9. The Boat Place

In surveying the King William Island coastline the following year, Beattie, this time with field assistants Walt Kowal, a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Alberta, Arne Carlson, an archaeology and geography graduate from Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and Inuk student Arsien Tungilik, planned to retrace the searches of M’Clintock in 1859 and Schwatka in 1878–79.

Although both nineteenth-century searchers had discovered the skeletal remains of crewmen at a number of sites, the surveyors would concentrate on Schwatka’s published accounts, since the explorer had found and described more of these finds. Schwatka had also gathered up the scattered bones and buried them in common graves at the various sites, placing stone markers on them. Beattie hoped these graves could be located, and, with great anticipation, plotted their supposed position using Schwatka’s journals and maps. From the descriptions of bones buried at some of the sites, the number of crewmen represented could be four or more.

After a three-and-a-half-hour flight south from Resolute on 28 June 1982, the Twin Otter supplied by the Polar Continental Shelf Project swept over Seal Bay on the west coast of King William Island. Spotting a dry gravel ridge near the beach, the pilot circled back, flying close to the ground and as slow as aerodynamics would allow. The co-pilot opened a door and, with the help of Arne Carlson, booted a crate filled with supplies out of the plane. All watched as the box bounced a few times and rolled to a stop on the ridge, its pink-coloured cloth wrapping visible from miles away. The aircraft then headed south along the coast to Erebus Bay, where a similar procedure took place. (The run-off from melting snow on King William Island made landings too risky that season, and the staff at the Polar Shelf base in Resolute came up with the idea of the air drops.)

The scientific team then headed on to Gjoa Haven, where field assistant Arsien Tungilik was picked up. The Twin Otter soon flew back towards the northwest coast. After a time, the pilot suddenly banked the plane to the left—he had spotted a potentially good landing site in a land otherwise covered with summer run-off. Gesturing to Beattie, he pointed out of his window to the beach ridge and nodded his head. Looking at his map, then out the window, Beattie nodded back that the site, about 3 miles (5 km) north of Victory Point, would make a good starting point for the survey. After making one more low-level pass, the pilot put the plane down with feet to spare and, with one engine left running, the scientific crew jumped out of the plane’s side door and began unloading their supplies. Within five minutes everything was piled outside, and the pilot and his co-pilot pulled themselves back up into the plane. After restarting the second engine and throttling up, the plane edged forward. Seconds later it was airborne and heading north, then immediately it banked and flew past the group on the ground, the pilots waving as they set course for distant Gjoa Haven to refuel before their return to Resolute.

Although the team’s food caches had been dropped along their planned route, each person’s backpack was weighed down with food and supplies. Extra clothing for temperatures expected to hover around the freezing point, and other personal items, were usually stuffed to the bottom. Next came the food, consisting mainly of packaged freeze-dried goods and chocolate bars. Other important items such as matches, tent- and boot-repair kits, first-aid kits and ammunition were packed near the top. Sleeping bags were tied to the bottom of the packs, with a tent and sleeping pad strapped one to each side. The rifle and shotgun were attached to the top and could be reached easily while the pack was on. Other items that increased the weight of each load were the cooking utensils, stoves and fuel. A radio was carried, with which they would make twice-daily contact with the base camp at Resolute. Later, when leaving a cache site, their packs would be stuffed to overflowing with supplies and more things would be hanging from straps on the outside.

Each team member was burdened with one of these heavy packs (Beattie and Tungilik carried more than 60 pounds/30 kg; Carlson carried even more), but it was Kowal, a powerful man with seemingly endless energy, who served as the self-assigned workhorse for the survey party. During the first phase of the fieldwork, Beattie and Carlson had to lift Kowal’s pack up to help him get it on. In it, in addition to his own belongings, he carried food, the radio, a rifle, ammunition, a sleeping bag and pad, a tent, an inflatable raft, a set of oars, two camp stoves, his camera and, strapped to the back of the pack, a full 5-gallon (23-litre) container of stove fuel—for a total weight of more than 130 pounds (60 kg). Beattie was amused and amazed at the sight of Kowal as they moved along on their survey: a huge mountain of supplies appeared to be lumbering ahead on its own, powered by two legs that would disappear as Kowal squatted to investigate something on the ground. The mountain would then slowly rise and continue along on its course.

