The story of how Singapore got its name reads rather like a fairy tale. The earliest (and most racy) of Malay histories, the 17th-century Sejarah Melayu, tells of the exploits of Sang Nila Utama, who assumed the title of Sri Tri Buana as ruler of Palembang, heart of the great Malay seafaring empire of Srivijaya. He was out searching for a place to establish a city one day when his ship was struck by a sudden and ferocious storm. The ruler reputedly saved the day by casting his crown into the waves. Ashore on an uncharted island, he was intrigued by the sight of a strange creature with a red body, black head and white breast. On enquiring of its name and told it was a lion, he decided to name the place Singapura, which means “Lion City” in Sanskrit.

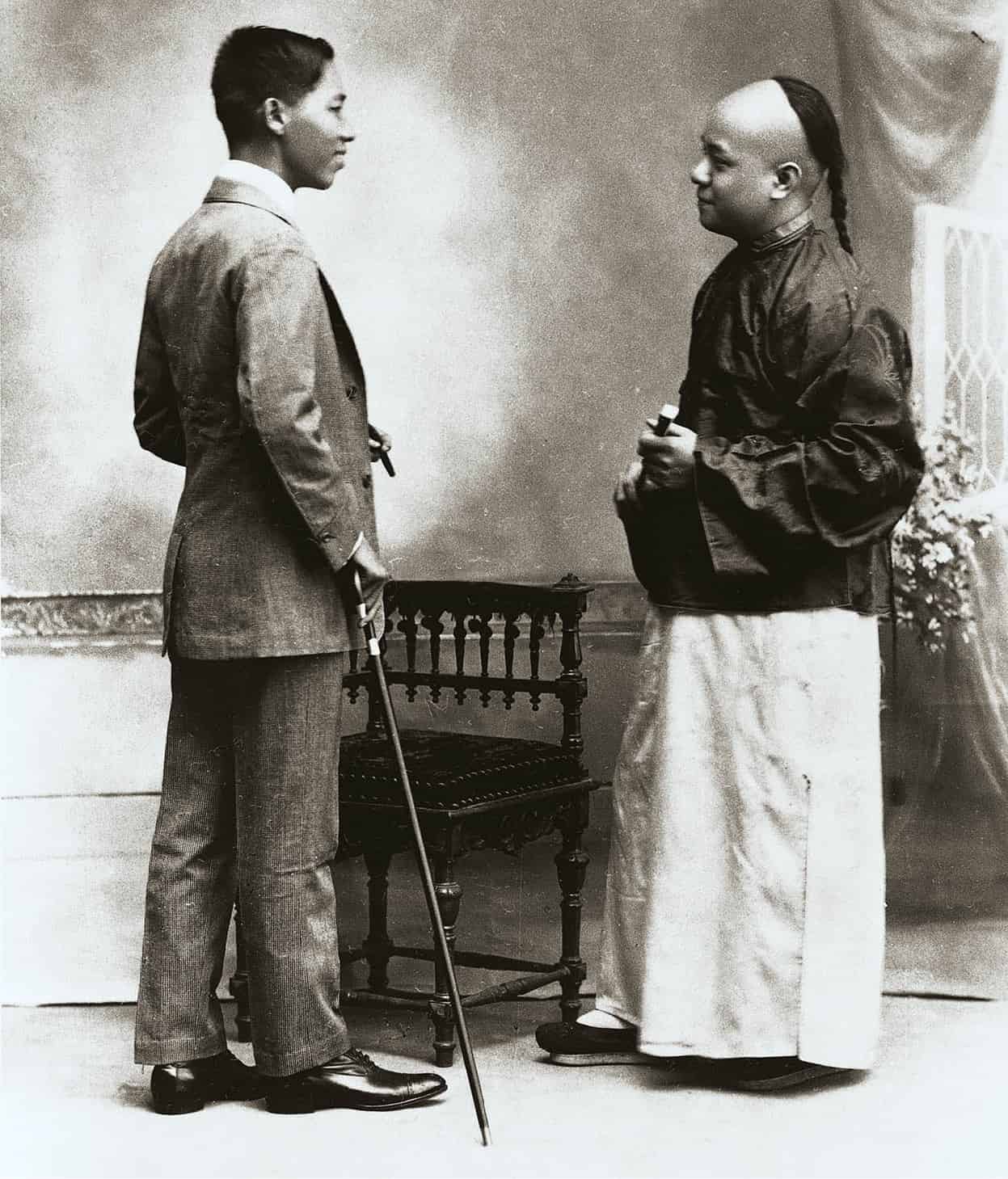

Contrasting faces of early Chinese businessmen.

National Archives of Singapore

Merchants and pirates

Singapore owes its reputation as a trading centre to the bustling activity in the region. Even before the birth of Christ, Tamil seamen from southern India were plying heavy ships through the Straits of Melaka (Malacca). Later, the Greeks and then the Romans sought tortoise shell, spices and sandalwood from the Malay archipelago. By the 5th century, Chinese junks were sailing into peninsular waters, braving “huge turtles, sea-lizards and such-like monsters of the deep”. The Arabs and Persians traded in the region too.

By the 14th century, Singapore was well established on this East–West trade route. Though its various rulers exacted duties from the passing ships, what most worried traders were the so-called “freelancers”: pirates.

Traders from all over Asia stopped at Singapore, which occupied a pivotal point on the tip of the Malay peninsula.

According to the 1350 Chinese text Description of the Barbarians of the Isles, the traders were unmolested as they sailed west. But on the way back, loaded with goods, “the junk people get out their armour and padded screens against arrow fire to protect themselves, for a certainty two or three hundred pirate junks will come out to attack them. Sometimes they have good luck and a favouring -+wind and they may not catch up with them; if not, then the crews are butchered and the merchandise made off with in short order.” The scale of the pirate fleet seems inflated, but there is no doubt the threat was real.

17th-century map of the Malay peninsula.

Private Archives

Singapura, often called “Temasek” in the literature of that period, was most likely founded around 1390 by the Palembang ruler Parameswara. A scion of the former Srivijaya empire, he had fled Palembang after an abortive attempt to cast off allegiance to the great Javanese Majapahit empire (1292–1398). His Temasek settlement was short-lived, however. Towards the end of the 14th century, it came under attack, possibly by the Majapahits but more probably by the Thai state of Ayutthya or one of its Malay vassals.

