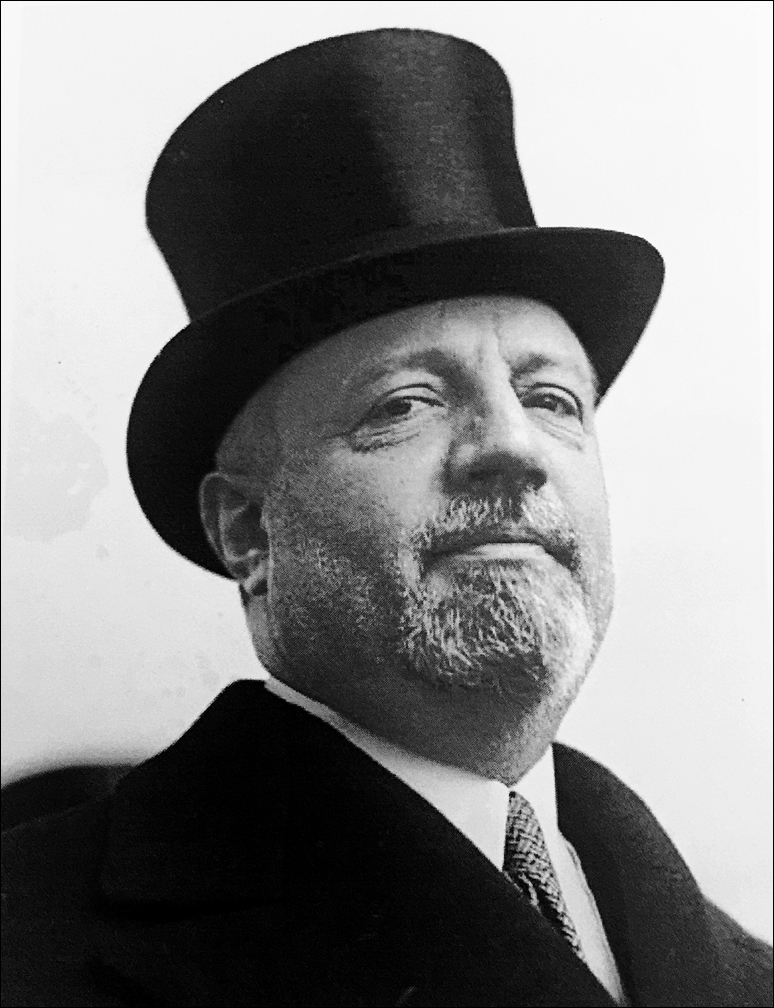

1. and 2. From the sixth century, much of the money to run the Catholic Church’s lavish Papal Court came from the sale of indulgences, promises that God would forgo earthly punishment for the buyer’s sins. By Gregory XVI’s papacy (1831–1846), overspending, abysmal management, and antiquated views about investments forced the Pope (left)—to borrow money from James de Rothschild (right), the patriarch of Europe’s preeminent Jewish banking dynasty.

(3) For more than a thousand years, along with leading the church, Popes were monarchs of the Papal States, a temporal kingdom that at its height in the late eighteenth century included much of central Italy. A succession of Popes condemned the popular uprisings that toppled European monarchies as a destabilizing modernist movement. Here, two Italian nationalists are beheaded in Rome in 1868.

(4) As the rebellion to unify Italy gained momentum, the Vatican paid for its own army—Zuavi Pontifici (Papal Infantry)—of mostly young, unmarried Catholic volunteers from many countries. However, when in 1870, nationalist troops massed outside Rome, Pius IX (1846–1878) realized his militia was outnumbered, and ordered the white flag raised over St. Peter’s Basilica. That surrender reduced the church’s 16,000-square-mile empire to a tiny parcel of land.

(5) For Pius IX, the loss of the Papal States—the church’s earthly symbol of power—also deprived it of huge income. Pius, the first Pope to be photographed, declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican and steadfastly refused to recognize the new Italian state.

(6) Pius X (1903–1914), the first modern Pope from a working-class family, was an ultraconservative who encouraged anonymous denunciations of so-called freethinkers and modernists. And while he condemned unrestrained capitalism and reinforced the church’s backward view of finances, he also spent liberally, doubling the size of Vatican City.

