7. Terror Camp Clear

By 1854 nine years had elapsed since Franklin set sail on his voyage of discovery. He had provisions for three years, though it was thought the supplies could have been rationed to last some months longer, perhaps until 1849. What became obvious to the Admiralty was that, regardless of what more could be done to solve the mystery, nothing could be done to save Franklin and his men. On 20 January 1854, a notice in the London Gazette stated that unless news to the contrary arrived by 31 March, the officers and crews of the Erebus and Terror would be considered to have died in Her Majesty’s service, and their wages would be paid to relatives up to that date. The expedition’s muster books show the sailors buried on Beechey Island, however, were “discharged dead” according to the dates on their headboards: William Braine on 3 April 1846, John Hartnell on 4 January 1846, John Torrington on 1 January 1846.

Despite the official acknowledgement that no more relief expeditions would be sent, interest in the Franklin search—and in the Arctic in general—remained high in Britain. Three Inuit (or “Esquimaux” as the Victorians called them) were taken to England by a merchant and given an audience with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, then “exhibited” in London. “The painful excitement which has so long pervaded the minds of all classes with respect to the fate of Sir John Franklin’s Arctic Expedition lends additional interest to the examination of these natives of the dreary North,” the Illustrated London News commented. Interest among North Americans did not always match that of the British public’s, however. In one instance, the Toronto Globe complained that only a handful of people attended a lecture on the Arctic and the possible fate of Sir John Franklin, while the same hall had been “filled to overflowing” with those curious to view the famous midget Tom Thumb.

Finally, on Monday, 23 October 1854, under the headline “Startling News: Sir John Franklin starved to death,” the Toronto Globe reported “melancholy intelligence” that had arrived in Montreal two days earlier. After his failed earlier investigations, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s John Rae had made the first major discovery of the Franklin searches while surveying the Boothia Peninsula. The Globe excitedly outlined the news:

From the Esquimaux [Rae] had obtained certain information of the fate of Sir John Franklin’s party who had been starved to death after the loss of their ships which were crushed in the ice, and while making their way south to the great Fish [Back] river, near the outlet of which a party of whites died, leaving accounts of their sufferings in the mutilated corpses of some who had evidently furnished food for their unfortunate companions.

Two days later, the Globe argued that Rae had succeeded “in revealing to the world the mysterious fate of the gallant Franklin and his unfortunate companions, and in proving the folly of man’s attempting to storm ‘winter’s citadel’ or light up ‘the depths of Polar night.’ ” By 28 October 1854, word had reached Britain that the veil that obscured the fate of Sir John Franklin had been lifted. In a letter to the Secretary of the Admiralty, Rae outlined his discoveries:

… during my journey over the ice and snow this spring, with the view of completing the survey of the west shore of Boothia, I met with Esquimaux in Pelly Bay, from one of whom I learned that a party of ‘whitemen’ (Kablounans) had perished from want of food some distance to the westward… Subsequently, further particulars were received, and a number of articles purchased, which place the fate of a portion, if not all, of the then survivors of Sir John Franklin’s long-lost party beyond a doubt—a fate terrible as the imagination can conceive.

Rae went on to report descriptions of a party of white men dragging sledges down the coast of King William Island, of the discovery a year later of bodies on the North American mainland and evidence of cannibalism. Contrary to the Toronto Globe headline, there was no proof that Franklin himself had starved to death, but disaster had clearly befallen his crews. Evocatively, the Inuit also told Rae that “they had found eight or ten books where the dead bodies were; that those books had ‘markings’ upon them, but they would not tell whether they were in print or manuscript.” When Rae asked what they had done with the books, possibly expedition logs, he was told that they had given them to their children, “who had torn them up as playthings.” In support of the Inuit accounts, Rae carried with him items he had been able to purchase from the natives, including monogrammed silver forks and spoons, one of them bearing Crozier’s initials, and Sir John Franklin’s Hanoverian Order of Merit.

Because Rae’s information about the cause of the expedition’s destruction came second-hand, it was judged inconclusive by many, though the relics were evidence enough that “Sir John Franklin and his party are no more.” The British government, enmeshed in the Crimean War, asked the Hudson’s Bay Company to follow up on the new information. Its chief factor, James Anderson, was able to add only slightly to Rae’s report when he discovered several articles from the Franklin expedition on Montreal Island and the adjacent coastline, including a piece of wood with the word “Terror” branded on it, part of a backgammon board and preserved meat tins—but no human remains or records. Anderson’s search, which lasted only nine days, would be the last official attempt to learn the fate of Franklin. Rae, though attacked by critics for not following up on the Inuit reports and instead hurrying back to London, was given £8,000 in reward money; the men in his party split another £2,000.

The British public and government interest quickly turned to the Crimean War. The very week that news of Rae’s discoveries reached Britain, a confusion of orders resulted in a brigade of British cavalry charging some entrenched batteries of Russian artillery. A report in the Times captivated Franklin’s nephew, the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who immortalized the encounter where so many British horsemen died in his “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” Events had finally overtaken the disappearance of Sir John Franklin and his officers and crews, leaving many to believe that the mystery of the expedition’s destruction would never be solved. In addition, there were others who questioned the value of research expeditions such as Franklin’s, which demanded such a heavy toll. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine summed up this view better than any other journal in an article published in November 1855:

No; there are no more sunny continents—no more islands of the blessed—hidden under the far horizon, tempting the dreamer over the undiscovered sea; nothing but those weird and tragic shores, whose cliffs of everlasting ice and mainlands of frozen snow, which have never produced anything to us but a late and sad discovery of depths of human heroism, patience, and bravery, such as imagination could scarcely dream of.

Yet there were still those who had not given up on Arctic expeditions, who still believed that the answers to Franklin’s fate lay somewhere on King William Island or on the mainland close to the mouth of the Back River. Foremost among them was Lady Franklin, who made one last impassioned plea to British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston: “… the final and exhaustive search is all I seek on behalf of the first and only martyrs to Arctic discovery in modern times, and it is all I ever intend to ask.” She failed to convince the British government to send one final search, and launched another expedition of her own. No longer seeking the rescue of Franklin, she now sought his vindication.

Jane, Lady Franklin, neé Griffin, aged twenty-four.

Lady Franklin, born Jane Griffin, personified the romantic heroine with her refusal to give up hope that searchers would one day discover the fate of her husband and his crews. Her determination, coupled with a willingness to spend a large part of her fortune to outfit four such expeditions, haunted the Victorian public as much as it inspired the searchers of her day. “To know a loss is a single and definite pain,” the Athenaeum observed, “to dread it is a complicated anguish which to the pain of the fear adds the pain of the hope… The misery is, that if the truth be not known, Lady Franklin will nurse for years her frail hope, almost too sickly to live and yet unable to die.”