Temasek came under the authority of the newly founded Melaka sultanate, and later devolved into an insignificant fishing settlement, becoming little more than an overgrown jungle. When Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, landed here on 29 January 1819, he found swamps, jungle and a lone village of some 100 Malay huts by the mouth of the Singapore River. Upriver lived 30 or so Orang Laut sea nomad families. It was, to put it mildly, a pretty bleak picture.

The island was controlled by the Temenggong, the Malay chief of the southern Malay peninsula, and the land was owned by Johor.

The Sultan of Johor had four wives but no clear heir, though he had two sons by two different commoners. When the sultan died, the younger of the two sons was placed on the throne, with the legitimacy of his rule recognised by both the British and the Dutch. The elder son, Hussein, who was away at the time, subsequently went into exile.

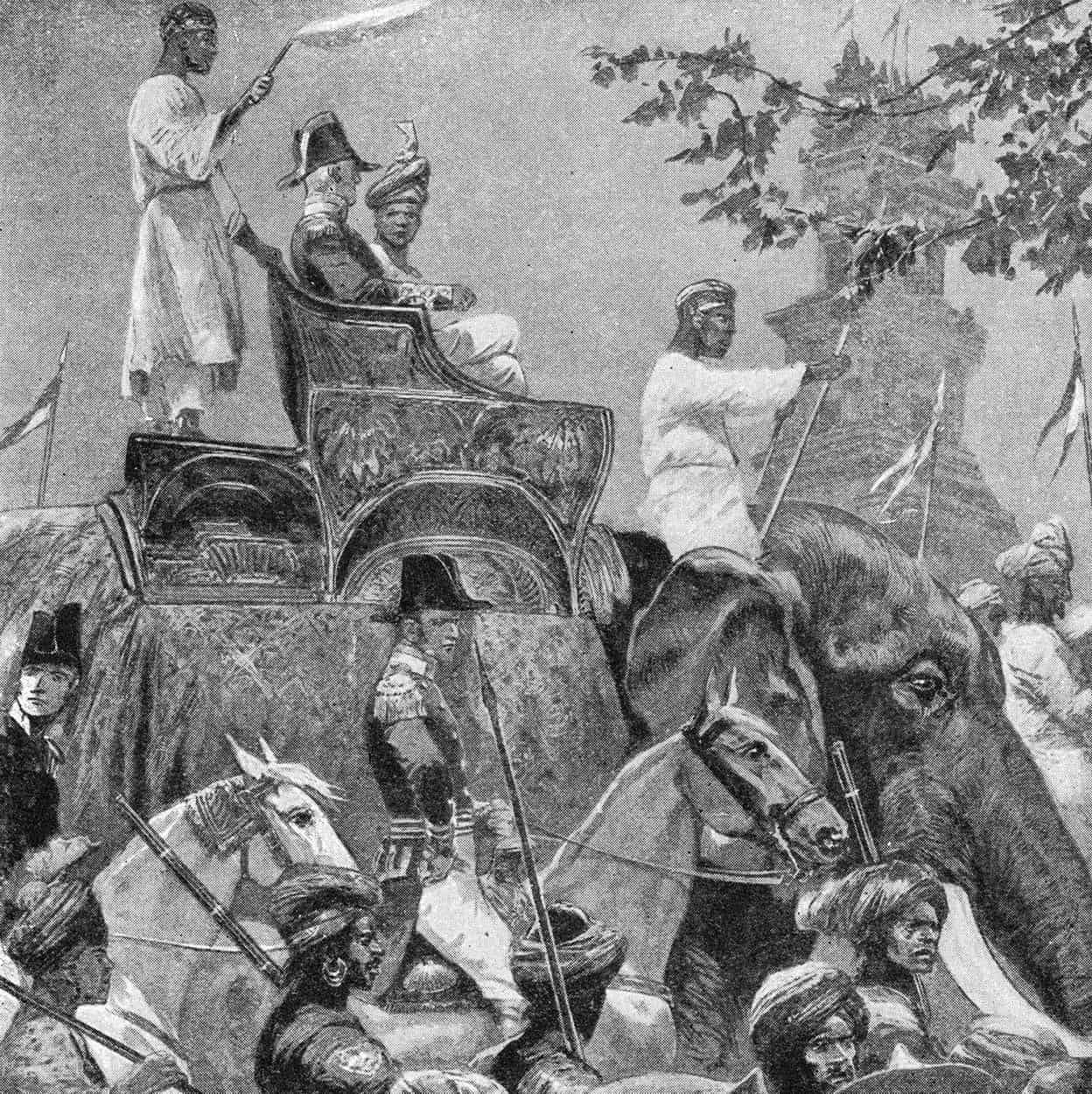

The British enter Singapore to take control in 1824.

Mary Evans

Raffles’s shrewd move

Raffles knew the younger son would never permit the establishment of a British presence in Singapore and concocted his own plan. He invited the elder son Hussein to Singapore and proclaimed him heir to the throne of Johor. On 6 February 1819, Raffles signed a treaty with the Temenggong and the new sultan, giving the British East India Company permission to establish a trading post in Singapore. In return, the company would pay the Temenggong 5,000 Spanish dollars a year and the sultan 3,000 dollars. Raffles returned to Bencoolen, leaving Major William Farquhar in charge as the island’s first Resident while retaining ultimate control as lieutenant-governor of Bencoolen.

On arrival in 1819, Raffles found “all along the beach…hundreds of human skulls, some of them old but some fresh with the hair still remaining, some with the teeth still sharp, and some without teeth.”

Farquhar cleared the jungle, constructed buildings and dealt with the rat problem. The first settlers were traders and itinerants, mostly Chinese, with others from the Middle East, Europe and Melaka. The population topped 5,000 by June 1819, from 1,000 in January.

When Raffles returned to Singapore in 1822, he drew up a detailed plan for its development. Among other things, he abolished gambling, going so far as to order that all keepers of gaming houses be flogged in public. Two years later, the British, having traded off other regions to the Dutch, took formal control of Singapore. Payments to Sultan Hussein and the Temenggong were increased in exchange for outright cessation of the island.