Loaded down as they were, each researcher had to move slowly to conserve energy. The survey needed alert minds and inquisitive eyes; fatigue would steal those necessary qualities away. They took frequent rests supplemented by liquids (tea, coffee, hot chocolate) between each camp. Even with these breaks, they were able to survey between 6 and 12 miles (10 and 20 km) each day, and when searching an area out of one of their established camps, they took only the necessary supplies for one day, greatly increasing their range and speed.

Their first day on the island, even before they had a chance to set up camp, a curious Arctic fox was noticed studying them from a nearby beach ridge. Beattie thought of the brief visit by the small animal, still covered in its heavy white winter fur, as a form of welcome to the strange and exotic island they were about to explore. Although Beattie had visited King William Island’s south coast the previous year, he was about to survey areas where people had not been for many years.

When the fox had scurried off into the distance, the four surveyors busied themselves setting up the tents of their first camp and preparing a meal of freeze-dried food. After settling in, despite being tired from the long plane journey, they then briefly explored the surrounding area. Walking inland soon brought them to a large lake, and they could see in every direction that the land was flat and virtually covered in a sheet of water.

The following morning, as they moved northward along the coast, the temperature gradually warmed to 41˚F (5˚C), the sun emerged and the wind shifted so that it was blowing off the island. The team stopped briefly to remove parkas, then continued in shirt sleeves for the remainder of the day. The warmth of the season resulted in great quantities of meltwater flowing towards the coast from inland lakes, which made surveying conditions very difficult and almost impossible along parts of the route. Each mile of coastline covered usually required two or more miles of walking. Although their plan was to survey completely up the coast to Cape Felix, on the northwestern tip of the island, it would be physically impossible on foot. So when they reached a swiftly flowing stream at Cape Maria Louisa, 12 miles (20 km) south of Cape Felix, they decided to turn south. After searching unsuccessfully for a Franklin campsite that had been discovered in the area by M’Clintock and Hobson in 1859, they then camped for the night, returning to near Victory Point the next day.

Breaking camp on the morning of 30 June, the four men carried their supplies southward to the bank of another swollen stream. The depth of the water and speed of the current were too great to consider wading across, and they had to skirt round the outflow by walking out onto the ice of Victoria Strait. They wrapped their supplies in a large orange tarpaulin, tying the corners together. Then, dragging this large bundle and burdened with their overstuffed backpacks, they picked their way over the broken piles of ice at the waterline and out onto the smoother ice further offshore.

For the next two hours they walked, waded and jumped over fractures and cracks in the ice and areas of open water created by the stream, until they were able to angle back to the safety of the shore on the far side of the stream. After kicking off their boots and taking a well-earned rest, the survey then continued south along the shoreline to the place visited by James Clark Ross in 1830, subsequently named Victory Point.

Standing on the low rise of the point and looking south, Beattie was astonished by the accuracy of the scene, as depicted in an engraving made from a sketch drawn by Ross during his explorations—part of his uncle Captain John Ross’s failed 1829–33 expedition. James Clark Ross described his visit:

On Victory point we erected a cairn of stones six feet high, and we enclosed in it a canister containing a brief account of the proceedings of the expedition since its departure from England… though I must say that we did not entertain the most remote hope that our little history would ever meet an European’s eye.

Despite the accuracy of the engraving, nothing could be found of the cairn erected by Ross. Only a small cairn dating from the mid-1970s remained.

Victory Point is a low gravel projection into Victoria Strait, rising less than 33 feet (10 metres) above the high-water mark. From this spot it is possible to see Cape Jane Franklin several miles to the south, glazed with a permanent snow cover on its western rise, and to the west, the thin, horizontal dark line of Franklin Point. Ross named these features in 1830, in the case of Franklin Point writing in his journal that “if that be a name which has now been conferred on more places than one, these honours… are beyond all thought less than the merits of that officer deserve.” (In one of those instances of tragic irony, Sir John Franklin would die within sight of Franklin Point and Cape Jane Franklin, seventeen years later.)

Two miles (3 km) south of Victory Point, Beattie and his small party came across another, much smaller, projection of land, marking the site where the crews of the Erebus and Terror congregated on 25 April 1848, three days after deserting the ships 15 miles (24 km) to the NNW. It is this place that, along with Beechey Island, forms the focal point for the discovery of the fate of the expedition, for a note of immeasurable importance was left here, providing some of the few concrete details relating to the state and action of the crews from the wintering at Beechey Island in 1845–46 to the desertion of the ships on 22 April 1848.