What makes the devotion of Lady Franklin especially moving is the recognition that she was an independent and free-thinking woman who had not married until her thirties, and who saw more of the world than possibly any other woman of her day. During her long vigil, Lady Franklin not only implored the British for help, but the president of the United States and the emperor of Russia as well. She became an expert in Arctic geography. One famous folk song, “Lord Franklin,” captured the passion of her search:

In Baffin’s Bay where the whale-fish blow,

The fate of Franklin no man may know.

The fate of Franklin no tongue can tell,

Lord Franklin along with his sailors do dwell.

And now my burden it gives me pain,

For my long lost Franklin I’d cross the main.

Ten thousand pounds I would freely give,

To say on earth that my Franklin lives.

With the help of a public appeal for funds and a donation of supplies by the Admiralty, Lady Franklin purchased a steam yacht, the Fox, and placed command with the Arctic veteran Captain Francis Leopold M’Clintock, a Royal Navy officer who had been involved in three earlier Franklin search expeditions, beginning with that of James Clark Ross’s attempt in 1848–49. M’Clintock chose Lieutenant William Robert Hobson, son of the first governor of New Zealand, as his second-in-command. The Fox sailed from Aberdeen, Scotland, on 1 July 1857.

Almost immediately, problems hampered the search and the Fox was forced to spend its first winter trapped in ice in Baffin Bay, before being freed in the spring. By August 1858 the Fox had reached Beechey Island, where, at the site of Franklin’s first winter quarters, M’Clintock erected a monument on behalf of Lady Franklin. The monument, dated 1855, read in part:

To the memory of Franklin, Crozier, Fitzjames and all their gallant brother officers and faithful companions who have suffered and perished in the cause of science and the service of their country this tablet is erected near the spot where they passed their first Arctic winter, and whence they issued forth, to conquer difficulties or to die. It commemorates the grief of their admiring countrymen and friends, and the anguish, subdued by faith, of her who has lost, in the heroic leader of the expedition, the most devoted and affectionate of husbands.

By the end of September the searchers had travelled to the eastern entrance to Bellot Strait, where they established a second winter base. From there, M’Clintock and Hobson were able to leave their ship in small parties and travel overland to King William Island, early in April 1859. The two groups then split up, with M’Clintock ordering Hobson to scour the west coast of the island for clues while he travelled down the island’s east coast to the estuary of the Back River, before returning via the island’s west coast.

On 20 April, M’Clintock encountered two Inuit families. He traded for Franklin relics in their possession and, upon questioning them, discovered that two ships had been seen but that one sank in deep water. The other was forced onto shore by the ice. On board they found the body of a very large man with “long teeth.” They said that the “white people went away to the ‘large river,’ taking a boat or boats with them, and that in the following winter their bones were found there.” Later, M’Clintock met up with a group of thirty to forty Inuit who inhabited a snow village on King William Island. He purchased silver plate bearing the crests or initials of Franklin, Crozier and two other officers. One woman said “many of the white men dropped by the way as they went to the Great River; that some were buried and some were not.”