His health ailing, Raffles returned to England in 1823 and died three years later of a suspected brain tumour. The British put Singapore under the Indian colonial government, appointing a new Resident, John Crawfurd.

By 1824, the island was home to 11,000 people, mostly Malays, with a large number of Chinese and Bugis, and fewer Indians, Europeans, Armenians and Arabs. Under Crawfurd, Singapore began to make money for the British. He ran a tight ship and his strict adherence to the bottom line alienated many locals. He made no friends among the Europeans either when he reopened the gaming houses.

As Resident, Crawfurd had his work cut out. In the early 1830s, much of the town area was still swampland. Floods and fires were major hazards, while the filth and bad drainage, and the resulting water pollution, caused cholera outbreaks. Violent crime was another problem; gangs of robbers raided the town almost every night. Added to these were poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding and excessive opium smoking, the last of which exacted the heaviest toll. Tigers were a menace, devouring as many as 300 citizens a year during the mid-19th century. The introduction of a government bounty led to the last tiger being shot in 1904.

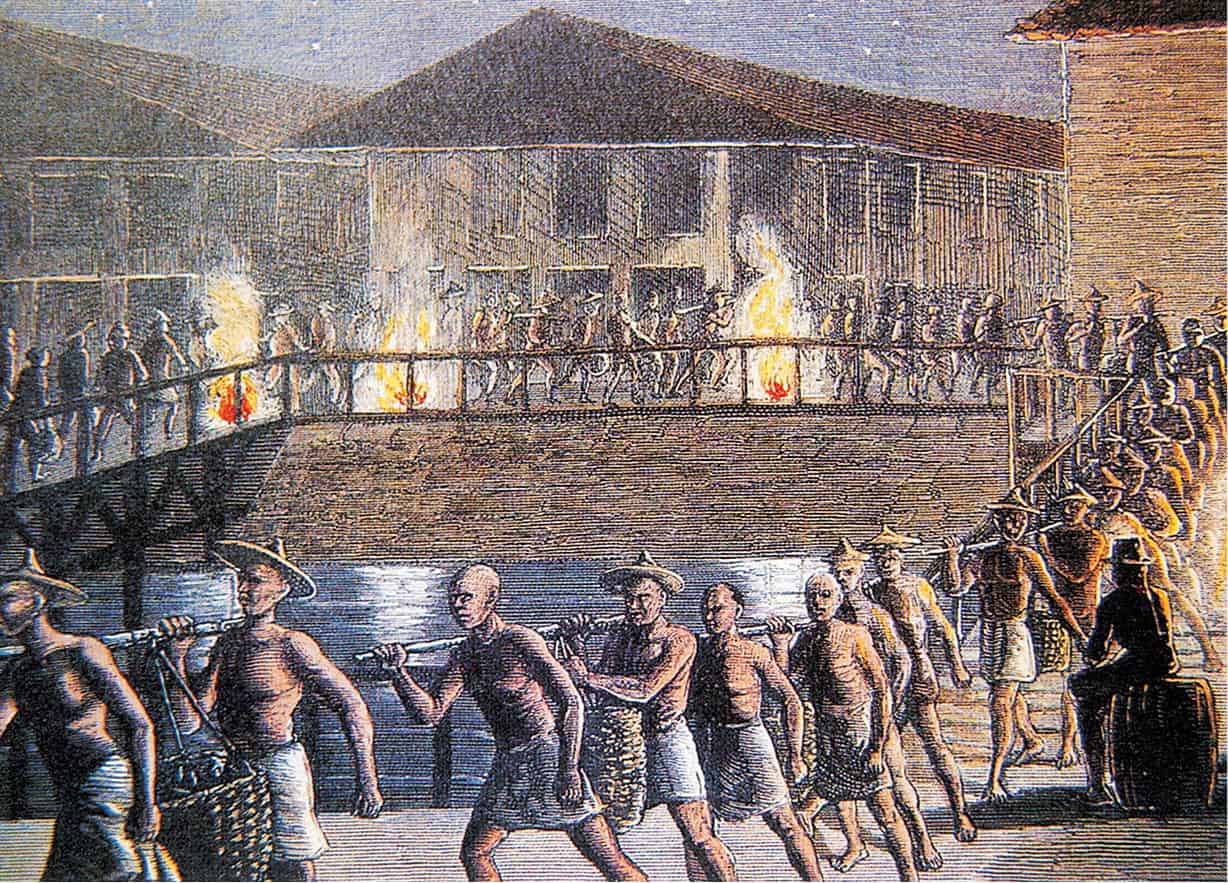

In the 19th century, most Chinese came to Singapore as indentured labourers.

Private Archives

By 1860, Singapore’s trade had reached £10 million a year. Among the goods traded were Chinese tea and silk, ebony, ivory, antimony and sage from across the archipelago, and nutmeg, pepper and rattan from Borneo. From India and Britain came cloth, opium, whisky and haberdashery for the expatriates.

By this time a sense of permanence had been established; three banks had been set up and elaborate houses of worship built. Wealthy Europeans constructed Palladian-style houses. A writer described the charming city, with its bustling harbour, lush greenery and fine houses, as “the Queen of the Further East”.

Literary greats

Singapore has been a source of inspiration for several international literary greats over the years.