(7) Bologna’s Cardinal Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa became Pope on Pius’s death in 1914. He took the Pontifical name Benedict XV (1914–1922). All countries rejected his efforts at peacemaking during World War I. By the time he died in 1922, the Vatican was reeling from a 40 percent loss of its capital caused by a series of bad investments.

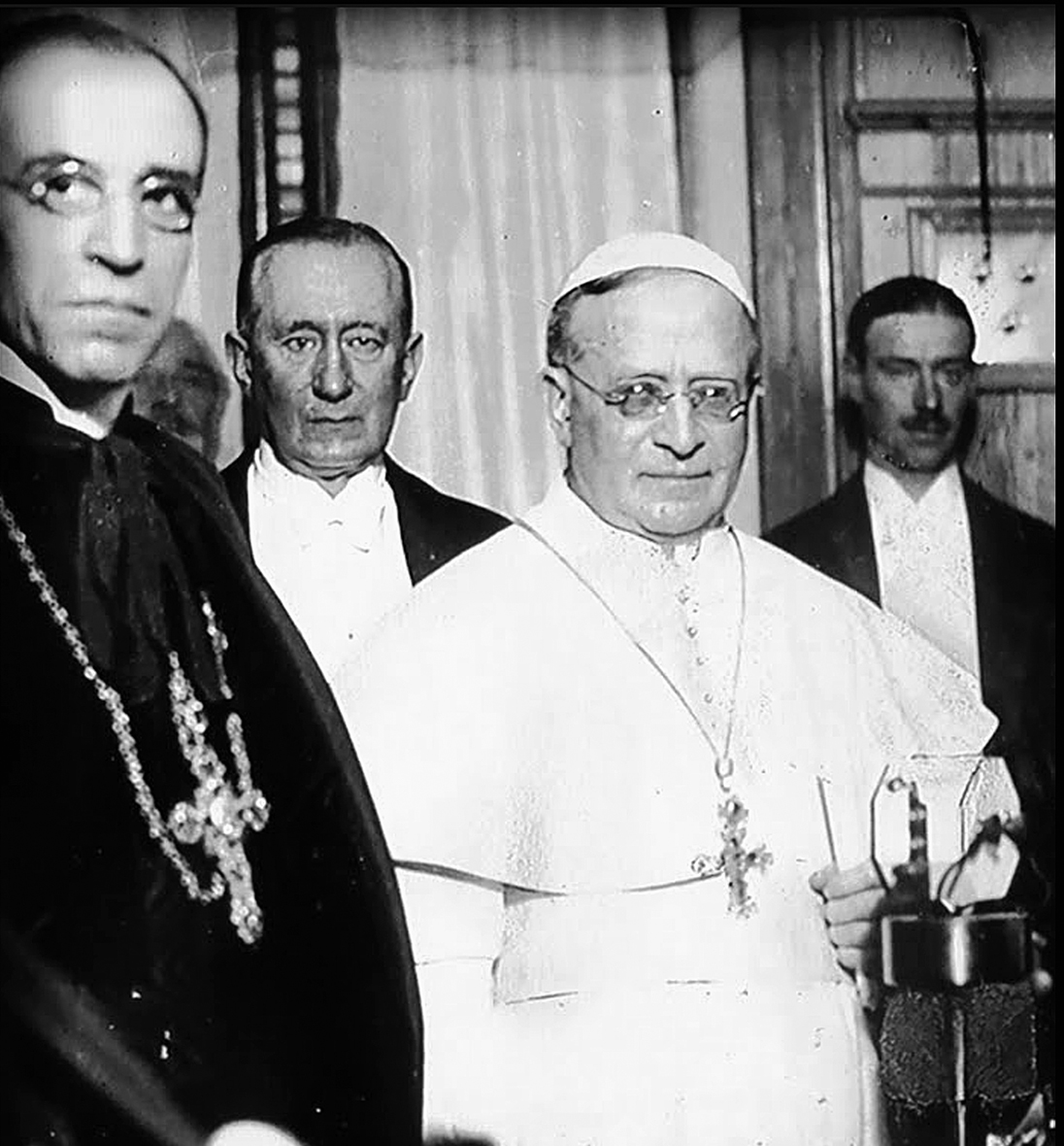

(8) The son of a Milanese factory worker, the hot-tempered Pius XI (1922–1939) ordered the Vatican’s first internal audit. It took six years to complete and revealed that the church was down to its last dollars. Yet the Pope still refused to loosen the restrictions on commercial investments or to modernize its finances.