Setting up camp, Beattie prepared to spend two days thoroughly researching and mapping the site as well as surveying the surrounding area. The two tents were placed so that their doorways faced each other; the team could then sit and prepare meals and talk in their own makeshift courtyard. During that first evening, the sky and clouds to the south darkened to a deep purple and bolts of lightning flashed out from the clouds, reaching down towards the ground. Although orange sunlight still shone on their camp, the four watched with anxiety as the dark storm moved westward to the south of them. The site, known as Crozier’s Landing, was so flat that their metal tent poles were prominent features—perhaps even lightning rods. They were relieved when the storm at last faded from view.

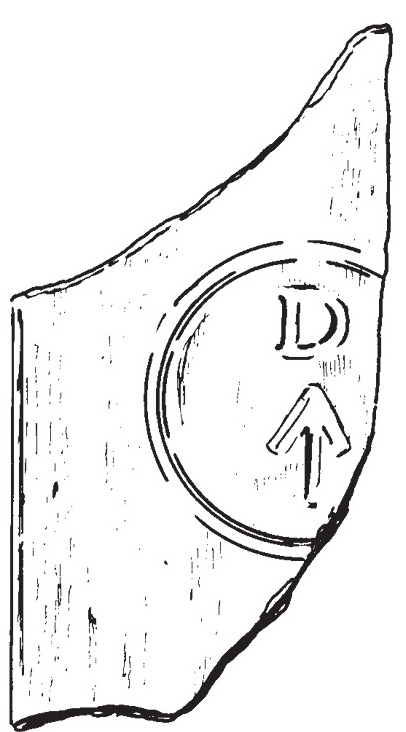

By 1982, few relics of the Franklin expedition remained at Crozier’s Landing. Where piles of the crews’ discarded belongings once lay strewn about, only scattered boot and clothing parts, wood fragments, canvas pieces, earthenware container fragments and other artefacts could now be gleaned from among the rocks and gravel. One rusted but complete iron belt buckle was found during the survey, as was a stove lid, near the spot where M’Clintock had located a stove and pile of coal from the expedition. A smashed but complete amber-coloured medicine bottle was also found, as was part of the body of a clear glass bottle, complete with navy broadarrow marking.

Glass fragment showing the navy broadarrow.

What struck Beattie was the paucity of the remains marking this major archaeological site. How could a place with such a history of tragedy and despair—shared by 105 doomed souls—appear so impartial to the events that transpired here during late April 1848? The artefacts that were mapped and collected in 1982 were pathetic, insignificant reminders of the failed expedition. Disturbances at the site were such that a search for the grave of Lieutenant John Irving, discovered by Schwatka, failed to turn up anything, though a series of at least thirteen stone circles indicated the actual location of the tenting site established by Franklin’s men. Other tent circles attested to the visits by searchers, primarily M’Clintock and Hobson in 1859 and Schwatka in 1879, and by Inuit. Evidence of more recent visits were also clearly visible: a hole excavated by L.T. Burwash in 1930, small piles of corroded metal fragments (possibly the remains of tin canisters), a note left by a group during an aerial visit made in August 1954 and other signs of visits made within the last decade. A modern cairn is situated at the highest point of the site, representing the approximate location of the cairn in which the note was discovered by Hobson in 1859.

However, Beattie’s group did make one interesting discovery as they marked with red survey tape the locations of artefacts scattered along the beach ridge. Paralleling this ridge, and towards the ice offshore, was an area of mud that, because of the time of year, had begun to thaw—and visible in the mud were coils of rope of various sizes. The anaerobic conditions of the mud and the long period of freezing each year had resulted in good preservation of the organic material, in stark contrast to the disintegrated rope and canvas fragments found on the gravel surface. One of the preserved coils was of a very heavy rope, about 2 inches (5 cm) in diameter. Yet despite this discovery, so little of the presence of Franklin’s men at Crozier’s Landing remained that it was almost impossible to visualize that scene of bustling activity and preparation that would have been played out in growing despair. The last marks of this most famous of Arctic expeditions were all but erased, as if scoured away by the constant, turbulent and chilling winds that blow off the ice. Beattie began to entertain the possibility that pursuing new leads into the fate of the expedition on King William Island might be a waste of time.