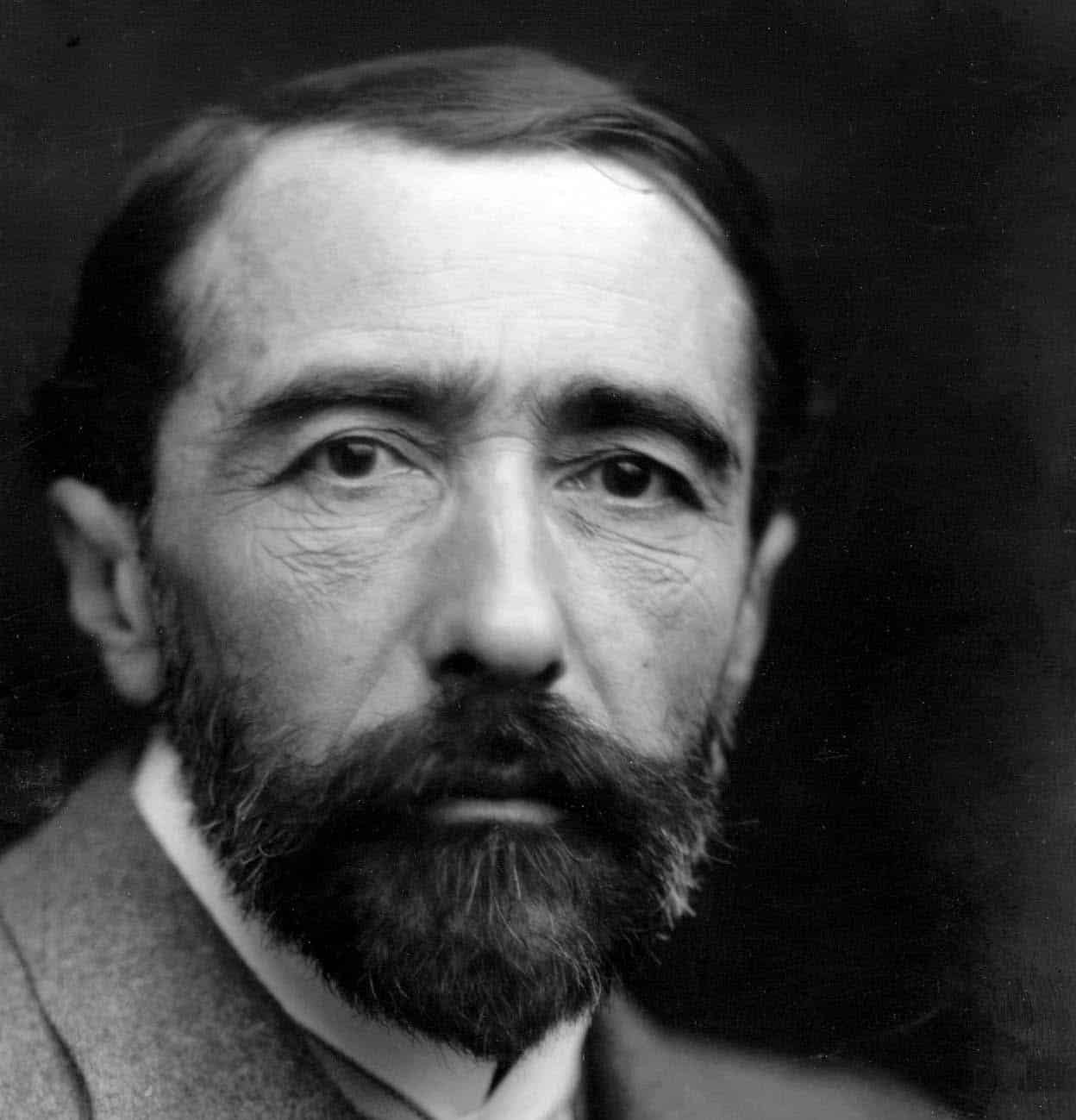

For more than 100 years, Singapore has been kind to the travelling scribe. Many stayed at the Raffles Hotel, a home away from home for the likes of Hermann Hesse and American James Michener, who has a suite named after him in the hotel. But, above all, Singapore played host to the literary lions of the British empire such as Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling and Somerset Maugham.

Joseph Conrad spent 16 years (1878–94) as a seaman in the Far East, with Singapore as his most frequent port of call. Lord Jim (1902) was inspired by a real-life incident in which a ship called the Jeddah was abandoned by her British crew when the vessel began taking on water after leaving Singapore. Conrad also drew material from his own life. He was first mate on the Vidar, a schooner circuiting between Singapore and Borneo, travelling up rivers deep inland and giving Conrad a close-up view of life in the Eastern tropics. A few of his works can be traced to these trips, including his first novel, Almayer’s Folly (1895), and Victory (1915).

Rudyard Kipling came to Singapore in 1889, when he was 24, and had just left his beloved India on his way back to England via the US – a journey that would change his life for ever. Kipling’s seven years in India were spent writing for English-language newspapers, and clever dispatches earned him a reputation as a rising star of British journalism.

Kipling was fond of strolling along the waterfront and seemed to have stumbled upon Raffles Hotel by chance, describing it as a place “where the food is as excellent as the rooms are bad. Let the traveller take note. Feed at Raffles and sleep at the Hotel de l’Europe.” The latter was demolished in 1900.

When Hermann Hesse reached Singapore in 1911, he was already well known in Germany for works such as Peter Camenzind (1904) and Gertrude (1910). Hesse observed the English, and penned acerbic descriptions of tipsy Englishmen who “fought with each other half the night like pigs”.

From his three visits to Singapore between 1921 and 1925, Somerset Maugham collected material for magazine articles that later went into his collection of short stories, The Casuarina Tree. In it, Maugham’s descriptions of Singapore’s inhabitants are perceptive: “The Malays, though natives of the soil, dwell uneasily in the towns, and are few. It is the Chinese, supple, alert, and industrious, who throng the streets; the dark-skinned Tamils walk on their silent, naked feet, as though they were but brief sojourners in a strange land… and the English in their topees and white ducks, speeding past in motor-cars or at leisure in their rickshaws, wear a nonchalant and careless air.”

Joseph Conrad.

Getty Images

Immigrant entrepreneurs

By this time, the Chinese population had swelled to 61 percent of the total and showed no signs of slowing down. Most Chinese immigrants (sinkeh) came as indentured labourers and later struck out on their own. The number of Malays also increased, though less rapidly. Immigrants from South India came as well, some as merchants and labourers, others as convicts brought in by the British to build roads, buildings and other public works.

In these early days, Chinese men outnumbered the women 15 to 1, and the social lives of young bachelors revolved around secret societies. These societies used coercive tactics to run criminal rackets and secure territory. To control the situation, in 1877 the government installed a Chinese protectorate headed by W. A. Pickering, the first European who could read and speak Chinese.

View of the waterfront in front of Fort Canning at the turn of the 19th century.

Bridgeman Art Library

In 1867, the Straits Settlements were made a Crown Colony under London’s direct control, and a governor was appointed. In its early days, as sailing ships gave way to steam vessels, Singapore became a coal station for ships travelling to Europe through the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869. Singapore’s trade expanded eightfold between 1873 and 1913 as a result, securing its permanent status as a major entrepôt on the leading East–West trade route, and a most vital commercial link in the chain of the British empire. By 1903, the little island had become the world’s seventh-largest port in terms of shipping tonnage.

