The House of Bugs

Learn about your gut

CASE: A 56-year-old woman with diabetes was recently admitted to the hospital for persistent, foul-smelling diarrhea. Recently, she had recurrent urinary tract infections and had been prescribed multiple courses of antibiotics. She was losing weight and had low energy. She was diagnosed with C. difficile colitis (an infectious inflammatory overgrowth in her gut) and was given more antibiotics to heal the infection of her gut. Despite multiple attempts at curing the infection, her diarrhea became intractable. She was given a fecal transplant, which is when the stool of a healthy family member is placed through a scope into the gut of the ill family member. Within weeks, the patient felt better; she was eating and no longer had diarrhea.

Learning about the gut is extremely important. It turns out that the gut has loads of bacteria in it. Those gut bugs are responsible for much of the immune system defense of our bodies and have a role in hormone and mood regulation. Those bugs also seem to have a role in decreasing inflammation and potentially a role in what illnesses we get. Before we go on, let’s go over some definitions.

Microbiota is the term that refers to all of the microorganisms (tiny bugs) in our bodies that are exposed to the outside surfaces. This includes the gastrointestinal organs (mouth to anus), skin, nose, ears, and genitals. These microorganisms are bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and even viruses that inhabit our bodies. It is estimated that 90 percent of cells (approximately 100 trillion cells) found in our bodies are not human, but come from 40,000 bacterial strains. Imagine, then, that we are only 10 percent human and the remainder is bugs!

Microbiome refers to the entire gene pool found in our bodies. Recall that genes are the instructions in cells that decide our appearances, what our personalities are like, and what health conditions we will get in our lives. Genetic material lives in all of our cells and is called our genome. There is also genetic material that comes from every bug in our guts. Some people call the gut our “second genome” or our “second brain” because of all the genetic material that comes from our bugs. Not only are the human genes outnumbered by the genetic material from our microbiota, but these gut bugs likely have a significant impact on our health as well.

The human microbiome project is a project funded by the National Institutes of Health. The project focuses on understanding the role of the microbiome in our bodies. It has given us a lot of important information on the role of the gut in how we feel and how we respond to illness. From this project, we know that the microbiota plays a critical role in building and maintaining our immune systems. Many people call the gut the “internal health monitor.” It is responsible for monitoring bacteria and viruses that come into the mouth with everything we eat and preventing those infections from getting into our bloodstreams and becoming systemic diseases. The gut is involved in the production of vitamins, essential amino acids, and fatty acids. It also impacts how our bodies utilize fats and sugars, which are important in understanding how we gain weight.1 (See Consider 1.)

CONSIDER 1

Having an intact microbiota directly impacts one’s health. Similarly, having a weakened microbiota puts one’s body at risk for illness. The proliferation of the wrong kind of microbiota may predispose us to autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and type 1 diabetes, as well as increasing risk of obesity, infections, and depression. It also likely impacts our risk for getting allergies.2 These microbial communities change as we age, and the type of bacteria that are present in these communities shift, based on our diets and exposures to various foods and antibiotics, which can lead to an over- or underproduction of certain microbes. Many of us believe that this second genome plays a crucial role in deciding how healthy, or how sick, we will be.

How is the Microbiome Created?

When we are born, we go through our mothers’ vaginal canals (the birth canal) and are exposed to our mothers’ microbiomes. We know that when a baby is born by vaginal delivery, the bugs from the mom’s vagina populate the baby’s gut. We also know that if a baby is born via cesarean section, the bugs from the mom’s skin populate the baby’s gut. We know that the composition of the gut bugs change based on if the baby is breastfed or formula fed, whether the baby received rice cereal or was given antibiotics for an infection.3,4 Babies then crawl on the floor and suck on their toys. They are exposed to other people, our pets, and our plants, all of which are covered in bacteria and nourish their gut. They go outside and are exposed to dirt with all of its valuable microbes. They eat the grass and lick things that our pets have licked, and they obtain more bugs. Exposure to small numbers of pathogens will strengthen our immune system. Our gut bugs also change in composition and proportion, though, depending on whether we develop an illness, on whether we take antibiotics, and on what we eat. We are just on the brink of understanding what all these changes mean and which changes are good and which ones are bad. (See Consider 2.)