(9) Benito Mussolini (center) led the radical right-wing National Fascist Party. Only eight months after Pius’s election, Mussolini led tens of thousands of fascists in a “March on Rome.” A week later he was sworn in as prime minister. His ascent seemed ominous for the church. An avowed atheist, he had once described priests “as black microbes who are as deadly to mankind as tuberculosis germs.”

(10) Pius feared godless bolshevism more than Italy’s fascists. Eugenio Pacelli, the Papal Nuncio to Germany, reinforced the Pope’s fear. Pacelli, who descended from Catholic aristocrats, had faced off against an armed gang of communist revolutionaries in Munich in 1925. Although he escaped unhurt, the confrontation reaffirmed his belief that communism was the greatest threat to the church.

(11) In 1929, Pius XI was the first Pope since the 1870 loss of the Papal States to recognize the Italian state. The Februrary 24, 1929, cover of La Domenica del Corriere shows Benito Mussolini (far right ) signing the treaty with Papal Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Gasparri. It recognized the Vatican as a sovereign nation and gave the church its greatest power in centuries.

(12) As part of the 1929 pact, Italy paid the Vatican for confiscating the Papal States. The Pope hired Bernardino Nogara (left), a well-connected businessman and banker, to invest the windfall. Giuseppe Volpi (right), a business tycoon, was Nogara’s close friend and mentor.

(13) Despite Wall Street’s 1929 stock market crash, Pius XI embarked on the “Imperial Papacy,” Vatican City’s largest modern-day construction boom. He approved a telegraph office, train station, power plant, an industrial quarter, and a printing facility. Here, Cardinal Pacelli (left) and Pius XI attend the opening of Vatican Radio in 1931.

(14) Secretary of State Cardinal Pacelli (seated, center), signing an agreement with German Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen (far left). In a historic 1933 accord, the Vatican was the first sovereign state to sign a bilateral treaty with Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. The Nazis promised to protect Catholics inside Germany in return for the church endorsing Hitler’s government.

(15) In October 1935, 100,000 Italian troops invaded Ethiopia, part of Mussolini’s vision for a vast East African empire. The Vatican had investments in manufacturers of wartime munitions and weapons. At left, a priest celebrates mass on the front line. Mussolini was so pleased that he told Nazi officials, “Why they [Vatican officials] even declared the Abyssinian war a Holy War!”

(16) By 1938, Pius XI picked an American Jesuit, John LaFarge, to lead a small team in drafting a Papal Encyclical—Humani Generis Unitas (The Unity of the Human Race)—condemning anti-Semitism and racism. Pius died the following year before the decree was finished. His successor, Pius XII, buried the encyclical in the Vatican’s Secret Archives. LaFarge is far right, during a 1963 presentation of the St. Francis Peace Medal to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

(17) Cardinal Pacelli, who became Pope in March 1939, took the name Pius XII. He was an acknowledged Teutonophile. In 1931, the number two Nazi, Field Marshall Hermann Göring—who had instituted so-called morality trials intended to embarrass Catholic priests and nuns—visited the Vatican. Here, Göring (second from left) is with Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, the Papal Nuncio to Bulgaria, and later Pope John XXIII. Göring sent a wire to Hitler: “Mission accomplished. Pope unfrocked. Tiara and pontifical vestments are a perfect fit.”

(18) Three days after Pacelli became Pope, Germany invaded Czechoslovakia. High-ranking Nazis and church officials met frequently despite the aggression. At a Berlin reception, Papal Nuncio Cesare Orsenigo (left) greets Hitler and his foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. In 1942, Orsenigo turned away an SS officer who wanted to confess a firsthand account of the massacre of Jews.

(19) The war presented the church with great business risks and opportunities. A central figure was Giuseppe Volpi, a former finance minister for Mussolini, and one of Italy’s most successful businessmen. With Volpi often acting as a proxy, the Vatican invested money in profitable ventures, many of which were in the killing fields of Eastern Europe.

(20) SS-Brigadeführer Walther Schellenberg directed Nazi foreign intelligence operations from July 1944. After the war he told U.S. interrogators that the Nazis “had many men in the Vatican.” Another German intelligence officer, Reinhard Karl Wilhelm Reme, disclosed the network of Third Reich agents he had recruited in Italy. That list included the name Nogara. That revelation, reported in this book for the first time, raises the question of whether the Vatican’s chief moneyman was a Nazi wartime spy.