In 1911, the population stood at 312,000 and included 48 races speaking 54 languages, according to census-takers. During this period, a large number of Europeans migrated here, marking perhaps the nadir of colonial snobbery. They distanced themselves from the “locals”, eating Western food shipped in at great cost, and barring other races from their social clubs and prestigious civil service posts. Roland Braddell’s The Lights of Singapore (1934) described life as “so very George the Fifth… if you are English, you get an impression of a kind of tropical cross between Manchester and Liverpool.” With the building of its airport a few years later, Singapore was headed towards modernisation. Then came World War II.

Britain, a firm Japanese ally during World War I, severed her treaty with Japan in 1921 at the suggestion of the US. As war tensions in the Pacific increased, Singapore was groomed as a regional base for British warships in the event of an outbreak of hostilities. In 1927, Japan invaded China, occupying Manchuria by 1931 and withdrawing from the League of Nations. Six years later, the Japanese formally declared war on China. Airfields and dry-dock facilities for the British fleet were completed in Singapore in 1938. The substantial-looking defences earned the island the moniker “the Gibraltar of the East”.

Japanese prison camps were tropical hell-holes of rats, disease and malnutrition. Many of the prisoners sent to work camps in the jungles of Southeast Asia died, victims of disease and starvation.

Defence debacle

The only problem was that Singapore had all its defences pointing out to sea, while the Japanese, in a legendary manoeuvre, chose to invade it by land from the north, via Malaya. The Japanese 25th Army was led by Tomoyuki Yamashita, whose well-known discipline was said to be “rigorous as the autumn frost”.

Japanese aircraft raided Singapore on 8 December 1941, the same day they devastated US ships and airfields in Pearl Harbor. When informed, Governor Shenton Thomas told Lieutenant-General A. E. Percival, “Well, I suppose you’ll shove the little men off.”

Tamil workmen clear up debris in Singapore following a Japanese bombing raid in 1941.

TopFoto

His nonchalance proved misplaced. The Japanese quickly established land and air supremacy, taking two British Royal Navy battleships. They pushed southwards through the Malayan jungle paths. Percival, realising his northern border was unprotected, grouped the last of his troops along the northeast coast. The Japanese, in collapsible boats and other makeshift vessels, cut around the northwest flank and invaded Singapore on 8 February 1942.

Reign of terror

After days of heavy shelling by the Japanese, Percival surrendered unconditionally. Prime Minister Winston Churchill called it “the largest capitulation in British history”, while Yamashita, as he later wrote, attributed his success to “a bluff that worked”. In fact, the Japanese troops were outnumbered more than three to one by the island’s defenders.

The Japanese reign of terror began with the renaming of Singapore as Syonan – “Light of the South”. The Chinese were singled out for brutal treatment, with many killed, imprisoned or tortured for the flimsiest of reasons. The Europeans were classified as military prisoners or civilian detainees, while the Malays and Indians were urged to transfer their allegiance to Japan or be killed. Syonan’s economy deteriorated. Inflation skyrocketed, food was scarce and corpses were a common sight on the streets.

The formal British surrender to the Japanese, 1942.

National Archives of Singapore

On 21 August 1945, the Japanese surrendered and the British returned in September. But Communist resistance to the Japanese had changed the political climate. The people had plans for their own destiny and the British would no longer write the rules.

“Neither the Japanese nor the British had the right to push and kick us around,” recalled Singapore’s former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, in 1961. “We determined that we could govern ourselves and bring up our children in a country where we can be a self-respecting people.”

British policemen on the streets in 1946.

Getty Images

The nationalistic itch among Singapore’s population was not ignored by the British. One year after their return, the British ended their military rule of the Straits Settlements and set up separate Crown Colonies in Singapore and Malaya. The new governor instituted a measure of self-government on the island by allowing for the popular election of six members to a new 22-member Legislative Council. Elections were set for 1948.