From the perspective gained at Crozier’s Landing, where the final agony of the explorers began in 1848, perhaps the deeper mystery was not so much the fate of the 105 men who died trying to walk out of the Arctic (which had until this time been Beattie’s focus), but the mystery of the twenty-four others who died (including a disproportionate number of officers) while the expedition was still aboard-ship and food stores remained. (After deserting their ships, the deaths of the 105 survivors seemed unavoidable along the desolate shores of King William Island.) To Beattie, it became increasingly obvious that the real Franklin mystery lay not here at its tragic end, but much earlier: the period from August 1845, when the expedition sailed into the Arctic archipelago, until 22 April 1848, when the ice-locked vessels were deserted off King William Island. For it was during those thirty-two lost months that nine officers, including Sir John Franklin, and fifteen seamen died. (Three were buried at Beechey Island; the graves of the others have never been found.)

Even before the ships were deserted, the Franklin expedition had been an unprecedented disaster. Its heavy losses contrasted sharply with the escape of John Ross and his crew, including James Clark Ross, after they deserted the discovery ship Victory on the southeast shore of the Boothia Peninsula in the early 1830s. For despite all that time in the Arctic, away from the protection of their ship and suffering the ravages of scurvy, Ross returned to England with nineteen of his twenty-two men. To Beattie, it began to appear that the most important insights into the Franklin disaster would come from the group of twenty-four who died aboard ship.

While Beattie and Carlson mapped and collected the few artefacts found at Crozier’s Landing, Kowal and Tungilik built a makeshift sledge from scraps of lumber found beside the ice edge. Round nails and the relatively fresh appearance of the wood suggested it was of very recent origin, and the two carpenters, using rocks for hammers, put it to good use. They planned to haul the camp supplies, mounted on the sledge, south across ice-covered Collinson Inlet to near Gore Point. Although the ice was fairly rotten and beginning to break, they calculated that, with some care, they could save more than a week’s walking by cutting across the inlet’s mouth instead of going round its wet and marshy source.

Carrying survey supplies out onto the ice of Victoria Strait.

Carrying survey supplies out onto the ice over Collinson Inlet, this time using a sledge made from twentieth-century timber and nails found at Crozier’s Landing.

Within an hour the sledge was complete and they prepared to resume their southward trek. The early evening hours were becoming cool and a silvery fog hung over the ice. The wind, usually a constant companion, had dropped to a whisper. Beattie and Carlson, who stayed behind to complete the artefact collection, watched as the other two were soon engulfed by the swirling fog. They stood silently for a few moments, listening to the receding sounds of trudging footsteps and the rasp of the sledge runners.

With Kowal pulling the sledge by a rope looped around his chest, the two weaved, struggled and fought their way across the 2.5-mile (4-km) distance in four hours. Tungilik, with his superior knowledge of ice conditions, walked ahead and scouted the safest route, which Kowal followed faithfully. When they reached land they lugged the supplies up onto the beach. Although both were completely exhausted, they immediately began the arduous journey back to rendezvous with Beattie and Carlson, who had struck out across the inlet after their artefact collection was completed.

The ice was very difficult and dangerous to cross. Parts were so soft that the men would sink to their knees; large ponds of melted water blanketed the ice surface. Wide cracks were a hazard in a number of locations and innumerable smaller cracks braided the ice. Tall, massive hummocks of snow and ice dotted the route, and Beattie worried about surprising a bear hidden on the opposite side of one of these—a healthy paranoia that resulted in a wide berth being given to these small ice mountains. As well, he noted that the ice they travelled over, and had seen offshore since their arrival on King William Island, was first-year ice, often little more than 12 inches (30 cm) thick. Recently, he knew, Polar Continental Shelf Project scientists had used ice core samples taken from High Arctic ice caps to study climate conditions over time, and had concluded that the Franklin era was climatically one of the least favourable periods in 700 years. This explained the multiyear ice encountered by Franklin off the northwest coast of King William Island, ice that was sometimes more than 80 inches (200 cm) thick.

Carrying packs filled with artefacts, Beattie and Carlson laboured across the ice for an hour. The fog had finally lifted when they saw Kowal and Tungilik a mile distant, heading towards them. Within another hour they were all safely across.

On 4 July, the team searched unsuccessfully for the grave of a Franklin crewman recorded by Schwatka. They also searched for the cairn at Gore Point, where a second Franklin expedition note was discovered by Hobson in 1859. (Virtually identical to the note found at Crozier’s Landing, this scrap of paper contained only information on the 1847 survey party of Gore and De Vouex. There were no marginal notes on the document, though, curiously, the error in the dates for wintering at Beechey Island was repeated.) A small pile of stones was located on the far end of Gore Point. As the pile was definitely of human origin and did not come from an old tenting structure (either Inuit or European), it seemed likely that the stones represented the dismantled cairn that had once held the note.

