything that could have given modern humans ‘the edge’ in Europe?

Treasures of the Swabian Aurignacian: Vogelherd, Germany

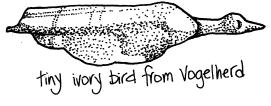

In a complete contrast to the ultra-modern Institute in Leipzig, I next visited the medieval university town of Tübingen. I walked up cobbled roads to a castle where I passed through a great arch into a courtyard, then on past a fountain and up stone steps, then turned a corner to enter the Department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology. At the end of a corridor plastered with posters of wonderful carved animals and birds, I found Professor Nick Conard in his office.

Nick’s office was lined with red cupboards on one side, dark wooden bookshelves on another, and wooden filing cabinets. There were two desks, each piled high with papers and books, and in one corner was a large grey safe with a map of the Swabian Jura hanging on it. Nick had spent years excavating sites around Tübingen, where he had discovered evidence of the earliest modern humans in Europe. But it wasn’t just stone tools that he’d found: there had been some rather wonderful pieces of art and musical instruments. And he had some of them in the safe. I had to look away while he found the key and then started bringing small cardboard boxes over to a low table, where we sat down to open the boxes of treasures.

The first object Nick took out, dating to around 35,000 years ago, was an ivory flute. It was discovered in 2004, at a cave site called Vogelherd, lying beneath two other flutes that had been made from hollow swan bones. The ivory flute had taken much more craftsmanship, though: it had been carved out of a mammoth tusk, then split to hollow out the inside, and joined back together with something like birch pitch. There was a row of incised notches down each side, crossing the join, perhaps made to help when putting the two halves back together.

The ivory flute had been smashed up into fragments, which archaeologists had found and carefully pieced back together; the notches had also helped the archaeologists when it came to reconstructing the flute. Nick explained that, using mammoth ivory, the instrument-maker wouldn’t have been constrained by the dimensions of a hollow bird bone and so could make a much larger, longer instrument. But it also seemed to be an exhibition instrument – designed to show off the technical skill of the instrument-maker. Nick had been completely taken by surprise by this discovery. They had found mammoth ivory carvings in Vogelherd before, but this was the first indication of music that had emerged from the site. The three small flutes represented the first real evidence of music – anywhere in the world. Nick had a replica of one of the swan-bone flutes, which I tried to play with less than impressive results, not being any sort of musician. But I could at least get a series of notes out of it. More accomplished musicians have tried and produced music that sounds quite harmonious to the modern ear, with tones comparable to modern flutes or whistles.

Opening the other boxes, Nick brought out some finds from the 2006 digging season at Vogelherd, and from the nearby cave of Hohle Fels – beautiful things nestled into cut-to-fit shapes in foam inside each box. Nick lifted out a tiny ivory mammoth, just 3cm long. It was carved in the round, with naturalistic detail, its trunk hanging down and curving over to the right, and there was a tiny spike of a tail. The hind legs were shorter than the front. It seemed perfectly proportioned. The bottom surfaces of the feet were scratched in a crisscross pattern.

Then there was a lion carved in relief, again in ivory, with hatching along its back. It had a long body, and its hackles were raised. And a tiny, beautiful bird. The body of the bird had been discovered in earlier digs, and there had been much speculation about it. Was it a human torso? But then the archaeologists had discovered the head and neck – a minute fragment that could so easily have been passed over. But it fitted the body, and, suddenly, there was a bird, perhaps a duck or a cormorant, with its neck outstretched. Finally, from another small box, Nick carefully lifted out a minute lion-man. Standing just over 2cm tall, he looked like a miniature version of the famous lion-man from Hohlenstein-Stadel, near Ulm – around the corner from Hohle Fels. All of these objects dated to more than 30,000 years ago.1

But there was one more surprise. Nick opened a long box, and inside it was a long, smooth piece of stone, unmistakably carved into the shape of a penis, with the foreskin and glans carved into it at one end. We contemplated this bizarre object. Was it a hammer stone, carved in a phallic shape as a joke? Or could it be that this stone had a functional use more related to its shape? Nick was quietly amused by the find. It suggested that the people of the Swabian Aurignacian had, at the very least, a healthy sense of humour, and perhaps an even healthier sexual appetite.