(21) A Croatian priest based in Rome, Krunoslav Draganović, was a member of the Ustaša, an anti-Semitic, anti-Serb, and anti-communist party in power in wartime Croatia. Draganović ran one of several postwar escape networks—sanctioned by high-ranking Vatican clerics and ultimately U.S. and British intelligence—through which hundreds of criminals found safe haven in South America and the Middle East.

(22) The Vatican used gold as its chief hard asset. Since the Nazis looted the gold reserves of the countries they conquered, the church’s accumulation of the metal proved as morally problematic as did many of its business stakes. Here, an American soldier holds wedding rings from Holocaust victims. The Vatican later denied that it was the repository for the rings and gold coins from 28,000 gypsies murdered in Croatia.

(23) New York’s Cardinal Francis Spellman had been a friend of Pius XII since the 1920s, when the Pope was a Nuncio to Germany and Spellman was an ambitious monsignor. Spellman was a great asset as the Vatican’s chief American fundraiser. He was also a vehement anticommunist who ensured that the church and the CIA worked together to elect a conservative government in Italy’s first postwar election (1948). In October 1960, a month before they faced off in a presidential election, Spellman hosted Senator John Kennedy and Vice President Richard Nixon at New York’s Alfred E. Smith memorial dinner.

(24) The death of Pius XII in 1958 was a watershed moment for the Vatican. French Cardinal Eugène Tisserant (center) is blessing the Pope’s corpse. For more than nineteen years Pius had wielded the power of the Papacy as a divine monarch, a throwback to the boldest Popes from early centuries.