Moving southward along the coastline, the team encountered nothing to indicate that the area had been visited recently, only locations marking the probable campsites of Schwatka and his group. The next focal point in their survey was the supply cache that had been dropped from the air on the south shore of Seal Bay. After spending two days at this location, making good use of the stores of food and observing the dozens of seals that dotted the ice floes offshore, the team surveyed the coast down to a location adjacent to Point Le Vesconte, where Schwatka discovered and buried a human skeleton. Point Le Vesconte is a long, thin projection of land that is actually a series of islets. At low tide it is easy to walk out along the point, but, as the team discovered, at high tide the depth of water separating the islets can nearly reach the waist.

Of all of Schwatka’s descriptions, the locations of two skeletons along this coast were the best documented and most accurately identified on the survey team’s maps. At Point Le Vesconte, Schwatka had recorded human bones, including skull fragments scattered around a shallow grave that contained fine quality navy-blue cloth and gilt buttons. The incomplete skeleton, of what Schwatka believed had been an officer, had been carefully gathered together and reburied in its old grave and a stone monument constructed to mark the spot. Yet again, the survey team failed to locate this grave or the second one on the adjacent coastline. Beattie was disappointed. In “curating” the skeletal remains he discovered, Schwatka had apparently marked each grave with “monuments” consisting of just a couple of stones. Along King William Island’s gravel- and rock-covered coastline, such graves were lost in the landscape. After scouring the area for an entire day, the frustrated party pushed on to the south.

On the morning of 9 July, Beattie turned on his shortwave radio for the daily 7 AM radio contact with Resolute. But instead of being greeted by the reassuring and familiar voice from the Polar Shelf base camp, only a vacant hissing sound was heard. No contact with Resolute could be made that morning. The aerial was checked, the batteries changed, the radio connections and battery compartment cleaned, all in preparation for the regular evening communication.

Loss of radio contact is serious in the field; within forty-eight hours the Polar Shelf will dispatch a plane to the last known location of the party, bringing an extra radio and batteries. There may be a genuine emergency, but if the reason for missing radio contact is trivial, such as simply sleeping through the schedule, the Polar Shelf will put in a bill for the air time spent on re-establishing contact, for an important function of the twice-daily radio contact is to track the status of each group of scientists working in the field throughout Canada’s Arctic. It is to everyone’s advantage to pass along position information and plans for camp moves to the officials in Resolute.

With their radio not functioning, the team was completely cut off from the outside world. As the group sat around discussing the consequences, they guessed it must be a radio blackout caused by solar activity—a relatively common occurrence. What worried Beattie was that, in their last radio contact with Resolute, they had indicated they were on their way to a predetermined camp location, 25 miles (40 km) south at Erebus Bay. Loss of contact with Resolute meant there was a possibility that a plane would be sent out within the next day or two to Erebus Bay. There was some urgency, therefore, to get to that location before the plane. Three thoroughly exhausting, long days of surveying and backpacking followed before radio contact was at last resumed; for those days, they felt like they were the only people on earth. The absolute isolation imposed by the radio blackout was a sobering experience, one they were not anxious to repeat.

As they approached Rivière de la Roquette across a dismally flat landscape, two small objects caught their attention. The first was a small grey lump in their path, which soon revealed itself to be a young Arctic hare, or leveret. Born fully haired, with their eyes wide open, hares are able to run just minutes after birth. This tiny, gentle animal stood out in stark contrast to the forbidding landscape. It was rigid with fright, its heart pounding. The four watched it for a time, took some photographs, then continued on. The second object turned out to be what was almost certainly an Inuit artefact, constructed from material collected in the nineteenth century from a Franklin site. It resembled a primitive fishing rod made of two pieces of wood and twine; the wood held together in part by a brass nail. It was a good example of the use made by the Inuit of abandoned European artefacts.