The art of the Swabian Jura was fascinating, and this really is the earliest evidence of something that we can properly appreciate as art. I had seen pierced shells and ochre ‘crayons’, leaving us guessing what was drawn with them, but here were carefully executed carvings of animals, and strange therianthropic beasts – men with heads of lions. Nick said that the styles of these Aurignacian carvings were similar across different sites in the Swabian Jura, although there were many different themes. It seemed to be a time of some artistic experimentation. But recurring imagery like the lion-men from Hohlenstein-Stadel and Hohle Fels also suggested very strongly that they were made by people from the same cultural group in the Lone Valley. Many different ideas have been put forward about the meaning and function of these artefacts: some have suggested that they indicate hunting magic, and the therianthropic figures in particular have been linked to shamanism. For Nick, the discovery of the tiny waterfowl carving challenged previous interpretations of Aurignacian carvings from the Swabian Jura as representing fast and dangerous animals, with whom Palaeolithic hunters may have identified.1

‘I think the combination of these symbolic artefacts, ornaments, figurative representations and musical instruments, shows us these people have the mental sophistication of ourselves, the same creativity that we have,’ he said. ‘And we can even get insights into the system of beliefs. For instance, the examples of human depictions combined with lion features show that, at least in their iconography, they were engaging in transformation: people having a connection with the animal world, being depicted as mixed animal/human figures.’

But how could these small ivory carvings hold any clue to the survival of modern humans – and the demise of the Neanderthals? Well, certainly the Neanderthals, however intelligent and whether or not they had language like us, never produced anything like the objects found at Vogelherd. I asked Nick about the differences between modern humans and Neanderthals, and it became clear that he thought culture had played a key role in the expansion of modern human, and contraction of Neanderthal, populations, during the late Pleistocene.

On their own in Europe, the Neanderthals seemed to have been getting along just fine.

‘The Neanderthals were the indigenous people of the area. They had very sophisticated technology, certainly command of fire, and knew how to get along in their environment. They had everything 100 per cent under control, and they were doing very well,’ said Nick.

‘So if they were so good at surviving in Ice Age Europe, why did they disappear?’ I countered.

‘Well, I would approach that question from an ecological point of view. If you have one organism occupying a niche, it’s going to stay there until something drives it out of its niche: either environmental change that makes it impossible to occupy the area, or another organism coming in and competing for resources.’

‘So you’re saying that modern humans were that competing organism?’

‘Well, yes. It’s very clear that Neanderthals and modern humans were really occupying the same niche. We see that unambiguously in the archaeological sites: the diet consists of the same foods – especially reindeer, horse, rhinos and mammoth.’

‘But why did we modern humans survive and not Neanderthals?’

‘Well, there’s no question the Neanderthals were very effective hunters, and really were at the top of the food chain. But we do see some differences in technology. I think that the innovations that modern humans developed in Europe, the Upper Palaeolithic toolkit, organic artefacts, but also figurative art, ornaments and musical instruments – these are all things that seemed to help give them an edge against the Neanderthals.’

I found it hard to imagine why art and music might have given modern humans an advantage.

‘Well, think of the lion-man,’ said Nick. ‘There’s a lion-man from this valley, and a lion-man from the Auch Valley. It’s the same iconography, the same system of beliefs, the same mythical structure, and they’re the same people. And we don’t see those kinds of symbolic artefacts with Neanderthals, so it seems that their social networks were much smaller than those of modern humans.

‘And from my point of view,’ he continued, ‘the evidence even at this time, 35,000 years ago, is completely unambiguous: music was a really key part of human life. It’s not entirely clear how that would give you a major biological advantage over the Neanderthals, but it seems to fit into this complex of symbolic representation, larger social networks. Perhaps music helped to form the glue that held these people together.

‘When the competitor arrived, the Neanderthal way of doing things wasn’t as effective in the face of people who had new ways of doing things, new technology, new culture and social networks,’ explained Nick.

Whereas competition for an ecological niche seemed to have spurred modern humans on to develop wider social networks, the Neanderthals appeared to be ‘culturally locked in’. It was a competition that modern humans would eventually win. Nick explained that, while their respective territories probably shifted back and forth over the centuries and millennia, Neanderthals were, on average, retreating while modern humans expanded.

‘In regions like the Levant, we have good evidence for movement back and forth of the two populations. It’s certainly not the case that modern humans always immediately expanded at the cost of Neanderthals; there are some good examples of Neanderthals displacing early modern humans, too.

‘When the new people came in, resources got tight, and modern humans were able to develop new technologies and new solutions quicker than the Neanderthals. In a sense there was a continual cultural arms race going on. And here, in this setting, it seems like a lot of innovations took place that gave the modern humans a bit of an edge. But it wasn’t a sudden, blanket devastation of the Neanderthals: there was a lot of give and take, but, ultimately, they were pinched out demographically.’

‘So do you think modern humans and Neanderthals were actually in contact with each other?’ I asked.