CONSIDER 2

The Ps and Fs: Prevotella and Firmicutes

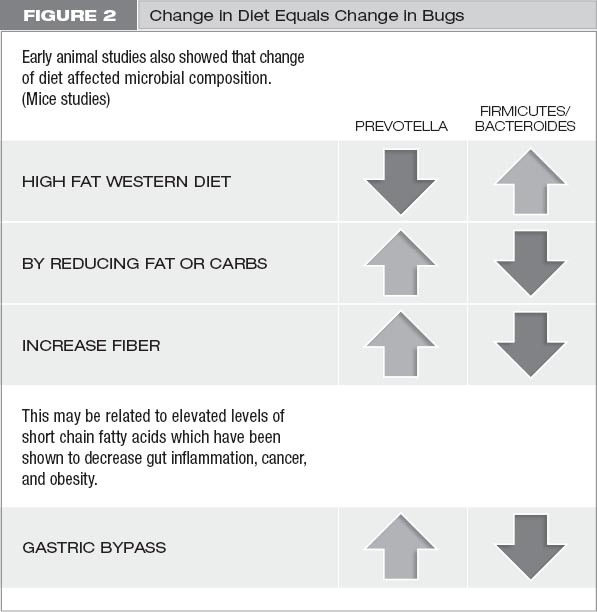

There are millions of bugs in our gut, and we don’t know much about most of them. However, there do appear to be several principal types of gut bugs that change with diet in some studies. Prevotella and Firmicutes are two classes of gut bugs that change in number based on what we eat. We know that when we eat high-fat foods, we have more Firmicutes than Prevotella. When we reduce fat or carbohydrates, we increase Prevotella and decrease Firmicutes. When we eat fiber, we increase Prevotella. When we go through gastric bypass surgery, we increase Prevotella.

A study was done that looked at rural Africans and African Americans.5 The rural Africans ate a village diet that was mostly plants, high in fiber and low in animal products. The African-American diet was high in animal fat, low in plants, and low in fiber. Interestingly, the Africans had a Prevotella predominance in their guts, and the African Americans had a Firmicutes predominance in theirs. The study went further, which is the best part. Researchers found that the African Americans had more colonic inflammation and the Africans had less. Then the researchers switched the diets of the two groups, and they found that the bacterial predominance shifted. The Africans developed a Firmicutes predominance, and the African Americans had a Prevotella predominance. And on top of that, colonic inflammation increased in the Africans after the diet switch and colonic inflammation decreased in the African Americans!6 How cool is that? (See figure 2.)

Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Another important concept to note is that when bacteria break down food, they release short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). Three main SCFAs are butyrate, acetate, and propionate. We know that SCFAs are associated with decreased inflammation and are antineoplastic (anticancer causing). In the study with Africans and African Americans noted in the previous section, the Africans produced a higher number of SCFAs, which then decreased as they shifted to eating the diet lower in fiber and higher in meat! Plant-based foods were associated with higher numbers of SCFAs.6

Metabolites of the Gut Bugs

There are many metabolites (substances needed for metabolism or created during metabolism) that are produced by bacteria in the gut. One of those metabolites is trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), which is produced when foods that are high in phosphatidylcholine are ingested. The main sources of phosphatidylcholine are eggs, liver, beef, and pork. When these types of food are ingested, they are processed in the gut and the metabolites trimethylamine and TMAO are formed. In a study done at the Cleveland Clinic, researchers found that elevated levels of TMAO were associated with increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.7 Much work is still needed in this area to understand the causality of this increased event rate, but, boy, it is interesting. The best part of the study to us was that the researchers also gave meat to vegetarians and vegans, and after ingestion of the food, they did not have the same increase in TMAO as the omnivores. Is this because the gut bugs in vegetarians and vegans are different from meat eaters, and, therefore, they had a different response? Much to consider here.

Another metabolite produced in the gut is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), another by-product of bacterial processing. The gut bacteria make LPS in response to a high-fat diet, which then triggers a leaky gut (more on leaky gut on pages 41–45).8 Harmful infectious bacteria can also carry high amounts of LPS. Antibiotics that decrease bacterial overgrowth also decrease levels of LPS. Similarly, certain prebiotics (foods for gut flora) and probiotics (actual bugs that come from food or supplements) also decrease LPS. In a study of 7,000 people with diabetes, it was found that their levels of LPS were higher than in nondiabetic individuals.9 When mice on a high-fat diet were given probiotics, their levels of insulin resistance decreased, as did their levels of LPS.10 We know that a proportion of SCFAs similar to those in rural African children can suppress lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other proteins that indicate inflammation (cytokine-triggered pro-inflammatory markers).9 Importantly, high levels of LPS have also been noted in Alzheimer’s disease and autism compared to healthy controls.11,12 (See Consider 3.)