Surveying the coast had largely meant walking along beach ridges of limestone shingle and sloshing through shallow sheets of water draining off the island. Now, as they held up their hands to shade themselves against the sun, the team could see the other side of Rivière de la Roquette, .125 mile (.5 km) to the southwest; beyond that point the land was too flat to pick out any landmarks. The river itself posed a considerable obstacle, and there was discussion as to whether they should attempt to walk round it, out on the ice of Erebus Bay. However, earlier that day they had been able to see the effect of the river’s flow on the ice in the bay. The volume of water had pushed it far offshore, and the ice that could be seen through binoculars did not look inviting. Finally, all agreed that to walk out on that rotten ice would be too dangerous; the river would have to be waded.

Beattie recalled the vivid description of Schwatka’s group when they had stood on the same spot 103 years before: at that time the river was considered impassable down near its mouth, and the group had to hike inland a number of miles to where the river narrowed and they could cross in icy-cold, waist-deep water. Beattie wondered how he and his crew, far less rugged and experienced than Schwatka’s men, would fare in gaining the far bank. Carlson and Tungilik had hip waders, which they untied from their backpacks and put on. Kowal donned pack boots that reached to mid-calf and began slowly wading out into the shallow edge of the river, searching carefully for submerged banks of gravel that would allow him to keep the water from rising above the boot tops. Tungilik struck out along the same route. Carlson and Beattie unpacked and began inflating a two-man rubber boat that they had carried (along with a set of oars) since their survey began. They planned to use it to float their supplies across the river, but Beattie also hoped to find a way to keep his feet dry. As he had only pack boots himself, it seemed reasonable to have Carlson, in his hip waders, pull him across the river in the boat. Kowal was too far away for the others to see if he was having success in keeping dry, and the wind and distance were too great to shout to him.

Carlson and Beattie had problems inflating the boat with the rubber foot pump, and when the craft was half-inflated, the pump ceased working altogether. Despite having a rather floppy, unmanageable water craft at his disposal, Beattie loaded his pack and climbed in. He quickly found himself floundering—before finally tumbling over on his back with his legs sticking up in the air. After a good laugh, he righted himself and, soaked, climbed out of the boat. He and Carlson started wading slowly across after the others, the empty and limp boat bobbing and swivelling downstream from a rope attached to Carlson’s pack. The water turned out to be very shallow almost the whole distance across, though within 160 feet (50 metres) of the other side it increased to knee depth.

Resting by a rock near the river bank the four looked off to the west across a forbidding 6 miles (10 km) of mud flats. Their next stop would be the food cache that had been dropped from the plane on the first day of the season. They needed to replenish their supplies: over the past two days they had virtually run out of food and fuel, and they were looking forward to the supplies they had packed in the distant cache. So, thinking as much about their empty stomachs as the obviously difficult walk before them, they struck out onto the grey-brown featureless mud flats.

The clay-like mud had melted down 4 inches (10 cm) or more and was soft and pasty. Each footstep squeezed the mud out like toothpaste, and the friction and suction made extracting their feet a struggle. At first they sank in only up to their boot tops, but as they pushed a few more miles out onto the flats, there was more water in the mud. Now their feet sank down to the permafrost. The grip of the mud, sometimes ankle-deep but at other times more than knee-deep, was so strong that they often pulled their feet right out of their boots.

At times they would encounter an island of vegetation where the footing was good, and at each of these spots they would take a short rest before plunging into the mud again. In one of these “islands,” the intact skeleton of a bearded seal was found. Virtually undisturbed by animals, it looked almost surreal against the backdrop of the mudflats.

Halfway across they began to see the slightly raised beach ridge that marked the location where they had dropped their cache, and two hours later, when they finally started up the nearly imperceptible slope of the western extent of the flats, they were within only a few miles of their next camp. When at last they reached firm ground, they threw their packs down and sat to rest their legs.

It had taken more than four hours to cross the flats. Although the cold wind blew persistently off the ice at Erebus Bay, the day was sunny and warm, nearly 50˚F (10˚C), and before long all were lying on their backs, soaking in the sun, thankful that they did not have to return by the same route. Twenty minutes passed with hardly a word said before one of them, Carlson, finally sat up and busied himself with his pack. Their bodies now rested, stomachs began to growl; the next goal was the cache.