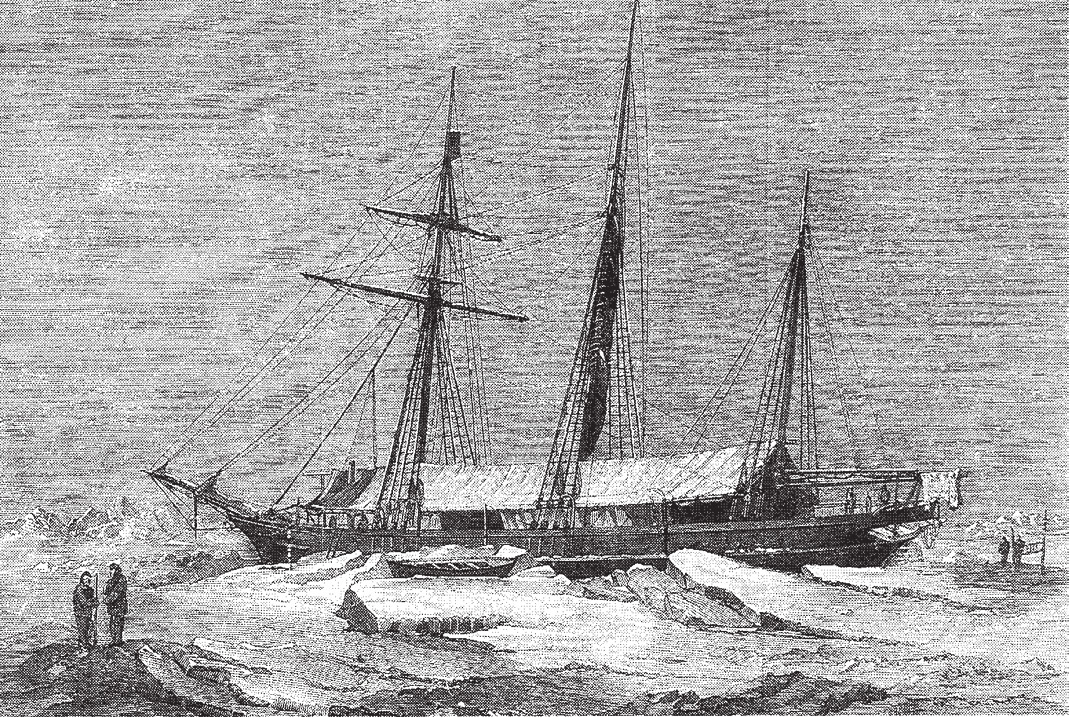

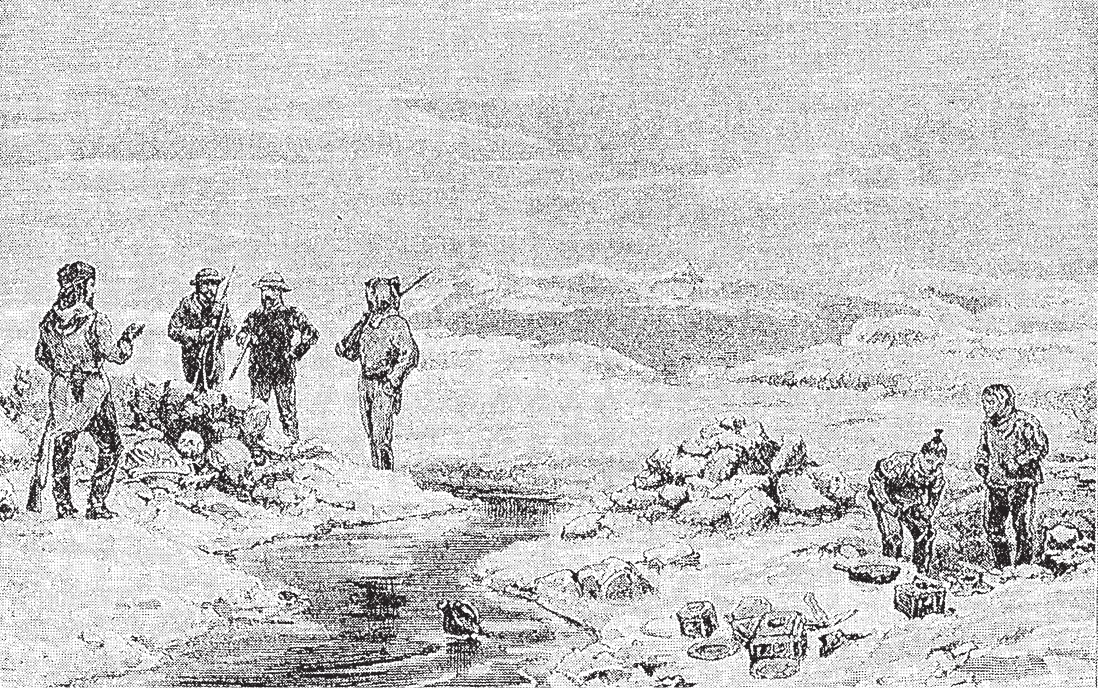

The Fox, trapped in Baffin Bay in 1857–58.

M’Clintock reached the mainland and continued southward to Montreal Island, where a few relics, including a piece of a preserved meat tin, two pieces of iron hoop and other scraps of metal, were found. The sledge party then turned back to King William Island, where they searched along its southern, then western coasts. Ghastly secrets awaited both M’Clintock and Hobson as they trudged over the snow-covered land.

Shortly after midnight on 24 May 1859, a human skeleton in the uniform of a steward from the lost expedition was found on a gravel ridge near the mouth of Peffer River on the island’s southern shore. M’Clintock recorded the tragic scene in his journal:

This poor man seems to have selected the bare ridge top, as affording the least tiresome walking, and to have fallen upon his face in the position in which we found him. It was a melancholy truth that the old woman spoke when she said, “they fell down and died as they walked along.”

M’Clintock believed the man had fallen asleep in this position and that his “last moments were undisturbed by suffering.”

Alongside the bleached skeleton lay a “a small clothes-brush near, and a horn pocket-comb, in which a few light-brown hairs still remained.” There was also a notebook, which belonged to Harry Peglar, captain of the foretop on the Terror. The notebook contained the handwriting of two individuals, Peglar and an unknown second. In the hand of Peglar was a song lyric, dated 21 April 1847, which begins: “The C the C the open C it grew so fresh the Ever free.” A mystery, however, surrounds the other papers, written in the hand of the unknown and referring to the disaster. Most of the words in the messages were spelled backwards and ended with capital letters, as if the end were the beginning. One sheet of paper had a crude drawing of an eye, with the words “lid Bay” underneath. When corrected, another message reads: “Oh Death whare is thy sting, the grave at Comfort Cove for who has any douat how… the dyer sad… ” On the other side of that paper, words were written in a circle, and inside the circle was the passage, “the terror camp clear.” This has been interpreted as a place name, a reference to a temporary encampment made by the Franklin expedition—possibly the encampment at Beechey Island. Another paper, written in the same hand, also spelled backwards, includes this passage: “Has we have got some very hard ground to heave… we shall want some grog to wet houer… issel… all my art Tom for I do think… time… I cloze should lay and… the 21st night a gread.” The “21st night” could be 21 April 1848, the eve of the desertion of the Erebus and Terror—a possibility raised because of another discovery. The most important artefact of the Franklin searches had been located three weeks before the skeleton was found, as Hobson surveyed the northwest coast of the island. On 5 May, the only written record of the Franklin expedition—chronicling some of the events after the desertion of the ships and consisting of two brief notes scrawled on a single piece of naval record paper—was found in a cairn near Victory Point. The first, signed by Lieutenant Graham Gore, outlined the progress of the expedition to May 1847:

28 of May 1847. HM Ships Erebus and Terror… Wintered in the Ice in Lat. 70˚ 05′ N. Long. 98˚ 23′ W. Having wintered in 1846–7 at Beechey Island in Lat. 74˚ 43′ 28″ N Long. 90˚ 39′ 15″ W after having ascended Wellington Channel to Lat. 77˚—and returned by the west side of Cornwallis Island. Sir John Franklin commanding the Expedition. All well. Party consisting of 2 officers and 6 Men left the Ships on Monday 24th. May 1847. Gm. Gore, Lieut. Chas. F. Des Voeux, mate.

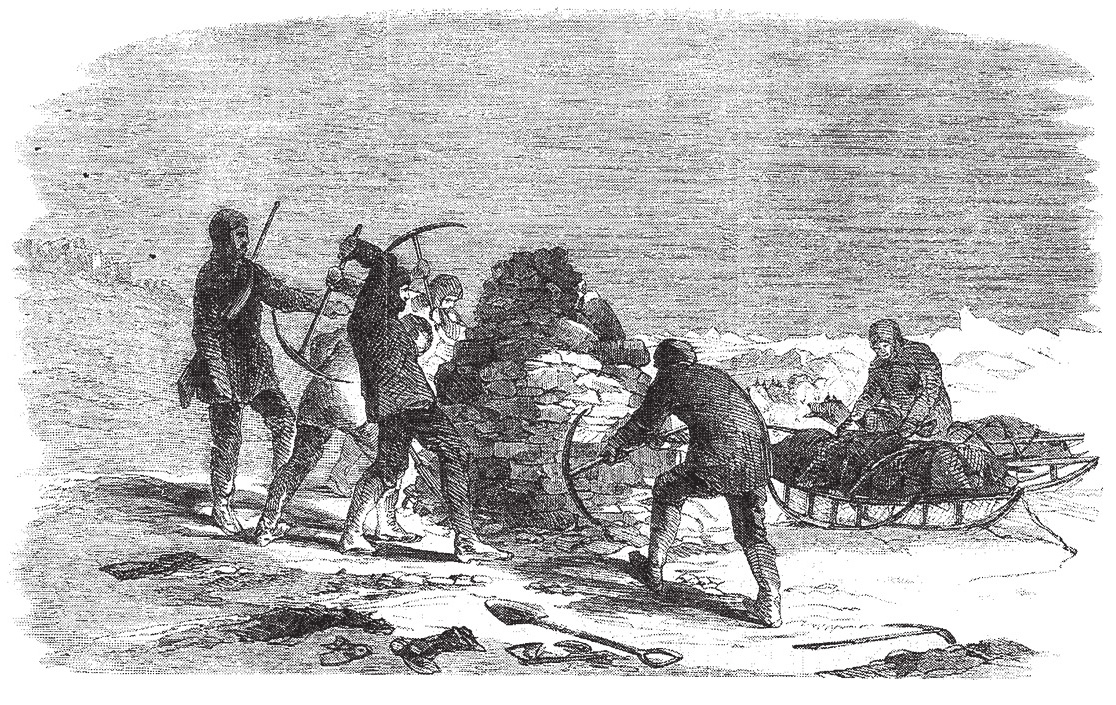

Lieutenant Hobson and his men opening the cairn— near Victory Point, King William Island—that contained the only written record of the Franklin expedition’s fate.