CONSIDER 3

The Leaky Gut

Along with gut bugs, there is more to this story that is also being revealed: leaky gut or intestinal permeability. The gut consists of the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and rectum. It has a surface area of 3,000 square feet. It is on the surface of the gut that these microbes, or gut bugs, live. The more surface area that is present, the better our ability is to absorb and digest. The gut is also made up of an abundance of intestinal villi, which are outpouchings or protrusions in the colon that are responsible for absorption. The external layer of cells of these villi is our first line of defense, as these cells are the first to be exposed to whatever comes into the GI tract. They are the pawns on our chessboards and the infantrymen in our cavalry. (See figure 3 on the next page.)

These cells are followed by the intestinal dendritic cells, which resemble tiny trees branching out; they are often considered the first responders. These cells are the “soldiers on horses.” They are more equipped to handle the entry of a pathogen. Between these cells are tight junctions, like a barricade that prevents infections from getting through. But if those junctions break and an intruder gets in, immune cells (the T and B cells) arrive, which are active immune fighters. These cells are “the snipers and our ‘Navy SEALs.’” They are the best of the best, ready to attack any foreign material that invades our bodies. As Harvard professor and pediatric gastroenterologist Dr. Alessio Fasano says, “The intestinal mucosa [gut] is the battlefield on which friends and foes need to be recognized and properly managed to find the ideal balance between tolerance and immune response.” Normally, when hostile bacteria and viruses come through our intestines, we have a tight junction barricade and this large cavalry to handle the enemy, and the body deals with it with hopefully few casualties.

There are certain illnesses, however, where the tight junctions break and allow the bloodstream to be exposed to abnormal bacteria or bacterial by-products. Those abnormal by-products can then enter into the bloodstream and create an inflammatory response. A short response can be handled by the Navy SEALs without too much difficulty. But with a prolonged assault, this inflammatory response triggers formation of an abundance of inflammatory cells that can get out of hand and attack different parts of the host body.

An example of the leaky gut phenomenon is found in celiac disease, the study of which has been pioneered by Dr. Alessio Fasano. People with celiac disease have an allergy to gluten, which is present in wheat, rye, and barley. When people with gluten allergy eat gluten, their bodies respond poorly. Over time, they develop symptoms of malabsorption because their guts are unable to absorb any useful food particles—the gut is too massively inflamed. They don’t just manifest gut symptoms. Inflammation rages through their bodies. They develop diarrhea, abdominal pain, skin changes, and joint pain and can have neurologic manifestations.

Note that gluten allergy is different from gluten sensitivity. The immune changes with gluten allergy associated with celiac disease is an autoimmune reaction. This reaction can cause damage to the lining of the intestines. Gluten sensitivity can cause many symptoms, such as headache, joint pain, and fatigue, but sensitivity doesn’t necessarily damage the intestinal lining.

Dr. Fasano and others have shown that when people with gluten allergy are exposed to gluten, the tight junctions between their intestinal cells become leaky. The doors to the insides of their gut open. An environmental trigger, such as wheat in the case of celiac disease, then comes through the door and creates an immune reaction. Immune complexes form which then destroy the villi. Once destroyed, these villi cannot contribute to digestion and cannot help shunt essential nutrients into the bloodstream. Immune complexes create systemic reactions. Fasano believes that some level of leaky gut is a good thing. Most people have occasional intestinal permeability where the doors open for a short time. During that time, the immune system is exposed to foreign particles and learns to respond to them. But in celiac sufferers, the intestine is leaky for hours and the immune system becomes massively inflamed. As Fasano says, “Friend or foe: when there is a fight, there is always collateral damage, i.e., inflammation.” (See figure 4 on the next page.)

Some environmental triggers can make one person have a leaky gut for hours while another person has a leaky gut for just minutes. We now know that a person must have a genetic predisposition to a certain sensitivity. We can’t necessarily fix this predisposition because we get it from our parents. But it is only when the environmental trigger appears, however, that a person actually becomes sick. Then we can potentially eliminate the trigger, decrease the leaky gut, decrease inflammation, and treat the chronic disease. (See Consider 4 on page 45.)