Walking to the west they dropped quickly down into another flat area, but this one was only two-thirds of a mile across and had good footing. Several pairs of whistling swans, which had constructed their large nests here, could be seen nearby, and the four men paused to observe the large and majestic birds before continuing on their long walk. Then, in the middle of the flats, Tungilik stopped dead and, pointing at the ground, asked Kowal, “What’s this bone?” Kowal was shocked to see a right human tibia lying on the surface of the flats. He called to Beattie and Carlson, who had been following. As the others hurried towards them, Kowal decided to have some fun. He quickly covered the bone with a piece of driftwood. When Beattie and Carlson finally arrived, both panting under the weight of their packs, Kowal said, “Look at this!” Beattie looked down at the wood and said, “You made me hurry up for this?” Then, turning the wood over with his foot, a broad smile crossed his face. All thoughts of reaching the food cache quickly vanished as the team searched the location for other bones. Five more were found nearby, as were two weathered pieces of wood planking, one of which had remnants of green paint, a brass screw and badly rusted iron nail shafts. Because the six bones were from different parts of a skeleton, it seemed likely that they were from one person. However, since none of the bones was from the skull, it was not possible to tell whether the person was a European or Inuk, though the bones were close enough to the location of the lifeboat first found by M’Clintock that they were most likely those of one of Franklin’s men. The wood planking supported this interpretation.

The bones were photographed, described, then collected, and the location marked on the team’s maps. Elated with their discovery and feeling renewed confidence that this area of the boat would yield new and important information, they continued on at an increased pace. When they saw the bright pink bundles of supplies in the distance, they broke into a jog and, if the packs had allowed, would probably have raced to their cache. Reaching the bundles almost simultaneously, they unslung their packs, rummaged quickly to locate their knives and within seconds were all slashing away at a claimed bundle. Each man searched for his favourite food: Kowal was looking for boxes of chocolate-covered macaroon candy bars; Tungilik, cans of roast beef; Beattie, tins of herring; and Carlson, canned tuna. With hardly a word to each other they dug into their food, sitting on the sandy beach ridge among the debris of their haphazard and comically frenzied search. The sounds of chewing, the crackle of plastic wrappers and the scraping of cans were interrupted by Kowal: “Can you believe us?” he said, looking up from a near-empty package, a chocolate macaroon poised in his right hand. “And we’re not even starving. Those poor guys must have really suffered.”

On 12 July the surveyors headed out from their newly established base camp. They found nothing more in the area where they had discovered the six bones, just two-thirds of a mile from their camp, but 2 miles (3 km) to the west of the camp they discovered a 100- by 130-foot (30- by 40-metre) area littered with wood fragments. As they closely searched the site, larger pieces of wood were also found. Schwatka’s description of the coastline and the small islands a few hundred feet out in Erebus Bay left the men with little doubt that they had reached the boat place where the large lifeboat from the Franklin expedition, filled with relics, was first discovered by M’Clintock and Hobson in 1859 and later visited by Schwatka in 1879. But the sight that had filled M’Clintock and the others with awe so many years before had vanished: the skeletons that once stood guard over their final resting place were nowhere to be seen. An exhaustive search of the site was conducted, and slowly, out of the gravel, came bits and pieces that graphically demonstrated to them the heavy toll of lives once claimed by the desolation of King William Island.

In the immediate vicinity, they eventually located many artefacts, including a barrel stave, a wood paddle handle, boot parts and a cherrywood pipe bowl and stem similar to those found by M’Clintock at the same site. More important, however, was the discovery of human skeletal remains. From the boat place and scattered along the coast to the north, they found bones from the shoulder (scapulas) and leg (femurs, tibias). Several of the bones showed scarring due to scurvy—similar to the markings discovered on the bones found a year earlier near Booth Point. (In total, evidence of scurvy would be found in the bones of three individuals collected in 1982.) The team worked long and hard, each of the four men combing the ground for any relic or human bone. Dusk soon surrounded them, but no nightfall follows dusk during the summer at such high latitudes. It was under the midnight sun that Tungilik made the survey’s most important find.

Cherrywood pipe.

While systematically searching the boat place, Tungilik caught sight of a small ivory-white object projecting slightly from a mat of vegetation. Picking at the object with his finger, out popped a human talus (ankle bone). With his trowel, Carlson scraped the delicate, dark green vegetation aside, revealing a series of bones immediately recognizable as a virtually complete human foot. Continuing his excavation, which lasted into the early morning hours of 13 July, Carlson found that most of the thirteen bones from the left foot were articulated, or still in place, meaning that the foot had come to rest at this spot and had not been disturbed since 1848. The remaining skeletal remains varied from a calcaneus, or heel bone (measuring 3 inches/8 cm in length), to a tiny sesamoid bone (no bigger than .12 inches/3 mm across). Also found was part of the right foot from the same person, which supported the interpretation that a whole body once rested on the surface at this spot.