The document is notable for an inexplicable error in a date—the expedition had wintered at Beechey Island in 1845–46, not 1846–47—and its unequivocal proclamation: “All well.” Originally deposited in a metal canister under a stone cairn, the note was retrieved eleven months later and additional text then scribbled around its margins. It was this note that in its simplicity told of the disastrous conclusion to 129 lives:

(25th April) 1848—HM’s Ships Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April, 5 leagues NNW of this, having been beset since 12th Septr. 1846. The Officers and Crews, consisting of 105 souls, under the command of Captain F.R.M. Crozier landed here—in Lat. 69˚ 37′ 42″ Long. 98˚ 41′. This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831, 4 miles to the Northward, where it had been deposited by the late Commander Gore in June 1847. Sir James Ross’ pillar has not however been found, and the paper has been transferred to this position which is that in which Sir J Ross’ pillar was erected—Sir John Franklin died on 11th of June 1847 and the total loss by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 Officers and 15 Men.

James Fitzjames, Captain HMS Erebus.

F.R.M. Crozier Captain and Senior Offr.

and start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River.

The notes found in the cairn at Victory Point on 5 May 1859, by Lieutenant Hobson and his men.

“So sad a tale was never told in fewer words,” M’Clintock commented after examining the note. Indeed, everything had changed in the eleven months between the two messages. Beset by pack-ice since September 1846, Franklin’s two ships ought to have been freed during the brief summer of 1847, allowing them to continue their push to the western exit of the passage at Bering Strait. Instead, they remained frozen fast and had been forced to spend a second winter off King William Island. For the Franklin expedition, this was the death warrant. There had already been an astonishing mortality rate, especially among officers. Deserting their ships on 22 April 1848, the 105 surviving officers and men set up camp on the northwest coast of King William Island, preparing for a trek south to the mouth of the Back River, then an arduous ascent to a distant Hudson’s Bay Company post, Fort Resolution, which lay some 1,250 miles (2,210 km) away. M’Clintock described the scene where the note had been discovered:

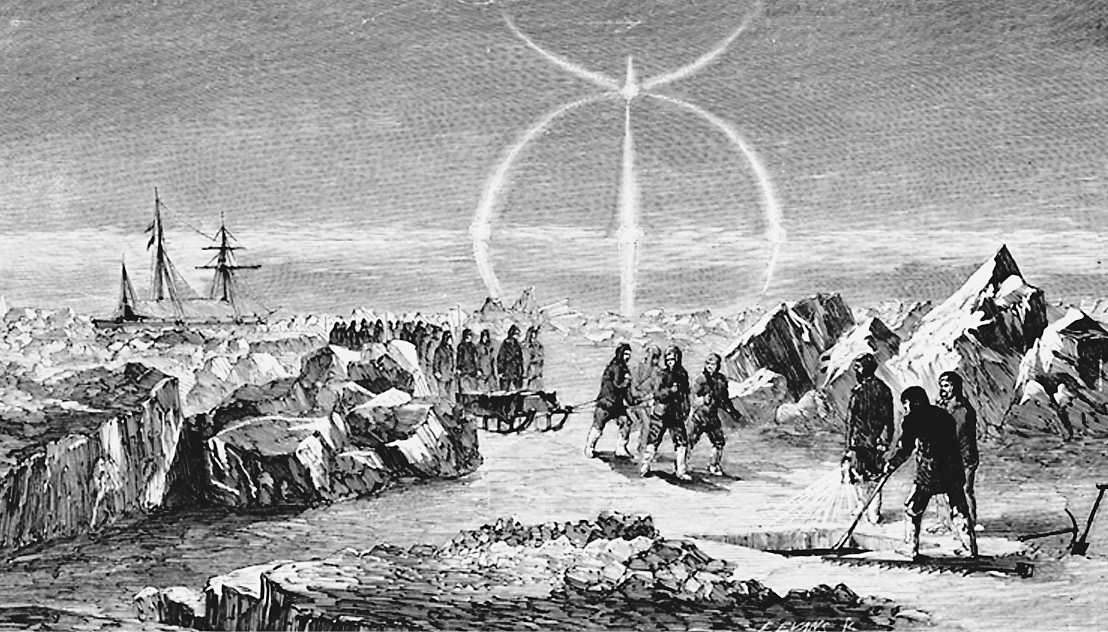

Around the cairn a vast quantity of clothing and stores of all sorts lay strewed about, as if at this spot every article was thrown away which could possibly be dispensed with—such as pickaxes, shovels, boats, cooking stoves, ironwork, rope, blocks, canvas, instruments, oars and medicine-chest.

Why some of these items had been carried even as far as Victory Point is another of the questions that cannot be answered, but M’Clintock was sure of one thing: “our doomed and scurvy-stricken countrymen calmly prepared themselves to struggle manfully for life.” The magnitude of the endeavour facing the crews must have been overwhelming, and the knowledge of its futility spiritually crushing. It also ran contrary to the best guesses of other leading Arctic explorers. George Back, who had explored the river named for him in 1834, was certain Franklin’s men would not have attempted an escape over the mainland: “I can say from experience that no toilworn and exhausted party could have the least chance of existence by going there.” John Rae thought that “Sir John Franklin would have followed the route taken by Sir John Ross in escaping from Regent Inlet.”

To this day, the route of the expedition retreat confounds some historians, who, like Rae, believe a much more logical and attainable goal would have been to march north and east to Somerset Island and Fury Beach—the route by which John Ross had made good an escape from an ice-bound ship in 1833. Fury Beach was not much further for the crews of the Erebus and the Terror than it had been for John Ross’s crew of the abandoned Victory. It was also the most obvious place for a relief expedition to be sent, and James Clark Ross did indeed reach the area with two ships, five months after the Erebus and Terror were deserted.

Instead, after quitting their camp on 26 April, the crews moved south along the coastline of King William Island, man-hauling heavily laden lifeboats that had been removed from the ships and mounted on large sledges. Plagued by their rapidly deteriorating health, the crews were then overcome by the physical demands of the task. M’Clintock found what appeared to have been a field hospital established by Franklin’s retreating crews only eighty miles into their trek. He suspected scurvy. Speculation also focussed on the tinned food supply. Inuit later told of some of their people eating the contents of the tins “and it had made them very ill: indeed some had actually died.” As for Franklin’s men, many died along the west and south coasts of King William Island.