‘Well, in some areas, there were fairly dense populations of Neanderthals. And I think they did meet. And I think they would have been checking each other out from a distance, often avoiding each other. That was probably the most common scenario, but there may have been times when they came together, in peaceful co-existence, and times when there was quite a bit of conflict.’

‘What do you think about the question of interbreeding?’

‘Any place where people come together, interbreeding is the most normal thing in the world. So I think there were occasionally encounters where interbreeding took place, but not very often, and so it didn’t contribute very much to our genetic make-up or our anatomy.’

While it’s difficult – even impossible – to summarise the interactions that may have occurred between the two populations over so many thousands of years, the question ‘Why did we survive to the present while Neanderthals disappeared?’ is still relevant. Even if members of the two species never came face to face, they were in competition with each other in the landscape. And there was archaeological evidence for different subsistence strategies, which, for modern humans, included different and possibly more flexible technology, as well as culture and complex social networks, which may ultimately explain why we are here today and the Neanderthals aren’t.

Later that day, Nick took me to Vogelherd itself, in the lush Lone Valley, where excavations were ongoing. A team of archaeological technicians and students were busy digging down through the spoilheap (or ‘backdirt’) of the original excavation, finding plenty of evidence that had been discarded by the first archaeologists who dug there.

‘The site was first dug in 1931, and all of the material was dumped outside the cave,’ explained Nick as we walked past the cave entrance. ‘We’re systematically digging through it all to find out what they missed.’

It looked like a very pleasant place to be digging. The cave was set on a hill above an idyllic, lush, green valley. I asked Nick what it would have been like 35,000 years ago.

‘If you’re talking about the Ice Age, you think of ice: white, stark, and inhospitable. That’s wrong. I mean, it was cold in the winter, but in the spring and summer it would be more like it is today: lots of grass, greenery, really abundant fodder for the animals. Just think about a mammoth: the archetypal animal of the Ice Age. A mammoth eats about one 150 kilos of grass every day to stay alive. The mammoth steppe was a very rich environment, and at these sites in the Lone Valley we see abundant remains of woolly rhino, mammoth, reindeer, horses, all kinds of animals.’

‘But it must have been very cold during the winter here?’ I suggested.

‘Well, yes. But humans – and Neanderthals – can live almost anywhere as long as there’s something to eat, and materials, particularly hides, to make clothing out of, and controlled use of fire.’

Nick wandered around the site, visiting trenches to see what finds had emerged that day. These included fragments of flint blades, quite typical of Aurignacian toolkits. The sediment was being bagged up as it was removed, and would be sieved. It was only through this careful sifting of the soil that Nick’s team had found the fragments of ivory that made up the ivory flute, and the head of the bird carving.

But Vogelherd had contained disappointments as well as revelations. On first excavating it in 1931, archaeologists dug out some 300m3 of sediment from inside the cave, finding Middle and Upper Palaeolithic artefacts in distinct layers. The latter included a rich collection of Aurignacian tools and artefacts, which have since been radiocarbon dated to 30,000 to 36,000 years ago. The archaeologists also found modern human remains including two crania and a mandible, embedded in the Aurignacian layer. These bones, in association with the Aurignacian tools, seemed to provide conclusive evidence that modern humans were the makers of this technology. The findings from Vogelherd tallied with the discoveries at the Cro-Magnon rockshelter in France, where modern human skeletal remains – ‘Cro-Magnon Man’ – had been found associated with Aurignacian tools.2 This link between modern humans and a particular technology meant that archaeologists could assume the presence of modern humans, in the absence of skeletal remains, when they found Aurignacian tools and artefacts. At other sites, Neanderthal remains had been found associated with Mousterian (Middle Palaeolithic) tools. So it seemed that each of these populations had a clear ‘signature’ that archaeologists could use to map out their sites and territories in Europe.

In 2004, Nick Conard and his colleagues published radiocarbon dates for the skeletal remains from Vogelherd: they dated to a mere 4000 to 5000 years ago. It looked as if they were intrusions from late Neolithic burials near the cave entrance. The ‘association’ with the Aurignacian layers in the cave was incidental. This disappointing result had wide implications. Vogelherd had been a key site for demonstrating that modern humans made the Aurignacian. And in 2002, radiocarbon dates had been published for the Cro-Magnon skeletal remains as well, showing them to be about 28,000 years old: too young for the Aurignacian tools in the rockshelter, although nowhere near as young as the Vogelherd bones had turned out to be.2 The identification of modern human sites through Aurignacian tools alone was starting to look decidedly shaky.