M’Clintock had argued that, as the lifeboat was found pointing directly at the next northerly point of land, it was being pulled back towards the deserted ships, possibly for more supplies:

I was astonished to find that the sledge (on which the boat was mounted) was directed to the N.E…. A little reflection led me to satisfy my own mind at least that this boat was returning to the ships. In no other way can I account for two men having been left in her, than by supposing the party were unable to drag the boat further, and that these two men, not being able to keep pace with their shipmates, were therefore left by them supplied with such provisions as could be spared, to last them until the return of the others with fresh stock.

The 1982 discoveries at the boat place supported this interpretation: the human skeletal remains were found scattered in the immediate vicinity of the lifeboat, and in the direction of the ships for a distance of two-thirds of a mile. It appears that those pulling the lifeboat could go no further and had abandoned their burden and the two sickest men. They continued on, but some had nevertheless died soon after.

In all, the remains of between six and fourteen individuals were located in the area of the boat place. In determining the minimum number of individuals from the collection of bones, Beattie first looked to see how many of the bones were duplicated. Then he examined their anatomy, such as size and muscle attachment markings, comparing bones from the left and right sides of the body to see if they were from one or more individuals.

Beattie was sure that the bones had been missed by Schwatka. From his journal, it is obvious that Schwatka was reasonably thorough in his collection of bones. He had discovered the skull and long bones of at least four individuals and buried these at the site. As in the previous searches along the coast that summer, Beattie and his crew were not able to find this grave. Of the bones discovered by the scientists in 1982, no skull bones were found.

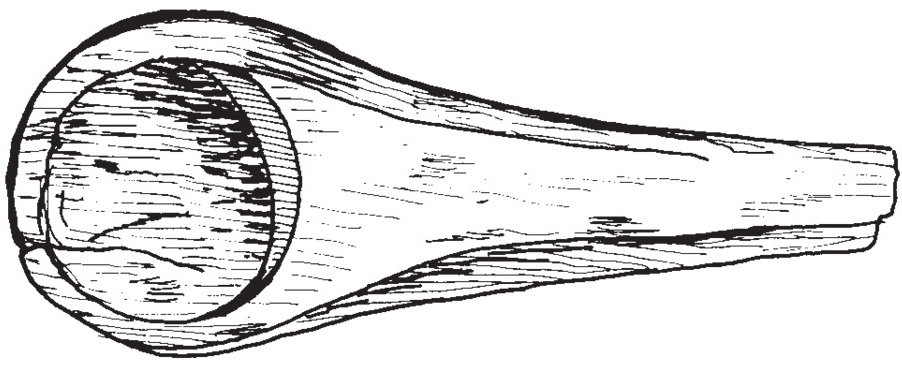

Strangely, the most touching discovery made at the boat place was not a bone but an artefact, found by Kowal. Surveying a beach ridge further inland on 13 July, he saw, lying among a cluster of lemming holes, a dark brown object that, on closer inspection, turned out to be the complete sole of a boot. Picking it up he could see that three large screws had been driven through the sole from the inside out, and that the screw ends on the sole bottom had been sheared off. Kowal carried the artefact back to camp, where the others, who had been cataloguing the collection, examined it. It was obvious that the screws were makeshift cleats that would have given the wearer a grip on ice and snow—a grip absolutely necessary when hauling a sledge over ice.

Boot sole found at the “boat place,” showing screw “cleats.”

It was this object, more than even the bleached bones of the sailors, which brought home to the four searchers the discomfort, agony and despair that the Franklin crews must have endured at this final stage of the disaster. For the research team, the piece of boot symbolized the final trek of the men of the Erebus and Terror. The imagination can play tricks in such situations. And while sitting alone during the dusk-shrouded early hours of 14 July, with brisk winds blowing in off Victoria Strait, Beattie felt that Franklin’s men did indeed still watch over the place. It was as if the dead crewmen might yet rise up for one last desperate struggle to ascend the Back River to safety.

Later, Beattie, Carlson, Kowal and Tungilik surveyed 3 miles (5 km) further to near Little Point. To the west of this location was a long inlet filled with rotten ice, which effectively formed a barrier to any further survey that season. And so, packing their precious cargo of bones and artefacts, the team readied to leave the island. With the King William Island surveys at an end, Beattie was already wondering what new insights into the Franklin disaster his small collection of bones would provide.