Later, Hobson found a vivid indication of the tragedy when he located a lifeboat from the Franklin expedition containing skeletons and relics. Men from Franklin’s crews had at last been found, but the help had come a decade too late. When M’Clintock later visited the “boat place,” he described his tiny party as being “transfixed with awe” at the sight of the two human skeletons that lay inside the boat. One skeleton, found in the bow, had been partly destroyed by “large and powerful animals, probably wolves,” M’Clintock guessed. But the other skeleton remained untouched, “enveloped with cloths and furs,” feet tucked into warm boots to protect against the harsh Arctic cold. Nearby were two loaded double-barrelled guns, as if ready to fend off an attack that never came.

M’Clintock named the area, on the western extreme of King William Island, Cape Crozier. The boat, which had been carefully equipped for the ascent of the Back River, was 28 feet (8.5 metres) long; M’Clintock estimated the combined weight of the boat and the oak sledge it was mounted on at 1,400 pounds (635 kg).

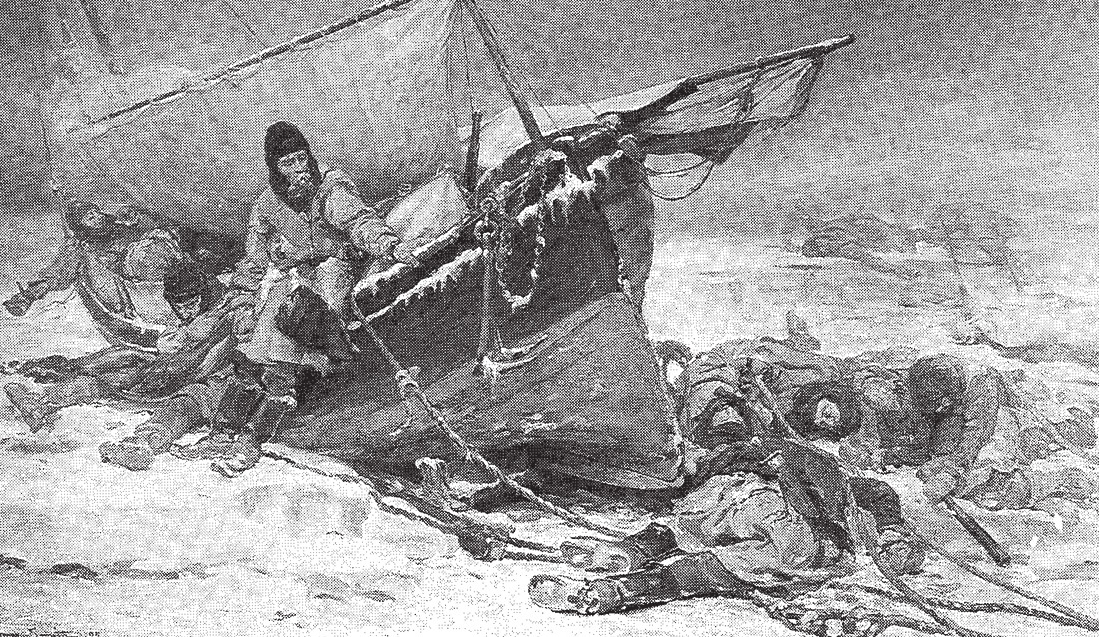

M’Clintock discovers a lifeboat—containing skeletons— from the Franklin expedition.

Careful lists of the “amazing” quantity of goods also contained in the boat were compiled. Everything from boots and silk handkerchiefs to curtain rods, silverware, scented soap, sponges, slippers, toothbrushes and hair-combs were found. Six books, including a Bible in which most of the verses were underlined, A Manual of Private Devotions and The Vicar of Wakefield, were also discovered and scoured for messages, but none were found. The only provisions in the boat were tea and chocolate. M’Clintock judged the astonishing variety of articles “a mere accumulation of dead weight, of little use, and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge-crews.” Perhaps strangest of all was the direction in which the boat was pointing, for instead of heading towards the river that was the target of the struggling survivors, the boat was pointed back towards the deserted ships. M’Clintock guessed that the party had broken off from the main body of men under the command of Crozier, and was making a failed attempt to return to the ships for food: “Whether it was the intention of this boat party to await the result of another season in the ships, or to follow the track of the main body to the Great Fish [Back] River, is now a matter of conjecture.”

This picture, of dying seamen shambling along, dragging sledges loaded down with the detritus of Victorian England, is the enduring image of the Franklin expedition disaster. Reviewing the evidence in 1881, M’Clintock concluded that surviving members of Franklin’s expedition:

… were far gone with scurvy when they landed; and the change from the confined lower decks, and inaction, to extreme exposure in an Arctic temperature, combined with intensely hard sledging labour, would almost immediately mature even incipient scurvy. The hospital tent within 80 miles [130 km] of the spot where their march commenced is, I think, conclusive proof of this. The Investigator [McClure’s search expedition] is almost the only ship which has ever similarly spent three winters in the ice. Although she had only three deaths in all that time, yet a careful medical examination revealed the fact that only 4 out of a total of 64 on board were not more or less affected by scurvy. Such is the usual results of limitation to salted or preserved provisions, unrelieved by fresh animal or vegetable food. It is evident that disease, not starvation, carried off the earliest and by far the largest number of Franklin’s companions, those martyrs to the cause of geographical discovery.

Even among his own sledging parties, M’Clintock observed, “scurvy advanced with rapid strides.” Hobson, who had carried tinned pemmican for food, “suffered very severely in health,” ultimately having to be dragged back on the sledge. Wrote M’Clintock of Hobson’s plight: “How strongly this bears upon the last sad march of [Franklin’s] lost crews!” Years later, Hobson was asked: “Can you give… any opinion as to the cause why scurvy broke out with you?” His answer was, “I can scarcely say that scurvy did break out with us. I said that the men were debilitated, that they lost stamina. There was no cause that I know of, except the fact of not being able to get really fresh meat and fresh vegetables.”

Franklin’s men lie dying beside the boat with which they had planned to ascend the Back River, King William Island. Oil painting by W.T. Smith

Burial in mid-winter, from M’Clintock’s voyage aboard the Fox.

The success of their voyage brought both honour and fame to M’Clintock and Hobson, as well as some solace to Lady Franklin. She now knew the exact date of Franklin’s death and that he had died aboard-ship long before the final, gruesome events on King William Island, thus preserving his reputation. What is more, he had died close enough to his objective to have justified at least a moral claim to the prize: Discoverer of the Northwest Passage. M’Clintock had produced, it was popularly decided, “melancholy evidence of their success.” Sherard Osborn, who had commanded a ship in an earlier search, captured the public mood when he wrote of Franklin:

Oh, mourn him not! unless you can point to a more honourable end or a nobler grave. Like another Moses, he fell when his work was accomplished, with the long object of his life in view.