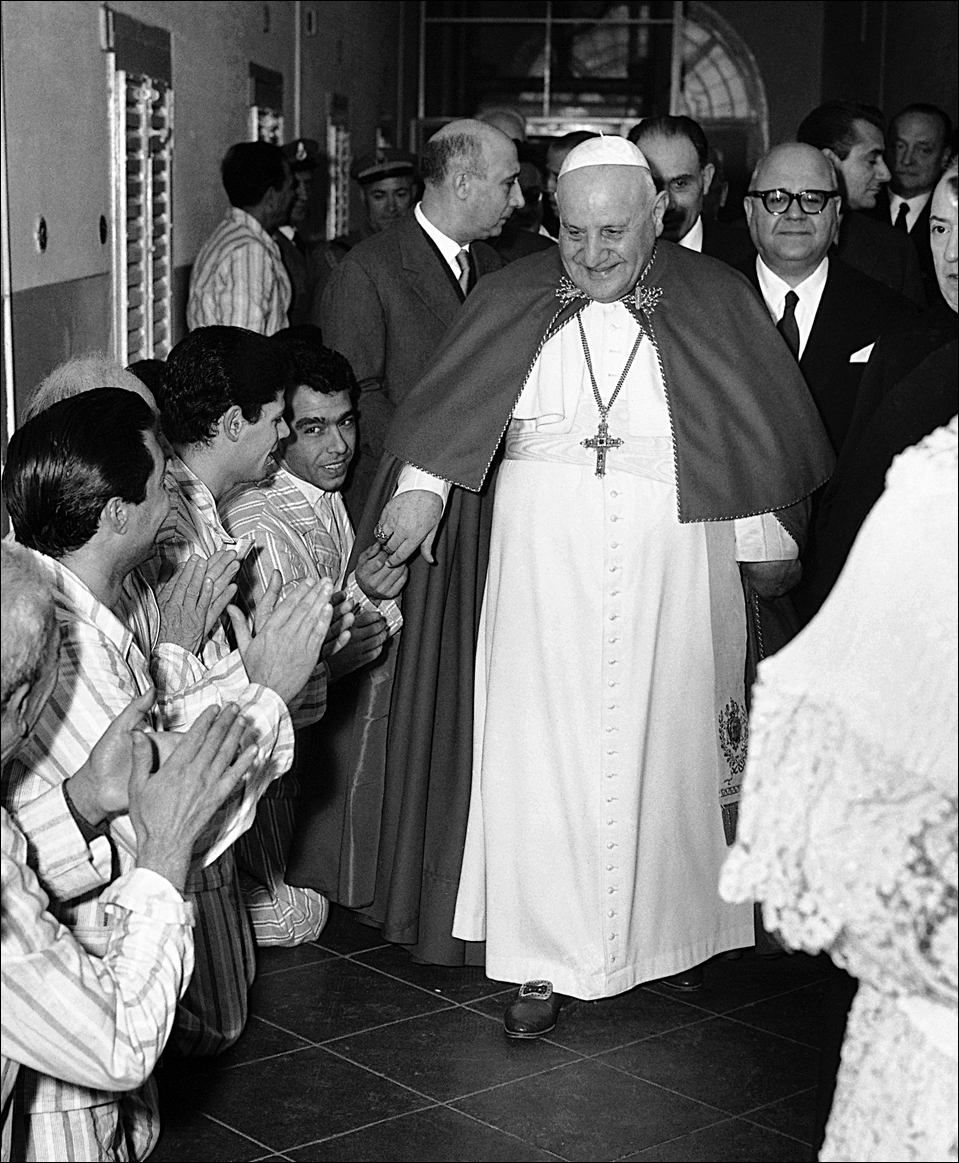

(25) It took three days and eleven ballots in 1958 before the divided cardinals settled on a compromise, Venetian Patriarch Angelo Roncalli. One month shy of his seventy-seventh birthday, he was the first Pope over seventy in more than two hundred years. His choice of John as his Papal name was a surprise: no Pope had taken it for five hundred years because the last John was a divisive anti-Pope. Although some colleagues questioned his capability, he proved wildly popular with ordinary Catholics. During his five years as Pope, John XXIII stripped away much of the pomp his predecessors had carefully guarded. In 1958 he visited Rome’s largest prison at Christmas.

(26) Paul VI (1963–1978) oversaw a revolution in how the church managed its money and investments. He relied on so-called men of confidence, lay Catholic financiers who not only advised the Pontiff about how to invest the church’s money, but also became partners with the Vatican on many speculative ventures. American Monsignor Paul Marcinkus (left) coordinated the logistics and security for the Pontiff’s foreign trips, and served as translator for U.S. dignitaries. In this 1964 audience, the Pope met with civil rights leaders Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy.

27. and 28. In the late 1950s, Michele Sindona (left), an aggressive tax attorney in Milan, started doing some legal work for the Vatican Bank. His influence grew exponentially but ended in 1974 with the then record $2 billion failure of his Franklin National Bank. For the next twelve years he battled criminal charges in Italy and the United States. In 1986, Sindona was convicted in the assassination of Giorgio Ambrosoli (right), the court-appointed liquidator of his banking empire. Two days later Sindona died in his high-security Italian jail cell after drinking cyanide-laced espresso. The coroner ruled it suicide.

(29) Many people who met the six-foot-three Chicago-area native Paul Marcinkus thought he seemed more likely to be a football lineman than a Catholic priest. His rise in the church started in 1971, when Pope Paul VI promoted him to bishop and appointed him as the chief cleric at the Vatican Bank. Marcinkus had a healthy appetite for risk, one that eventually put the Vatican Bank at the center of half a dozen international criminal and government investigations.

(30) Roberto Calvi was an ambitious banker who replaced Sindona as the leading Italian financier working with the Vatican Bank. When his overextended empire collapsed, it almost took the Vatican Bank with it. In 1982, while on the run from Italian police, Calvi turned up dead, hanging from Blackfriars Bridge in London. Ruled at first a suicide, it took the Calvi family twenty-five years to convince authorities that he was murdered. In 2010, five men were tried and acquitted in Italy. Calvi’s murder remains unsolved.

31. and 32. Luigi Mennini (left ), the father of fourteen children, was a savvy private banker who started working in a Vatican financial department in 1930. Massimo Spada (above, center left ) was a stockbroker who began working there in 1929. Over several decades they became the most powerful lay executives at the Vatican Bank and were key advisors to Marcinkus. Italian prosecutors unsuccessfully tried bringing both men to trial—with Marcinkus—for fraud.

(33) Licio Gelli was a wealthy businessman with a reputation as a fixer. He also led a secret, underground Masonic lodge, Propagande Due (P2). By the time police disbanded it in 1981 over suspicions it was plotting a coup, its 953 members were such a stunning collection of “who’s who” that Italian journalists dubbed P2 a “parallel state within a state.” Sindona and Calvi were members, and Gelli did business with Marcinkus and the Vatican Bank.