The Emergency

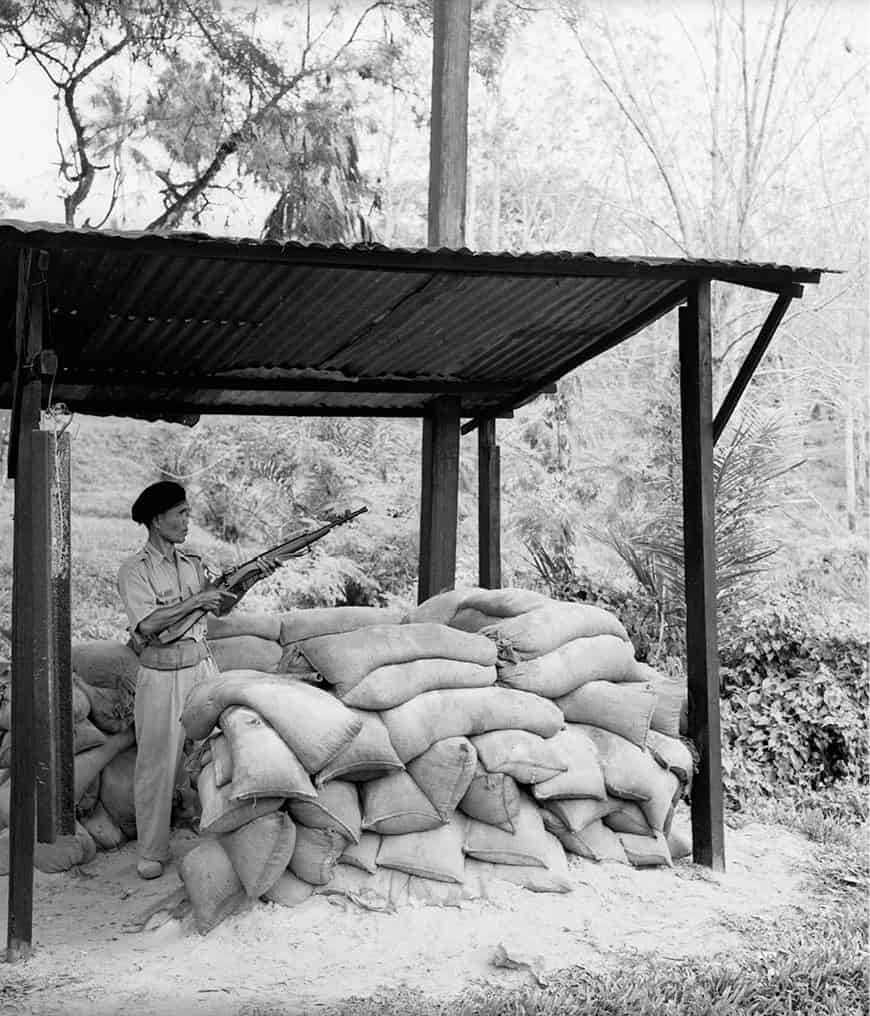

The Japanese defeat and the restoration of British colonial rule to Malaya and Singapore did not go unchallenged, particularly by Communism. The Malayan Communist Party (MCP) had emerged from World War II with new-found strength, having built up its prestige as a patriotic resistance movement during the Occupation. It now sought to infiltrate the labour movement by inciting unrest to overthrow British imperialism and establishing a Communist state. This organised insurrection of the MCP from 1948 onwards was termed the “Emergency”.

The MCP had its headquarters in Singapore, with branches in other Malayan towns. It operated through its General Labour Union cells to mobilise support among the workers and to gear the trade unions to its political ends. Attacks were launched in 1948 against European and local managers in tin mines and rubber estates to disrupt the economy and instil a climate of fear. In response, the British promulgated Emergency regulations in June 1948 that sanctioned arrest and detention without trial. They also initiated a campaign to win over the civilian population to erode the MCP’s base among the populace, particularly the Chinese. The Communist insurgency began to lose steam by 1953, but it was only in 1960 that the Emergency officially ended.

Independence

Even before the war had ended, political activity had begun in Singapore. In 1945, the Malayan Democratic Union was formed with the goal of ending colonial rule, and merging Singapore with Malaya. Merdeka – Malay for independence – was the rallying cry. The first election in 1948 was a lacklustre affair, with a slim turnout and only 13,000 votes cast. The Chinese majority was sidelined in favour of the English-speaking minority, an unequal state of affairs that would later steamroll the Communist insurrection known as the Emergency (see box).

Confrontation

The merger with Malaysia caused faultlines to appear not only on the domestic front but also on the international scene, with Indonesia. As leader of Southeast Asia’s largest Muslim state, President Sukarno was opposed to the Malaysian Federation.

To destabilise it, he initiated a policy of coercive diplomacy from 1963–6 that amounted to an undeclared war against Malaysia, known as the Konfrontasi. Although the confrontation was fought along the Indonesia–Malaysia border, it spilled over into Singapore, with Indonesian saboteurs infiltrating the island in 1964 and setting bombs in public buildings to create panic; the most serious explosion, in the MacDonald House in 1965, killed three. Confrontation ended with Sukarno’s downfall in 1966.

A British review recommended that all citizens be automatically registered to vote and that a Legislative Assembly with 32 members – 25 elected – be established with broadened powers. The constitution was enacted in early 1955 and, later that year, Labour Front member David Marshall was elected Singapore’s first chief minister. He led an all-party delegation to London the following year to negotiate complete independence from the Crown. He returned home empty-handed and resigned as he had failed to keep his merdeka promise.

David Marshall, Singapore’s first chief minister, negotiating with Malaya’s Tunku Abdul Rahman.

Straits Times Archives

Lim Yew Hock of the Singapore Labour Party took over as Chief Minister and made another bid in London in March 1957. The second delegation – which included a People’s Action Party (PAP) member and a young Cambridge-educated lawyer named Lee Kuan Yew – accepted roughly the same terms Marshall had been offered: a fully elected Assembly of 51 members, no power over external affairs and representation on – but not control of – an internal security council.

Back home, the Legislative Assembly ratified the terms and, in 1959, the British parliament passed an act approving the new constitution. The general election was set for May. The PAP won a sweeping victory and Lee Kuan Yew became Singapore’s first prime minister, a position he would hold until 1990.

Singapore sand-bagged guard post protecting against some 3,000 Communist-led bandits, 1950.

Corbis

The Singapore River in the 1950s with large commercial houses in the background.

Corbis

The PAP takes charge

The new government immediately set about reviving the economy, which had been suffering from a steady decline in entrepôt trade, as Singapore’s Asian neighbours increasingly took charge of their own trade. The PAP aimed for diversification: it beckoned multinationals with tax breaks, promises of protection against nationalisation of private enterprise and other attractive terms. A push on manufacturing also began.

The PAP’s main concern was the abolition of colonialism. Exactly what form this would take caused a bitter split in the party. The PAP was divided into two wings – the relatively moderate, English-speaking social democrats (Lee Kuan Yew’s wing) and the fiery, Chinese-educated Communists. The moderates were eager to join up with Malaya for independence – an approach approved by the electorate, which in a referendum in 1962 voted overwhelmingly for a merger.

Merger offered both raw materials and a wider market for Singapore’s industrial products. An independent Singapore, Lee said at the time, with no raw materials and no appreciable internal market, was “a political, economic and geographic absurdity”. The right-wing Malayan government would support the moderate Lee in his struggle with Singapore’s leftist opposition Barisan Socialis. However, Malaya feared that absorbing Singapore’s one million Chinese would adversely affect the balance of power in its Malay-dominant territory. But the greater evil of an “Asian Cuba” at its doorstep persuaded the anti-Communist Malayan prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman to offer unification.

Lee Kuan Yew making a speech in 1959.

Getty Images

The merger took place on 16 September 1963. To balance the influx of Chinese from Singapore, the British colonial states of Sarawak and Northern Borneo (Sabah), with their largely indigenous Malay populations, also joined the Federation of Malaysia.

Within a week, the PAP held a general election, catching the opposition by surprise. Riding on the fresh success of the merger, the PAP won 37 seats against 13 for the Barisan Socialis. Almost immediately, the PAP arrested and detained 15 opposition leaders. This move decimated the Barisan Socialis, and was explained away by the PAP as necessary to wipe out the “Communist plot to create tension and unrest in the state”.

The PAP entered the Malaysian political scene aggressively by insisting on an immediate common market, meeting head-on with Malaysian resistance. This was just one example of the tension-ridden differences between Singapore and its federation partners.