Fasano and others believe that many autoimmune diseases are affected by food sensitivities and changes in the microbiome at an early age. The leaky gut has been associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as type 1 diabetes.13 Type 1 diabetes (different from type 2 diabetes, discussed earlier) is an autoimmune disease in which someone’s own immune system attacks insulin-producing beta cells. Without insulin, our bodies are unable to process sugars and convert them to storage in the form of fat. The link between how the leaky gut triggers immune reactions that attack the pancreas in some people and cause type 1 diabetes, and in others creates lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or multiple sclerosis is not clear. Each person has different genetic predispositions and environmental triggers. Importantly, there are other environmental triggers for inflammation beside diet and gut permeability; we can’t ignore the roles of stress and trauma, obesity, and smoking as important causes of total body inflammation.8

CONSIDER 4

What is unclear, however, is how much of a role the imbalance in gut bacteria has on triggering the leaky gut versus the role of genetic predisposition to some food sensitivity. In other words, will a food sensitivity alone trigger inflammation and illness in a genetically predisposed person, or do you also need dysbiosis (an unhealthy combination of gut bacteria)? We believe that you need the whole package: genetic predisposition, exposure to a sensitized food, and abnormal gut flora. Presumably, the gut flora changes based on what someone eats, and certain gut changes increase risk for a leaky gut. These gut alterations, and resulting high levels of LPS, also seem to be associated with increased intestinal permeability, and the host immune system eventually reaches a constant state of chronic inflammation.8 In one study, mice fed a high-fat diet exhibited higher permeability to small molecules and reduced or altered junction proteins. This means that mice fed a high-fat diet could not create tight adhesions between their cells; therefore, bacterial by-products were allowed to enter their bloodstreams.14 In chronic kidney disease patients, we see the same sort of significant bacterial overgrowth and dysbiosis, as in the mice and evidence of disruption of their intestinal barriers.15 We believe this is what happened to Dr. A. She had a genetic predisposition to disease. She had food sensitivity to dairy and abnormal gut flora: the perfect storm.

This information is groundbreaking but still in the early stages; however, it provides clues as to the first links between changes in the microbiota and intestinal permeability. The gut likely holds the key to so many inflammatory conditions. Studies are ongoing to link high-fiber diets to increased SCFAs and determine whether that diet will reduce inflammatory conditions.

But Wait, There is More?! The Gut-Brain Axis

There is even more to this story. While Hippocrates said back in 460 BC that all diseases begin in the gut, our understanding of its importance has been relatively recent. The gut-brain axis is a concept that was established in the 1880s and recognizes the connection between our brains and our guts, which occurs via the autonomic nervous system (the same nervous system we talked about previously). It consists of nerve branches that connect the brain to the other organsand is the control center for subconscious activity, such as breathing, swallowing, urinating, and digestion. The autonomic nervous system is divided into enteric (nervous system of the gut), sympathetic (fight or flight), and parasympathetic nervous systems (rest and recharge), which all play a role in regulating gastrointestinal function. These connections are established via the vagus nerve, which provides fibers from the brain all the way to the transverse colon. Stimulation of the vagus nerve causes not only variations in the heart rate, but also changes in gut motility. Gut motility is the activity of processing our food remnants into stool and removing all the important nutrients. Slow motility would suggest slow processing of food and can be witnessed as visible food contents in our stool.

As we discussed previously, when we are stressed, our sympathetic nervous systems become activated. Our senses become more acute. We see more clearly. Our hearing is more defined. We think more clearly. (See Consider 5.) Our heart rates increase so that our hearts can pump more blood to essential organs. Blood pressure increases and blood flow improves to the brain. Simultaneously, pain sensitivity is blunted, and bladder and gut motility slow down. When we are relaxed, the parasympathetic nervous system is activated. Our heart rates slow down and gut motility increases. This makes sense because if we are being chased, we need faster heart rates and elevated blood pressures. We need heightened senses and don’t want to worry about having to urinate or being hungry. We can’t worry about pain. When we are relaxed, our heart rates and blood pressures go down, and we become hungry. Our bowels and bladders work. We can focus on pain and deal with it. This is an important concept in gut motility, but it also becomes relevant when we talk about day-to-day stresses and ways to recharge.

While the link between the gut and brain has long been established, it is not entirely clear how the vagus nerve actually interacts with the microbiota. The link is likely related to neurotransmitters, hormones, and short-chain fatty acids that are produced by the gut. Neurotransmitters and hormones are chemical signalers or correspondents that come from the brain and travel to the gut, or vice versa. Tryptophan, for instance, is produced by the gut; it is involved in sleep function and is a main building block of protein. Serotonin, which is involved in mood, is produced in part in the gut. Most antidepressants are selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI), which means they prevent serotonin from breaking down. With serotonin, our moods are stabilized. Likewise, without serotonin, we suffer from depression. (See Consider 6.) Short-chain fatty acids, fatty acids produced by the gut, have been shown to improve memory and protect the brain. Only with more recent studies and ongoing research are we able to increase our understanding of the vagus nerve’s true impact.