(34) Albino Luciani, the Patriarch of Venice, was elected Pope in 1978. He took the Papal name John Paul I. Three days later a nun found the sixty-five-year-old John Paul dead in his bed. The cardinals voted not to conduct an autopsy (at left, his body on display). Unfounded but popular conspiracy theories that the Pope was murdered to prevent him from reforming the Vatican Bank have since flourished.

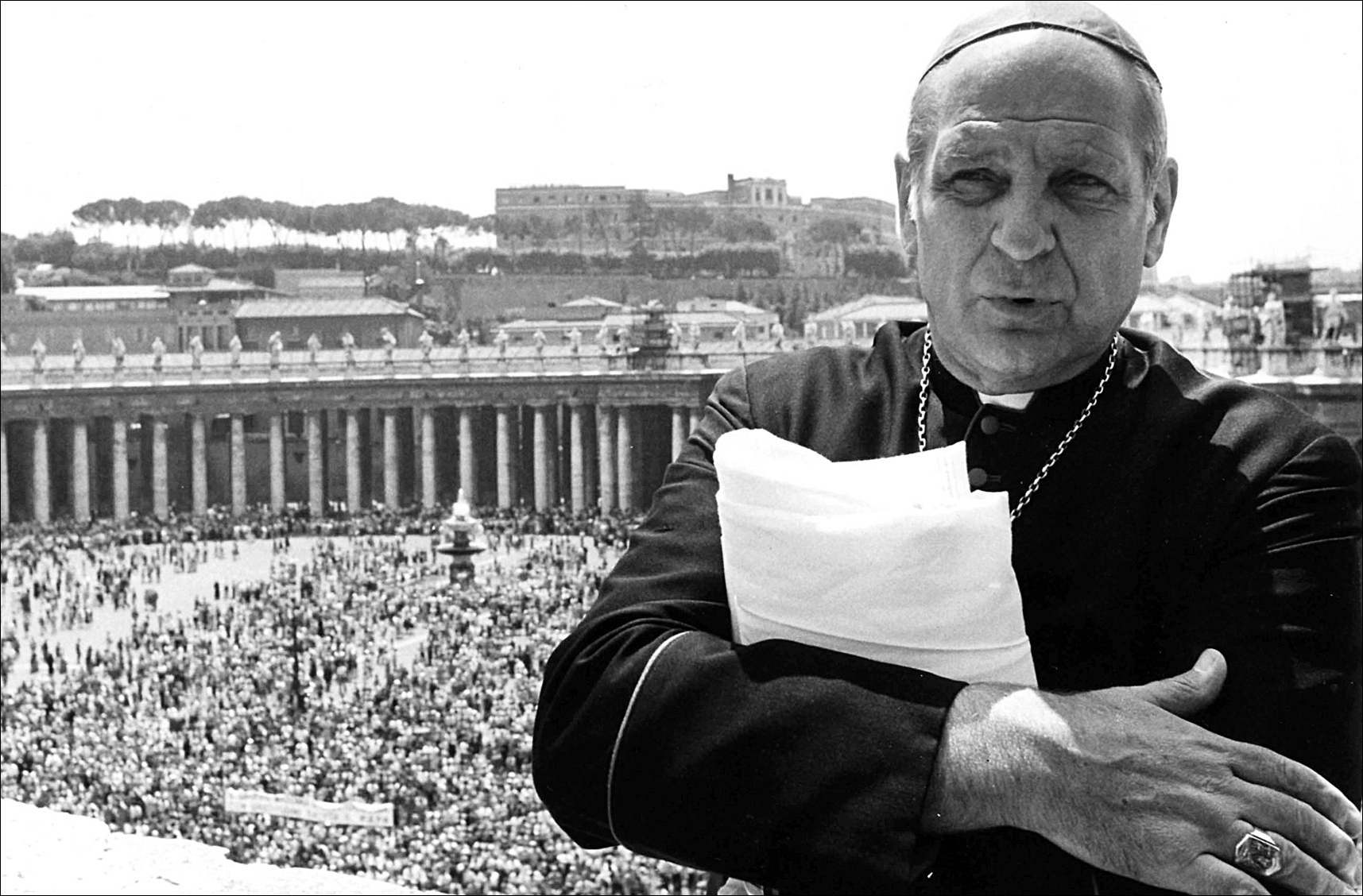

(35) It took three days for the cardinals to select Kraków’s Karol Jósef Wojtyla. At fifty-eight, he was the youngest Pope since 1846 and the first non-Italian selected in more than four centuries. He took the name John Paul II. His fierce anticommunism made him a natural ally of Ronald Reagan, shown here with Nancy Reagan meeting John Paul for the first time in 1982.