Divisive differences

But far worse was the racial tension. The PAP’s foray into federal politics was viewed by Malaysia’s Malays as a Chinese bid to challenge Malay supremacy. The discord culminated in two major race riots in Singapore between Malays and Chinese in July and September 1964, setting the stage for a split. On 9 August 1965, Singapore was expelled from the federation, and became independent. The next month, the island nation became a fully-fledged member of the United Nations.

For Singaporeans, independence was a matter of worry, not joy. How could this tiny state survive, surrounded as it were by giant unfriendly neighbours? Britain was to vacate its Singapore base – part of a general withdrawal of troops from east of Suez. For Singapore, this prompted economic concerns as much as security worries: the British bases accounted for some 20 percent of its GNP and employed a good chunk of the labour force. When the British left in 1971, Singapore introduced compulsory two-year national service for all 18-year-old males. Today, it has all the trappings of a modern-day fighting force, including an arsenal of sophisticated weaponry.

The newly independent country was also faced with high unemployment rates, inadequate housing, no natural resources and little cash. It also lacked national cohesion, being essentially a disparate group of immigrants comprising the majority Chinese, and Malays, Indians and Eurasians. However, the fledgling state still had a few aces up its sleeve.

Its strategic location made it an established trading hub and it had inherited British rule of law. The other ace was the pragmatic – some would say ruthless – Lee Kuan Yew, who provided vision and the necessary drive. His government took to heart the basic economic premise that to attract foreign investment, a developing country had to offer political stability, cheap labour, a good location, and few or no restrictions on currency movement. As a result of his efforts, Singapore’s industrial sector grew 23 percent a year from 1968 to 1972 – one of the highest rates the world has seen.

Politicians’ big pay packets

Singapore may be a small country, but when it comes to paying its leaders, it’s in the big league. Prime minister Lee Hsien Loong earns about US$1.7 million a year, while a cabinet minister in Singapore earns close to US$1.2 million. Singapore has the highest-paid leader in the world; the US president earns a mere US$400,000. Such high wages are due to Singapore’s free-market philosophy of paying its ministers salaries competitive with top executives in the private sector. Only in this way does it expect the best brains to join the civil service. Needless to say, this is an area of much contention.

Nimble economic strategies

This growth was spurred by careful and farsighted economic planning. Singapore has always adhered to an open market economy. Each decade threw up its challenges, which the country overcame effectively. In the late 1960s and 70s, its capital and skill-intensive industries laid the groundwork for the entry of electronics giants such as Sony and Matsushita.

When the 1980s demanded knowledge-intensive industries, Singapore had in place by the decade’s end a base of manufacturing capabilities. Companies undertook research and development, engineering design and software development. The upwards trajectory continued in the 1990s, with forays into Vietnam, India and China. Realising that it could not compete with other Asian countries in labour-intensive industries, Singapore aimed to be a world-class IT hub and Southeast Asia’s banking and financial centre. The decade after the turn of the millennium, life sciences were identified as an engine of growth, while tourism received a boost with the opening of two “integrated resorts”, mega-entertainment and leisure complexes complete with casinos, in 2010. As a result, Singapore has the third highest GDP per capita in the world.

Along with economic growth, public housing was a top priority (for more information, click here). Today, more than 87 percent of the population live in comfortable government-built Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats which they own, using funds from a compulsory retirement savings programme called the Central Provident Fund (CPF) to finance most of the mortgage.

At Singapore Science Festival in 2013.

Getty Images

The Marina Bay Sands complex.

Dreamstime

The PAP at the helm

Over the decades, the PAP has proved itself a sturdy government able to deal decisively and competently with crises of different shapes and sizes: the 1970s oil crisis, the 1985 economic recession, the economic downturn of the late 1990s and the 2003 SARS epidemic.

If its increasingly sophisticated people chafe under a paternalistic style of government, such sentiments have hardly been reflected in the polls. The PAP, re-elected continuously since 1959, has only suffered a tiny hiccup in its history of political dominance – at the 1991 general election it lost four seats to the opposition, instead of the customary one or two.

Prime minister Goh Chok Tong, whose rule saw some political and social liberalisation in the last decade, retired in 2004, giving way to his deputy, Lee Hsien Loong, the eldest son of former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. There were concerns that the younger Lee may return to the more autocratic style of his father, but the critics have been proven wrong thus far.

Parliament at work

Singapore has a system of parliamentary democracy, where members of parliament are voted in at regular general elections. The “life” of each parliament is five years from its first sitting after an election.

In the 1990s, nominated members of parliament (NMPs) were introduced – unelected members chosen by the parliamentary select committee. The aim is to allow citizens with no party affiliations to contribute to parliament. However, to date there’s only been one legislative initiative from an NMP – in 1995, university lecturer Walter Woon introduced the Maintenance for Parents Bill, the first bill passed initiated by a non-PAP member.

In late 2004, he revealed the proposal to build two “integrated resorts”, at Sentosa and Marina Bay. There were concerns that the casinos in these resorts would encourage gambling, so Lee suggested that safeguards should be implemented. As a result, Singaporeans and permanent residents pay an entrance fee of S$100 per visit or S$2,000 annually.

Both these integrated resorts were opened in 2010, just as Singapore came to the end of the global recession in 2009. The island recovered quickly from this, with close to 15 percent growth achieved in 2010 – the highest annual figure on record. However, in 2015, the GDP growth rate in Singapore stood at 2.1 percent, a slowdown on the previous year, continuing the trend since 2010, albeit from a high level.

In the 2011 general election, the PAP’s vote tally went down compared to previous years. It won 81 out of 87 parliamentary seats and only 60.1 percent of the votes compared with 67 percent in the 2006 election. The cause of this was that citizens were unhappy with immigration policies that allowed hundreds of thousands of immigrants and foreign workers into the country, causing competition in the job market, home prices to escalate and public transportation to be overcrowded. With this wake-up call, between 2012 and 2013, Lee Hsien Loong responded to the criticism and called for the tightening of immigration policies and controlling housing costs. Even so, Singapore is still ranked by the World Bank as the easiest country to do business. It also has the highest proportion of millionaire households. In the 2015 elections, the PAP won 83out of 89 seats.