CONSIDER 6

These studies on the gut-brain axis, usually done with mice, rely on a concept called “a germ-free host,” an animal that theoretically has no microbiota (no gut bugs). The host mice were delivered by cesarean section, were fed sterile milk, and were raised in a sterile environment to ensure they had no microbiota. Without a microbiota, the mice experienced significantly more anxiety-related behavior, repetitive movements, and decreased memory. Biochemical and molecular changes were also noted, such as in the level of cortisol (a stress hormone) and, amazingly, the functioning of some genes. Genes that affect learning and memory were altered in germ-free hosts compared to hosts with microbiota. Data suggests that when a normal microbiota is restored or probiotics are given to these hosts, many of the behavioral changes, such as anxiety, sociability, and other biochemical processes, can be reversed.16 This is an amazing concept. More studies and human trials are needed.

We previously mentioned that many metabolites produced by microorganisms in the gut are also neurotransmitters in the brain. Along with serotonin and tryptophan, histamine (which is involved in immune responses) is also produced by the gut. Dopamine is a chemical messenger that causes dilation of blood vessels. Tryptophan is not only a building block of proteins, but also another neurotransmitter, serotonin, which helps us sleep. These are all important metabolites produced by the gut. Interestingly, in one study, when the guts of germ-free hosts were recolonized, the levels of serotonin and social awareness in those hosts did not change, suggesting there is an age or length of time after which gut alterations have less of an impact.

The role of the microbiota can be seen in psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Autism is a neurocognitive disorder associated with decreased social skills (such as cognition) and sometimes repetitive movements. Genetic and environmental factors are believed to play a role in the development of this disease. A large number of people with autism spectrum disorder have associated gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. Studies vary, but we’ve learned that between 9 and 70 percent of autistic people have some GI concerns. There is recent data to suggest a link between autism spectrum disorders and the microbiota. Germfree mice have been shown to lack social skills and have demonstrated an increase in the repetitive behaviors often seen with autism spectrum disorders.17 Studies have shown that probiotics can decrease gut imbalance, improve these gastrointestinal complaints, and decrease immune system abnormalities. Whether probiotics can improve behavioral issues remains to be seen, and large randomized controlled trials are needed.17

We have now seen how our gut flora plays a very important role in how we feel. We also know that exposures from childhood are important for keeping these bugs strong and ready to attack. We have learned that in modern times the bugs in our guts have changed because of antibiotic use and perhaps highly improved sanitary conditions. (See the section on hygiene on pages 49–50.) We have shown that the foods we eat can modify our gut flora, and by-products of less nutritious foods have been linked to heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and autism. We also know that a whole-grain, plant-based diet helps the composition of our microbiota to shift, so that we produce more of the SCFAs that are pivotal in maintaining a strong immune system and better overall health. Once again we see an important benefit from this diet. (See Consider 7.) All and all, the data on the microbiome is ever-expanding. We have the framework linking chronic illnesses and the microbiome, and as more of these studies are done, the treatments of chronic illness also will change.

CONSIDER 7

We may not be able to control our genetic predispositions, but we can control our environmental triggers. We can control what we eat. Common food sensitivities believed to be triggers for leaky gut are animal products, specifically red meat, dairy products, processed foods, and gluten. All of these will be discussed later in this book. Often, treatment of many autoimmune diseases has to start through the process of elimination, discovering which environmental triggers a person is susceptible to. This concept is the foundation for diet modifications that we recommend.

Hygiene Hypothesis

Sanitation is very important. There is no question. Proper hand-washing techniques have significantly reduced infection rates globally. Over time, however, our behaviors have changed as explained by something called the hygiene hypothesis. Because we are more aware of the importance of sanitation and its role in infection, we tend to clean and sterilize most everything. We know that sanitation prevents the spread of germs, and because of this knowledge, we have reduced the number of illnesses that have affected our children. But have we gone too far? Is it possible to be overly clean? What is the impact of hand sanitizers and antibacterial soaps that remove 99 percent of the bacteria on our skin? Is that a good thing? In fact, studies show that people who lived in large families in less sanitary conditions than we do today were not afflicted with the same illnesses that we are now. They had less asthma and fewer allergies.18 Have you considered how many people you know who have a peanut allergy? In the past, this was nonexistent.