(36) CIA director William Casey met with John Paul II frequently, and the Vatican and the United States shared intelligence about the Eastern Bloc. With the Pope’s approval, millions of dollars of covert U.S. aid passed through the Vatican Bank to Solidarity, the Polish trade union at the heart of resistance to the Communist government. On May 13, 1981, at St. Peter’s Square (right), a Turkish gunman shot and almost killed John Paul. To this day, many believe that the anticommunist Pope was the target of a plot hatched by Bulgarian intelligence.

(37) In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed an executive order declassifying wartime files from eleven key government agencies, including the CIA, NSA, and State Department. One 1946 memo from a Treasury agent reported that about $225 million in stolen gold had ended up at the Vatican. Edgar Bronfman Sr., the influential head of the World Jewish Congress (right), spearheaded an international restitution effort that relied in part on lawsuits from survivors, as well as pressure from Western governments. Only the Vatican refused to open its files or make any contribution to a Holocaust compensation fund.

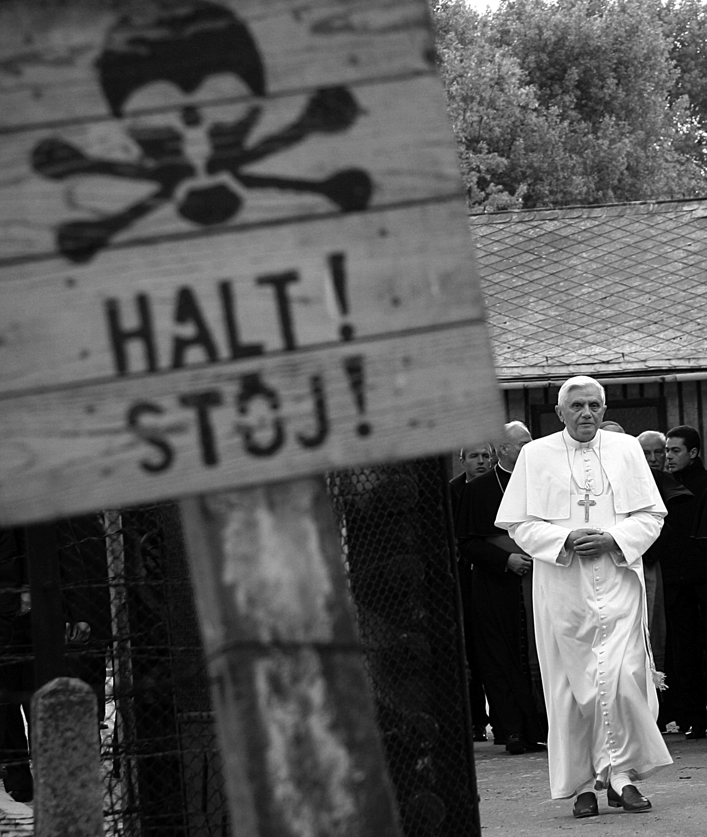

(38) In 2006 John Paul visited the Nazi death camp Auschwitz.

(39) The last decade of John Paul’s Papacy was defined in part by his personal battle with Parkinson’s disease. Upon his 2005 death, many Vatican observers expected the cardinals to select a younger Pontiff. But their choice was seventy-eight-year-old Cardinal Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger. A hardline conservative, Ratzinger was the first German elected Pope in a thousand years. His Papal name was Benedict XVI. His selection sparked controversy in part because he had served as a teen in the Hitler Youth (at sixteen, in 1943, drafted into a German antiaircraft unit).

(40) Benedict selected Genoa’s Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone (center) in June 2005 as his Secretary of State. Bertone stocked the Vatican’s bureaucracy with loyalists and resisted financial reforms. Benedict’s unprecedented resignation in 2013 stunned insiders and ordinary Catholics alike. On the far left is German Monsignor Georg Gänswein, Benedict’s personal secretary.

(41) When Gänswein appeared on the cover of the Italian edition of Vanity Fair in 2013, it kicked off a firestorm of backbiting and jealousy about him inside the Vatican.