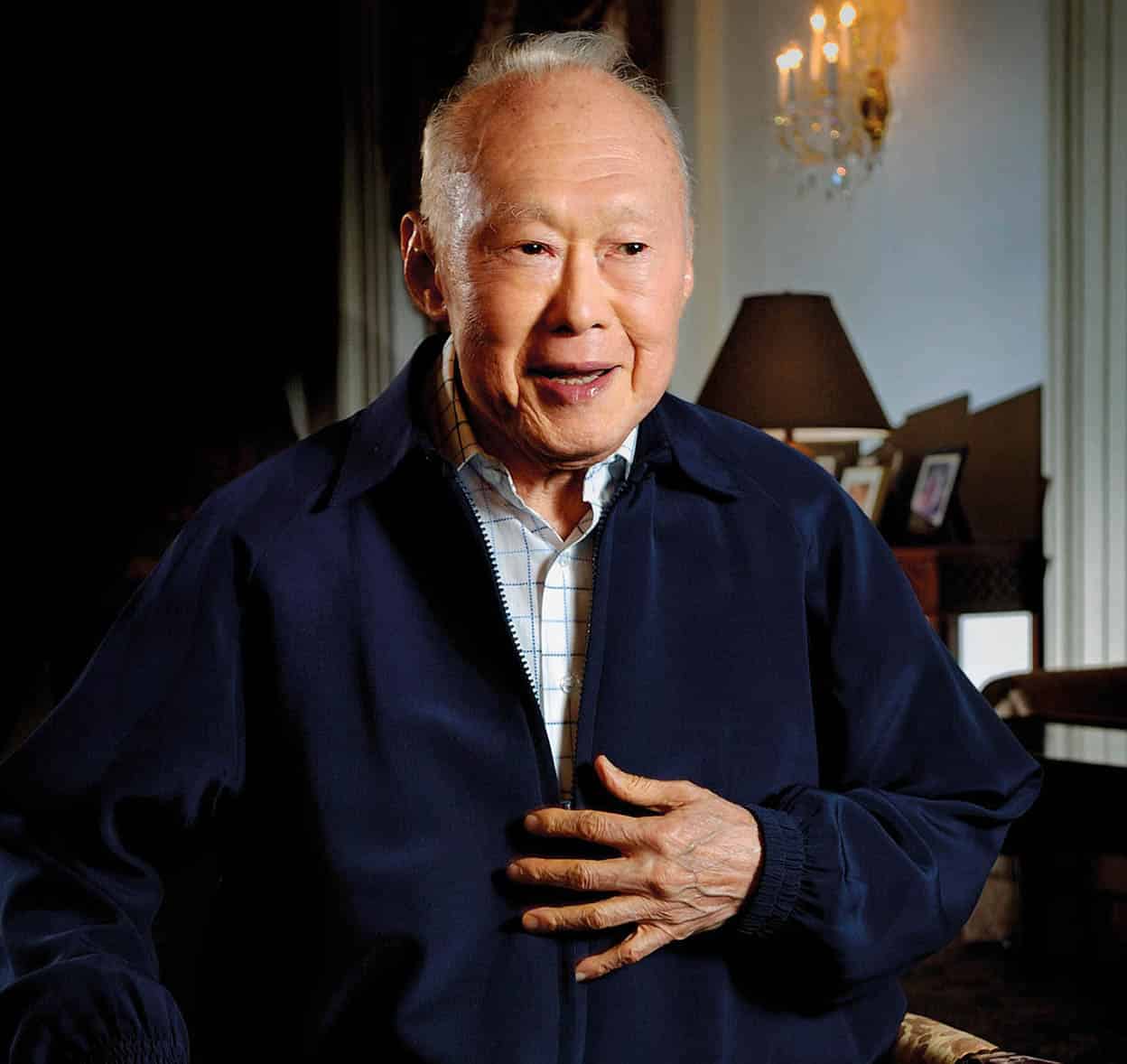

Lee Kuan Yew

The father of modern Singapore had his share of criticism, but no one can deny that he was responsible for its roaring success.

He stepped down in 1990 as Singapore’s first prime minister, but until his death, Lee Kuan Yew remained a political force to be reckoned with. The Cambridge-educated, fourth-generation Singaporean was credited with shaping a tiny island comprising a disparate group of immigrants into a gleaming model of efficiency.

Lee was born on 16 September 1923, when Singapore was still a British colonial outpost, to a father who worked for oil giant Shell before retiring to sell watches and jewellery. The eldest of five children, Lee topped candidates from the Straits Settlement and Malaya in the Senior Cambridge School Certificate examination in 1939 to win a scholarship.

A strong legacy

The story of how Lee Kuan Yew transformed Singapore is fascinating because no other leader in the modern world has had such a hand in influencing and directing his country’s progress, right from independence to developed-nation status.

Lee helped found the People’s Action Party (PAP) in 1954, shrewdly representing its moderate faction while the party itself courted the Chinese majority on an anti-colonial left-wing ticket. He was prime minister for 31 years until 1990, when he handed the reins over to Goh Chok Tong. While admired for his grasp of a wide range of issues and especially for his social and economic vision, Lee’s uncompromising attitude and his critical, often intimidating, personal style was not always well received.

He has been described as autocratic, high-handed and authoritarian, with foreign critics describing Singapore’s political system as intolerant. Still, it is undeniably a system that works, and the country’s rise to affluence remains the greatest testament to Lee’s personal beliefs.

Lee instilled good governance and bureaucratic efficiency, and dealt harshly with corruption while building modern ports, a top airport and other infrastructure to lure foreign investors. To compensate for the lack of local manpower (on top of low birth rate), he implemented a policy of attracting foreign workers, including top corporate managers and professionals. This has unfortunately caused resentment amongst citizens as they face challenges and competition in the job market. In 2011 after the PAP had the worst electoral showing since independence, Lee resigned from his cabinet position

Lee’s last book, titled One Man’s View of the World, created controversy across the causeway as he mentioned that Malaysia’s race-based policies had caused an acute brain drain and put the country at a disadvantage. Despite all that, his views on Asia’s emerging role in the world economy continued to be sought by other world leaders, and in 2010 he appeared on the TIME 100 list of the most influential people in the world. Lee died in March 2015 of severe pneumonia, aged 91.

Lee Kuan Yew.

Getty Images