With greater access to medical care, we also take our children to doctors when they have common ailments. Often people go to their doctors’ offices with colds and want antibiotics. But most of the time, these so-called colds are caused by viruses, and antibiotics are primarily ineffective against viral infections. But perhaps because of pressure from their patients, physicians will prescribe antibiotics anyway, which then disrupt their patients’ gut flora. Are we doing the right thing?

Are we overtreating illnesses, and could many of them simply be monitored while our bodies’ natural defenses go to work? With all of these changes in the modern era, we have also noted the onset of so many more cases of allergy, autoimmune disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.19

Many health professionals (and we ourselves) also assert that we should let natural things be natural. Their advice includes the following: Do not stop your kids from eating dirt, as long as it hasn’t been sprayed with pesticides. Let them get dirty. Let your dog lick the kids’ faces. Don’t spray everything with bactericidal soap. Don’t wash your hands with bactericidal soap or use alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Unless we work in a hospital or are constantly exposed to infections, the bacteria that we are exposed to are good for our microbiota. Our intestines become strong and hardy, and the intestinal barriers become strong. Nourish your bugs. Don’t be afraid of them.

Probiotics

Probiotics have been defined as “live organisms that when given in adequate amounts confer health benefits.”20 Probiotics have received a great deal of attention lately. This interest started with recent studies on lactose intolerance, which is the inability of the body to break down lactose, a key component of cow’s milk. As we age, the amount of lactase enzyme we produce in order to break down lactose decreases. As a result, with lactose malabsorption, people experience bloating, gas, and watery diarrhea. It has been discovered that giving those same people yogurt that contains live probiotic cultures can reduce their intolerance.21

Gastroenterologists and scientists have started looking at what it is about yogurt that allows people to tolerate it better than milk. In yogurt production, milk is fermented, which causes the production of lactase. Several types of bacteria are produced in yogurt cultures; two beneficial strains in particular are Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. Thermophilus.22 Multiple studies have shown that ingestion of variable quantities of yogurt decreases lactose malabsorption and improves tolerability. In acute diarrheal illnesses, other strains of Lactobacillus have been used for treatment.

In one important study, 287 children under three years of age with acute diarrhea were given a probiotic with oral rehydration therapy versus the rehydration therapy alone. Those who received the probiotic had shorter, less severe illnesses.23 Also, importantly, in multiple studies, people who took probiotics while traveling were protected from traveler’s diarrhea by almost 50 percent.24 Different strains of good bacteria were used in the various studies, and a number of them were found to have benefits.

The most interesting work on probiotics extends beyond use in gut-related illnesses. In one study, pregnant women were given probiotics prior to delivery and during the period they were breastfeeding; if their babies were formula-fed, the probiotic was supplemented into the diet of the newborn. The children who had received the probiotic showed a 50 percent reduction in the amount of their eczema, and that improvement lasted for up to four years postdelivery.25 There is also data available on decreases in dental caries (cavities) when subjects were given probiotics. Probiotics likely also play a role in improving inflammatory bowel disease.26 Many animal studies, as well as studies done on small numbers of humans, show a role of probiotics in lessening symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis sufferers.27,28 New studies show the potential benefits of probiotics in inflammatory overall diseases by reducing intestinal permeability and protecting against bad bugs finding a home.29

The action of probiotics provides us another compelling way to recognize that healing the gut heals the body. Replenishing the gut with needed healthy bacteria can decrease the overactive immune agents that develop with common infections and potentially in inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and eczema and possibly inflammatory bowel disease and diabetes. Healthy gut bacteria may play a role in cancer abatement as well.

We believe that there are significant benefits to probiotics. We use them in our clinics and with our patients, depending on the case. The problem with over-the-counter probiotic supplements is that there is a lot of variability in the type and amount of bacteria that are used. Plus, there is no Food and Drug Administration safety checking of these products. We often recommend foods containing natural probiotics, such as sauerkraut, kimchi, and tempeh, to be added to the diet—especially when the gut is very sick. Think about how you can get some of these natural probiotics into your life.

Summary

1.The microbiome has a connection to the other systems in our body. It has a role in how we feel, how hungry we are, and how we respond to illness.

2.Our exposures affect the strength of our guts. We should not be afraid to get a little dirty because it nourishes our gut bugs.

3.Our diet is a trigger for many changes in the gut and puts us at a potential risk for illness.

4.Plant-based foods trigger production of more SCFAs, which are important for our immune systems and for decreasing inflammation.

5.Natural probiotics have a role in nurturing the gut.

YOUR PRESCRIPTION