(42) In 2009, Benedict appointed Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, a conservative economist and chief of Italian operations for Spain’s Banco Santander, as the president of the Vatican Bank. The outspoken Gotti Tedeschi irritated many senior clerics. What little headway he made in reforming the Vatican Bank was stopped cold by a 2012 Italian criminal investigation into money laundering. Gotti Tedeschi was dismissed after a “no confidence” vote by the Vatican Bank’s directors.

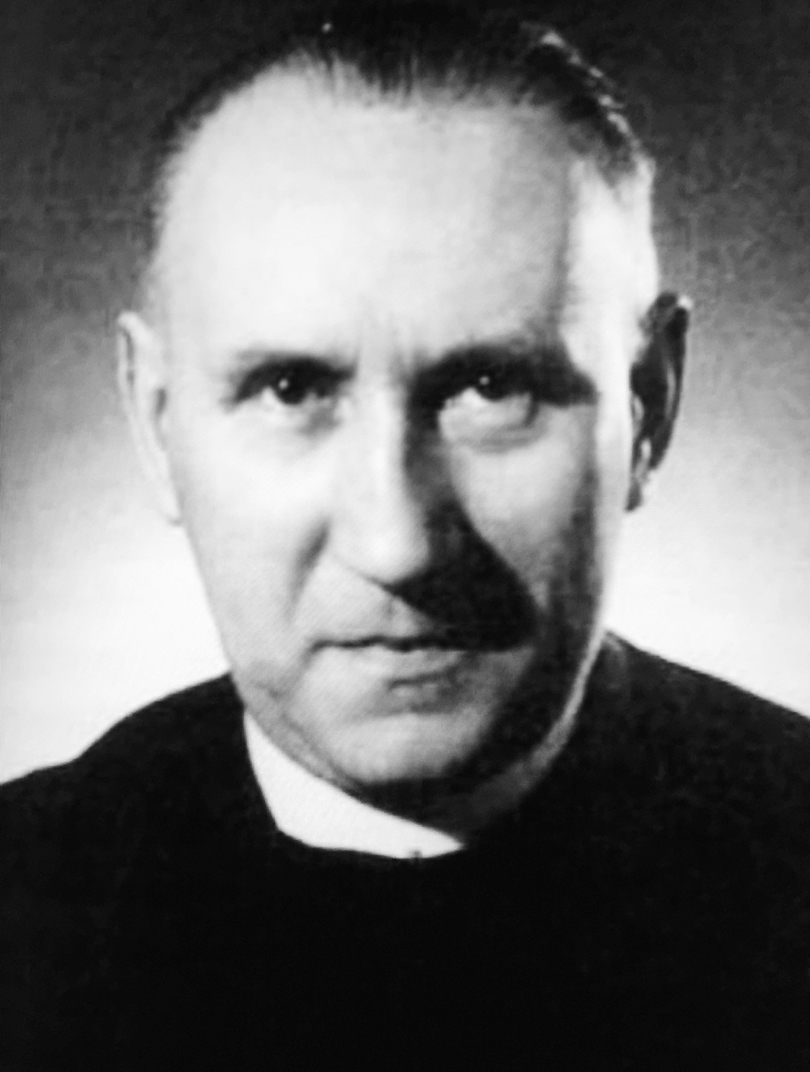

(43) At the conclave of cardinals in March 2013 that selected Benedict’s replacement, most church observers wrote off Buenos Aires’ Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio (above, in 1966, as a seminarian). Although he had finished second in the 2005 vote, at seventy-six he was thought too old. But it took only five votes to put him over the top. Pope Francis emerged from the conclave as a likable and humble populist who was instantly popular with both Catholics and non-Catholics.

(44) Pope Francis as “Man of the Year” for 2013 on the cover of Time magazine.

(45) Pope Francis has backed the reformers when it comes to the finances of the Vatican. One of the key arrivals is René Brülhart. He is a forty-two-year-old Swiss anti-money-laundering expert who for eight years ran Liechtenstein’s Financial Intelligence Unit. At the Vatican, he has earned the full support of Pope Francis. When Brülhart complained that five directors on his regulatory authority were slowing his progress, Francis fired them all in May 2014. Two months later the Pope hired a trio from Wall Street to fix the Vatican’s wayward finances.