The burial of Franklin. Depicted on the monument erected to him at Waterloo Place, London.

In Toronto, the Globe echoed:

Sir John, we now know, sleeps his last sleep by the shores of those icy seas whose barriers he in vain essayed to overcome. He died, as British seamen love to die, at the post of duty. Surrounded, let us hope, by his gallant officers, who, while he lived, would minister to his every want, and when dead would bear him to his cold and lonely tomb in some rocky bay, with saddened hearts and tear-bedewed eyes.

Finally, on 15 October 1859, the Illustrated London News attempted to recapture the emotions felt by Franklin’s sailors near Victory Point in their final desperate struggle to survive:

Awfully impressing must it have been to Lieutenant Hobson, and subsequently Captain M’Clintock, when they thus stood upon the intrenched scene where their gallant countrymen had, eleven years previously, prepared themselves for that last terrible struggle for life and home. Who shall tell how they struggled, how they hoped against hope, how the fainting few who reached Cape Herschel threw themselves on their knees and thanked their God that, if it so pleased Him that England and home should never be reached! He had granted to them the glory of securing to their dear country the honour they had sought for her—the discovery of the Northwest Passage.

In their last final march, the crews of the Erebus and Terror had indeed discovered the Northwest Passage. But by the time they walked along the shores of Simpson Strait, the triumph must have been a hollow one, for all around them was despair.

Franklin and his crews entered the Arctic with their primary goal the completion of the passage. Although geographically there is no single passage, and on a map it is possible to plot a myriad of routes around and through the clusters of islands that make up the Arctic archipelago, in reality, until the advent of ice-breakers, ice conditions narrowed the possibilities to only a few choices. By 1845, when Franklin sailed, much of the mainland coast of North America had been charted by overland explorers questing for a navigable passage, and when the ship-based explorations up to that point are added to the map of the Arctic, it becomes apparent that only a relatively short distance, in the King William Island region, remained uncharted.

In their first season in the Arctic, Franklin’s ships sailed up Wellington Channel to 77˚N latitude where they were turned back either by ice or the lateness of the season. The expedition then travelled south to Barrow Strait by a previously unexplored channel between Bathurst and Cornwallis islands. Wrote M’Clintock: “Seldom has such an amount of success been accorded to an Arctic navigator in a single season, and when the Erebus and Terror were secured at Beechey Island for the coming winter of 1845–46, the results of their first year’s labour must have been most cheering.” When the sailing season of 1846 began with the break-up of ice in Barrow Strait and in Erebus Bay (their winter harbour off Beechey Island), the two ships sailed roughly south and west, ending beset in the ice off the northwest coast of King William Island in September 1846. What route the ships took to reach this point is still a matter of conjecture, though it is likely the Erebus and Terror travelled through Peel Sound and what is now Franklin Strait between Somerset and Prince of Wales islands. Franklin believed this route would eventually lead him to parts of the mainland coastline he had explored two decades earlier. His maps told him that, in the King William Island area, he had to complete the stretch along the west side of what was then called King William’s Land (a distance M’Clintock estimated at 90 miles/145 km—but, in fact, was actually 62 miles/100 km) to be credited with completing the charting of a Northwest Passage.

The northern extent of this unknown gap was a low point of land on the northwest coast of King William Island, visited by James Clark Ross from the east in the late spring of 1830. Ross had named the location Victory Point. The southern extent was to be found at Cape John Herschel on the south coast of King William Island. In 1839, Peter Warren Dease and Thomas Simpson explored along the mainland coast; moving eastward along the coast to Boothia Peninsula, they eventually turned back to the south coast of King William Island, exploring the island until they reached Cape John Herschel, where they built a large cairn. From this point they crossed back to the mainland and retraced their route to the west, a route which itself had been extended over time to Bering Strait, the western entrance to the passage.

Curiously, perhaps tragically, both Ross in 1830 and Dease and Simpson in 1839 suggested that the area they had explored was an extension of the mainland—a bulge of land connected directly to the southwestern part of Boothia Peninsula. It is very likely that Franklin, armed with the maps, descriptions and opinions of these earlier explorers as well as his own theories on the geography of the region, believed he had no choice in sailing direction when he eventually encountered Cape Felix, the northern tip of King William Island. Thinking that a route to the east of this point would lead to a dead end, he turned his ships to the southwest, directly into the continuously replenished pack-ice that grinds down the length of McClintock Channel from the northwest. The power and persistence of this ploughing train of ice cannot be overestimated; the northwest coast of King William Island bears the scars as proof. This ice mass does not always clear during the short summers and a lethal trap awaited the two ships, a trap made all the more cruel with the realization that the route along the eastern coast of the island regularly clears during the summer. It was only during their final doomed march that the surviving men from the Erebus and Terror completed the gap—and the Northwest Passage. In the words of searcher Sir John Richardson, “they forged the last link of the Northwest Passage with their lives.”

M’Clintock’s discoveries on King William Island thus provided an outline of the expedition’s last days. And with this new information, the final clamour for answers to the Franklin mystery died down, even though it was apparent that many questions remained. As the Illustrated London News was to explain on 1 January 1881: “[M’Clintock’s] search was necessarily a hasty and partial one, as the snow lay thick on the ground, and the parties had to return to their vessel before the disruption of the ice in summer.”

In the end, the impetus for continuing to probe the Franklin disaster came not so much from the British but from two colourful Americans, who were without any Arctic experience when they each began their separate searches.

Charles Francis Hall.

Charles Francis Hall, a Cincinnati, Ohio, businessman who became interested in the Arctic following the disappearance of Franklin’s expedition, decided in 1859 to conduct a search of his own. Hall argued before potential backers that Franklin survivors might still be alive among the Inuit; besides, the shores of King William Island needed to be searched during the summer for more clues as to the expedition’s last days. After a failed first attempt to reach King William Island, Hall returned again in July 1864, finally reaching its southern coast in May 1869. Here, Hall noted Inuit accounts of cannibalism among Franklin’s starving crews. He also recorded his anger at learning from the Inuit that, while several native families had provided an officer thought to be Crozier and a group of his men with some seal meat, the Inuit had then left, ignoring pleas for further aid. Forgetting to add that the Inuit themselves only managed to survive at subsistence level, Hall wrote:

These 4 families could have saved Crozier’s life & that of his company had they been so disposed… But no, though noble Crozier pleaded with them, they would not stop even a day to try & catch seals—but early in the morning abandoned what they knew to be a large starving company of white men.

Hall itemized Franklin relics found in the possession of the Inuit, including a mahogany writing desk that “had been recently in use as a blubber-tray.” He transcribed Inuit testimony of having dug up, and left unburied, a body on King William Island: “This white man was very large and tall, and by state of gums and teeth was terribly sick.” The Inuit also recounted having seen a ship in the area of O’Reilly Island, off the Adelaide Peninsula, which Hall took to be evidence that either the Erebus or Terror had “consummated the Great Northwest Passage.” According to their account, the Inuit had at first approached the ship with caution, but when it seemed no one was aboard, a group visited it. In a locked cabin, they told of the discovery of “a dead man, whose body was very large and heavy, his teeth long. It took five men to lift this giant kob-lu-na. He was left where they found him.” According to Hall’s intelligence, the Inuit then began “ransacking” the ship for materials. Among the many items on board, they described seeing meat in cans.

Hall deduced that the Inuit found the ship in the spring of 1849. According to the Inuit account, there was a gangway reaching from the deck to the ice, suggesting that the vessel was still occupied that winter. The ship sank a short time later and debris, masts, boxes and casks drifted to shore. It was after this that an intriguing discovery was made: “fresh tracks were seen of four men and a dog on the land where the ship was. In-nook-poo-zhee-jook, who had seen Ross and his party on the Victory and Rae in 1854, knew these tracks to be kob-lu-nas’… ” If that is the case, then it is likely that survivors of the Franklin expedition were alive at the time that James Clark Ross made his sledge journey in May 1849.

Searching for remains on King William Island and on nearby islets, Hall in once instance identified a human thigh bone, but his work was constrained because snow remained on the ground. He also found a skeleton, later identified by a gold filling as Lieutenant Henry Le Vesconte of the Erebus. Hall conducted a solemn ceremony to honour the dead man, including flying the American flag at half-mast and building a monument of stones. The remains were then collected by Hall and taken to the United States before being returned to England, where they were entombed at a Franklin memorial in Greenwich Hospital.

Much more important American discoveries were to come. On 19 June 1878, Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka, a United States cavalry officer who had served in the Indian wars of the American West at the same time as the famed defeat of Lieutenant Colonel George Custer at Little Big Horn, and who was also a qualified lawyer and medical doctor, led a tiny expedition backed by the American Geographical Society into the Arctic. Schwatka was inspired by Hall’s earlier efforts, and by American whalers who, having spoken with the Inuit, reported that documents of the lost expedition might be found.

Travelling by sledge on what was to become a 3,249-mile (5,232-km) return journey, Schwatka was able to reach King William Island and conduct a thorough search in 1878–79 along the route taken during the retreat of the Erebus and Terror crews. Besides confirming important aspects of M’Clintock’s search, Schwatka added immeasurably to the record of relics and human remains scattered along the western and southern coasts of the island.

On 21 July 1879, Schwatka visited the boat place seen by M’Clintock some nineteen years earlier, but instead of an intact boat and contents, he found that the site had “evidently been thoroughly overhauled by the natives.” Besides the remnants of the boat, Schwatka found combs, sponges, toothbrushes, bottles and powder cans. He also found the widely distributed bones of four skeletons, including three skulls.

On 24 June that same summer, at what Schwatka called the “very crest” of his long journey, near Victory Point on the island’s northwest shores, an opened grave was discovered. A medal with the name of John Irving engraved on it was found at the site, though the grave had been “despoiled by the natives some years before.” Schwatka described the scene in his journal:

In the grave was found the object-glass of a marine telescope, and a few officer’s gilt-buttons stamped with an anchor and surrounded by a crown. Under the head was a colored silk handkerchief, still in a fair state of preservation, and many pieces of coarsely stitched canvas, showing that this had been used as a receptacle for the body when interred.

Because of the original care taken in the burial, Schwatka believed that the body had been buried from the ships, where a proper coffin could have been constructed. The gravesite stood in contrast to the final resting places of the other Franklin sailors found on King William Island, where the bones lay scattered on the ground. A human skull and other bones, thought to be Irving’s, were found scattered over a wide area around the grave. “They were carefully gathered together, with a few pieces of cloth and other articles, to be brought home for interment where they may hereafter rest undisturbed,” Schwatka wrote. (Of all the skeletal remains discovered by the American, only those identified as belonging to Irving were removed from the island, to be eventually buried with full naval honours at Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh.)

The grave of Lieutenant John Irving, and relics from the HMS Terror, found by Lieutenant Schwatka.

Schwatka’s expedition made other discoveries: a large cairn covering a fragment of paper with a hand drawn on it, the index finger pointing; an Inuit cache with more relics, including several red cans marked “Goldner’s Patent.” Schwatka also found and interviewed a woman who said that some of the men she had met had “dry and hard and black” mouths, suggesting the presence of scurvy. He also recorded testimony similar to that collected by Hall, from an old man named Ikinnelikpatolok, who told of a large ship frozen in the ice to the west of Adelaide Peninsula, north of O’Reilly Island, and claimed he had seen one white man “dead in a bunk.” Among other items, “they found some red cans of fresh meat, with plenty of what looked like tallow mixed with it. A great many had been opened, and four were still unopened.”

Before leaving the Arctic, Schwatka met an old Inuk woman and her son who told a grim story of finding relics of the Franklin expedition on the shores of the North American mainland many years before, including one of the lifeboats the retreating crewmen had been dragging. Schwatka recorded the son’s account:

Outside the boat he saw a number of skulls. He forgot how many, but said there were more than four. He also saw bones from legs and arms that appeared to have been sawed off. Inside the boat was a box filled with bones; the box was about the same size as… one with the books in it.

The last thirty or forty of Franklin’s men had apparently left the tragedy of King William Island behind them near the mouth of the Peffer River and crossed Simpson Strait, only to exhaust their last hopes in the barren reaches of an area Schwatka named Starvation Cove. (It has been argued that the two boxes may have contained the remains of Sir John Franklin and the expedition logs, but they have been lost forever.) A search of the area revealed little, only the partial remains of one sailor. The Inuit explained that the land had reclaimed the rest of the bodies—that the bones had sunk into the sand, mute testimony of the horror that visited the area so long ago.

Schwatka’s party returned to the United States in September 1880. The Illustrated London News provided detailed coverage of the expedition’s journey across King William Island, including an explanation for the absence of proper graves:

The coast had evidently been frequently visited by natives, who had disinterred those who had been buried for the sake of plunder, and left their remains to the ravages of the wild beasts… [Schwatka’s party] buried the bones of all those unfortunates remaining above ground and erected monuments to their memory. Their research has established the fact that the records of Franklin’s expedition are lost beyond recovery.

The president of the Royal Geographical Society concluded that the Franklin search expeditions had succeeded in surveying much of the Arctic archipelago and “expunged the blot of obscurity which would otherwise have hung over and disfigured the history of this enlightened age.” Despite the failure to locate the ships’ records, or either of the two vessels, the Franklin searches had also pierced the Arctic long enough to answer the fundamental mysteries of the expedition’s disappearance. Its route had been generally established, the reason for the desertion of the Erebus and Terror was made known and the Inuit accounts and sad discovery of relics on King William Island attested to the crews’ final chilling days of life.

With the great search at last over, Tennyson wrote the epitaph for the Westminster Abbey memorial to Franklin:

Not here: the white North hath thy bones, and thou

Heroic Sailor Soul

Art passing on thy happier voyage now

Toward no earthly pole

Britain transferred sovereignty of the Arctic islands to Canada in 1880. The Northwest Passage was finally sailed by Norway’s Roald Amundsen in 1903–06, aboard a wooden sloop named Gjoa. It was perhaps fitting that Amundsen should have been the first, for it was the narrative of Franklin’s 1819 overland journey that led him to dream of being a polar explorer. “Oddly enough it was the sufferings that Sir John and his men had to go through which attracted me most in his narrative. A strange urge made me wish that I too would go through the same thing,” wrote Amundsen, who conquered the passage and later the South Pole, only to die in a plane crash in Arctic waters in 1928. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Sergeant Henry Asbjorn Larsen later sailed the passage from west to east aboard the St. Roch in 1940–42, and from east to west in 1944.

Occasionally, bones thought to belong to a Franklin expedition member were discovered. In one case, a partial skeleton was sent to Canada’s National Museum in Ottawa, where it remains in storage. And in 1923, the explorer Knud Rasmussen, a native of Greenland, reported interring some remains on the east coast of the Adelaide Peninsula, which, from surviving scraps of clothing and footwear, were “unquestionably the last mortal remains of Franklin’s men.”

Rasmussen also wrote down Inuit oral history of the discovery of a deserted ship, found when the natives were hunting seals off the northwest coast of King William Island. One old man named Qaqortingneq described what was seen by those who went aboard: “At first they were afraid to go down into the lower part of the ship, but after a while they grew bolder, and ventured also into the houses underneath. Here they found many dead men, lying in the sleeping places there; all dead.”

Major L.T. Burwash of Canada’s Department of the Interior made several visits to King William Island, interviewing Inuit elders for further clues about the Franklin expedition. In April 1929 he secured a statement from two men named Enukshakak and Nowya who told of finding, forty years earlier, a large cache of wooden cases carrying “tin containers, some of which were painted red.” According to the men’s account, some of these provisions were tins of preserved meat, purportedly found on a low flat island to the east of King William Island. They expressed their belief that the cache was left by the crew of a ship that had been wrecked off nearby Matty Island. This testimony, coupled with the report, recorded by Schwatka, of a wreck a short distance from O’Reilly Island, prompted Burwash to present the theory that some of Franklin’s crews had returned to the Erebus and Terror and that “the ships were eventually brought to their final resting places while more or less under the control of their crews.”

Burwash also included with his account what was purported to be unpublished testimony from a member of Charles Francis Hall’s expedition, by then deceased, which strangely never made it into Hall’s official account. Attributed to an Inuk hunter, this additional material revealed that Sir John Franklin may have been buried in a cement vault on King William Island: “one man died on the ships and was brought ashore and buried… in an opening in the rock, and his body covered over with something that ‘after a while was all same stone.’ ” At the time the remains were interred, “many guns were fired.”

In 1930, Burwash and pilot W.E. Gilbert would become the first men to fly to Crozier’s Landing. However, there was little more than some rope and broadcloth left for them to see. Gilbert described the scene in an article published in the Edmonton Journal on 9 September 1930:

Bitter winds across the still snow-covered ground made work difficult and the ravages of the tremendous storms encountered here had largely obliterated the remains of the camps in the eighty years which had elapsed.

There was no sustained challenge to Franklin’s reputation mounted in Victorian times. It was not until 1939 that Canadian Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson wrote his essay, “The Lost Franklin Expedition,” and asked how these sea-toughened men, armed with shotguns and muskets, could have “contrived to die to the last man” of hunger so quickly in a land where the Inuit had survived for generations, hunting with Stone Age weapons.

Stefansson concluded that the chief failure of the Franklin expedition, and other nineteenth-century British explorers of the Arctic, was in the refusal to respond to the harsh environment by adopting the ways of the Inuit: “The main cause… was cultural.” An explorer and ethnographer, and a man who had subsisted on a fresh meat-only diet in the Arctic for seven years, Stefansson repeatedly argued that the Arctic explorers would have thrived had they done the same. As he wrote: “The strongest antiscorbutic qualities reside in certain fresh foods and diminish or disappear with storage by any of the common methods of preservation—canning, pickling, drying, etc.” Yet as late as 1928, Stefansson’s theories about the antiscorbutic value of fresh meat continued to be greeted with skepticism. As a result, he submitted to a bizarre experiment in which he ate nothing but raw meat for a year while living in New York City. To the astonishment of medical observers, he remained perfectly healthy.

There is no doubt that an abundance of fresh meat would have offered a means of salvation to Franklin expedition survivors. As Stefansson argued, Franklin and his officers need only have studied the narratives of two then recent expeditions to have had a command of the situation: “When you compare the John Ross expedition of 1829–33 with the George Back expedition of 1836–37, you have the complete answer to how a polar residence should be managed.” Stefansson conceded, however, that while John Ross had wisely adopted the Inuit diet, he had not demonstrated that whites could be adequately self-supporting, as most of the food had been obtained from the Inuit through barter. In addition, there is evidence that Franklin expedition survivors did procure limited amounts of fresh meat from the Inuit, but pleas for further aid were then rebuffed.

In truth, the large number of survivors disgorged onto King William Island doomed any hopes of securing adequate quantities of fresh meat. Even among the Inuit, episodes of starvation have been documented in the region of King William Island and the adjacent mainland. Schwatka encountered Inuit who he reported were “in great distress for food” and who had already lost one of their number to starvation. He gave them caribou meat. Knud Rasmussen also wrote that, for the Inuit, life is “an almost uninterrupted struggle for bare existence, and periods of dearth and actual starvation are not infrequent.” As late as 1920, Rasmussen documented that eighteen Inuit had died of starvation at Simpson Strait.

More to the point, Stefansson noted the curiously high number of deaths—before the Erebus and Terror were deserted, “while there were still large quantities of food on the ships.” That “scurvy took so heavy a toll” even then, required, he argued, a “special explanation.” If scurvy was indeed the cause of those deaths, then that explanation was almost certainly an enduring faith in the antiscorbutic value of tinned foods. As the historian Richard J. Cyriax stated in his 1939 study of the Franklin expedition: “As tinned preserved meat has no antiscorbutic properties, Goldner’s meat, if perfectly good, would not have prevented scurvy.”